Type 2 diabetes mellitus increases liver transplant-free mortality in patients with cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Zi-Jin Liu, Yi-Jie Yan, Hong-Lei Weng, Hui-Guo Ding

Zi-Jin Liu, Yi-Jie Yan, Hui-Guo Ding, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Beijing You’an Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University, Beijing 100069, China

Hong-Lei Weng, Department of Medicine II, Section Molecular Hepatology, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Mannheim 68167, Germany

Abstract BACKGROUND The impact of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) on the prognosis and complications of liver cirrhosis is not fully clarified.AIM To clarify the mortality and related risk factors as well as complications in cirrhotic patients with T2DM.METHODS We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library from their inception to December 1, 2020 for cohort studies comparing liver transplant-free mortality,hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP),variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) in cirrhotic patients with vs without T2DM. Odds ratios (ORs) were combined by using fixed-effects or random-effects models with RevMan software.RESULTS The database search generated a total of 17 cohort studies that met the inclusion criteria. Among these studies, eight reported the risk of mortality, and eight reported the risk of HCC. Three studies provided SBP rates, and two documented ascites rates. Four articles focused on HE rates, and three focused on variceal bleeding rates. Meta-analysis indicated that T2DM was significantly associated with an increased risk of liver transplant-free mortality [OR: 1.28, 95% confidence intervals (CI): 1.16-1.41, P < 0.0001] and HCC incidence (OR: 1.82, 95%CI: 1.32-2.51, P = 0.003). The risk of SBP was not significantly increased (OR: 1.16 95%CI:0.86-1.57, P = 0.34). Additionally, T2DM did not significantly increase HE (OR:1.31 95%CI: 0.97-1.77, P = 0.08), ascites (OR: 1.11 95%CI: 0.84-1.46, P = 0.46), and variceal bleeding (OR: 1.34, 95%CI: 0.99-1.82, P = 0.06).CONCLUSION The findings suggest that cirrhotic patients with T2DM have a poor prognosis and high risk of HCC. T2DM may not be associated with an increased risk of SBP,variceal bleeding, ascites, or HE in cirrhotic patients with T2DM.Key Words: Diabetes mellitus; Mortality; Liver cirrhosis; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Metaanalysis

INTRODUCTION

Globally, liver cirrhosis is an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality and is the 14thmost common cause of death[1]. The liver plays a pivotal role in glucose homeostasis. It stores glycogen in the fed state and produces glucose through glycogenolysis. Former researchers found that 20%-30% of overt type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) cases and 60%-80% of impaired glucose tolerance cases occur in liver cirrhotic patients[2,3]. Whether the presence of T2DM in patients with cirrhosis can increase mortality is also controversial. Some studies proved that cirrhosis patients with T2DM have higher mortality than patients without[4,5],while other studies found opposite results[6,7]. T2DM may increase the risk of infection; however, some research found no difference in the spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) rate between cirrhosis patients with and without T2DM[8].

We therefore conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the association between T2DM and mortality as well as its complications in patients with liver cirrhosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines[9]. Our primary endpoints were defined as liver transplant-free mortality and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence. Secondary endpoints included ascites, SBP, variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy (HE). All these outcomes were defined by the authors of the primary studies. Two investigators (Liu ZJ and Yan YJ) independently searched PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (up to December 1, 2020) using the following MeSH and their free terms: “Liver cirrhosis”AND “type 2 diabetes mellitus” AND (“mortality” OR “spontaneous bacterial peritonitis” OR “ascites” OR “variceal bleeding” OR “hepatic encephalopathies” OR“hepatocellular carcinoma”). The search was further reviewed systematically, and the literature was limited by the language of English.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if: (1) They were retrospective or prospective cohort studies comparing mortality and complications of liver cirrhosis patients who hadvsdid not have T2DM; (2) They were published in full text in a peer-reviewed journal; and (3)They involved 50 or more adult patients and the follow-up period was longer than 6 mo. Studies were excluded if: (1) They were animal or basic studies; (2) They were meta-analyses or reviews; (3) They were cross-sectional studies or case-control studies;(4) They were case reports; (5) They involved patients undergoing liver transplant surgery; (6) They were conference abstracts; or (7) They were not published in English.

Data extraction

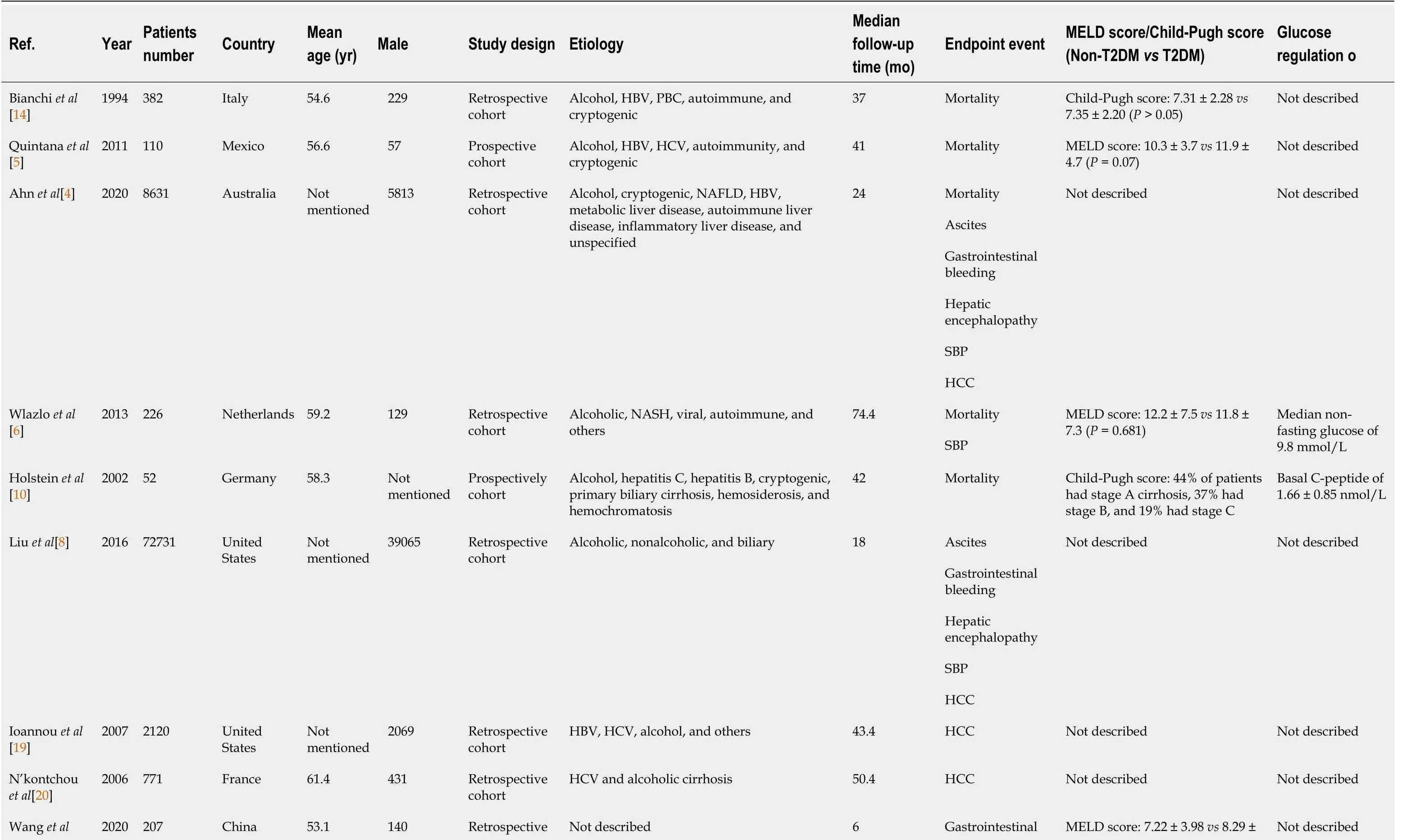

Two investigators (Liu ZJ and Yan YJ) independently and separately assessed the trials for eligibility and extracted data. For each individual study, the following study characteristics were collected: First authors’ name, total patients included, year,country, mean age, sex, study design, etiology of the underlying liver diseases, mean follow-up time, endpoint events, liver function, and glucose regulation (T2DMvsnon-T2DM).

Quality assessment

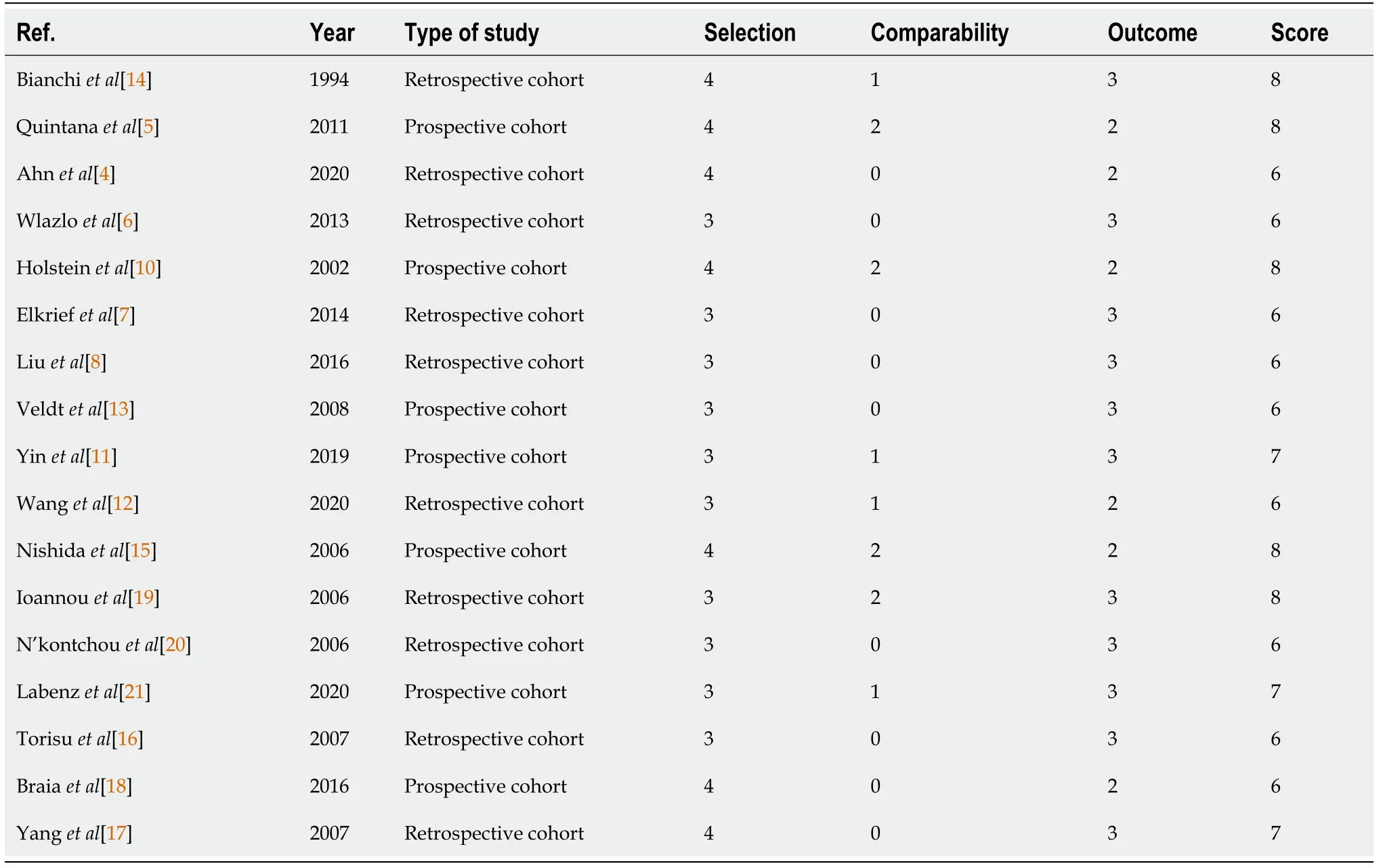

The included cohort studies were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Studies were considered high quality if they received 5 or more points, whereas studies were considered low quality if they received 4 or fewer points.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4 (Cochrane Center, Denmark).Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were used as summary estimates, and analysis was performed using the fixed-effects model or random-effects model if heterogeneity was considered significant. Heterogeneity was measured using theI2statistic. High statistical heterogeneity was defined as greater than 70%, medium heterogeneity was defined as 50%-70%, and low heterogeneity was defined as 0%-50%.The Begg and Egger tests were performed using STATA MP16 withP< 0.05 indicating significant publication bias.

RESULTS

Literature identification

A total of 617 articles were searched from PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials. After removal of duplicates, 439 articles were screened using the title and abstract. Full text was obtained for 50 articles, which were screened for inclusion eligibility in the study. Overall, 17 articles met the criteria for eligibility and were included in the meta-analysis[4-8,10-21]. A Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram showing the study selection process is shown in Figure 1. Eight articles focused on mortality, eight on HCC, two on ascites, three on variceal bleeding, four on HE, three on HCC, and three on SBP. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. The methodologic quality assessment of the included studies is presented in Table 2. All studies were of high quality.

Table 2 Newcastle-Ottawa Scale score

Figure 1 Flow diagram of the research selection process.

Table 1 Characteristics of the studies

HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; PBC: Primary biliary cirrhosis; MELD: Model for End Stage Liver Disease; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; SBP: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis;NASH: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; AIH: Autoimmune hepatitis; T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Primary outcomes

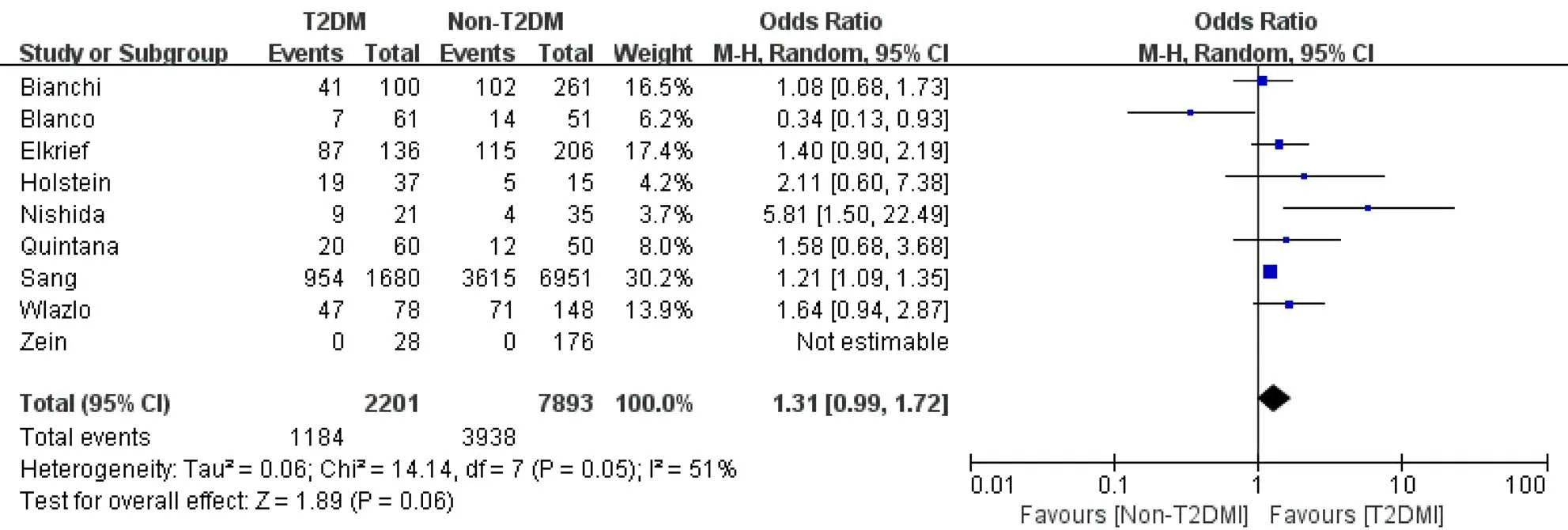

Mortality:Eight studies reported the mortality of cirrhotic patients withvswithout T2DM[4-7,10,14,15,17]. There was low heterogeneity across studies, so a fixed-effects model was used. Patients with T2DM were associated with a significantly higher liver transplant-free mortality than patients without T2DM (OR: 1.28, 95%CI: 1.16-1.41,P<0.0001) (Figure 2). Begg’s test showed no significant publication bias (P= 0.07), while Egger’s test showed slight publication bias (P= 0.03).

Figure 2 Liver transplant-free mortality of patients with vs without type 2 diabetes mellitus. T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; CI: Confidence interval.

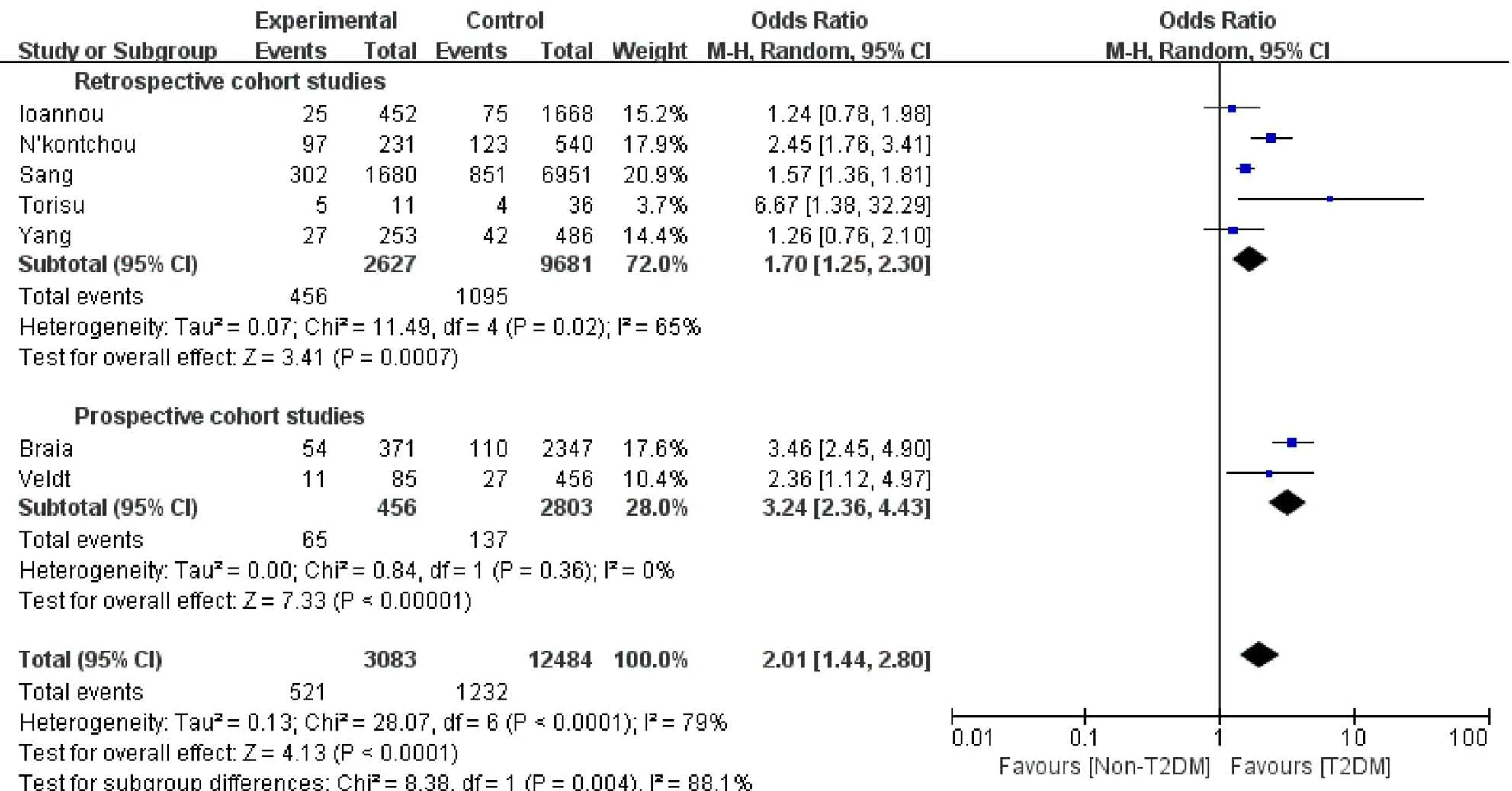

HCC:Eight studies[4,8,11,16-20] assessing the association between T2DM and HCC were enrolled. Compared to the non-T2DM patients, the T2DM patients had a higher incidence of HCC (OR 1.82, 95%CI: 1.32-2.51,P= 0.003,I2= 91%). Sensitivity analysis showed that after removing the study by Liuet al[8], the heterogeneity decreased from 91% to 79%. Subgroup analysis based on the category of the studies was performed to further reduce the heterogeneity among the studies. In the retrospective cohort study subgroup, the OR was 1.7 (95%CI: 1.25- 2.3,P= 0.0007,I2= 65%); however, in the other subgroup, the OR became 3.24 (95%CI: 2.36-4.43,P< 0.0001,I2= 0%) (Figure 3).Publication bias was not detected with a Begg’s test P value of 0.71 and an Egger’s of 0.11.

Figure 3 Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with vs without type 2 diabetes mellitus. T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; CI: Confidence interval.

Secondary outcomes

SBP:Three retrospective studies on SBP were included and indicated that cirrhosis patients with T2DM had the same risk of SBP as non-T2DM patients (OR: 1.16 95%CI:0.86-1.57; Figure 4) with medium heterogeneity[4,6,8]. The sensitivity analysis results showed that Wlazlo et al[6] was the source of the heterogeneity. After removing this study, the heterogeneity decreased to zero (OR: 1.01 95%CI: 0.89-1.54, P = 0.89). The incidence of SBP remained unchanged.

Figure 4 Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with vs without type 2 diabetes mellitus. T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; CI: Confidence interval.

HE:In terms of HE, patients with T2DM did not have a significantly higher rate (OR:1.31 95%CI: 0.97-1.77, P = 0.08, I2=77%)[4,8,11,21]. We found that Yin et al[11] was the source of the heterogeneity through sensitivity analysis. After combining the other studies, the OR became 1.12 (95%CI: 0.9-1.39, P = 0.3, I2=57%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Hepatic encephalopathy in patients with vs without type 2 diabetes mellitus. T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; CI: Confidence interval.

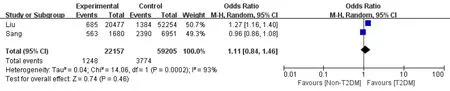

Ascites:Of the two articles[4,8] that reported T2DM and ascites in cirrhosis patients,our meta-analysis identified an OR of 1.11 (95%CI: 0.84-1.46,P= 0.46). Due to the limited study number, subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis were infeasible. As a result, whether T2DM increases the ascites rate of cirrhosis patients remains controversial (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Ascites in patients with vs without type 2 diabetes mellitus. T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; CI: Confidence interval.

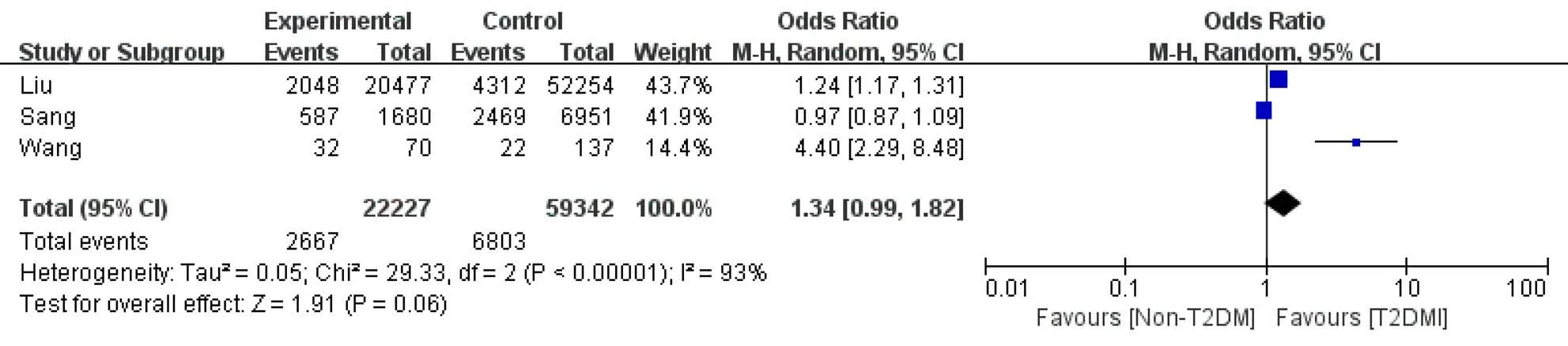

Variceal bleeding:We obtained three studies that focused on variceal bleeding[4,8,12]. They reported an OR of 1.34 (95%CI: 0.99-1.82,P= 0.06,I2=93%). After the sensitivity study or the subgroup study, the heterogeneity was not decreased significantly (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Variceal bleeding in patients with vs without type 2 diabetes mellitus. T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; CI: Confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The results of our meta-analysis showed that T2DM was associated with increased liver transplant-free mortality and HCC rates in patients with cirrhosis. The SBP and HE incidence of T2DMvsnon-T2DM was not significantly different. Other comparisons of complication rates between T2DM and non-T2DM patients could not be made due to the high heterogeneity and low study numbers.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis focused on the mortality of cirrhotic patients with T2DM. Because there was no randomized controlled trial study, we only enrolled high-quality cohort studies in this meta-analysis, which we believe did not reduce the credibility of the results. In terms of publication bias, due to the limited number of studies, Begg’s and Egger’s tests might not accurately reflect publication bias, so the contradictory results should be explained cautiously. There are many theories that could explain why T2DM increases the mortality of cirrhosis. As reported recently, inflammation status was enhanced in T2DM, and various cytokines and proinflammatory factors, such as C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha,interleukin-6, interleukin-1β, interleukin-18, and interferon-gamma, were detected in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue in patients with diabetes[22,23]. Many of these factors stimulate collagen production by stellate cells, resulting in increased production of connective tissue growth factor and extracellular matrix accumulation and ultimately promoting fibrosis and cirrhosis[24]. Moreover, cirrhotic patients with infections were prone to liver failure, hepatorenal syndrome, and high hospital

mortality[25]. In addition, oxidative stress is an upstream event for inflammation, as it induces the activation of monocytes and macrophages and promotes inflammatory responses involved in insulin resistance in T2DM[26]. In the liver, oxidative stress can activate hepatic stellate cells, promote a phenotypic switch, and deposit an excessive amount of extracellular matrix that alters the normal liver architecture and negatively affects liver function. Additionally, oxidative stress can stimulate necrosis and apoptosis of hepatocytes, which can cause liver injury and lead to the progression of end-stage liver disease[27].

As previously reported, our meta-analysis showed that T2DM significantly increased the liver malignancy incidence in liver cirrhotic patients[28,29]. After the sensitivity analysis, we found that Liuet al[8] caused relatively high heterogeneity.This study was a large-number ‘real-world’ study, whose data mainly came from the electrical medical system. Liuet al[8] estimated that the HCC rate in T2DM patients was 5.2%, which was lower than that in other cohort studies. This underestimation was probably caused by missing data and a lack of quality control in the‘real-world’study. The subgroup analysis based on the study category further reduced the heterogeneity to a medium level. Compared to retrospective cohort studies, prospective cohort studies could control the bias as well as missing data and make it closer to reality. As a result, we suspected that the OR of HCC in cirrhotic patients with T2DM was approximately 2-3 times that of their non-T2DM counterparts. T2DM might increase the risk of different cancers, and the mechanisms involve the oxidative stress process and activation of the IGF signaling pathway[30,31]. Hyperglycemia could accelerate the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Plasma membrane peroxidation was initiated by ROS and impaired PI-3-kinase signaling pathways.Hyperglycemia-induced cell damage induces ROS production along with cytokine activation, specifically NF-kB and STAT 3, which have an imperative role in inflammatory responses and altered homeostasis in the liver and cause HCC development and progression[32]. Deregulation of the IGF axis signaling pathway may lead to the development of cancer in several tissue types. IGF-I, a major ligand that is extremely expressed in the liver,may be antitumorigenic in HCC but acts as a substrate for HCC development in liver cirrhosis; thus, decreased IGF-I levels could contribute to hepatocarcinogenesis. HCC development commences with a significant decrease in IGF-I levels and the extent of loss of liver function. A reduced IGF-I level is associated with higher tumor intrusiveness and reduced prognosis[33,34].

To our surprise, our meta-analysis did not find a significantly higher prevalence of SBP in T2DM patients. Theoretically, the low-grade inflammatory state of T2DM, as mentioned above, partly came from endotoxemia produced by intestinal microbiota.This might further cause gut permeability, disruption of tight junction proteins in gut epithelial cells, and bacterial translocation, which finally gave rise to SBP. However,Bajajet al[35] found that although T2DM in the presence of cirrhosis altered the mucosal and stool microbiota, it did not add to the 90-d hospitalization risk or other negative outcomes. Therefore, more research is needed on gut microbiota to determine the relationship between T2DM and SBP. In terms of HE, the present meta-analysis failed to find a clear connection between T2DM and HE. Past research has shown that T2DM can worsen hepatic encephalopathy by increasing glutaminase activity,impairing gut motility, and promoting constipation, intestinal bacterial overgrowth,and bacterial translocation. However, based on the latest guidelines, which kind of HE(minimal or overt HE) that T2DM might lead to is unknown[36]. Because the studies that we enrolled did not define the diagnosis very accurately, future studies should further research this topic. Regarding ascites, some researchers found that perisinusoidal fibrosis, the so-called diabetic hepatosclerosis, most often occurred in subjects with longstanding diabetes and microvascular disease in other organs, especially the kidney, and caused refractory ascites in patients with advanced cirrhosis[37]. Finally,hyperglycemia may aggravate liver function damage and cause hypoalbuminemia,decrease blood coagulation, and finally lead to a series of hemorrhages, including variceal bleeding.

This meta-analysis had some limitations. First, we could only enroll observational studies rather than clinical trials on this topic. Second, the high heterogeneity and low study number disabled us from making quantitative analysis of some secondary outcomes, such as HE, HCC, ascites, and variceal bleeding. Nevertheless, this was the first meta-analysis to research the mortality and major complications of cirrhotic patients with T2DM.

CONCLUSION

T2DM was associated with increased liver transplant-free mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Future studies should focus on the underlying mechanism and its management.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and liver cirrhosis have become the major threats to people’s health globally. However, whether the presence of T2DM in patients with cirrhosis can increase mortality and other liver-related complications is also controversial.

Research motivation

A comprehensive systemic review and meta-analysis can help conclude the relative article results and help doctors to make clinical decisions easily.

Research objectives

The aim of this meta-analysis was to clarify the mortality and related risk factors as well as complications in cirrhotic patients with T2DM.

Research methods

Studies were enrolled following specific criteria. The primary endpoints were defined as liver transplant-free mortality and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence.Secondary endpoints included ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), variceal bleeding, and hepatic encephalopathy (HE). Studies results were combined using RevMan software.

Research results

Meta-analysis indicated that T2DM was significantly associated with an increased risk of liver transplant-free mortality [odds ratios (OR): 1.28, 95% confidence intervals (CI):1.16-1.41,P< 0.0001] and HCC incidence (OR: 1.82, 95%CI: 1.32-2.51,P= 0.003). The risk of SBP was not significantly increased (OR: 1.16, 95%CI: 0.86-1.57,P= 0.34).Additionally, T2DM did not significantly increase HE (OR: 1.31, 95%CI: 0.97-1.77,P=0.08), ascites (OR: 1.11, 95%CI: 0.84-1.46,P= 0.46), and variceal bleeding (OR: 1.34,95%CI: 0.99-1.82,P= 0.06).

Research conclusions

T2DM patients have a poor prognosis and high risk of HCC. T2DM may not be associated with an increased risk of SBP, variceal bleeding, ascites, or HE in cirrhotic patients.

Research perspectives

More attention should be paid to T2DM in liver cirrhosis patients to improve better prognosis of these patients.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2021年20期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2021年20期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Obesity in people with diabetes in COVID-19 times: Important considerations and precautions to be taken

- Revisiting delayed appendectomy in patients with acute appendicitis

- Detection of short stature homeobox 2 and RAS-associated domain family 1 subtype A DNA methylation in interventional pulmonology

- Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer and vascular resections in the era of neoadjuvant therapy

- Esophageal manifestation in patients with scleroderma

- Exploration of transmission chain and prevention of the recurrence of coronavirus disease 2019 in Heilongjiang Province due to inhospital transmission