Is COVID-19-induced liver injury different from other RNA viruses?

Marwan SM Al-Nimer

Marwan SM Al-Nimer, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Hawler Medical University, Erbil 44001, Iraq

Marwan SM Al-Nimer, College of Medicine, University of Diyala, Baqubah 32001, Iraq

Abstract Coronavirus disease 2019 is a pandemic disease caused by a novel RNA coronavirus, SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is implicated in the respiratory system.SARS-CoV-2 also targets extrapulmonary systems, including the gastrointestinal tract, liver, central nervous system and others.SARS-CoV-2, like other RNA viruses, targets the liver and produces liver injury.This literature review showed that SARS-CoV-2-induced liver injury is different from other RNA viruses by a transient elevation of hepatic enzymes and does not progress to liver fibrosis or other unfavorable events.Moreover, SARS-CoV-2-induced liver injury usually occurs in the presence of risk factors, such as nonalcoholic liver fatty disease.This review highlights the important differences between RNA viruses inducing liver injury taking into consideration the clinical, biochemical, histopathological, postmortem findings and the chronicity of liver injury that ultimately leads to liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Key Words: Liver injury; COVID-19; RNA-viruses; Risk factors; Liver enzymes; Liver fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

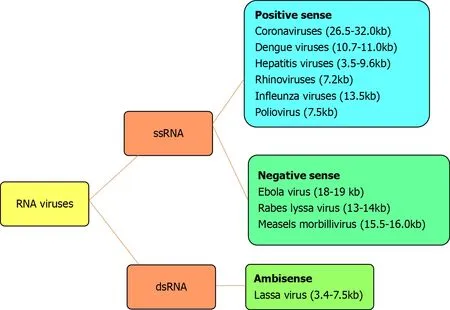

The genetic material of RNA viruses is usually single-stranded RNA and occasionally double-stranded.Examples of single-stranded RNA viruses are rhinoviruses, influenza viruses, coronaviruses, dengue viruses, hepatitis viruses, west Nile viruses, Lassa virus, Ebola virus, Rabies lyssavirus, polioviruses and measles morbillivirus.Examples of double-stranded RNA viruses are rotaviruses and picobirnaviruses.According to the polarity of the viral envelope, they are grouped into positive-sense and negative-sense (Figure 1).Coronaviruses are RNA viruses that belong to the coronaviridae family.These viruses are enveloped with a positive single-stranded RNA genome sized 26.4-31.7 kilobases[1].The genome of coronaviruses is larger than other RNA viruses (Figure 1).

In humans, coronaviruses cause mild respiratory symptoms (e.g., rhinoviruses) or lethal respiratory stress syndrome [e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)].In mice, coronaviruses cause hepatitis and encephalomyelitis[2,3].Extrapulmonary organ dysfunction is also reported by coronavirus infections in humans.Dysfunction of the hepato-biliary system is an uncommon clinical presentation of coronavirus infections.

The liver is one of the extrapulmonary organs attacked by COVID-19[4-6].Some SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-infected people showed abnormal liver function tests, and other patients showed liver injury as a late sequel of multiple organ dysfunction or failure[7].Abnormal liver function tests, including increasing levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and lactic dehydrogenase are observed[8].Serum bilirubin level is also reported to be increased in some COVID-19 patients at the time of admission into the hospital[9].

High abnormal serum levels of aminotransferases were observed in severe illnesses rather than in trivial or mild COVID-19 illnesses[10].There are several characteristic features of high serum levels of aminotransferase enzymes.The first feature is a transient and slight increase of serum ALT and AST levels.The second feature is a dynamic pattern of liver enzymes: liver dysfunction started with an elevation of AST, slight changes of total bilirubin levels followed by increased ALT in severe patients[11], and the pattern of cholestasis is absent[8,12].Liver failure and bile duct injuries were not pathological features of COVID-19[13].Therefore, any elevated transaminase enzyme is considered an indirect expression of systemic inflammation, and there are no specific symptoms that have been linked to liver dysfunction[13].The third feature is the elevation of aminotransferase enzymes is related to race as Chinese patients less frequently had high serum aminotransferases compared with United States patients infected with COVID-19[14].These enzymes (ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase) are increased with increased disease severity.The mortality rate increased by 14.87 fold in patients with AST level (40-120 U/L), and the male gender is positively associated with elevation of AST[11].

The fourth feature is that ALT among many biochemical markers was studied as a predictor of COVID-19 severity using univariate and multivariate ordinal logistic regression models on 598 patients presenting with moderate, severe and critical illness.The results showed that patients with ALT > 50 U/L had worse severity of illness (odds ratio: 3.304, 95% confidence interval: 2.107-5.180)[15].Serum ALT level is a stronger predictor of disease severity compared with myohemoglobin, but it is weaker than cardiac troponin I or aging and the presence of high blood pressure.

Phippset al[16] categorized the acute liver injury in patients with coronavirus according to the serum levels of ALT into mild [ALT > the upper limit normal (ULN) < 2 times ULN], moderate (ALT 2-5 times the ULN) and severe (ALT > 5 times the ULN).Those authors found that 45% had mild, 21% moderate and 6.4% severe liver in a total number of 2273 patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 tests[16].The category of severe acute liver injury had significantly high inflammatory markers and a higher rate of mortality that accounted for 42%[16].In one cohort study that included 176 patients, 109 (61.9%) had evidence of liver dysfunction, and only 34 out of 109 (31.2%) had an acute liver injury (ALT and/or AST ≥ 3 ULN), which was associated with an increase in serum bilirubin, lactic dehydrogenase and C-reactive protein[17].

Figure 1 Distribution of the RNA viruses according to their strands and senses.

Another meta-analysis that included 3428 patients collected from 20 studies found that severe COVID-19 is associated with increasing levels of serum AST, ALT and bilirubin and a decreasing serum albumin level[18].This study showed no evidence of bias of all studied variables as the calculatedPvalue of the Egger’s test was nonsignificant (P> 0.1).

The fifth feature is that there is no clear association with adult respiratory stress syndrome.Most studies link acute liver injury with respiratory stress syndrome with hypoxemia and multiple organ failure.The sixth feature is they may be associated with an increased serum bilirubin level.In one study that included 11245 patients, the majority of patients presented with elevated serum bilirubin (9.7%), AST (23%), ALT (21.2%), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) (15.5%) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (4%)[19].Patients presenting with higher levels of serum bilirubin at admission indicate the progression of the disease severity[20,21].

The seventh feature is that high levels of aminotransferases are not a specific effect as other serum levels of enzymes related to the heart, kidney and muscle are also increased The eighth feature is that the high serum aminotransferases are infrequently associated with a slight increase of GGT, ALP and bilirubin[14].During admission the serum level of ALP, an index of cholangiocyte injury, is within normal limits and several factors are associated with increased serum levels of ALP including male gender, increased neutrophil count, corticosteroid use and antifungal drugs[11].The final feature is that SARS-CoV-2-infected children showed minimal or no increase in the hepatic enzymes[22].

The explanation of abnormal serum levels of ALT and AST are attributed to several factors.SARS-CoV-2 infected the pulmonary tissue causing hypoxemia.As a result of hypoxia-reoxygenation injury, Kupffer cells are activated leading to the generation of the free radicals that induce acute liver cell injury[23,24].Hypoxiade novois a form of stress that increases the activity of the sympathetic autonomic nervous system and releases adrenocorticotrophic hormone from the hypothalamus leading to acute liver injury[25].In addition, flaring of the intestinal microflora in the critical COVID-19 cases causes septic shock, which induces hypoxia of the hepatocytes and thereby hepatocellular necrosis and cholestasis[26].

Abnormal ALT and AST serum levels are also attributed to direct transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from the bowel to the liver[13,27].Inflammation and high levels of cytokines associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection causes multiple organ dysfunction.Biomarkers related to the inflammation are independent risk factors of developing acute liver injury in COVID-19.Interleukins (IL), including IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8, and soluble tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-1 are increased and played a role in multiple organ dysfunction[28].Serum C-reactive protein ≥ 20 mg/L and lymphocyte count < 1.1 × 109/mm3are significantly associated with acute live injury[7].

Chronic liver diseases also cause abnormal levels of AST and ALT.Patients with viral hepatitis are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection.Leiet al[11] reported 84 patients out of 5771 had a previous history of liver disease (4 patients had fatty liver, and 77 patients had viral hepatitis.Sarinet al[29] reported that elevation of serum bilirubin and AST/ALT ratio predicted a poor prognosis of COVID-19 (mortality rate of 43%) in patients with liver cirrhosis.On the other side, a recent meta-analysis study that included 17 studies showed that chronic liver disease had no significant effect on the poor prognosis of COVID-19[30].

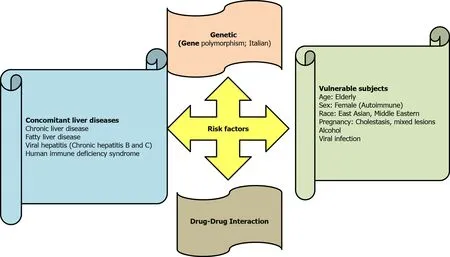

Drug-induced hepatocyte injury can also cause abnormal AST and ALT levels[31,32] (Table 1).Accordingly, drug-induced acute liver injury referred to an elevation of ALT by ≥ 5 ULN, or an elevation of ALP (in the absence of bone diseases) by ≥ 5 ULN, or the elevation of ALT by ≥ 3 ULN plus elevation of serum bilirubin level by > 2 ULN[33,34].Drug-induced liver injury is either idiosyncratic or intrinsic in nature, and several risk factors played a role in inducing liver injury (Figure 2).Antiviral agents with potential hepatotoxic effects,e.g., remdesivir, lopinavir and tocilizumab should also be considered[35-37].Acetaminophen, which might cause liver damage, is usually used in the management of COVID-19 to reduce body temperature[38,39].Azithromycin therapy is a possible cause of acute liver injury in COVID-19[40].

STRUCTURAL CHANGES IN THE LIVER DUE TO SARS-COV-2 INFECTION

Several studies clarified that SARS-CoV-2 causes nonspecific hepatic changes according to the postmortem histopathological and immunohistochemistry studies.The histopathological changes observed in the liver autopsies are[15,41] microvascular steatosis, lobular focal necrosis, cellular neutrophil, lymphocyte and monocyte infiltration in the portal area, microthrombosis and hepatic sinuses congestion.There is no evidence suggesting liver failure or development of granuloma.Electron microscopy studies showed that the endothelial cell contained coronavirus particles[42].The RNA sequence data findings and immunohistochemistry studies showed expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 receptors (ACE-2R) in the cholangiocytes but not in Kupffer cells[43], which may not be related to COVID-19.In normal liver, immunohistochemistry showed expression of ACE-2R in the bile duct lining cell but not in the hepatocytes.

COVID-19 AND METABOLIC DYSFUNCTION-ASSOCIATED FATTY LIVER DISEASE

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is the acronym of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) as NAFLD is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome, including obesity, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia[44].Therefore, COVID-19 and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease/ NAFLD can affect each other.For example, when the patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease/NAFLD are infected with SARS-CoV-2, their livers are susceptible to the harmful effects of the drugs that are clinically used in the management of the COVID-19[45-47].Also, patients with metabolic derangement are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection (e.g., diabetes mellitus)[48].Diabetic patients already have asymptomatic or symptomatic liver dysfunction or injury.

A recent study on 202 COVID-19 patients showed NAFLD is an independent risk factor for the progression of COVID-19 with an ultimately poor prognosis[49].The most common pattern of liver damage reported in the Jiet al[49] study is mild hepatocellular injury, while the ductular or mixed with hepatocellular injury was observed in 2.6%.Moreover, persistent abnormal liver function tests were observed in 33.2%, and NAFLD was independently associated with the progression of liver injury in 19.3% of COVID-19 patients.The percentage of liver injury induced by SARS-CoV-2 is related to the associated risk factor rather than the specificity of SARS-CoV-2 to attack the liver directly because ACE-2R is absent in Kupffer cells and available in 3% of the hepatocytes[43,50].

Acute liver injury was reported in 19 out of 187 (15.4%) patients in one study performed at the Seventh Hospital of Wuhan City, China.Five of the patients had a cardiac injury represented by a higher serum level of troponin[51].Zhanget al[52] summarized the studies that showed an abnormally high level of ALT, AST and GGT, which is a diagnostic marker for cholangiocyte injury, was found to be elevated in 30 of 56 patients with COVID-19 during hospitalization.The other important trigger factor of the progression of COVID-19 is drug-induced liver injury.Patients with fatty liver are at a higher risk for drug-induced liver injury compared with noninfected healthy individuals or patients without fatty liver.Some drugs might cause severe liver injury in obese patients with COVID-19, while others might induce the transition of fatty liver to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) or worsen the preexisting pathological liver lesion[53].

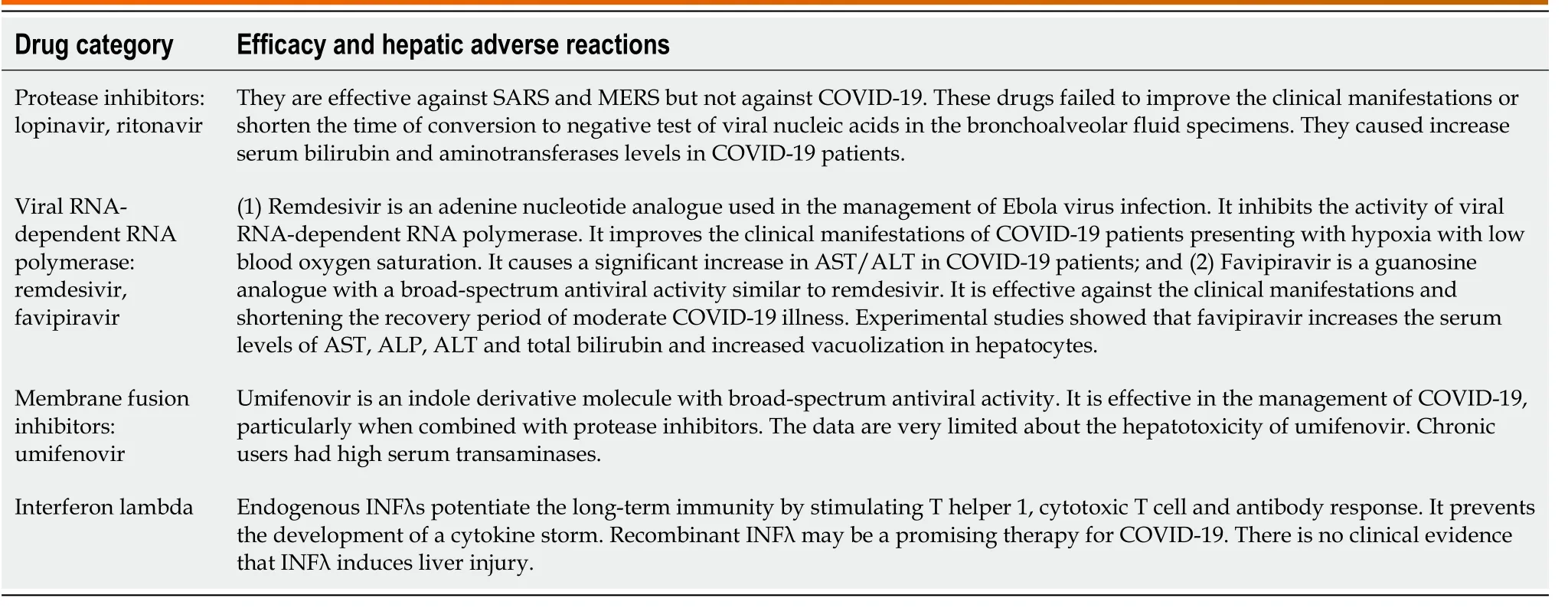

Table 1 Antiviral drugs with a promising efficacy against coronavirus disease 2019 with potential hepatotoxic effect

Figure 2 Risk factors of drug induced liver injury.

SARS-COV-2 INFECTION AGGRAVATES THE PROGRESSION OF NAFLD

Hepatocellular hypoxia is the most common explanation of hepatic metabolic derangement induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection, which leads to increases of ACE-2R in liver tissue.Tissue hypoxia is a feature of COVID-19 that is followed by an insidious and paradoxical pattern.In experimental studies, ACE-2R protein was significantly increased in the liver tissue after bile duct ligation, and the activity of ACE-2R is also increased in the human cirrhotic liver compared with a healthy liver[50].Anin vitroexperimental study showed that hypoxia increased the expression of ACE-2R in CD34 cells derived from mice subjected to hind-limb ischemia without alteration in the activity of ACE[54].Hepatocellular hypoxia also increases the expression of inducible hypoxic factors.These factors play a role in the adaptation of the endothelial cell to the hypoxia by inducing the expression of genes that promote energy metabolism of the cells[55].These factors have dual effects as HIF-1α induces inflammation by upregulating NF-kB and CD4+, CD8+ and producing proinflammatory cytokines (IL-2 and TNF-α)[56,57].

Hepatocellular hypoxia activates reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.Extensive release of cytokines (cytokines storm) play roles in recruiting the immune cells to the site of inflammation, producing vasodilation and increasing the vascular permeability and production of nitrative and oxidative free radicals, which collectively cause tissue damage[7,58-60].A nitrative stress syndrome in COVID-19 is evoked by IL-2 and IL-6[7,61], while oxidative stress syndrome was expressed in COVID-19 by IL-6 and TNFα, which increase the levels of superoxide anion in neutrophils and hydrogen peroxide[62-64].Antioxidants are useful in the management of COVID-19,e.g., vitamin C, Nrf2 activators, zinc, glutathione and N-acetylcysteine[65-67].It is important to mention that macrolides are prescribed in the management of COVID-19 because they (e.g., azithromycin and erythromycin) inhibit the generation of superoxide anion and nitric oxide[68-70].

High inflammatory response of Kupffer cells is linked to hepatocellular hypoxia.Kupffer cells are part of innate immunity that acts as scavengers and phagocytes.During COVID-19 illness, the ACE-2Rs are expressed in the circulating inflammatory macrophages and tissue macrophages, including Kupffer cells[71].Expression of these receptors may cause Kupffer cell dysfunction and lead to acute liver injury.Yuanet al[72] reported that Kupffer cells have dual actions against viral hepatitis as they cleared the hepatitis B virus (HBV)/HCV due to their phagocytic activity and at the same time produce inflammatory mediators that eventually cause immune tolerance towards HBV/HCV.

COVID-19 AND CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE

In one study including 28 patients presenting with variable chronic liver disease of different etiological factors, it was found that patients with acute on chronic liver failure showed worse outcomes, and a poor outcome was observed in patients managed with mechanical ventilation[73].The mortality rate was 33% in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis, while it accounted for 8% in patients with chronic liver disease without cirrhosis[73].The therapeutic regimen of hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, other antivirals and plasma therapy did not improve the outcome of COVID-19 in patients with chronic liver disease.Moreover, acute liver injury was reported in 14 out of 105 (13.3%) patients with coinfections of COVID-19 and viral hepatitis due to HBV.Because 4 out of 14 (28.57%) patients progressed within a short time to acute on chronic liver failure, and the study concluded that liver injury in patients with SARS-CoV-2 and chronic HBV coinfection was associated with severity and poor prognosis[74].Transient elevations of ALT, AST, GGT, ALP and bilirubin were observed in a small number of coinfected patients with COVID-19 and HBV[74].

COVID-19 AND LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Patients with liver transplantation are at risk of infection with COVID-19.Maggiet al[75] reported 16 patients managed with liver transplantation showed positive COVID-19 laboratory tests.Moreover, the mortality rate in long-term liver transplantation survivors infected with COVID-19 was 2.7% (3 out of 111 survivors), which is comparable to those without liver transplantation[76].Drug-drug interaction should be considered in the liver transplant recipient, particularly between immunosuppressive antiviral therapeutic regimens.A combination of ritonavir and protease inhibitors should be avoided, while chloroquine and remdesivir are safe[77].

ANTIVIRAL AGENTS AND LIVER INJURY

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of specific antivirals drugs are indicated in the management of severe COVID-19 or patients at risk of developing severe disease.These drugs are listed in Table 1.

Ritonavir (a protease inhibitor) can induce hepatotoxicity by laboratory evidence of elevation of aminotransferases[78,79] and clinically presented with jaundice and hepatomegaly.In addition, ritonavir can induce dyslipidemia characterized by increasing serum levels of triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, while the serum level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is decreased[78,80,81].Longterm therapy can cause dyslipidemia, which is a risk factor for developing NAFLD.Therefore protease inhibitors are unlikely to cause dyslipidemia because they are used for a short period in the management of COVID-19.

Lopinavir is another protease inhibitor used for COVID-19.It caused severe liver injury in HIV-infected patients[82].The combined therapy of ritonavir and lopinavir leads to increased toxicity of ritonavir, which presented with a higher elevation of transaminases[83].It is important to mention that protease inhibitor-induced hepatotoxicity is not related to lopinavir plasma levels but to ritonavir, which accumulated in the liver[82].A combination of lopinavir/ritonavir does not show significant improvement in the clinical and laboratory testing of COVID-19; indeed it may produce adverse reactions[84].

Remdesivir is an adenosine nucleotide analog with broad-spectrum antiviral activity used for RNA virus infection treatment[85].The most common hepatotoxicity of remdesivir in COVID-19 patients is the elevation of hepatic transaminases and multiple organ failure[86].The elevation of ALT and AST is usually reversible.

Favipiravir (6-fluoro-3-hydroxy-2-pyrazine carboxamide) is a guanosine analog with a broad-spectrum antiviral activity similar to remdesivir.It selectively inhibits the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of the virus and has a broad-spectrum activity against influenza virus and all RNA viruses that cause hemorrhagic fever[87].According to the evidence-based studies, favipiravir is effective against clinical manifestations and shortening the recovery period of moderate COVID-19 illness[88].In SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, favipiravir significantly increased the ALT and AST enzymes.Experimental studies showed that favipiravir increases the serum levels of AST, ALP, ALT and total bilirubin and increased vacuolization in hepatocytes.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have antiviral activity and have been recommended as the second therapy choice in the treatment of COVID-19[89].Limited data were available concerning the hepatotoxicity of chloroquine.

Umifenovir (Arbidol) inhibits the adsorption of the virus to the host cell and thereby prevents viral penetration of the cell.It is effective against influenza, hepatitis C and SARS-CoV-2 infections[90-92], and it has a broad therapeutic index.Chronic use of umifenovir is associated with increased transaminase levels[93].A triple combination of lopinavir, ritonavir and umifenovir is considered in the management of COVID-19 patients, but this combination induced liver damage in 50% of patients and elevated hepatic transaminases and bilirubin[94].

Recombinant or pegylated interferon lambda (INFλ) is available endogenously in four moieties and have a potent antiviral activity as they maintain the antiviral response in the pulmonary tissue[95].Synthetic (recombinant) INFλ has been effective against viral replication and obviates the development of a cytokine storm[96,97].In an experimental animal model of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the production of INFλ is decreased.Therefore, administration of synthetic recombinant INFλ can restore the endogenous INFλ and improve the immune system.

OTHER RNA VIRUSES

MERS

MERS-CoV is a viral RNA transmitted from infected camels to humans[98,99].Severe MERS-CoV infections were observed in immunocompromised patients, diabetes mellitus, renal failure and the elderly age group similar to COVID-19[100,101].Acute renal failure is the most common extrapulmonary complication in MERS-CoV patients, which accounts for 75%[102,103].Histopathological findings of the liver autopsies of patients with MERS[104,105] are similar to those observed with COVID-19, which included: (1) mild chronic lymphocytic portal inflammation; (2) mild hydropic degeneration of hepatocytes; (3) mild sinusoidal lymphocytosis; (4) no evidence of lobular or portal granuloma or fibrosis; (5) mild steatosis; and (6) occasional intralobular hemorrhage and necrosis.

Ultrastructural findings detected by electron microscopy showed MERS-CoV inside the macrophage, while SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the cytoplasm of the hepatocyte.

SARS

In SARS-CoV, the elderly age group who had the liver disease of whatever etiology showed the highest mortality rate[106].Postmortem liver autopsy studies revealed that SARS-CoV particles were present in less than 50% of liver tissue with approximately 1.6 × 106copies/g hepatic tissue[107].The characteristic features of liver injury in SARS are cellular apoptosis, increased mitotic activity, balloon degeneration of the hepatocyte, lymphocytic cell infiltration and central lobular necrosis[105,108].Infrequently, fatty degeneration was observed[109].Real-time PCR of the liver tissue was positive (similar to SARS-CoV-2), but electron microscopy did not show virus particles[107,110].

HIV and liver injury

Liver disease is the third most common cause of death in HIV patients, which is mainly due to HIV/HCV coinfections[111].Several factors are contributed to causing death in HIV patients, including metabolic syndrome, consumption of alcohol and coinfections with hepatitis C and D viruses[111].HIV patients are more likely to have fatty liver (alcoholic or nonalcoholic), which can present with any clinical manifestations.Therefore, these patients have clinical and laboratory evidence of metabolic syndrome with and without a high body mass index[112].NAFLD with HIV infection is usually present as NASH and progresses to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.The laboratory technique of elastography discloses the presence of liver fibrosis in 30%-50% of HIV patients[113,114].

The characteristic features of liver diseases in patients with HIV infections are: (1) patients with HIV infection commonly have NAFLD; (2) patients with HIV and NAFLD commonly have NASH compared with those who do not have HIV infection[115,116]; (3) an HIV-infected person with NAFLD had a lower body mass index compared with patients without HIV infection despite the similarities between the two groups in the other components of metabolic syndrome[117].Moreover, HIVinfected persons with NAFLD had a higher percentage of visceral fat compared with uninfected HIV persons[118-120]; (4) previous studies showed that antiretroviral medicines are not a cause of NAFLD, and they did not play any role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD in HIV-infected patients.HIV-infected patients managed with highly active antiretroviral therapy for 12 mo showed significant hepatotoxicity when the patients had a higher baseline serum AST level and a lower serum albumin level.Hepatotoxicity presented with elevated serum transaminases and a significantly high AST:ALT ratio[121].One retrospective study of HIV-infected patients found that concomitant viral hepatitis, duration of antiretroviral drugs and baseline data of liver enzymes can increase the risk of liver damage in HIV-infected patients[122]; (5) cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-α, are not responsible for inflammation that progressed to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis[123]; (6) liver fibrosis commonly occurred in patients with concomitant diseases,e.g., viral hepatitis C and HIV despite confounding factors, including using antiretroviral drugs and heavy alcohol consumption[124]; (7) in HIV-mono-infected patients, significantly high AST and ALT were found in 5.6% and 16.8%, respectively, while hepatic steatosis and fibrosis were found in 55.0% and 17.6%, respectively[125].Middle aged males with evidence of metabolic syndrome were more vulnerable to liver fibrosis in HIV mono-infected persons; (8) noncirrhotic portal hypertension is an uncommon complication of HIV-infection[111]; (9) hepatic granuloma and hemosiderosis and chronic active hepatitis were reported in 16%, 26% and 3%, respectively.The higher percentage of hepatic granuloma is related to intravenous drug abuse in HIV patients, while the low incidence of chronic active hepatitis is attributed to T lymphocyte depletion[126]; (10) histopathological changes of the liver showed a nonspecific or pathognomonic feature that indicated HIV infection.One study including 42 liver autopsies found that histopathological changes are usually secondary to infection, inflammation, cirrhosis and cancer[127]; and (11) HIV patients with secondary specific hepatic infections have higher serum ALP and AST compared with noninfected HIV patients[126].

Influenza A virus and liver injury

Influenza A virus is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus with eight RNA fragments.Infected patients with influenza A/Kawasaki/86 (H1N1) showed significant elevation of the serum aminotransferases indicating viral hepatitis.The significant high serum liver enzymes usually occurred after the fever had subsided, which indicates that the viral replication is not the cause but the consequent activation of the immune response[128].Rarely, using chloroquine in the prevention of influenza can cause hepatitis (elevated serum amino transaminases)[129].

H1N1 differed from the seasonal influenza infection by inducing hepatocellular injury with increased serum AST and ALT levels[130,131], while infection with H7N9 can induce hepatic hypoxia and fatty infiltration[132,133].In experimental studies using mice, influenza A virus types H1N1, H5N1 and H7N2 significantly increased serum hepatic enzymes on day 5 postinfection, and the immunohistochemistry showed positively infected hepatocytes with viruses[134].In one Korean population study, the relationship between the H1N1 2009 pandemic and acute viral hepatitis A showed a significant inverse (r= -0.597) relationship,i.e.as the prevalence of hepatitis A virus increased the prevalence of H1N1 2009 decreased.This indicates that the hepatitis A virus (positive-stranded RNA virus) damped the virulence of H1N1 2009 to attack the liver and produce exacerbation of the acute liver injury by a mechanism still unknown[135].

Viral hepatitis and liver injury

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) produces a broad spectrum of liver injury varied from mild illness (a transient elevation of serum transaminases and bilirubin) to fulminant hepatic failure, and the HAV-RNA particle was detected in the serum of the infected patient[136].Blood donor participants with previous HAV infection showed a high serum level of ALT and anti-HAV antibody, while the HVA-RNA was not detected in the serum[137].Infected patients with hepatitis E virus have low serum levels of ALT compared with HAV infection, while the serum level of GTT is high, and the patients clinically are asymptomatic[138].Infected patients with HCV may have a previous history of HBV infections, and their illness linked with liver autoimmune diseases as autoantibodies are detected in their sera[139].Most HCV are mono-infections, and a minority have HCV and HBV coinfections at a single time point with a complex pattern of virological profiles.In patients with positive hepatitis B surface antigen, the estimated prevalence of HBV/HCV is approximately 5%-20%, while in HCV positive antibody patients is 2%-10%, considering the geographical distribution factor[140].Patients with chronic hepatitis B surface antigen are liable to be infected with HDV[141].Chronic hepatitis D patients showed high viral load and transaminase levels and progressed rapidly to liver cirrhosis[142].

The relationship between serum lipids and viral hepatitis are complex.There is evidence that in the acute phase of viral hepatitis, the serum triglycerides are elevated and abnormal lipoproteins are detected in the serum[143].A low serum level of cholesterol and apolipoprotein A indicated a severe liver injury[143].NAFLD is usually associated with HBV and HCV infection, and the reason for hepatic steatosis is related to the existence of the components of metabolic syndrome (e.g., obesity, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia,etc.).Hepatic steatosis is related to the HCV-genotype 3 infection, which exerts direct metabolic effects on the liver[144].Chronic HBV and HCV infections lead to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, which carries a poor liver function compared with NASH-induced hepatocellular carcinoma[145].A case report study mentioned a 24-year-old patient presented with mild COVID-19 disease, and he experienced a cytokine storm due to coinfection with HBV leading to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and death[146].This case report highlights the worsening prognosis of superinfection with viral hepatitis in patients with RNA virus infection with coronaviruses and HIV.

Dengue virus

The clinical manifestations of the dengue virus are dengue fever, dengue with plasma leakage, dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome.The liver is the target of the dengue virus infection, and the severity of the infection is usually assessed by laboratory investigations, including serum aminotransferases, albumin and blood count in addition to abdominal ultrasound[147-152].There is evidence that the dengue virus regulates hepatic lipids in order to replicate inside hepatocytes[153], leading to an increase of aminotransferases and thrombocytopenia[154-156].Previous experimental studies showed that intracellular lipid droplets are essential for dengue virus replication, and postmortem studies confirmed that lipid vesicles in the liver autopsies are used for dengue virus replication[151,157].

NAFLD is a feature of dengue virus infection, whether related to the clinical category of dengue with or without plasma leakage[158].A high serum ALT level is a characteristic feature of dengue virus infection during the febrile period of any clinical category[158].Patients with dengue hemorrhagic fever complicated with multiple organ failure showed elevation of both ALT and AST, while those patients without multiple organ failure did not show elevation of the serum AST level[159].Fatty infiltration in dengue-infected patients with plasma leakage indicating dengue severity as hemoconcentration and thrombocytopenia are commonly reported in those patients[158].Postmortem histopathology studies of liver autopsies of dengue-infected patients showed sinusoid congestion, hepatocytes necrosis, fatty infiltration or steatosis[160].

Ebola virus and liver injury

Ebola virus disease (formerly called Ebola hemorrhagic disease) is a disease caused by the RNA virus transmitted from animals (e.g., bats) to humans and spreading through human-to-human transmission.It is a fatal disease complicated with multiple organ dysfunction like COVID-19[161].The fatality rate of Ebola virus disease is attributed to the exaggeration of the immune response leading to extensive production of cytokines (cytokine storm) like COVID-19[162].Hepatomegaly and hepatocellular necrosis are the characteristic features of liver lesions induced by the Ebola virus.Bradfuteet al[163] demonstrated that Ebola virus induced-hepatocyte apoptosis is linked to the progression of the disease, while lymphocyte apoptosis is not involved in the progression of the disease.Patients who recovered from Ebola virus disease may complain from recurrent hepatitis in the future[164,165].

Lassa virus and liver injury

Lassa virus is an old-world arenavirus that is transmitted from small animals,e.g., rat, to humans.In 1969, the virus was first described in Nigeria, and it caused fatal hemorrhagic fever.Lassa fever can cause hepatitis, which was not the cause of death or progressed to liver failure[166].Lassa virus-induced liver injury is acute active hepatitis without lymphocytic infiltration, which progresses to more hepatocyte necrosis or recovery.Gross and histopathological findings of liver autopsies are fatty metamorphoses but no evidence of fatty infiltration like COVID-19 and hepatocellular necrosis with eosinophilic, not lymphocytic, infiltration[167].In an experimental hamster model, Pirital virus produced similar changes observed in human Lassa fever, including elevation of serum levels of hepatic transaminases combined with hepatocellular necrosis[168].

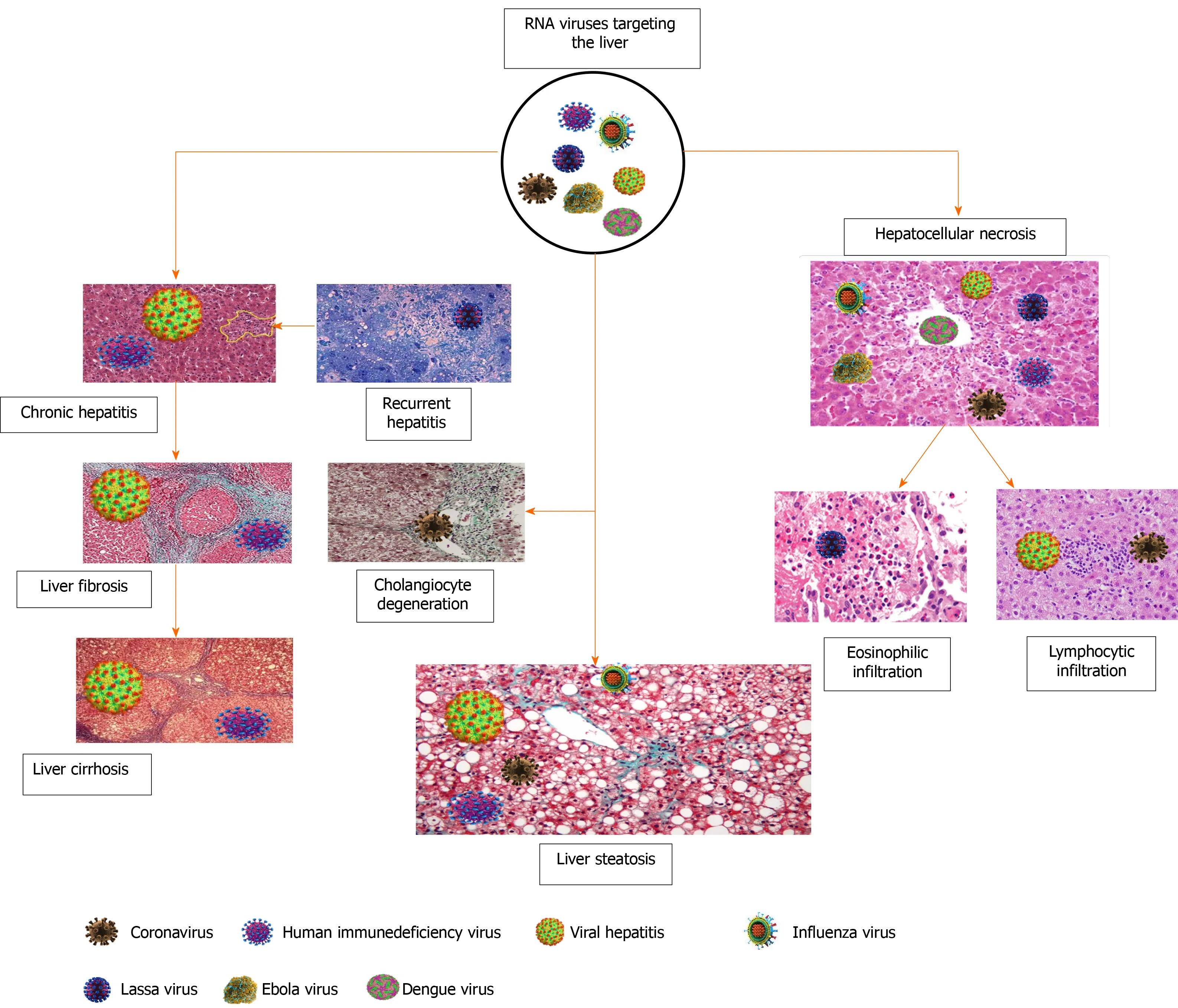

ROLE OF RNA VIRUSES IN LIVER FIBROSIS

Liver fibrosis is a term for a progressive accumulation of the extracellular matrix leading to disruption of the normal liver architecture[169,170].This condition develops in response to viral infection, metabolic disorders, chemicals, heavy alcohol consumption and autoimmune diseases[171,172].At the molecular level, HBV through HBV X protein, which is expressed during infection, will activate the hepatic stellate cells[173] and induce fibrosis, while hepatitis delta virus is involved in the progression of existing fibrosis[174].Hepatitis delta virus antigen (notably the large isoform) activates the HBV X protein to mediate and enhance the signals that induce liver fibrosis.On the other hand, proteins derived from HCV arede novoprofibrogenic [175].This indicates that HCV-induced liver fibrosis mechanisms differed from that mentioned with HBV or HCV.Moreover, some authors believe in the role of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and iron accumulation in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis[176-178].HIV is not fibrogenicper se, but it can accelerate existing liver fibrosis induced by HBV or HCV[179].Mono-HIV infected persons do not significantly show liver fibrosis compared with those presenting with coinfections with HBV or HCV[180].Figure 3 summarizes the liver injury induced by RNA viruses and shows that the outcome event of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis is not a feature of COVID-19.

CONCLUSION

Acute liver injury is an asymptomatic manifestation of COVID-19 represented by a transient and reversible increase of liver enzymes.Microvascular steatosis, lobular focal necrosis, immune cell infiltration in the portal area and microthrombosis are postmortem findings of patients with multiple organ dysfunction.The liver injury produced by SARS-CoV-2 infection has completely differed from the corresponding liver damage induced by other RNA viruses.Risk factors of liver injury in COVID-19 patients are age, race, concomitant liver diseases and evidence of metabolic derangement.The chronicity of liver injury is still unknown, and further prospective studies are recommended to clarify the role of SARS-CoV-2 in inducing fibrosis and fatty liver.

Figure 3 Liver injury categories induced by RNA viruses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author expresses his gratitude to Professor Dr.Ismail I.Latif, the Dean of the College of Medicine, University of Diyala for his kind support, and to Assistant Lecturer Sura K.Khubala at University of Imam Ja’afar Sadiq for the technical support.

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2021年2期

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2021年2期

- World Journal of Meta-Analysis的其它文章

- Effect of resistance exercise on insulin sensitivity of skeletal muscle

- Ankle injuries in athletes: A review of the literature

- Viral hepatitis: A brief introduction, review of management,advances and challenges

- Metabolic and biological changes in children with obesity and diabetes

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular concerns: The time for hepatologist and cardiologist close collaboration

- Therapeutic applications of dental pulp stem cells in regenerating dental, periodontal and oral-related structures