Tree mortality and regeneration of Euphrates poplar riparian forests along the Tarim River,Northwest China

Ayjamal Keram,Ümüt Halik ,Tayierjiang Aishan,Maierdang Keyimu,Kadeliya Jiapaer and Guolei Li

Abstract

Keywords:Tree mortality,Regeneration strategy,Seedling and sapling recruitment,Gap makers,Riparian forest,Tarim River

Highlights

· Effect of hydrological alterations on tree mortality of Populus euphratica riparian forest was quantified.

· The contribution of different habitats (canopy gap area, undercanopy area and riverbank area) on plant regenerations was evaluated.

· Recommendations for regeneration and succession of riparian forests at the Tarim River were put forward.

Introduction

Riparian forests provide fundamental ecosystem services in arid regions, including maintenance of ecological stability and prevention of natural disasters such as sandstorms, heatwaves, and desertification (Song et al. 2000;Chen et al. 2013; Betz et al. 2015; Mamat et al. 2018;Halik et al. 2019). The existence of trees, bushes, and grass vegetation on the banks of the Tarim River, which constitute the natural barriers of river oases, is absolutely dependent on the river (Zeng et al. 2002, 2006;Halik et al. 2006; Aishan et al. 2018). In recent decades,floodplain vegetation has been threatened by increased water scarcity, and large areas of riparian forests including seedlings and saplings, have withered (Gries et al.2003; Foetzki 2004; Aishan 2016; Zeng et al. 2020). With China’s rapid economic development and the implementation of the “Ecological Civilization” and “One Belt One Road” initiatives, the ecological restoration of the floodplain ecosystem along the Tarim River has been designated as a high priority by the Chinese government(Halik et al. 2006, 2019). Conservation of the remaining riparian forests and recovery of the degraded parts of the ecosystem are crucial for further sustainable development of the region (Rumbaur et al. 2015; Deng 2016;China Green Foundation 2018), particularly, transport infrastructure, including railways, highways, and oil and gas pipelines in the Tarim Basin are in need to be protected (Deng 2009, 2016; Aishan 2016; Halik et al. 2019).Thus, it is necessary to preserve the functions and services of these forests through adaptive management.

The riparian forest (also known as Tugai forests) at the Tarim River constitute a natural green belt at the northern edge of the Taklimakan Desert. The Euphrates poplar(Populus euphratica Oliv.)is a dominant tree species in the floodplain ecosystems. As a “Green Corridor”,P. euphratica forests have become increasingly important for preventing the unification of two neighboring sandy deserts, the Taklimakan and the Kuruktagh (Xu et al. 2006; Betz et al. 2015). These forests have important ecological functions in addition to socio-economic and touristic value, such as protection of biodiversity,regulation of the climate and hydrologic conditions in oases, fertilization of soils, and maintenance of regional ecosystem balance (Wang et al. 1995; Huang 2002;Huang and Pang 2011; Mamat et al. 2019). Nevertheless,the Tarim floodplain ecosystem, especially the riparian vegetation, has been seriously degraded, as the water conveyance in the main channel has rapidly decreased and many tributaries of the watershed have been disconnected from the main river (Zhao et al. 2011; Chen et al.2013).

Many studies have demonstrated that water shortages in the Tarim are mainly caused by climate change coupled with intensive anthropogenic activities, i.e., tree felling, overgrazing, excessive land reclamation and disorderly expansion of cotton monoculture. Therefore,restoring degraded floodplain ecosystems has become a major focus of applied forest research (Deng 2009; Rumbaur et al. 2015; Thomas et al. 2017; Thomas and Lang 2020). Among all processes of natural forest dynamics,the formation of forest canopy gaps was considered a vital regeneration strategy for maintaining floodplain forest structures (Han et al. 2011; Keram et al. 2019).Gap disturbance is the main driving force of forest dynamics as it creates environmental heterogeneity (Zhu et al. 2003, 2007; Albanesi et al. 2005; Bottero et al.2011). Forest gaps thus create important habitat for the regeneration of plant species, which may otherwise be suppressed by the undercanopy (Han et al. 2011; Sharma et al. 2018). They also play a vital role in forest regeneration and succession, especially in the establishment and development of plant species that differ in ecological recruitment (Runkle 1998; Mountford 2006; Rentch et al.2010; Han et al. 2013; Zhu et al. 2014; Jankovska et al.2015).Nagel et al.(2010)reported a high presence of advanced regeneration in a gap regeneration study of a(mixed) beech virgin forests. Besides, it also has been reported that canopy gaps close when the height of regenerations reached 20 m, consistent with the definition used by Nagel and Svoboda (2008). Zhu et al. (2021)found that with the decreased of gap size, pioneer species became the sub-canopy layer, and with the aging of gap, the light conditions changed over time, which was conductive to the recruitment of shade-tolerant species;Keram et al. (2019) also revealed that hydrological conditions (groundwater, runoff and water consumption)are the main driving force of the gap-scale disturbance of desert riparian forests along the Tarim River. In floodplain forests, canopy gaps may not be filled with regenerations within a short period because of high tree mortality. This leads to the continual expansion of canopy gaps (Keram et al. 2019). The majority of earlier studies have focused on the mortality of gap makers and the diversity of regeneration species in other various climatic zones, such as tropical, subtropical, north temperate, and cold temperate regions (Runkle and Yetter 1987; Yamamoto 2000; Dorotä and Thomast 2008;Petritan et al. 2013; Popa et al. 2017; Zhu et al. 2018;Kitao et al. 2018). However, systematic research on tree mortality and plant regeneration of desert riparian forests under various hydrological scenarios are relatively lacking. Therefore, it is necessary to scientifically understand the response of P. euphratica mortality rate to hydrological dynamics at regional scales, and seedling and sapling regeneration in the Tarim River Basin.

Forest canopy gaps may provide opportunities for species regeneration and have therefore been widely exploited in forest recovery programs (Coates and Philip 1997; Schliemann and Bockheim 2011; Kern et al. 2013,2017; Nagel et al. 2016; Lu et al. 2018). Thus, it is necessary to conduct studies to better understand the mortality of gap makers under long-term hydrological processes and seedling and sapling establishment in different habitats, such as canopy gap areas (CGAs), undercanopy areas (UCAs), and riverbank areas (RBAs) of floodplain, as well as to clarify the contribution of canopy gaps to plant regeneration in riparian forests. Such information may provide insights into the efficiency of gap usage and seedling planting in forest restoration activities along the Tarim River. In the present study, we used comprehensive field investigation data to describe tree mortality as well as to compare the density of seedlings and saplings between the CGAs, UCAs, and RBAs to evaluate whether the CGAs are important for the regeneration of P. euphratica riparian forests along the Tarim River.In this work we made three hypotheses:

(H1)

Based on the observation that canopy gap disturbances have frequently emerged in the desert riparian forests and its composition and structure were drastically different from other forest types (Han et al. 2011; Keram et al.2019). We hypothesized that characteristics of tree mortality (number, DBH) strongly responded to hydrological dynamics (such as stream flow) at local and regional scales in the Tarim River Basin, resulting in the emergence of special forest gap structures.

(H2)

Conclusions on the size development of canopy gaps,once formed they would continuously expand (Keram et al. 2019). The important process of gap dynamics,i.e. plant regeneration, in floodplain forests has not been quantified yet. To test the general hypothesis,that canopy gaps promote plant regeneration in riparian forests, we formulated the hypothesis that canopy gaps drive tree regeneration to some degree, due to canopy gap provides more adequate light conditions than the UCAs.

(H3)

In floodplain forests, due to the degradation of plant habitat, canopy gaps may not be filled up with other regenerations in a relatively short period. By comparison of the species diversity between gap makers and gap fillers in canopy gaps, we hypothesized that canopy gaps may not be filled up with other regenerations within a short time, (i) which may be due to the degraded habitat of plant growth, (ii) prolonged and unexpected flooding disturbance resulted in the degradation of P. euphratica trees, and (iii) its mortality did not cause significant changes in tree distribution but caused changes at tree level.

We intend to verification of these hypotheses by compiling data from six permanent monitoring plots located at undisturbed natural forest sites along the middle reaches of the Tarim River. We believe that addressing these hypotheses will contribute to improve the understanding of the current state of the Tarim riparian ecosystem, where P. euphratica is now in urgent need of protection. Additionally, it will provide an ecological framework for the design and implementation of closeto-nature restoration techniques to extend P. euphratica forests.

Methods

Study site

Field work was conducted in Yingbazha village (41.22°N,84.31°E, ASL 1000 m) in Tarim Huyanglin Nature Reserve (THNR) along the middle reaches of the Tarim River (Fig. 1), which was established in 1984 and upgraded to a National Nature Reserve in 2006. The region is an extremely arid warm temperate zone, with an annual mean precipitation of 75 mm and an annual mean temperature of 11.05°C (Keyimu et al. 2018). The annual potential evapotranspiration ranges from 2500 to 3500 mm (Rouzi et al. 2018). According to the USDA(United States Department of Agriculture) soil classification system, the soil of the Tarim River is a member of the Aridisol order, and the soil is silty loam (Hu et al.2009; Yu et al. 2009). The local groundwater system is recharged from the surface water through bank infiltration(Huang et al. 2010). The forest structure and composition in the study area is relatively simple, and the local flora is mainly composed of P. euphratica, Tamarix ramosissima and Phragmites australis (Table 1). However, a few rare plant species are also present, including Populus pruinosa,Tamarix hispida,Tamarix leptostachys,Glycyrrhiza glabra,Inula salsoloides, Karelinia caspica, Lycium ruthenicum,Alhagi sparsifolia, Apocynum venetum, Halimodendron halodendron, Poacynum hendersonii, Cirsium segetum,Cynanchum auriculatum, Aeluropus pungens, Taraxacum mongolicum, Salsola collina, Calamagrostis pseudophragmites, Myricaria platyphylla, Halogeton glomeratus, and Elaeagnus oxycarpa (Gries et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2004;Thevs 2006; Thevs et al. 2008; Huang et al. 2010; Lang et al.2016;Halik et al.2019).

Fig.1 Sketch map of the study area

Field investigation

A complete field survey was carried out from May 15 to June 20, 2017. A total of 60 canopy gaps were investigated in six replicate grid plots (50 m×50 m) (Table 1).Canopy gaps were created by tree mortality (i.e., death)or by >50% loss of tree branches. The ratio of gap diameter to tree height on the border of the gap (RD/Hvalue)ranged from 0.4 to 2.2 (Keram et al. 2019), which is consistent with measurements reported by Zhu et al. (2015).For each canopy gap, all surrounding trees and gap makers were identified, and the species, diameter at breast height (DBH), and tree height (TH) or log length were recorded for each tree. Morphological characteristics were used to determine the degree of tree decomposition and the life expectancy of gap makers was estimated under the guidance of local experienced forest workers (Liu and Hytteborn 1991; Droessler and Von 2005; Thomas and Jurij 2006; Petritan et al. 2013; Wen 2016; Yang et al. 2017; Keram et al. 2019), and the relative ages of the gap makers were thus determined. In addition, we determined whether there were significant differences in the DBH distribution among living and dead trees. We regarded trees bordering canopy gaps as living trees and gap makers as dead trees. To investigate regeneration species, we selected five replicate plots in each habitat (CGAs, UCAs, and RBAs) and recorded the species and numbers of seedlings and saplings. We simultaneously compared the species diversity and densityin these plots. We defined a CGA as an area where the canopy gap >10 m2. For the UCA, we chose plots around the canopy gaps in the study area; RBA plots were located near the riverbank, which were covered with excessive water. For each habitat, 15 repeated sampling plots (10 m×10 m) were set, giving a total of 45 sampling plots. In each plot, we counted the number of species, for seedlings (≤10 cm tall) and saplings (10–100 cm tall) (Walker 2000).

Table 1 Characteristics of six natural stands sampled for analysis of tree mortality

Data processing

Classifying the DBH structure of gap makers

Over the entire area of canopy gaps, gap makers were classified into five categories according to their DBH and TH (Xu et al. 2016): Class I comprised juvenile trees(DBH <5 cm, TH <4 m), Class II comprised young trees(5 cm <DBH <10 cm, TH ≥4 m), Class III comprised young/middle-aged trees (10 cm <DBH <15 cm), Class IV comprised middle-aged trees (15 cm <DBH <20 cm),and Class V comprised old trees (DBH >20 cm).

Dynamic index of gap maker structure

The dynamic structure of gap makers was quantitatively analyzed. The dynamic index of population structure(VPi) can be represented by the change trend of gap makers in various structures. If 0 <VPi≤1, the quantity of gap makers increased with the VPivalue; If -1 <VPi≤0, the quantity of gap makers decreased with the VPivalue. The dynamic index of gap maker individuals (Vn)without external disturbance is described by the following equation:

where Snis the number of individuals in n DBH class,Sn+1is the number of individuals in n+1 DBH class of gap makers, and (…)maxis the maximum value in the column. Below is the formula used to calculate the dynamic index of gap maker structure (VPi):

where Snand Vnare the same as in Eq. (1), K is the quantity of gap makers in different age classes, and the range of VPiis consistent with Vn. We used the formula proposed by Chen (1998) to calculate the dynamic index value under completely random (Vpi’) and non-random(Vpi′′) disturbances.

Statistical analysis

We have calculated species diversity according to the Margalef richness index and Shannon Wiener index (Ma 1994; Ma and Liu 1994). A fitting optimization t-test method was used to statistically analyze the change trend of gap makers that died in different years and to evaluate the distribution patterns of the DBH values of gap makers. We used a chi-square goodness-of-fit test to reveal the DBH distribution of dead trees versus living trees. Further, we comparatively analyzed plant regeneration density between the different habitats (CGAs,UCAs, and RBAs) using the Margalef and Shannon-Wiener indices. Values of P <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The data were organized using Excel 2015 (Microsoft, Redmond, USA) and analyzed using OriginPro 2016(OriginLab Corp2016).

Results

Tree mortality

Among the 245 gap makers identified, the mean DBH was 20.80±9.03 cm (range 10.10–49.50 cm) and there were significant variations in different years. The chisquare goodness-of-fit test showed that the DBH structure of gap makers presented a common curve distribution (Fig. 2). The DBH distribution of gap makers approximated a Gaussian fit (R2=0.762, 0.749, 0.829,0.896, 0.918, and 0.364, respectively; P <0.05). However,large young gap makers (DBH <15 cm) were more common in the study area, especially in the 2007–2016(Gaussian fit, R2=0.364, P <0.05). During the investigation, we found that some young trees were injured or crushed by old trees.

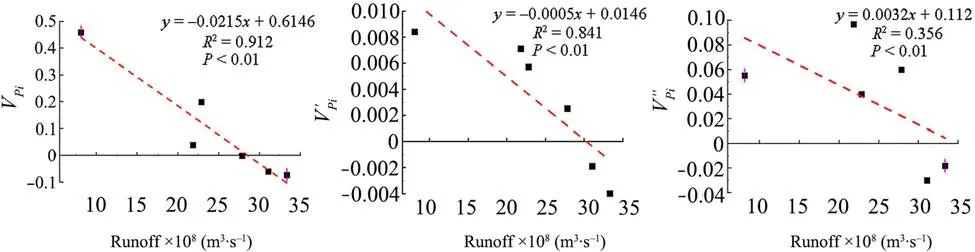

In this study, we found that stream water was significantly negatively correlated with tree mortality rates over the last three decades. Based on the above data analysis,there was an ascending trend in the dynamic index of gap maker’s population structure during the periods of 1977–1986, 1987–1996, 1997–2006, and 2007–2016,while in 1957–1966 and 1967–1976 there was a descending trend (Table 2). Furthermore, there was a considerable negative interaction between the dynamic index value of gap maker population structure and annual runoff; the equation of the fitted model was y=-0.0215x+0.6146 (R2=0.912, P <0.01) without external disturbances (Vpi), while the equation of the fitted model was y=-0.0005x+0.0146 (R2=0.8405,P <0.01) under completely random disturbances (Vpi′)and y=0.0032x+0.112 (R2=0.356, P <0.01) under non-random disturbances (Vpi′′). Vpiand Vpi′ decreased markedly with increase of stream runoff in the study area(Fig. 3). The Vpi′ value became positive and tended to increase when the river dropped to 25.86×108m3.

Comparison of the DBH distribution of dead trees and living trees showed significant variation with a high proportion of young dead trees (Fig. 4). As mentioned above, the trees surrounding CGAs and gap makers represented living trees and dead trees,respectively. Grid chart analysis showed that the median DBH of dead trees, especially those died before 1996, were larger than that of living trees. However, by comparing DBH, we found that the trees that died in the 1997–2016 were smaller than living trees.

Fig.2 Diameter class distribution of P.euphratica gap makers in the study area

Forest regeneration

Riparian vegetation was distributed on both sides of the riverbank and was relatively simple and sparse in structure. In our field investigation, we counted 23 seedling and sapling species belonging to 12 families and 20 genera. In general, there were obvious differences in seedling and sapling regeneration among the habitats(CGAs,UCAs, and RBAs)(Table 3).Among the 14 plant species found in the CGAs, 7 were also found in the UCAs and 19 were also found in the RBAs; P. euphratica, T. ramosissima, T. hispida, T. leptostachys, G. uralensis and E. oxycarpa commonly appeared in all three habitats. P. pruinosa, P. hendersonii, C. segetum, C. auriculatum, A. pungens, T. mongolicum, M. platyphylla and L. ruthenicum were rare species, which only appeared in the RBAs. P. australis, H. halodendron and A. sparsifolia grew in the CGAs, but not in the UCAs or RBAs.Additionally, the RBAs contained a high number of P.euphratica species (30) compared to other habitats, and the number of P. euphratica and other species in the CGAs was higher than in the UCAs.

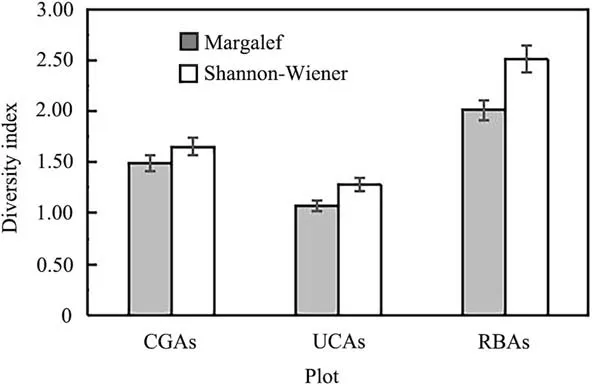

The seedling and sapling density of P. euphratica was significantly higher in the RBAs than in the CGAs and UCAs. However, compared with the UCAs, the CGAs promote tree regeneration to some extent by providing favorable conditions for the survival and growth of seedling and saplings (Table 4). We also performed quantitative analysis of seedling and sapling regeneration, based on species diversity and richness (Fig. 5). According toanalysis of the Margalef and Shannon-Wiener indices,the species diversity of seedlings and saplings was remarkably higher in the RBAs than in the other two areas,and higher in the CGAs than in the UCAs(P <0.05).Further,though the density and diversity of seedlings and saplings in the CGAs was not as high as in the RBAs,the survival rate of young trees was higher in the CGAs than in the RBAs(Table 4).

Table 2 Analysis of population structure dynamics of gap makers under different volumes of runoff water

Fig.3 Relationship between population structure dynamics of gap makers and annual runoff

Comparison of gap makers and gap fillers

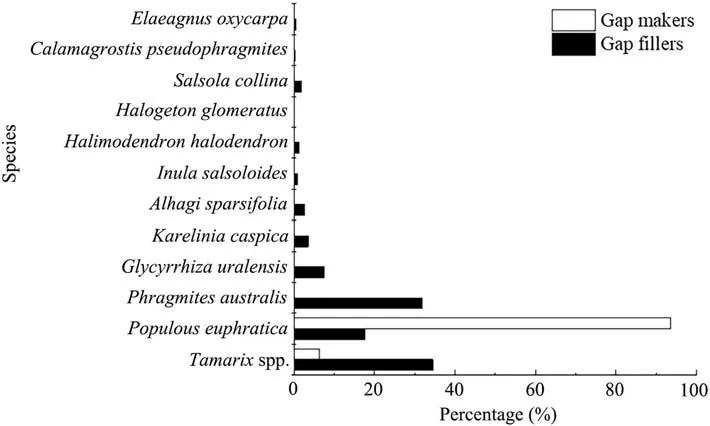

The statistical analysis showed that P. euphratica is the most common species of gap maker. However, it also existed as gap filler, along with T. ramosissima and P.australis (Fig. 6). Other gap fillers included P. pruinosa,A. venetum, H. halodendron, P. hendersonii, C. segetum,C. auriculatum, A. pungens, T. mongolicum, S. collina,C. pseudophragmites, M. platyphylla, H. glomeratu and E. oxycarpa, as well as some herbs such as G. glabra, I.salsoloides, K. caspica, L. ruthenicum, and A. sparsifolia,although they were very rare.

Discussion

Fig.4 Boxplots of the DBH of dead trees and living trees on the grid charts in canopy gaps that were created at different times.The boxencloses the middle 80%of observations. Median and mean values are indicated by a vertical line(-) and a star(★),respectively.The upper whisker indicates the largest DBH value,while the lower whisker shows the smallest.The plus sign(+)indicates the maximum DBH

Table 3 Seedling and sapling recruitment in different habitats in the study area

One or more gap makers, i.e., dead trees, create canopy gaps in forests (Zang et al.1999). Keram et al. (2019)found that the mortality of gap makers did not substantially contribute to increased gap size in floodplain forests along the Tarim River. This could be explained by the small crown and DBH of gap makers. Tree mortality is caused by different agents, including drought or flooding, strong wind, diseases, and insect pests, and affects forest dynamics (Krasny and Whitmore 1992; Battles and Fahey 2000). Host-specific disturbance was considered to be the most common agent of tree mortality in old-growth mixed beech forests in the Western Carpathians (Orman and Dorota 2017), while wind disturbance led to a disproportionate number of gap makers in old-growth red spruce–Fraser fir forests in North Carolina (White et al. 1985) and red spruce–balsam stands in New Hampshire (Foster and Reiners 1986;Worrall et al. 2005). However, the causes of tree mortality in riparian forests are different from those in other forest types, such as tropical and subtropical forests. The results of the present study showed that tree mortality in riparian forests along the Tarim River was mainly influenced by hydrological factors (surface water), although strong winds or insect pests may also play a role (Han et al. 2011).

Water is the most important limiting factor for the maintenance and growth of P. euphratica in arid ecosystems, and P. euphratica depends on ground water that available to its roots (Yu et al. 2019). It is known that water is the factor with most influence on the survival,distribution, and development of vegetation in hyperarid regions. In arid ecosystems,the vitality of P. euphratica forests strongly depend on the groundwater level(Halik et al. 2006, 2009; Wang et al. 2008; Ginau et al.2013; Keyimu et al. 2017). Halik et al. (2019) reported that the vitality of P. euphratica diminished when the groundwater level was not sufficient for the development of tree stands. In addition, Xu et al. (2016) studied the correlation between groundwater and surface water using stable isotope technology. Their results indicated that the groundwater level is significantly affected by surface water. Chen et al. (2004) and Keilholz et al.(2015) also demonstrated that groundwater is often supplied by stream flow and infiltration from watercourses.The groundwater depth in the Tarim Basin has dropped continuously as a result of the desiccation of streams and decreases in stream flow since an embankment was built in 2000. Thus, the physical characteristics of plant habitats have been changed. Consequently, the growth of P. euphratica cannot be sustained as before in this region, and forests have highly degraded or died. According to the present study, hydrological alterations may be the main cause of tree death in desert riparian forests along the Tarim River. DBH is one of the most common forest inventory variables and can reflect the population structure and growth status of tree stands (Condit et al.2000; Di et al. 2014). Due to the unique climate and habitat conditions of desert floodplain areas, tree shape variables are obviously different from those in temperate or/and subtropical forests (Ling et al. 2015). In the present research, it was found that most young gap makers (DBH <15 cm) died in the most recent two decades, i.e., 1997–2006 and 2007–2016. In the early 1970s, water resources were affected on a regional scale by climate change and anthropogenic activities (increased water use for irrigation), and then lag effects led to a progressive decrease in surface water from 1984 and caused a reduction in groundwater from 2004 (Keram et al. 2019). This resulted in habitat deterioration and adecline in the survival of young P. euphratica individuals. Based on quantitative correlation analysis, the present study revealed that gap maker mortality and DBH structure responded negatively to variations in surface water. This may be due to long-lasting exogenous disturbances, such as a scarcity of surface water or a decrease in groundwater level, having a notable influence on vegetation through drought stress. Thus, the water requirement of riparian vegetation was not satisfied.Therefore, gap makers of low DBH appeared frequently in P. euphratica forests, which experienced an increase in more resilient species. This may be because the vitality of P. euphratica in this arid area was directly affected by the hydrological conditions, and only a small proportion of young trees survived to reach canopy height.However, there were a large number of larger, mature trees among the living trees that have developed root systems and are therefore not significantly affected by the reduced groundwater level.

Table 4 Comparison of P.euphratica seedlings and saplings in different habitats in the middle reaches of the Tarim River

Fig.5 Species diversity of seedlings and saplings in different habitats

Fig.6 Comparison of gap maker and gap filler species in the middle reaches of the Tarim River

By creating environmental heterogeneity in terms of light availability, gap disturbances play a key role in forest regeneration as well as in the establishment and development of tree species with different ecological recruitment patterns (Runkle 1989; Peterken 1996;Mountford 2006; Zhang et al. 2006; Li et al. 2013). Gapbased restoration provides a flexible system that emulates natural regeneration under different environments. Van and Dignan (2007) reported that seedling and sapling diversity and richness were promoted by light intensity. Zhu et al. (2014) stated in a review of published studies that compared to UCAs, the seedlings and saplings of shade-tolerant species have significantly higher density in CGAs. Overall, water, light availability,and seedbed conditions potentially affect seedling emergence, germination, and establishment in floodplain riparian forests. It was found that appearance of seedling is closely related to flooding patterns in this study. Besides, a higher density of seedlings and saplings is expected in gaps as they provide full light conditions. The results of the present observations showed that the seedling and sapling species diversity was higher in the CGAs than in the UCAs. Hence, forest canopy gaps playing a pivotal role in the long-term germination and regeneration of plant species in some degree. Oliver and Larson(1996) stated that canopy gaps simultaneously result in mortality in some individuals and establishment and growth in others, and the ongoing process of death and replacement has a profound effect on forest structure and composition. Pham et al. (2004) showed that Abies balsamea is the most frequent successor in Abies forest stands and that Picea mariana is the most likely replacement species in Picea forest stands, regardless of the species of gap makers. In the present study, canopy gaps were filled with shrubs and herbs. When we examined the probability of replacement in floodplain forests,there seemed to be a reciprocal replacement of P.euphratica by T. ramosissima. and P. australis (Fig. 6). However, the probability of P. euphratica replacement was lower when the mortality of young trees was particularly high.

Conclusion and suggestion

As the largest riparian forest ecosystem in Northwest China, Euphrates poplar forests are facing great challenges of climate change and human interference (Zhang et al. 2016; Halik et al. 2019). Monitoring of tree mortality and plant regeneration in different habitats is considered the most effective way of ensuring the sustainable regeneration and ecological restoration of floodplain forests along the Tarim River. Based on evaluation of the correlation between tree mortality and water resources in the study area, hydrological conditions (runoff volume) are the main reason for the death of P. euphratica forests. At the beginning of the 1970s, hydrological conditions were affected on a regional scale by anthropogenic activities. Consequently, riparian forests were threatened under water scarcity, which resulted in high mortality among Populus species. Our observations of seedling and sapling density indicated that the frequency of plant species was different among the three studied habitats; it was highest in the RBAs, intermediate in the CGAs, and lowest in the UCAs. It may have been affected by light availability and hydrological conditions during seedling and sapling recruitment.

In conclusion, searching the tree mortality and plant regeneration are considered to be the most effective ways to clarify the development trend of desert riparian forest. Furthermore, the protection and maintenance of the floodplain vegetation along the Tarim River are crucial to sustainable regional development in the Tarim Basin. Our study area is located in the Yingbazha section, where there are fragment pits of stagnant water by flooding. Moreover, though the density and diversity of seedlings and saplings in the CGAs was not as high as in the RBAs, the survival rate of young trees was higher in the CGAs than in the RBAs. Accordingly, we suggest that making full use of limited resources of stagnant water pits to establish a “Natural Nursery of the Poplar”and appropriately transplanted into the gap, the main purpose of which is to achieve an improved regeneration efficiency of the Populus euphratica riparian forests.Additionally, there is a need for further applied experiment to establish test areas for flood water allocation and utilization strategies, which, if successful, should then be extended to the whole basin. Thus, we argue that, to some degree, canopy gaps can provide a favorable environment for seedlings to grow into saplings,thereby reaffirming the importance of gap creation for forest regeneration.

Abbreviations

DRB: Distance from river bank; GWL: Groundwater level; DBH: Diameter at the breast height; TH: Tree height; CGAs: Canopy gap areas;UCAs: Undercanopy areas; RBAs: Riverbank areas; THNR: Tarim Huyanglin nature reserve

Acknowledgments

Cordial thanks to MSc-Students (Elyar, Wang Wenjuan, Ramile, Mihray and Gao Qing) from the Xinjiang University for their intensive support during the field investigation. Special thanks to Xinjiang LIDAR Applied Engineering Technology Research Center for giving us free use of the Riegl VZ-1000 Terrestrial Laser Scanner. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments that greatly helped us improve the quality of this manuscript.

Authors’contributions

Ayjamal Keram conceived, designed and performed the experiments,contributed the data collection, analyzed the data, prepared figures and tables, and authored or approved the final draft of the manuscript. Ümüt Halik conceived and designed the experiments, contributed the data collection, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final draft. Tayierjiang Aisahan, Maierdang Keyimu and Kadeliya Jiapaer participated in field work,contributed the data collection/validation and language proofreading. Guolei Li edited and validated the manuscript with critical comments and reviewed the manuscript draft.All authors checked and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(31860134, U1703102, 31700386).

Availability of data and materials

The data set generated for the study area is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author details

1College of Resources and Environmental Science, Key Laboratory for Oasis Ecology of Ministry of Education,Xinjiang University, Ürümqi 830046, China.2College of Forestry, Key Laboratory for Silviculture and Conservation of Ministry of Education, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing 100083, China.3State Key Laboratory of Urban and Regional Ecology, Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100085,China.

Received: 26 February 2021 Accepted: 9 June 2021

- Forest Ecosystems的其它文章

- Effects of harvest intensity on the marketable organ yield,growth and reproduction of non-timber forest products(NTFPs):implication for conservation and sustainable utilization of NTFPs

- Reduced turnover rate of topsoil organic carbon in old-growth forests:a case study in subtropical China

- Introduction of Dalbergia odorifera enhances nitrogen absorption on Eucalyptus through stimulating microbially mediated soil nitrogen-cycling

- Assessing a novel modelling approach with high resolution UAV imagery for monitoring health status in priority riparian forests

- Solar radiation effects on leaf nitrogen and phosphorus stoichiometry of Chinese fir across subtropical China

- Effect of thinning intensity on the stem CO2 efflux of Larix principis-rupprechtii Mayr