Coronary vasospasm:A narrative review

Jacob Jewulski,Sumesh Khanal,Khagendra Dahal

Jacob Jewulski,Foundational Medical Studies,Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine,Rochester,MI 48309,United States

Sumesh Khanal,Department of Internal Medicine,William Beaumont Hospital,Royal Oak,MI 48073,United States

Khagendra Dahal,Department of Cardiology,CHI Health,Creighton University School of Medicine,Omaha,NE 68118,United States

Abstract Coronary artery vasospasm (CAVS) plays an important role in acute chest pain syndrome caused by transient and partial or complete occlusion of the coronary arteries.Pathophysiology of the disease remains incompletely understood,with autonomic and endothelial dysfunction thought to play an important role.Due to the dynamic nature of the disease,its exact prevalence is not entirely clear but is found to be more prevalent in East Asian and female population.Cigarette smoking remains a prominent risk factor,although CAVS does not follow traditional coronary artery disease risk factors.Many triggers continue to be identified,with recent findings identifying chemotherapeutics,allergens,and inflammatory mediators as playing some role in the exacerbation of CAVS.Provocative testing with direct visualization is currently the gold-standard for diagnosis,but non-invasive tests,including the use of biomarkers,are being increasingly studied to aid in the diagnosis.Treatment of the CAVS is an area of active research.Apart from risk factor modification,calcium channel blockers are currently the first line treatment,with nitrates playing an important adjunct role.High-risk patients with life-threatening complications should be considered for implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD),although timing criteria for escalated therapy require further investigation.The role of pharmaceuticals targeting oxidative stress remains incompletely understood.

Key Words:Coronary artery vasospasm;Vasospastic angina;Prinzmetal angina;Variant angina;Coronary artery disease

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery vasospasm (CAVS) was first described as a “variant” of typical angina pectoris by Dr.Myron Prinzmetal in 1959,hence launching the study of a Prinzmetal(or “variant”) angina,which was subsequently termed vasospastic angina (VSA)[1].Since then,the paradigm surrounding VSA has continued to expand.Symptoms develop upon transient partial or complete occlusion of coronary vessels resulting in a spectrum of clinical manifestations,ranging from stable angina to acute coronary syndrome (ACS),and in some cases sudden cardiac death (SCD)[1-6].The disease process has been identified in patients both with and without coronary artery disease(CAD),affecting both epicardial and microvascular coronary arteries,and having both focal and diffuse involvement[2,4,7].Certainly,traditional risk factors associated with CAD cannot be relied upon as predictors of CAVS,with the exception of cigarette smoking[1].Although a prevailing precedent exists regarding the pathophysiology,diagnostics,and treatment of VSA,previous reviews have identified areas which require further study,especially in cases of refractory disease[8].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

A number of mechanisms have been proposed regarding the mechanism of CAVS,including impairment of parasympathetic activity,coronary vascular and microvascular endothelial dysfunction,enhanced smooth muscle vasoconstriction,chronic inflammation,and oxidative stressors[4,5,7].Recent studies have highlighted rarer causes of CAVS resulting from excessive adrenergic stimulation in cases of catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas[9].

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Approximately 5% to 30% of patients presenting with angina demonstrate normal or non-obstructive coronary arteries when worked up with coronary angiography,despite presenting with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome (ACS)[10-12].Nearly half of these presentations may be attributed to CAVS[5,13],with an increased incidence amongst East Asians,especially Korean and Japanese populations[3,6,13,14].This increased prevalence (in addition to environmental factors) has been attributed to genetic deficiency of variant aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2)genotype amongst these populations15.This correlates with increased toxic aldehyde accumulation,which may from the bases of future targeted treatment strategies in these populations[15].Further studies demonstrate a need for exploring CAVS amongst Japanese adolescents less than 20 years old,whose clinical status matched severity of adults with refractory CAVS[16].

An increased incidence is additionally seen in women,with up to 70% of women showing ACS symptoms without CAD demonstrating findings suggestive of CAVS[17-19].The incidence is particularly high for younger women under the age of 50 years,as well as non-white women[20,21].For this reason,significant consideration should be given to a CAVS workup in patients from these demographics,especially given the tendency for worse outcomes in women compared to men[21].Women with myocardial ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA) should undergo coronary reactivity testing (CRT),which reliably identifies the presence of CAVS[17].

Consideration of CAVS requires high clinical suspicion,and should also be considered in patients with rest angina or patients with anginal symptoms despite unremarkable coronary angiography[6,18].Patients often develop symptoms between midnight and early morning,at times awoken from sleep by symptoms[15].

ETIOLOGY

A number of triggers have been implicated in literature,with the most impactful trigger being cigarette smoking[2,18].Other triggers include psychological stress,cold exposure,hyperventilation,alcohol consumption,stimulants (e.g.,cocaine )[5,22].Given increasing legalization within the United States,marijuana consumption has been considered as a contributor to CAVS exacerbation in a number of case reports[23].

Chemotherapies are other important causes of CAVS.Studies suggest that fluoropyrimidines (including 5-fluorouracil and capecitabine) induce vascular endothelial damage which can cause ischemia secondary to coronary artery vasospasm[24].In such cases,chemotherapy should be halted and standard therapy for CAVS initiated,which should include calcium channel blockers (CCBs) and nitrates[24].Further research is required surrounding cardioprotective agents such as coenzyme complex,glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogues,degradation inhibitors[24],and uridine triacetate[25].Other chemotherapies should be considered if feasible,otherwise a CAD workup should be considered to stratify the patient’s risk for further fluoropyrimidine treatment[26].

Kounis syndrome (KS) is described as the occurrence of ACS in the setting of a mast-cell and platelet mediated hypersensitivity,anaphylactic,anaphylactoid,or allergic reaction[27,28].One pathophysiology of KS includes CAVS,induced by inflammatory mediators[29].Common triggers include antibiotics (especially betalactams[29]) and insect bites,which together account for half of reported cases[27].Recent studies have expanded upon potential triggers,including supplements from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)[27]and injection of cefuroxime[29].

Infectious myocarditis has been implicated in the development of CAVS in patients with otherwise non-obstructive coronary arteries.The underlying mechanism is believed to involve direct inflammatory and infectious interference with endothelial function of the coronary arteries[30].Well documented etiologies include parasitic infections withTreponema cruzi(Chagas disease) and viral infections with parvovirus B19,amongst other causes[30].

DIAGNOSTICS

Studies indicate that CAVS is an underdiagnosed and underreported disease[3,6,14].Correct diagnosis can guide appropriate treatment,which can not only improve patient’s quality of life,but also reduce aforementioned serious risks associated with CAVS,including life-threatening arrhythmias and SCD[14].Current gold standard diagnosis of CAVS utilizes pharmacological provocative testing with high-dose boluses of acetylcholine,ergonovine,or methylergonovineviaintracoronary injection[2,3,5,13,14].The response is then visualized as a coronary vasospasm with transient >90% occlusion of coronary arteries[19],during coronary angiography,orviaabnormalities of ventricular wall motion on echocardiogram[2,3].A standard cardiac workup should initially include standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) during an attack,ambulatory cardiac monitoring,or exercise stress testing to exclude underlying CAD[18].

The Coronary Vasomotion Disorder International Study Group (COVADIS)developed diagnostic criteria for CAVS,which include:(1) Nitrate responsiveness to angina during spontaneous episodes with at least one of rest angina,marked diurnal variation in exercise tolerance,hyperventilation precipitating episodes,or calcium channel blockers (but not β-blockers) suppressing episodes;(2) Transient ischemic changes during spontaneous episodes including at least two contiguous leads with ST segment elevations ≥ 0.1 mV,ST segment depressions ≥ 0.1 mV,or new negative U waves;and (3) Coronary artery spasm visualized either spontaneously or during provocative testing[31].Definitive CAVS is diagnosed if the first and either second or third criteria are fulfilled,which can guide further testing[31].

Although provocative testing is favored in the diagnosis of CAVS and is generally considered safe,the procedure does carry a small chance of serious complications.Recent studies have explored the use of biomarkersviablood test as a possible component in the workup for CAVS.One study explored a number of biomarkers including:(1) Inflammatory markers including C-reactive proteins (CRP),cytokines,lipoprotein (a),and cystatin-C as precipitating factors;(2) Vasoconstrictors including rho-kinase,serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine),and endothelin-1 (ET-1);and (3)Oxidative stressors including thioredoxin and nitrotyrosine[32].

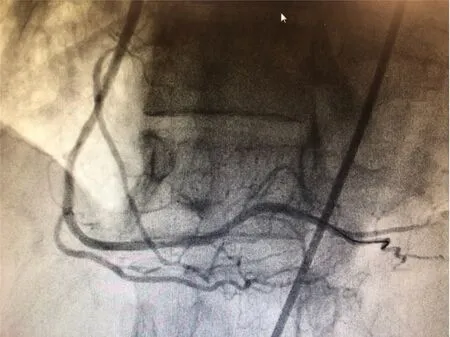

Previous studies have stipulated that increased testing and sensitivity of provocative testing can enhance detection of CAVS worldwide (especially Western countries),but this must be weighed against the risks associated with such testing[14,32].Notably,rapid administration of intracoronary nitrate following provocative testing has resulted in no reported procedure-related deaths[13].Furthermore,recent studies have demonstrated more efficacy and safety with local administration of nitroglycerin to spasming areas through a perforated balloon rather than proximal administration of nitroglycerin,which may further reduce minor risks associated with provocative testing[33].The impact of local nitroglycerin administration on a spasming area of coronary artery can be visualized in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 Coronary angiography demonstrating stenosis of the right coronary artery (arrows).

Figure 2 Coronary angiography demonstrating resolution after intracatheter injection of nitroglycerin.

TREATMENTS

Initial approach to patients with CAVS should include lifestyle modifications,with the most prominent impact coming from smoking cessation[2,18].Once this initial approach has been exhausted and symptoms remain refractory,a number of pharmacological options are available to supplement lifestyle notifications,noted in Table 1.First line pharmacologic treatment should include CCBs,with non-dihydropyridine being preferred but with similar efficacy to dihydropyridine CCBs[2,5].Patients with persistent symptoms may benefit from the addition of long-acting nitrates,which reduce the frequency of anginal symptoms[2].Additionally,sublingual nitrates may be useful for relieving acute episodes of angina[5].Statins and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have shown efficacy in preventing CAVS episodes,and should be considered in all patients presenting with CAVS[2,5,19].One study analyzed the use of sarpogrelate (a serotonin receptor antagonist) in addition to highdose statins for CAVS,but did not find significant improvement of outcomes[34].The use of magnesium and antioxidants (such as vitamin C and E) have demonstrated efficacy in many patients[5].

Table 1 Pharmacologic therapies for coronary artery vasospasm

Patients with refractory disease who do not respond to lifestyle changes and first line pharmacotherapy may consider alpha 1-adrenergic receptor antagonists,rhokinase inhibitors,or nicorandil[2,5,19].Patients with significant atherosclerosis may benefit from percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG),which has shown benefit in patients with concomitant CAVS[5].

Patients who have experienced adverse outcomes of CAVS including lifethreatening ventricular arrythmias or SCD may benefit from an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) in addition to medical therapy[2].Notably,other reversible causes of SCD should be considered before escalating therapy.Although CAVS generally has a favorable prognosis,patients experiencing these adverse outcomes have worse outcomes[35].Predictors of SCD in CAVS patients include advanced age,hypertension,hyperlipidemia,family history of sudden cardiac death,multivessel spasm,and left anterior descending (LAD) artery spasm,and should be considered for escalated therapy[35].Recent studies have also explored the use sympathectomy,which reduced major adverse cardiac events in patients with refractory CAVS when compared to conventional treatment[36].

Beta blockers (BBs),both selective and nonselective forms (especially propranolol),should generally be avoided in patients with CAVS[2,5].Blockage of beta-2 receptors,which prevents smooth muscle relaxation,can exacerbate anginal symptoms.The use of nebivolol,a BB with nitric oxide-releasing effects,has been compared to diltiazem for CAVS – both reduced the effects of CAVS,but diltiazem had greater reduction in symptoms at 12 wk[37].A notable recent exception to this is drug-eluting stentinduced vasospastic angina (DES-VSA),which showed lower 2-year major cardiovascular events (MACE) with BBs compared to CCBs[38].The use of aspirin(especially at high doses) in CAVS remains controversial,and there has been no clear demonstrated benefit of its use in patients with any degree of CAVS[2,5].

FUTURE DIRECTION

Although an understanding of CAVS continues to expand,there remains an ongoing need to better stratify the pathology.The effect of pharmacologic therapy,especially when considering generally avoided medications like BBs,should be tested in larger studies to ensure efficacy[38].Studies have also emphasized the need to explore the use of fractional flow reserve (FFR) in the evaluation of moderate stenosis in the setting of MINOCA,nearly half of whom may have underlying CAVS[13,39].Hearttype fatty acid-binding protein (h-FABP),myocardial performance (Tei) index,and genetic testing have been identified as potentially useful methods for tracking the development of CAVS in patients taking fluoropyrimidines[24,25].Further studies should explore the timing of ICD implantation in high-risk patients with CAVS who would benefit from such therapy[3,35].Future studies should consider populations in Western countries,where CAVS is generally underdiagnosed and undertreated[32].

CONCLUSION

CAVS is an important but underrecognized disease that can result in significant clinical symptoms and/or life-threatening complications.Its prevalence is decreasing due to decreasing prevalence of smoking,increasing use of the medications like calcium channel blockers,statins,and increasing use of non-invasive testing for CAD.It is important to consider CAVS in the differential of anginal chest pain in patients with non-obstructive CAD and treat it appropriately.

World Journal of Cardiology2021年9期

World Journal of Cardiology2021年9期

- World Journal of Cardiology的其它文章

- Quantifying tissue perfusion after peripheral endovascular procedures:Novel tissue perfusion endpoints to improve outcomes

- Exercise-mediated adaptations in vascular function and structure:Beneficial effects in coronary artery disease

- Stent visualization methods to guide percutaneous coronary interventions and assess long-term patency

- Interpersonal violence:Serious sequelae for heart disease in women

- Coronary artery aneurysm:A review

- Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors:New horizon of the heart failure pharmacotherapy