Possible implications of dysregulated nicotinic acetylcholine receptor diffusion and nanocluster formation in myasthenia gravis

Abstract Myasthenia gravis is a rare and invalidating disease affecting the neuromuscular junction of voluntary muscles. The classical form of this autoimmune disease is characterized by the presence of antibodies against the most abundant protein in the neuromuscular junction,the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Other variants of the disease involve autoimmune attack of non-receptor scaffolding proteins or enzymes essential for building or maintaining the integrity of this peripheral synapse. This review summarizes the participation of the above proteins in building the neuromuscular junction and the destruction of this cholinergic synapse by autoimmune aggression in myasthenia gravis. The review also covers the application of a powerful biophysical technique, superresolution optical microscopy, to image the nicotinic receptor in live cells and follow its motional dynamics.The hypothesis is entertained that anomalous nanocluster formation by antibody crosslinking may lead to accelerated endocytic internalization and elevated turnover of the receptor, as observed in myasthenia gravis.

Key Words: agrin; autoimmune diseases; muscle end-plate; muscle specific kinase; MuSK;myasthenia gravis; nanoscopy; neuromuscular junction; nicotinic acetylcholine receptor;rapsyn; superresolution microscopy

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease affecting the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) of voluntary muscles. The NMJ,also known as muscle end-plate, is a peripheral nervous system synapse activated by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.Most cases of MG involve loss of the most abundant protein in the NMJ, the receptor for this neurotransmitter, i.e. the muscle-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR). A predominant clinical manifestation of the MG disorder is fatigability associated with fluctuating muscle weakness,involving predominantly ocular, limb, and respiratory muscles(Burke et al., 2004; Sieb, 2014; Verschuuren et al., 2016).Muscle weakness (de Meel et al., 2019) worsens with activity and improves with rest (Behin and Le Panse, 2018) as a consequence of dysfunctional neuromuscular transmission,with diminution of the so-called safety factor (Serra et al.,2012). The latter is in turn largely due to disruption of the postsynaptic apparatus and to a lesser extent perturbation of normal neurotransmitter binding to the receptor owing to the steric hindrance imposed by antibody binding.

The muscle functional defects in some forms of MG show bulbar involvement: difficulties in swallowing, speech,respiration or muscle-driven eye movement (Burke et al.,2004; Barnett et al., 2014).

The nAChR is the paradigm member of the neurotransmitter receptors belonging to the superfamily of pentameric ligandgated ion channels (Zoli et al., 2018), which includes the families of various other neurotransmitter receptors such as γ-aminobutyric acid type A or C receptors, glycine receptors,subtype 3 of the serotonin receptor families and glutamategated chloride channels (Barrantes 2015; Nemecz et al., 2016).The literature for this review was identi fied by searches of the PubMed database in the last two decades up to April 2020.

Formation and Maintenance of the Neuromuscular Junction

The efficient functioning of the NMJ is ensured by the appropriate number of nAChRs and their very high density. To achieve this appropriate number and distribution of receptors confined in the synaptic region, which occupies only ~0.1%of the muscle cell surface, a complex series of processes takes place during ontogenetic development and postnatal life. These processes involve the orchestrated participation of various proteins in two cascades, one transcriptional and the other post-translational (Sanes and Lichtman, 2001). The agrin-Lrp4-muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) signaling cascade is the master player in the establishment and maintenance of the NMJ, with other receptor-anchoring and scaffolding proteins also playing a role (Burden et al., 2018).

Agrin is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan ~200 kDa protein residing in the extracellular matrix, with three laminin-G-like domains and four epidermal growth factor-like domains contained in the carboxy-terminal half of the protein. The laminin-binding motif is responsible for tethering Agrin to the synaptic basal lamina. Agrin has many splice variants in different tissues. Neural agrin is synthesized by neurons and secreted at nerve terminals. One splice variant is Z8, speci fic to motor neurons and released by presynaptic nerve terminals at the end-plate region. It is this isoform that participates actively in nAChR aggregation and clustering at the NMJ,initially identified by McMahan (1990) in theTorpedoelectromotor synapse. nAChR clusters are absent in agrinknockout animals, that are unable to form NMJs (Gautam et al., 1996). The latter studies gave rise to the idea that agrin is a critical organizer of the NMJ. Agrin is also involved in interneuronal synaptogenesis, e.g., in synapse formation between cholinergic preganglionic axons and sympathetic neurons in the superior cervical ganglion (Gingras et al., 2002).

MuSK is a tyrosine kinase essential for the formation and maintenance of the NMJ. The role played by phosphorylation in synaptic plasticity (Swope et al., 1992) together with the observation that phosphotyrosine staining in muscle fibers was concentrated at the NMJ led Swope and Huganir(1993) to identify this new kinase inTorpedoelectrocytes. As with agrin-null mice (Gautam et al., 1996), MuSK-/-mutant mice form neither nAChR clusters nor NMJs (DeChiara et al., 1997) and die at birth of respiratory failure, mimicking one of the outcomes of severe forms of MG in humans.Phosphorylation of a tyrosine amino acid residue in the MuSK juxtamembrane region requires recruitment of an adapter protein, downstream of kinase-7 (Dok-7), promoting recruitment of two further adapters, Crk and Crk-L, to two tyrosine phosphorylated motifs in the carboxy-terminal region of Dok-7 (Bergamin et al., 2010). Stimulation of MuSK by agrin activates two small GTPases, Rac and Rho, which participate in the formation of nAChR micro- and macroclusters in cultured myotubes (Weston et al., 2003). An additional kinase, Cdc42,intervenes in the agrin-mediated nAChR clustering together with Rac (Weston et al., 2000).

Agrin does not establish direct contact with MuSK; this intermediary role is played by a protein called low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (Lrp4, a single-pass transmembrane protein; Koneczny et al., 2013). Lrp4 is the receptor for agrin and is expressed specifically in myotubes(Kim et al., 2008). It binds to neuronal agrin (Weatherbee et al., 2006), thus integrating the agrin-Lrp4-MuSK signaling cascade involved in nAChR clustering (Zhang et al., 2008).Lrp4 mutant mice die at birth due to respiratory failure(Weatherbee et al., 2006). Lrp4 is also critical for NMJ maintenance (Barik et al., 2014) and plays a role in the central nervous system, where the cascade consists of the agrin-Lrp4-Ror2 signaling system, regulating adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus (Zhang et al., 2019).

Rapsyn is another protein that plays a key role in NMJ development and nAChR clustering and stabilization at the synapse (Noakes et al., 1993). Originally termed 43K protein(Sealock, 1982), rapsyn is a peripheral, cytoplasmic membrane protein whose main role is to act as a scaffold for the nAChR protein. Rapsyn is one of the three proteins known to interact with the nAChR directly, as do adenomatous coli polyposis protein (Farias et al., 2007) and src-family tyrosine protein kinases like Fyn, Fyk, and Src, which are activated by and form a complex with rapsyn (Mohamed and Swope, 1999). Rapsyn is a substrate of these kinases, which phosphorylate the β and δ subunits of the nAChR molecule and are involved in the anchoring of the nAChR to the cytoskeleton (Mohamed and Swope, 1999). Coupling between MuSK and the src-family kinasesin vivois mediated by a phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interaction. Src and Fyn phosphorylate MuSK (Mohamed et al., 2001).

Recently a protein called microtubule actin crosslinking factor 1 (MACF1), a scaffolding protein with binding sites for microtubules and actin, was found to be concentrated at the NMJ. MACF1 binds rapsyn and serves as a synaptic organizer for the microtubule-associated proteins EB1 and MAP1b, and the actin-associated protein, vinculin. MACF1 plays an important role in maintaining synaptic differentiation and efficient synaptic transmission in mice (Oury et al.,2019). Actin and actin-associated proteins involved in F-actin polymerization, such as cortactin and an Arp2/3 complex, are enriched at nAChR clusters in cultured muscle cells (Weston et al., 2007) and are activated by MuSK. The precise mechanisms involved remain poorly understood.

The Cascade in Action

The agrin-Lrp4-MuSK cascade is initiated by nerve-released(neuronal) agrin binding to Lrp4 to form an heterodimer, and subsequently a tetramer composed of two heterodimers (Zong et al., 2012). This tetrameric species is necessary for the next step, the activation of MuSK (Moore et al., 2001; Wang et al.,2006), which in turn recruits Dok-7, the adaptor protein located at the cytoplasmic compartment of the postsynaptic cell.

Dok-7 is a cytoplasmic protein selectively expressed in skeletal and heart muscle that binds a tyrosine phosphorylated site in MuSK and acts downstream of the latter. Mice lacking this protein are not able to form nAChR clusters or NMJs(Okada et al., 2006). Dok-7 is also involved in activating MuSK, playing the role of a ligand that stabilizes and induces MuSK tyrosine phosphorylation. MuSK activation induces the aggregation of nAChR molecules at the end-plate region.Lrp4 is also concentrated and anchored in the postsynaptic membrane as a consequence of MuSK signaling, and acts as a retrograde signal for presynaptic differentiation (Yumoto et al.,2012). Rapsyn, also located in the postsynaptic cytoplasmic compartments, anchors the nAChR via the intracytoplasmic domain of the latter.

The post-natal, developing vertebrate neuromuscular synapse resulting from this complex architectural construction is still immature. Oval shaped, these “plaques” do not form a tightlypacked nAChR continuum but exhibit nAChR-poor areas(“perforations”) containing, surprisingly, proteins typically present in podosomes (Proszynski et al., 2009). Since these podosomes are located underneath nAChR clusters that subsequently become perforated, these authors speculated that the podosomes are involved in remodeling the nAChR clusters as the synapse develops. When podosomes disappear,nAChRs diffuse to these ghost areas. Once formed, the neuromuscular synapse matures over a 3-week post-natal period, during which its size increases between 4- to 5-fold,and the oval shape plaque-like aggregate of nAChRs is sculpted to the typical pretzel-shaped structure with a high density of nAChRs characteristic of the mature NMJ. This is by no means a static structure; nAChRs as well as other molecular constituents of the synapse are continuously being removed and reinserted in the mature synapse, with characteristic lifetimes.

Pathophysiology of the Neuromuscular Junction in Myasthenia

Let us first focus on “classical” MG, the one generated by autoantibodies against the nAChR. Patients with this form of the disease present antibodies in ~85% of cases, although antibody titers do not necessarily correlate with the severity of the disease (Vincent and Newsom-Davis, 1985; Aurangzeb et al., 2009).

The pathophysiology of autoantibody-mediated loss of receptors in the classical anti-nAChR form of MG involves a)blockage of neuromuscular transmission by autoantibody binding to the nAChR; b) enhanced endocytosis; endocytic internalization of the nAChR-autoantibody crosslinked complex and subsequent lysosomal degradation (Borroni et al., 2007;Kumari et al., 2008); c) complement-induced destruction of the NMJ; d) “functional” loss of nAChRs. Let us dissect these various steps.

a) Blockage of neuromuscular transmission by anti-nAChR autoantibody binding occurs at a characteristic site called the main immunogenic region, constituted by a loop of amino acids 66-76 on the α1 receptor subunit (Tzartos et al.,1988). IgG antibodies of the IgG1 and IgG1-3 subclass are characteristically associated with classical anti-nAChR MG.They can activate the complement system, in contrast to the IgG4 subclass. These antibodies, therefore, constitute the first link in the chain of events leading to C3 activation and cleavage of the downstream components in the complement cascade.

b) Enhanced endocytic internalization of the nAChR-autoantibody crosslinked complex and subsequent lysosomal degradation (Borroni et al., 2007; Kumari et al., 2008). The exact cause of this phenomenon is not known. A multiplicity of factors may contribute to this process; we have found for instance that cholesterol depletion from the cell surface can significantly accelerate receptor internalization and even change the endocytic route (Borroni et al., 2007; Borroni and Barrantes, 2011).

c) Complement-induced destruction of the end-plate folds by the formation and deposit of the membrane attack complex,initially leading to partial loss of the postsynaptic folds (Burke et al., 2004) and ultimately to total destruction of the NMJ(Verschuuren et al., 1992). In “classical” MG, autoantibodies to the nAChR bind to the postsynaptic receptors and activate the canonical complement pathway, leading to the formation of the membrane attack complex and the resulting destruction of the NMJ (Verschuuren et al., 2016; Paz and Barrantes 2019). Under physiological conditions, the complement is an important component of the immune system, playing a key role in innate and antibody-mediated immunity. The complement is tightly regulated in its pro- and anti-inflammatory effects,but disruption of this equilibrium can provoke tissue damage in autoimmune diseases like MG or rheumatoid arthritis(Holers and Banda, 2018); under such pathological conditions,activation and ampli fication of the complement system results in the formation of membrane attack complexes involving lipophilic proteins that damage cell membranes (Howard,2018).

d) In contrast to the actual disappearance of nAChRs by the autoimmune attack on the NMJ, “functional” loss of receptors implies interference with the binding of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine to the agonist recognition sites on the nAChR by the anti-nAChR antibodies. This is so because the agonist binding sites are located at the interface between each α1 subunit and a non-α1 subunit, relatively close to the main immunogenic region on the nAChR α1 receptor subunit(Tzartos et al., 1988; Luo et al., 2009). Human IgG antibodies comprise four classes (1-4).Anti-MuSK autoimmune MG is the second most frequent(~6%) form of the disease, mediated by autoantibodies against the muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) (Morsch et al., 2012; Rivner et al., 2018). The anti-MuSK form of the disease is often severe when there is bulbar involvement but milder in non-bulbar variants (Verschuuren et al., 2013;Rivner et al., 2018). The sequence of events described for the autoantibody-induced disappearance of nAChR from the end-plate region does not occur in the case of anti-MuSK autoantibodies, which belong to the IgG4 class of immunoglobulins and do not induce activation of the complement system (Leite et al., 2008; Verschuuren et al.,2013). IgG4 autoantibodies cause MG symptoms by a different physiopathological mechanism: they interfere with the interaction between MuSK and Lrp4, thereby inhibiting the phosphorylation of MuSK normally induced by agrin (Huijbers et al., 2019).

Patients lacking both anti-nAChR and anti-MuSK constitute less than 10% of the total and are considered “seronegative MG”cases by currently available diagnostic immunological tests,although their neurological symptomatology and response to treatment are in some cases similar to those of “classical”anti-nAChR MG patients. Variants of MACF1, the protein that links rapsyn to the microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton(Oury et al., 2019), are associated with congenital myasthenia in humans.

The disruption of the agrin-Lrp4-MuSK cascade precludes agrin-induced nAChR clustering at the end-plate region, as is the case e.g., with anti-Lrp4 myasthenia (Shen et al., 2013) or anti-MuSK myasthenia (Koneczny et al., 2013).

Some seronegative MG patients present anti-nAChR antibodies only against aggregated/clustered forms of the receptor (Leite et al., 2008). This observation raises interesting questions as to the role played by the supramolecular organization of the nAChR in the physiopathology of MG: do receptors in the mature synapse need to disaggregate to generate an immune response? Does the distribution of the nAChR play a role in antibody binding? Conversely, does antibody binding change receptor properties?

Interrogation of these issues is strongly aided by visualization of the receptor in its natural environment, the plasma membrane, using biophysical techniques. We initially addressed this subject by imaging cells expressing adult muscle-type nAChR robustly expressed at the cell surface of CHO-K1/A5 cells, a clonal cell line developed in our laboratory (Roccamo et al., 1999), interrogated with stimulated emission depletion superresolution microscopy(Kellner et al., 2007). This study constituted the first description by optical microscopy beyond the diffraction limit of a neurotransmitter receptor distribution. nAChR aggregates of nanoscopic dimensions (“nanoclusters” of 70-90 nm in diameter) could be directly imaged by stimulated emission depletion superresolution microscopy.

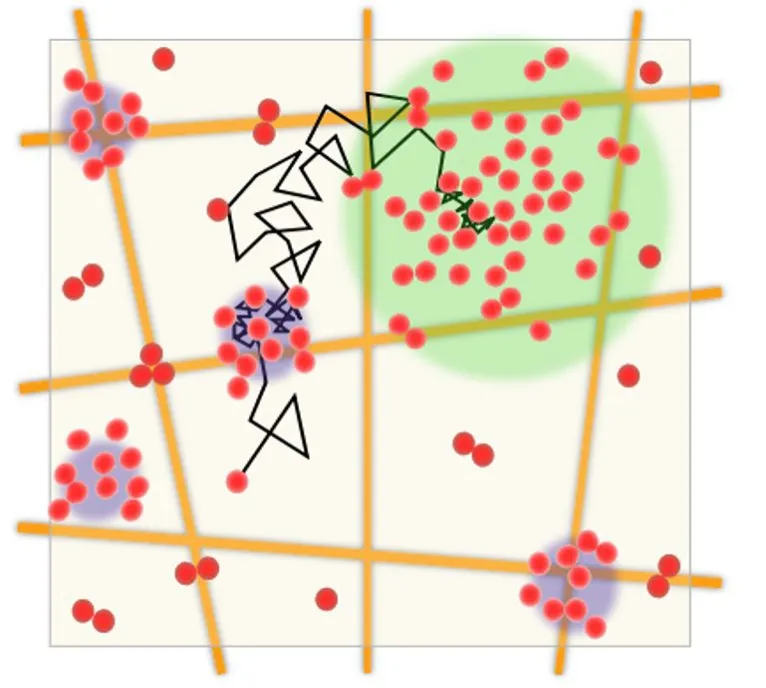

More recently, using stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy, a form of single-molecule localization superresolution microscopy, we could go beyond the static visualization of nAChR nanoclusters. In combination with single-molecule tracking techniques, we were able to follow the motional properties of individual nAChRs labeled with fluorescent α-bungarotoxin (Mosqueira et al., 2018) and compare these motional regimes with those of mAb35-labeled receptors. We selected mAb35, one of the monoclonal antibodies produced by Lindstrom and colleagues (Tzartos et al., 1981) to induce MG experimentally in an animal model of the disease (Tzartos and Lindstrom, 1980). This antibody competes with ~65% of human antibodies found in MG patients (Lindstrom et al., 1982). The behavior of mAb35 is thus presumed to resemble that of the pathogenic autoantibodies found in the human disease.In vitro, MG antibodies have been shown to bind divalently to the nAChR, presumably via the two α-subunits of adjacent receptor monomers and thus crosslink receptors (Paz and Barrantes, 2019). Indeed, we were able to experimentally observe that antibody tagging modi fied the translational diffusion of the nAChR (Mosqueira et al.,2020): diffusion of the fluorescent antibody-labeled receptor differed from the diffusion of the receptor labeled with fluorescent α-bungarotoxin (Mosqueira et al., 2018). The most obvious explanation is that upon antibody (multivalent ligand)binding, antibody-induced crosslinking affects the translational motion of the receptor macromolecule, which spends longer periods in a confined state. The size of the dynamic nAChR nanoclusters also differed between toxin- and antibody-labeled receptors (Figure 1).

Figure 1 | Schematic diagram showing the diffusion of an nAChR molecule in the plane of the membrane, as followed with the stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy single-molecule localization superresolution microscopy technique.

We can speculate that these biophysical observations bear relevance to two phenomena: 1) the single molecule to nanocluster transition that occurs at embryonic stages along the ontogenetic development of the NMJ (Sanes and Lichtman, 2001) and 2) nAChR-antibody interactions in the autoimmune disease MG. Early studies showed that myasthenic antibodies crosslinking nAChR augment the internalization of the receptor (Drachman et al., 1978).We have shown that mAb35 accelerates the endocytic internalization of nAChRs in the CHO-K1/A5 cell line and in C2C12 developing myotubes (Kumari et al., 2008), which, as discussed above, is one of the physiopathological hallmarks of the autoantibody-mediated nAChR disappearance from the NMJ (Fumagalli et al., 1982).

Challenges remain ahead in the field of MG, mostly in relation to the need to develop more sensitive diagnostic tools for the unambiguous identification of MG patients, particularly of seronegative patients, and above all, the development of new therapeutic tools for the treatment of this rare and invalidating disease (Fugger et al., 2020; Lazaridis and Tzartos 2020).

Author contributions:The author wrote the manuscript independently and approved the final manuscript.

Con flicts of interest:The author declares no con flicts of interest.

Financial support:None.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by the author before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Role of apoptosis-inducing factor in perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury

- Dysfunctional glia: contributors to neurodegenerative disorders

- In flammation/bioenergetics-associated neurodegenerative pathologies and concomitant diseases: a role of mitochondria targeted catalase and xanthophylls

- Potential therapeutic effects of polyphenols in Parkinson’s disease: in vivo and in vitro pre-clinical studies

- Hydrogel-based local drug delivery strategies for spinal cord repair

- Altered physiology of gastrointestinal vagal afferents following neurotrauma