Malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis: A case report and literature review

Jun-Chen Chen, Dong-Zhou Zhuang, Cheng Luo, Wei-Qiang Chen

Jun-Chen Chen, Dong-Zhou Zhuang, Cheng Luo, Wei-Qiang Chen, Department of Neurosurgery,The First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou 515041,Guangdong Province, China

Abstract BACKGROUND Malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis is a very rare disease. Combining our case with 16 previously reported cases identified from a PubMed search, an analysis of 17 cases of malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma was conducted. This literature review aimed to provide information on clinical manifestations, radiographic and histopathological features, and treatment strategies of this condition.CASE SUMMARY A 60-year-old man was admitted with a progressive headache and enlarging scalp mass lasting for 3 mo. Radiographic images revealed a left temporal biconvexshaped epidural mass and multiple lytic lesions. The patient underwent a left temporal craniotomy for resection of the temporal tumor. Histopathological analysis led to identification of the mass as malignant pheochromocytoma. The patient’s symptoms were alleviated at the postoperative 3-mo clinical follow-up.However, metastatic pheochromocytoma lesions were found on the right 6th rib and the 6th to 9th thoracic vertebrae on a 1-year clinical follow-up computed tomography scan.CONCLUSION Magnetic resonance spectroscopy and histopathological examination are necessary to make an accurate differential diagnosis between malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma and meningioma. Surgery is regarded as the first choice of treatment.

Key Words: Malignant pheochromocytoma; Catecholamine-secreting; Cerebral metastasis;Skull metastasis; Meningioma; Magnetic resonance spectroscopy; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Pheochromocytomas are rare catecholamine-secreting neuroendocrine tumors that originate from the chromaffin cells of the sympathoadrenal system[1-5]. The incidence of pheochromocytoma in the general population ranges from 0.0002% to 0.0008%[3]. Most pheochromocytomas are located in the adrenal gland due to this location having the largest collection of chromaffin cells[2,3]. Similar to pheochromocytomas, paragangliomas are catecholamine-secreting tumors that arise from extra-adrenal sites along with tumors of the sympathetic nervous system and/or pheochromocytomas(such as the neck, mediastinum, abdomen, and pelvis)[3,6]. Accumulating evidence suggests that the possible mechanism of pheochromocytomas is related with germline mutations in known susceptibility genes, such asNF1andVHL[7]. In the case of malignant pheochromocytomas, metastases are present in aberrant endocrine tissue without chromaffin cells[3,8]. In general, approximately 2%-26% of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are malignant[9]. These metastases are usually located in the bones, liver, lungs, kidneys, and lymph nodes[3,8].

However, malignant pheochromocytomas with cerebral and skull metastasis are even more uncommon. This report describes a case of malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis and reviews 16 previously documented cases to gain a better understanding of malignant pheochromocytomas with cerebral and skull metastasis, including the mechanisms of pathogenesis, histopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics, clinical manifestations, radiographic features,and treatments. Furthermore, we also compared malignant pheochromocytoma and meningioma. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College (B-2020-222).

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 60-year-old man was admitted with a progressive headache and enlarging scalp mass.

History of present illness

The patient’s symptoms started 3 mo ago with a progressive headache and enlarging scalp mass.

History of past illness

The patient’s family reported that he had a history of left adrenal pheochromocytoma,which presented as paroxysmal hypertension and was finally surgically removed at another hospital 5 years prior. The patient also had a 15-year history of gout.

Personal and family history

No pertinent family history was identified, including von Hippel-Lindau syndrome,multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, and neurofibromatosis type 1.

Physical examination

The blood pressure was 138/86 mmHg, and the heart rate was 83 beats per minute.The neurological and physical examinations revealed a left temporal scalp mass (6.0 cm × 4.0 cm × 2.0 cm), which was hard and fixed. Other physical findings were unremarkable.

Laboratory examinations

Routine laboratory tests and preoperative hemodynamic and cardiovascular assessments were ordered. The 24-h urinary vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) and metanephrine levels were within normal limits.

Imaging examinations

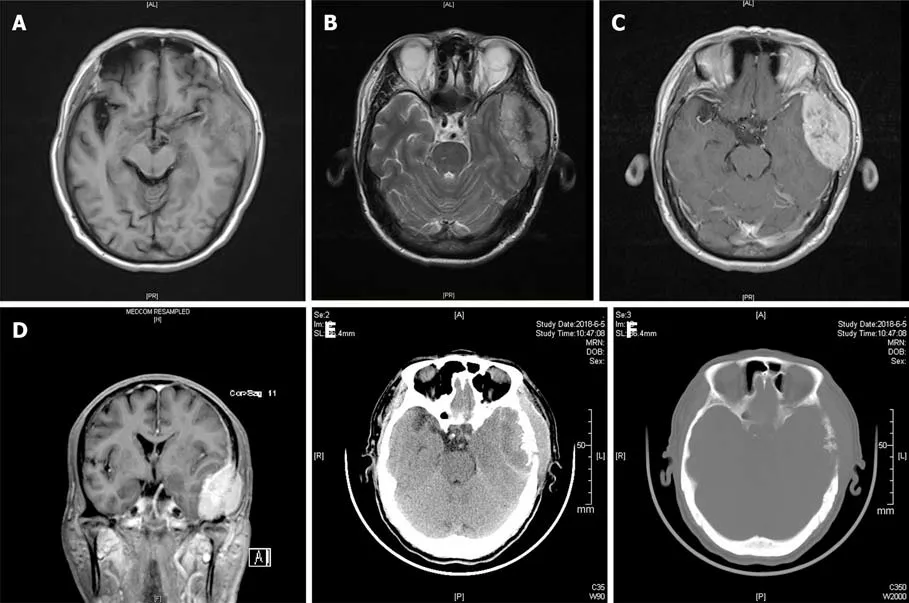

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a biconvex-shaped epidural mass (6.0 cm× 4.0 cm × 3.4 cm) that compressed the left temporal lobe with extracranial and intracranial extension (Figure 1A-D). The mass showed mixed hypo- and hyperintensity on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) and T2-weighted imaging (T2WI).After gadolinium injection, the homogeneous enhancement of a well-defined lesion with a dural tail sign was observed. Cranial computed tomography (CT) demonstrated multiple lytic lesions in the left temporal bone (Figure 1E and F). The abdominal CT findings were unremarkable, with adrenal lesions. Based on the above findings, our differential diagnosis of this mass lesion included malignant meningioma, skull neoplasm, and even rare malignant pheochromocytoma.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis.

TREATMENT

The risk of surgical intervention and general anesthesia was high because of the size and abundant blood supply of the tumor. In consultation with the anesthesiologist,adequate preoperative preparations were proposed: Standard blood pressure control(below 160/90 mmHg) and no S-T segment changes or T-wave inversions on electrocardiography. Adequate red blood cells and frozen plasma preparations were also recommended.

The patient underwent a left temporal craniotomy for resection of the temporal tumor. After making an incision in the skin, we found that the tumor had invaded the musculi temporalis. The mass was tightly attached to and infiltrating the underlying bone. Bony decompression (approximately 7 cm × 7 cm) was achieved to completely resect the lesion. After decompression, tumor tissue was found in the epidural space with a blood supply from the underlying dura. Direct tumor manipulation and coagulation and debulking of the supplying blood vessels resulted in significant alterations in blood pressure (70-230/40-110 mmHg). Four units of red blood cells and 400 mL of fresh-frozen plasma were transfused to counteract the blood loss during the operation. The tumor and surrounding dura were completely resected, and no remaining mass was seen in the subdural space. Then, dural grafting was performed with artificial dura. Finally, the outer layers were sutured step-by-step to achieve anatomical reduction. After surgery, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and placed under close surveillance.

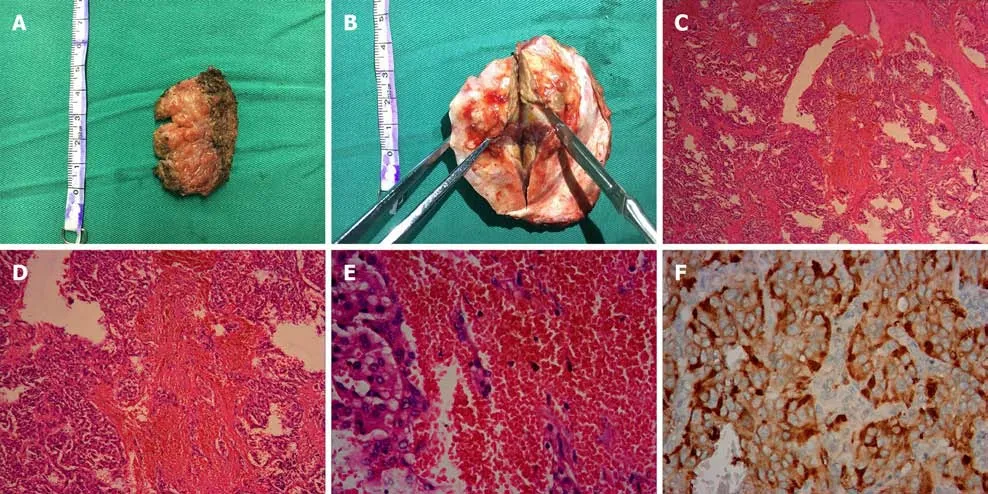

Histopathological analysis led to identification of the mass as malignant pheochromocytoma. Grossly, the surgical specimen was separated into the extracranial part (the musculi temporalis) and the intracranial part (the epidural mass with adhered temporal bone) (Figure 2A and B). Both of these parts were grayish-yellow in color on the cut section. Microscopically, the specimens revealed nested and trabecular arrangements of neoplastic cells surrounded by a labyrinth of capillaries. Granular cytoplasm and round-to-oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli were noted in the neoplastic cells. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed strong, diffuse immunoreactivity for vimentin, Syn, and CgA but negative nuclear and cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for S-100, EMA, and CD10. The P53 labeling index was approximately 1%, while the Ki-67 labeling index was 20% (Figure 2C-F).

Figure 1 Radiographic images of the presenting case. A: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) T1-weighted imaging showed an isointense left temporal lobe mass; B: MRI T2-weighted imaging showed a mixed hypointense and hyperintense left temporal lobe mass; C: Homogeneous enhancement of well-defined lesion was showed on axis MRI after intravenous contrast material; D: Coronal MRI showed the left temporal lobe mass after intravenous contrast material; E: Unenhanced computed tomography (CT) scan indicated the left temporal lobe mass; F: Multiple lytic lesion of the left temporal bone was noted on CT scan.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Neither fluctuating blood pressure nor cardiac dysfunction parameters were noted in the postoperative course. One week after the operation, the patient’s headache was alleviated. He did not receive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or targeted therapy.

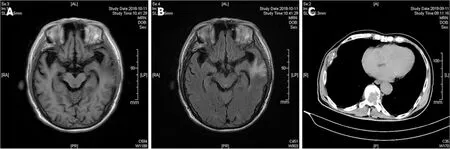

Based on the postoperative 3-mo clinical follow-up, the patient had a favorable outcome, reporting that symptoms were diminished, with normalized blood pressure and catecholamine values and no relapse of the mass on follow-up cranial MRI examinations (Figure 3A and B). However, metastatic pheochromocytoma lesions were found on the right 6thrib and the 6thto 9ththoracic vertebrae on a 1-year clinical follow-up CT scan (Figure 3C).

DISCUSSION

Preoperative clinical manifestations

Malignant pheochromocytomas with cerebral and skull metastasis have preoperative clinical manifestations that vary among patients. According to previous studies,headache, vomiting, and cognitive deterioration are the most frequent symptoms in these patients and are related to the mass effect on the brain parenchyma. Another important symptom is hypertension (including paroxysmal hypertension), which does coincide well with the features of typical pheochromocytomas because of the excess catecholamine secretion. In contrast to the above symptoms of functioning tumors,nonfunctioning malignant pheochromocytomas with cerebral and skull metastasis are usually clinically silent or just painless scalp masses. Some cases were found due to regular radiographic surveillance[16,23]. Silent clinical manifestations may delay the accurate diagnosis, and some patients may develop symptoms because of the metastatic growth of the tumor, which may make subsequent therapy a challenge[3].Typically, the diagnosis of pheochromocytomas should be based on the findings of different examinations, including clinical, laboratory, and imaging examinations[3].Preoperative symptoms might be significant signs of deterioration in those with a previous history of pheochromocytoma. We recommend regular radiographic surveillance for pheochromocytoma patients so that malignant metastatic growth can be detected early.

Figure 2 Histopathological appearances of the left temporal lobe mass. A: The extracranial part (the musculi temporalis) of the gross surgical specimen; B: The intracranial part (the epidural mass with adhered temporal bone) is showed; C: Neoplastic cells arranged in a nested and trabecular fashion and surrounded by a labyrinth of capillaries are demonstrated (hematoxylin and eosin, × 40); D: Hematoxylin and eosin, × 100; E: Hematoxylin and eosin, × 400; F:Immunohistochemical analysis revealed strong diffuse immunoreactivity for CgA.

Figure 3 Follow-up radiographic images of the presenting case. A: No relapse of mass was showed on 3-mo follow-up magnetic resonance imaging(MRI) T1-weighted imaging; B: Cerebral edema was presented on the left temporal lobe on 3-mo follow-up MRI; C: Metastasis of pheochromocytoma was noted on the rib and vertebra on 1-year clinic follow-up computed tomography.

Malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma vs meningioma

We considered meningioma as a differential diagnosis of malignant pheochromocytoma because they share comparable complaints, clinical manifestations, and imaging features, as observed in our case. Previous studies have indicated that malignant pheochromocytoma has a strong relationship with meningioma in terms of genetic origin. Pheochromocytoma and meningioma originate from a common embryological tissue - the neural crest[16,17]. The cells of the meninges, the adrenal medulla, and paraganglionic tissue are derived from the neural crest. This feature can be strengthened by evidence of "neurocristopathies" (disorders of the neural crest). For example, pheochromocytoma may exist in von Hippel-Lindau disease, and meningioma may exist in neurofibromatosis type 2. Both of these diseases are“neurocristopathies”. In addition, some previous cases have reported the coexistence of pheochromocytoma and meningioma in the brain[26,27]. Furthermore, Gabrielet al[28]reported a rare case in which a patient with supratentorial meningioma and episodic hypertension associated with excess urinary VMA excretion underwent excision of the tumor. The level of VMA became normal after the operation, and they concluded that meningioma may mimic features of pheochromocytoma. These results reinforce the fact that there are many similarities between pheochromocytoma and meningioma.

Some previous studies have pointed out that pheochromocytoma is very similar to meningioma on chromosomal analysis. Mutations in the long arm of chromosome 22 can be found in some pheochromocytoma and neurofibromatosis type 2 (with meningioma and acoustic neurinoma) patients[16,29,30]. It seems that the loss of heterozygosity on the long arm of chromosome 22 is the most likely candidate locus for the combination of pheochromocytoma and meningioma. However, compared to the comparative genomic hybridization of other types of malignant pheochromocytoma, malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral metastasis has a special loss at 18q, which is believed to be the key genomic alteration[19].

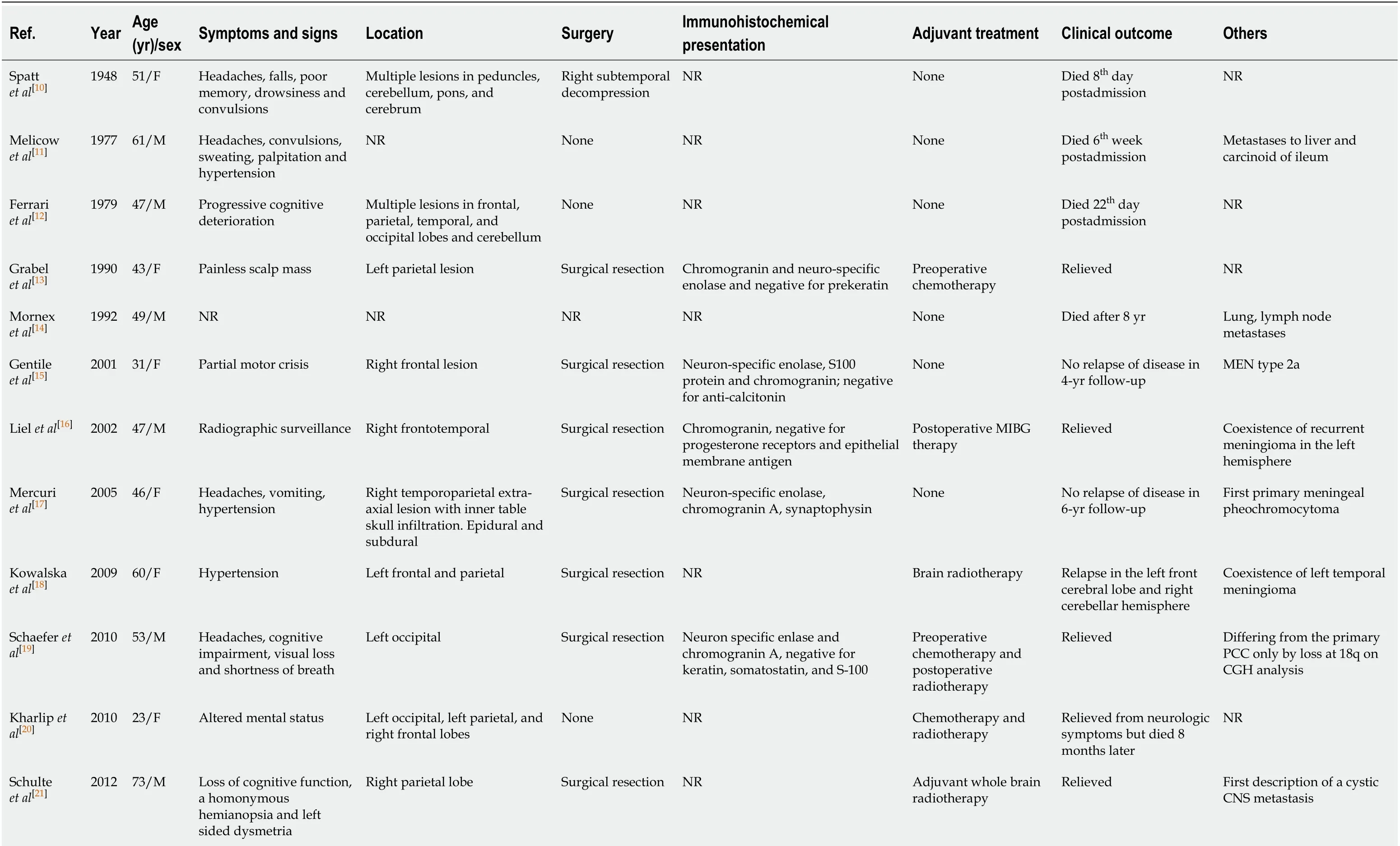

To our knowledge, two previous cases of malignant pheochromocytoma with skull metastasis have been reported[15,16]. After a review of cases of malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral metastasis in the literature, we found tumor infiltration of the skull in most of these cases, which also occurred in our case. It is difficult to identify whether the malignant pheochromocytoma metastasizes to the brain or the skull because both are involved in these cases (Table 1). Accordingly, we hypothesized that pheochromocytoma metastasis is restricted to tissues with a common embryological origin. In the study by Jianget al[31], they illustrated that in the mammalian skull vault, the frontal bones are neural crest-derived and the parietal bones are mesodermal in origin. They also suggested that a layer of neural crest cells forms the meningeal covering of the cerebral hemisphere. This fact can explain why osseous cranial metastasis is also associated with intracranial extension. We believe that the metastasis in our case was restricted to cerebral metastasis because the lesions share a common embryological tissue: The parietal bone and meninges are derived from the neural crest. Pure skull metastasis is rare because the meninges cover almost all of the cerebral hemispheres and are next to the inner layer of the skull bones.Schulteet al[21]reported the first case of cystic central nervous system (CNS) metastasis in the right parietal lobe of a patient with malignant pheochromocytoma, which might be a case of metastasis to the meninges.

Malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma and meningioma have similar clinical manifestations. As the course and treatment of these diseases can vary, it is important to make an accurate diagnosis as soon as possible. It might be difficult to make an accurate diagnosis on CT or even T1WI and T2WI. However, MRI spectroscopy (MRS)may provide some important clues for making a differential diagnosis of malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma and meningioma. Meningioma often shows a high alanine and methionine signal on MRS, while a high lipid signal suggests meningeal metastasis[25]. Despite the diagnostic utility of MRS, we place special emphasis on the importance of histopathological examination to make an accurate diagnosis.

Treatment options

Surgery: According to the literature review, 12 of 17 patients underwent surgical resection for the treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis. Decompressive surgery was performed in only one patient for relief of the increased intracranial pressure (Table 1). Good clinical outcomes were found in 9 of 12 patients who underwent surgical resection on follow-up. It seems that surgical resection is the primary curative treatment for those patients[3,32-34]. Most metastatic cerebral and skull lesions of malignant pheochromocytoma are superficial to the cerebral hemispheres and easier to remove than tumors in deep parts of the central nervous system. First, complete surgical resection can reduce anatomical complications, such as headaches due to mass effects and cerebral edema[3,32,34]. Second,removal of the tumor can reduce or even abolish excess catecholamine secretion such that the normalization of blood pressure and relief of hormonal manifestations can be achieved[3,32,34]. Third, the opportunity for distant metastasis can be reduced[34]. Last but not least, surgical resection reduces the tumor burden and is beneficial for subsequent radiotherapy because fewer doses of irradiation are needed, which thus reduced the potential for complications of radiation (i.e., bone marrow suppression).

Adequate preoperative management is key to successful surgical resection.Consistent with benign pheochromocytoma, in malignant pheochromocytoma,patients need to achieve good control of hypertension using alpha- and beta-adrenergic blockers. In addition, an appropriate fluid and electrolyte balance is needed[3,32]. The introduction of opioids, antiemetics, neuromuscular blockage, or sympathomimetics and tumor manipulation could lead to a massive intraoperative outpouring of catecholamine, accompanied by fluctuating blood pressure and arrhythmia[34]. Endovascular embolization treatment may be beneficial for surgical resection[22]. It might reduce the blood loss and excess release of catecholamine during the operation. These adequate preoperative managements have a good impact on the process of anesthesia and surgery.

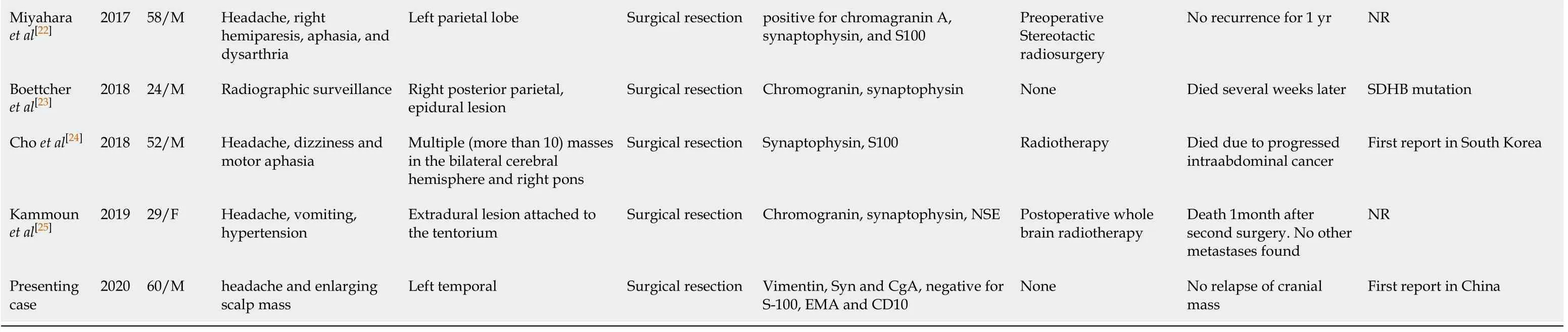

Table 1 Summary of malignant pheochromocytomas with cerebral and/or skull metastasis

CGH: Comparative genomic hybridization; CNS: Central nervous system; EMA: Epithelial membrane antigen; F: Female; M: Male; MEN: Multiple endocrine neoplasia; NR: No reported; PCC: Pheochromocytoma; SDHB: Succinate dehydrogenase subunit B.

Radiotherapy:Based on our review of case reports on PubMed, 7 of 17 patients underwent radiotherapy or stereotactic radiosurgery[14,18-22,24,25]. The question of whether radiotherapy is beneficial to patients is still open. Kharlipet al[20]reported success in a case in which the cerebral metastasis was nearly eliminated by radiotherapy, and the patient remained free of neurological symptoms without surgery. They suggested that radiotherapy at a dose of 3500 cGy to 4000 cGy should be a treatment option recommended for patients with cerebral metastatic lesions of pheochromocytoma. In the case presented by Choet al[24], postoperative radiotherapy partially decreased the size of multiple metastatic cerebral lesions on follow-up MRI[24]. Contrary to these two cases, radiotherapy and stereotactic radiosurgery showed poor effects in some other cases[22,25].131I-MIBG therapy has been mentioned in two cases as a palliative treatment for metastatic cerebral pheochromocytoma[21,26]. Further studies are needed to determine the efficacy of external irradiation in cerebral metastatic patients.

Chemotherapy:Chemotherapy is considered a choice for malignant pheochromocytoma patients who are not suitable for surgery. The cyclophosphamide, vincristine,and dacarbazine regimen is usually used for neuroblastoma patients but is also used in malignant pheochromocytoma patients because neuroblastoma and pheochromocytoma share a common embryological tissue-the neural crest[3,34]. Only 3 of 17 patients had received adjuvant chemotherapy[13,19,20]. There is still a lack of systematic studies evaluating the value of chemotherapy because of the rarity of this pathology.

CONCLUSION

Malignant pheochromocytoma with cerebral and skull metastasis is extremely rare. It is noteworthy that malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma shares similar clinical manifestations with meningioma because both originate from a common embryological tissue-the neural crest. The different features on MRS and histopathological examination might help to make an accurate diagnosis. Although radiotherapy was effective in two cases, the summary of 17 cases indicates that surgery is the first treatment choice for malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma.Further studies are needed to gain better knowledge on the origin and treatment of malignant cerebral pheochromocytoma.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participant of this study and all the staff who participated the clinical management of the patient.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2021年12期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2021年12期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Standardization of critical care management of non-critically ill patients with COVID-19

- Mediastinal lymphadenopathy in COVID-19: A review of literature

- Polycystic ovary syndrome: Pathways and mechanisms for possible increased susceptibility to COVID-19

- Circulating tumor cells with epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers as potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of lung cancer

- Clinicopathological features of superficial CD34-positive fibroblastic tumor

- Application of a rapid exchange extension catheter technique in type B2/C nonocclusive coronary intervention via a transradial approach