Causes of severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia: a multicenter study of three regions in China

Xiao-Yue Dong· Qiu-Fen Wei· Zhan-Kui Li· Jie Gu· Dan-Hua Meng· Jin-Zhen Guo· Xiao-Li He·Xiao-Fan Sun· Zhan g-Bin Yu· Shu-Ping Han

Abstract Background Available evidence suggests that our country bear great burden of severe hyperbilirubinemia.However, the causes have not been explored recently in different regions of China to guide necessary clinical and public health interventions.Methods This was a prospective, observational study conducted from March 1, 2018, to February 28, 2019.Four hospitals in three regions of China participated in the survey.Data from infants with a gestational age ≥ 35 weeks, birth weight ≥ 2000 g, and total serum bilirubin (TSB) level ≥ 17 mg/dL (342 μmol/L) were prospectively collected.Results A total of 783 cases were reported.Causes were identified in 259 cases.The major causes were ABO incompatibility ( n= 101), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency ( n= 76), and intracranial hemorrhage ( n= 70).All infants with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency were from the central south region.Those from the central south region had much higher peak total bilirubin levels [mean, 404 μmol/L; standard deviation (SD), 75 μmol/L] than those from the other regions (mean, 373 μmol/L; SD, 35 μmol/L) ( P< 0.001).Conclusions ABO incompatibility was the leading cause in the east and northwest regions, but cases in the central south region were mainly caused by both ABO incompatibility and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, and infants in this region had a much higher peak total bilirubin level.Intracranial hemorrhage may be another common cause.More thorough assessments and rigorous bilirubin follow-up strategies are needed in the central south region.

Keywords Causes · Hyperbilirubinemia · Jaundice · Neonate

Introduction

Hyperbilirubinemia can cause acute bilirubin encephalopathy (ABE), and even kernicterus, a condition that can cause neurologic damage and death [1].Severe hyperbilirubinemia and its sequelae continue to be a very serious problem in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [2- 6].Hospitalbased studies have consistently reported significantly high rates of exchange transfusion and ABE or kernicterus in LMICs, including China [7- 9].

The most prevalent causes associated with hyperbilirubinemia are ABO incompatibility, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, Rh incompatibility, and perinatal infection [10, 11], but the causes of hyperbilirubinemia vary in different populations according to the data from Europe [12- 14], the United States [15], Canada [16] and, Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [11].Recent data to explore the causes of severe hyperbilirubinemia in our country are limited.The latest study in China was a multicenter survey of bilirubin encephalopathy conducted in 2009 that found that common causes of bilirubin encephalopathy were sepsis, ABO incompatibility, G6PD deficiency, Rh incompatibility, and visceral hemorrhage [5].

We conducted this multicenter study in four hospitals from three regions of China (East, central South and Northwest China) to estimate the current underlying causes of severe hyperbilirubinemia and determine regional differences in causes and clinical features, which would be valuable in guiding improvements health care policies and practices in China as a whole and for specific regions in China.

Methods

This was a prospective, observational study conducted from March 1, 2018, to February 28, 2019.Four hospitals in three regions of China (one in East China, one in central South China, and two hospitals in Northwest China) participated in the survey.The four participating hospitals are the highest level hospitals (tertiary maternal and child health centers) in the capital cities of each region.Approximately 6000-8000 newborns were admitted to the hospitals in each region during the study period.Inclusion criteria included infants with estimated gestational age ≥ 35 weeks, birth weights ≥ 2000 g, and total serum bilirubin (TSB) levels ≥ 342 μmol/L (17 mg/dL).

Participants were enrolled by each hospital in order of admission time.In this study, we designed a standardized data collection paper form and a standardized clinical research database.Each hospital reported monthly to the research center, and the number of subjects admitted to the hospital and sent the paper form of each subject monthly to the research center.Two staffof the research center were responsible for checking the information and inputting the information into the database.

Maternal data (age, number of pregnancies, maternal diseases, ethnicity), perinatal data (gestational age in weeks, sex, birth weight in grams, Apgar score at 1, 5, and 10 min, date of birth, date of discharge from hospital), and neonatal data (liver function tests, diagnosis, intracranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) signs, characteristics of ABE and management) were collected with a standardized data collection form designed by the research team.Researchers reported the numbers of infants with severe hyperbilirubinemia and mailed the survey forms to the data management center monthly.Two medical staffin the data management center rechecked the information and entered the information into the database.

ABO and Rh incompatibility were defined as direct Coombs test positive or antibody release test positive or hematocrit ≤ 35%, reticulocytes ≥ 6% and the history of mother-infant ABO incompatibility because our country do not implement the strategy of performing direct Coombs test in mother-infant ABO incompatibility newborns after birth and many infants with severe hyperbilirubinemia readmitted late, resulting in the destruction of most of the sensitized red blood cells and leading to negative results of direct Coombs test.G6PD deficiency was defined as G6PD activity < 8 U/g hemoglobin [17].Routine testing for G6PD activity was performed in the central south region because the population in South China had a high frequency of G6PD deficiency [18].Testing for G6PD activity was performed in infants with the presence of hemolysis and without possible isoimmunization in the east and northwest regions.Intracranial hemorrhage was defined as positive signs of intracranial hemorrhage on MRI, if performed.

The management of severe hyperbilirubinemia was carried out according to 2004 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guideline for management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant with a gestation of 35 or more weeks.Patients underwent neurologic evaluations using the bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction (BIND) protocol according to the characteristics of ABE [19- 22].Overt ABE was defined as a BIND score of 4 to 9.Scores of 4 to 6 represented moderate ABE, and scores of 7 to 9 represented severe ABE, which will most likely progress to sequelae or death [23].The ethics committee of Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital approved this study (No.[2018] 72).It was also approved by each participating center.

Statistical methods

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the data.Continuous variables were analyzed using an independent Student'sttest.Fisher's exact test was used to test associations between overt ABE and discharge.χ2 tests were used to test associations between all other categorical variables.APvalue < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

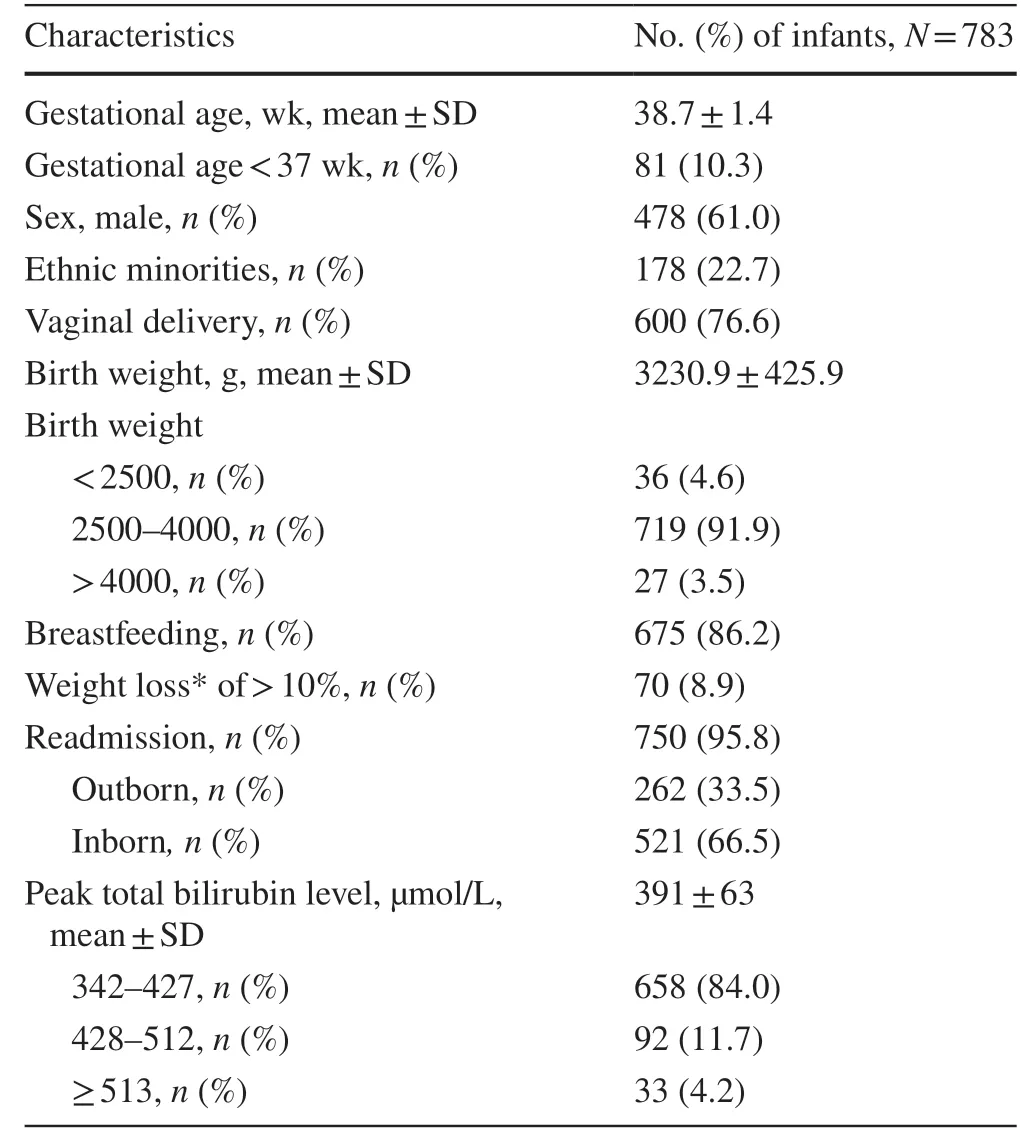

From March 2018 to February 2019, 783 cases of severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia met the inclusion criteria for this study and were analyzed.Demographic characteristics and peak TSB are shown in Table 1.The mean peak bilirubin level was 391 μmol/L (standard deviation [SD], 63 μmol/L).A total of 92 patients developed extreme hyperbilirubinemia (TSB level range, 428-512 μmol/L) [9], and 33 patients developed hazardous hyperbilirubinemia (TSB level range 513-902 μmol/L) [9].Ethnicity reported was ethnic Han (605, 77.3%) and ethnic minorities (178, 22.7%).Seventy patients (8.9%) had lost more than 10% of their birth weight at the time of admission.A total of 262 patients (33.5%) were outborn infants.

Table 1 Characteristics and peak total serum bilirubin of the study population

The causes of hyperbilirubinemia are summarized in Table 2.Causes were identified in 259 cases (33.1%).ABO incompatibility (n= 101) was the most common cause, followed by G6PD deficiency (n= 76).Seventy infants hadintracranial hemorrhage, of whom 30 had subdural hemorrhage, 29 had subarachnoid hemorrhage, 6 had subdural hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage, and 5 had cerebral hemorrhage.Thirty patients had cephalohematoma.Thirteen patients were diagnosed with sepsis, of whom 4 had a positive blood cultures.Two patients had Rh incompatibility.We divided the subjects into three groups according to bilirubin level.The percentage of infants with G6PD defi-ciency and subdural hemorrhage in TSB level ≥ 513 μmol/L group was much higher than other groups (P< 0.05).No difference was observed in the number of infants with other causes.

Table 2 Causes of severe hyperbilirubinemia

The central south, east, and northwest regions reported 446, 112, and 225 cases of severe hyperbilirubinemia, respectively (Fig.1).Most cases (57.0%) were reported by the central south region.We compared the causes and clinical features between the central south region and the other two regions (Table 3).The most common cause in the central south region was G6PD deficiency (17.0%), followed by ABO incompatibility (10.3%).All 76 cases with G6PD deficiency were reported in the central south region.The mean gestational age and birth weight in the central south region were less than those in other regions.Although 3.6% of patients in the other two regions presented with G6PD activity, none of the cases could be attributed to G6PD deficiency.Patients in the central south region had a much higher peak total bilirubin level [404 μmol/L, standard deviation (SD) 75 μmol/L] than those from the other regions (mean, 373 μmol/L; SD, 35 μmol/L) (P< 0.001).The percentages of extreme hyperbilirubinemia (TSB ≥ 42 8 μmol/L, < 513 μmol/L) and hazardous hyperbilirubinemia (TSB ≥ 513 μmol/L) in the central south region were much higher than those in the other two regions (16.1 vs.5.9%, 6.5 vs.1.2%, respectively;P< 0.001).The percentages of Intracranial hemorrhage in the central south region were lower than those in the other two regions (4.9 vs.14.2%, respectively;P< 0.001) (Table 3, Fig.1).

Fig.1 Number of cases re p orted in the east, central south, and northwest regions.The central south, east, and northwest regions reported 446, 112, and 225 cases of severe hyperbilirubinemia, respectively.There were 345, 72, and 29 infants with TSB levels ranging from 342-427 μmol/L, 428-512 μmol/L, and ≥ 513 μmol/L in the central south region, respectively.There were 106, 6, and 0 infants with TSB levels ranging from 342-427 μmol/L, 428-512 μmol/L, and ≥ 513 μmol/L in the east region, respectively.There were 207, 14, and 4 infants with TSB levels ranging from 342-427 μmol/L, 428-512 μmol/L, and ≥ 513 μmol/L in the northwest region, respectively

Table 3 Characteristics and causes of severe hyperbilirubinemia in the central south region and the other two regions

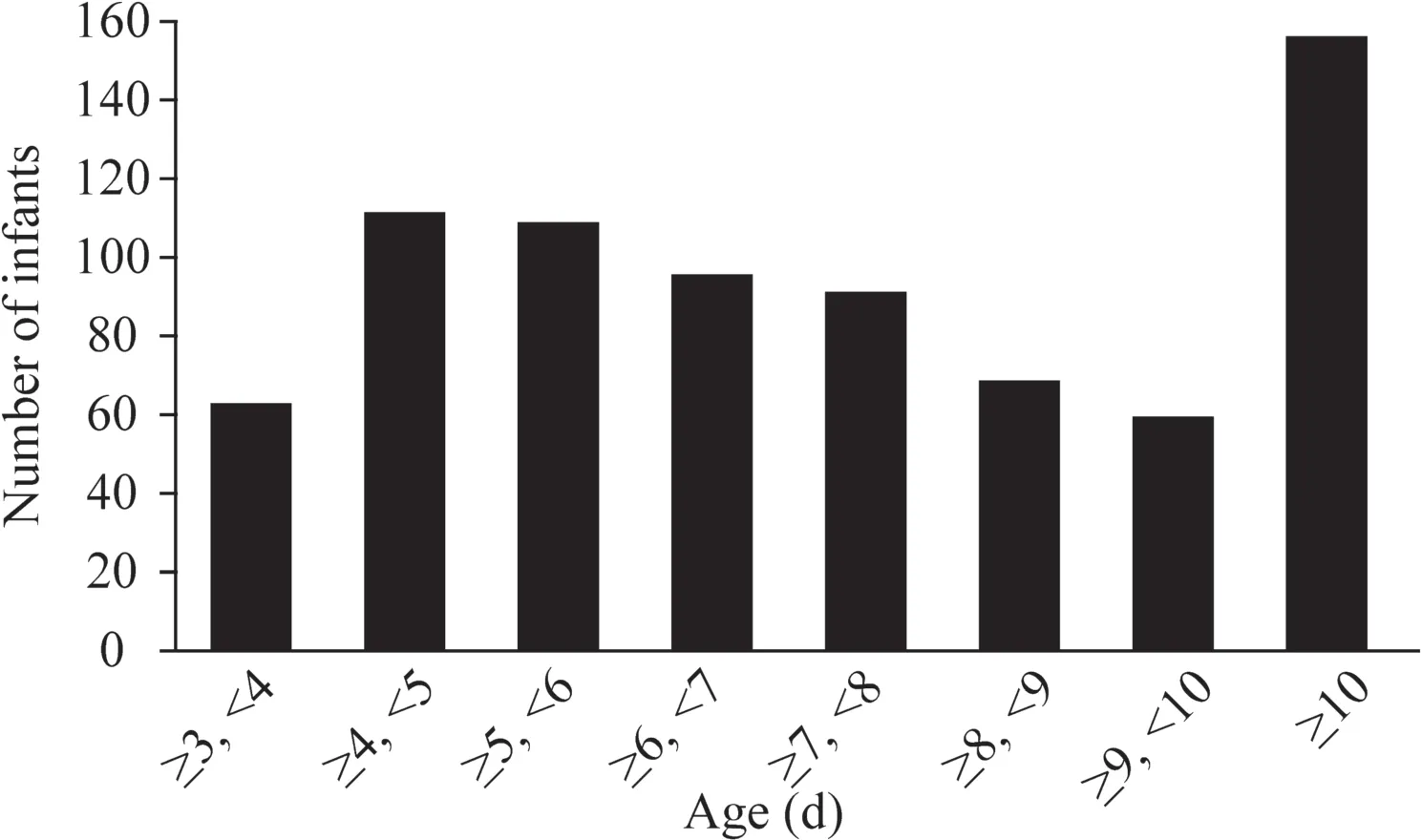

Only 33 of 783 patients were identified before they were discharged from the hospital at birth; most cases (95.8%) and all bilirubin encephalopathy cases were identified in the readmission cohort.The predischarge and readmission groups had similar birth weights, gestational ages, sex distributions and peak total bilirubin levels (Table 4), but in most cases (72.7%), the causes, mainly ABO incompatibility (39.4%) and G6PD deficiency (27.3%), were identified in the predischarge cohorts.No difference was observed in the number of infants with other specific diagnoses (Table 4).The median age at presentation in the predischarge cohort was 2.55 days (SD, 0.65 days), and that in the readmission cohort was 7.69 days (SD, 4.4 days) (P< 0.001).The average hospital length of stay (LOS) after birth of those readmittedwas 2.87 days (SD, 1.07 days) (Fig.2), and most infants (57.2%) were discharged from the hospital within 3 days after birth.The average age at readmission was older than 7 days (mean, 7.69; SD, 4.4 days); most infants (65.4%) were readmitted after 7 days of age, and 17.5% of infants had their maximum TSB measured after 10 days of age (Fig.3).

Table 4 Causes of severe hyperbilirubinemia identified before and after initial discharge from the hospital

Fig.2 The hospital length of stay (LOS) in 750 readmitted infants.There were 118, 311, 197, 85, and 39 infants with LOSs of 1-2; ≥ 2, < 3; ≥ 3, < 4; ≥ 4, < 5; and ≥ 5 days, respectively, among 750 readmitted infants.The average LOS of the readmitted patients was 2.87 days.Four hundred and twenty-nine infants (57.2%) were discharged within 3 days after birth

Fig.3 Age at readmission in 750 re-admitted infants.Among 750 re-admitted infants, 62, 111, 108, 95, 91, 69, 59, and 155 infants were re-admitted with severe hyperbilirubinemia at the ages of ≥ 3, < 4; ≥ 4, < 5; ≥ 5, < 6; ≥ 6, < 7; ≥ 7, < 8; ≥ 8, < 9; ≥ 9, < 10, and ≥ 10 days after birth, respectively.The average age at readmission was older than 7 days [mean, 7.69; SD, 4.4 days].Most infants (65.4%) had their maximum TSB measured after 7 days of age, and 131 (17.5%) infants had it measured after 10 days of age

Twenty-five infants were reported to have neurological abnormalities consistent with ABE.Seven of these infants had moderate ABE.Five cases were severe ABE; of whom, 3 infants had neurological abnormalities at final discharge, including lethargy (n= 3), seizures (n= 1), and opisthotonos (n= 1).One infant died shortly after discharge.

Discussion

At present, no definitely pathological factors can be found in most severe hyperbilirubinemia.In this study, the causes of severe hyperbilirubinemia could not be identified in 66.9% of the cases.Kuzniewicz et al., Sgro et al.and Yadollah [15, 16, 24] reported similar results.However, we found that most patients (72.7%) in the predischarge cohort received a specific diagnosis, mainly ABO incompatibility or G6PD deficiency.Sgro et al.identified TSB ≥ 425 μmol/L as a cause in 41.4% of 73 predischarge cases [16].The difference may be the result of differences in management strategies for jaundice during hospitalization between the two countries.In the four hospitals in our study, infants were routinely screened for jaundice every day during hospitalization after birth, and the average age at representation was 2.55 days.Our results suggest that these two hemolysis events may present as acute neonatal hemolytic events and cause severe hyperbilirubinemia very early, and monitoring infants at risk of ABO incompatibility and G6PD deficiency more frequently may effectively reduce severe hyperbilirubinemia during hospitalization.

This study found that the common causes of severe hyperbilirubinemia were ABO incompatibility (12.9%) and G6PD deficiency (9.7%); Sgro et al.similarly found ABO incompatibility (18.6%) and G6PD deficiency (7.7%) in cases with TSB ≥ 425 μmol/L in Canada [16].The distribution of causes is different according to differences in populations and TSB cut offvalues.Ebbesen et al., Manning et al., and Gotink et al.found that isoimmunization was relatively more common in Europe (Denmark, the UK and Ireland, and the Netherlands, respectively) [12- 14].Kuzniewicz et al.found that G6PD deficiency (21%) was the common cause in cases with TSB ≥ 513 μmol/L in the United States [15], and Gamaleldin et al.found that ABO (23.7%) and Rh incompatibility (8.8%) were the common causes in cases with TSB ≥ 427 μmol/L in Egypt [25].Olusanya et al.found that ABO incompatibility, G6PD deficiency, Rh incompatibility and sepsis placed infants at increased risk of severe hyperbilirubinemia in LMICs [11], similar to the results of a national multicenter survey of bilirubin encephalopathy in Chinese newborn infants conducted in 2009 [7].However, this study found that Rh incompatibility (0.26%) and sepsis (1.66%) were not common causes, which indicate that perinatal-neonatal care for these two conditions has improved in China in the last decade.Previous data to investigate the association between intracranial hemorrhage and severe hyperbilirubinemia are limited.Our study revealed that 70 patients (8.9%) experienced intracranial hemorrhage; of whom, 92.9% had subdural and subarachnoid hemorrhaging.Twenty-eight patients had ABO incompatibility, G6PD deficiency or cephalohematoma, potentially suggesting that intracranial hemorrhage may not be the main cause of but rather one of the accompanying factors aggravating jaundice.However, we identified 42 patients with a single intracranial hemorrhage diagnosis, despite the fact that only 54% underwent MRI.This might be accurate, as intracranial hemorrhage leads to extravascular hemolysis, resulting in excessive bilirubin production and the mechanism is similar to cephalohematoma.MRI diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage and subdural hemorrhage was significantly better than traditional ultrasound examination, which may reduce the missed diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhage.This study found that most types of intracranial hemorrhage associated with severe hyperbilirubinemia were subdural hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage, which were mainly related to birth injury, cerebral blood fl ow instability.Proper management during childbirth and avoidance of hypoxemia, hyperxemia, hypercapnia, and hypocapnia in the resuscitation of high-risk infants after birth will be assist in further preventing intracranial hemorrhage and severe hyperbilirubinemia.

In this study, the number of cases and peak bilirubin levels reported by the central southern region were significantly higher than those reported by the other two regions.The hospitals in our study are all tertiary maternal and child health hospitals located in capitals of each region, and the number of patients admitted in each region was approximately the same (6000-9000 year); therefore, we anticipated that the distribution of the incidence of severe hyperbilirubinemia in China was uneven, and the central south region was the leading contributor to infants who developed severe hyperbilirubinemia in these three regions in China.The hospital in the central south region reported 29 cases of hazardous hyperbilirubinemia and 10 cases of overt ABE over 1 year; among these cases, 3 infants had neurological abnormalities at final discharge, and 1 infant died shortly after discharge.However, a study from America reported only 47 cases of hazardous hyperbilirubinemia and 4 cases of chronic bilirubin encephalopathy during a 17 year period from 1995 to 2011 [15].The high rate of severe hyperbilirubinemia and high risk of serious sequelae in newborns from the central south region may be due to the following reasons.First, central South China is a minority settlement.Many ethnic minorities live in rural and mountainous regions where medical resources are limited, and it is not uncommon for mothers to resort to vitamins or herbal preparations as first-line treatments instead of going to the hospital.The sixth national population census in 2010 showed that ethnic minorities accounted for 8.49% of the total population [7].In our study, ethnic minorities accounted for 22.7% of all cases, which is higher than the results of the sixth national population census, indicating that the incidence of severe hyperbilirubinemia is higher in ethnic minorities than in those of Han ethnicity.Similar to this result, the 2009 epidemiological survey of bilirubin encephalopathy in China reported that the incidence of bilirubin encephalopathy in ethnic minorities was higher than the incidence in those of Han ethnicity [7].Second, South China is a high-incidence area of G6PD deficiency in China.We found that all cases with G6PD deficiency were reported in the central south region.Furthermore, the percentage of infants with G6PD deficiency in TSB level range ≥ 513 μmol/L group was much higher than other groups, which suggested that G6PD deficiency was more likely to cause more severe hyperbilirubinemia than other causes.In conclusion, central South China is a minority settlement, and local populations have a high frequency of G6PD deficiency, which may be two important reasons for the high incidence of severe hyperbilirubinemia in this region.Our study also found that the gestational age and birth weight of infants in the central south region were less than those in other regions; these factors may increase the risk of severe hyperbilirubinemia.The percentages of intracranial hemorrhage in the central south region were lower than those in the other two regions, which may be related to percentages of infants underwent MRI in the central south region was less than those in other regions (36.7% vs.76.5%, respectively).

One of the major concerns for infant health after early discharge is readmission for jaundice, especially in areas where services of proper predischarge screening and post-discharge follow-up for newborns are not accessible [26].In our study, most cases (95.8%) and all bilirubin encephalopathy cases were from the readmission cohort.The average LOS of these readmitted patients was 2.87 days, but the average age at readmission was more than 7 days (7.69 days).The Chinese Medical Association issued an expert consensus statement in 2014 recommending infant follow-up within 48-72 h after discharge [27].Our results indicate that efforts to improve adherence to the Chinese Medical Association's recommendations for the management of hyperbilirubinemia are urgently needed.Education of health care providers, mothers, and families and ensuring infant follow-up, especially for infants discharged early, infants with risk factors of hyperbilirubinemia, especially with the risk of ABO incompatibility and G6PD deficiency are essential.

There are several limitations to our study.First, routine testing for G6PD activity was performed in only the south region because the associated population has a known high frequency of G6PD deficiency.Moreover, as older red blood cells with G6PD deficiency are broken down during an acute hemolytic events, it is difficult to detect G6PD activity, which may result in false normal levels [28].Furthermore, not all subjects performed cranial MRI and some severe hyperbilirubinemia may be related to genetic factors, but we did not perform genetic testing in neonates with severe hyperbilirubinemia.These conditions may have caused a certain number of missed diagnoses.In this study, the etiological analysis of the three regions cannot represent other regions and the whole country.Finally, this study used the traditional BIND score to grade ABE instead of the more updated bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction (BINDM) which incorporates a measure of the abnormality of the upward gaze [19, 29].

In conclusion, ABO incompatibility and G6PD deficiency were the most common causes of severe hyperbilirubinemia in China.Intracranial hemorrhage may be another common cause.ABO incompatibility was the leading cause in the east and northwest regions, but infants in the central south region presented with both ABO incompatibility and G6PD deficiency and had a much higher peak total bilirubin level.The central south region has a high burden of severe hyperbilirubinemia and bilirubin encephalopathy.Efforts to improve adherence to the Chinese Medical Association's recommendations for the management of hyperbilirubinemia are urgently needed, and more thorough assessments and rigorous bilirubin follow-up strategies are needed in the central south region.

Authors' contributions DXY conceptualized and designed the study and drafted the initial manuscript; HSP and YZB conceptualized and designed the study, conducted the initial analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; WQF, LZK, GJ, MDH, GJZ, HXL, and SXF coordinated and supervised the data collection at their own sites, and critically reviewed the manuscript.All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FundingThis study was funded by Jiangsu Provincial Commission of Health and Family Planning (H2018011), Nanjing Science and Technology Plan (201803015), Jiangsu Provincial Maternal and Child Health Association Research Project (FYX201805), Jiangsu Province Key Research and Development Plan-Social Development (BE2019620), Six Talent Peaks Projects in Jiangsu Province (LGY2017004), and Jiangsu Province Women and Children Health Key Talents (FRC201740).

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by the ethics committee of the NanJing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital (Identifier: [2018]72).

Conflict of interestNo financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年3期

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年3期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- COVID-19 ocular findings in children: a case series

- Associations between measures of pediatric human resources and the under-five mortality rate: a nationwide study in China in 2014

- Genetic etiologies associated with infantile hydrocephalus in a Chinese infantile cohort

- Hedgehog signaling pathway gene variant influences bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely low birth weight infants

- Maternal mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in Beijing, China

- Distinctive clinical and laboratory features of COVID-19 and H1N1 infl uenza infections among hospitalized pediatric patients