Internationalisation and the Development of Vietnamese Theatre

Dinh Thi Nguyen, Director of the Hanoi Academy of Theatre and Cinema, introduces his theory of Internationalisation in Vietnamese theatre. He suggests that traditional performance forms are always being intermingled with foreign performance forms, with intercultural mixing of forms creating “internationalisation”. In this paper the development of Vietnamese theatre forms are examined through the lens of internationalisation. Starting with Cheo and Tuong, this paper follows the ways in which adaptations and absorption of introduced forms of theatre have shaped traditional forms developing into the contemporary theatre practices seen today in modern Vietnam.

Keywords: traditional Vietnamese performance, intercultural theatre, contemporary Vietnamese theatre

Introduction

In the last decades of the 20th Century and the first of the 21st Century, the growing number of international performance festivals and cultural exchange projects have been breaking down barriers between the world’s theatre cultures. An international community is emerging where both those who make and consume theatre have become increasingly familiar with a diversity of forms and issues presented on stages of all nations. However, there have evolved a series of new theoretical “isms” in the theatre today that need to be strongly questioned. This phenomenon is opening up new relationships between theatre cultures that are eroding the specificities of their own traditions.

A prominent area for international exchange, theatre culture will be susceptible to cross-cultural influences. Recent theatre practices reveal that theatre practitioners adapt, assimilate, borrow or innovate in response to a wide range of contacts and encounters, forced or voluntary. Old forms are constantly being remoulded to the requirements of today. New practices are being created and, if accepted and practised for a time, become absorbed into traditional practice.

In this paper I map out a conceptual framework for analysing a number of related practices in adapting and borrowing elements or techniques from one theatre culture to apply to another. I then proceed to investigate the developmet of Vietnamese performance genres in relation to the theory I establish—that of Internationalisation. I perceive this process of internationalisation like a quarry used to create one’s own works from raw materials gathered from a vast treasure house of cultural tradition. Those works should be considered as experimentation to achieve a true integration of the “Other” and your “Own”. In a metaphoric way they may be seen as the myriad colours of rainbow within which the primary colours are still recognisable.

The question is whether this process, as complex as the many variants of cross cultural exchange in the theatre, can be encapsulated by the term “internationalisation”. Is it a collaborative process in which foreign elements equally exist with the original tradition and then create a new form which becomes familiar? Or are they assimilated into the tradition and absorbed by it? Do “foreign” elements remain foreign, used within familiar structures—thus demonstrating their Otherness?

Those questions have compelled my practice. Like other theatre cultures—particularly Asian ones—Vietnamese theatre practitioners face an issue of how to preserve our cultural identity while engaging fully with the international community.

The impacts of colonialism in Vietnam are both conceptual—the introduction of foreign models—and practical—the introduction of invasive political and economic structures. The imposition of foreign theatrical models makes cultural identity problematic both in thought and in action. A difficult question, for Vietnamese scholars and theatre practitioners, is the extent to which this objectification indexes theatre culture change—the adoption of foreign modes of self-perception. There has been a public debate in Vietnam about whether consciousness of Vietnamese traditional theatre is indigenous or whether this awareness reflects introduced theatrical categories which may be used in response to situational contingencies or to bring contemporary practice into line with what is believed to be a new presentation of tradition.

My assertion that tradition is the contemporary interpretation of the past, rather than something passively received, is a crucial element in a theory of preserving tradition. My point is that in theatre cultural identity must be understood as creative and dynamic, and such an understanding is only possible with a symbolic concept of culture.

In utilising the concept of “internationalisation” of theatre, I am less interested in creating a new genre than, through analysing and comparing different models, in searching for a stimulus to strengthen my own theatre culture. This is essential not only for my own works but also for the young Vietnamese generation who are struggling for a new theatrical identity in which they can demonstrate their creativity. After many years working with young directors and actors, I have seen their hunger for changes to old fashioned theatre forms which no longer attract contemporary audiences.

This paper begins this process by analysing the past

Vietnamese Theatre Cultureand an Approach to the Context of Internationalisation

Vietnamese theatre was established and developed in conjunction with religion, just as European theatre practices were through early Christrainty and classical Greek theatre through religious ceremonies. However in Vietnamese theatre, theatrical elements could not be separated or recognised independently. While in Europe, five centuries before Christ, Greek theatre could offer humankind works by great authors like Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes and a theatrical theory by Aristotle, Vietnamese theatre’s birth was based on religious rituals and folklore elements which cannot be distinguished as theatre performances. Moreover, though established in the 13th century it was influenced by foreign colonisers for many centuries (Quang, 1998, p. 8).

In the development of Vietnamese theatre, the enrichment of the theatrical form through the absorption of foreign elements was not always in accordance with the notion of internationalisation. Often the introduced Historical Background

Vietnamese theatre history could be read as a narrative of learning and adapting while, at the same time, trying to resist domination by foreign cultures.From its birth, there were influences from foreign theatre cultures, particularly the Chinese1 and the French2. Though in the struggle for national independence Vietnamese artists were trying to preserve their own cultural identity, it is impossible to deny that the development of theatre culture parallels with the growth of cultural exchange between nations. Were those exchanges a passive reception of an invading colonial culture or were they a conscious choice?

Cheo and Tuong: Borrowing and Adapting Chinese Opera/Sung Drama

Under the Ly-Tran dynasties (12th-13th Centuries), the arts of singing, dancing and performance had become very popular in Vietnamese society. However a theatre art form, in a general context, had yet to be established. Performances of dance and song were merely an imitation of life’s everyday activities reflecting Vietnamese people’s aspiration for a better life. But they formed the foundation for creating a rapidly expanding theatre culture. During this period, a Mongolian war prisoner, Ly Nguyen Cat, was teaching dance and singing for people of the Royal Art group,3 which became a driving force in the foundation of Vietnamese traditional theatre.

Under the Le dynasty (15th Century), Vietnamese theatre was invigorated through a combination of the following elements:

(1) The art of singing, dancing, music, and verbal spectacle expanded in a wide range of forms.

(2) The creation of written literature and Vietnamese language.4

(3) The influences of Chinese theatre, especially Chinese opera.

However, in terms of genre, there was no discernible form which can be identified by historians. In the late 15th Century two tendencies evolved in the presentation of performances. One used folk tales, dance and music; this developed to become Cheo. The other was focussed upon stories related to the Royal government which became Tuong. Both Cheo and Tuong represent a still flourishing classical Vietnamese performance tradition.

The period from the 16th-18th Centuries has been described “as an artistic mutation” (Ngu, 1996, p. 277) in which performing art improved to a higher level by expanding short spectacles to become full-scale performances. With the creation of their own language, performers could use Vietnamese scripts to produce theatre performances instead of using Chinese stories. This brought great opportunities for performers to add more and more elements of Vietnamese folklore to their performances of dance, song and music, thus identifying a Vietnamese culture. Moreover, the exchange between indigenous religious ritual and other religions5 enhanced Vietnamese traditional theatre’s ability to reflect its society (see Figure 1 and 2).

The increasing development of Vietnamese literature and poetry had a strong impact on performing arts.6 As a result, “in the 18th and early 19th centuries Cheo [and Tuong] became an epic theatre” (Bang, 1999, p. 47) with the creation of a number of Vietnamese plays in these genres, indicating characteristics of a burgeoning and unique theatrical form.7

Of course, the growth of traditional theatre with a strong Vietnamese identity offended Chinese feudalistic dominators who had always been ambitious to assimilate Vietnamese culture.8 Furthermore, through theatre performances Vietnamese intellectuals criticised their Royal government authorities who had become corrupt and heavily controlled by Chinese feudalism.9 It can be said that Vietnamese theatre culture had historically been eager to learn and absorb from other theatre cultures, but continuously resisted cultural assimilation.

The Establishment of Spoken Drama within the Influence of French Theatre

Before discussing the influence of colonial French theatre on traditional Vietnamese theatre it is necessary to understand that Cheo and Tuong traditions were primarily movement and musically based theatrical forms. French theatre in Vietnam became known as Spoken Drama. Any Vietnamese theatre using primarily spoken dialogue became known as Spoken Drama.

There are two opinions regarding the establishment of Vietnamese Spoken Drama:

(1) The first point of view holds that Spoken Drama’s birth was inherent in Vietnamese traditional theatre, such as Tuong and Cheo, since in those theatre forms there are elements of “speaking”.10

(2) The second point of view states that Vietnamese Spoken Drama was imported from the West, particularly from France.

The establishment of Vietnamese Spoken Drama met the aesthetic demands of urban intellectuals and audiences for a theatre form that was closer to their lives in the 1920s. At the time, existing traditional theatre forms no longer attracted this audience; Tuong was performed with stories about Royal government, and Cheo reflected moral issues relating to country people. In step with day-to-day changes within society, Vietnamese theatre practitioners had been trying to renovate their performances, but they perceived they could not save themselves from gradually falling into oblivion. “During the 1920s, under the French colonisation, rural areas were pauperised and Tuong and Cheo had lost their audiences. Performers had to move to big cities where the Europeanisation was rapidly expanded” (Bang, 1998, p. 209). They sought a more suitable theatre form that facilitated a direct approach to social issues; they found Western drama—particularly French classical drama—more flexible in reflecting the human condition, since performers did not have to include song and dance. In Spoken Drama, actors mostly use physical and verbal actions, movements close to everyday life—although those elements are consciously selected, a refinement of naturalism.

It can therefore be said that the evidence points toward Vietnamese Spoken Drama being established within the influence of French classicism in the 1920s. In his book “An Application of Stanislavsky’s Method to Actor Training” (Su, 2005), Hoang Su agreed that “it is hard to share with theatricals who have the opinion which state:Vietnamese spoken drama was rooted from traditional theatre because the strongest foundation of drama is literature from which a written script is created and dramatic actions are developed whereas speech in traditional theatre has to respect its conventional melodies” (Su, 2005, p. 15). It is a tenuous observation to consider Vietnamese traditional theatre resulting in Spoken Drama because these two forms use very different techniques.

Late 19th Century—Early 20th Century: Absorbing French Theatre

Following the introduction of Spoken Drama into Vietnam in late 19th Century there have been many theatrical experiments in cultural exchange, some of them before terms such as “interculturalism” or“transculturalism” were fashionable. At the same time, Vietnamese theatre practitioners were attempting to modernise traditional theatre. By combining Western techniques with Cheo and Tuong, they wanted to give Spoken Drama a national character. In other words, they wanted to enrich their own theatre culture in parallel with protecting their cultural identity when making theatre. Certainly, this process was not smooth.

The impetus to discover what value Spoken Drama had in Vietnamese society has been a matter of heated debate since the 1930s. What elements from French theatre we could apply to traditional theatre without distorting traditional characteristics? Whether theatrical practices adapting French techniques could be used in the struggle for independence against French colonial domination have long been questioned.

In the early 20th Century, after the French had established their colonisation of Vietnam, there were a large number of Vietnamese intellectuals trained by a French-focused education system. In many French-Vietnamese schools, plays written by Corneille, Racine and Moliere were introduced to Vietnamese students who were required not only to study them but also to create performances based on those texts. In high schools, Vietnamese students learned French theatre by analysing its structural aspects together with the creation of character, style and genre in plays written by not only classical but also contemporary French playwrights.

The development of a national play writing style required an official and professional system of performances which had not yet formed by the 1930’s. A viable performing arts culture is not simply the capacity to transform a written script into a production on stage. Its ability to stimulate scripts and, more importantly, to create a cultural identity through its production styles and characteristics is paramount. So, the development of a theatre culture demands a parallel growth of performance and play writing styles. Unfortunately, at that time Vietnamese theatre practitioners had no opportunities to learn acting and directing for Spoken Drama, apart from watching a few French performances undertaken by visiting French theatre companies.

Some theatre practitioners appropriated Cheo and Tuong masters to create what are described as Cheo van minh (“civilised” Cheo) and Kich Cheo (a mixture of Cheo and Drama). In these forms, scenery and the decorated stage used the conventions of Western realistic theatre to specify the action’s location. They removed all characteristics of traditional Cheo such as conventionalised scenes, stylised movements, and songs. As a result, they generated a discernible form. It is difficult to define such performances: are they Cheo or Spoken Drama?

In Hanoi and Saigon, French opera houses, very different from Cheo and Tuong performance spaces, were built in 1911 for French theatre companies performing for French audiences—including authorities, soldiers, business men and women. Later a number of Vietnamese involved in relationships with these French had opportunities to watch these performances. The change of performance spaces generated a new way of receiving theatre works: the audiences came to theatres for watching performances only, not for talking about their everyday lives. It is important to note that in Vietnam until 18th Century performances had been presented at pagodas, temples ormarkets where ordinary people came for social meetings rather than for enjoying performances (see Figure 3). The introduction of proscenium theatre of Western style was carried out in 1911 when the French performed their theatre works in Hanoi and then in Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City). These events resulted in the foundation of a number of drama groups.

The first Spoken Drama performed by Vietnamese actors in Vietnamese occurred on the 25th April 1920; it was Moliere’s play “Malade Imaginaire”11 since there had not yet been a written play in Vietnamese. This script may also had been chosen because Moliere’s comedies are close to Vietnamese Cheo in the way they reflect society satirically. The performance of “Malade Imaginaire” encouraged Vietnamese writers to create their own stories reflecting Vietnamese society. Following this event, many original Vietnamese plays12 were shown at several small performance spaces.13 However those performances were considered as preparatory for the official establishment of Vietnamese Spoken Drama.

On the 22nd October 1921 the premiere of the play “Chen thuoc doc” (A Cup of Poison), written by a Vietnamese playwright Vu Dinh Long, was performed by Vietnamese artists at the Hanoi Opera House. It is seen as the foundation of Vietnamese Spoken Drama.14

The introduction of French theatre was not only a step toward the creation of Spoken Drama but also a strong influence on Vietnamese traditional theatre particularly Cheo and Tuong. Professor Tran Bang contends this “is a complicated confrontation which causes both negative andpositive results” (Bang, 1998, p. 209)

A substantial negative result of French colonisation was that it brought great economic poverty to Vietnamese people living in the countryside; traditional theatre, very popular in rural communities, could no longer find its audiences. Cheo performers had to bring their performances to the big cities and, in order to attract urban spectators. Cheo masters had to make their performance relevant to audiences who had seen French theatre.

Unlike the three unities rule of French classical drama,15 a Cheo play is a sequence of actions and events which sometimes tell the whole life of a character and within which all actions take place in unlimited spaces. Originally Cheo was performed in the entrance square of Buddhist temples and pagodas or in markets where there was no distance between performers and spectators. These open spaces enabled performers to gain better communication with their audience. People came to performances not only to see the show but also to talk and meet friends and relatives, a social communication. Once moved to cities, performers had to modify their Cheo productions so that they could perform in an opera house/proscenium theatre, known as “theatre of boxes” (san khau hop) in Vietnam.16 This type of performance space not only greatly modified the performance but also enforced a new kind of audience response. Traditional scripts were rewritten in a realistic style to better encompass contemporary stories.

In summary, Cheo theatre had to break its traditional principles to survive. Viewed sympathetically, it is understandable that traditional artists of the time had no choice but to abandon peasant farmers—their traditional mainstream audience—in order to engage with the “petty bourgeoisie”.

The Establishment of Cai Luong

Meanwhile in the South of Vietnam in the early 20th Century, under the influence of the French drama and Tuong, a new form of popular theatre arose. Cai luong was created by combining folk music with realistic-style acting.

Like Cheo in the North and Tuong in central Vietnam, Cai luong had a strong foundation in Southern folk songs and music. During the late 19th Century Southern folk songs and music had been rapidly developed throughout Southern provinces. “Many families formed their own amateurish groups to perform for their communities” (Yen, Su, & Ngu, 2000, p. 65). Through absorbing French drama, some Cai luong masters17 created performances using Vietnamese poetic stories.18 These Cai luong masters’ groups were financially supported by a French educated intellectual, André Than. One of the most famous groups was SaDecamis and“its first performance of ‘Luc Van Tien’ in 1917 in Vinh Long town was a foundation of Cai luong” (Yen, Su, & Ngu, 2000, p. 68). It can therefore be said that from its birth, Cai luong was influenced decisively by two theatrical currents: Tuong and French drama.

Moreover, through contact and exchange with Chinese sung drama from Guang dong province in China19 as well as with Western music, Cai luong selectively absorbed new elements by adding new musical instruments into its original orchestra, such as guitar, mandolin and violin.

By absorbing Tuong’s stylisation and French realistic acting style, “Cai luong managed to create an‘intersection’ of these contradictory structures. […] This blend enabled Cai luong theatre to cope with the inevitable modernisation generated by the time, while preserving its national essence and its dramatic peculiarities” (Hanh, 1998, p. 32)

Clearly the presence of French theatre in the early 20th Century generated a vast change to Vietnamese theatre, the evident impact of one theatre culture on another and further evidence of Vietnamese theatre’s development through imposed international “exchange”.

However it is necessary to point out that the genre which Vietnamese theatre adapted most over this period of time was primarily classical theatre. Not all variations or trends in French theatre had equal influence; Vietnamese society at this time was only introduced to French classical drama. More contemporary forms of French theatre were not shown in Vietnam. At the time when Vietnamese theatricals started their drama, French theatre had departed from classicism by raiding other cultures for inspiration; witness the “Turkish” scenes in Moliere, Voltaire’s use of Chinese elements, and more recently, the continuing interest in Oriental theatre by major French theatrical innovators, from Antoine to Artaud, J. L. Barrault and Ariane Mnouchkine.

Simultaneously the influence of Western theatrical techniques, especially modern realism has been enormous even in those Oriental countries with rich theatrical traditions of their own such as India, Japan and China.20 While Vietnamese practitioners saw Western drama as a flexible means of representing human life, easily absorbing techniques like realism, Western theatre practitioners like J. L. Barrault and M. Marceau, who visited Vietnam in 1960 and were inspired by Vietnamese classical forms of Cheo and Tuong, called them models of “total theatre” (Quang, 1995. p. 272). Still earlier Artaud had a similar response to Indonesian Balinese theatre and called it a model of “pure theatre”.

It is apparent from the Vietnamese experience that increasing international connections have intensified interest in international theatre exchanges.Among the most important exchanges for Vietnamese theatricals was Stanislavsky’s psychological realism.

From 1954-1975: The Influence of Stanislavsky’s Method.

During the anti-French war (1946-1954) selected Vietnamese young people were nominated to join workshops on Spoken Drama where they studied Stanislavsky’s method through translations from Chinese.21 After the victory, theatre and film schools were opened in North Vietnam to train professional directors and actors for Spoken Drama and film, while a large number of Vietnamese dramatists were sent to study in the former Soviet Union. Returning home, those Soviet-Russian trained people became a new generation of directors and theatrical scholars whose exploration and studies of Stanislavsky’s method became broadly transformed throughout Vietnamese theatre culture. “A study of Stanislavsky’s methodology to apply it to our spoken drama and film was undertaken in various ways” (Su, 2005, p. 17). It is again implied that, under the influence of a“foreign” theatre form, Vietnamese theatre changed rapidly after applying Stanislavsky’s acting method to both Spoken Drama and traditional theatre: Tuong and Cheo.22

During the 1960s and 70s a large number of realistic style drama productions were warmly received, particularly since they well served the government in reflecting reality within Vietnam: Stanislavsky’s method was seen as an officially sanctioned guide for making theatre. There were two primary reasons. Firstly, during the war, Vietnamese dramatists had few opportunities to share experiences with artists apart from Soviet-Russians, who were dominant in Vietnam both economically and politically. Secondly, Vietnamese practitioners realised that through making theatre they could serve the government’s cultural policy of reflecting Vietnamese society through realism as well as generating propaganda for the anti-American war.

However it would be improper to deny that many good quality theatre productions using Stanislavsky’s acting and directing style were effective, not only in Spoken Drama but also in Cheo and Tuong.23 By using Stanislavsky’s method, Soviet-Russian trained directors24 “created an artistic and creative environment where Tuong performers better built up their traditional characters” (Yen, 1998, p. 116). The working method of analysing characters’ life by creating and developing a “spine” of psychological/inner and physical/outer dramatic actions was not familiar to traditional performers. However it helped them to explore their characters in a creative way, rather than passively emulating previous generations.

In parallel, many written works were published by theatrical scholars who explored theoretically Stanislavsky’s method.25 These works not only provided Vietnamese theatre practitioners with a useful background, but also were used as text books for training directors and actors in theatre and film schools.

However, through an incomplete understanding of the difference between theatrical forms, in some Tuong and Cheo productions26 Stanislavsky’s method was applied inappropriately. It can be said of them that they were“edging their foot to fit wrong size shoes.”27 Ironically the idea of modernising traditional theatre through a realistic performance style was inverted by turning Cheo and Tuong characters into contemporary ones; for example, they reduced princes and historic personalities to stereotypical figures enthusiastic to fulfil political duties during the 1960s-70s. By rewriting Cheo and Tuong plays using a realistic style without questioning whether realism suits a Cheo play’s structure, the notion of “internationalisation” was used to poor effect. Similarly, musicians in Vietnam attempted to reform music by using motifs from Western opera.28

These hybrid forms without appropriate cultural understanding demanded a solution which was called a“movement of renewing Vietnamese theatre culture”, particularly prevalent at the end of the anti-American war in 1975.

From 1975-1990: The Renewal of Vietnamese Theatre

After unification of the North and the South following the anti-American war,recognising the importance of strengthening their own theatre, dramatists undertook many activities to renew Vietnamese theatre culture in a“new age”. One strategy was to apply techniques taken from other theatre forms whilst preserving a national identity.29

As detailed earlier in this chapter, at this point in time Vietnamese theatre consisted of two categories—traditional theatre and Western-style Spoken Drama. While the former inherited the highly stylised traditions of centuries, the later was largely modelled after Stanislavsky’s method.

Although Stanislavsky’s method had been widely accepted during the 1980s, many Vietnamese dramatists turned to non-realistic Western theatre, while persisting with Vietnamese traditional theatre. There were two reasons.30

Firstly, during the war, both traditional theatre and Spoken Drama had been used for propaganda in which Vietnamese artists were expected to write and produce realistic plays about the political reality of Vietnam. However, after the war Vietnamese artists realised that it was a mistake to apply principles of realism to non-realistic traditional theatre; it resulted in a mono-toned nuance in both theatre styles. Therefore Spoken Drama artists began looking for forms that could express their feelings more vigourously. Similarly traditional theatre practitioners were very interested in modernising Cheo and Tuong before they became antiques being shown in museums.

Secondly, in the wake of the government’s open-door policy,31 works of non-realistic Western theatre artists, such as Brecht, Peter Brook and Grotowski, were introduced into Vietnam.In addition, through international cultural exchange programmes numerous Vietnamese theatricals had opportunities to study and perform in Western countries. In return, Western theatre artists were welcome to collaborate with Vietnamese artists.

It was largely Western theatre artists’ interest in Vietnamese and Asian theatre that inspired many Spoken Drama directors like Nguyen Dinh Quang and Nguyen Dinh Nghito look back at their own theatrical legacies and explore the possibilities of integrating the expressive styles of Cheo and Tuong into Spoken Drama.32 They found that Cheo and Tuong’s fluidity in scenic structure, unlimited stage presentation of time and space, and various stylised staging conventions not only enabled playwrights and directors to realise their broader vision on stage, but offered ample opportunity for actors to move more expressively beyond daily life representation. Those directors also found that one of the best ways to characterise Vietnamese spoken drama in its national identity was to apply Cheo and Tuong principles to it.

Nguyen Dinh Nghi believed that “it [traditional theatre] is the best way leading me to a modern theatre. I am greatly in debt of it” (Nghi, 1978). His production of “Hon Truong Ba Da Hang Thit”33 (Truong Ba’s Spirit in the Butcher’s Skin), a symbolic play about the struggle between good and evil, was an example. The story is about a good man whose spirit, after his death, is transformed to a dead Butcher’s body, who becomes alive again with his own body but the good man’s spirit.34 Symbolically, the play’s message is that a good man’s spirit should be retained to create a better society. In this production, Nguyen Dinh Nghi successfully applied traditional theatre principles by using stylised representations of time and space. He achieved a true integration of traditional techniques and Western style drama (see Figure 4 and 5). “The production [Truong Ba’s Spirit in Butcher’s Skin] was a suggestion of how to make our [Vietnamese] spoken drama become more Vietnamese”(Thai, 2002).

Meanwhile some directors35 were breaking away from the conventions of traditional theatre to produce plays in a more realistic style.36 They blended contemporary subjects and realistic elements37 with old conventions designed to represent ancient themes and peoples. Together with the above mentioned directors, a number of Russian trained ones continued to experiment with applying Stanislavsky’s method to traditional theatre productions.38 Some of them were successful in using Stanislavsky’s “actor preparation” to improve traditional acting skills while maintaining traditional fundamental principles.39

During the 1980s some Vietnamese theatre scholars found Brecht’s dramaturgy to have parallels with Oriental theatre, particularly Vietnamese traditional theatre. In comparison with Brecht’s techniques, Vietnamese Cheo and Tuong make a similar use of alienation to distance their audiences from the living part of characters. Ancient Cheo and Tuong also placed audiences in an objective role by using a directorial ideology which fostered dismissal of critical thinking, whereas Brecht’s techniques enhance the spectator’s ability to critically comprehend a story’s content. It suggests that Brecht’s techniques help to enlarge the role of audiences by giving them more opportunities to develop their imagination and critical faculties. Also it has been recognised that Brecht’s epic theatre has direct application to the question of how contemporary Cheo and Tuong stories might better be represented.40

Consequently some theatre directors consciously applied Brechtian alienation to both Cheo, Tuong and Spoken Drama: Dinh Quang suggests: “Actually, being rooted from an Eastern epic theatre form, we should explore Western experiments of epic theatre, particularly Bertolt Brecht’s theory which is closer to our traditional method of play writing and acting rather than being influenced by Aristotle’s theory which is very different from ours” (Quang, 2004, p. 111). Following that trend, there have been a number of successful experiments applying Brechtian techniques to traditional Vietnamese theatre.

The National Cheo Theatre Company’s production of Caucasian Chalk Circle productively combined Brecht with Cheo;41 utilising Cheo’s traditional stylised movements, gestures and chorus, the director achieved a homogeneity without breaking Cheo principles.

Two wooden rostrum were the primary elements of the stage setting (see Figures 6 and 7). Brecht’s river and the bridge by which Grusha crosses it were indicated exclusively through actor’s movements. Grusha’s journey from one rostra to the other using Cheo’s movements, singing and music demonstrated the dramatic tension of the situation. Her adventures, told in a series of short scenes rather than in continuous time, were depicted by various motifs of Cheo dances and music. For example, the singers in Cheo are separated physically from the physical performers who act and dance on stage.

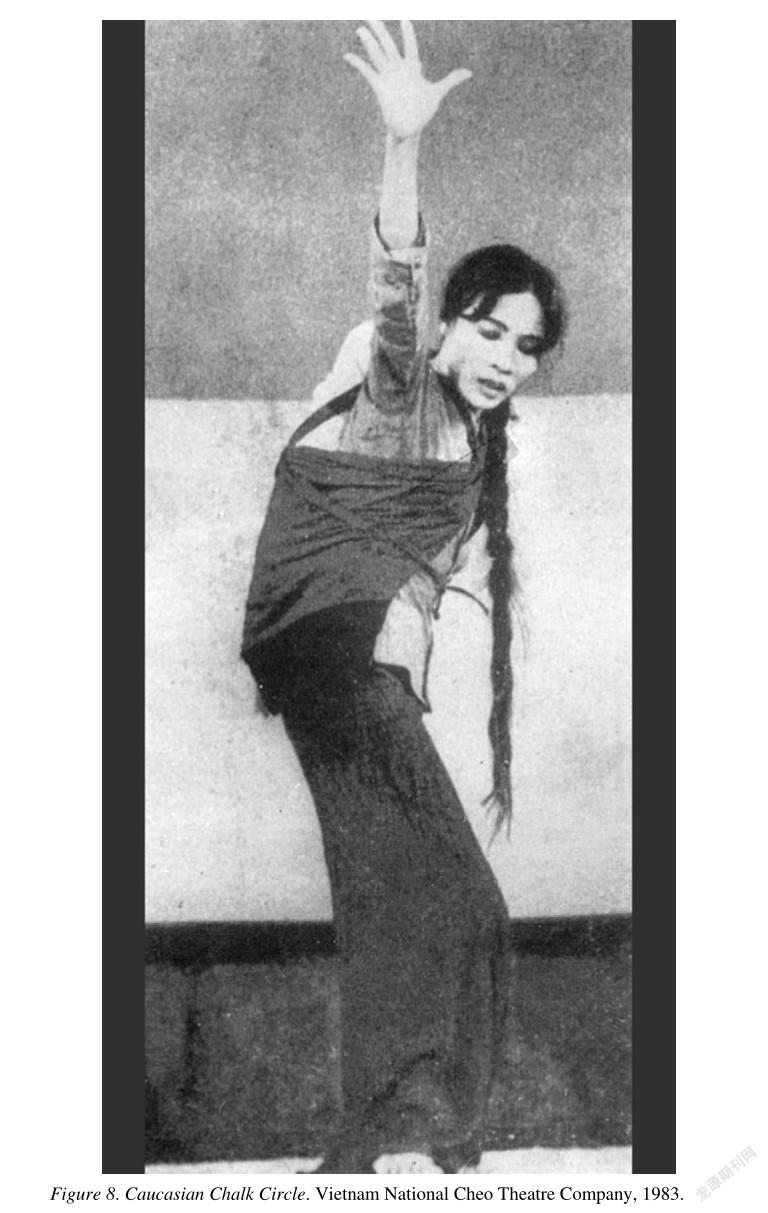

In this production a set of singers, placed at the side of the stage (as in Cheo), sang about how Grusha saves the child and persists in her moral decision despite hunger, cruelty and danger; simultaneously the actor playing Grusha dances with a series of “buoc xien” (a turn by moving feet together) to represent her strength of will (see Figure 8). These actions were harmonised with quick rhythm drum.

By quickly shifting positions of the rostra, the play’s scenes ran without black-outs. In this production of Caucasian Chalk Circle, all dramatic action was conducted in an open structure which consisted of 32 pieces narrated by the chorus. The prologue set up an unique tone for the whole play: farmers told the invited audience that they have arranged this performance to showcase their conflict over property ownership, hoping the audience’s comments would help them overcome the problem. Frequent subsequent appearances of the chorus reminded the audience of watching the farmer’s presence during the telling of the story.

With the participation of singers and musicians, Stillmark obtained a further alienation effect using traditional Vietnamese theatre forms—a combination of the hyper-realistic acknowledgement of theatricality and ethereal stylisation.

This production demonstrated how a contemporary story could be told using a traditional theatrical form. It suggested a practical answer to the question of how to modernise our traditional theatre, a long standing major concern of Vietnamese theatre practitioners. A report from Vietnam News on the 2005 Cheo Festival42 stated:“This year’s competition will discuss if Cheo has to be maintained in the traditional way or has to be made modern.”43 My answer is that it need to be modernised; more importantly my generation is obligated to find a strategy to make it fruitful. We seek a strategy to attract the audience’s attention to theatre, but it is a complicated issue with connections to areas such as economy, culture and education.

A Pointof Departure

One of the most significant aspects of multiculturalism throughout the globe is that it allows people from different cultures to identify themselves by showing their cultural differences. Cross-influences between various ethnic or linguistic groups in multicultural societies like Australia have been the source of cultural exchanges in which the existence of cultural or national communities remains recognisable.This has been achieved through mutual influences and without hiding behind their national identities.

However, this type of exchange is only possible when it is officially accepted by the political system in place. I have chosen to search for a context in which I could explore how a nation’s theatre culture is involved in the process of exchange with another nation. By seeking the underlying process for cultural exchange between nations, I expected to differentiate international exchange, rather than the processes of multicultural exchange within one national set of theatre practices.

Within the concept of theatrical internationalisation I hope to have provoked new thinking about theatrical practices of using elements from other theatre cultures, rather than the influences between ethnic groups or communities inside one nation.

References

Bang, T. (1998). French theatre and Vietnamese traditional theatre. The influences of French theatre on Vietnamese theatre culture(pp. 209-213). Hanoi: Theatre Institute.

Bang. T. (1999). An Overview on Cheo (p. 47). Hanoi: Theatre Institute.

Hanh, L. D. (1998). Cai Luong: Its national identity and modernisation. Vietnamese studies No. 4 (pp. 32-35). Hanoi: The Gioi Publishers.

Nghi, N. D. (1978). An interview with Nguyen Dinh Nghi about directing by Nguyen Thi Minh Thai. Theatre Magazine, (4).

Ngu, T. V. (1996). About Cheo (p. 277). Hanoi: Music Institute.

Quang, D. (1998). Asian theatre: Tradition and modernity. Vietnamese studies: Vietnamese theatre and other theatres of Asia (pp. 7-18). Hanoi: The Gioi Publishers.

Quang, D. (2004). The characteristics of Tuong , Cheo and their Prospects. Hanoi: Theatre Institute.

Quang, M. (1995). The characteristics of Tuong. Hanoi: San khau [Theatre].

Su, H. (2005). An application of stanislavsky’s method to actor training. Hanoi: Theatre Institute.

Thai, N. T. M. (2002). A memory of Nguyen Dinh Nghi. Theatre Magazine, (2).

Yen, X. (1998). Tuong in a new age. Hanoi: Theatre Publishing House.

Yen, X., Su, H.. & Ngu, T. V. (2000). The history of Vietnamese theatre (Vol. 3). Hanoi: Academy of Theatre and Film.

1 From the 13th-18th Centuries.

2 From the late 19th Century-1954.

3 According to Dai Viet su ky toan thu, an ancient book of Vietnamese History.

4 Before the 15th century, the official language in Vietnam was Chinese.

5 Such as Buddhism and Confucianism.

6 A well-known “Story of Kieu” was written by Nguyen Du in the 18th Century.

7 For example “Quan Am Thi Kinh”, “Truong Vien”, and “Kim Nham”.

8 Vietnam had been colonised by China for thousands years.

9 For example, a Cheo play “Kim Van Kieu” adapted from “A Story of Kieu” by Nguyen Du.

10 Such as verbal farce and verbal imitation.

11 It was written in 1672.

12 For example “Manh guong doi” (A Mirror of Life) by Tran Tuan Khai, “Co giao Phuong” (The Teacher Phuong) by Nguyen Ngoc Son.

13 For example Hang Bac Street Theatre, near Hoan Kiem Lake in the centre of Hanoi.

14 Xuan Yen, Hoang Su and Tran Viet Ngu. The History of Vietnamese Theatre. Vol. 3. Hanoi: Academy of Theatre and Film, 2000, p. 55.

15 Aristotle’s poetics.

16 For instance, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City Opera Houses.

17 For example, Truong Duy Toan, Vuong Hong Sen.

18 For example, “Luc Van Tien” by Nguyen Dinh Chieu.

19 During the 1920s-30s a number of visiting Chinese Sung drama groups from Guang Dong toured their productions to South Vietnam where many Chinese emigrated.

20 Like Ibsen, Meyerhold, and Vakhtangov.

21 In the speech given by a well-known scholar, Nguyen Tuan when he visited Moscow in 1988; mentioned in “An Application of Stanislavsky’s Method to Actor Training” by Hoang Su. Hanoi: Theatre Institute. 2005, p. 16.

22 And confirmed by my association and discussions with Hoang Su at the Hanoi Academy of Theatre and Cinema.

23 For examples, “Dai Doi Truong Cua Toi” written by Dao Hong Cam, directed by Dinh Quang (1975); “Doi Mat” written by Vu Dung Minh, directed by Dinh Quang (1976).

24 For example, Ngoc Phuong, Vu Minh, Doan Anh Thang, and Ngo Xuan Huyen.

25 For example, “The Issues of Acting”; and “The Art of Psychology—Realistic Acting” by Dinh Quang.

26 Cheo plays: “Tam Cam”, and “Luu Binh Duong Le”.

27 A Vietnamese metaphor about matching objects in a wrong way.

28 Plays such as “Mau chung ta da chay” (1962) written and directed by Tran Bang, National Cheo Theatre Company; and “Co Giai phong” (1964) written and directed by Tran Bang, Tao Mat and Ha Van Cau, National Cheo Theatre Company.

29 Inspired from the slogan: “To build a modern culture within strong national identity” decided by Vietnam’s government at the 6th Communist Party’s Congress in 1976.

30 Such as Nguyen Dinh Nghi, Nguyen Dinh Quang, and Ngo Xuan Huyen.

31 Decided by the government at the 8th Communist Party’s Congress in 1986.

32 They are both People’s artists.

33 Written by a famous contemporary playwright, Luu Quang Vu; performed by Vietnam National Theatre Company in Hanoi 1989, toured to the United States in 1998.

34 In Vietnamese traditional belief, dead people’s spirit remains alive.

35 For example, Doan Hoang Giang and Le Hung.

36 For example, “Nang Sita”, directed by Doan Hoang Giang, performed by Hanoi Cheo Company in 1989.

37 Such as modern music and set decorations.

38 For example, Pham Thi Thanh, Le Chuc and Le Hung.

39 For example, Doan Anh Thang and his Tuong production “Nguoi con gai Kinh Bac” (A Northern Girl” which was granted a Gold Medal at the National Theatre Festival in 1985.

40 Described as a “dialectical epic” to differentiate with Elizabethan Epic.

41 Directed by a German director, Alexander Stillmark; performed by Vietnamese Cheo actors in Hanoi, 1983.

42 Held annually in Ha Long City and from 7th to 17th September in 2005.

43 In Vietnam News’ review, a daily newspaper in English language, 07/09/2005.

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2021年5期

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2021年5期

- Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- A Brief Examination of India-Africa Relations in the Western Colonial Period

- A Study on Advertisements in The Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal

- Research on the Ideological Origin of the Initial Period of Robot Animation in Japan

- Blinding Lights:the Creative Queer Geography of Daniel Nolasco’s Dry Wind

- Review on the Development of Evidentiality and Analysis of Non-Grammatical Evidential Systems

- The Application of Cohesion and Coherence Theory in Advanced College English Teaching