Seeds of Hope

By Sudeshna Sarkar

What is common to dinosaurs and the minuscule rice? Why do you feel on going to the Paddy Field National Park in the sunny city of Sanya in Hainan Province, south China, that you are actually entering Jurassic Park? And why are the green rice fields there not only dotted with tractors followed by swarms of herons but also giant statutes of various kinds of dinosaurs uttering menacing growls from time to time?

Our guide at the park told us that according to stories, the giant reptiles, after ruling the earth for nearly 165 million years, died out at the end of the Cretaceous Period, about 65 million years ago. As they were becoming extinct, a new form of life sprang up—rice. The tiny grain survived the behemoth, proving size is not all.

While rice researchers say this is apocryphal, rice still has an enviably long history with archaeobotanical studies showing it was cultivated in the lower Yangtze River region in China around 10,000 years ago. Since then, the grain has undergone various adaptations for survival and today, is a means of the survival of the human race.

That was one reason for our trip to Sanya since it is one of the testing grounds of the hybrid rice developed by Yuan Longping, famed as the father of the hybrid rice in China.

Every year, Sanya gets an extraordinary flock of migratory birds. They are of the twolegged variety: rice scientists, researchers and agro-technicians who come to develop new varieties and test them in Sanya, which is ideal for cultivation even in winter due to its sunshine.

Yuan, in his 90s, is still involved in the experiments to produce rice with greater yield and pest and drought resilience. Indeed, early in November, he made news once again with a third-generation strain of hybrid rice producing a record harvest by double cropping in Hengnan County, Hunan Province, central China.

A dream comes true

The national park we visited has a tribute to the man who has helped feed millions of people, not only in China but in other parts of the world as well. Near the entrance, there is a structure resembling a giant sheaf of grain. It is a reference to one of Yuans two lifelong dreams in over half a century of involvement in hybrid rice research.

“I dream of resting under big panicles of super hybrid rice—that is, to breed hybrid rice with high and higher yield and stave off hunger from the Chinese,” he said. “The other is hybrid rice covering the whole world—that is, to spread hybrid rice across all rice-growing areas for the welfare of people all over the world.”

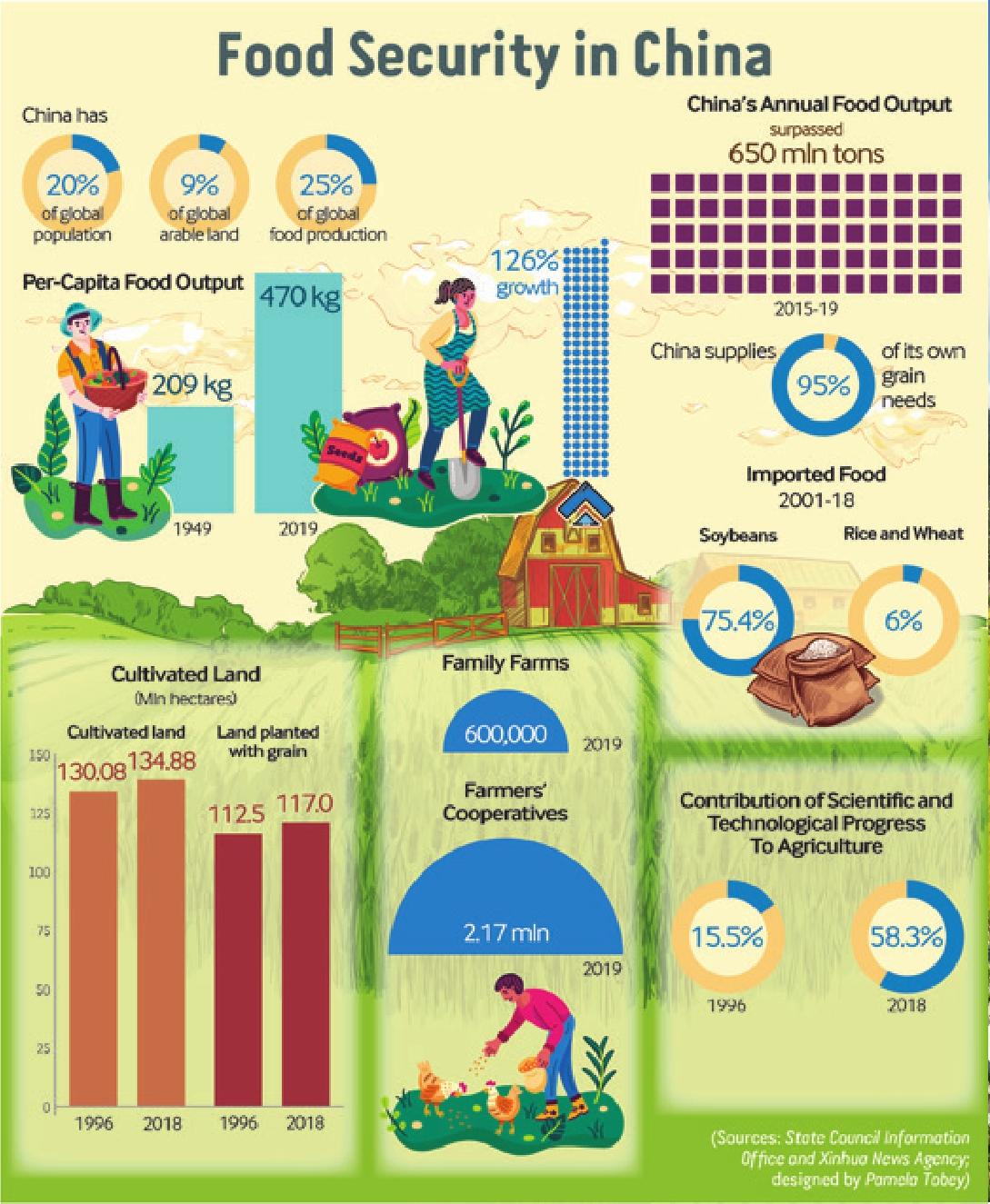

The first part of the dream has been realized several years ago with China becoming self-sufficient in feeding its own population. In 1949, when the Peoples Republic of China was founded, the per-capita food output was 209 kg. In 2019, it had risen to 470 kg, higher than the world average.

Last year, for the fifth consecutive year, Chinas food output surpassed 650 billion kg. Hybrid rice, whose output can be 10-20 percent higher than that of normal rice, has contributed handsomely to the food security. By 2019, it was being grown on 51 percent of harvest areas, producing almost 58 percent of the domestic rice, according to Tu Shengbin, an associate research fellow at the Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

Yuans second dream is also coming true with hundreds of Chinese agricultural experts having been sent to many countries and regions in Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and AsiaPacific to implement cooperation projects in agriculture, improving their self-sufficiency in rice, fruit and vegetable production.

We met Tu in Sanya, where he comes every year to conduct research on hybrid rice. He talked about a proposal by CAS to create a Belt and Road food security corridor to increase the production capacity of countries participating in the Belt and Road Initiative by pooling in their resources.

For example, he said, South Asia and Southeast Asia have abundant natural resources for growing food, from land and water to plentiful sunshine. On the other hand, China has complementary resources such as technical and financial advantages. These could be combined to create a basket of plenty in the region.

“This is the solution to our global food security crisis, the fundamental solution to maintain food security,” he said, while offering us invigorating coffee from Laos brought back from one of their field trips. “Closing the border and restricting exports cannot resolve food security crisis. Only through strengthened cooperation can we solve the problem.”

Harvest of cooperation

Among the examples of ongoing collaboration he gave was the use of a two-line hybrid rice in Viet Nam—planting seeds produced from two lines. The seed was developed in China and grows fast. A heat-resistant hybrid rice that is being grown in Myanmar was also developed in China as well as a third variety that is being cultivated in Arkansas, the United States. Their hybrid rice had made Viet Nam and the U.S. rank among the top rice exporters in the world.Tu related food security to climate change and poverty. The effects of climate change, from storms to droughts, directly impact agriculture and thereby food security and income. Just a few days before our arrival in Sanya, a cyclone was forecast to head for Hainan but then swerved, creating minimum damage. Still, we could see the flattened paddy in the field that it had mowed down, to farmers anguish.

“Hybrid rice is more resistant to many kinds of problems,” Tu said. “It is more resistant to heat, drought and pests. Faced with the problems of global warming, hunger and food security, our solution is to grow hybrid rice.”

Better yield is increasing farmers incomes and expanding means of livelihood. “Hybrid rice seed production bases create jobs for farmers,”Tu said. “Also, hybrid rice can save labor and time, liberating multitudes of farmers from long hours in the fields so that they can engage in other work to increase their income.”

In Guanghan, a city in Sichuan Province, southwest China from where he comes, Tu said the countryside shows signs of that prosperity in its houses. Many farmers have built new houses after their incomes went up by growing hybrid rice.

I had interactions with a group of farmers, including Gao Huangcong, a young man who good-naturedly offered me a ride on his harvester. With the machine he can harvest 1 hectare nearly 50 times faster than manual labor.

However, I realized that though machines have made work easier, its no less strenuous to control them. The harvester looked a bit like a pterodactyl, its serrated front arm resembling giant wicked teeth, mowing down the grain. The machine heaved and baulked in the mud and it needed a great deal of power and control to keep it going. All the while a merciless sun beat down on us, making us sweat hard.

But Gao remained cheerful. Over the deafening roar of the tractor he told me chattily he had bought it with his savings and a micro loan and was his own master. Now his ambition is to start his own company.

The juddering machine stopped from time to time when its maw was full. Then two women waiting nearby brought out large sacks and held them under the long arm, which released the harvested grain. The grain was then poured out onto the road forming a giant yellow ribbon so that it could dry under the sun. The women used a large wooden hoe to spread the grain out evenly. It looked effortless when they did it, so I tried too and the next day, was assailed by aching muscles.

I have returned from Sanya not only wiser about how hybrid rice is promoting food security around the world and Chinas role in it but also about the stellar role of the men and women in the fields who are the unsung heroes of the food security saga. Now I know why they are called the salt of the earth and what working by the sweat of ones brow really means.