对话安藤忠雄——建筑,一场永无止境的挑战

FA:安藤忠雄先生,您好!首先祝贺您的双个展在上海复星艺术中心及顺德和美术馆顺利开幕,全球疫情尚未结束,大量艺术活动和艺术机构还处于停摆之际,在中国举办两个大规模个展,对您而言有何不同于往常的意义?

安藤:我已经79岁了,目前还没有停止工作的打算。不管你的年龄多大,做一个未成熟的青苹果总比做一个成熟的红苹果好。不成熟就是要年轻,要天真,要有活力,要去不断尝试可能以失败告终的冒险。引用一首我最喜欢的诗人塞缪尔·厄尔曼(Samuel Ullman)的诗《青春》中的句子:“岁月悠悠,衰微只及肌肤; 热忱抛却,颓废必致灵魂。”

这两个展览是我近半个世纪的职业生涯的记录,包括正在进行的项目和尚未完成的工程,以及各种各样的创意挑战,囊括了我从职业拳击手到自学成才的建筑师的成长历程。自从1969年我创立了自己的第一个工作室以来,我不断在尝试用建筑来颠覆原有的审美观念,创造一个新的设计世界。作为一个以全世界为工地的建筑师,我总是持续努力创作新作。

我们生活的时代,世界正在以惊人的速度发生巨变,新冠肺炎的全球大流行打乱了我们的生活方式。尽管如此,我依然相信为人类提供建筑和艺术是至关重要的。文化滋养我们的身心,让我们的生活充满活力和激情,我认为这种力量总有可能以超乎我们想象的方式为人类社会带来新的价值。

FA:在复星艺术中心现场,我们看到您大量的项目模型,这些项目遍及世界各地,在全球化所带来的同质化语境下,针对不同城市的风貌特征和文化肌理与新建筑的关系,您都试图给出回应,从1988年中之岛都市巨蛋古典平面中置入的大卵,到曼哈顿顶层公寓突出立面的大玻璃盒子,这些看上去很疯狂的方案是对现代都市建筑的一种反叛吗?

安藤:建筑是经济社会的产物之一。一项工程是由客户与建筑团队共同参与实现整体结构的协作工作。这一切都是在满足各种条件的同时完成的,包括成本、法律法规、工程期限等等。在这个高度复杂的创造系统中,你几乎找不到能够自由表达的空隙,或者去追求你的设计“梦想”。然而,对我来说,建筑的本质恰恰就存在于其中,在深陷冲突中去突破限制。

我在工作中会时常偏离这套社会框架,转向追求理想的、纯粹的、单一的建筑形式。这方面最突出的例子是1989年首次宣布的中之岛都市巨蛋工程,我在还没有得到官方委托的情况下,就开始构思这个位于大阪市中心的中之岛的文化综合体工程。这项工程的中心就是嵌套在历史悠久的中之岛公共大厅内的,被称为都市巨蛋的改造项目。我的想法是在大厅结构的内部插入一个巨蛋,同时保持建筑原有结构的完整性。从这个概念出发,我就一直在研究一种将大阪的记忆嵌入中之岛的建筑中的方法。至于这个概念如何实现,我尚且没有明确的方案。因此,我依旧致力于创作图纸和模型,希望能更大胆、更深刻地向世界传达这种新型建筑的理念。

这种类型的建筑首先应该通过在地语境的对话来回应地方性,即本地的文化和历史景观。这种观念并不总是与环境达成和谐一致的表达,有时候,恰恰是完全对立冲突的,突兀大胆的干预产生对城市的全新诠释,在20世纪下半叶的巴黎建筑中有很好的先例,从蓬皮杜中心到卢浮宫新馆,也许最重要的是它们对现有的城市主义机制所作的批判宣言,让建筑成为这种不妥协精神的代言。这种批判越纯粹,建筑就会越激进,就越会挑战现有的社会秩序。当众多能够克服这些冲突的建筑形成网络,环境被注入鲜活力。

FA:今天全球城市的发展都将面临灵活性及可持续性这两大问题,在您看来哪些新技术新材料的出现会给建筑实践带来根本的转变以应对上述问题?后疫情时代,建筑又将如何回应这个越来越复杂分化和冲突不断的社会?

安藤:都市环境的问题归根结底是现代社会人造景观与自然资源的不平衡造成的。如果我们从建筑环境的角度来看这个问题,解决方案可以抵达两个极端:一个是“低技术”世界,明显地减少能源消耗; 另一个是“高科技”世界,通过使用可再生能源,让技术在紧凑、人工化的生活模式中发挥效应。

无论我们朝哪个方向走,现代社会的城市活动都要受到限制。世界必须改变,最重要的是我们要有问题意识,要改变价值观。为了一个可持续的未来而改变城市架构不能仅仅通过政治家、开发商和建筑师的力量来实现,我们需要借力地球上的每一个人。自然不是我们的权利,而是我们被赋予的特权。为了环境的发展,人类也必须进化。

FA:在半个多世纪的建筑师生涯中,您形容自己是屡败屡战,竞标与拳击一样,都必须抱有高昂的斗志,以及击败对手的强烈欲望。在复星艺术中心展出的百余件建筑模型中,哪一个竞标项目对您而言有着非同寻常的意义?

安藤:在一场拳击比赛中,等待铃响的那一刻最令人兴奋,也最让人神经崩溃,每一个新的建筑项目也要求你有同样的精神状态。在拳击比赛中,你必须冒险将自己置于危险之中,逼迫自己拿出最佳的技术,最终赢得比赛。建筑不仅仅是造一幢房子,重要的是还要创造出一些东西。这就需要有冒险的勇气,敢于向未知多迈一步,这是至关重要的。一名拳击手苦练多年,就是为了拳击场上几分钟就结束的回合,这就是一场战斗,简单而原始的战斗。然而建筑是一场远超过三分钟的漫长的比赛,但你必须像拳击手一样保持紧张感。有时候,建筑師也会被成名的欲望诱惑而失去自律,忘记自己事业起步时的孤独无助。拳击是一种严格自律和孤独的运动,你在把身心推向绝对极限的过程中变得强壮。建筑也是如此。每个工程都有严格的计划和预算,没有多少任你自由发挥的余地。你必须想清楚真正必要的是什么,你需要建造的是什么。

FA:在中国的项目中,请您先以顺德和美术馆为例,谈谈您对岭南建筑、文化的理解,以及您又是如何将这些传统融入美术馆的创意与设计中的?设计的原点是什么?

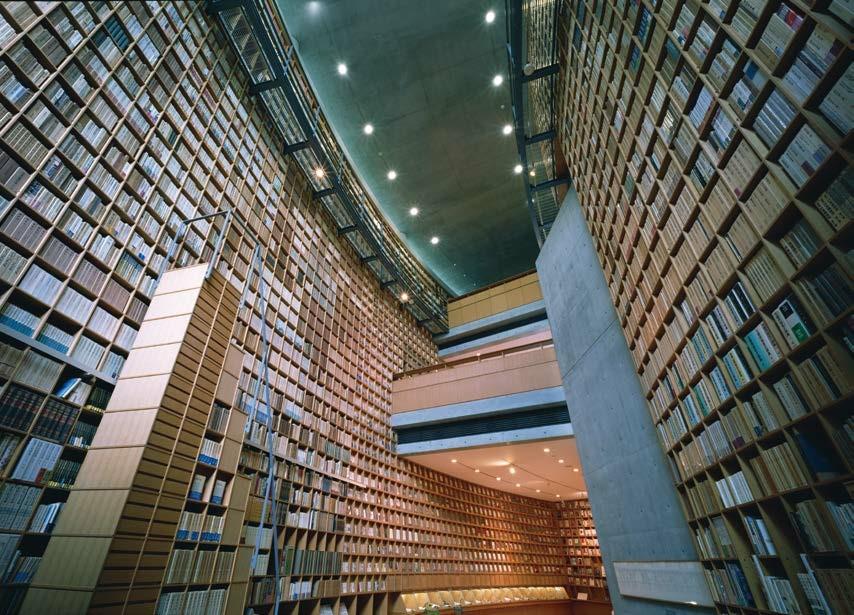

安藤:我首先想到的是,这座建筑要表现一大片水中溅起的一道涟漪,它的核心位于“跌落的鹅卵石”的隐喻上,随着溅起波纹的直径逐渐增大,水的能量反射到周围环境中。这个设想造就了美术馆的主体是四个垂直堆积的圆形体,它们以固定的增量扩散增长,重叠圆立体的排列创造出拥有清晰的同轴的独立空间,充满动力和变化,呼应着城市自身的能量。核心筒将整个概念连接在一起,成为美术馆中最具象征意义的重要空间。

从项目一开始,客户就决定以“和”字命名美术馆,表达他们希望通过艺术和文化,创造和谐共生,和睦相处的愿望。我完全接受这个想法,在设计过程中加入了许多表达这个意愿的设计。

美术馆的入口,包含着自然和人工的强烈对比,给参观者意想不到的“惊喜”。围绕入口水景的是被绿植覆盖的双层混凝土墙,墙壁和绿植蜿蜒起伏,墙体与植物间可透可视,创造出空间的深度,这个设计的灵感来自中国传统园林。水景的重要性不仅在于映照建筑物,它也协调了建筑与周围景观及城市环境的和谐。

岭南文化有其独特的力量,也大大启发了美术馆的设计。而岭南传统深受中原文化思想的影响,和美术馆的设计目标之一就是传承中华文化的力量。然而,我并不想使用传统的文化标示来表达这个主题,而是希望融入文化背后精神性的精髓。岭南地区的古代南越王国文化中,圆是和谐(阴阳)和吉祥的象征,这可以在许多历史的建筑和艺术品中看得到。美术馆的圆形代表了根植于当地方言的几何学。

FA:和美术馆筹备5年,建造花了3年,和美术馆的清水混凝土双螺旋中庭楼梯结构在施工中难度是非常大的,听说最后还是派了与您长期合作的青木先生过来,工程才得以顺利进行,在项目结束后您给当地的施工团队写了一封信,能否透露一些信中的内容?

安藤:和美术馆核心筒的双螺旋混凝土楼梯是这座建筑的灵魂,但建造起来确实很难。围绕楼梯的混凝土墙壁支撑着螺旋楼梯,是整个美术馆的核心;它的设计包含一种象征性的螺旋体验,是建筑结构的核心。

建筑无论大小,总会有各种问题,所以就是在不断克服问题中,一座牢固的建筑才得以诞生。我们在施工现场与青木先生无休止地对话,当地建筑师和施工团队的不懈奉献,确保了建筑高质量地完成。在任何工程中,当地施工队都是直接解决施工现场问题的首选,我非常感谢当地施工团队和当地建筑师的努力。

FA:在传统的建筑营造中,建筑师与工匠们是同在现场的合作关系,而现代建筑学科的发展令建筑学过于细分,建筑师与营造开始脱离,我们该如何看待手工建造和传统工艺的价值,也请您顺便谈一谈您与不同国家地区的工匠们合作中的趣事,以及他们之间的差异。

安藤:起初在中国做项目时,我试着遵循在日本时的设计和施工。但中国有不同的价值观和文化,在日本能够实现的想法也不能在中国精准复制,这倒不是因为技术能力,而是文化差异。通过我在中国过去几十年的建筑生涯,我认识到了中国巨大的能量和活力,最近几个项目的成功实施证明了中国建筑技术水平的巨大飞跃。

我工作的每个国家都有各自的建筑方法、材料类型和文化差异。然而,所有国际项目的共同点是有一个充满激情的甲方和施工团队。建筑是一种团队工作,需要许多有才华和勤奋的人之间的信任和协作才能实现。

FA:在所有的已建成项目中,有没有出现过您所不能接受的失误?甚至是失败?毕竟混凝土浇筑只有一次机会,在拆开模具的瞬间,您还会紧张吗?您为何如此钟爱混凝土这种语言?随着新技术新材料的出现,例如3D打印的普遍使用,您是否会考虑在未来的项目中做一些新的建筑实验?

安藤:混凝土是当代建筑的材料象征,全球任何地方都有,但我的热情一直是用这种随处可见的材料创造无处可寻的空间。

混凝土的魅力在于它能够根据地域和使用者的不同而变化,每次使用,所表达的深度都会完全改变。勒·柯布西耶用起混凝土来就像是黏土,做雕塑一样发挥混凝土的可塑性。路易斯·康把混凝土用得像钢一样坚硬。同样的材料,两种完全不同的效果。同样,在我的职业生涯中,我也一直在寻找我自己的使用混凝土的方式,就像做日本屏风的和纸一样。

FA:传统的中国南方建筑与日本建筑对于空间的理解是有相通之处的,西方建筑以物为先,空间总体是围合的,东方则以关系为先,空间多是半开放的;日本建筑的特点概括而言便是两块木板的关系,重在轻盈,其中的橼侧设计更是一大特点,通过它可以将建筑内外空间灵活地隔断或连接。 从空间关系处理来看,您的建筑似乎更接近欧洲建筑传统,更为注重光影的游戏、空间的戏剧性张力以及几何体的运用?

安藤:对我来说,东西方建筑最大的差异就在于光的运用,以及实与空的观念。光是一面镜子,反映一个地方的文化。西方建筑史的观念一直是在石料上开孔,让光穿透出来,照亮黑暗。像罗马的万神殿,光线随着太阳运动的轨迹不断变化,从圆孔中流淌出来;还有塞南克修道院,纯粹且朴素的光线传递终极的灵性。日本是一个岛国,温和的气候使得区分内外的“墙体”显得不那么重要,传统建筑中的元素,例如日本屏风,就如木质或是纸质的“伞”呵护着屋檐下生活的我们。光线在传统的日本建筑中不是直射的太陽光,而是阴影造就的斑驳柔和的光。在光线的认知和使用上,我受到的影响来自东方和西方。

FA:现代主义建筑强调形式与功能的一体化,然而我们仍处于片面追求地标性建筑的时代,过分张扬的形式必然会导致功能的缺失,您又是如何做取舍的?一座好的建筑应该拥有哪些品质?今天重新再看柯布西耶、密斯·范·德·罗、路易斯·康、赖特这些现代主义大师所创造的建筑原型,我们还有推陈出新的可能吗?或者说,我们还能把失去的那些思想精髓重新找回来吗?

安藤:建筑与其他艺术最大的区别就在于它的功能性。我所说的功能,并不是指一座建筑使用起来的难易性,而是人之于建筑空间是否存在恰当的比例。不管是一座已经完工的建筑,还是一个尚未实现的工程,甚至是一个信马由缰想象出来的建筑方案,如果没有将人的因素考虑进去,建筑就不存在。建筑生成的体系与对这一体系的解析,都与建筑本身息息相关。

然而,艺术与建筑的界限是什么呢?艺术家有胆识勇往直前,建筑师也必须敢于突破,挑战未知世界的恐惧是人类的共情,只有艺术与建筑的结合方可推陈出新,超越建筑与艺术的界限,捕捉新的人类表达自由的形式。

FA:您曾经说过到75岁以后也许会回到最初的状态,做一些有趣的小项目。您的住吉的长屋和神户4×4的住宅都有着丰富的建筑表情,倔强生动又充满张力,这些特质在大体量项目中就很难再看到了。您今天还会坚持承接这类小的项目委托吗?

安藤:是的,我为陶瓷艺术家黑田泰藏设计了一个只有17平方米的非常小的画廊,黑田太郎先生不幸在本月去世了。我设计了一个浅水池,黑田先生的陶瓷作品能够映射其中。

FA:您设计了大量的住宅,我很好奇您自己又是住在怎样的房子里?我的建筑师朋友们很想知道,您在生活中除了锻炼还有什么喜好吗?我倒是觉得您可能是位禁欲主义者。

安藤:我住在离办公室五分钟路程的一座高楼里,我想我不会喜欢住在我自己设计的房子里,混凝土夏天太热,冬天太冷!

我的爱好之一是种树,在我家乡大阪周围植树搞绿化。这个爱好始于1995年阪神地震后,我开始在来年加入兵库绿化网络。我常听人说在地震中,大树可以保护房屋免于坍塌,神户地震发生后,我曾立即去那边实地考察,第一次看到灾后的头一个春天里盛开着白色木兰花,似乎在安慰那些在灾难中失去亲人的人。在当地政府制定灾后造房的建设项目时,我产生了一个想法,在计划建造的12万5000座住房中,每个单元种两棵树。通过在建筑物之间植树,我希望绿化能够创造新的社区,修复震后的城市景观。非常感谢日本各地居民和城镇的捐款,我们才超额完成了最初的目标,种下30多万棵树。从那以后,植树成为我一直坚持的事业,我还做了东京湾的海洋森林和在直岛种植樱花树。

FA:日本六七十年代涌现出了大批文化先锋人物并影响了世界,请您给我们讲讲您对那个时期的一些深刻印象以及您与艺术家朋友交往的故事。第一次在白发一雄的行为现场所感受到的冲击一定很强烈吧!前卫艺术对于您在建筑实践中最直接的触动和帮助又是什么?

安藤:围绕在1954年成立的“具体派”(gutai)艺术运动周遭的是一大批不同类型的艺术家,例如向井修二画象形符号,松谷武判用铅笔把画布填满了黑色。参与到具体派中的每个人似乎都有些古怪的个性,包括创始成员吉原治良和岛本昭三,以及田中敦子、元永定正等人。他们并不像艺术家,他们对自己的生活方式不在乎,只在乎如何用独特的方式表达自己。对他们来说,艺术是一种突破束缚自由思考的现有社会习俗和制度,他们从一开始就用自己的眼睛审视周边。

除了具体派,我还和一些艺术家和设计师有过联系,比如草间弥生、三宅一生等等。他们在各自领域探索未知的挑战精神激励了我,我与他们相处甚欢,因为我们都是在同一条路上,最大限度地挑战创造的可能性。我相信,艺术的“财富”就是它能够被多样化解读的“自由”,当自由驰骋于风景之间,隐藏于人们的日常生活中,这样的社会才是真正的繁荣社会。

FA:理查德·朗(Richard Long)是我很喜欢的一位艺术家,他在大地间的行走和留下的作品让我想到中国的道家思想,一种身心和谐的生命超越精神,他的作品也最终成为了自然,就像您在直岛所建造的那些美丽而静寂的掩体,您还记得理查德·朗在直岛留下的作品吗?

安藤:当然记得,这里还有一个有趣的故事呢。其实这是福武总一郎先生的愿望,他想要把理查德·朗(Richard Long)的作品放入我在直岛设计的倍乐生之家( Benesse House )美术馆里。福武先生有种很强的直觉,他相信如果他把颜料和画笔放在美术馆的空墙旁,理查德·朗可能就会拿起笔来作画。果不其然,事情就是按照他的设想发生了,现在美术馆墙上有两件理查德·朗的画,就是他直接画在墙上的。

FA:和美术馆的《超越:安藤忠雄的艺术人生》的第一篇章《超越藝术》展出了包括 毕加索(Pablo Picasso)、埃尔斯沃斯·凯利(Ellsworth Kelly)、亚历山大·考尔德(Alexander Calder)、理查德·朗(Richard Long) 、安尼施·卡普尔(Anish Kapoor)、达米恩·赫斯特(Damien Hirst)、白发一雄、吉原治良、李禹焕、杉本博司十位艺术家的重要代表作,您为这十件作品各自设计了不同的空间。邵舒馆长告诉我为了配合您这个展览,团队根据您的《都市彷徨》所提及的艺术线索专门收藏了其中八件作品,这些都几乎是天价之作!中国有句话,千金易得,知音难求,你有着令所有建筑师都会嫉妒的甲方,这些友谊也像您的建筑一样成为了传奇,您到底是如何做到的?

安藤:我对艺术的认知是建立在我年轻时与当代艺术的一次次生动接触的记忆上的。杰克逊·波洛克(Jackson Pollock)的行动绘画, 20世纪60年代聪明的波普艺术,以及日本第一个具有全球影响力的前卫艺术运动,具体派艺术协会(Gutai art Association)。具体派艺术家对我的影响非常重要,因为我们都住在日本关西地区,常常有联系。

保持与他人的关系对于一名建筑师是至关重要的,当你和一群志同道合者充满激情地一起工作时,你们之间就会建立起来相互理解和尊重的联系。我从不搞关系,我在不断地向周围的人学习。

FA:直島项目历时30年,如同自然界的生物般生长交织,完美地演绎了您对于建筑的乌托邦想象。直岛就像是您的大道场,在艺术的加持下,颓败荒废的小岛拥有了近乎永恒的生命。您和福武总一郎、李禹焕先生在第13届上海双年展共同带来的讲座——“‘渗透’—‘海之复权’与乡土重生”,为当下中国的乡村建设与乡村复兴运动带来了特别的样本,“直岛模式”也已被福武先生带到中国山东桃花岛,到底是什么样的信念让福武先生和您坚持了30年?

安藤:直岛是在倍乐生控股公司(Benesse Holdings,Inc.)的福武总一郎(Soichiro Fukutake)总裁的热情支持下开启的项目。

要使建筑与自然达到完全统一,需要时间和耐心。设计和建造并不是挑战,真正的挑战在于工程竣工后的维护和对它的热爱。我相信建筑师有责任培养他们的作品,让它们在时间的推移中渐渐成熟起来。在过去的30年里,我在直岛全身心地投入,建造了七个博物馆。艺术、自然和人的碰撞激荡人心,产生无数可能性,直岛上嵌入地下的几何体建筑物诱发着游客的想象力,搭建起人与艺术及环境的对话。

我在直岛的大部分建筑都遮掩在大自然里,每栋建筑的外观并不暴露建筑内部的设计,参观者可以不去理会建筑的外形,而将注意力集中在身处艺术作品和景观之中的个人感受及对空间的体验。许多艺术作品放置在岛上的公共空间,濑户内海的大自然成为给每一位艺术家搭建的舞台。艺术家也常常以周围环境为灵感,创作在地作品。在直岛的所有项目中,我一直坚持的理念就是艺术、建筑和自然的结合,共同打造复兴的力量。

FA:城市更新与乡村复兴已成为当下及未来中国城镇规划的重要课题,这也给更多的年轻建筑师提供了舞台。 面对萧瑟萎靡又空心化的乡镇,日本有很多经验值得我们学习和借鉴。建造之外,在地性、可循环、持续性甚至是产业结构和项目运营似乎都是建筑师需要面对的问题,在您看来,今天的建筑师身份是否更为复杂也更充满了挑战?

安藤:我们正处在一个文明的转折点上,经济增长时代正在进入下滑和衰退期。在日本和中国等亚洲国家,普遍存在着建筑翻新维修与拆迁重建的问题,维修的范围包含从文化遗产的恢复和保护,到普通建筑的改造和再利用。尽管维修建筑的类型看起来完全不同,但它们都是以利用现有建筑的卓越理念为前提,而不是一味地拆除。

对建筑的维修实质上是对居住地的共同历史记忆的保护。考察一下巴黎或纽约这样的大都市,我们可以发现,城市历史的聚合孕育了城市文化。历史是通过有形的物件保留下来的,而不是用信息或虚拟现实塑造出来的某种依附在城市肌理之上的临时性的所谓文化“土壤”来传递的。当然,建筑物在变老,对维修和保护它们所需的技术力量和经济实力的要求就更高;有时,保护建筑物的历史和记忆的努力可能正是如何对其有效地再利用的最大障碍。然而,我相信改造的目的就是为了传承历史,它的众多好处远远超过为它过度消耗劳动力和创造力所带来的挑战。传统与现代的频繁对话将唤起从过去到现在再到未来的时间交织的城市肌理。时间和空间相互交融,以确保我们的城市能够为子孙后代继续维持生计。

FA:《FA财富堂》杂志有一个建筑设计板块,专门用来介绍中国青年建筑师的乡村建设项目,并为此设立了一个“FA青年建筑师奖”,以鼓励更多的年轻人特别是主流建筑流派之外的建筑师群体参与到乡村建设中。可否请您为这个活动送上您的寄语,以激励这些青年人的斗志。

安藤:我会告诉我年轻的自己,永远去追求你认为具有挑战性的事业,永远不要放弃你的梦想。我相信,无论你是否选择做一名建筑师,二十多岁都是影响你今后生活的关键年龄。如果你能在自己敏感的二十几岁保持警觉,这将决定你能否在四五十岁时过上你想要的生活。

在这一时期,年轻人寻找自己的理想,创造自己的世界观,可以说这是塑造自我的年纪。在我二十几岁的时候,我遇到了一些人和事,这些人和事最终塑造了我的本质,造就了今天的我。二十几岁是一个与他人建立密切关系的时期,在这时候的经历直接影响了我后来的工作。我年轻的时候有很多朋友在京都大学学建筑,通过他们,我了解了哲学家和辻哲郎和西田几多郎,他们在当时的学生中有很高声望。命运真是件有趣的事,1980年,我在姬路创建了和辻哲郎纪念馆,并有幸设计了石川县西田几多郎哲学博物馆。在我年轻的时候开阔了我的视野的各种经历直到今天依旧对我有影响,始终如此。

FA:如果您当年没有看到柯布西耶的作品全集,您还有可能从事建筑职业吗?

安藤:我不确定未来会发生什么,我尽量不去想“如果”的情景,就是继续不停地朝着未来走吧。

FA:最后,我想给您讲一个发生在我身边的故事。第一届“FA青年建筑师奖”有一位获奖者,来自中国湖南乡村的年轻人,他没学过建筑,也没上过大学,他的理想就是可以留在北京,并且拥有自己的房子。直到有一天,在北京潘家园的旧书摊上他看到了一本书,这本书的主人公令他钦佩不已,他随即决定要重新启动自己的人生。为此他卖掉了自己在北京的房子,并切断了与外界的全部联系,去到一所大学的建筑系做了几年的旁听生。在获奖之后,他被大家戏称为“自学成才的野生建筑师”,这位年轻人叫王求安,他看到的那本书,是您的《屡败屡战》。

非常感谢您接受我的采访,祝您健康长寿,平安快乐!也期待上海的安藤忠雄画廊尽快与大家见面!

FA: Dear Mr. Tadao Ando, how are you? First of all, allow me to congratulate you on the successful opening of your two solo exhibitions in China -Shanghai Fosun Art Center and Shunde He Art Museum. At a time when the global pedantic is still ruling the world and a large number of art events and art institutions are still closed , holding two large-scale solo exhibitions in China must mean something specific to you than usual.

Tadao Ando: I am seventy-nine years old and do not plan to stop working anytime soon. No matter your age, it is better to be an unripe green apple than a mature red apple. To be unripe is to be youthful, to be na?ve, to be energetic. It is vital to continually attempt ventures that might end in failure. To quote one of my favorite poems,"Youth" by Samuel Ullman, "Years may wrinkle the skin, but to give up enthusiasm wrinkles the soul."

These exhibitions follow my near half-century career trajectory, ongoing and future projects, and various creative challenges. Both of these exhibitions trace my history from a professional boxer to a self-educated architect. Since launching my atelier in 1969, I have attempted to create a new world of design by repeatedly overturning preconceived aesthetic notions with architecture. As a globally active architect, I strive to undertake new endeavors and projects consistently.

We live in a time when the world is changing dramatically at an incredible speed, with the COVID-19 Pandemic disrupting our way of life. Despite these circumstances, I believe that it is vital to provide architecture and art to all people. Culture nourishes our minds and bodies and helps to color our lives with vibrance and passion. I think that this power will always have the potential to bring new value to human society in ways beyond our imagination.

FA:At the exhibition in fosun art center, you showed a lot of your world-wide project models. The globalization process has turned our world more homogeneous than ever. Under such circumstances, you have made much effort to respond to the cultural characters of each city and their relationship with the new architecture individually. We can see such effect in your projects, for example the giant egg in Osaka Nakajima from 1988 and the big glass box on Manhattan penthouse. They may even look quite in sane! Do you see these kinds of projects the rebellion against modern urban architecture? What is your move for reconcile the increasingly strong contradiction between globalization and localism?

Tadao Ando:Architecture is one of the products of an economic society. The client, together with the construction team, engages in a collaborative effort to realize the overall structure. This is done all while working to satisfy a variety of conditions – costs, legal regulations, deadlines – one by one. Within this highly sophisticated production system, one finds little leeway for expressive freedom, or in pursuing whatever "dream" one has in store for the structure. However, for me, the essence of architecture can be found precisely at these times – when one is locked in conflict, acting in defiance of restrictive conditions.

From time to time, I diverge from working within such societal frameworks, moving instead towards a pure, single-minded pursuit of the ideal architectural form. The most prominent example of this is the Nakanoshima Urban Egg Project, first announced in 1989. Without being commissioned, I began conceiving plans for a cultural complex – located in Nakanoshima in the heart of Osaka. At its center was the renovation project known as the Urban Egg, nested within the historic Nakanoshima Public Hall. My idea was to insert an ovaloid volume within the interior of this structure while leaving the original structure intact. Upon the inception of this concept, I began investigating a method to embed the memories of Osaka into the architecture of Nakanoshima, on to the future. I had no definitive agenda behind its realization. For this very reason, I dedicated myself to the drawings and models of this project– all in the hope of more boldly, more profoundly communicating a new type of architecture to the world. This type of architecture should respond to the physical, cultural, and historic landscape of "place" via a contextual dialogue. This discourse does not always imply notions of harmony or conformity with the environment. Daring interventions that wholly contradict their site with obtrusive idiosyncrasies can generate new interpretations of the city. Marvelous precedents for these ideologies were manifested in the architectural culture of the latter half of the 20th century with projects in Paris, from the Pompidou Centre to the Grand Louvre museum. Perhaps what is essential is to produce critical declarations towards existing institutions of urbanism and for buildings to act as emissaries of this uncompromising spirit. The purer this criticism and the more radical this architecture, the more it will challenge the order of society. A network of critical structures that overcome these conflicts can breathe life into the built environment.

FA:The development of the future global cities will have to face two major problems: flexibility and sustainability. In your opinion, which new technologies and materials will bring fundamental changes to the architecture of the future?

Tadao Ando:Environmental problems including those within the confines of the metropolis are ultimately caused by the imbalance between the artificial and the natural resources in the modern world. If we look at the solution to this problem within the realm of the built environment, we can arrive at two extremes: a "low-tech" world where we use significantly less energy and a "hightech" world where technology allows us to live compactly and artificially by consuming renewable energy.

Whichever direction we head in, our urban activities as a society will have to be restricted. The world must change. What is most important is for that change to share an awareness of issues and shifting values. Changing the framework of cities for a sustainable future cannot be achieved solely through the power of politicians, developers, and architects. We need to borrow the strength of every living person on Earth. Nature is not our right but a privilege. For the environment to grow, humanity must evolve as well.

FA:You have worked as an architect for more than half a century now. You describe yourself as a man who has fought and failed repeatedly. Like boxing, bidding requires power and strength, also a strong desire to beat the opponent. Can you share with us a project that means a lot to you?

Tadao Ando:The tense moments waiting for the bell to ring in a boxing match are uplifting yet nerve-racking. New building projects require the same mentality. In boxing, you must risk moving into danger to fully take advantage of your skills and eventually win the match. Creating something in architecture – not just building something but also creating something – also requires the courage to take risks. Taking that extra step forward into the unknown is vital.

When you are a boxer, you prepare for years for rounds that will only last minutes. It’s a fight, basic and primitive. Architecture, on the other hand, is a very long match, much longer than three minutes, but the tension must be maintained just as in boxing. Sometimes architects acquire a taste for fame and lose their discipline because they have forgotten the hunger of their early careers when you are the only one you can rely on. Boxing is a sport of pure stoicism and solitude; in the process of pushing your body and mind to the absolute limit, power is generated. Architecture is the same. Each project has a strict program and budget, and there might be little freedom to design. You must think through what is truly necessary and what needs to be built.

FA:Let’s talk about your China project. He Art Museum in Shunde locates in southern Canton. What is your understanding of the local architecture and culture? How do you integrate these traditions into your design of the art museum. What inspired your design at the first place?

Tadao Ando:I first thought of the building as the materialization of a single ripple spreading through a great body of water. The core is positioned at the node of the metaphorical "dropped pebble," its energy reverberating to its surroundings as the wave’s diameter gradually increases. This image gave form to four vertically stacked circular volumes growing in fixed increments. A three-dimensional arrangement of overlapping circles provides each space with a clear axiality and creates a varied and dynamic sequence that matches the city’s energy. The central core connects the entire concept together and becomes a symbolic and important space in the museum.

From the project’s infancy, the client decided to name the structure "He Art Museum" (He:和) as part of their desire to create a place of harmony and peace through art and culture. I fully embraced this idea throughout the design process. This appears in the various design features of the museum.

The entry sequence is designed with a dynamic contrast between the natural and the man-made to provide unique yet unexpected "surprises". Along the perimeter of the water feature are double-layered concrete walls veiled with plants. Creating depth in space by varying the circulation and visibility through the walls and greenery was inspired by traditional Chinese gardens. The significant water feature serves to reflect and harmonize the building with the landscape and urban environment. The culture of Lingnan exudes a unique sense of strength. He Museum was inspired by the tradition of Lingnan that has been strongly influenced by the ideas of the culture in Zhong shan of Central China. One of the goals of the design of the He Art Museum was to carry on the strength of Chinese culture. However, I sought to do this not by using traditional cultural motifs but by inheriting the spirit behind the culture. Particularly in the culture of the ancient Nanyue kingdom in the Lingnan region, the circle has been used in numerous disciplines, including architecture and art, as a symbol of harmony (yin and yang) and auspiciousness. The circular form represents a geometry rooted in the region’s vernacular.

FA:It took 5 years to prepare for the museum and 3 years to build it. What was the biggest challenge during the construction process? It is said that Mr. Aoki, who has been cooperating with you for a long time, was sent to the construction site at the final stage so that the project could finish successfully. I heard that after the museum was completed, you wrote a letter to the local construction team, could you tell us a little about the letter, what did you write?

Tadao Ando:The double spiral concrete staircase in the center of the He Art Museum is the soul of this architecture but was extremely difficult to execute well. The walls surrounding the stairwell support the spiral staircase and function as the core of the entire museum. It is designed as a symbolic spatial experience and as the structural core of the building.

There are always problems with architecture, regardless of size, but only when the team overcomes these problems is robust architecture born. A tenacious dialogue with Mr. Aoki at the construction site and the unwavering dedication of the local architect and the construction team made a high-quality structure possible. In any project, the local construction team directly addresses the problems that occur on the construction site. I am deeply grateful for the efforts of the client, local construction team, and local architect.

FA:Traditionally, architecture has been the collaboration between architects and craftsmen. However , the modern architecture has developed in such a niche way that architect and craftsmanship tend to be more separate. How do you see the value of handwork and craftsmanship? Can you share some stories of your collaboration with the local craftsmen during your numerous international projects? Are they all very different? What’s in common?

Tadao Ando:Initially in China, I tried to design and build as I did in Japan. Still, China has different values and cultures, so what can be made in Japan cannot be replicated precisely in China, not because of technical abilities but cultural differences. Through my architectural career in China for the past decades, I came to realize the country’s tremendous vitality and strength. The successful realization of many of my recent projects is a testament to the great leap forward in China’s level of construction technology today.

Each country I work in has differences in construction methods, types of materials, and cultural differences. The common thread through all of my international projects however, is a passionate client and construction team. Architecture is a team activity that requires the trust and collaboration between many talented and hardworking people to achieve.

FA:Among your numerous projects, have you ever made mistakes that you could not excuse or even failed entirely? Ater all, there is only one chance for concrete casting, are you nervous at the moment of opening the mold? Why do you love concrete so much? With the emergence of the new technologies and new materials, such as 3D modeling, will you consider more experiment in your future projects?

Tadao Ando:Concrete is a material symbolic of contemporary architecture. It can be found anywhere globally, but my passion has always been to use this material available everywhere to create spaces found nowhere.

The allure of concrete resides in its ability to vary based on location and beholder. With every use, the depth of expression can completely change. Le Corbusier used concrete as if it were clay, harnessing its plastic quality almost as if he were a sculptor. Louis Kahn used concrete as if it were hard as steel. The same material, two different effects. In the same way, I have searched for my own expression of concrete during my career, like the washi of the Japanese shoji.

FA:There are many similarities between the traditional houses in southern China and the Japanese architecture, such as the understanding of space. In Western architecture we usually experience the enclosed space, whilst the space in oriental aesthetic gives is mostly semi-open. One thing I reflected is that if we look at the traditional Japanese architecture, the relationship between sliding screens, through which the interior and exterior space of the building can be flexibly separated or connected. From the perspective of spatial relations, your architecture seems to be closer to the European architectural tradition where you play the game of light and shadow, the dramatic tension of space and the use of geometry. What is your approach to the tradition of the West or the East?

Tadao Ando:For me, the biggest difference in the architecture of West and East is light and ideas about solid and void. Light is a mirror that reflects the culture of place.

The history of building in Western architectural thought has been to puncture openings into stone masses to flood darkness with light. I think of the Pantheon in Rome, where the ever-changing streams of light flow through an oculus according to the sun’s movements, and the Monasteries of Senaque, where ultimate spirituality is attained through pure and ascetic light.

In the traditional architecture of the shimaguni (island country) of Japan, the existence of the "wall" to separate interior and exterior is nonessential due to its temperate climate. Japanese architectural devices like shoji act as wood and paper "umbrellas" under which we can live. The traditional light of Japan was not formed by the sun’s harsh rays but by komorebi (soft, dappled light) provided by the shadows. I am influenced by the light of both the East and the West.

FA:Modernism architectures emphasize the integration of form and function, however until this day, architecture as landmark has been the major pursuit. We have seen too many buildings with excessive form that inevitably at the cost of the function. What is your definition for a good architecture ? Today when we look at the modernist masters such as Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Louis Kahn and Wright, what new can we learn from them and what can we renovate?

Tadao Ando:Function separates architecture from all the other arts. By function, I do not mean how easy or difficult a building is to use. The question is whether or not the human proportion can be placed into the space of a building. It does not matter if it is an actual constructed building, an unrealized project, or even a proposal in which the architecture has given free rein to imagination. Architecture cannot exist without relating to human beings. The program from which architecture is generated, and an interpretation of the program are indispensable to architecture.

However, what constitutes the boundary between art and architecture? Artists are very courageous. They are stepping forward all the time. Architects must do the same. We must share the fear of challenging the unseen world. The combination of art and architecture can produce spaces of profound originality. By transcending the boundary between architecture and art, we can capture new kinds of free formal expression.

FA:You once said that you’d go back to where you started at the age of 75 and do small interesting projects. Your Row House in Sumiyoshi and Kobe 4*4 projects are very much such examples. They have rich architectural languages, very vital and full of tension, which is difficult to see in a large project. Do you still take on small commissions like this today?

Tadao Ando:Yes recently, I completed a project for the artist Taizo Kuroda, who sadly passed away this month. I designed a very small gallery of only 17 square meters for his ceramics, where his art is reflected in a shallow pool of water.

FA:So many houses you have designed, I am curious what kind of houses you live in? My architect friends all wonder what other hobbies you have besides physical exercise? I think you might be an ascetic.

Tadao Ando:I live in a highrise building five minutes from my office. I don’t think I would like to live in a building of my own design. Concrete is too hot in the summer and too cold in the winter!

One of my hobbies is planting trees and greenery around my hometown of Osaka. This began in 1996 with the Hyogo Green Network after the HanshinAwaji Earthquake of 1995. I have often heard that during earthquakes, large trees can save houses from collapsing. I made many visits to Kobe immediately after the earthquake, and when I first saw white magnolias in bloom in the first spring after the disaster, it seemed to comfort those who had lost their loved ones. While the local government had decided to create a housing construction project as part of the rehabilitation efforts, I conceived the idea for volunteers to plant two trees for each of the 125,000 planned housing units. By planting trees between buildings, I hoped that the greenery would create new communities and repair the townscape affected by the earthquake. Thanks to donations from residents and towns all over Japan, we were able to exceed our initial target and planted more than 300,000 trees. Since then, I have pursued other endeavors such as the Sea Forest in Tokyo Bay and the planting of cherry trees on Naoshima.

FA: There have been many Japanese artists and intellects in the 1960s and 70s who had great impact to the world art scenes. Tell us some of your deep impressions of the 1960s and 1970s, Kazuo Shiraga and the Mona-ha movements are among the most important ones. Shiraga’s work showed in He Museum is stunning. Have you some personal stories about these artists that you can share with us? How do you relate the avant-garde art of the time to your architectural practice?

Tadao Ando:A diverse array of artists gathered in the Gutai movement, which was established in 1954. Shuji Mukai drew endless hierographic symbols, and there was Takesada Matsutani who filled canvases black with pencil. Everyone in the group had eccentric personalities, including the founding members Jiro Yoshihara and Shozo Shimamoto, and others like Atsuko Tanaka and Sadamasa Motonaga. They did not behave like artists. They did not care about their lifestyles and only worried about expressing themselves as they pursued their own idiosyncratic expressions. For them, art was a way to break through the walls of existing social conventions and systems that constrained free thinking and to allow them to review things from the outset with their own eyes.

Beyond Gutai, I have had connections with artists and designers like Yayoi Kusama, Issey Miyake, and many others, whose spirit of challenge to explore uncharted territories in their respective fields inspired me. I think we get along so well because we walk the same path of challenging creation to the extreme. I believe that the"freedom" that permits such diverse interpretations is the"wealth" of art and that the scenery where such "freedom" is visible and hidden in people’s daily lives is the form of a truly prosperous society.

FA:Richard Long who is also my favorite artist has left a work on Naoshima. In my opinion, Ling’s walking on the earth surface are quite Taoism orientated, transcending spirit with harmony of body and mind. Do you remember Richard Long’s work in Naoshima?

Tadao Ando:Yes, actually, it is quite an interesting story. Mr. Soichiro Fukutake devised a plan to have Richard Long’s art in a museum I designed on Naoshima known as the Benesse House Museum and Oval. Mr. Fukutake has a solid sense of intuition and knew that if he were to leave paint and brushes next to an empty wall, Richard Long might pick them up and start drawing. It went exactly according to his plan, and now there are two unique artworks by Richard Long in the museums, drawn directly on the wall.

FA:He Art Museum’s exhibition showed works by Pablo Picasso, Ellsworth Kelly, Alexander Calder, Richard Long, Anish Kapoor and Damien Hirst, Kazuo Hoy, Chiyoshi Yoshihara, Ufan Lee and Hiroshi Sugimoto. There are amazing collections. Curator Shao Shu told me that in order to cooperate with your exhibition, you sent your team to look for artworks by these artists for the theme "Urban Hesitation". You eventually collected 8 pieces artworks among these artists. Incredible! These are almost priceless works! As a Chinese saying goes, a thousand pieces of gold are easy to get, but a friend is hard to find. You get commissions from consignés who would make other colleagues jealous and you keep friendly relationships with them. These friendships as well as your architectures have become legendaries. How did you make it?

Tadao Ando:In terms of art, my values are based on the memory of a vivid encounter with contemporary art in my youth. The action paintings of Jackson Pollock, the intelligent pop art of 1960s America, and Japan’s first global avant-garde art group, the Gutai Art Association. In particular, the influence of the artists of Gutai, with whom I was able to interact closely because we were all in the Kansai region of Japan, was significant.

As an architect, it is vital to maintain relationships with people. When you work alongside people who hold the same passion for their profession as you, there is mutual understanding and respect. I never seek to network but to learn from the people around me.

FA:The Naoshima project has lasted for 30 years. It has grown like creatures in the nature, perfectly illustrated your utopian imagination of architecture.

With the help of art, Naoshima, the abandoned islands has got a nearly eternal life. In the lecture you gave together with Mr. Yoichiro Fukuo and Mr. Lee Ufan at the 13th Shanghai Biennale -- ’--’ Recovery of Power from the Sea ’and the Rural Rebirth" showed excellent examples for the current rural construction and revival movement in China. The "Naoshima Mode" has also been brought by Mr. Fukuo to Peach Island in Shandong Province, China. Tell us something about your 30 years friendship with Mr. Fukuo.

Tadao Ando:I think you are referring to Mr. Fukutake. Naoshima began as an initiative born from the passion of President Soichiro Fukutake of Benesse Holdings, Inc.

For architecture to fully unify with nature, time and patience are required. The real challenge lies not in the design and construction of a building but the love and maintenance for it after it is completed. I believe architects have a responsibility to nurture their work so their buildings will mature with the passing of time. I have spent the last thirty years creating seven museums on Naoshima. I am profoundly invested in the architecture I have created on this island. Art, nature, and humans collide together to produce a thoughtprovoking experience that results in a place of endless possibilities. There, geometric architecture embedded in the Earth entices the imagination of its visitors and establishes a dialogue with art and its surroundings.

Nature conceals most of my structures on Naoshima. The external appearance of each of the buildings does not give any indication of the interior spaces. The visitor can shift their thought away from the building’s shape and focus on their feelings and spatial experiences on the relationship between art and landscape. There are also independent artworks spread throughout the island, where the nature of Setouchi sets a stage for each artist. Artists often create pieces inspired by the surroundings and invent works of art that are completely specific to their locations. The idea that the combination of art, architecture, and nature has the power to revitalize is consistent throughout all of the projects on Naoshima.

FA:Urban renewal and rural revival have become the important topics in China’s current and future planning. Many young architects find great playgrounds for them to realize their ambitions. When dealing with the urbanization and rural renovation, what suggestions would you give to them?

Tadao Ando:In a recent turning point of civilization, as an era of growth transitioned to an economic downturn, the prevalence of building renovation gained traction in Asian countries such as Japan and China, despite an enduring urban culture of continuously demolishing and reconstructing architecture. The spectrum of renovation spans from the restoration and preservation of cultural heritage sites to the conversion-like reuse of ordinary buildings. As disparate as these typologies of architectural revitalization may seem, they are both premised on the admirable idea of utilizing existing structures instead of demolishing them.

The essence of renovation should be the record and memory of the communal history which resides within the place. Examining metropolises like Paris or New York, we can observe that the aggregation of a city’s history fosters its culture. The past is conveyed through tangible objects rather than transferred information or virtual realities and forms a culture’s fertile "soil," establishing temporal continuities to the urban fabric. Of course, the older a building’s age, the more technical prowess, and economic energy will be required to restore and conserve it. At times, the efforts to protect a building’s record and memory may pose a the most significant obstacle in its effective reuse. Yet, I believe the objective of renovation is to inherit and pass on history to future generations. Its many benefits heavily outweigh the challenges regarding the excessive expenditure of labor and creativity. The frequent discourse between the traditional and the modern will evoke the interwoven urban fabric of time from past to present to future. Time and space fold within each other to ensure the continued sustenance of our cities for generations to come.

FA:Our FA Fortune Magazine has an architectural design section dedicated to introducing the rural construction projects of young architects in China. We have a "FA Young Architect Award" to encourage more young people, especially architects outside the mainstream schools of academic architecture, to participate in rural construction. Could you please say something to encourage these young people?

Tadao Ando:I would tell my younger self always to pursue endeavors that you think are challenging. Also, to never give up your dreams. I believe that your twenties, whether you choose to be an architect or not, are crucial years that impact life thereafter. Whether you can live your impressionable twenties with vigilance will determine if you will be able to live the life you desire by the time you reach your forties or fifties.

During this period, young people search for their ideals and create their own worldviews. You could say that this is when the self is created. During my own twenties, I encountered people and things that would eventually shape the core of my being and create who I am today. It was a time of forging close ties with others. The encounters in my twenties became directly related to my later work. When I was young, I had many friends who studied architecture at the University of Kyoto. Through them, I learned about the philosophers Tetsuro Watsuji and Kitaro Nishada, who gained a great deal of attention among students. Fate is a funny thing; in 1980 I created the Tetsuro Watsuji Memorial Hall in Himeji and have since been afforded the privilege of designing the Kitaro Nishida Museum of Philosophy in Ishikawa Prefecture. The various experiences that broadened my perspective during my youth speak to me today, as they have through the years.

FA:If you had not read the complete works of Le Corbusier, would you have been engaged in architecture?

Tadao Ando:I am not sure what would have happened. I try not to think about "what if" scenarios and always continue to move toward the future.

FA:May I like tell you a story about one of the winners of the first FA Young Architect Award? A young man from a village in Hunan province who had no education in architecture nor university. One day, he saw a book in a second-hand book stall in Beijing and decided to become an architect. To do so, he sold his apartment in Beijing and cut himself off from the outside world, working as an audit student in a university’s architecture department for several years. After winning the prize, he was nicknamed "the self-taught wild architect". This young man is Wang Qiuan. The book he saw was written by you. "Repeated Failure Repeated Fighting "