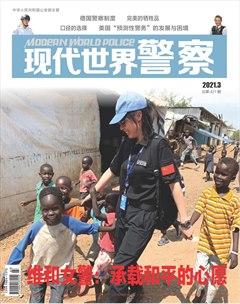

Peacekeeping in the Pandemic

By Li Fang

Mission to Cyprus amid COVID-19

It was late night on March 5, 2020. The departure hall in Shanghai Pudong Airport was almost empty, contrasting sharply with the hustle and bustle in former times. I did not have to wait in long queues for check-in or security check, for mine was the only flight still operating that night—the Munich-bound Boeing 747 waiting alone at the parking apron—while all other flights were cancelled. After waving farewell to my family, I boarded the airplane, only to find more flight attendants than passengers. After all, China at the time was going through severe lockdown. When I transited in Munich hours later, I found the airport as busy as ever. At twilight mountains loomed on the horizon and I arrived in Cyprus, an island country east of the Mediterranean Sea. There I started my second peacekeeping mission.

Straddling the three continents of Europe, Asia and Africa, Cyprus, the “bridgehead to Europe” is of strategic importance. Cyprus gained its independence from United Kingdom in 1960. An inter-communal clash occurred in 1963. The following year witnessed the establishment of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (hereafter UNFICYP) in accordance with Resolution 186. In 1974, the Greek Cypriots mounted a coup détat, inducing a military intervention by Turkey. Later, the country was in effect ruled by two forces, with the northern regions controlled by Turkish Cypriots and the southern regions by Greek Cypriots. The UNFICYP was supposed to prevent further conflicts between Greek and Turkish Cypriot forces, maintain and re-establish law and order, restore political stability, supervise the ceasefire lines, safeguard civil activities in the buffer zone, provide humanitarian assistance, and support the Secretary-General and his Special Representatives political mediations in the peace effort.

UNFICYP consists of over 900 members divided into the civilian, military, and police components. It is also the only UN peacekeeping mission with all three components led by females. The Mission has been headed by Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) Elizabeth Spehar of Canada since June 2016. The former Force Commander of UNFICYP was Major General Cheryl Pearce of Australia, whose term ended in January, 2021.

As UNFICYPs Chief Superintendent, I work alongside 69 police officers from 16 countries including Ireland, Russia, Ukraine, India and China. My responsibilities include maintaining law and order in the buffer zone, supervising border checkpoints between Southern and Northern Cyprus, preventing and reporting on illegal activities, maintaining communications with the police forces in Southern and Northern Cyprus and coordinating police-related affairs, supervising and promoting regular civil activities, and assisting the parties in building mutual trust to reach a peaceful settlement of the conflicts.

Before my mission to Cyprus, I had served as a police officer at the Putuo Branch of the Shanghai Municipal Public Security Bureau for 26 years. I applied to the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPO) for the Chief Superintendent position in UNFICYP upon the recommendation of the International Cooperation Bureau of Chinas Public Security Ministry, and took on the assignment after passing several written examinations and interviews.

The year 2020 marked the 75th anniversary of the founding of the UN and the 20th anniversary of Chinese polices participation in peacekeeping operations. For me personally, the year was also extraordinary as it marked my second UN peacekeeping assignment following the one to Haiti in 2008.

From Haiti to Cyprus

It feels both familiar and different to wear the blue beret again after 12 years. On my first UN peacekeeping assignment, I was deployed to the Caribbean island country of Haiti alongside 17 colleagues from Shanghai. Like UNFICYP, the former United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) also had the civilian, military, and police components, with the police component consisting of over 1,000 officers from 39 countries serving as individual police officers (IPOs) or in riot police units. My service in MINUSTAH, as in any other UN peacekeeping mission, was characterized by harsh living conditions, constant instability, and frequent outbreaks of violent conflicts; moreover, MINUSTAH also set itself apart by being the only UN peacekeeping mission where personnel was required to carry firearms on a 24-hour basis. I remember carrying my Beretta 92 pistol when shopping for groceries at supermarkets and tucking it under my pillow before sleep.

At that time, the capital of Haiti Port-Au-Prince was divided into red, yellow and green zones, and no personnel from MINUSTAH were allowed to enter the red zone unless escorted by peacekeepers. Evacuation was the first lesson we were taught at orientation: according to the mission mandate, each member of the peacekeeping personnel should prepare a 15 kg evacuation bag containing personal identification documents, water, food and other supplies. In the case of a serious emergency, everyone must retreat with their evacuation bags to the nearest assembly point within 30 minutes and await evacuation there. I myself witnessed to several life-threatening emergencies. For example, during my deployment as police reinforcement to supervise the election of Parliament, I encountered a fully armed local gang who broke into polling stations to steal the votes. Sometimes the dangerous situation could be further complicated by a natural disaster, which was commonplace in the Caribbean island country. For instance, my colleagues once got stuck in a great flood for over 40 hours when assisting local police in keeping prisoners in custody. Fortunately, they braved it out by keeping all the prisoners under control before helicopters came to their rescue.

In Haiti, the job of civilian police officers was primarily to rebuild the local police force from scratch, which ranged from the construction of police academies, police stations and other facilities, to training local officers on basic police skills and re-establishing procedures for law enforcement.

My second mission differed: I changed from a personnel officer to the Head of the Police Component of UNFICYP in charge of all UNPOL activities. This mission, in fact, was completely different from my previous one. On the one hand, social unrest and poor logistics are the least of our problems here, with UNFICYP being the earliest and longest-standing UN peacekeeping operation, and the Northern and Southern Cyprus governments functioning in full capacity with a competent, well-equipped, and well-trained police force in place. The mission of UNFICYPs police component is mainly to watch over the buffer zone that extends 180 kilometers from east to west across the country, oversee the implementation of the ceasefire agreement between both parties, and build up mutual trust to put the country on a political path towards lasting peace. On the other hand, service in UNFICYP poses a unique set of challenges to us. As a traditionally European-dominated peacekeeping mission, UNFICYP tops all UN peacekeeping missions in the percentage of European police officers, with only a small number of officers deployed from China, India, Pakistan, and other Asian countries. Furthermore, the police component of UNFICYP is demanding for its IPOs. For one thing, IPOs here have to be fluent in oral and written English, as our job often involves independently coordinating between conflicting parties in the buffer zone and filing work reports afterwards on every case we have handled for review. Furthermore, IPOs should also be extremely tactful and politically shrewd when going about our work, as any mishandled case could give rise to complaints from the local community or even from top officials of both parties. By and large, a UNPOL officer is expected to be a negotiator, a mediator, as well as a diplomat.

Service in a UN peacekeeping operation could avail us of opportunities of intercultural exchanges, but sometimes it could also lead to miscommunication. For instance, I once overheard a European female officer advanced in years, complaining about an Asian colleague who claimed to respect her for her age. I explained to her that respect for the elderly was a tradition in the East and hoped that she could understand. The clash between Eastern and Western cultures is also revealed in the different responses to COVID-19. It was on March 9, the third day after my arrival, that the first COVID-19 case was confirmed in Southern Cyprus. At that time, I was still undergoing a 14-day quarantine and could only work remotely. I immediately discussed the matter with my team and formulated several preventive measures, including compulsory mask-wearing, based on the experience and best practices in China. However, my recommendations were rejected on the grounds that face covering would violate the peacekeepers personal appearance policies. As it turns out, the leadership later agreed that wearing masks should be made mandatory to contain the rapid spread of the epidemic. Nevertheless, from our discussions afterwards, we came to realize that mask wearing meant different things in different cultures. For people in the East, wearing a mask is an act of respect for others as it would prevent them from possible infection; whereas the Westerners believe that not wearing a mask shows that one is healthy and would not pose a health risk to others.

The dispute over the mask-wearing policy is but one of many examples of culture clashes that we experienced in our mission. Despite the differences, we managed to understand each other and maintain mutual respect through constant communication. This is also one of the great advantages of working in the UN, where people communicate with each other thoroughly and equally until all parties come to a solution acceptable to everyone.

In my two missions as a peacekeeper, I personally played different roles: first as a personnel officer and second as the Head of the Police Component. The short span of twelve years, however, seems to indicate the change of Chinas roles from a participant to a leader in peacekeeping. It is also a testimony of Chinas determination to play a growing part in the UNs peacekeeping mission.

(Translated by Shao He)