DISASTER WARNING

When Yu the Great tamed the waterways at the heart of China, he was worshiped for ending the misery brought by flooding to those living off the land. Over 4,000 years later, Yu’s memory lives on, but this summer China’s leaders once again faced up to unprecedented floods.

Natural calamities such as flood, earthquakes, fire,and even meteor strikes have wreaked havoc across China for millennia. The battle to prevent damage,mitigate risk, and rescue victims of disasters has gone on just as long.

From ancient irrigation systems in Sichuan to the establishment of China’s first professional national firefighting body to the construction of the mighty Three Gorges Dam, China’s leaders have rarely lacked ambition, and its people rarely lacked courage, when it came to fighting disaster.

But while taming nature was once the catchphrase for modernization, a more ecologically friendly approach is emerging—one that seeks to mitigate the impact of cataclysmic phenomena, rather than try to control the forces of nature.

Now, as locals count the costs of flooding, earthquake victims grieve over trauma, and government devises plans to rebuild, all are left wondering: How do we confront the next disaster?

洪灾的威胁贯穿了中国历史:从大禹治水、修都江堰、黄河多次改道、98年洪灾,到今夏南方的抗洪抢险,中国人民谱写了一部抗洪“进化史”。气候变化又带来新的挑战,与此同时,地震、火灾等灾害的侵袭带来了伤痛,也积累了经验。无论如何,同自然灾害抗争是人类生存发展的永恒课题。

TESTING THE WATERS China’s thousands-year battle for flood control

Ms. Liu surveys what was once a patch of farmland full of sprouting corn, but now resembles a lake.“All the seeds we planted have been submerged…the crops have all been soaked rotten in the fields,” she complains. “It will be very difficult to have a good harvest.”

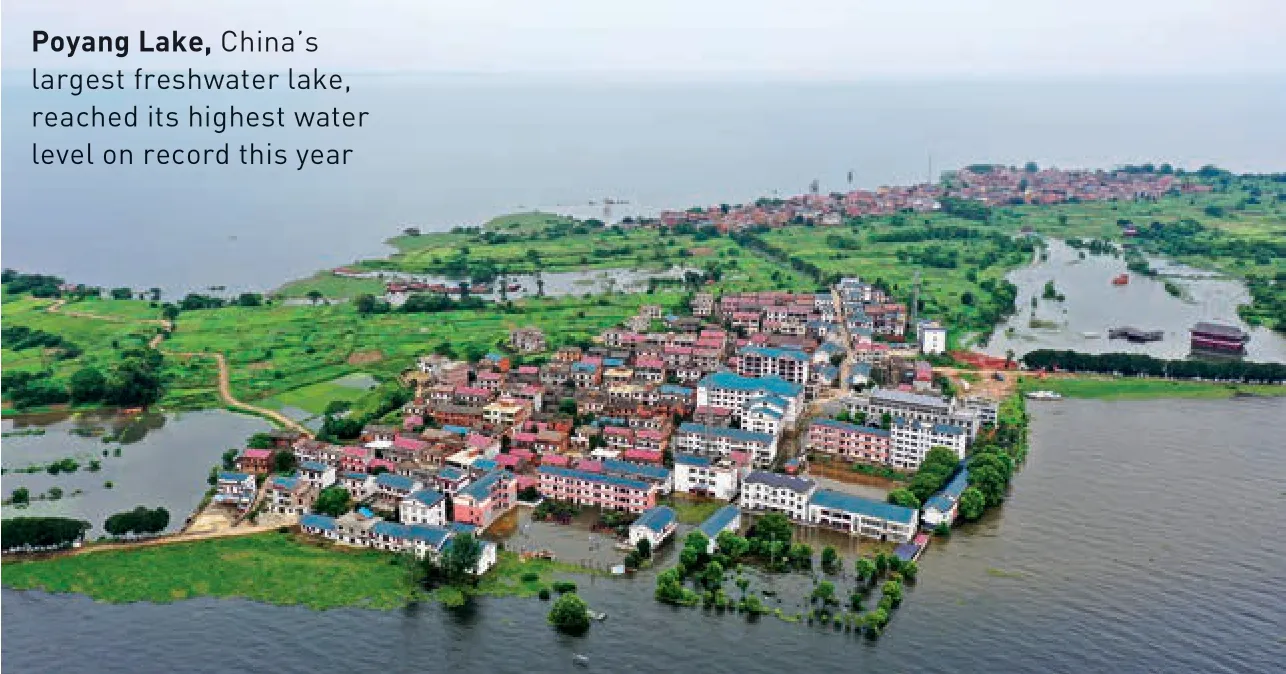

Liu is one of around 60 million people across China who have been affected by abnormally heavy floods this summer. June saw the largest amount of rainfall since 1961 in the Yangtze River Basin, an area home to over 400 million people and 40 percent of China’s GDP. Across the country, 219 people are dead or missing, and over 4 million have been forced to leave their homes.

Floods aren’t uncommon in Liu’s village in Wuwei, Anhui province, but this year there is palpably more fear in the air. “The water level has been rising like crazy,” says Liu, who has been told by local authorities to move what belongings she can to the second floor of her house, then evacuate to a nearby primary school. “The families here have gone to look at the embankment every day. We’re afraid it will break, then the whole village will be submerged.”

Heavy downpours known as the“plum rain” visit China’s southern regions each summer, often breaching the dikes and embankments of the Yangtze River, one of China’s major waterways. This year’s inundations,though, are perhaps the worst since 1998, when over 4,000 were killed across the country. From 1985 to 2018, flooding caused an average 19.2 billion dollars of damage per year in China, and more than 33,000 deaths over roughly the same period. In 1931,140,000 drowned and 2 million died from subsequent famines and disease epidemics after Wuhan was inundated due to severe storms.

Floods have been recorded ever since settlements first emerged along the Yellow River in northern China.Part of the founding myth of Chinese civilization is the story of Yu the Great, a king who united the realm over 4,000 years ago by taming the waterways of China’s heartland.

Successive dynasties have sought to harness the rivers that feed China’s fertile hinterland, but also cause devastating flooding. According to research by Liu Zhenhua at Zhejiang University of Water Resources and Electric Power, between 206 BCE and 1936, there were 1,037 major flood disasters in China, or one every 2.07 years.

Archeological evidence suggests that in the 16th century BCE, the Shang dynasty moved its capital at least once due to catastrophic flooding.Kaifeng, located on the Yellow River and the capital of the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1127), has suffered seven devastating floods since the fourth century, with a new city built on top of the ruins each time.

Floods have even been weaponized:In 1128, Southern Song troops broke levees on the Yellow River in an attempt to slow down the advancing Jurchen army, and in 1938, Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek tried a similar tactic against the invading Japanese,killing hundreds of thousands of civilians and creating millions of refugees.

The Yangtze River has wreaked similar havoc throughout history.Flooding on the river had increased in frequency since the Tang dynasty(618 – 907), when floods were recorded once every 18 years, to once every three years during the 20th century.Though flooding on the Yangtze has only been recorded in detail since 1153, officials noted 54 severe floods in the river’s middle basin during the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368 –1911).

Fighting the floods has been a key occupation of rulers ever since the mythical Yu. The irrigation system at Dujiangyan, Sichuan province, was completed in 251 BCE and has been credited with preventing flooding and ensuring adequate water for farming in the Chengdu Plain ever since.

In 1565, an official named Pan Jixun advocated a system of building embankments to prevent breaches and changes in the Yellow River’s course.Those tactics of building ever more,larger, and stronger dikes, levees, and embankments persisted for centuries.

But the system proved unsustainable.During the late Qing dynasty (1616 –1911), the state paid up to 15 percent of the annual national revenue to protect ever-more valuable land from flooding—a situation that the ailing regime, threatened by internal strife and foreign powers, could not sustain.

The Mao era continued the obsession with large engineering projects. The 1950s saw a frantic campaign to construct dams. In 1952, under Mao’s proclamation “For the great benefit of the people, be victorious in the construction of the flood diversion,”around 300,000 workers completed a flood defense project in Hubei province in just 75 days. They built a series of flood diversion areas and constructed numerous sluice gates to drain water away from densely populated areas.

But these projects were unable to prevent flooding in 1954, and when authorities opened the sluice gates that year, they flooded and devastated thousands of hectares of agricultural land and villages in order to save the cities. In 1975, the Banqiao Dam,completed in 1952 on the Ru River in Henan province, collapsed along with 61 other smaller dams during a typhoon. This released 6 billion cubic meters of water into an area of about 10,000 square kilometres, killing up to 230,000 and sending 40,000 PLA troops into the area for disaster relief.

During these floods, volunteers were sent to repair dikes and to provide flood relief. Over 7,500 workers were sent to bolster the defenses in Wuhan in the summer of 1954.

He Xianhua, a shopkeeper and flood inspection volunteer from Wuwei,remembers working to combat flooding in those times: “In the 70s we went to the Yangtze River to fight the floods.We used poles to carry mud to reinforce the embankment on the river bank. At that time, basically every young person in Wuwei went.”

Today, Mr. He is again tasked with checking water levels and flood defenses in his village. “Sometimes I spend the night [at the flood control station]. You can say I’m on 24-hour duty; at 3 in the morning I get up to check the water level, note it down, and report it.”The floodgate in Wuwei that he is responsible for checking is an“antique,” built in 1954, Mr. He says.In his mind, “the most severe floods were in 1954, 1998, 2016, and this year.”

The 1998 floods were particularly devastating, and marked a watershed moment in China’s approach to flood management. In Jiujiang, Jiangxi province, a dam collapsed apparently because the concrete walls had no reinforcing steel bars inside. When Premier Zhu Rongji visited the dam site, he lambasted local officials through a loudspeaker: “How can you come up with such a shabby, son-of-abitch project? How can you be corrupt to such a degree?”

Corruption and shoddy construction continued to plague flood defense projects. In 2008, Zhang Jianhui, the head of Nanning’s water conservation department, was convicted of taking bribes totalling 26 million RMB over 8 years. In 2011, it emerged that officials in Jingdezhen had spent much of a 300 million RMB flood defence budget on city landscaping instead.

Meanwhile, China’s strategy is changing. “China’s leaders have already realized that China’s flood prevention measures are unfavorable for sustainable development,” says a professor formerly at the Nanjing University School of Geographic and Oceanographic Studies, who wanted to remain anonymous. Future flood management plans should “comply with nature,” she argues.

After the 1998 floods, which cost China nearly 3 percent of its GDP,the government developed a 30-year plan for flood defense that included restoring 14,000 square kilometers of natural wetlands, relocating 2.4 million people away from floodplains, and mass reforestation. The National Climate Change Program has promoted the conversion of farmland back into rivers or lakes, removing some dikes, and dredging rivers where sediment had built up.

These measures tacitly recognized that human activities had contributed to increased flood risks. “Ancient people didn’t have the ability to use massive‘hard’ engineering projects for flood prevention, so they had to think of measures to suit local conditions; these river management measures were more friendly to the environment,” says the professor. “People nowadays can draw lots of lessons from flood prevention measures throughout history.”

The new strategy may be working.Though the Yangtze rose above 1998 levels this year, there have been far fewer casualties. The death rate this year is more than 50 percent lower than the previous five-year average,and the number of houses destroyed 68.4 percent lower, according to the

Ministry of Emergency Management.Still, affected residents worry about rebuilding their lives once the flood water recedes. In Wuwei,“at the moment, [the authorities]haven’t said if there will definitely be compensation,” says Liu, who has lost 4,000 square meters’ worth of crops and numerous chickens.

Furthermore, climate change is likely to increase the risk of flooding in the future. A joint Oxford-Harvard study estimated that economic losses due to flooding in China could rise by 82 percent in the next 20 years.And the number of Chinese living on floodplains is actually increasing,amounting to 453.3 million as of 2015. “As long as you develop flood plains, there will be a risk of flooding.Any flood prevention project,including those that are based on nature, can only reduce the risk; it can’t eliminate it,” says the Nanjing professor.

Moving away may be the only option to guarantee safety, but most are unwilling. “We’ve already lived here for decades,” says Liu. “I’ll think about it if it happens again. But I hope there isn’t a next time.”

– SAM DAVIES; ADDITIONAL REPORTING BY YANG TINGTING (杨婷婷)

AFTERSHOCKS Treating the psychic tremors of the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake

In a quiet corner of the Beichuan Rehabilitation Center for the Disabled, 49-year-old Xiao Zhao sits in a wheelchair with her legs propped up as she embroiders a cartoon panda, her needle seesawing gracefully through a white handkerchief.

“I’ve been having nightmares again about houses collapsing,” she says shaking her head. “Sometimes I have dreams that I can still walk, but when I wake up, I feel even worse. Once I had a dream that not only my legs, but my arms were broken too—I woke up crying.”

On May 12, 2008, a Richter Scale 8.0 earthquake turned entire mountain towns in Sichuan province into rubble,claiming the lives of 69,227 people,injuring 394,643, and leaving 17,923 missing in the ruins. Years afterward,devastated communities struggle not only to rebuild their houses and families, but to recover a sense of worth and hope.

At 2:28 p.m. on May 12, 2008,Xiao was at home caring for her grandmother when the ceiling came down, and her memory cut to black.A neighbor picked her out of the rubble and carried her on his back to an open field, where she waited for medical assistance the whole night as rain began to fall. It would be another week in the overloaded medical system before she received surgery.

In the largest earthquake relief effort in modern Chinese history, Chengdu’s four largest hospitals took in 2,000 casualties, with over 80 percent seriously hurt with broken bones,spinal injuries, or head wounds.More than 5 percent needed an amputation. With 6.5 million homes destroyed, 15 million residents were evacuated from their homes, and 5 million lived in government-built temporary shelters.

In 2009, the province reported that the quake left 7,000 people with physical and mental disabilities. In 2011, an academic study found that 8.8 percent of those from heavily impacted regions showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder(PTSD).

“There was a lot of money flooding in afterward to help disaster-stricken people. But the most difficult challenges to overcome were inside us,” says Xiong Tingyun, who was principal of Leigu Elementary School during the quake when its two buildings collapsed, killing two of his students as well as his own son.

The Sichuan earthquake was the first time China’s burgeoning field of psychology had to respond to a largescale natural disaster.

Three decades prior, in 1976, a Richter scale 7.8 earthquake hit Tangshan, Hebei province, claiming 242,000 lives. There had been no psychological aid during this second deadliest earthquake of the 20th century—psychology departments had been shut down at universities during the Cultural Revolution.

Tangshan psychiatrist Dong Huijian told Beijing News in 2016,“The lack of psychological aid after the earthquake due to the social and medical conditions of the time resulted in too many Tangshan patients with PTSD.”

Dong herself suffered from panic attacks due to loud noises, and had nightmares about her mother who died in the quake. An academic study by Dong, surveying 5,000 people 30 years after the quake, found that 70 percent still suffered negative psychological effects, including PTSD,anxiety, and depression.

Psychology departments were reinstated at China’s universities in 1978, and by the turn of the century,there were 100,000 psychology students across the country.Psychological health was added into the national public health program in 2004. Dong, orphaned at 15 in the Tangshan Earthquake, became the first person in China to receive a PhD in disaster psychology in 2006.

The first instance of organized psychological first aid following a disaster took place after a fire in Xinjiang killed over 300 people in 1994. Local hospitals, overwhelmed with patients with acute stressrelated conditions, appealed to the Ministry of Health for support,who in turn dispatched a team of clinical psychologists from the Peking University Institute of Mental Health.

The team continued to respond to the 2002 Dalian air crash, 2003 SARS epidemic, and 2004 Yunnan typhoon. However, psychological first aid was not well understood by the public, and volunteers were sometimes even regarded with hostility when they showed up at disaster sites, says Ma Hong, a psychiatrist at the Peking University Sixth Hospital.

It wasn’t until the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that psychological aid burst into public conversation, as the emotional distress of the disaster was widely reported in the media. In the first month after the quake, over 1,000 mental health professionals arrived in Sichuan, including psychologists,psychiatrists, and counselors from the army, hospitals, universities, and private clinics.

“Many of the survivors’ faces were wooden; they hadn’t fully realized what had happened yet,” recalled Shi Xiangmei, a 48-year-old psychiatrist at Chengdu’s West China Hospital who volunteered for the disaster relief.One 3-year-old girl from Yingxiu town was discovered by the team after having sat by her mother’s corpse for two days and nights, and had ceased eating and drinking due to emotional distress.

Volunteers patiently coaxed the girl with games, eventually building a relationship of safety and trust that helped her recover over months.But the challenges were many:Older residents of the Qiang, Yi,and Tibetan ethnicities didn’t speak Mandarin, and many were not accustomed to sharing their families’intimate woes with strangers from the city.

“We had to shift our thinking,”noted psychiatrist Deng Hong, lead organizer of West China Hospital’s aid effort. “In the hospital, there are long lines of patients waiting outside of your door. But in the neighborhoods, nobody is looking for you. We needed a new model for how to go in and provide care to a community.”

Psychiatric teams set up counseling offices in schools, and adapted a Hong Kong curriculum for fostering resilience for elementary school students. The counseling office was open for drop-in meetings one day a week, and some children were invited for individual psychotherapy. For three years, they organized a summer camp for orphaned children.

Volunteer counselor Mo Xiaohong held multiple small group sessions,including a Qiang embroidery circle.Singing Qiang songs at times became a shared vessel for grieving. One group was dedicated to bereaved mothers, attended by 46 women who wanted to bear children again.

“We need to combine Western psychiatry with local culture,reaching out to the community in local language and with respect to local customs. Additionally,cultural resources can be a point of connection and emotional healing,”said Deng.

Yet 12 years on, even as many of Principal Xiong’s students have entered college, and parents have welcomed new children into the family, many Sichuan residents still struggle to make sense of the pain.

One Friday night, the father of one of Xiong’s students got drunk,wrapped his wrists in electrical wire, lay down next to his wife, and electrocuted them both.

“Despite our work, we do hear about cases of suicide,” said Mo. “It’s difficult to say who is to blame.”

Nevertheless, the earthquake h

as left the landscape of disaster relief in China permanently changed, as the fledgling discipline’s haphazard beginnings develop into a better integrated and prepared psychological first aid system.

For a generation of Chinese psychologists, psychiatrists,and counselors, Sichuan was a training ground for new modes of psychological aid and new techniques for reaching vulnerable communities.“The world’s experts all came [to Sichuan]. Professors and students had opportunities for training and practice,” says Gao Jinying, a Hong Kong family psychologist who volunteered after the quake.

Many of the same teams formed in Sichuan continued to mobilize for the 2010 Qinghai earthquake, 2010 Gansu mudslide, 2015 Tianjin port explosions, and 2018 knife attack in Shaanxi.

Professionalization and standardization remain ongoing efforts. In May 2018, on the 10th anniversary of the Sichuan earthquake, an international symposium on psychological aid hosted by the Chinese Psychological Society and the Chinese Academy of Sciences outlined the nation’s post-disaster intervention work standards, including guidelines on informed consent and the protection of privacy.

“We had no concept of mental health before the earthquake;only after did we learn about how important it was,” reflected Principal Xiong. Mental health is still a fresh concept, especially in rural areas,and a lack of broader mental health education prevents many from accessing psychological services.

Since the earthquake, China has implemented its first mental health law in 2012, and the first national five-year mental health work plan in 2015, to protect the rights of mental health patients and promote the development of the sector.Frontline volunteers have returned to Chengdu and founded China’s first internationally certified community rehabilitation center to continue serving patients outside the hospital ward.

Xiao puts the finishing touches on the piece of embroidery that has taken her two hours, for which she will receive 8 RMB. She subsists primarily ondibao, or subsistence allowance from the government,and passes her days alone in the rehabilitation center with a daily video call to her newborn grandson back in the village.

“I started embroidering to take my mind off the pain,” Xiao says.“Pillowcases, hats, dresses, flowers,pandas, little birds, butterflies;anything you can draw, I can embroider.”

“Or else my nerves hurt so much I could cry,” she mutters. “There’s nothing to be done: It will be aching every day for the rest of my life.”

– TINA XU (徐盈盈)

BLAZING TRAILS Two years of deadly forest fires in China highlight the importance of professional firefighters

As fires blazed through the mountains in Liangshan in March,turning 270 hectares of forest to ash, 19-year-old Mahai Wuge and his team spent four days and nights fighting the scourge.

With the road out blocked, the firefighters took shifts sleeping on the ground in between battling the flames. By the time the fire in Sichuan province was extinguished ten days later, 2,044 firefighters and volunteers, four helicopters, 142 fire trucks, 64 emergency trucks, and one satellite had been deployed; 18 firefighters and one guide lost their lives in the effort.

“Those who died were right behind us; we went up the mountain together,” Mahai recalls. “It was their first time out. The number one thing you need to look out for is wind direction and terrain. They went where the grasses are high,where in one second the fire can get dozens of meters tall.”

Firefighting in China has only recently begun to professionalize.In 2018, the China Fire and Rescue Team was inaugurated by President Xi Jinping, hiring 18,000 new recruits into the country’s first dedicated national firefighting force.Previously, many firefighters were military personnel transferred to do firefighting temporarily.

Continued calls for reform came after a 2019 fire in Liangshan took the lives of 30 firefighters, two of whom were only 18 years old. While the US has 1.58 firefighters per 1,000 people, China has fewer than 0.2, reported the Beijing News.

“I have always called for putting the safety of personnel first when fighting a forest fire,” wrote Liu Hutang, former head of the Forest Fire Prevention Command in Hainan province, in a since-deleted Weibo post in 2019. He told the South China Morning Post shortly after, “Our country puts economic profits in first place and human lives at the bottom,” referring to the lack of government investment on training and personnel.

Mahai had just graduated from a technical secondary school when he saw the calls to hire civilian firefighters under the local forestry department in 2019. Unable to join the military due to his height, Mahai became inspired to apply for the job by videos posted by firefighters on the streaming app Kuaishou.

As first responders, Mahai’s team lives at the fire station 24 hours a day, seven days a week during the January-to-June dry season.After subtracting living expenses,he is left with 1,800 RMB out of a 2,600 RMB monthly salary. As with much Chinese contract labor, there is no additional health insurance,though Mahai’s colleague had his immediate medical expenses covered by the department for a recent injury.

Given the dangerous conditions,long hours, and low pay, firefighting is a harrowing profession, but Mahai hopes to return next fire season. “I like the feeling of serving my country,” he told TWOC, citing the 20 fires he put out in his first year on the job.

“Professionalism has a lot of benefits. It is a road that must be taken,” Liu wrote. “A tree can regrow after it is burned down, but a person cannot be resurrected after they die.” – T.X.

WHEN STARS ATTACK An ancient disaster from the sky baffles historians

Every day, an estimated 25 million pieces of space debris enter our planet‘s atmosphere. Fortunately,most of these are small, even microscopic, and burn up before they reach the ground.

Scientists calculate, though, that each day an extraterrestrial object at least 40 centimeters in diameter might make it to the Earth’s surface.A meteorite at least ten times that size hits the Earth in any given year,and something even larger comes our way every century or so—as residents of Qingyang county in today’s Gansu province discovered one fateful evening in 1490.

The Veritable Records of the Ming,the official chronicle of the dynasty,noted that “stones fell like rain” in Qingyang county in the spring of 1490.Contemporary local records suggest as many as 10,000 people were killed by the falling rocks. The official history described some rocks as big as a goose egg and others as small as a chestnut, although it doesn’t mention any casualties. Modern researchers have questioned the enormous death toll, but the event certainly spooked the residents of Qingyang, and most of the survivors fled the area to resettle elsewhere.The lack of corroborating data or physical evidence from 1490 makes it difficult to confirm if the cause of the devastation was an impact event from outer space or a freakish phenomenon from Earth.Some scholars have suggested the damage could have been caused by abnormally large and intense hail. But similar incidents from the annals of Chinese history suggest that a meteor might indeed be to blame.

In 616 CE, a “shooting star” may have landed in the camp of the rebel Lu Mingyue. Ten of Lu’s troops were killed when the meteor collapsed a siege tower. Records from Yunnan province in the early 14th century tell of an “iron rain” that destroyed crops and damaged homes across several counties.

Unexplained disturbances from above could be almost as worrying for China’s rulers as it was for people in the affected area. Almost every imperial capital had an observatory,which tracked the movement of heavenly objects in the sky, updated the calendars, and kept an eye out for anything which might be a portent that Heaven was displeased with their emperor’s rule.

Researchers have also compared accounts from Qingyang with more recent—and better documented—impact events. In 1908, a meteorite exploded a few kilometers above the Earth in Eastern Siberia. The Tunguska Blast flattened trees and devastated a fortunately unpopulated area about 40 kilometers in diameter.A 1994 paper by Kevin Yau, Paul Weissman, and Donald Yeomans from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at CalTech suggested that a “somewhat larger stony meteorite exploding over a populated area” might explain reports like the one from Qingyang county in 1490.

Events as massive as the Tunguska Blast or the Qingyang Incident are rare in the annals of history, but they are a sobering reminder of what can happen as the Earth makes its way through a busy solar system.

– JEREMIAH JENNE

——