藏书文化的历史沿革

中国私家藏书可追溯至春秋时期,古人把文字写在竹木条(称为“简”)上,编成简册束之楼阁。秦始皇统一六国后,收缴天下藏书并设置专门的藏书机构。至汉代,中国藏书制度逐步确立,刘邦开国之初,修建了石渠阁、天禄阁、麒麟阁三座国家藏书楼,收藏从秦丞相府、御史府收集的书籍。

在管理上,西汉时由御史中臣、太常、太史等兼管图书。从东汉桓帝时开始,国家藏书设置了专门管理机构——秘书监,职官有兰台令史、东观郎、校书郎以及秘书监等。从此,藏书的管理工作走向正规化。

两汉统治者比较重视文化。鉴于国家藏书甚少,历代帝王从民间各地进行了多次征书与献书。特别是汉武帝时期,从“罢黜百家,独尊儒术”实现思想文化的大一统出发,于公元前124年开始,开献书之路,大集天下之书。这一措施得到了河间献王刘德等人的响应,不少在秦始皇焚书时埋藏于地窖、墙壁、深山里的书简被发掘出来,纷纷献上朝廷。一时国家藏书大量增加,“积如丘山”。

此后私家藏书经历了几个不同的发展阶段。

魏晋南北朝、隋唐时期,是中国藏书文化的大发展时期。据文献记载,隋唐藏书过万卷者达20余人,这一时期我国的学术文化迅速发展,经史子集四部典籍以及佛道经典,比汉代大大增加。造纸技术和材料也进一步得到改进,纸得以普遍运用,从而促进了私人藏书的快速发展,也涌现出许多藏书家勤奋抄书、聚书的动人事迹。

藏书文化的兴盛期则为宋代至清末时期,这一时期我国古代的学术文化发展至高峰并进入总结阶段,为典籍的撰作提供了丰富的思想认识源泉。这一时期,也是浙江藏书文化的鼎盛阶段。

明清藏书必称楼阁

早在吴越国时,浙江地区的印刷事业就已十分发达,20世纪初以来,宁波、杭州等地陆续出现吴越时期刻印的佛经经卷,其中雷峰塔经卷更是轰动一时。北宋时,杭刻名冠全国,国子监的很多书都在杭州刻版,宋代藏书家叶梦得评价:“天下印书以杭州为上。”杭州也与北京、南京、苏州并列为国内书籍四大聚集地。

宋以后雕版印刷的普及带来了图书生产上的革命,印刷术使图书的复本量大大增加,图书的流通范围也相应扩大。宋元明清几代,私家藏书这种文化现象冲出士大夫阶层,波及乡绅、豪门、商贾乃至一般的读书人家,藏书家人数剧增。到鼎盛的清代,有明确史实记载的、藏书达5000卷以上的藏书家已超过3000人,并涌现出“清代四大藏书家”。

“四大藏书家”首推“南瞿北杨”,南瞿指常熟瞿镛,生活于清嘉庆、咸丰年间,常熟瞿氏铁琴铜剑楼,藏书丰富;“北杨”指山东聊城杨绍和的“海源阁”,杨绍和生活于清道光至光绪年间,曾任礼部郎中、翰林院侍讲。

“四大藏书家”剩余两人陆心源和丁丙皆为浙江人,陆是浙江归安(今浙江湖州)人,生活于清道光至光绪年间,历任道员、盐运使,喜好收藏宋元珍本,还搜罗许多江浙故家的藏书,使藏书总数达15万卷以上。他的藏书楼“皕宋楼”,号称收藏宋版200部;还有丁丙,浙江杭州人,生活于清道光至光绪年间。他和兄长丁申一起藏书,时称“二丁”。丁家有家传“八千卷楼”藏书。

丁氏兄弟继承先辈事业,且对公家藏书也非常关心。杭州文澜阁《四库全书》因太平军作战而流散,丁氏兄弟发现后便四处寻检收集,后又雇人抄补残缺,历经十几年,基本上恢复了文澜阁《四库全书》的旧貌,至今保存在浙江图书馆。

那个时期,浙江藏书雅阁比比皆是。自晋至清,浙江仅私人藏书家就有400余人,有名可稽的藏书楼达200多处。

在这些藏书楼中,珍藏了数以万计堪称稀世珍宝的古籍善本。藏书楼研究专家顾志兴认为,这些藏书,对知识的保存,对文化的传承,对后代的教育,發挥了巨大作用。

杭州文澜阁,是乾隆皇帝为珍藏《四库全书》而建,是“南三阁”中唯一存留至今的藏书楼。作为镇阁之宝,《四库全书》的内容宏富,几乎汇集了中国古代两千多年历史进程中所产生的主要典籍,收书近8万卷。

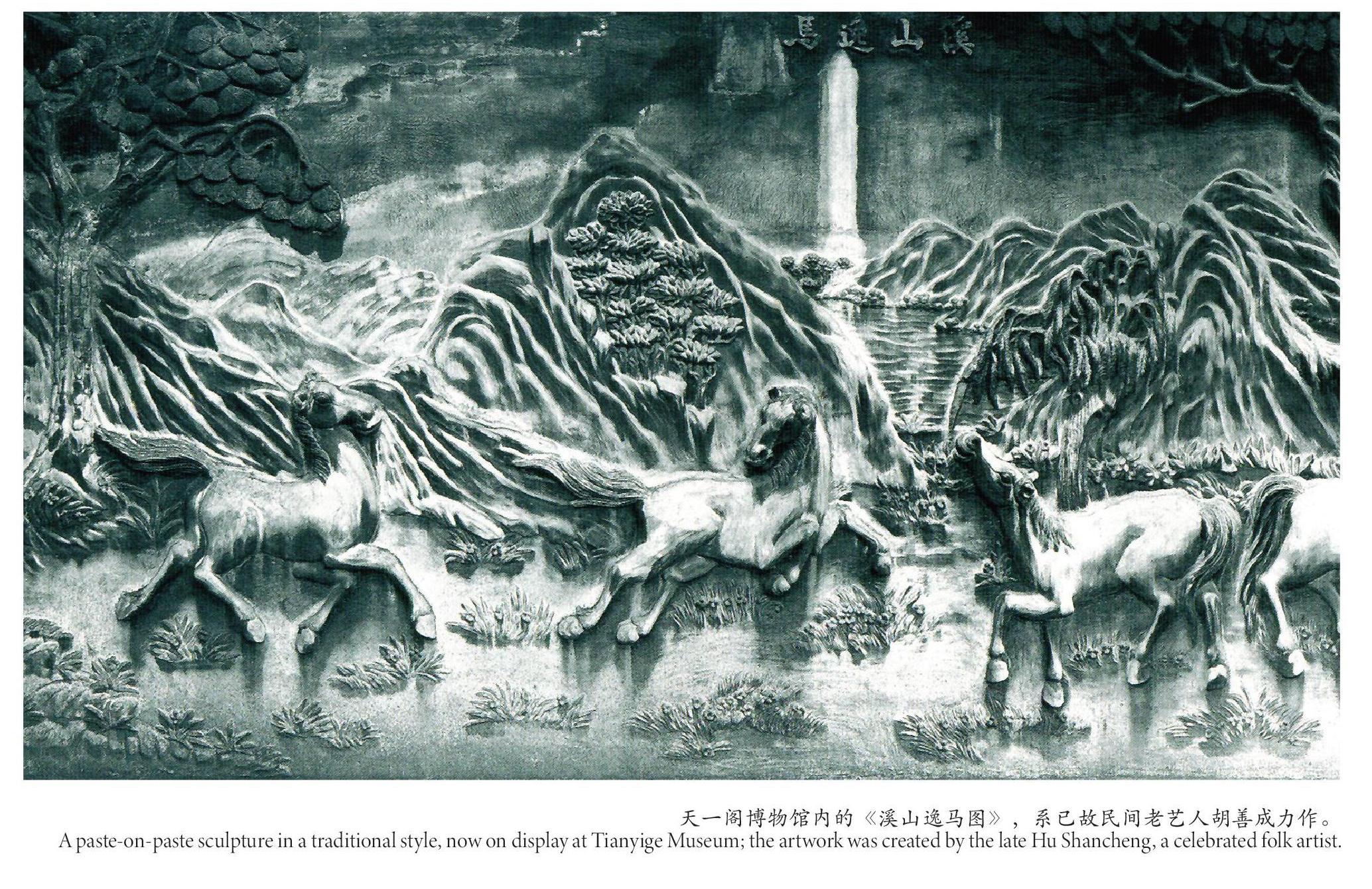

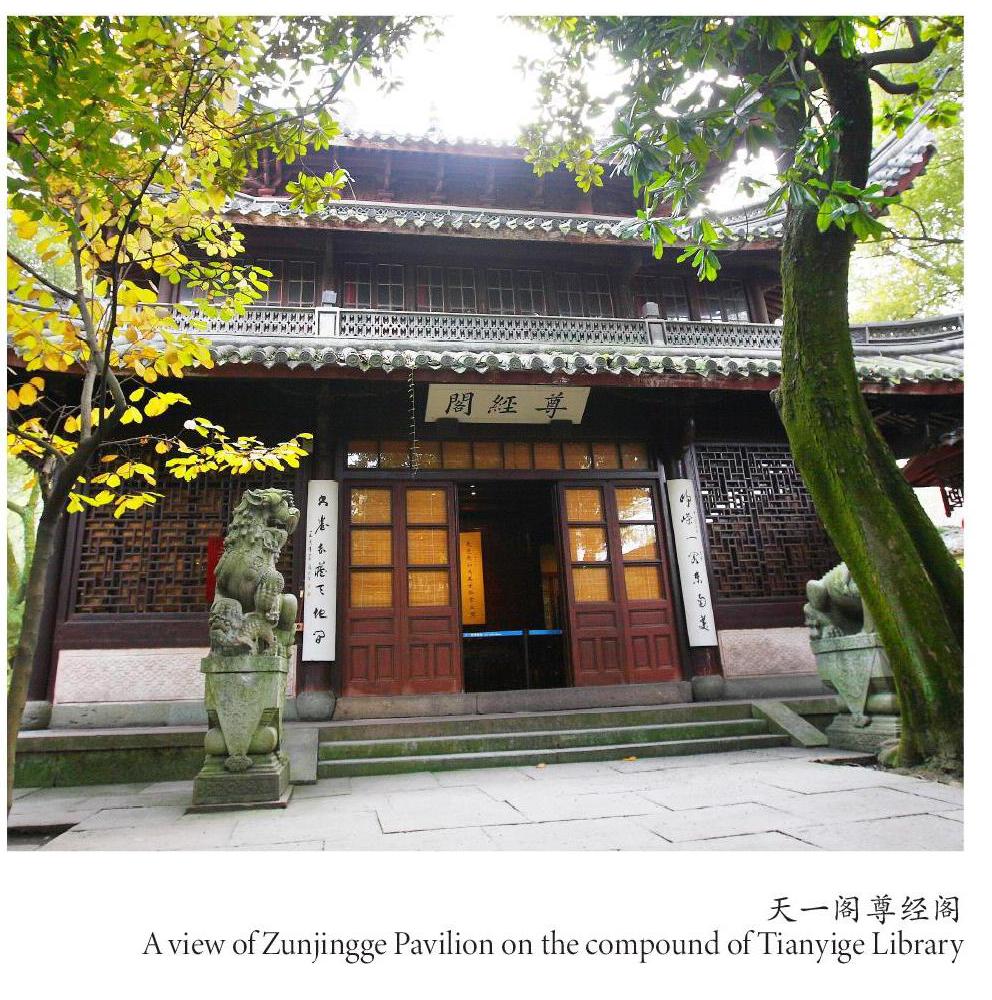

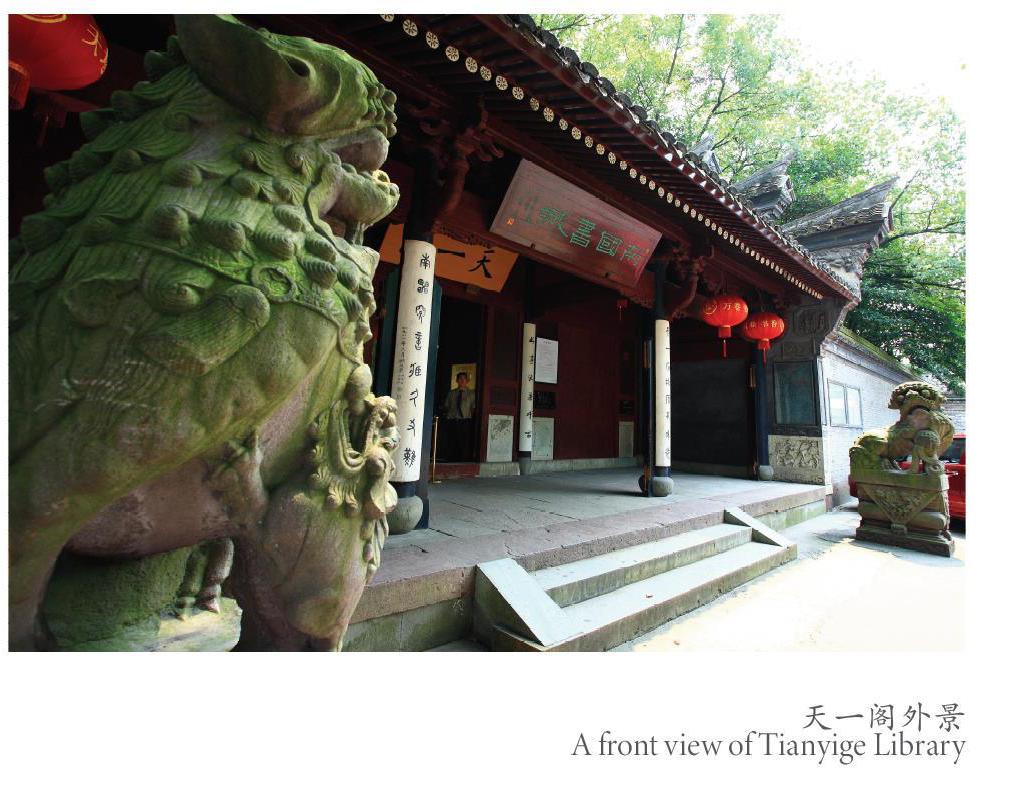

宁波天一阁作为中国现存最早的藏书楼,藏书品种和数量蔚为大观,收藏了271种明代地方志书和370种明代的科举录,此外还汇集了政治、经济、军事、文化、法律等多方面的典章制度及政书。

而湖州嘉业堂,则以拥有众多宋元刻本、明清刊本、稿抄本及地方志书为特色。

此外,清光绪年间孙衣言创建的瑞安玉海楼,为学者的藏书楼,以富有名家批校本、乡邦文献和珍善本闻名于世。

其他私家藏书楼,所藏典籍各有特色。

浙江的藏书楼以名家多、规模大著称。南朝的沈约(德清人),五代的钱惟演,南宋的陆宰、陆游父子和叶梦得(湖州人)、陈振孙等,明代的范氏天一阁、祁氏澹生堂等,至清代有黄宗羲的续钞堂、朱彝尊的曝书亭、汪启淑的开万堂、鲍廷博的知不足斋、卢文弨的抱经堂、吴骞的拜经楼、陈鱣的向山阁、黄氏五桂楼等等数以百计的私家藏书楼。尽管藏书有聚有散,但有些藏书楼都能被完好地保存至今,这在全国各省中是首屈一指的。

但如今,明清藏书楼能完好保存下来的不多,仅有天一阁、玉海楼、嘉业堂等近10座,其他大部分是翻建,或为遗址。

藏书楼大量消失的原因,一是政治与战乱的摧残。南宋楼钥(鄞县人)的东楼,历几十年之聚集,藏书逾万卷。到了南宋末年,东楼藏书终随改朝换代而全数败落。二是后人疏于管理,出售藏书而转向工商投资等。如清代道光咸丰年间南浔蒋维培、蒋维基兄弟创立的俪籝馆。蒋氏后人事业受挫,藏书先后散出,这座绵延百年的藏书楼也未能善其终。三是西风东渐,近代图书馆事业的兴起,取代并极大扩展了藏书楼的社会功能,只有少数藏书楼延续至今。

开放藏书 经世致用

浙江历代的藏书家,大多是学者或知识分子。正是由于对书籍的尊崇和藏书的重要,深感藏而能守则更不易。为了永久保存,很多藏书家订立了严格的管理制度,不肯轻易示人。

然而一些开明的藏书家对藏书的目的较为明确,就是为了经世致用,利用藏书,博古通今,教育学生,著书立说,他们能做到供人借抄、与人共读,甚而博通群籍,终成一代学者。

东汉王充《论衡》一书的传抄和收藏,是浙江私家藏书对外开放的开端。至明末清初,随着浙东史学流派的创立和发展,私家藏书楼纷纷从封闭转向开放,从局部开放转向全面开放。从未让人入阁读书和抄录的天一阁,陆续向黄宗羲、万斯同、全祖望等人开放。当时几乎没有私家藏书楼不向浙东学派学者开放,浙东史学流派代表人物藏书楼也几乎没有不向志同道合者开放。这从根本上突破了私家藏书楼只为自用、少为他用、不为社会所用的致命局限。

两宋时期,浙江已经成为全国经济社会的新兴发展地区,明清时期,浙江更是全国商品经济的领先发展地区。因此,浙江及其杭州不仅是全国刻印出书的重点地区,而且是书院教育的重点地区。

明代浙江著名私家藏书楼几乎无不自行校刻文献典籍和地方文献,并且从以藏书楼之间分刻交换和刊行入市为主,转变为藏书楼和印书业结合为主。有的藏书楼为印书坊提供融资共享利润,更多的藏书楼自立印书坊,收藏和出书合二为一。

晚清海盐张元济创办上海商务印书馆,发展了收藏、出书、借阅合三为一的模式。既以商务编辑所编印出书,又以商务涵芬楼收藏善本典籍。他不仅把家族世代涉园藏书大部分转让商务涵芬楼,一部分捐赠他同朋友创办的上海民办公共图书馆合众图书馆,而且后来还把涵芬楼改名为东方图书馆对外开放,成为民办公共图书馆。

现存清末瑞安孙衣言和孙诒让父子的玉海楼,曾藏书8万卷以上,主要收藏历代文献典籍和瓯越地方文献以及孙氏父子著述,其中不乏孤本、善本,特别是名家批校本以及孙氏父子手批校本。

孙氏父子在建成玉海楼以后,在加强管理的同时,随即向外人公开开放。孙诒让从自己做起,先后创办了专修数学的书院、专修外文的方言馆、专修化学的学堂等,把教育和藏书两大事业推向社会。他还集股兴办矿务、交通、农业、渔业等地方商品化市场化实业,走向社会并且全面地服务社会。这就把浙江私家藏书楼的经世致用文化推向了社会化发展的更新更高台阶。

向图书馆体系演化

在传统藏书楼向近现代图书馆逐渐演化的历史进程中,浙江的图书馆事业建设依然走在前列,肇始于杭州藏书楼的浙江图书馆是我国最早的公共图书馆,徐树兰建成的古越藏书楼则是我国最早的私人图书馆。

民国时期历次全国图书馆调查统计,浙江的图书馆数均居前列。在历史上,浙江近代的图书事业也是盛名已久。1932年,浙江省立图书馆大学路总馆落成开放。1936年4月19日,浙江省图书馆协会宣告成立。浙江图书馆强调其社会服务功能,编有刊物《浙江省立图书馆馆刊》《图书展望》《文澜学报》等多种,定期组织学术演讲。

新中国成立以来,浙江在调整、充实原有图书馆的基础上着手发展各种类型的图书馆。全省各类图书馆都已建立,数量、规模也颇为可观。十一届三中全会以来,浙江的图书馆事业建设在全面恢复后迅速发展:图书馆数、藏书总量急剧上升,藏书结构有所改善,藏书质量普遍提高,馆舍、设备也有了较大改善。

2016年,浙江省政府出台《公共图书服务规范》,首次明确指标:县级馆藏书须达人均1册,省级中心镇或常住人口超过10万的乡镇(街道)设立公共图书馆分馆。2018年,浙江省政府发布重磅文件全力打造浙江文化金名片,要求整理出版浙江优秀传统文化类重要典籍,建设古籍资源库、浙学文献中心总库。

至2020年,浙江共有公共图书馆103家、文化馆101家、博物馆366家、非遗中心101家、乡镇(街道)综合文化站1365家、农村文化礼堂14341家,每万人享有图书馆、文化馆站、博物馆面积1371.4平方米;图书馆藏书总量达9432.94万册;人均纸质图书拥有量1.61册。

在这其中,杭州图书馆已然成了杭州的新地标,更因为它的开放、包容获得了社会各界的好评,被网友赞为“最温暖的图书馆”。处在之江文化中心的图书馆新馆无论是藏书量还是建造面积都排在全省各大图书馆的第一位,这座满怀全浙江人民期待的地标性文化中心将成为未来浙江的又一张人文名片。

值得一提的是,在数字化浪潮下,公共图书馆的传统疆域正不断被“攻城略地”。在此背景下,傳统图书馆纷纷转战云服务和移动互联网终端领域,推开“数字化大门”。诸多公立图书馆也开始从单一图书借阅向多元化文化服务转变,从“书”的空间变成“人”的空间。

当下,图书馆可以是精致的书房,也可以是“书友会所”或“动感驿站”,它正以温馨的空间环境、多元的服务内容、丰富的文献资源、多样的文化活动,成为城市的“公共文化客厅”,从“藏书楼”变身“城市客厅”……藏书文化在一次次变局中实现升华,成为现代社会中一座座“文化灯塔”,让书香飘散人间。

(本栏目图片由浙江省博物馆、宁波市委宣传部、瑞安市委宣传部和湖州市南浔区委宣传部提供)

Libraries in Ancient Zhejiang

Book collection in China can be traced back to the Spring and Autumn (770-476BC) period in Chinese history. Back then, books were bamboo or wood slips joined together to form whole scrolls. The Qin Dynasty (221-207BC), a unified empire, set up a special library where books seized from all the states through the war were stored.

After the Han Dynasty (206BC-220AD) succeeded the Qin, an official library system was set up. The empire had three national libraries that housed books from the central and regional government collections of the previous Qin. A government department was set up to administer all the affairs about the libraries and archive government documents for future reference. The department was also in charge of making records as it was manned by historians.

In the early years of the Han Dynasty, books were rare. The central government called for book donations. From 124AD on, books flooded in. A large quantity of bamboo slip books, which had been hidden from the government due to the book-burning policy at the decree of the First Emperor of the Qin, was unearthed and donated.

In the Jin Dynasty (266-420), private book collections emerged. In the Sui (581-617) and the Tang (618-907), over 20 private book collections amounted to more than 10,000 books each. During these centuries, academic and cultural undertakings thrived in China. Confucian classics, history, philosophy and literature as well as Buddhist and Taoist sutras greatly outnumbered their counterparts in the Han Dynasty.

Zhejiang in eastern China was a book publishing powerhouse during the Wuyue Kingdom (907-978) period, as testified by Buddhist sutras unearthed in the 20th century in Ningbo and Hangzhou. In the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), Hangzhou was a national book publishing center. Even the Imperial Academy in the capital used books printed in Hangzhou.

Private libraries thrived in Zhejiang in the dynasties of the Song, the Yuan (1279-1368), the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing (1644-1911) thanks to the advancement of block printing technology and thanks to widespread education at grassroots level. History records that the Qing Dynasty had over 3,000 private libraries whose collections amounted to more than 5,000 books. Qu Yong, Yang Shaohe, Lu Xinyuan and Ding Bing were four major book collectors of the Qing Dynasty. Lu and Ding were natives of Zhejiang. Lu Xinyuan (1838-1894) was from Huzhou in northern Zhejiang. His career as a government official lasted decades. His private collection boasted 200 books printed in the Song and he proudly called his private library “200 Song Books”. The books in his collection numbered 150,000. Ding Bing and his older brother Ding Shen owned a private library of 8,000 books. But the two brothers most outstanding feat was that they salvaged the books from the Imperial Library housed at Wenlange Library in Hangzhou. The imperial library was looted and ravaged by the rebels when the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom seized Hangzhou. Thanks to the Ding brothers, the books from the imperial library were salvaged. Later, the brothers hired scribes to make copies missing from the library. The copying project went on for more than ten years and later it was carried on by other people.

The majority of private libraries in Zhejiang vanished in history largely due to political turmoil and war. Take Donglou Library in Yinzhou during the Southern Song Dynasty for example. It vanished after the dynasty was down and out. Some private libraries didnt survive history largely because family fortunes ran out and books were sold for cash. In modern times, the number of private libraries dwindled principally because public libraries came along and served the public.

For a long time in history, most private libraries in Zhejiang did not open to readers. These libraries were considered private assets. Yet, some collectors were willing. The first book that was copied from a private library in Zhejiang was Lun Heng by Wang Chong (27-c.97AD), a scholar of the Eastern Han Dynasty. It was during the last decades of the Ming and the early decades of the Qing that private libraries in the province began to embrace readers. Tianyige Library in Ningbo chose to allow some prominent scholars to read books and make copies at the library. On the list of the guests were Huang Zongxi, Wan Sitong, and Quan Zuwang, all great scholars of the time. In fact, all private libraries in the province opened their doors to scholars of the East Zhejiang School.

And private libraries in Zhejiang did more than open their doors to scholars. In the Ming Dynasty, almost all private libraries in the province turned out their own editions of old books after a process of edition and annotation. They also reprinted some regional annals. Some libraries worked together with printers and some published books on their own.

Zhang Yuanji (1867-1959), a native of Haiyan in northern Zhejiang, set up Commercial Press, one of the most prestigious book publishers in China. With Zhang, Commercial Press not only published books, but also operated Henfenlou Library. Zhang donated a large part of his private book collection to the library. The rest of the collection went to a public library in Shanghai. The library of Commercial Press was later turned into a public library.

In the 20th century, Zhejiang led China in building up public libraries. In 1932, Zhejiang Library opened to readers. It is Chinas first public library. In April 1936, Zhejiang Association of Libraries came into being.

Data at the end of 2020 indicates that Zhejiang had 103 public libraries, 101 cultural centers at municipal and provincial level, 366 museums, 101 centers of intangible cultural heritage, 1,365 cultural centers at town and urban neighborhood level, 14,341 village cultural centers; the total number of the books at the libraries and other cultural institutions across the province amounted to about 94 million.