Spontaneous pneumothorax in a 17-year-old male patient with multiple exostoses: A case report and review of the literature

Koichi Nakamura, Kunihiro Asanuma, Akira Shimamoto, Shinji Kaneda, Keisuke Yoshida, Yumi Matsuyama,Tomohito Hagi, Tomoki Nakamura, Motoshi Takao, Akihiro Sudo

Koichi Nakamura, Kunihiro Asanuma, Keisuke Yoshida, Yumi Matsuyama, Tomohito Hagi, Tomoki Nakamura, Akihiro Sudo, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine, Tsu 514-8507, Mie Prefecture, Japan

Akira Shimamoto, Shinji Kaneda, Motoshi Takao, Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine, Tsu 514-8507, Mie Prefecture, Japan

Abstract BACKGROUND Multiple exostoses generally develop in the first decade of life. They most frequently arise from the distal femur, proximal tibia, fibula, and proximal humerus. Costal exostoses are rare, contributing to 1%–2% of all exostoses in hereditary multiple exostoses (HME). They are usually asymptomatic, but a few cases have resulted in severe thoracic injuries. Pneumothorax caused by costal exostoses is rare, with only 13 previously reported cases. We report a new case of pneumothorax caused by costal exostoses.CASE SUMMARY A 17-year-old male with HME underwent surgery for removal of exostoses around his right knee. Four months following the operation, he felt chest pain when he was playing the trumpet; however, he did not stop playing for a week. He was referred to our hospital with a chief complaint of chest pain. The computed tomography (CT) scan revealed right pneumothorax and multiple exostoses in his right ribs. The CT scan also revealed visceral pleura thickness and damaged lung tissues facing the exostosis of the seventh rib. We diagnosed that exostosis of the seventh rib induced pneumothorax. Costal exostosis resection was performed by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) 2 wk after the onset. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and there was no recurrence of pneumothorax for 2 years.CONCLUSION Costal exostoses causing thoracic injuries should be resected regardless of age. VATS must be considered in cases with apparently benign and relatively small exostoses or HME.

Key Words: Costal exostosis; Pneumothorax; Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery; Hereditary multiple exostoses; Case report; Treatment

INTRODUCTION

Multiple exostoses generally develop in the first decade of life and stop growing with skeletal maturity[1]. Exostoses most frequently arise from the distal femur, proximal tibia, fibula, and proximal humerus[2]. Exostoses of the ribs are rare, contributing to approximately 1%–2% of all exostoses in hereditary multiple exostoses (HME)[2,3]. Exostosis can transform into chondrosarcoma in up to 10% of patients with HME[4]. A differential diagnosis is Ewing sarcoma, which is more common among children[5]. Suggestive malignant costal bone tumor and worsening visible deformity are operative indications.

Costal exostoses are usually asymptomatic; however, in a few cases, they can induce specific yet severe symptoms due to the nature of the ribs. Costal exostoses have been reported to cause hemothorax, pneumothorax, pericardial injuries, diaphragmatic injuries, and visceral pleural injuries[6-9]. Surgical treatment was performed in many of these cases.

To the best of our knowledge, only 13 cases of pneumothorax caused by costal exostoses have been reported to date. Here, we report a new case of pneumothorax caused by costal exostoses that was successfully treated by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS).

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 17-year-old male with HME was referred to Mie University Hospital with a chief complaint of consistent chest pain.

History of present illness

The patient felt chest pain when he was playing the trumpet; however, he did not stop playing for a week.

History of past illness

The patient was diagnosed with HME at the age of 6 years and had undergone surgery for removal of exostoses around his right knee 4 mo before chest pain.

Personal and family history

The patient had multiple bony protrusions in the bilateral humerus, scapula, clavicle, fibula, tibia, femur, and ilium. The patient’s father had bony protrusion around his knees, but his family members did not undergo a full body skeletal imaging.

Physical examination

The patient’s temperature was 36.8℃, heart rate was 95 bpm, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 147/79 mmHg, and oxygen saturation in room air was 96%. There was no subcutaneous swelling, coughing, or sputum.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory examinations were normal.

Imaging examinations

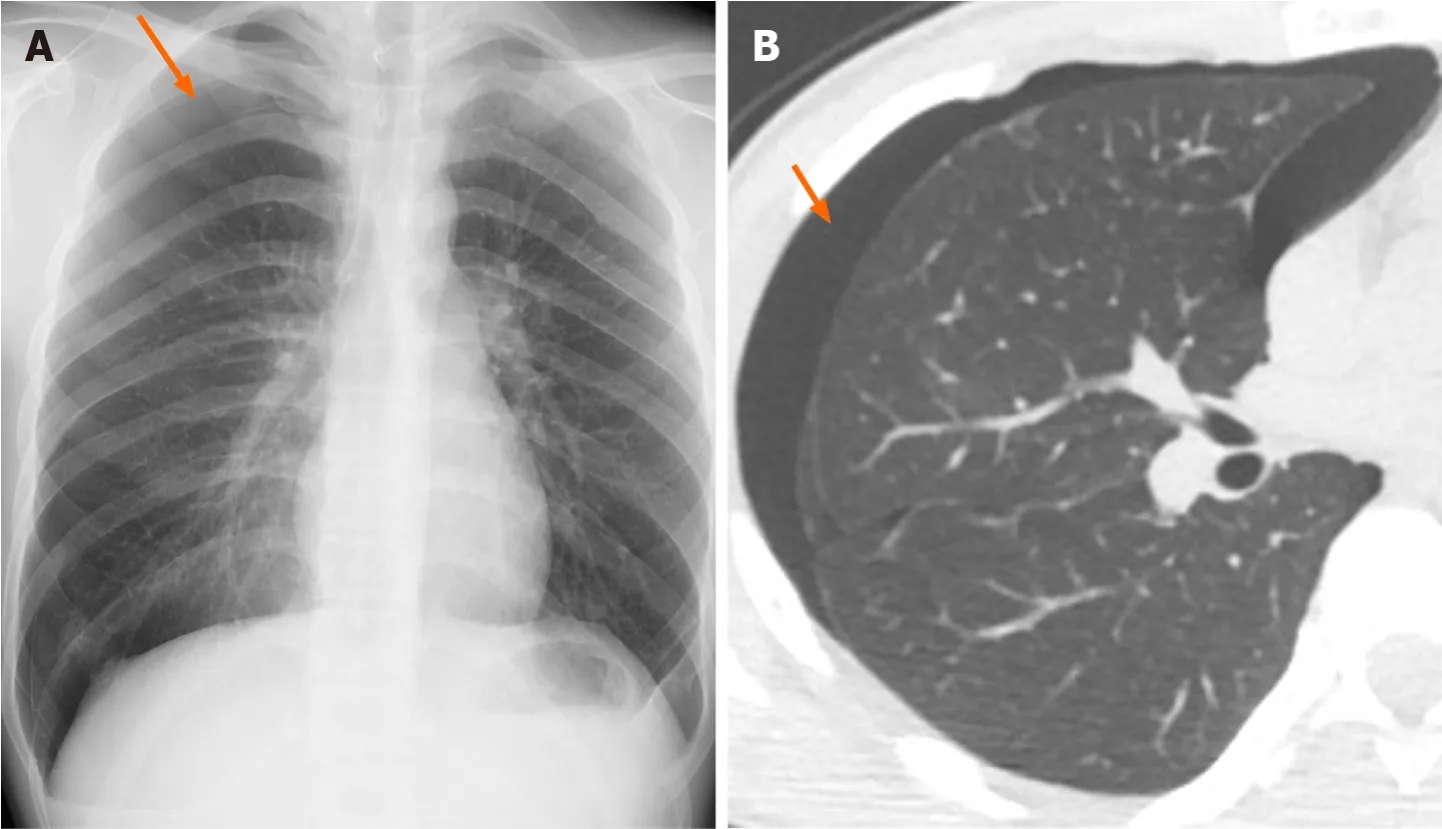

Chest X-ray showed right-sided pneumothorax (Figure 1A). Computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the presence of a pneumothorax (Figure 1B) and revealed four exostoses in his right ribs and one exostosis in his left rib (Figure 2). Exostoses arising from the right first and seventh ribs were protruded into the thoracic cavity; in particular, the exostosis from the right seventh rib was sharp and directly in contact with the visceral pleura. CT scan also revealed thickness of the visceral pleura and damaged lung tissues facing the exostosis of the right seventh rib (Figure 3).

MULTIDISCIPLINARY EXPERT CONSULTATION

Akira Shimamoto, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine; Shinji Kaneda, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine; and Motoshi Takao, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Pneumothorax caused by the exostosis of the seventh rib.

TREATMENT

A chest tube was not inserted because the sharp margin of the exostosis would have scratched the re-expanded lung again. Since the exostosis of the right seventh rib could potentially cause the recurrence of the thoracic complications, we decided to remove the costal exostosis.

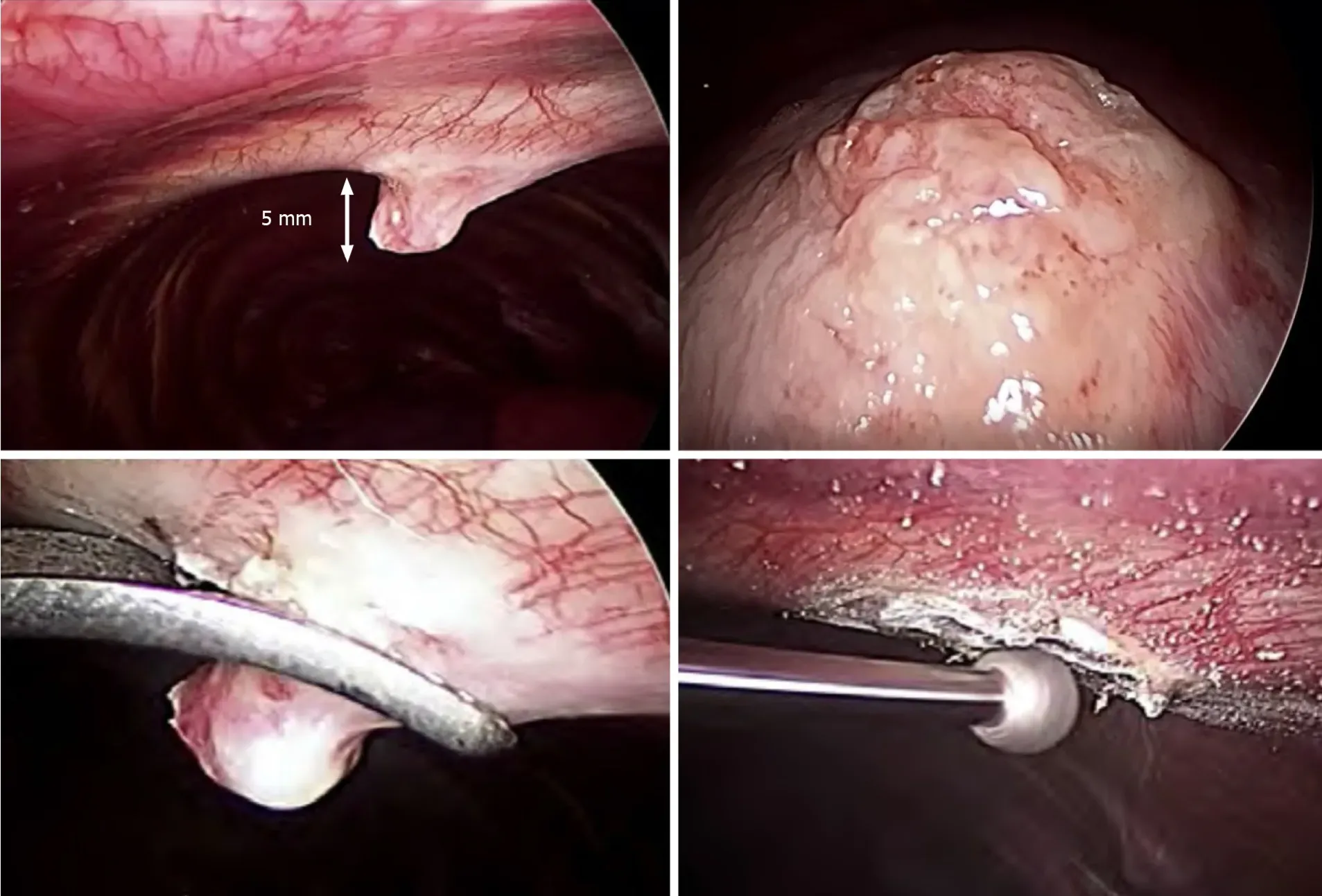

Resection of costal exostosis was performed by VATS 2 wk after the onset of symptoms. After induction of anesthesia, the patient was positioned in the left lateral decubitus position. The first incision was made in the midaxillary line of the right eighth intercostal space to insert the 5.5 mm thoracoport. A 5 mm camera was then inserted through the thoracoport, which revealed the bony protrusion of the right seventh rib; the protrusion was a bone mass measuring 5 mm in length on the midaxillary line directed toward the intrathoracic cavity (Figure 4). The second port was placed in the anterior axially line of the right seventh intercostal space to operate the forceps. Thoracoscopic observation revealed that the exostosis of the right seventh rib had sharp margins and the parietal pleura was lacerated; it was the apparent cause of injuries in the visceral pleura. The bony spur of the right seventh rib was removed using forceps and the arthroscopic burr was used to scrape down the spinous lesion. Other spurs were not treated because their edges were dull, and parietal pleura on the spurs was not peeled off. Mechanical pleurodesis was accomplished by abrasing the damaged visceral pleura using electrocautery. A 20 F chest tube was placed in the apex of the thoracic cavity.

Pathological examination revealed that the resected specimen was histologically composed of mature bone, hyaline cartilage, and fibrocartilage with no sign of malignant transformation (Figure 5). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of exostosis.

Figure 1 Chest X-ray and computed tomography scan revealed right-sided pneumothorax.

Figure 2 Computed tomography scan shows exostoses of five ribs.

Figure 3 Damaged pleura and lung tissues confronted with the exostosis of the right seventh rib.

Figure 4 Intraoperative findings and treatment.

Figure 5 Pathological findings (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and there was no recurrence of pneumothorax during 2 years of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

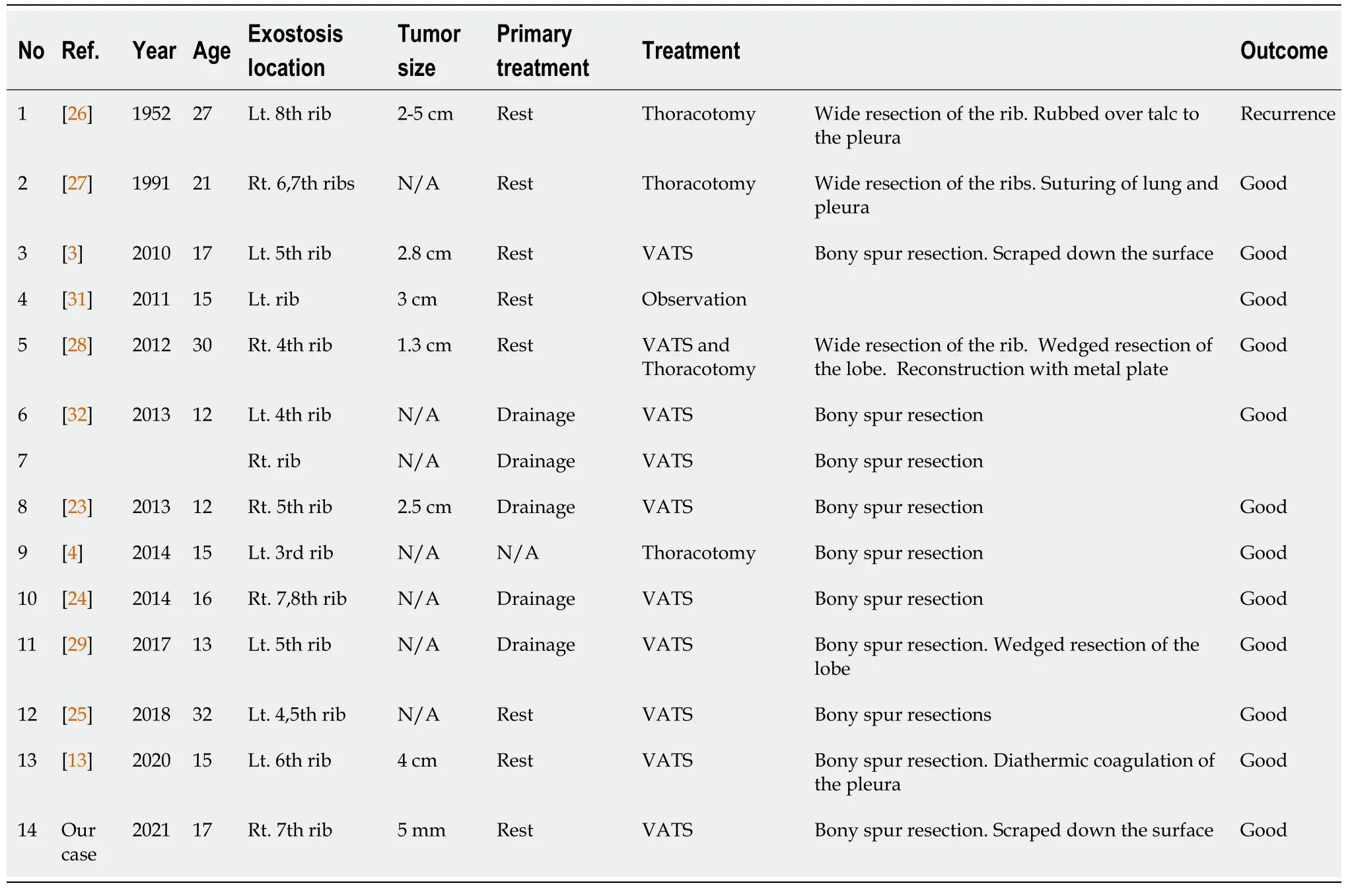

Most cases of costal exostoses are asymptomatic; therefore, thoracic complications caused by costal exostoses are rare[7,10,11]. Resection of costal exostoses has been reported for at least 87 cases, whereas hemothorax caused by costal exostoses has been reported in 38 cases. Pneumothorax caused by costal exostoses has only been reported in 13 cases. The details of which are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Review of the pneumothoraxes caused by costal exostoses

During review of literature, we found that tumor size was ≥ 1 cm in cases of pneumothorax or hemothorax caused by costal exostoses[3,6,12]. In our case, the maximum tumor size was 5 mm, which was smaller than that reported in previous case reports describing the thoracic complications caused by costal exostoses.

Significant traumatic events prior to symptom onset were not described in most of the case reports. However, a few patients with HME had a history of athletic activity and labor prior to pneumothorax[3,13]. In our case, pneumothorax might have been caused by a synergetic effect of the respiratory motion while playing the trumpet and the sharpness of the bony spur. In our case, costal exostoses were too small to be identified with chest X-ray; however, a CT scan revealed the presence of costal exostoses. Thus, a patient with HME who presents with an acute onset of symptoms in the chest should be assessed for pneumothorax and should undergo CT scanning to determine the cause of the symptoms in the chest.

Among the 13 previously reported cases, pneumothorax was treated with supportive care in the form of rest, wait, and see in seven cases; chest drainage in five cases; and unknown in one case.

In general, asymptomatic costal exostoses are not treated prophylactically[14]. Surgical management of costal exostoses is done for symptom control, establishing a histological diagnosis, and prevention of thoracic complications[4]. Among the cases reviewed by us, including our case, 13 cases required surgical treatment for costal exostoses.

Among all cases of pneumothorax, including ours, 10 cases occurred in patients under the age of 18 years. Of these, nine underwent surgery. Furthermore, the review of literature revealed that costal exostoses were actively resected in cases of thoracic complications caused by exostoses, even if prior to adolescence[4,15]. Thoracic complications caused by costal exostoses are serious. Therefore, similar to our case, regardless of age, risk aversion of thoracic injuries was considered more important than the risk of reoperation in previous case reports.

Compared to major thoracotomy, VATS has become an increasingly popular method for treating the intrathoracic lesions because it is a minimally invasive procedure[3]. VATS appears to be the best option for surgical resection of exostoses to prevent thoracic complications in cases of apparently benign exostoses[15,16]. In addition, VATS may be easily offered in cases of HME because redo VATS is less invasive[15]. The application of VATS for the removal of suggestive malignant exostoses has not been fully discussed; however, small tissue fragments may spreadaccidentally into the pleural cavity[15].

Thoracotomy is mainly done in cases of extensive rib resection. Thoracotomy enables surgeons to cope with active bleeding from the diaphragm[6] and bowel obstruction caused by the diaphragmatic ruptures[17] or malignant tumors[4]. Extensive rib resections or relatively large tumor resections are often performed with thoracotomy only or by mini-thoracotomy using thoracoscopic-guidance[18]. Among the cases reviewed by us, five had a tumor measuring ≥ 5 cm, and four were treated by thoracotomy[16,19-22] and one with VATS[20]. However, it seems that there is no correlation between age at the time of operation and operative approach[15].

Of the 14 cases of pneumothorax caused by costal exostoses, including ours, nine were treated with VATS[3,23-25], three with thoracotomy[4,26,27], one with a combination of VATS and mini-thoracotomy, and one with observation (Table 1). Of the 12 previously reported cases of pneumothorax since 2000, 10 were treated with VATS (83.3%).

Most case reports did not describe their method of resection in detail; however, in general, forceps or a rongeur was used. After bone spur resection, an arthroscopic burr was used to scrape down the spinous lesion in only one previous case and our case[9]. In our case, forceps in combination with an arthroscopic burr enabled us to treat costal exostosis by complete VATS.

Furthermore, review of literature revealed that the damaged lung tissues were treated by wedge resection of the lobe[28,29]. Mechanical pleurodesis was accomplished by abrasing the pleura with an electrocautery scratch pad[13,28]. A partial rib defect was reconstructed with a metal plate to stabilize the anterior chest wall[28]. In a 2-year-old girl, a Gore-Tex sheet was used to cover a 12 cm × 6 cm defect of the chest wall caused by rib resection[30].

Morphology of sharp tip of the exostosis and laceration of the parietal pleura are suggestive of the potential risk of lung injuries. The location of the costal exostosis is associated with lung injuries because the respiratory motion of the lower lobe is greater than that of the middle and upper lobe[24]. In our case, exostosis of the right seventh rib was removed due to the risk of re-injury of the lung. In contrast, other costal exostoses were not removed because their tips were dull, and no parietal pleura laceration was found. The spurs of the right first, third, and fourth ribs were not confronted with the lower lobe. Moreover, their spurs were less likely to grow further and re-injure the lung due to the completion of bone maturity.

The outcomes of surgical management of the costal exostoses were favorable in most of the cases with no significant complications, except for in two cases; pneumothorax recurred in one case reported more than a half century ago[26], and thoracic pain did not disappear for 2 years after surgery due to intercostal nerve damage in another case[15]. It appears that there is no correlation between age at the time of operation and recurrence of pneumothorax after surgery. In our case, VATS was successful and the post-operative course was uneventful; this was also observed in previous reports.

The present case has the following limitation: Postoperative follow-up period was short (2 years), and treatment experience was compared between different institutions and different times. It is necessary to investigate long-term results after the surgery.

CONCLUSION

We reported our experience of pneumothorax caused by costal exostoses because it is extremely rare. Damaged lung tissues due to costal exostoses should be suspected in HME patients with symptoms in the chest. CT scan was useful in diagnosing thoracic damage caused by costal exostoses. Costal exostoses causing thoracic injuries should be removed regardless of age; thoracic complications are serious, and there is no apparent correlation between age at the time of operation and recurrence of thoracic complications after surgery. VATS enabled us to resect the costal exostoses using a less invasive approach. VATS is worthy of consideration in patients with apparently benign and relatively small exostoses or patients with HME because redo VATS may be easily offered.

World Journal of Orthopedics2021年11期

World Journal of Orthopedics2021年11期

- World Journal of Orthopedics的其它文章

- Management of acute length-unstable Monteggia fractures in children: A case report

- Pathological humerus fracture due to anti-interferon-gamma autoantibodies: A case report

- Allergic dermatitis after knee arthroscopy with repeated exposure to Dermabond Prineo™ in pediatric patients: Two case reports

- Role of coatings and materials of external fixation pins on the rates of pin tract infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Femoral lengthening in young patients: An evidence-based comparison between motorized lengthening nails and external fixation

- Implementation science for the adductor canal block: A new and adaptable methodology process