THREADS OF LIFE

By Sudeshna Sarkar

When I was young, a film made in Bollywood movie industry became famous, not so much for its content but for the title, which remains on peoples lips even now. The title, Roti, Kapda Aur Makan, sums up the three basic necessities of life—food, clothing and shelter.

Almost five decades later, when I came to work in China, I saw the catchphrase resurrected. China hurtled through last-mile hurdles to announce on November 23 that it had eradicated absolute poverty and the measures taken included ensuring these three basic necessities, as well as a few other essentials, like education and healthcare.

To see for ourselves how these measures have worked, we went to places that ensured food security for the nation and also to new residential communities for people who earlier lived in inhospitable and opportunity-less areas so that they have access to better livelihood.

The last stop on our travels was clothing, which opened up an entirely unknown world to me.

On a sunny day in November, we arrived at the Beishan Primary School in Sanya, Hainan Province, south China. We were there to attend an early morning class that taught an unusual subject—weaving. The small school with four grades and only 32 students was built for the neighborhood where the people were mostly from the Li ethnic minority group.

The Li people in Hainan are historically renowned for their weaving skills. While we waited at the gate, I admired the paintings on the wall that showed people making textiles, mostly women.

Women power

Traditional textile making in China was a female stronghold, the art passed on by women to their daughters and granddaughters. In the 13th century, a young woman, who later became known as Huang Daopo, arrived in Hainan. She was a runaway who had fled Songjiang, now Shanghai, because of her in-laws ill treatment. The Li community embraced her and taught her their art and soon she became adept at spinning and weaving.

Then Huang went back to her hometown with her head held high and began to teach her skills to local women. As an icon of traditional textiles industry, she has been the subject of a documentary and her fame has spread as far as the planet Venus, where a crater is named after her.

At the school, the class was a picture to behold. Ji Julian, the head weaving teacher, and her assistants were dressed in traditional Li clothes, a dark blouse and skirt brightened by amazing and intricate embroidery in vivid colors and an equally vivid headdress. The young students also wore traditional clothes in red. They sat on the floor with the loom on their lap, one end of it held by their toes and the other wrapped round their waist.

It was physically challenging, requiring a strong back to stay straight for hours without any support and having to constantly bend forward, which made me realize why hand-woven textile is so expensive. Ji said it is a matter of practice. Her 70-year-old mother is still weaving.

Ji, who has her own studio nearby, has been recognized as an inheritor of intangible cultural heritage. Last year, she went to Paris to attend a UNESCO exhibition on intangible cultural heritage. Her studio, started in 2017, has 14 women working there, making traditional articles like headdresses and embroidered accessories.

Ji learned the art watching the women in the family, her grandmother, mother and aunts. However, yarn was an expensive commodity at that time and the children were not allowed to use it. They had to be content making their own thread out of coconut leaf strips. Once, when her mother caught her using the loom, she was given a sound spanking, which she remembers even now.

The cotton industry in China has undergone a sea change since Jis childhood. And her students dont need to worry about the supply of yarn thanks to the growth of Chinas cotton industry.

Coming full circle

Liu Ji, who is with the breeding center of the Cotton Research Institute under the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), gave us a global and historical perspective.

The first cotton seeds, Liu said, came to China from India and Southeast Asia along the ancient Silk Road. It was a struggle to clothe the population in the early days after the founding of the Peoples Republic of China in 1949 and the first cotton experts were sent to Sanya in 1959 to develop improved cotton seeds.

Earlier, researchers had been trying to do this in other provinces with a warm temperature and after three years of research, they finally found the best place for cotton breeding in Sanya. I found it a matter of destiny, or yuanfen in Chinese. The area they chose, Yacheng, was where Huang had found her calling. The high temperature year round and little rain in winter make Yacheng an ideal cotton nursery.

Like most pioneers, the cotton researchers had a tough life. There was only one railway to Sanya at that time and the train was slower than a car, carrying both passengers and cargo. China went through natural disasters from 1959 to 1961 and food was scarce. The researchers had to scrounge for vegetables growing in the wild to assuage hunger.

In 1982, a permanent cotton breeding base was established in Sanya under CAAS. In the next two decades, 280 new varieties of cotton had been cultivated.

Two milestones stand out. One was the cultivation of a new hybrid that has both high yield and pest resistance. This followed after a pest disease struck cotton plantations in the 1990s and spread to corn and vegetables. By 1993, six new insect-resistant varieties had been bred.

The other has a direct bearing on Chinas environmental protection and its commitment to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060. In the past, the cotton industry used mulching technology, covering the plants with a plastic film to prevent damage by low temperature or drought. However, the plastic was hard to dispose of and a contributor to pollution.

To address this, one of the pioneer researchers, Yu Shuxun, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, developed a variety that made it possible to ditch the films.

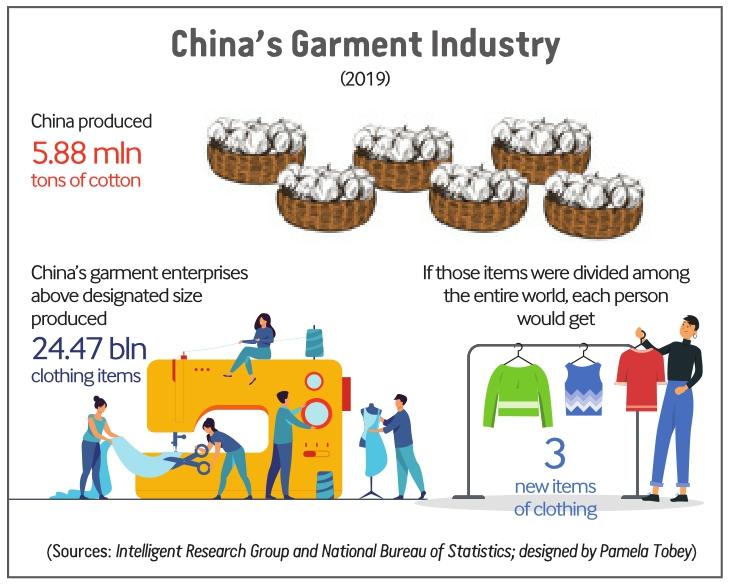

Today, China is the largest producer of cotton, with the output reaching 5.89 million tons in 2019. According to Beijing-based Intelligence Research Group, that same year, Chinese garment industries above designated size—industrial enterprises with an annual business turnover of at least 20 million yuan ($2.82 million)—alone produced nearly 24.5 billion items—enough to provide the entire global population with three articles each.

New Cotton Road

According to Liu, cotton used to be also grown in Chinas Yangtze and Yellow River basins. However, the main industry has now shifted to Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region because of its suitable climate while Hainan is the main research and development base. “Cotton has become a major industry in Xinjiang, helping farmers come out of poverty and improving the quality of life,” Liu said.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, China imported 1.94 million tons of cotton in 2019. However, Liu foresees a new cotton industry belt starting out from Xinjiang, providing an option in the future. Cotton seeds developed in China are being planted in Central Asia as part of the Belt and Road Initiative and he thinks this new industrial belt could one day become global exporters.

More than 2,000 years ago, the Silk Road connected Asia and Europe, fostering trade, cultural exchanges and people-to-people contacts. Today, a new Cotton Road is taking shape, creating common development.