TAPESTRY OF LIFE AND DEATH

Fiber artist Yue Mingyue uses airy gauze and yarn to explore subjects of great weight, with emotional depth thinly veiled behind ethereal beauty. Yues work is often deeply personal, inspired by childhood memories such as her mothers kidney failure, which left Yue plagued by the fear of death in her family as a young teenager.

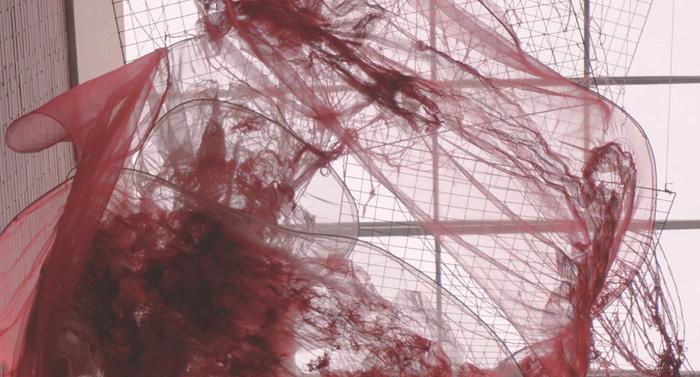

In memory of her mothers hysterectomy, Yue exhibited “Blessed Be the Fruit” at the Tsinghua University Art Museum in 2018, encouraging gallery-goers to wrap themselves up in a concatenation of long crimson fibers that rekindle the safety and warmth of being returned to the womb. She is best known for making installations with black and red gauze, weaving together life and death in a series of centerpieces that present deaths presence in life, and vice versa.

Yue describes her work as something that “may not be in sync” with mainstream Chinese art language. Her art also updates embroidery and textiles, traditionally feminine crafts, in order to explore womens issues in modern China. In her most recent piece, a work of embroidery called “Female Worker Crossing the Rosen Bridge,” she uses symbol from Western medieval tapestry to explore what stays the same for women in rural China in an age of great change.

Why do you see life and death as being linked?

The fact that life and death coexist is something everyone in the world has to recognize repeatedly from the moment theyre born. They might start by recognizing that people around them die, then learn that they themselves can die, and then come to accept it. The last work in my “Death” series, which is a film called On and On, is about an infant—when it was born it was very happy, but one day it realizes its life has a limit. Then it starts to resist death, before going on to accept death. The acceptance of death becomes a part of its life.

One of these processes of acceptance came with the death of your grandfather. Apparently, you had a traditional Chinese funeral for him?

I went back to my hometown and all the relatives were there. First, we had a ceremony for saying goodbye. We went up the mountain together and we brought [models of] houses and luxury goods made of paper—everything from life you wished for him to taking along [to the afterlife]—which we burned to send to him. This was the first time in my life I had ever attended a traditional funeral. I felt the most important thing was that everything was burned, including the body, so fire is a medium that connects two worlds. That really moved me.

Can you tell me about your thought process when trying to go about linking life and death?

“Drama Continuous—Black Flowers” is part of the black gauze series. It was created in the context of a funeral and made for my grandfather. The material was burned with fire to make it scorched and curled at the edges, because I wanted to send it to my grandfather. I felt that all the cloth had to be burned, and only then could he feel it. My red gauze series represented the transition from a series about death to a series about life. One of these is “Blessed Be the Fruit,” which is a very large installation. I wanted to make it resemble a womb the audience could walk into, so that its as if they were returning to the container that is the beginning of life, the place where life began to stir.

Could you explain the process of creating a work of art that viewers could actually walk through and embrace?

[My mothers hysterectomy] made me think of the relationship between women, the uterus, and children, building on previous works Id done on life, death, and now birth. On the other hand, as a woman who has not given birth, I created this work to recognize the greatness of women in the process of giving birth. The name “Blessed Be the Fruit” came from talking with a friend about The Handmaids Tale TV series, and how womens uteruses have been used by society; because it has the ability to nurture life, its been bound with the development of societies around the world. The uterus is a space of love and humanity, rather than just a baby-making machine. So when I made this work, I really wanted to make sure the audience could walk into it. It is only then, when all the threads and gauzes are moving due to the people walking around, that the audience can feel the love and protection of being wrapped in a mothers body and really understand the work.

Aside from “Blessed Be the Fruit,” are there any works youre particularly proud of?

That would be the work I just showed, “Female Worker Crossing the Rosen Bridge.” It was something I made specially for a female-themed exhibition, so the work is about women doing weaving 1,000 years ago while also farming during the busy agricultural seasons. One inspiration was a hand-weaving studio in a small town in Liaoning called Kazuo. The studio is in a village close to the workers homes and they work there when its not the agricultural season, and go back home when they need to help with farm work. My work is about how women across a thousand-year period are still taking on a variety of responsibilities.

The reason I did this piece is because very few people look at the labor that women contributed to agriculture. They might think that weaving is more like womens work, but whether 1,000 years ago or now, women have contributed a lot of labor toward food and farming.

I plan to do more works related to female workers, but I havent entered too many communities of women yet. I havent reached the point where I can really express the desire of these groups of women.

What problems do female workers in China currently face?

One of the big contradictions I want to explore more in my work is when women workers in the workplace face an over-abundance of choices—for example, while working they might think about their desire for a family or having children, and they always think about this more than men have to. But I havent figured out how to explore this.

Have there been any challenges when creating your pieces?

Early in my career, around 2018, I did an LGBT-themed work [at Tsinghua]. It was a rainbow, with gauzes of different colors hung at different heights in front of a transparent screen. The day it was exhibited was Gender Equality Day, so lots of activists had gathered with rainbow flags on campus. The original agreement with the venue was to put on the exhibit for a month, but after showing this work for just one morning, I was suddenly notified to withdraw it in the afternoon. The university felt the exhibit together with the event on campus was unsafe and had too many “uncertainties.”

This work was treated like a talking point, because it came out on a special day and it experienced an inspection. It was blown out of proportion. I feel like this happens to a lot of works that are themed around women; they are made into talking points, but sometimes, the message is only a part of the work, while the work also has aesthetic values that you have to look at. Now often when I work Im thinking about how to create the work itself and create something that is beautiful and still gives a good experience when you remove the thematic elements. This is what Im working hard to achieve in my current career—that even when you remove the message and the labels, the work is still good. – Alex Colville

Born in a small village in Liaoning province in 1996, Yue Mingyue is a fiber artist based in Beijing. She received her Bachelors in design from the Department of Arts and Crafts at Tsinghua University in 2018, and is currently a PhD candidate at the same University. She is also a researcher on the future directions of fiber art through post-pandemic online exhibitions and an exhibition director for the 2020 Sino-US Technology and Innovation in Fiber Art Exhibition. Her work has been exhibited at Tsinghua University Art Museum in Beijing, the M50 Creative Park in Shanghai, and Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris.