Immune response to Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer development

Breno Bittencourt de Brito, Fabian Fellipe Bueno Lemos, Caroline da Mota Carneiro, Andressa Santos Viana,Nilo Manoel Pereira Vieira Barreto, Gabriela Alves de Souza Assis, Barbara Dicarlo Costa Braga, Maria Luísa Cordeiro Santos, Filipe Antônio França da Silva, Hanna Santos Marques, Natália Oliveira e Silva, Fabrício Freire de Melo

Breno Bittencourt de Brito, Fabian Fellipe Bueno Lemos, Caroline da Mota Carneiro, Andressa Santos Viana, Nilo Manoel Pereira Vieira Barreto, Gabriela Alves de Souza Assis, Barbara Dicarlo Costa Braga, Maria Luísa Cordeiro Santos, Filipe Antônio França da Silva, Natália Oliveira e Silva, Fabrício Freire de Melo, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vit ória da Conquista 45029-094, Bahia, Brazil

Hanna Santos Marques, Campus Vitória da Conquista, Universidade Estadual do Sudoeste da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45031900, Bahia, Brazil

Abstract Gastric adenocarcinoma is a global health concern, and Helicobacter pylori (H.pylori) infection is the main risk factor for its occurrence.Of note, the immune response against the pathogen seems to be a determining factor for gastric oncogenesis, and increasing evidence have emphasized several host and bacterium factors that probably influence in this setting.The development of an inflammatory process against H.pylori involves a wide range of mechanisms such as the activation of pattern recognition receptors and intracellular pathways resulting in the production of proinflammatory cytokines by gastric epithelial cells.This process culminates in the establishment of distinct immune response profiles that result from the cytokine-induced differentiation of T naïve cells into specific T helper cells.Cytokines released from each type of T helper cell orchestrate the immune system and interfere in the development of gastric cancer in idiosyncratic ways.Moreover, variants in genes such as single nucleotide polymorphisms have been associated with variable predispositions for the occurrence of gastric malignancy because they influence both the intensity of gene expression and the affinity of the resultant molecule with its receptor.In addition, various repercussions related to some H.pylori virulence factors seem to substantially influence the host immune response against the infection, and many of them have been associated with gastric tumorigenesis.

Key Words: Gastric cancer; Helicobacter pylori; Immune response; Virulence factors; Polymorphisms

INTRODUCTION

About 1 million people are diagnosed with gastric cancer and more than 700000 individuals die from this neoplasm every year[1].That incidence makes gastric adenocarcinoma the fifth most common malignancy and the third cause of cancerrelated death worldwide[2].Among the multiple factors that influence the development of this disease,Helicobacter pylori(H.pylori) infection stands out.Gastric colonization by this gram-negative, spiral-shaped microorganism is the main risk factor for the occurrence of gastric adenocarcinoma, and worryingly it infects more than half of the world population[3].In that context, studies have emphasized the critical role of the interplays betweenH.pyloriand host immune system in carcinogenesis[4].

The immune response activation byH.pyloriinfection in the gastric mucosa occurs mainly through the triggering of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which leads to the activation of intracellular cascades that culminate in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines[5].The events taking place in the initial phase of infection lead to the recruitment of T cells, and the establishment of specific immune response profiles by T helper (Th) cells is determinant for the development ofH.pylori-related gastric disorders[6].H.pylorihas several virulence factors that favor its perpetuation in the gastric hostile environment.Some mechanisms triggered by these bacterial products play pivotal roles in the regulation of the host immune response and seem to influence the genesis of gastric neoplasms[7].On the other hand, specific host polymorphisms in genes that encode cytokines also interfere in the risk of developing the disease by altering the expression pattern of these mediators as well as the intensity of the signals that they activate[8].

Given the background, this article aims to provide a broad and updated review on how the immune response againstH.pyloriinfection influences in the development of gastric adenocarcinoma, discussing the main bacterial and host variables that interfere in the pathophysiology of the disease.

IMMUNE RESPONSE ACTIVATION BY H.PYLORI INFECTION

Complex host immune responses involving innate and adaptive mechanisms are induced byH.pyloriinfection[9-11].Gastric epithelium plays a pivotal role in the innate immune response to the bacterium because its cells make up the only cell phenotype in direct contact with the pathogen in conditions in which tissue damage is absent yet[12,13].The initial contact of the gastric epithelial cells with the pathogen activates pathogen-associated molecular pattern receptors including NOD1 and tolllike receptors (TLRs).These innate host defense mechanisms trigger cell signaling pathways that induce the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), activating protein-1, and interferon regulatory factors[14].Concerning the TLRs, it has been reported that gastric epithelial cells express TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR9, and TLR10, which interact with variousH.pyloriantigens such as lipoteichoic acid, lipoproteins, lipopolysaccharide, flagellin, HSP-60, neutrophil-activating protein A, DNA, and RNA[5,15,16].These receptors are very important to the induction of the expression of proinflammatory and antibacterial factors[5].For example, the translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus, aiming at activating the expression of genes associated with the inflammatory process, is directly associated with the engagement of TLRs, particularly TLR2, in a myeloid differentiation primary response 88-dependent process[17].Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 is a key TLR adapter protein used by all TLRs, except TLR3, and transmits signals that result in the induction of inflammatory cytokines[5].However, although TLRs are the most studied receptors,H.pyloripromotes the activation of PRRs other than TLRs.For instance,H.pyloripeptidoglycan, delivered into host cells by the type IV secretion system or through outer membrane vesicles secreted from the bacterium, is recognized by NOD1[18-21].As a result, the interaction betweenH.pyloriand PRRs leads to the expression of inflammatory cytokines, antimicrobial peptides, and type 1 interferon (IFN) by gastric epithelial cells[14].Subsequently, these cytokines and inflammatory mediators stimulate the recruitment of both polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells into the gastric mucosa[22,23].Lastly, it is important to mention that there are other cell components that also act in the induction of this inflammatory process.Recent reports have led to the conclusion that micro RNAs act as modulators ofH.pyloriinfection and concomitantly have their expression affected by the bacterium[24].

This inflammatory response is characterized by the chemotaxis of monocytes/ macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), B and T cells, and in particular, neutrophils, whose main chemoattractant is the interleukin (IL)-8 secreted by gastric epithelial cells as a result of the engagement of NOD1, for instance[25,26].Neutrophils are recruited to the lamina propria at the beginning ofH.pyloriinfection, and several specificH.pylorifactors are known to interact with these cells and modulate their responses[27,28].One of these factors is a protein produced byH.pyloriknown as neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP or neutrophil-activating protein A).HP-NAP can promote chemotaxis, endothelial adhesion, and production of reactive oxygen intermediates by neutrophils[29-31].Incubation of these cells with HP-NAP results in significant production of cytokines such as IL-12 and IL-23.The same effects of HP-NAP on cytokine secretion were also observed in macrophages and DCs.Therefore, it is possible to conclude that this protein acts on both neutrophils and monocytes, inducing the production of cytokines[30].

Mononuclear infiltration in the lamina propria is also characteristic ofH.pyloriinduced chronic infection[13].Human monocytes and macrophages are important coordinators of the immune response toH.pylori-derived products and signals from epithelial cells in direct contact with the bacterium on the surface of the mucosa[15].In this infection, both monocytes and macrophages, alongside the DCs, act as activators of adaptive immunity, because they are antigen-presenting cells, capable of expressing class II MHC molecules that activate CD4+ T cells[32].Furthermore, monocytes and macrophages also produce factors such as IL-12, responsible for inducing a polarized Th1 immune response, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which, except for IL-10, induce the amplification of the inflammatory response[16].Moreover, it is important to note that macrophages are also effector cells that are able to produce nitric oxide derived from the enzyme-inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS, NOS2) and reactive oxygen species, both associated with cellular damage[33].

Although in smaller numbers, DCs are also important in the immune response toH.pyloriinfection, especially because they represent an important bridge between the innate and adaptive immunities[26].These cells express a broad spectrum of PRRs, which enables them to capture antigens at the periphery and induce T naive cells to direct T cell differentiation[34].This role is played through three main signals: (1) presentation of foreign antigens in the form of peptides bound to class II MHC molecules to T cells; (2) costimulation of T cell differentiation; and (3) secretion of cytokines, particularly IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-1β, and TNF-α[35].Both aforementioned antigen-presenting cells exhibit remarkable secretion of IL-12, which enables the induction of a Th1-polarized immune response, responsible for the secretion of INF-γ and low amounts of cytokines characteristic of Th2 responses, such as IL-4 and IL-5[36-40].

Finally, mast cells represent an additional innate cell phenotype that is found within theH.pylori-infected gastric mucosa.These cells can be activated by variousH.pyloricomponents.For instance, the bacterial virulence factor VacA can induce mast cells to express multiple inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, TNF, IL-6, IL-23, and IL-10[41,42].Upon the stimulation of epithelial cells, macrophages, and DCs byH.pyloribacterial factors, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are recruited to the gastric mucosa, with preferential activation of CD4+ T cells in detriment to CD8+ cells[43-46].

IMMUNE RESPONSE PROFILES IN H.PYLORI INFECTION AND GASTRIC CANCER

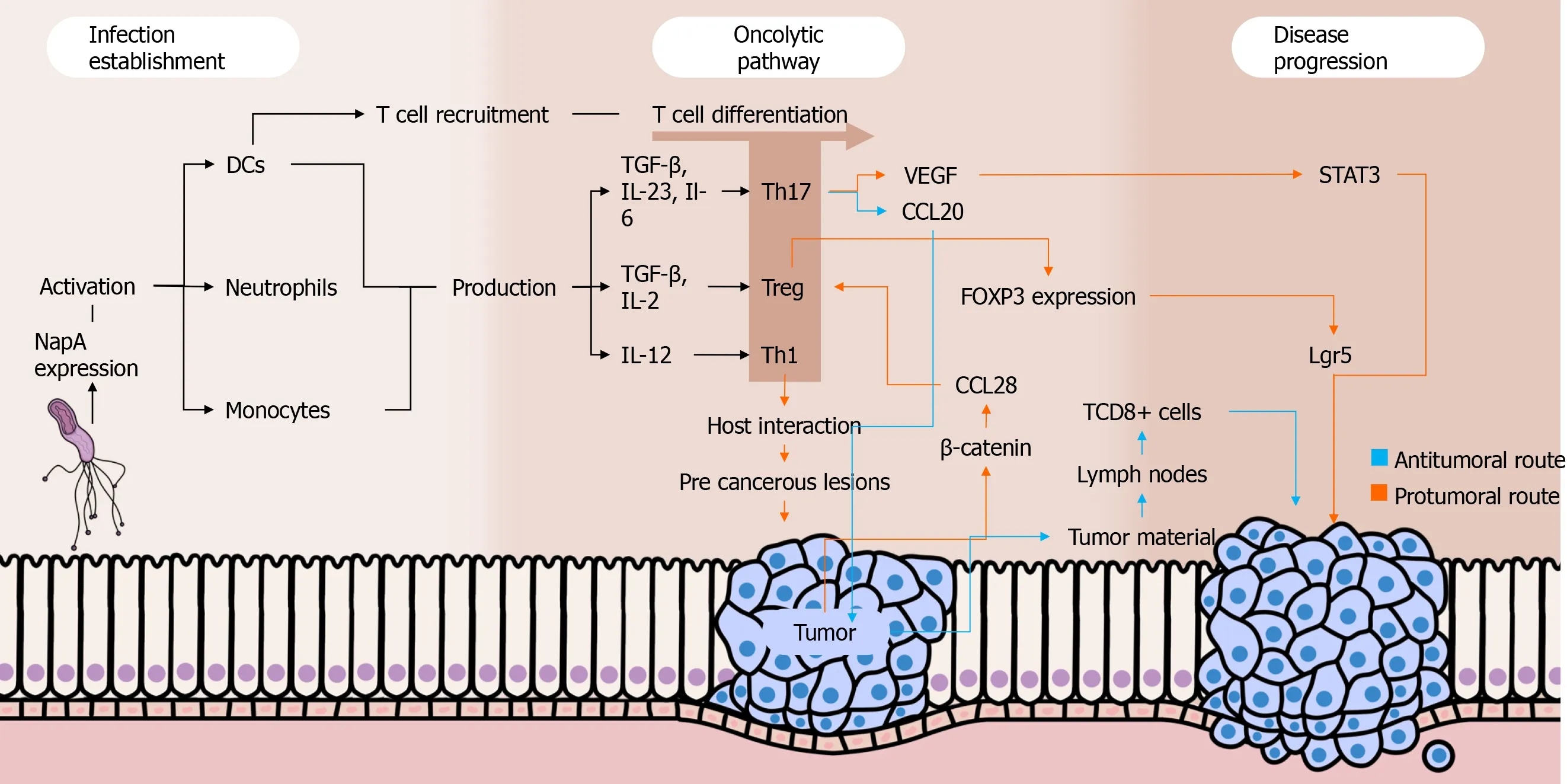

As aforementioned, the triggering of an immune response againstH.pyloriinvolves the activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and their migration to the gastric environment[47].Among the cytokines expressed in that context, those inducing the differentiation of naïve T cells into Th1 (e.g., IL-12), Th17 [e.g., transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), IL-23, and IL-6], and regulatory T cells (Treg) (e.g., IL-2 and TGF-β) cells stand out[48].

The establishment of a proinflammatory Th1 response in theH.pyloriinfection is associated with the development of corpus gastritis.Depending on further host and environmental variables, the aforementioned condition can result in gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, which are well-known precancerous lesions[48,49].Of note, our group previously demonstrated that Th1 response varies according to the age amongH.pylori-positive individuals.In that study, we observed higher gastric concentrations of Th1-related cytokines IL-2, Il-12p70, and INF-γ in adults than in children.Moreover, the levels of Th1 cytokines were directly correlated with the severity of gastric inflammation[50].

Regarding Th17 response, although other cytokines such as TGF-β and IL-6 are strongly related to this immune profile, current evidence emphasizes the pivotal role of IL-23 in its induction in the setting ofH.pyloriinfection[51,52].A study found that chronically infected IL-23(p19)-/-mice had reduced gastric expression of IL-17A as well as milder gastric inflammation and higher levels ofH.pyloricolonization compared to wild-typeH.pylori-positive mice[53].The IL-17A, in its turn, promotes the migration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes to the infection site and is an important component in the control ofH.pylorigastric infection[54].Previous studies using mice have shown that IL-17A-/-as well as IL-17RA-defficient individuals have a milder gastric neutrophil infiltration againstH.pyloriinfection than wild-type mice.Interestingly, the mice lacking IL-17RA signaling had an enhanced chronic inflammation with intense infiltration of B and CD4+ T cells into the gastric mucosa[55].

Dual roles have been attributed to Th17 responses in cancer settings.On one hand, this immune profile seems to be important in the immunosurveillance against malignant cells because it stimulates the migration of leukocytes into tumors and promotes the activation of antitumor CD8+ T cells.Intratumoral Th17 cells induce the expression of CCL20, a chemokine that attracts DCs to the tumor environment, as shown in a recently published paper by Chenet al[56].Subsequently, DCs phagocytose tumor material and migrate to lymph nodes, contributing to the activation of CD8+ T cells that migrate to the tumor environment through their chemotaxis to the Th17-induced CXCL9 and CXCL10[57].Moreover, studies have shown that Th17 cells can convert into Th1 lymphocytesin vivo, enhancing their antitumor effectiveness[58,59].When stimulated by IL-23 and IL-12 in an environment with absent or low TGF-β, Th17 cells are able to express IFN-γ and T-bet, important Th1-related molecules.Interestingly, Th17-derived Th1 cells have a more effective antitumor activity compared to other Th1 lymphocytes, and this may be due to the prolonged survival and superior functionality of the former compared to the latter[60].

On the other hand, the Th17 profile is involved in various protumor activities.First, IL-17 seems to promote angiogenesis because elevated intratumoral levels of that cytokine are associated with high expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and increased tumor vascular density[61].Complementally, the aforementioned cytokine stimulates cancer cells to release IL-6, which besides promoting vascular endothelial growth factor production enhances signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation, increasing the survival of malignant cells by suppressing apoptosis[62].Moreover, studies have described the existence of FOXP3+CD4+Th17 cells, which may play regulatory, protumor roles in cancer contexts.This phenomenon seems to occur along with low levels of Il-6 and IL-23 as well as with the presence of TGF-β, which activates FOXP3 expression[63].

A study carried out by Suet al[62] showed that IL-17 and RORγt (the main IL-17A transcription factor) were highly expressed in both tumor microenvironment and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of gastric cancer patients, mainly among those with metastasis.This data suggests that the presence of Th17 cells is directly associated with the occurrence of gastric cancer and with the severity of the disease.Indeed, a recently published study embracing stage IV gastric cancer patients from four cohorts have reinforced that theory because it found abnormally high levels of Th17 cell differentiation and activation of IL-17 pathways among patients with severe disease[64].Interestingly, another study evaluating the percentages of Th17 cells in PBMCs among gastric cancer patients before and after tumor resection observed a significant drop in the proportion of Th17 cells after the treatment[65].Of note, IL-27 has been highlighted as a crucial cytokine that plays dual roles in the regulation of the immune system.As far as this cytokine enhances T-bet expression through IL-27/IL-27Rα signaling and subsequent signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 phosphorylation leading to Th1 cell differentiation, IL-27 impairs Th17 responses by downregulating RORγT[66,67].In a recently published study, our group showed thatH.pylori-infected individuals have higher IL-27 levels in their serum and gastric mucosa than non-infected individuals.In contrast, there was a lack of IL-27 in both serum and gastric environment of gastric cancer patients, who also showed a remarkable Th17-polarized inflammatory pattern[68].

The Treg cells might play pivotal roles inH.pylori-induced gastric adenocarcinoma by favoring infection perpetuation and by repressing immune responses against malignant cells through the secretion of regulatory cytokines.Indeed, studies have observed that Treg cells are positively correlated with increased bacterial colonization[69], being also increased among gastric cancer patients[70,71].Three types of Treg cells have been described by studies: IL-10-secreting Tr1 cells, TGF-β1-producing Tr3 cells, and FOXP3-expressing CD4+CD25high Treg cells[72].The latter is a pivotal component in the scenario ofH.pyloricolonization, favoring the pathogen persistence in the gastric environment by suppressing the immune responses.A study demonstrated that FOXP3, TGF-β1, and IL-10 are highly expressed duringH.pyloriinfection, and the density of FOXP3+ Treg cells was higher in the gastric mucosa of infected individuals than inH.pylori-negative people.These cells have been associated with increased bacterial density among individuals with gastritis[73].

Advances in the understanding of the interplays between Treg responses and the development of gastric cancer have been achieved.Interestingly, a recent study including gastric cancer patients in various stages of the disease showed that high infiltration of FOXP3+Treg cells was associated with poor outcomes among individuals with advanced disease, but it was a predictor of better prognosis among patients with early-phase disease[74].Current evidence emphasizes the role of Wnt/βcatenin signaling in gastric carcinogenesis because 70% of gastric cancer patients have dysregulation in pathways associated with this signaling[75].β-catenin induces gastric cancer cells to produce CCL28, which strongly attracts Treg cells to the tumor environment.In this sense, a recently published study usingHelicobacter felis-colonized mice with gastric cancer found the block of β-catenin-induced CCL28 through anti-CCL28 antibodies leads to the suppression of gastric cancer progression by inhibiting Treg cells infiltration[76].

A surface glycoprotein known as neuropilin-1 seems to be crucial for the immunoregulatory events taking place in the tumor environment.The role of that molecule had already been well described in other malignancies, being related to cell migration, angiogenesis, and invasion[77].In a new investigation by Kanget al[78], the expression of neuropilin-1 was associated with increased levels of the regulatory cytokines IL-35, IL-10, and TGF-β1 as well as with increased infiltration of Treg cells and M2 macrophages in gastric cancer.Moreover, its expression was positively correlated to poorer outcomes, which indicates that neuropilin-1 has the potential to be used as a prognostic factor in gastric cancer patients.

Besides the aforementioned roles of Treg cells in gastric cancer development, Liuet al[79] found that these cells promote the expression of leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 by tumor cellsviaTGF-β1 and TGF-β1 signaling pathway, probably involving the aforementioned Wnt/β-catenin signaling.The leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 is a global stem cell marker whose overexpression is observed in gastric cancer, and it has also been positively correlated with tumor invasion, metastasis, and poor prognosis among individuals with that malignancy[80].Figure 1 summarizes the roles played by Th cells in the setting of gastric carcinogenesis.

Figure 1 Interplays between Helicobacter pylori, immune response, and gastric cancer.

POLYMORPHISMS IN GENES THAT ENCODE CYTOKINES AND GASTRIC CANCER

IL-1

The interleukin-1 family has 11 molecules that are able to interact with almost all human cells[81].Among these, the proinflammatory IL-1β and the antagonist receptor of IL-1 (IL-Ra) have been associated with an increased risk of developing gastric cancer[82-85].The genes encoding IL-1β and IL-1Ra are calledIL1BandIL1RN, respectively[86].Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) found in these genes alter the inflammatory response of these cytokines.The SNPs identified in the coding of IL-1B have a C-T transition base at -511, -31, or +3954 positions.For IL-Ra, the allele 2 (IL-RN*2) has been associated with inflammatory responses that increase the risk of disease development[87].

In the presence of any of the three aforementioned SNPs in the sequences that encode IL-1β, the production of this cytokine can be enhanced.This overexpression has been associated with the development of hypochlorhydria and atrophy of the gastric corpus, in addition to an increased risk for gastric cancer, especially onH.pyloripositive subjects[88-98].The production of IL1-Ra is mediated by a diversity of cytokines such as IL-1β, and the antagonistic function of the former controls the inflammatory response of the later.In this sense, the SNP IL-1RN*2 has been linked to an increased secretion of IL-1β[99-102].

IL-8

IL-8, also known as CXCL8, is a proinflammatory chemokine from the alpha subfamily (CXC)[103].It can be produced by several cells such as epithelial and endothelial cells, monocytes, macrophages, and tumor cells[104,105].Increased expression of IL-8 is promoted by various stimuli, including the initiation, modulation, and maintenance of the host inflammatory response againstH.pyloriinfection[106,107].This molecule induces the migration and proliferation of endothelial cells, contributing to angiogenesis and tumorigenesis, being related to increased cell migration, invasion, and metastasis[108].

TheCXCL8gene is located in chromosome 4q12-21 and possesses three introns, four exons, and a proximal promoter region[109].The genetic polymorphism IL8-251T> A (rs4073) has been associated with variations in the expression of IL-8 and increased risk of gastric cancer development mainly in Brazilian, Chinese, and Korean populations[110].Curiously, that polymorphism was not significantly associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer in the Japanese population, which might be related to specific environmental factors and genetic background[103].

IL-10

As previously discussed in this review, IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine; therefore, it inhibits the activity of some defense cells and limits the production of proinflammatory cytokines[111].Polymorphisms -1082, -592 and, less frequently, -819, can modulate IL-10 transcription, decreasing the expression of this cytokine, which can initiate a hyperinflammatory response that increases the risk of gastric lesions and cance[112-116].Therefore, these polymorphisms have been associated with a possible higher risk of gastric cancer, mainly in Asian populations but also in a study conducted with American subjects[117-120].

IL-2

IL-2 is a cytokine that plays proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory roles and is encoded by a gene located in chromosome 4q21.Among other repercussions, this molecule contributes to the proliferation of T regulatory cells and regulates the expansion and apoptosis of activated T cells[25,39].TheIL2GG variant genotype –330T> G inH.pylori-positive Asians and Brazilians as well as the SNP IL-2 + 114T> G and 330g/+ 114T haplotype inH.pylori-positive Brazilians have been associated with an increased risk of developing gastric cancer[121].

IL-4

Similar to IL-2, IL-4 also plays dual roles in the immune system, being encoded by a gene in chromosome 5q31.1[108].Its function in tumor progression is mainly related to the inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines in the setting of antitumor immune responses, favoring the perpetuation of malignant cells[107].Polymorphisms inIL4-590C/T rs2243250 CC, genotype CT + CC, andIL4haplotypes have been found to be associated with a higher risk of developing gastric cancer in the Chinese population[122].

IL-6

IL-6 is a cytokine that plays roles as an proinflammatory immune mediator and as an endocrine regulator[79].This protein is encoded by a gene located in chromosome 7 and has been found to be increased inH.pylori-positive individuals[108].Polymorphisms in theIL6-174C allele andIL6-174CC genotype are associated with an enhanced prevalence of diffuse-type gastric cancer, whereas theIL6-174CG has been related to intestinal-type gastric cancer[106].In addition, theIL6SNP -572 (G> C, rs1800796) has been emphasized as a potential genetic biomarker for increased gastric cancer risk in Asian populations[110].

IL- 22

IL-22 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that belongs to the IL-10 family.It participates in mucosal repair and epithelial immunity processes[123].Chinese individuals with the SNP rs1179251 (allele G) encoding IL-22 showed a higher risk of developing gastric cancer associated withH.pylori[124].Some SNPs of this cytokine have also been found in Chinese patients with increased risk for MALT gastric lymphoma induced byH.pylori(alleles C in rs2227485; A in rs4913428; A in rs1026788 and T in rs7314777)[125].

H.PYLORI VIRULENCE FACTORS, IMMUNE RESPONSE, AND GASTRIC CARCINOGENESIS

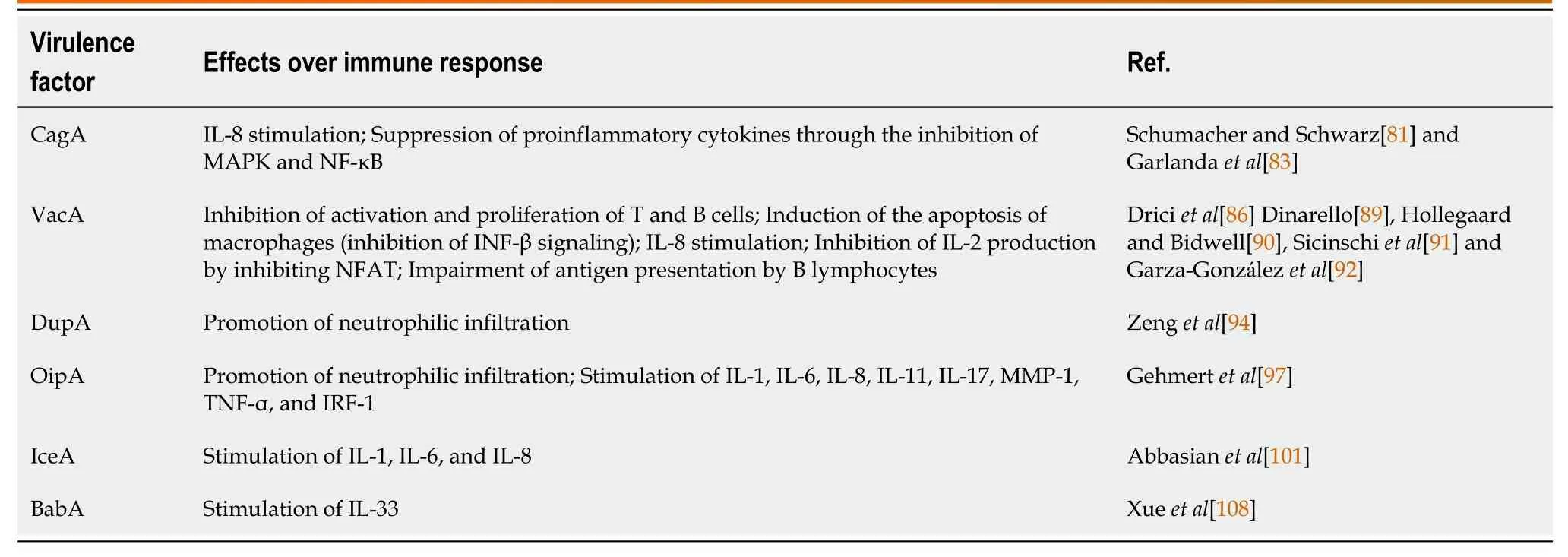

CagA

Infection withcagA-positiveH.pyloristrains is the main risk factor for the development of gastric cancer[126-129].CagA is a multifunctional, pore-forming protein that induces vacuolization, cell necrosis, and cell apoptosis in gastric epithelial cells[130-134].Of note, this virulence factor appears to induce an important modulation of the host immune system[135,136].A recently published study by Heet al[137] using mice revealed that CagA suppresses the expression of proinflammatory cytokines induced byH.pyloriinfection through the inhibition of the mitogenactivated protein kinase and NF-κB pathways.In addition, the study has shown, for the first time, that this virulence factor downregulates the posttranslational modification of TRAF6, obstructing the transmission of a signal downstream responsible for promoting the release of proinflammatory mediators.

Studies have described thatH.pylorihas a molecular mechanism ofCagA expansion through which its number of copies expands, consequently enhancing its virulence[138,139].The analysis of the PMSS1H.pyloristrain showed that bacteria that carry moreCagA copies also produce more toxin, leading to enhanced cell elongation and IL-8 induction[140,141].Yamaokaet al[142].proposes that the levels of IL-8 of the gastric mucosa are related to the presence of CagA and OipA.Both molecules seem to be involved in the induction of interferon regulatory factors and play a role in the complete activation of the IL-8 promoter, using different convergence pathways[143].

VacA

Vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) is a protein encoded by a monocistronic gene known asvacA.Secreted VacA molecules are 140 kDa initially, but they are rapidly cleaved into a 10 kDa domain (p10) to produce a mature 88 kDa protein[144,145].Generally, they are secreted as soluble proteins in the extracellular space; however, they are found on the bacterial surface as well[146].Moreover, this virulence factor is expressed by almost allH.pyloristrains[147].

VacA inhibits activation and proliferation of T and B cells, a process that induces the apoptosis of macrophages mainly through the inhibition of INF-β signaling.Moreover, this virulence factor induces an excessive release of IL-8[148].Specifically in T cells, VacA inhibits the production of IL-2, in addition to regulating the surface expression of the IL2-α receptor.This process is possibly due to the ability of VacA to inhibit the activation of the nuclear factor of activated T-cells, a global transcription factor that regulates immune response genes for T cell activation.The mechanism by which VacA inhibits activation of nuclear factor of activated T-cells is uncertain; however, it is believed that this virulence factor influences the calcium flow in the extracellular medium, which inhibits the calcineurin-dependent Ca2+-calmodulin complex[149].Other effects on these cells include the activation of intracellular signaling through MAP kinases, such as MKK3/6 and p38 as well as the Rac/Vav-specific nucleotide exchange factor[145].Studies with primary CD4+ T cells in humans have demonstrated that VacA inhibits the proliferation of activated T cells through a mechanism that is independent of the effect of VacA on nuclear factor of activated Tcells activation and IL-2 expression[150,151].In antigen presenting cells, VacA seems to interfere with the formation of vesicular compartments in macrophages infected withH.pyloricausing homotypic vacuolar fusion and consequent changes in their physiological properties.It has also been reported that VacA can interfere with the antigen presentation of B lymphocytes by interfering in the MHC II of these cells.Finally, blocking the activation and proliferation of this set of cells helpsH.pylorito resist the host immune response, establishing a persistent infection and with worse clinical outcomes[146].

The various positive VacA-linked bacterial genotypes are associated with a higher prevalence of malignant gastric lesions, in addition to a greater severity of inflammation induction by the pathogen.VacA is the most studied toxin inH.pyloridue to its versatility in relation to different receptors in different cell types and functions.VacA is directly involved in the formation of intracellular vacuoles, which provide the survival of the bacteria in the gastric environment, even after drug treatment.Therefore, other studies need to be developed with VacA in order to better understand the persistence of the pathogen in the gastric environment[152].

Duodenal ulcer promoter A

The duodenal ulcer promoter A (DupA) protein is anH.pylorivirulence factor whose gene is located in the plasticity zone of the bacterial genome[153].TheDupAgene contains two overlapping open reading frames (jhp0917 and jhp0918) that form a continuous locus[154].Of note, only strains that harbor both aforementioned segments are able to produce the DupA protein[155].

The initial studies on DupA show that its pathogenicity is closely linked to the development of duodenal ulcer[154].Based onin vitroandin vivostudies, such an outcome is believed to be due to the role of theDupAgene in the activation of NF-κB and activating protein-1, which enhance the infiltration of neutrophils with consequent expression of IL-8 in the antrum that promotes risk of these injuries[156,157].These findings have shown that predominant antral gastritis often leads to a reduction in somastatin, greater gastrin secretion, and consequently greater release of gastric acid and formation of duodenal ulcer[158].In this context, DupA expression is negatively correlated with the risk of gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric cancer[159,160].However, it has to be emphasized that DupA has not been associated with the development of duodenal ulcers in western populations[161,162].

OipA

The 34 kDa external inflammatory protein A (OipA), encoded by thehopHgene (hp0638), located approximately 100kb from the Cag Pathogenicity Island, belongs to the family of External Membrane Proteins.This protein is associated with gastric inflammation, being one of the mainH.pylorivirulence factors[163].

The attachment of gastric epithelial cells through OipA occurs with the induction of cellular apoptosisviathe Bcl-2 pathway, increased levels of Bax, and cleaved caspase 3[164].Notably, several studies have shown that positive OipA has been more frequent in individuals with precancerous lesions than those with gastritis alone[149,165-167].

TheOipA-positiveH.pyloristrains are more prone to gastric colonization, being also associated with a higher risk of peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer.This molecule strongly induces inflammation, and the infiltration of neutrophils as well as the production of IL-8 are significantly higher in oipA-positive strains compared to the negative ones[168].Some studies indicate that OipA induces the interferon regulatory factors 1, which binds and activates the element similar to the response element stimulated by IFN, to induce the genetic transcription of IL-8 and its production[153].In addition, NF-κB and activating protein-1 are also involved in the genetic transcription and production of IL-8 by gastric epithelial cells infected withH.pylori[169].

Other proinflammatory cytokines may also be present inH.pyloriinfection caused by the presence of OipA, such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-11 IL-17, matrix metalloproteinase-1, TNF-α, or CC chemokine ligand 5[170].This is similar to a response linked to the Cag Pathogenicity Island[8].However, depending on the OipA states in different strains ofH.pylori, the secretion of these cytokines may not be observed[171-173].

The genes that express functional OipA are strong factors of bacterial virulence and are linked to the genotypes VacA s1, VacA m1, blood group antigen-binding adhesin 2, and the Cag Pathogenicity Island gene and can act synergistically with each other to induce worse clinical outcomes of diseases caused byH.pylori[155].

IceA

The gene induced by contact with epithelium A (iceA) is a virulence marker still poorly described.The functions related to this virulence factor remain unclear and it possesses two variants: IceA1 and IceA2.H.pylorihas only oneiceAlocus from which the protein can be expressed.Therefore, the presence of both aforementioned variations indicates an infection by different strains of the pathogen[149].

The IceA relationship and the clinical outcomes of gastric diseases are still controversial[174].However, studies have emphasized that strains positive for this gene induce the release of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 more intensely than negative strains[175,176].Felicianoet al[177] demonstrated the possible role of IceA1 in the development of gastric cancer but not in peptic ulcers.In addition, Yakoobet al[178] demonstrated thaticeA2-positiveH.pyloristrains were more often associated with chronic active inflammation, gastric ulcer, and gastric adenocarcinoma.Studies indicate that IceA has its function preserved regardless of the presence of otherH.pylorivirulence factors[179-181].

To date, there seems to be a consensus that the global prevalence of IceA1 is higher than IceA2[174].However, although there is a greater expression of IceA1 than IceA2, the latter is associated with greater granulocytic and lymphocytic infiltration as well as atrophic gastritis[182].Abu-Talebet al[183] demonstrated in their study thatH.pyloriinfected individuals who express IceA1 or IceA2 alone do not develop gastric carcinoma.On the other hand, 75% of the patients who had both alleles (IceA1/IceA2) concomitantly developed gastric carcinoma.Strains that have positive IceA2 tend to stimulate IL-1, resulting in an increased risk of precancerous lesions in the gastric mucosa.This process can become worse if associated with the concomitant effects of other virulent factors, worsening inflammatory processes.Taken all together, theiceAgene is an important marker of severe gastric diseases that must be taken into account[149].

BabA

The mechanisms related to the BabA pathogenicity are still poorly elucidated.Nonetheless, studies have shown that BabA-dependentH.pyloricell adhesion have great relevance in the initial colonization of the pathogen[184].Moreover, BabA works by facilitating the entry of CagA and VacA into host cells[185].BabA-negativeH.pyloristrains have been associated with the development of mild gastric lesions and are rarely associated with gastric cancer.This means that BabA positivity might increase the risk of serious gastric lesions and carcinomas[186].

A study showed a greater expression ofIL-33mRNA in biopsies from patients infected withH.pyloricompared to noninfected individuals.Interestingly, a direct relationship was observed between blood group antigen-binding adhesin 2 and increased gastric levels of that cytokine[187].IL-33 plays an important role in immune regulation, providing protection after damage to epithelial cells[188].It also has the potential to reduce colonization in gastrointestinal infections[189].In addition, recent studies emphasize its likely role in the development of tumorigenesis[190].

Sialic acid A adhesin

Sialic acid A adhesin (SabA) is anH.pylorimembrane protein whose expression has been explored as a biomarker for increased risk of developing gastric cancer[191,192].Yamaokaet al[193] demonstrated that SabA is positively associated with gastric cancer, intestinal metaplasia, and body atrophy and is negatively associated with duodenal ulcer.H.pyloriuses SabA to recognize the Lewis X antigen from gastric epithelial cells, and this virulence factor has been associated with non-opsonic activation of human neutrophils[194,195].SabA mediates antigen binding to sialyl-Lewis, which is an established tumor and gastric dysplasia marker[196].The available data on this issue highlights how harmful such adhesion can be to the gastric epithelium; however, further studies are needed to better understand the underlying immune system responses related to this molecule[197].Table 1 shows how theH.pylorivirulence factors interact with the immune system.

Table 1 Roles of Helicobacter pylori virulence factors on host immune response

Heat-shock protein 60

Heat-shock protein 60 (hsp60) is known to have substantial immunogenic properties.Studies have demonstrated that hsp60 promotes cell signaling upon myeloid and vascular endothelial cells[198].H.pylori-expressed hsp60 seems to play a role in bacterial adhesion to gastric epithelial cells and mucin[199].In addition, that virulence factor has been shown to effectively inhibit human PBMCs.A study by Maguireet al[200] demonstrated that the inhibitor effect over human PBMCs was more potent with hsp60 fromH.pylorithan hsp60 fromChlamydia pneumoniaeor human mitochondria.Evidence has shown that hsp60 also promotes immune system responses through the activation of TLRs in human gastric epithelial cells and induces IL-8 expression through TLR-2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in human monocytes[201,202].Another study evaluating the effects of hsp60 over human monocytes demonstrated that it seems to promote an upregulation of cytokines such as IL-1a, IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and TGF-β[203].Regarding the oncogenic roles related to this molecule, an enhanced gastric cancer cell and promotion of tube formation by umbilical vein endothelial cells have been positively associated with hsp60, but effects on cell proliferation and cell death prevention have not been attributed to the protein[204].

CONCLUSION

The knowledge on the relationship betweenH.pyloriinfection, the immune system, and oncogenesis is crucial for the understanding of the mechanisms involved in the onset and progression of gastric cancer.Although considerable advances have been achieved in this research field, much has to be done in order to describe underlying mechanisms related to theH.pylori-related carcinogenesis.A better comprehension on this issue could be useful for the development of tools that may aid in the prevention as well as in the prognostic prediction and treatment of such an important disease.Here, we gathered data showing thatH.pyloriinfection promotes multiple immune response activities, such as Th cell polarizations that are closely related to mechanisms associated with gastric carcinogenesis.

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2021年3期

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2021年3期

- World Journal of Meta-Analysis的其它文章

- Post COVID-19 infection: Long-term effects on liver and kidneys

- Dengue hemorrhagic fever and cardiac involvement

- Glycated haemoglobin reduction and fixed ratio combinations of analogue basal insulin and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: A systematic review

- Impact of Streptococcus pyogenes infection in susceptibility to psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Extraintestinal infection of Listeria monocytogenes and susceptibility to spontaneous abortion during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis