Sacral chondroblastoma — a rare location, a rare pathology: A case report and review of literature

Bo-Wen Zheng, Hua-Qing Niu, Xiao-Bin Wang, Jing Li

Bo-Wen Zheng, Xiao-Bin Wang, Jing Li, Department of Spine Surgery, The Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410011, Hunan Province, China

Hua-Qing Niu, Department of Orthopedics Surgery, General Hospital of the Central Theater Command, Wuhan 430061, Hubei Province, China

Abstract BACKGROUND Chondroblastoma (CB) is an intermediate tumor of cartilage origin. CB involving the sacrum is a very rare pathology.CASE SUMMARY A 17-year-old male with sacral CB was diagnosed as CB during the first surgery,and 18 mo later, the tumor recurred and a second surgery was performed with the same pathology result of CB.CONCLUSION We recommend complete removal of the tumor in a timely manner, provided that surgical conditions are met. At the same time, other diseases should be carefully differentiated in terms of imaging or pathological features so as to avoid erroneous diagnostic conclusions.

Key Words: Sacrum; Chondroblastoma; Spine; Pathology; Immunohistochemistry; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Chondroblastoma (CB) is a rare bone tumor of cartilage origin. Among all primary bone tumors, its incidence is 1%-1.4%[1]. The 80% of CBs occur in the epiphysis of the long bones, but CB that occurs in the spine is very rare, accounting for only 1.4% of all CB patients[2]. At present, the treatment of CB mainly relies on complete resection of the tumor, and traditional chemotherapy is often ineffective for CB patients, while radiotherapy can even cause malignant transformation of the disease[3]. Therefore,given our poor understanding of CB, the treatment and prognosis of patients with CB are not optimistic, which seriously affects their long-term quality of life and survival.

To date, only 48 cases of spinal CB have been retrieved from the English literature,and sacral CB is even rarer compared to cervical CB, which occurs less frequently than lumbar and thoracic CB[4]. Up to now, there has been only one case of sacral CB patients reported in the literature[5]. Therefore, in order to report this rare case of both location and pathology, we will present and discuss a 17-year-old male with sacral CB.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 17-year-old male patient, who was admitted to our hospital in September 2018,initially underwent magnetic resonance images (MRI) at a local hospital due to discomfort and pain in the sacrum after strenuous exercise, which concluded sacral occupancy. In addition, the patient did not have symptoms of poor bowel control or weight loss.

History of past illness

The patient has no history of past illness.

Personal and family history

The patient has no special personal and family history.

Physical examination

On admission, the patient's temperature and blood pressure were normal. Physical examination showed tenderness in the sacrococcygeal vertebrae, but sensory and motor functions of the extremities were normal. All were normal except for bilateral kyphoscopic signs (+). Head, neck and cardiac examination were normal. No rash or lymph node enlargement was noted. Abdominal examination was normal with no tenderness or hepatosplenomegaly and normal stools.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory tests: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin and C12 were normal. Human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus tests were negative.

Imaging examinations

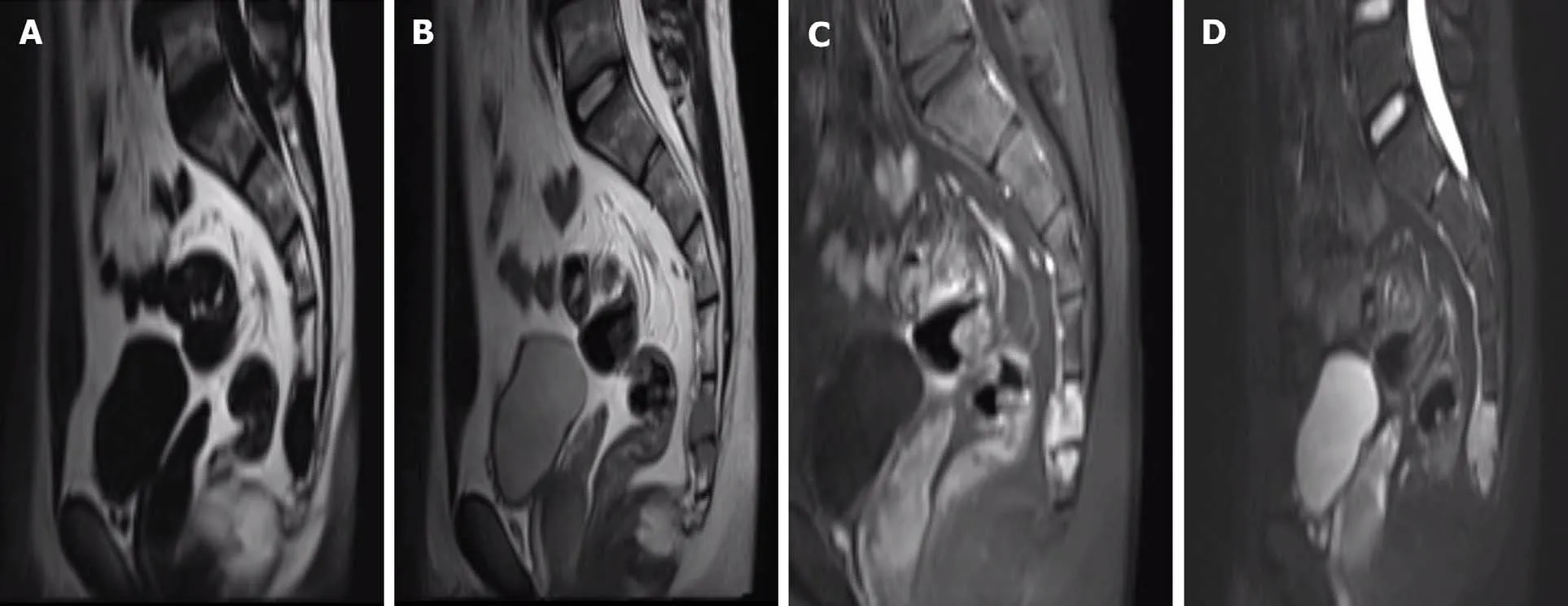

Computed tomography showed an osteolytic lesion with irregular margins and cortical breach (Figure 1); MRI showed that the sacrococcygeal an irregular nodular lesion, with low T1 and high T2 signal, with avid enhancement (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Computed tomography showed shows an osteolytic lesion with irregular margins and cortical breach. A: First preoperative sagittal computed tomography (CT) images (bone window); B: First preoperative sagittal CT images (soft-tissue window); C: First preoperative axial CT images (bone window); D: First preoperative axial CT images (soft-tissue window).

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance images showed that the sacrococcygeal an irregular nodular lesion, with low T1 and high T2 signal, with avid enhancement. A: First preoperative T1-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance (MR) images; B: First preoperative T2-weighted sagittal MR images; C: First preoperative sagittal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images; D: First preoperative sagittal contrast-enhanced T2-weighted MR images.

Pathological findings

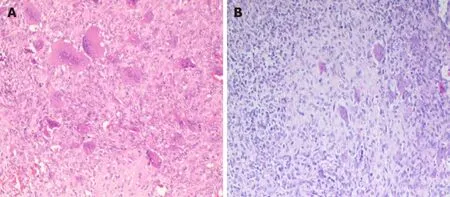

After a comprehensive evaluation, it was decided to perform surgery, and a tumor of about 3 cm × 2 cm in size was successfully removed from the right adnexa of the coccyx, which was poorly demarcated from the surrounding tissue and soft and fishy.Proliferating fibroblasts, multinucleated giant cells and proliferating cartilage tissue were seen in hematoxylin-eosin-stained pathological sections (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemistry showed S100 (+), P53 (5%+), CD34 (++), CD68 (+), Ki67 (40%+), smooth muscle actin (+), mouse double minute 2 homolog (+) and cytokeratin (-). The pathological findings were suggestive of CB.

Figure 3 Hematoxylin-eosin staining. A: First histology of chondroblastoma of hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining: Proliferating fibroblasts, multinucleated giant cells and proliferating cartilage tissue were seen in HE-stained pathological sections; B: Second histology of chondroblastoma of HE staining: Proliferating chondroblasts and cartilage-like matrix with scattered multinucleated giant cells were seen in HE-stained pathological sections.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

CB.

TREATMENT

Postoperatively, the patient recovered and was discharged with regular follow-up.However, 18 mo later, the patient found a recurrence of the tumor at the original surgical site during a routine review and was admitted to our hospital again. The physical examination still did not reveal any meaningful positive signs. MRI showed an interval increase in the lesion with presacral extension, with low T1, high T2 signal,and avid enhancement (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Magnetic resonance images showed an interval increase in the lesion with presacral extension, with low T1, high T2 signal, and avid enhancement. A: Second preoperative T1-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance (MR) images; B: Second preoperative T2-weighted sagittal MR images; C:Second preoperative contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images; D: Second preoperative contrast-enhanced T2-weighted MR images.

The patient underwent surgical treatment again. During the operation, a mass about 7 cm × 6 cm × 5 cm in size on the ventral side of the caudal end of the four sacral vertebrae was removed. The tumor was fish-like, yellowish-brown, rich in blood,irregular in shape, without obvious envelope, with poorly defined border, adhesions to surrounding tissues and rectum, and scar tissue hyperplasia adhesions. Proliferating chondroblasts and cartilage-like matrix with scattered multinucleated giant cells were seen in hematoxylin-eosin-stained pathological sections (Figure 3B).Immunohistochemistry showed cytokeratin (-), vimentin (+), CD68 (+), P63 (+), SATB2(+), S100 (+), smooth muscle actin (+), CD34 (++), CDK4 (-), mouse double minute 2 homolog (+), P53 (45%+) and Ki-67 (60%+). This pathology is consistent with CB, and the patient is still under close follow-up.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

A second surgical treatment was performed and the patient is still under close followup.

DISCUSSION

According to the latest World Health Organization classification, CB is classified as an intermediate tumor that is locally aggressive and rarely metastasizes (< 2%), with a local recurrence rate of up to 38% and a 2% incidence of lung metastases[4]. Spinal CB has a higher recurrence rate and more aggressive tumor growth compared to longbone CB[6,7], and Vialleet al[8] and Giri and Chavan[9] even stated that the local recurrence rate is 100% when CB involves the long bones. In view of the high invasiveness and high recurrence rate of this disease, it is necessary to understand fully this disease.

In demographics, the majority of CB patients are under the age of 50, mainly affecting people in their 20s and 30s, and the prognostic characteristics of CB patients at different sites are very different at different ages[10]. At the same time, there are significantly more male patients than female patients, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1[11,12].

Given the difficulty in distinguishing CB from many diseases and the misjudgment of this patient's first pathological findings, it is important to know the exact pathological features of CB. CB is often distinguished from giant cell tumors,aneurysmal bone cysts (ABC), eosinophilic granulomas, clear cell chondrosarcomas and osteoblastomas. The unique cytologic diagnostic features of CB are chondroblasts,multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells and cartilage-like matrix[1]. Kilpatricket al[13] concluded that in the absence of inflammatory cells, typical chondroblasts are sufficient for the diagnosis of CB, even in the absence of a chondrocyte-like stroma.The key to distinguishing CB from giant cell tumor is that the monocytes of giant cell tumor are spindle-shaped, cohesively arranged in clusters and lack nuclear groove and cartilage-like material in the background[14,15],while chondroblasts are round and often exist alone like a pebble. If the identification is difficult, immunohistochemistry can be used[14,16,17]. In addition, giant cell tumor and CB may be more difficult to differentiate if they are frequently associated with secondary ABC, but mutationspecific H3.3 immunohistochemistry (selectively complementary to next-generation sequencing-based DNA sequencing) and USP6 fluorescencein situhybridization analysis can reliably distinguish cases with difficult morphological identification[18].

The two immunohistochemical results we reported for this patient revealed a high expression of Ki-67 index and CD34, and it has been reported that for Ki-67, as a proliferating cell-related antigen, a Ki-67 index greater than 10% is a high risk factor for bone giant cell tumor recurrence[19]. Therefore, we speculate that the recurrence in this sacral CB patient may be related to the high expression of Ki-67; in addition, CD34 can be used to measure the microvascular density within the tumor mask[20], and it is not difficult to understand that an adequate blood supply is conducive to the recurrent growth of the tumor. This is also suggestive of the highly aggressive nature of this sacral CB, and in addition, we observed that in the pathological findings after recurrence[21,22], P53, which is often present in high-grade bone tumors, had an extensive value-added compared to the first time. This finding is similar to a previous report where an extensive increase of P53 was detected in a patient with pelvic CB who relapsed and died[23].

Also, CB cannot be distinguished on imaging from many common diseases, such as ABC, tuberculous spondylitis, eosinophilic granulomas, osteoblastomas, giant cell tumor, cartilage mucinous, fibromas, chondrosarcomas, osteosarcomas and metastases[7,24,25]. In imaging examinations, CB tends to destroy one side of the vertebral bone,with extensive bone destruction and tissue infiltration[24,26]. The tumor's signal is heterogeneous on MRI T2-weighted and short-TI inversion recovery images, with regions of low signal intensity corresponding to solid components (calcification); nonosteoid tumor matrix and cartilage-like elements are associated with regions of high signal intensity[25,27]. There was significant enhancement of the tumor, and the thickness of the tumor border was usually less than 1 mm, which was also similar to the imaging features of the patient we reported. In addition, whole-body positron emission computed tomography examination can help determine the presence of distant metastases.

Currently, in the treatment of patients with CB of long bones, thorough tumor curettage with high-speed grinding drills, bone cement filling or radiofrequency ablation can lead to a good long-term prognosis and preserve as much normal function of the limb as possible[28,29]. In addition to chemical (phenol), electrocautery or cryosurgery can be used as adjuvant treatment for CB patients[30]. Whereas surgery is the only effective treatment for cranial CB, the probability of recurrence is greatly increased if residual lesions are present after surgery in patients with cranial CB[31].Spinal CB has a higher recurrence rate compared to CB occurring in the long bones,and the growth of spinal CB is more aggressive[6,7]. Vialleet al[8] stated that the local recurrence rate is 24% to 100% when spinal CB involves the long bones, and for spine CB, a simple resection cannot achieve a good therapeutic effect[4]. In addition, most of the literature recommends complete resection of the vertebral body, complete nerve decompression and simultaneous reconstruction of spinal stability[2,7,10,32].However, extensive resection may be difficult to perform in clinical practice due to the complex anatomy and infiltration of vital internal organs and neurovascular structures by tumor tissue, which can lead to an increased rate of patient recurrence. A singlecenter study of 13 spinal CBs found that patients with curettage resection had a 100%patient recurrence rate, whereas none of the patients with totalen blocspondylectomy resection recurred during follow-up[4]. Similarly, our patient experienced recurrence in less than 2 years after curettage resection. This also reflects the importance of performing complete resection of the spinal CB.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we report a case of a rare tumor occurring in a rare location, sacral CB.We recommend complete removal of the tumor in a timely manner, provided that surgical conditions are met. At the same time, other diseases should be carefully differentiated in terms of imaging or pathological features so as to avoid erroneous diagnostic conclusions. However, due to the rarity of this disease, a large sample of cases will be needed to explore further this disease in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Jiang Y and Dr. She XL from Department of Pathology, The Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University for pathological analysis of the study.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2021年20期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2021年20期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Corrigendum to “Probiotic mixture VSL#3: An overview of basic and clinical studies in chronic diseases”

- Role of gastrointestinal system on transmission and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2

- COVID-19: Considerations about immune suppression and biologicals at the time of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic

- Histopathology and immunophenotyping of late onset cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in elderly patients: Three case reports

- Multidisciplinary team therapy for left giant adrenocortical carcinoma: A case report

- Hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic cerebral proliferative angiopathy: A case report