Children as courseware collaborators:Using participatory research to produce courseware integrating science and sustainable development

Aurelio P Vilbar

University of the Philippines Cebu,Philippines

Abstract UNESCO’s2014 report oneducation for sustainable development(ESD),Shaping the Future We Want,shows that there have been worldwide advances in integrating ESD into school curriculums. Although there is a global curriculum in ESD, children as the end users of the curriculum are not actively involved in constructing sustainable discourses. Cognisant of children’s role in materials development, this research investigates how teachers can collaborate with children in producing teacher-made courseware using participatory action research (PAR). The study was conducted with 37 teachers enrolled in a graduate course on second-language teaching. Its goal was to produce courseware that promotes ESD and science concepts, such as global warming and the environment. Using PAR, the children collaborated with the teachers in designing the content. Interviews, focus-group discussions and surveys show that the courseware promoted excitement, science and ESD concepts, but suggested revising and trimming some videos and reading texts.

Keywords Education for sustainable development, participatory action research, content-based instruction, English-language teaching

‘Do not call us future generations when we are excluded in reality! In this age of climate crisis, we are the concerned party who has no rights (authority)but has to take all the responsibilities.’ (Kim,2019) This was the paradoxical outcry of the young people of Seongdaegol Community, Dongjak,Republic of Korea, who helped educate the community on energy conservation through the Seongdaegol Energy Saving Movement (Kim,2019). In this movement, adolescent village students analysed energy consumption and worked collectively with the community on their project Do-It-Yourself Mini-Solar Prototype. Through this assignment, solar lights were installed in community childcare and senior citizen centres and reading rooms.

The success story of Seongdaegol proves that children and other young people are not just consumers of knowledge but also active producers in constructing a sustainable world.It showcased a multidisciplinary approach,applying science,technology,public relations and education to promote sustainable energy consumption.The project manifests the goal of education for sustainable development (ESD),which is to transform society by helping people develop knowledge,skills and behaviours needed for sustainable development (UNESCO,2014b).Von Braun (2017)stated that education should not be guided by human capital formation for lifelong learning in the utilitarian market but for the recognition of children as contributors to the development of a sustainable society.

The case of Seongdaegol is not,however,a reflection of how ESD is being implemented in the curriculum worldwide.Although there are successful examples of ESD integration in the curriculum(UNESCO,2014a),in pedagogy and curriculum development (Laurie et al.,2016),and in building the capacities of sustainability leaders (Franco et al.,2019),the participation of children as the end users of ESD has not been widely exploited in curriculum and materials development (Donovan,2016).Donovan highlighted that children could collaborate with adult researchers on sustainability issues.Unfortunately,if children participate in curriculum and instructional materials planning (Shamrova and Cummings,2017),their participation is only in the first phase and they are often disengaged during the data analysis process.This implies that the views of children as collaborators and end users in the development of instructional materials have been silenced.

To promote more learner-centred instructional material,this research addressed the recommendations of Zhao et al.(2017) and Dell (2018) to use participatory action research (PAR) in developing ESD-and science-based interactive multimedia courseware (IMMC) in teaching Grade 8 students.Zhao et al.and Dell emphasized that curriculum developers need to use PAR to listen to the critical opinions and experiences of the children as users of and collaborators on the material.PAR is a dynamic research process that promotes dialogue and conscientization between the researchers and the participants as end users of the materials being developed(Balakrishnan and Claiborne,2017;Danley and Ellison,1999).

Conducting PAR with children can help in customizing instructional materials because the materials used in the classroom and in teacher training were designed by specialists who may have the subject-matter expertise but lack the localized socioeducational context (Mulà et al.,2017).In the Philippines,teacher training usually follows a topdown,one-shot,cascading model in which the curriculum and materials are designed by national or regional offices (Lomibao,2016;Oracion et al.,2020).PAR with children can contextualize such national or regional materials because it can connect theory and practice in participation with the respondents,who can offer practical solutions to problems(Reason and Bradbury,2012).According to the UNESCO report on ESD (UNESCO,2014a),participatory learning processes and problem-based learning are effective methods in ESD curriculum and materials development.

1.Content-based instruction

The method of using ESD and science concepts in English-language teaching is anchored in contentbased instruction (CBI),which uses academic content in language teaching (Snow,1998;Wesche,2012).Considered to be content-enriched,CBI has been widely used to promote a dual commitment to language and content learning,such as sciences or ESD,to support the diverse needs of language learners(Stoller,2004).In CBI,the content taught in English classes is non-language subject matter or topics that are closely aligned with other school subjects.These topics (e.g.recycling,geography) become the springboard in discussing linguistic,cognitive and metacognitive skills,as well as subject matter that students need in order to succeed in their learning endeavours(Stoller and Fitzsimmons-Doolan,2016).

CBI is also deeply grounded in the societal mission of education.Sato et al.(2017) held that,since the ultimate mission of education is to promote a sustainable society,students’ criticality should be nurtured by teachers who encourage critical engagement with ‘language’ and ‘content’ texts on various global issues.They stressed that content to be used in language teaching should take a sociocultural turn and have connections to other academic fields,education at large,and society.

In the courseware,science and ESD concepts were the obligatory content in teaching competencies in the English language.Topics on global warming,the environment,food security,cultural diversity and gender equality were used as a springboard in learning English vocabulary,appropriate verb tenses,subject–verb agreement and other grammatical knowledge.Videos on global warming and climate change were used as viewing text to develop children’s competency in making conclusions and generalizations.News articles about peatlands in Indonesia and global carbon footprints were used as grammar exercises in using the active and passive voices.

Using such authentic science texts promotes meaningful learning among the students and avoids the idea of teaching English for no obvious reasons(Jordan,1997).Substantial studies show that CBI is effective in promoting language performance,content learning and communications (Garner and Borg,2005;Laviosa,2020;Pessoa et al.,2007;Stoller and Fitzsimmons-Doolan,2016).

2.The English for Sustainable Development Project

This paper is part of a bigger project called the English for Sustainable Development Project,which aims to create a collection of IMMC to be used in teaching English as a second language to Filipino children.The courseware addresses the need for the revised junior high school English curriculum of the Philippines’ Department of Education to produce instructional materials that promote multiliterate,multimodal,inter/multidisciplinary and sustainability education (Department of Education,2016).

The new Philippine curriculum aims to develop digital literacy by drawing on informational texts and multimedia to build content and language knowledge,especially in viewing competencies.However,the technological support for education in the country has been more focused on providing computer infrastructure and integrating technology in the curriculum with teachers’ professional development (Tomaro and Mutiarin,2018).The production of localized IMMC has not been a priority.Thus,language teachers may have been adapting context-free but accessible global texts in teaching viewing competencies (Vilbar and Ferrer-Malaque,2016).

The courseware topic for this study is ESD,which aims to integrate values,activities and principles of sustainable development in education to respond to the world’s social,economic,cultural and environmental problems (Liimatainen,2013;UNESCO,2007).The goal of ESD is to improve the quality of life for all citizens of the world (UNESCO,2018).

As a limitation,the courseware focused on 7 of 17 themes from the United Nations Millennium Development Goals:environmental conservation and protection,sustainable production and consumption,health promotion,overcoming poverty,gender equality,cultural diversity and intercultural understanding and peace (SEAMEO INNOTECH,2010).The themes imply an inter-and multidisciplinary approach but rely heavily on science concepts,especially in the areas of global warming,climate change,disaster management and sustainable food consumption.

3.Research objectives

This research investigated how teachers can collaborate with children in producing teacher-made IMMC using PAR.The study was conducted with 37 Filipino teachers enrolled in a course in the Master of Education–English as a Second Language degree programme.The goal was to produce courseware that uses science and ESD topics in teaching grammar,reading and viewing competencies.

Using PAR,Grade 8 students collaborated with the teachers in designing the content,immediate feedback and graphical user interface (GUI).

This research answers two questions:(1) How are science and ESD concepts integrated into Englishlanguage teaching IMMC? (2) How did the participation of children help in the development of IMMC content and GUI?

4.The participants

This study involved three kinds of participants:(1)37 graduate school students,who were in-service teachers;(2) students of these teachers;and (3) my high-school students.Some teachers did not have classes when the pilot testing was conducted,so they requested that my students be their participants.

The in-service teachers were my students in graduate courses on second-language teaching.The courses were divided into three parts:second-language teaching theories and principles,courseware development,and pilot testing.The teachers used the authoring software Author Plus Pro from Clarity English (Hong Kong).

To meet ethical requirements for research,all of the teachers were consulted before the research was conducted and were given an alternative to create printed instructional materials if the courseware production was deemed to be too complicated.They all gave their consent to publish their courseware output,reflections and survey results during their pilot testing with their students.The courseware output and survey results were part of the course requirement,while the reflections were not graded.After the consultation,the agreement was included in the course syllabus and approved by the Graduate School Coordinator of the university.It was also stressed that teachers had the option of not continuing to produce the courseware if the task became too difficult.

For the Grade 8 students of the 37 teachers,their participation in the pilot testing was voluntary and not graded.The teachers provided them with laptop or desktop computers to use and to evaluate the courseware at their convenience.To protect the privacy of the teachers and students,pseudonyms are used in this paper.

Neither the teachers nor I own the copyright of some videos and reading texts used in the courseware,which is used only for research and not for commercial purposes.All sources were correctly acknowledged.

5.Methodology

As part of a larger research project,the courseware’s syllabus was developed through consultations among teachers,English-language curriculum experts and students.The syllabus was validated and published in a conference proceeding (Vilbar and Ferrer-Malaque,2016).

This paper focuses on children’s participation as collaborators in developing the courseware during the pilot testing and initial implementation.The pilot testing aimed to determine the children’s views on the courseware’s content and exercises before the formal implementation of the IMMC in the school.To gather data,it used an open-ended questionnaire,semi-structured interviews and focus-group discussions.

The open-ended questionnaire aimed to determine the extent to which the science and ESD concepts used in the courseware developed students’interest in learning the texts,promoted ease in reading and viewing,and were used in completing the exercises.It also determined whether the GUI and layout made it easier for students to complete the IMMC exercises.As supplementary data-gathering procedures,the semi-structured interviews aimed to determine the users’ experience in using the courseware.The interview questions focused on the readability of the printed and video texts,on words that hindered reading,and on the topics of and time required for the reading and viewing materials.

The focus-group discussions aimed to validate the users’ summarized answers in the open-ended questionnaire and semi-structured interviews.The teachers facilitated the discussions in groups of 5–10 students.Each student expressed their views on the following questions:

• Which of these ESD and science texts are the most or least interesting?

• Which are the most easy or difficult to understand?

• Which questions are the most easy or difficult to answer?

• Which of the tests require the most or least thinking time?

6.Results and discussion

This section presents the results of the participatory process between the teachers and the students in designing the courseware.It presents the courseware syllabus,the sample science-and ESD-based reading texts and exercises,and the evaluation of the IMMC in the pilot testing and initial implementation.

6.1.The courseware syllabus

The courseware is versatile:it can be used either in stand-alone instruction or in computer-aided instruction with the teacher.It is used via desktop or laptop computers.

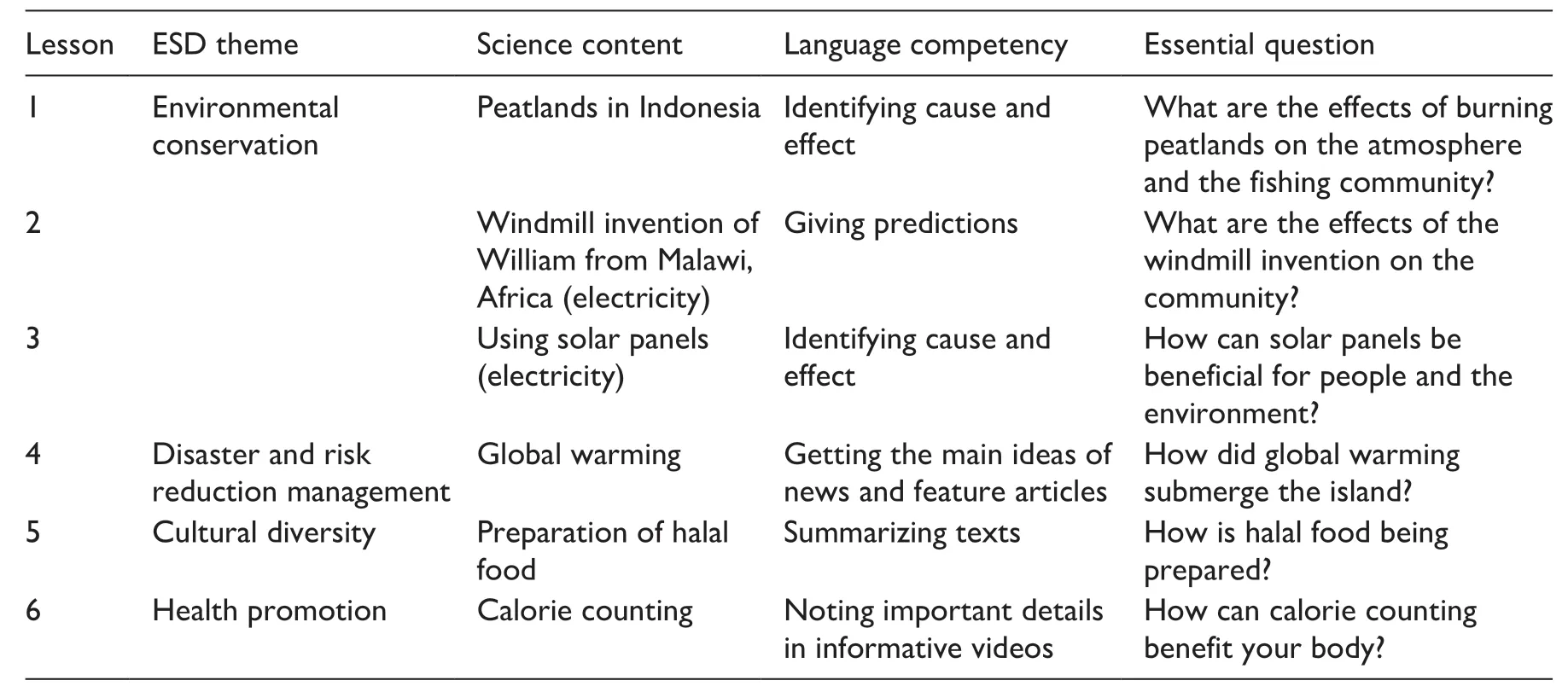

The courseware’s syllabus is divided into two modules:the ‘Viewing to Reading Modules’ and the‘Grammar Modules’.The modules follow this sequence:(1) Objectives,(2) Lessons,(3) Exercises and (4) Assessment.The content of the modules,which is related to ESD or science concepts,is shown in the sample syllabus in Table 1.The table highlights only the salient parts of the content.

Table 1. Salient points of the courseware syllabus.

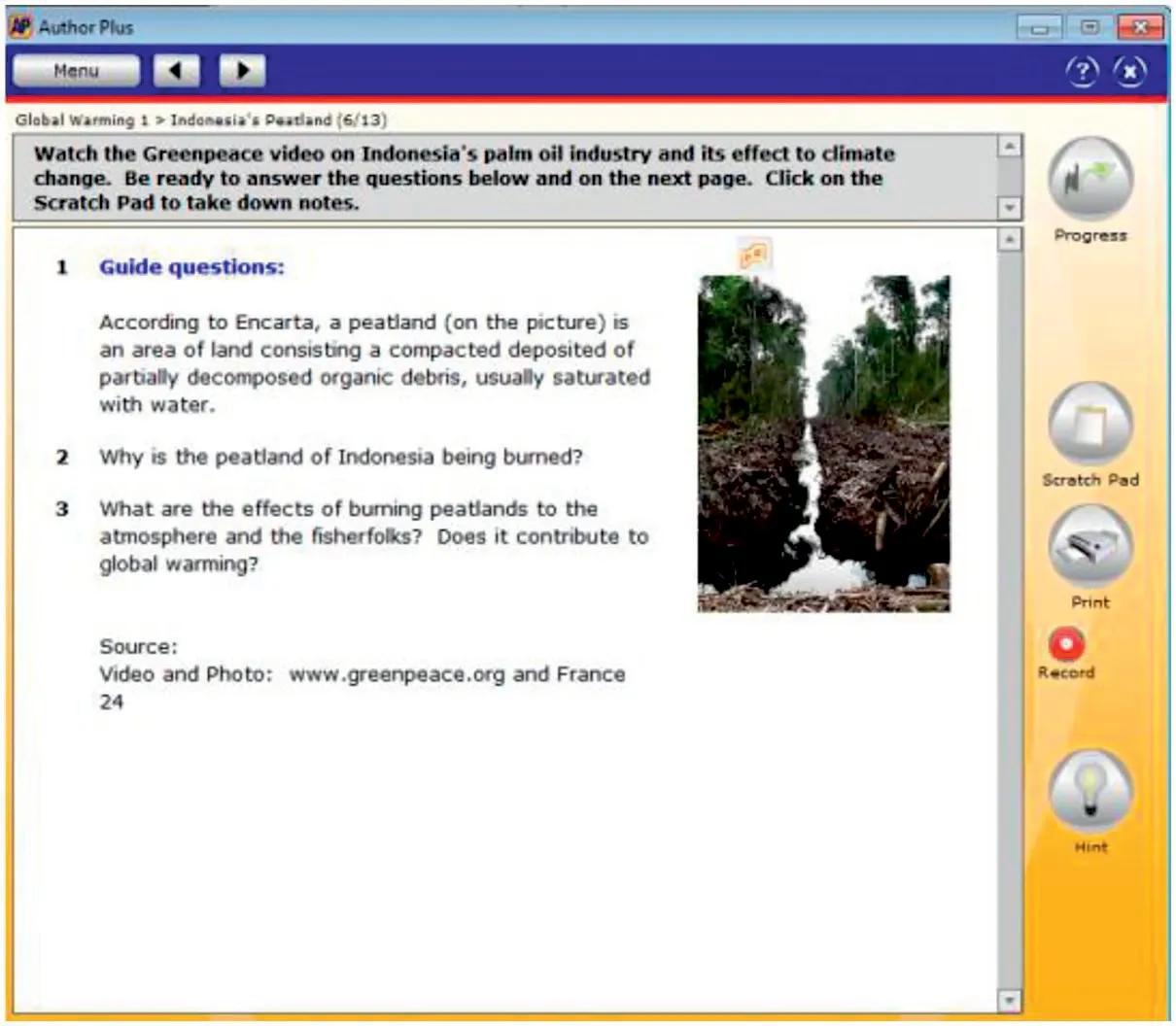

As shown in Table 1,Lesson 1,the news video about peatlands in Indonesia is used as the content in teaching the language competency of ‘identifying cause and effect’.

Table 2. Students’ qualitative evaluation of the IMMC.

As shown in Figure 1,students read the definition of peatland and ‘guide’ questions about why peatlands are burned.Then,they click on the video to watch and answer the questions.As shown in Figure 2,students answer a vocabulary comprehension exercise focusing on the effects of burning peatlands on wildlife and other inhabitants of the area.

In Lesson 2,the speech of the teenage windmill inventor,William from Malawi,Africa,is used to teach the objective ‘giving predictions’ and as a reinforcement activity for the lesson on ‘identifying cause and effect’,as shown in Figure 3.In this exercise,students analyse the parts of the windmill that produce wind power and the amount of electricity generated for William’s village.

One topic appealing to children is about a mystery island.As shown in Figure 4,students read a news article about New Moore Island,an island of which both India and Bangladesh claimed ownership.However,global warming ended their dispute by submerging the island,according to the article.After reading the article,students answer reading comprehension questions.

As shown in Figure 5,students watch a news report about a public school in the Philippines that used solar panels.Then,as a viewing comprehension exercise,the students discuss the benefits of solar panels for the school and the environment.

Figure 1. Viewing exercise:cause and effect of burning peatlands.

Figure 3. Viewing comprehension:windmills as a source of renewable energy.

Figure 4. Reading comprehension:effects of climate change on small islands.

Figure 5. Viewing comprehension:effects of solar panels.

From the syllabus and sample exercises,it is evident that CBI is a holistic pedagogy in teaching English grammar,reading and viewing competencies while also teaching the ESD themes and the science concepts of peatlands,greenhouse effects,carbon emissions,renewable wind and solar power,and climate change.The syllabus promotes a dual commitment to the learning of English language structures (Stoller,2004) in ‘identifying cause and effect’,using the content of peatlands in Indonesia.

The IMMC is anchored in the assertion of Eli et al.(2020) that the use of an interdisciplinary approach in teaching ESD across a range of subjects promotes a more holistic understanding of sustainability.It develops a seamless discussion of a sustainability issue–from the basic problem of global warming to the sustainable solution of using solar power.The courseware translates the ESD theories into practical pedagogical application and orients the students towards their larger responsibility for creating a sustainable future (Sato et al.,2017).It allows the students to critically reflect on texts and videos on sustainability issues.

6.2.Children’s participation in courseware development

In the pilot testing,the students used the courseware and shared their experiences via interviews,focusgroup discussions and surveys to improve the courseware’s content and GUI.The GUI is the interface of the courseware that allows users to interact with the computer through direct manipulation of various graphical elements and visual indicators such as menus,icons and navigation buttons (Jylhä and Hamari,2020).

6.2.1.Improvement of the content.Through this new experience of developing courseware and collaborating with the children,the teachers felt enthusiastic about measuring the opinions of the students.Findings from the interviews,focus-group discussions and surveys show that the children displayed more excitement towards the viewing lessons than towards the reading texts.This could be attributed to the novelty of using IMMC in teaching.For the video content,the majority of the children claimed that the lessons on the environment,cultural practices and women’s empowerment were educational,interesting and informative.The following excerpts demonstrate their evaluation:

Student A:‘Articles provide information about the current status of security around the globe.The courseware taught me that we should not waste resources.’

Student B:‘I learned how important cultures are.Nowadays,the rate of cultural preservation sank because of modernization.The courseware preserved cultures by reading and viewing articles.’

Student C:‘I know the effects and disadvantages of global warming.We should reduce our release of carbon dioxide ...which can damage our resources.’

Student D:‘The courseware voiced out the role of women to our society.Women hold crucial roles in the development and destruction of a society.When women are given the right to education,then they can create a better future.’

Student E:‘I learned more about El Niño and La Niña in the courseware.’

The children approved of the video content and considered it essential to create a sustainable world.Some shared their dismay about malnutrition and poverty around the world but were curious about various global indigenous practices and sports.Their excitement about learning with videos demonstrates the ability of multimedia to enhance student learning and digital skills (Schmid and Petko,2019),student engagement and learning (Coyne et al.,2018),motivation and learning (Liao et al.,2019),and positive attitudes towards learning(Alsalhi et al.,2019).

Although the participants claimed that the reading lessons promoted relevant information about sustainability,most of them considered the assignments to be boring,tiring and long.Many of them suggested using shorter reading texts.However,the experience validated studies that have found that reading on paper promotes better reading comprehension than reading on a computer screen (Kong et al.,2018;Støle et al.,2020).

What was rewarding about the collaboration with the children was their honesty and integrity about the science content.They felt that reading articles on global warming or solar power was a boring experience but that watching videos about climate change was educational.This conflicting reality made us realize that offering the same topic using different modalities can yield different levels of comprehension and appreciation.For example,the children preferred viewing a scientific video about a carbon footprint to reading about it.

This experience added to our understanding of materials development that integrates science concepts,especially in terms of selecting the mode of content delivery.The alignment of video content and instructional design to learning outcomes is a complex process (Bétrancourt and Benetos,2018) that needs more investigation.Digital reading has fewer benefits than paper reading when the reading materials are informational texts (Delgado et al.,2018).In the courseware,most reading materials were categorized as informational texts,such as those discussing sustainable food consumption and calorie counting,peatland burning and greenhouse gas emissions.

These types of texts develop global and scientific knowledge but are considered cognitively demanding and require active reading strategies (Mariage et al.,2019;Santoro et al.,2016).This process of improving the courseware content through children’s participation proves the importance of participatory learning processes in creating ESD materials (UNESCO,2014a).

Some recommendations from the children were not fully followed due to the required learning competencies that the courseware needed to achieve.For example,putting subtitles on all videos was not done because some of the videos were designed to develop the required competency of ‘note-taking of events’ or‘vocabulary’.The teachers and I agreed to put subtitles on videos that required a strong and technical science background and on videos that used unclear language.For instance,the video on global warming that focused on carbon emissions statistics had a subtitle to promote the scaffolding of the science-based topic.

This decision conforms with the findings of Pujadas and Muñoz (2019),who concluded that embedding subtitles in videos depends upon the language competence of the students to comprehend the video and the goal of the instruction.The subtitles can help both the students and the English-language teachers to understand the technical context and jargon of the topic.Furthermore,they can promote reading ease and appreciation of the lesson rather than explicitly discussing all the jargon before,during and after watching the video.

6.2.2.Clarifying the level of difficulty.As adults,teachers may have different experiences or schemas of the content’s level of difficulty.The children’s participation helped to clarify the viewing and reading content’s levels of difficulty,familiarity and interest.For example,at first,the teachers were uncertain about including a video commercial featuring Thai football players who lived in a fishing community.The video had a message of diversity,but all the dialogue was in Thai,so it could not promote competence in oral English fluency.However,when it was shown to the students,all of them were happy to watch the video.When they were asked to summarize the video,they could recall in English the elements of the plot.

What the teachers perceived to be difficult or complex was proven otherwise by the children.This experience demonstrates the beneficial effects of PAR in materials development.PAR allows the narratives and feelings of the children to be heard in courseware development (Dell,2018;Zhao et al.,2017).It empowers the end users and participants to decide on the materials they will learn (Balakrishnan and Claiborne,2017;Danley and Ellison,1999).

The children also stated that the article on the Kyoto Protocol was interesting but too difficult to appreciate.They said that the words were mainly jargon that was difficult to understand in one reading.When the teachers and I reviewed the article,we realized that it was too technical because of its sociopolitical–legal nature.This difficulty in reading sustainable development texts is common in internationally produced ESD materials (Kioupi and Voulvoulis,2019).This could be due to the nature of the texts,which have sociopolitical undertones that are context dependent.

To improve the article,the teachers subjected it to readability testing and revised some words into understandable English without sacrificing the content.We also added a pre-reading activity that focused on the technical terms and their definitions.

The teachers’ action of revising the article shows that PAR can transform material to make it more learner centred and comprehensible to promote a wider appreciation of the content by the end users.Listening to the critical opinions of children as collaborators enhanced the ESD IMMC (Dell,2018;Zhao et al.,2017).In response to the children’s sincere comments,the text was revised to match the students’ cognitive level,and a pre-reading exercise was created to promote scaffolding.This collaboration between the researchers and the participants as end users of the material created more humane and child-friendly courseware (Balakrishnan and Claiborne,2017;Danley and Ellison,1999).

6.2.3.Improvement of the GUI.Asked about the GUI,the children were generally satisfied with the layout of the video,reading texts and navigational buttons.Only a few suggested making the font size bigger and changing to a lighter background.Perhaps this was because the children were accustomed to customizing their gadgets into dark or light backgrounds.However,this is a limitation of the courseware.It has only one default lighting background that is not adjustable.

What was noticeable in the pilot testing was that students did not perform well when doing longer reading exercises that required scrolling down the page.Student E said,‘Scrolling down to read more information is not helpful.’

When asked about this action,many claimed that scrolling was too inconvenient for them.Student F shared,‘I didn’t know there were more items to answer.I thought it was only five.I didn’t scroll down.’ Student G explained,‘It is more practical for me to read and answer exercises that are shown in one screen only,like a true-or-false test.’

This experience of scrolling is a common issue in multimedia design (Støle et al.,2020) and is a limitation of the courseware’s interface and setting.It does not offer links for students to access on the internet.This means that all reading texts are contained on the screen,which requires scrolling up and down.However,these comments from the children allowed the teachers to reflect on and to revise their choices in the multiple choice section without sacrificing the required competencies of the lessons.

6.2.4.Students’ qualitative evaluation of IMMC in the implementation stage.After the collaboration and revision,the courseware was implemented in a Grade 8 English class of 39 students in a state university high school in Cebu,Philippines.The courseware was used as the primary instructional material for learning specific English-language competenciesfor one month.The teacher served as the facilitator of learning while the students were using the courseware on their individual computers in school.

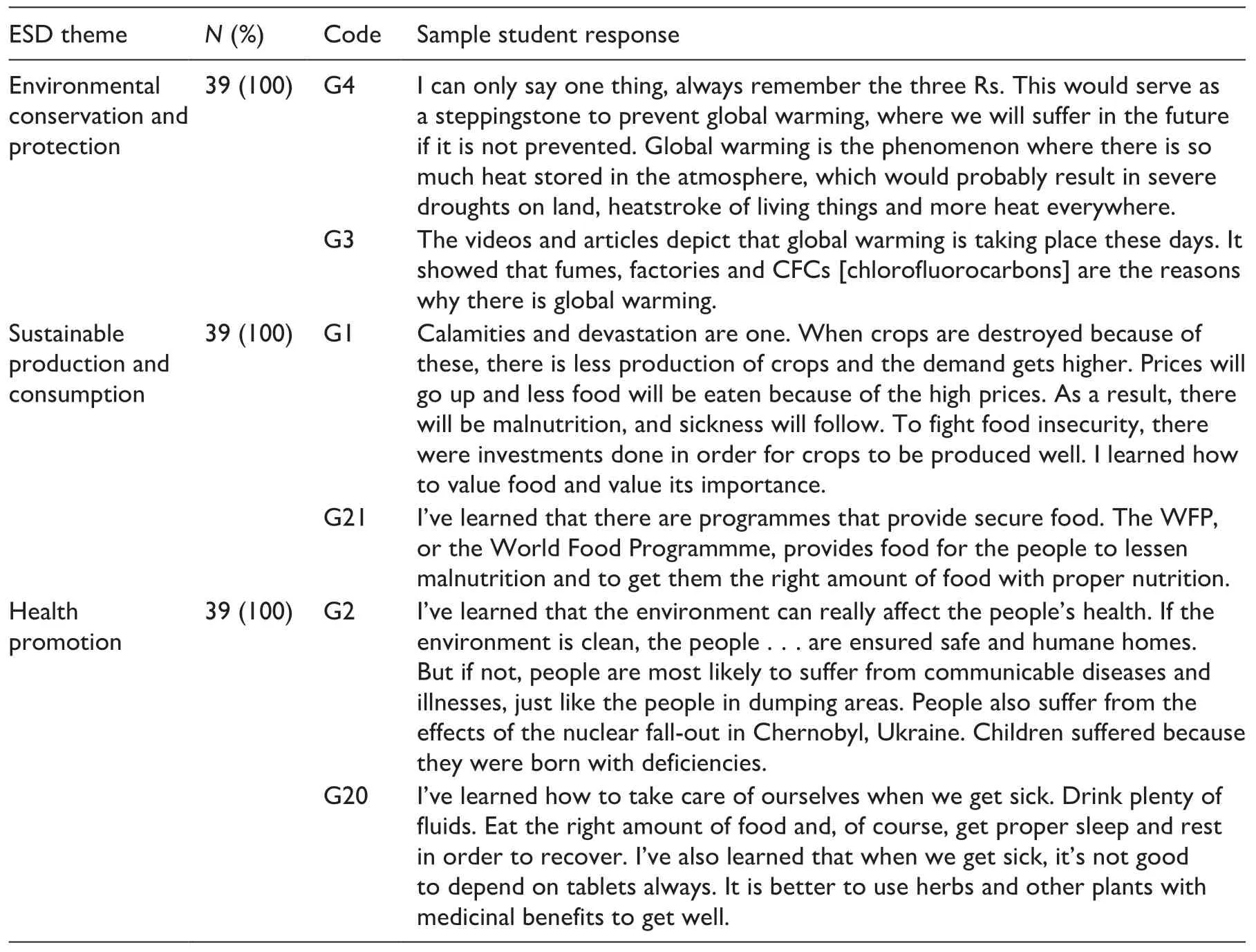

An open-ended questionnaire and focus-group discussion were conducted with the students to determine their experiences of using the courseware.The findings show that the courseware promoted the seven ESD themes of environmental conservation and protection,sustainable production and consumption,health promotion,overcoming poverty,gender equality,cultural diversity and intercultural understanding and peace.Table 2 shows sample statements taken from the questionnaire.

Table 2 shows that the children claimed that the courseware promoted ESD and science concepts.Student G4 shared that global warming was caused by fumes and CFCs,while G3 added that global warming is a phenomenon in which there is too much heat in the atmosphere.G4 suggested doing the three Rs–reduce,reuse,and recycle–to prevent global warming.

For sustainable production and consumption,student G1 shared that when crops are destroyed by calamities,their supply and demand are affected.G21 added that the World Food Programme provides proper nutrition to fight malnutrition.G2 discussed the relationship between a clean environment and people’s health.G20 advised that we should not be too dependent on using drugs to treat sickness but should instead use herbs and other medicinal plants.

The reflections prove the importance of conducting PAR among children before implementing the curriculum and instructional materials with them.The end users did not complain about experiencing difficulty in comprehending the reading materials on global warming and CFCs because these texts had undergone readability testing and revisions during the pilot testing.They were revised based on their reading level and were shortened,as recommended by the children.The whole experience of ease of reading supports the assertion of Zhao et al.(2017)that listening to the critical opinions of children as collaborators can promote the development of learner-centred material.

The children’s active critiques in the pilot testing made the courseware’s topics on sustainability and science more appropriate to their cognitive level and sociocultural needs (Macdonald,2012).Thus,the ESD and science topics,which were deemed to be complex and ambiguous (Kioupi and Voulvoulis,2019),gained acceptability among the student end users.This is validated in the reflection of student G3:‘The courseware showed that fumes,factories and CFCs are one of the reasons why there is global warming because of the greenhouse gas that is produced.’

The students’ positive evaluation proved that the use of IMMC in teaching sustainability among younger students is beneficial.The data confirmed some studies that found that the use of innovative and interactive digital pedagogies with inquiry can contribute to successful ESD contributions (see e.g.Cebrián et al.,2020;Ricard et al.,2020).The interactive feature of the IMMC aroused the interest of the students to learn these technical concepts (Zeti et al.,2020).

When educational digital materials use sound interface design,content and activities,they have the potential to improve the learning process (Zeti et al.,2020).IMMC can be an effective strategy in stimulating students’ interest in learning vocabulary related to science or ESD concepts (Yue,2017).

It is therefore feasible to use CBI in Englishlanguage teaching.The Grade 8 students learned not only language skills but also ESD and science topics,which are required in the curriculum.These science concepts prepared the students in their academic reading in their biology and social sciences classes.This research shows that CBI can promote multiliteracy through learning language content,science and technology (Snow,1998;Stoller,2004).

7.Conclusion

We can draw the following conclusions and make the following recommendations on using PAR with children as collaborators in developing science-and ESD-based IMMC.

CBI promotes an interdisciplinary approach in developing IMMC because it develops a dual commitment to the learning of English language and the learning of science-and ESD-based concepts.The IMMC content does not only focus on the superficial structures of language but also empowers the users to critically reflect on sustainability issues and perform sustainable actions.The integration of sustainability in the IMMC before,during and after the lessons promotes explicit instruction on the obligatory science content.The contents become the springboard and motivation for review lessons for language instruction.They become the topic in discussing English-language competencies and grammar and the theme for written assessments or quizzes.The IMMC aims to develop communicators with scientific knowledge of sustainability and a willingness to take greater responsibility for creating a sustainable world.

The use of PAR with children improved the IMMC’s GUI,delivery of instruction,choice of topics,the length of written texts and videos,and the number of exercises.The collaboration with children in the pilot testing and implementation stage allowed us to customize the IMMC based on the children’s preferred learning context without sacrificing the mandated learning competencies.The children suggested that the entirety of the reading texts and quizzes must be seen completely at the first glance.They added that scrolling a cursor up and down with a mouse was inconvenient and might make them miss other items.On the question of jargon or technical vocabulary related to science and ESD concepts,the children suggested that we explain the meaning of such terms before they read or view the selection in order to buttress their reading or viewing comprehension.

We recommend that language curriculum and instructional material developers use CBI as an interdisciplinary approach in developing contextualized digital materials.They can conduct a needs assessment with their students to determine the choice of topics or themes on which they can anchor their students’ language competencies.In addition,they can use PAR and collaborate with their students on academic topics or interesting social issues that can be used as a springboard for the lessons and assessments.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the University of the Philippines Creative Writing and Research Grant,the University of the Philippines Cebu Master of Education Program,and the University of the Philippines High School,Cebu,for their support for this research.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,authorship,and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research,authorship,and/or publication of this article.

- 科学文化(英文)的其它文章

- Building scientific capacity in disaster risk reduction for sustainable development

- Scientific literacy,public engagement and responsibility in science

- Working together to address global issues:Science and technology and sustainable development

- On the role of global change science in sustainable development:Reflecting on Ye Duzheng’s contributions

- Fostering spatial thinking skills for future citizens to support sustainable development