Diffuse coronary artery vasospasm in a patient with subarachnoid hemorrhage: A case report

Abstract

Key Words: ST-elevation myocardial infarction; Acute coronary syndrome; Stress induced cardiomyopathy; Coronary artery vasospasm; Cerebral vasospasm; Subarachnoid hemorrhage; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery vasospasm (CAV) is a reversible, transient form of vasoconstriction with clinical manifestations ranging from stable angina to acute coronary syndromes(ACS). Vasospasm of epicardial coronary arteries or associated micro-vasculature can lead to total or subtotal occlusion and has been demonstrated in nearly 50% of patients undergoing angiography for suspected ACS. The mechanism for CAV has been described in literature, but in a subgroup of patients presenting with intracranial hemorrhage, it appears to be multifactorial[1]. These patients tend to have electrocardiographic changes, elevation of cardiac biomarkers of injury and neurogenic stress cardiomyopathy[2].

CAV was initially described by Prinzmetalet al[3]in 1959 as a form of variant angina different from the heterogeneous group of classical anginal syndromes. A complex interplay of mechanisms including increased sympathetic drive to microvascular dysfunction have been described in the literature[4]. Here, we present a case of a patient with an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) complicated by cerebral vasospasm and concomitant severe CAV leading to an acute myocardial infarction presenting as ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) on electrocardiography(ECG). While severe CAV is the underlying pathophysiology for stress induced cardiomyopathy, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and apical scarring are rare in those cases. There are only a few published case reports in the literature with such findings[5-7]. Treatment options are challenging in such cases due to diffuse CAV and intracerebral hemorrhage.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Left sided chest pain.

History of present illness

A 44-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with thunderclap headache. She was found to have a ruptured cerebral aneurysm and SAH requiring neurosurgical intervention. This was followed by severe cerebral vasospasm and neurologic deficits treated with induced hypertension using high doses of vasopressors. Subsequently she was noted to develop chest pain associated with elevated cardiac biomarkers, ST elevation in precordial electrocardiogram leads and new apical hypokinesis evident on echocardiogram. This was promptly evaluated with a coronary angiogram that demonstrated tapering of distal small caliber coronary vessels supplying the territory noted to have wall motion abnormality.

History of past illness

Hypertension that is controlled on atenolol and hydrochlorothiazide outpatient.

Physical examination

The patient’s heart rate was 97 bpm, respiratory rate was 19 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 121/71 mmHg and oxygen saturation on room air was 100%. Cardiac examination revealed a regular rate and rhythm, and no jugular venous distention.Lung exam revealed clear breath sounds without crackles or wheezing.

Laboratory examinations

Cardiac enzymes with the onset of chest pain showed initial Troponin T at 0.60 ng/mL and peaked at 1.72 ng/mL with normal complete blood count and basic metabolic panel.

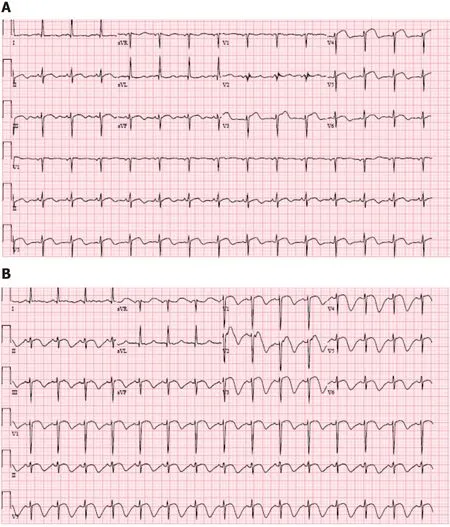

ECG during initial onset of chest pain showed sinus rhythm with ST elevations in V3-V5 (Figure 1A). Repeat ECG in the setting of ongoing symptoms showed normal sinus rhythm with ST elevations in V1-V3 with deep T-wave inversions in the anteriorseptal leads (Figure 1B).

Imaging examinations

Initial echocardiogram during admission was unremarkable with LVEF 60% and normal wall motion. Repeat echocardiogram during STEMI showed a decrease in LVEF to 35%-40% with apical ballooning (Figure 2).

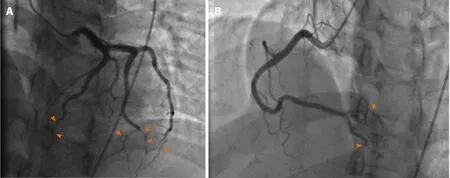

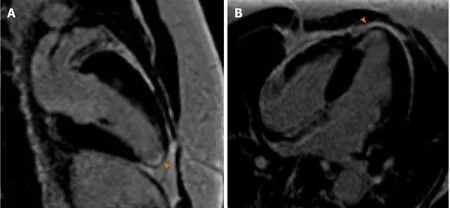

Coronary angiography showed patent left main artery, but 100% occlusion of the mid to distal left anterior descending artery and distal left circumflex (Figure 3A).There was 100% occlusion of the distal posterior descending artery and posterolateral artery (Figure 3B). We were unable to give nitrates during left heart catheterization to see if the vasospasm would improve as patient was hypotensive and we were instructed to keep permissive hypertension by our neurology colleagues. Three weeks after the initial angiogram, Cardiac MRI revealed intense delayed enhancement in subendocardial fashion involving the apical septum and apical segment suggestive of scarred myocardium due to myocardial infarction with LVEF of 58% (Figure 4). We believe this to have been an acute MI as baseline ECG did not show q-waves nor was there a personal history of MI or symptoms indicative of coronary artery disease(CAD) in the past.

Personal and family history

She has a past surgical history of cholecystectomy. She denies alcohol, tobacco, or recreational drug use. Family history is positive for hypertension in her parents.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

ST elevation myocardial infarction secondary to severe coronary artery vasospasm causing reduced left ventricular function and apical ballooning.

TREATMENT

After the coronary angiogram, dual antiplatelet therapy and nitrates were added to her regimen to help reduce CAV. Her discharge medications included aspirin 81 mg daily, carvedilol 3.25 mg BID, atorvastatin 40 mg qhs, clopidogrel 75 mg daily,isosorbide mononitrate 30 mg daily and nitroglycerin sublingual as needed.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Patient follows up regularly with our cardiology clinic. She’s doing well with good exercise tolerance and remains angina free. Her systolic function remains persistently borderline with 50% EF and apical wall motion suggestive of apical infarct three months after her hospital discharge.

Figure1 Electrocardiogram.

Figure2 Echocardiogram on HD 16 showing apical ballooning.

DISCUSSION

We present a rare case of severe CAV leading to apical infarct and low-normal EF in setting of SAH and induced hypertension employed for its treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first case describing the coronary findings in a patient with SAH and apical infarct on CMR.

Figure3 Coronary angiogram.

Figure4 Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging shows delayed gadolinium enhancement suggestive of apical scarring and nonviability.

The typical pathogenesis for myocardial ischemia involves coronary artery atherosclerosis and/or plaque rupture[8]. Our patient had minimal risk factors for CAD and suffered an acute myocardial infarction due to severe CAV which is known to be triggered by high sympathetic drive in patients with SAH. It is believed that excessive sympathetic drive in such cases lead to mismatch in myocardial oxygen demand and supply leading to neurogenic stunned myocardium (NSM)[9,10].

Neurogenic myocardial stunning has been described frequently in medical literature and is described as a state of reversible left ventricular dysfunction that occurs in up to 30% of patients with SAH. Echocardiographic manifestations of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy can be found in 1% to 6% of SAH patients with CAV being one of the underlying mechanisms[10,11]. Overall involvement of myocardium and the incidence and description of SAH complicated by cerebral and coronary vasospasm is seldom described in literature[12]. Animal studies have shown when blood is injected into the subarachnoid space, it is associated with increased amounts of coronary vasospasm in the subjects due to vagal pathway paralysis induced by sympathetic overactivity[13]. This sympathetic overactivity can also occur as a result of rising intracranial pressures from SAH due to increased secretion of cerebrospinal fluid triggered by hemorrhage[14,15]. Elevated catecholamine levels can be linked to cerebral vasospasms and have been associated with left ventricular dysfunction[11]. Therapy for cerebral vasospasm includes hypervolemia and induced hypertension, which may further result in potential cardiopulmonary complications like myocardial ischemia and pulmonary edema[16]. Proposed interventions like mechanical circulatory-assist devices with intra-aortic balloon pump have been shown to be successful for isolated patients with severe myocardial dysfunction complicated by cerebral vasospasms, but has not been studied thoroughly in this patient population[17].

Incidence of CAV in the setting of ACS has been studied with varying percentages of frequency based off populations studied. In a Taiwanese population, patients suspected to have coronary ischemia underwent coronary angiograms with findings of non-obstructive CAD, but ergonovine provocation testing was positive in 41% of patients[18]. In a French study, Caucasian patients being worked up for acute MI showed CAV positive in only 15.5% of patients[19]. Diagnosis and treatment of CAV has been well described in literature, but data in SAH remains scarce. Some research has been attempted in this area, in which prophylactic beta-blockers were hypothesized to reduce catecholaminergic surges in order to reduce the incidence and complications that arise from NSM, but a meta-analysis by Luoet al[20]showed no statistical benefit to this therapy. Clinical evidence is widespread for CAV and treatment modalities using nitrates and calcium-channel blockers; however, in the subset of patients complicated by SAH, there is limited data regarding acute cardioprotective strategies[3].

Our patient was empirically treated with heparin infusion, aspirin therapy and calcium channel blocker (nimodipine) and was not taken to the catheterization lab immediately due to suspicion for coronary vasospasm due to SAH and high doses of vasopressor use. However, in order to attain a definitive cardiac diagnosis, the angiogram was done showing diffuse epicardial CAV resulting in her cardiomyopathy and evidence of myocardial infarction seen on CMR. Her delayed enhancement seen on CMR with wall motion abnormalities was intense and in subendocardial fashion which is indicative of an MI than stress induced cardiomyopathy like Takotsubo,which generally leads to little midmyocardial or patchy delayed enhancement. Due to permissive hypertension requirement from neurology colleagues, her initial management of MI was tricky. Once her symptoms resolved, she was initiated on guidelines directed medical therapy of cardio selective beta-blocker and antiplatelets.Scarcity of medical literature relevant to this specific clinical scenario calls for individualized management approach. As we identify large percentage of patients with SAH and electrocardiographic abnormalities, elevated cardiac biomarkers and wall motion abnormalities, more data on how to carefully proceed with risk stratification, diagnosing and treating acute coronary syndromes in this population is needed[4].

CONCLUSION

Severe diffuse coronary artery vasospasm can lead to myocardial dysfunction and acute myocardial infarction in patients with SAH. Further research is needed to understand coronary vasospasm happening concomitantly with cerebral vasospasm in order to attenuate consequences of severe CAV and develop cardioprotective strategies to minimize end-organ damage.

World Journal of Cardiology2020年9期

World Journal of Cardiology2020年9期

- World Journal of Cardiology的其它文章

- Dispersion of ventricular repolarization: Temporal and spatial

- Clinical significance of prolonged chest pain in vasospastic angina

- Pericardial effusion with tamponade – an uncommon presentation leading to the diagnosis of eosinophilic granulomatosis polyangiitis:A case report