Challenges in the discontinuation of chronic hepatitis B antiviral agents

Apichat Kaewdech, Pimsiri Sripongpun

Apichat Kaewdech, Pimsiri Sripongpun, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai 90110, Songkhla, Thailand

Abstract Long-term antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis B patients has been proven to be beneficial in reducing liver-related complications. However, lengthy periods of daily administration of medication have some inevitable drawbacks, including decreased medication adherence, increased cost of treatment, and possible longterm side effects. Currently, discontinuation of antiviral agent has become the strategy of interest to many hepatologists, as it might alleviate the aforementioned drawbacks and increase the probability of achieving functional cure. This review focuses on the current evidence of the outcomes following stopping antiviral treatment and the factors associated with subsequent hepatitis B virus relapse, hepatitis B surface antigen clearance, and unmet needs.

Key Words: Viral hepatitis B; Relapse; Retreatment; SCALE-B; Stop treatment strategy; Nucleoside analogs

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major health problem globally; approximately 292 million people are affected by this virus[1]. Patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection are at risk of developing long-term liver-related complications,e.g., cirrhosis, decompensation, and malignant liver tumors[2]. Although the prevalence of CHB infection has declined as a result of immunization programs, the majority of Southeast Asian countries are still categorized as intermediately to highly endemic areas[3]. HBV replication occurs through the formation of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), and the persistence of intrahepatic cccDNA is the major reason for disease chronicity and a major obstacle for the eradication of HBV[4]. However, the measurement of intrahepatic cccDNA is not practical in clinical practice as it can only be done through liver biopsy.

Long-term nucleos(t)ide analogs (NA) inhibit the reverse transcriptase activity of viral polymerase and effectively inhibit HBV replication, reverse liver fibrosis, and reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[5,6]. However, NA have no direct effect on intrahepatic cccDNA or virus transcription in the liver. Therefore, because functional cure, defined as hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) clearance with or without anti-HBs seroconversion, is not often achieved, and most patients need longterm or even lifelong NA therapy[7].

Currently, the best time to stop NA therapy before HBsAg clearance is still uncertain because of the high rates of nontreatment recurrence. For instance, the pooled analysis of a systematic review showed a virological relapse (VR) rate of about 50% to 60% within 12 to 36 mo after drug withdrawal[8]. Although recent clinical guidelines suggest that some patients may stop taking NA before achieving HBsAg serum clearance[9-11], sensitive and reliable biomarkers for identifying patients with low recurrence risk have not yet been established[12,13]. This review focuses on both benefits and risks of discontinuing antiviral agents, as well as the current recommendations, factors, and novel biomarkers for predicting outcomes following NA cessation, and unfulfilled demands.

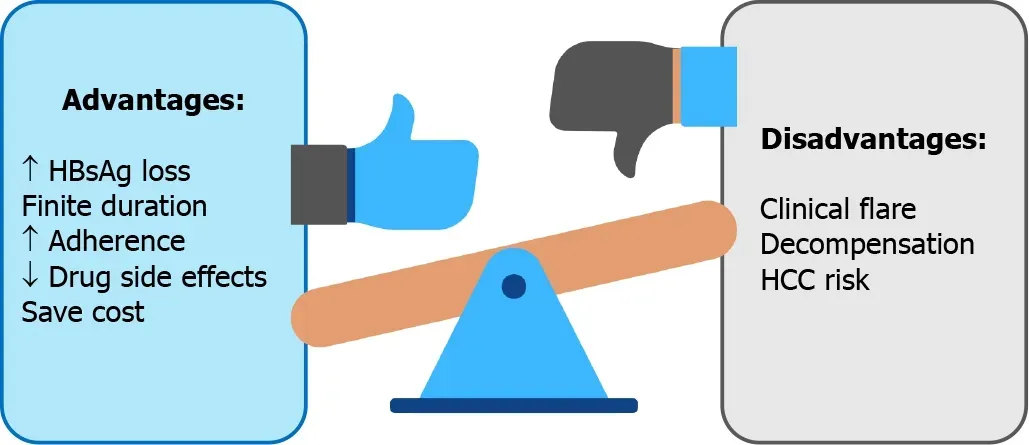

ADVANTAGES VS DISADVANTAGES OF ANTIVIRAL AGENT DISCONTINUATION

Benefit and risk concerns of CHB antiviral cessation are summarized in Figure 1.

Advantages

Increased HBsAg loss:The ultimate goal of CHB treatment is clearance of intrahepatic cccDNA. Nonetheless, this endpoint seems to be unrealistic with the current treatment options[9-11]. A more pragmatic endpoint is HBsAg loss with undetectable HBV DNA or a so called “functional cure,” yet HBsAg loss is rarely achieved with long-term NA therapy. In a French study of 18 CHB patients with NA treatment, the annual decrease of HBsAg levels was only 0.084 log10IU/mL[14], with a study-derived model predicting that HBsAg loss after continuous treatment with NA would be achieved in 52.2 years.

On the other hand, cessation of NA therapy may increase HBsAg clearance. An initial study by Hadziyanniset al[15] showed a high rate of HBsAg loss of 39.4% at 6 years after stopped adefovir (ADV) in hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) negative CHB patients. That study was followed by a peak of interest in NA discontinuation[15]. A recent systematic review including 1085 patients reported a rate of HBsAg loss of approximately 8%[8]. In contrast, a subsequent study reported HBsAg loss in a minority of patients on continuous NA therapy, approximately 2.1% after 10 years of follow-up[16].

Finite duration:Generally, long-term treatment with NA is required, in contrast to the definable duration of interferon-based therapy, 12 mo in HBeAg-negative, and 6-12 mo in HBeAg-positive patients[17]. Even though the side effects after several years of medication are very few, they can be problematic in real-life practice. An attempt to define a limited duration of NA therapy was first proposed in the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) 2008 guidelines[18]. Finite duration may increase drug adherence, lower the chances of developing side effects from the drug, and reduce costs[19].

Figure 1 Advantages vs disadvantages of antiviral agent discontinuation in chronic hepatitis B.

Increased adherence:Longer use of NA treatment is associated with lower medication compliance. Drug adherence is of concern in real-life practice[20]. Poor antiviral agent compliance is associated with emerging resistance, particularly in agents with a low genetic barrier[21]. A large retrospective study that included 11,100 CHB patients in the United States found a rate of adherence of 87%[20]. Moreover, a systematic review and meta-analysis included of 30 studies reported that the long-term adherence rate was only 74.7% after a median follow-up of 16 mo[22]. Notably, it was suboptimal compared with a good adherence rate of 95% defined in previous studies[20,23-25]. Compliance to antiviral agent use may improve with finite duration of treatment.

Decreased side effects:A recent systematic review indicated adverse events associated with NA were not common. However, some events were fatal, especially mitochondrial toxicity[26]. Long-term treatment with NA potentiates renal and bone side effects, particularly in tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and ADV users. In addition to the well-known side effects of tubular dysfunction and Fanconi syndrome associated with TDF and ADV, the real-world data also found that the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) declined more quickly in TDF and ADV users than in untreated CHB patients[27]. Despite the observation in recent registration trials that tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) had significantly lower rates of bone mineral density and eGFR reduction compared with TDF[28,29], making it is safer for long-term use, the reported safety data were from follow-up of no longer than 96 wk[30]. Therefore, whether TAF is truly safe for extended treatment is yet to be confirmed. Nonetheless, as shorter time of exposure to NA would decrease the risk of side effects.

Cost savings:As mentioned above, hepatitis B treatment with NA might be a longterm therapy. According to a survey in Singapore, fewer than half the patients preferred lifelong treatment[31]. One of the most concerns of lifelong therapy is the cost of treatment. Moreover, only about a quarter of the patients were willing to pay for lifelong therapy, with an acceptable daily cost of 8 United States dollars.

Disadvantages

Clinical flare and decompensation following off-therapy:The concerning issue after NA discontinuation is HBV flare, especially clinical relapse (CR). Most studies defined CR as an off-therapy HBV DNA > 2000 IU/mL plus an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level > 2 times the upper limit of normal (ULN)[8,32]. The overall CR rate from a pooled data analysis with a follow-up ranging from 12-69 mo duration after NA discontinuation was 34.6% in which CR was higher in HBeAg-negative patients (43.7%) than in HBeAg-positive (23.8%)[8]. CR, particularly severe CR, may lead to jaundice, prolonged prothrombin time (PT), or eventually liver failure. In our study in Thai patients, two noncirrhotic HBeAg-negative patients developed jaundice (classified as severe CR) 3 mo after NA discontinuation[12]. Jaundice and hepatitis resolved in both patients after retreatment. Clinical decompensation and death following NA discontinuation has been reported in Asian studies; decompensation and fatality were observed in 0%-1.58% and 0%-0.19% in noncirrhotic patients at 1-3 years of follow-up, while there was a limited number of studies in cirrhotic patients[33-35]. The annual incidence of liver decompensation and death were recently reported to be 2.95% and 1%, respectively in cirrhotic patients who stopped NA[33]. Of interest, ENUMERATE study of the patients in the United States reported hepatic decompensation in five of 61 entecavir-treated patients (8.2%) after a median followup of 4 years[36]. Although not from a head-to-head comparison, the data are of concern because liver decompensation in cirrhotic patients who stopped NA therapy seems to be numerically higher than in those who continued treatment. Thus, the current evidence indicates a need for vigilance after NA discontinuation in cirrhotic patients.

HCC risk: There are several well-known benefits of NA treatment in CHB patients[9-11]. Antiviral therapy with NA results in viral suppression, fibrosis improvement, and lower risk of HCC development[37]. Whether patients who stop NA will experience an increased occurrence of HCC in the future than those with continuous treatment is not clear. Nevertheless, to date, HCC development in patients who discontinued NA is not significantly higher than in those who continued NA treatment[33].

GUIDELINE RECOMMENDATIONS

Currently, international practice guidelines for CHB management suggest that patients who had consecutive findings of undetectable HBV DNA for a certain duration can stop NA[9-11]. The expert consensus from the APASL first mentioned treatment discontinuation in 2008, advocating that NA therapy can be stopped in selected patients because of drug resistance concerns in long-term NA treatment[18]. The latest recommendations from international hepatology societies for considering stopping NA therapy are shown in Table 1.

In HBeAg-positive CHB patients, all guidelines allow NA discontinuation in patients who develop HBeAg seroconversion with persistent normal ALT levels and undetectable HBV DNA following consolidation therapy after e-seroconversion for at least 12 mo[38] or preferably 3 years in the APASL guidelines[11]. For patients who are HBeAg-negative, the APASL guideline states that NA can be withdrawn in noncirrhotic patients after treatment for at least 2 years, with an undetectable HBV DNA documented on three consecutive visits, 6 mo apart, or until HBsAg loss with or without development of anti-HBs[11]. Likewise, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) allows stopping NA in highly selected patients with 3 years of continuously suppression of HBV DNA in noncirrhotic patients[9]. On the contrary, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend continuing NA treatment indefinitely unless HBsAg loss is achieved[10]. In patients with liver cirrhosis, the APASL recommends that the discontinuation of NA might be considered, but only with close monitoring[11].

HBV RELAPSE AND PREDICTIVE FACTORS

HBV relapse is a common event after NA discontinuation and can be simply categorized into virological relapse (VR) and CR. Most of the studies defined HBV DNA greater than 2000 IU/mL as the definition of VR, and when in combination with an ALT of at least two times the ULN, CR is recognized. A systematic review by Papatheodoridiset al[8], reported VR rates of 51.4% and 38.2% at 1- and 3-year, respectively, after NA discontinuation. The occurrence of VR was higher in HBeAgnegative patients than in HBeAg-positive patients. The rates were 56.3%vs37.5% and 69.9%vs48.5% at 1- and 3-year, respectively. VR commonly occurred when NA was stopped, but VR alone might not have a clinically significant impact. In some patients, VR may be transient, with a spontaneous decline of viral replication resulting from an immune response. In contrast, a CR may require initiation of retreatment, or more importantly lead to severe flare, and hepatic failure. A randomized controlled study by Liemet al[39] reported that half the patients developed CR after NA discontinuation[39]. Consequently, three-quarters of the patients required retreatment. A summary of the studies reporting the occurrence of VR, CR, and HBsAg loss after NA discontinuation is shown in Table 2.

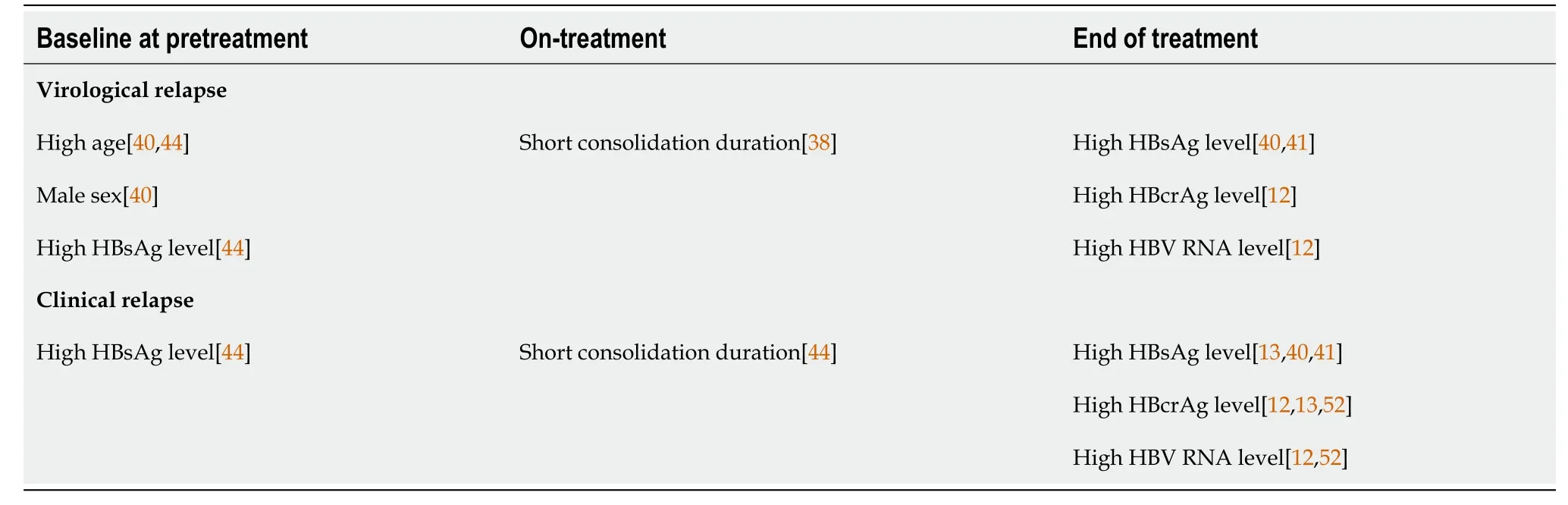

Various baseline and on-treatment factors are associated with VR off-therapy patients. At pretreatment, the baseline characteristics of increasing age and male sex have been associated with an increased relapse rate[40]. During treatment, extension of consolidation treatment duration by more than 1 to 3 years reduces the risk of VR in both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients[38]. For that reason, the international guidelines recommend at least 1 year of consolidation therapy, and preferably 3 years in the APASL guidelines[11], after HBeAg seroconversion before considering NA discontinuation in HBeAg-positive patients. Moreover, the end of treatment (EOT) HBsAg level is highly predictive of HBV relapse, a higher level is correlated with ahigher HBV relapse rate[40,41].

From our point of view, the CR is more clinically important than VR, as it may be followed by liver-related complications. A study in a Thai cohort demonstrated that EOT hepatitis B core-related antigen (HBcrAg) and HBV RNA level were independent risk factors for the subsequent development of CR[12]. A recent meta-analysis including 1573 patients indicated that the higher pretreatment HBsAg levels were associated with shorter consolidation duration and the higher EOT HBsAg levels, especially those > 1000 IU/mL, were independently associated with CR[33]. Many studies attempted to find factors associated with VR and CR, and the reported results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 1 Guidelines for stopping nucleos(t)ide analog therapy

HBsAg CLEARANCE AND PREDICTIVE FACTORS

HBsAg clearance is the desired goal of hepatitis B treatment. Nonetheless, as mentioned above, even if possible, it seldom occurs while on NA treatment, and stopping NA may be a strategy to increase the chance of HBsAg loss. A pivotal Greece study with 33 genotype D, HBeAg-negative patients who stopped ADV, HBsAg loss occurred in 13 of 33 patients (39.4%) after a 6-year follow-up[15]. In addition, the first small randomized controlled trial (RCT) from Germany reported HBsAg clearance in 4 of 21 HBeAg-negative CHB patients after 3-year of off-therapy[42]. However, another RCT conducted by Liemet al[39], in which the majority of the patients were Asian, HBsAg loss occurred in only one patient 1.5 years after NA cessation[39]. Ethnicity and HBV genotype may affect the rate of HBsAg loss.

A large retrospective Taiwanese study that included 691 patients, demonstrated a shorter time to undetectable HBV DNA (especially if assayed less than 12 wk after NA initiation), on-treatment reduction of HBsAg level of > 1 log10IU/mL, and an EOT HBsAg level of < 100 IU/mL were independently associated with an increase in the likelihood of off-therapy HBsAg loss[33]. Furthermore, lower pretreatment ALT and HBV DNA levels, lower EOT HBsAg level, and longer treatment duration predicted HBsAg loss in another study[40]. The predictive factors for HBsAg loss in off-therapy patients are summarized in Table 4.

NOVEL BIOMARKERS TO PREDICT HBV RELAPSE AND HBsAg CLEARANCE

HBsAg quantification

Quantitative serum HBsAg (qHBsAg) has been around in the management of CHB for a while. In untreated patients, serum HBsAg quantification can help to define disease stage, predict spontaneous HBsAg clearance, and predict long-term liver-related complications[43]. As qHBsAg has been used in the clinical practice nowadays, commercial assay kits are widely available. There is increasing evidence of qHBsAg as a marker to aid physicians in deciding whether to discontinue NA. A Taiwanese study by Chenet al[40] found that a cutoff level of < 120 IU/mL predicted HBsAg clearance in HBeAg-negative patients and < 300 IU/mL in HBeAg-positive, respectively[40]. A systematic review by Liuet al[41] indicated that an EOT HBsAg level < 100 IU/mLwas the optimal cutoff[41] to predict low rates of HBV relapse and a high chance of HBsAg loss. A meta-analysis involving 1573 patients found that the same EOT HBsAg level (> 100 IU/mL) was associated with an increased risk of VR and CR, however, it is not predictive of CR in a subgroup of Asian patients[44]. The finding is consistent with our study in Thai patients in which the HBsAg level was not associated with the development of CR. A recent multicenter study by Sonneveldet al[13] found that a cutoff level of < 50 IU/mL was the best for predicting a sustained response and HBsAg loss[13]. In conclusion, HBsAg level is a good predictor of HBsAg loss after NA cessation, but its use as a biomarker to predict CR, especially in Asian patients, is still not clear.

Table 2 Off-therapy virological relapse, clinical relapse, and hepatitis B surface antigen loss in chronic hepatitis B patients

Table 3 Factors predictive of hepatitis B virus relapse

Table 4 Factors predictive of hepatitis B surface antigen clearance

HBcrAg level

Serum HBcrAg has emerged as a novel biomarker in CHB patients. Serum HBcrAg measurement is the combined assay of hepatitis B core antigen, HBeAg, and p22 protein, and it has been shown to be a potential surrogate marker of intrahepatic cccDNA[45,46]. In previous Japanese reports, an increased HBcrAg level was associated with an increase in the rate of off-therapy relapse in NA-treated patients[47]. In addition, a multicenter cohort of Taiwanese patients showed that HBcrAg and HBsAg measured at the time of NA discontinuation were predictive of off-therapy relapse[48]. Moreover, data from CREATE project, a multicenter study including both Asian and Caucasian patients, confirmed the utility of serum HBcrAg. The low cutoff of < 2 log10U/mL was associated with sustained response and HBsAg clearance regardless of HBeAg status and ethnicity[13]. A compilation of the clinical applications of HBcrAg in the cessation of NA is shown in Table 5.

Table 5 Hepatitis B core-related antigen level and clinical application

HBV RNA level

Serum HBV RNA is closely associated with the transcriptional activity of intrahepatic cccDNA and can be quantified by polymerase chain reaction-based techniques[31]. Moreover, this novel marker is potentially valuable in monitoring for relapse after NAdiscontinuation[49]. A study by Wanget al[49] reported that viral rebound occurred in 100% of patients who had detectable HBV RNA at EOT[49]. A recent study in HBeAgpositive patients found that positive serum HBV RNA at EOT was associated with the development of off-therapy CR[50].

The combination of biomarkers

Together, the data suggest that serum qHBsAg, HBcrAg, and HBV RNA, especially at EOT, are predictive of the outcomes following NA cessation. A few studies have explored the usefulness of combining the biomarkers to select the best candidates for stopping NA[12,48,51,52]. A post-hoc analysis from China included 130 CHB patients who discontinued NA and serial followed-up HBV DNA, qHBsAg and HBV RNA[50] found that the combination of negative HBV DNA and HBV RNA at EOT correlated with lower a CR rate and had an excellent 92% negative predictive value (NPV). Another study, combining qHBsAg, and HBcrAg reported that lower qHBsAg, and HBcrAg levels were associated with lower CR and increased HBsAg clearance[48]. Furthermore, a combination of the two biomarkers before stopping NA showed that no patients with negative HBV RNA, and HBcrAg < 4 log10U/mL at EOT developed CR[52]. The result is consistent with that observed in our study of the combination of the three biomarkers,i.e.qHBsAg, HBcrAg, and HBV RNA in the prediction of CR after cessation of NA. We found that HBcrAg of < 3 log10U/mL and HBV RNA of < 2 log10U/mL had 100% NPV for CR[12]. Nonetheless, when combining all three biomarkers, the prediction of CR was not better than that with HBcrAg plus HBV RNA[12].

SCORING SYSTEMS TO PREDICT HBV RELAPSE AND HBsAg CLEARANCE

Apart from using only biomarkers, previous studies illustrated that other clinical and laboratory parameters were significantly associated with post off-treatment outcomes. Therefore, the development of scoring systems utilizing various variables to predict HBV relapse and HBsAg clearance is foreseeable. The first score to predict CR after NA discontinuation is the Japan society of hepatology (JSH) score that consisted of the HBsAg level and HBcrAg level at the time of cessation. The JSH scores are divided into low, moderate, and high-risk groups for HBV relapse after NA cessation[53]. However, this predictive score is not widely used outside the country of origin.

The SCALE-B scoring system was developed using data from 135 Taiwanese CHB patients[48]. The score is comprised of the HBsAg level (S), HBcrAg (C), age (A), ALT (L), and tenofovir (E) for HBV (B) and is calculated as HBsAg (log10IU/mL) + 20 × HBcrAg (log10U/mL) + 2 × age (yr) + ALT (U/L) + 40 for the use of tenofovir. The scores are divided into three strata, low (< 260 points), intermediate (260-320 points), and high (> 320 points) risk of CR. A score of < 260 points was associated with a subsequent HBsAg loss in 27.1% of the patients at 3 years[48]. The SCALE-B score has been validated in a Caucasian population in which it predicted HBsAg clearance, but not relapse[54]. Recently, the CREATE study, which included a large number of Asian as well as Caucasian patients reported that the SCALE-B score predicted CR and HBsAg loss regardless of HBeAg status or ethnicity[13].

IMMUNE SYSTEM EFFECTS AFTER DISCONTINUATION OF ANTIVIRAL AGENTS

T cells contribute to the control of HBV infection by killing infected hepatocytes[55]. However, chronic HBV infection can exhaust immune activity, particularly T cell function[55], as the longer time of HBV infection is associated with the length of exposure to high antigenicity[56]. With NA therapy, T cell function decreases over time. With discontinuation of NA, T cell function may recover with the increase in the number of active T cells and less exhausted phenotypes[57,58].

After the cessation of NA treatment, the HBV DNA usually becomes detectable and often triggers ALT flares that reflect the immune response. Increased numbers of HBVspecific T cells were observed in patients in virological remission after NA discontinuation[59]. A study by Rinkeret al[58] that high function of HBV-specific T cells was observed after NA cessation in patients with subsequent HBsAg loss, especially HBVspecific CD4* T cells[58]. In addition, T cell function increased after programmed death-ligand 1 blockage. More recently, a study by a Spanish group[60] reported that an HBsAg level of ≤ 1000 IU/mL, lower cccDNA transcriptional activity, and a higher HBV-specific T cell response were associated with the development of HBsAg loss.

A new concept of the immune response after NA cessation, beneficial flarevsbad flare is of interest, and was introduced by a Taiwanese group[61]. HBsAg kinetics may be useful in predicting whether patients will require retreatment after CR. Initiation of retreatment is considered in patients who have an increase in HBsAg level before or during ALT flare, which reflects an ineffective immune response. On the other hand, patients in whom a reduction on the HBsAg level was observed before or during ALT flare may not need retreatment, and spontaneous HBsAg clearance may eventually occur[62].

MONITORING /RESTARTING THERAPY AFTER STOPPING ANTIVIRAL AGENT THERAPY

At present, there is no consensus on how to monitor and when to restart NA therapy. Previous studies reported that most HBV relapses occurred within 1 year after the discontinuation of antiviral agents. Most studies recommend careful monitoring, with physical examinations, liver function tests, and serum HBV DNA assays every 1-2 mo for the first 3 mo, every 3 mo for 1 year, and every 6 mo thereafter[12-14,63]. If the patient experiences ALT flare, then close follow-up every week with liver function tests and PT are mandatory for deciding whether prompt retreatment is needed.

Currently, retreatment criteria differ among the studies summarized in Table 6[12,13,39,63]. Most suggested that retreatment should be initiated in patients with an ALT level > 10 times above the ULN regardless of bilirubin level, with an ALT level > 5 times above ULN plus a bilirubin > 1.5-2 mg/dL, persistent of ALT level > 5 times the ULN for 4 wk, or an ALT elevation with either a prolonged PT > 2 sec or a bilirubin level >1.5-2 mg/dL. The retreatment strategy is challenging as CR may reflect the immune restoration and reintroduction of NA might alleviate the effect. However, delayed initiation of retreatment can cause severe ALT flare, and eventually liver decompensation. The biomarkers or tools to aid justification of the optimal timing of retreatment are unmet needs.

PERSPECTIVE OF NA DISCONTINUATION IN EASTERN AND WESTERN COUNTRIES

In Asian and Caucasian populations, there are differences in rates of HBsAg clearance and HBV relapse. Caucasians have a higher probability of achieving a functional cure after NA cessation[13]. HBsAg clearance has been observed in 19%-29% of Caucasians at 2 years[42,64] whereas it had been found in only 1.78%/year in Asians. Thisphenomenon might be explained by the difference of HBV genotypes between Asians and Caucasians, and the duration of infectivity. In Asians, the most common genotypes are B and C, in contrast to the Caucasians in which genotype D is more common[65]. Regarding the duration of infection, most Asian CHB patients are infected perinatally, resulting in a longer extent of chronic infection than in Caucasian patients[66]. Therefore, apart from the chance of patients to have drug-free periods, lower long-term side effects and costs, the ultimate benefit of achieving a functional cure after NA cessation is lower in Asians than in Caucasians.

Another discrepancy between East and West is the consideration of stopping NA in cirrhotic patients. The APASL recommends that in highly selected cirrhotic patients, NA discontinuation may be considered according to the stopping criteria and safety results of previous Asian studies[11,33]. On the contrary, the AASLD and EASL do not recommend NA cessation in cirrhotic patients because safety concerns[9,10].

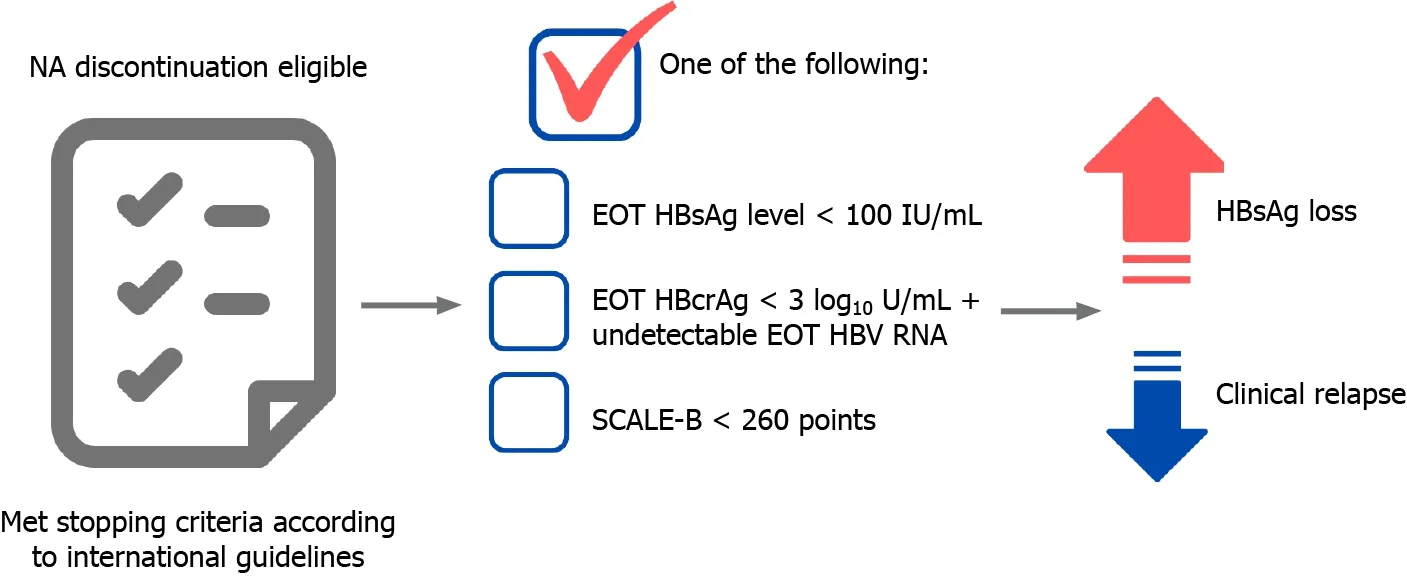

CONCLUSION

From our perspective, the stop strategy is optimal in highly selected noncirrhotic CHB patients. At present, we propose the ideal candidates for NA discontinuation in CHB patients as shown in Figure 2. The major benefit of this strategy is it enhances the chance of achieving a functional cure faster than continuous long-term NA therapy. However, there are some caveats, including severe CR, liver decompensation, or HCC development to be considered. The current unmet needs for NA discontinuation strategy in CHB patients are the better prediction of the patients who are good candidates for stopping, emerging and more widely available noninvasive biomarkers, and the identification of the best timing to consider retreatment initiation, balancing the chance of achieving functional cure and liver decompensation.

Figure 2 Proposed ideal candidates to for stopping the use of antiviral agents in chronic hepatitis B patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Thailand and Thai Association for the Study of the Liver (THASL) for the inspiration and their support for this review. The work is that of the authors only.

World Journal of Hepatology2021年9期

World Journal of Hepatology2021年9期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Addressing hepatic metastases in ovarian cancer: Recent advances in treatment algorithms and the need for a multidisciplinary approach

- Global prevalence of hepatitis B virus serological markers among healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Elevated liver enzymes portends a higher rate of complication and death in SARS-CoV-2

- Development of a risk score to guide targeted hepatitis C testing among human immunodeficiency virus patients in Cambodia

- Probiotics in hepatology: An update

- Drug-induced liver injury and COVID-19: A review for clinical practice