Gametogenesis and reproductive traits of the cold-seep mussel Gigantidas platifrons in the South China Sea*

ZHONG Zhaoshan , WANG Minxiao , CHEN Hao , ZHENG Ping , LI Chaolun , ,

1 CODR and KLMEES, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China

2 Laboratory for Marine Ecology and Environmental Science, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266071, China

3 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

4 Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China

5 Center for Genomics and Biotechnology, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou 350002, China

Abstract Gigantidas platifrons (Bivalvia, Mytilidae), the dominant species at the Formosa cold seep, relies on methanotrophic symbionts dwelling in its gills for nutrition. The reproductive patterns of G. platifrons provide fundamental information for understanding the population recruitment of this species. However, we know very little about important processes in reproduction, such as gametogenesis and symbiotic bacteria transmission. To this end, we described the developmental patterns of the gonads from nine surveys and juvenile length-distribution from one-year larval traps and detected bacteria in gonad from G. platifrons samples. Our results show that G. platifrons is a functionally dioecious species. The reproduction of G. platifrons is discontinuous, with spawning maturity peak around the fourth quarter of the year. The seasonal reproduction of G. platifrons was further supported by the unimodal shell length distribution of the trapped juvenile mussels. Given the small oocyte size (48.99–70.14 μm), which was comparable to that of coastal mussels, we proposed that G. platifrons developed via a free-living, planktotrophic larval stage before settlement. The blooms at the water surface can also supply the development of the planktonic larvae of G. platifrons. Meanwhile, no bacteria were observed in gonads, suggesting a horizontal symbiont transfer mode in this mussel. Collectively, these results provide fundamental biological information for an improved understanding of the early life history of G. platifrons in the Formosa cold seep.

Keyword: cold seep; gametogenesis; Gigantidas platifrons; reproductive; South China Sea (SCS)

1 INTRODUCTION

Dense communities fueled by autotrophic bacteria are commonly found in deep-sea chemosynthetic ecosystems such as hydrothermal vents, cold seeps, and organic falls (Corliss et al., 1979; Van Dover et al., 2002; Jones et al., 2006; Lorion et al., 2009). The Bathymodiolinae mussel beds are one characteristic habitat in such ecosystems. Reproductive traits are key biotic factors for understanding how the mussels are recruited in these patchily distributed habitats (Laming et al., 2018).

Variations in light and temperature are considered the main abiotic factors shaping the seasonal rhythm of epibenthic species. However, deep-sea ecosystems are generally characterized by having a stable low temperature and no light penetration because of their depth (Lutz and Kennish, 1993). Mussels in shallow water have obvious reproductive cycles closely linked to water temperature cues and changes within a year (Bayne, 1976; Pieters et al., 1980; Newell et al., 1982; Lee, 1988; Borcherding, 1991; Jantz and Neumann, 1998), whereas for deep-sea mussels living more than 500 m below the surface, their reproductive cyclesmay well be different (Kennicutt II et al., 1985; Distel et al., 2000; Miyazaki et al., 2010). Interestingly, most Bathymodiolinae species studied thus far spawn seasonally like the coastal mussels. However, different conclusions of reproductive patterns were drawn, even within the same species Bathymodiolus thermophilus. Berg (1985) and Hessler et al. (1988) suggested the continuous gametogenesis in B. thermophilus based on considerable variations in oocyte size (and reviewed by Tyler and Young, 1999). The hypothesis was rejected by subsequent studies owing to the differences in the relative proportions of the acini and the inter-acinal connective tissue (Le Pennec and Beninger, 1997). The lack of continuous samples taken over a spawning period means these conclusions should be regarded with caution.

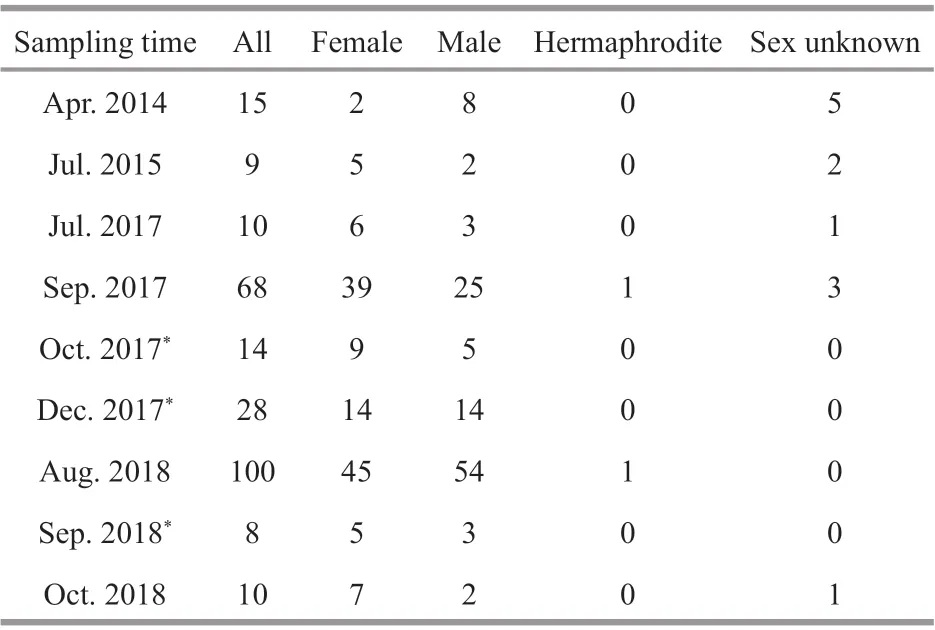

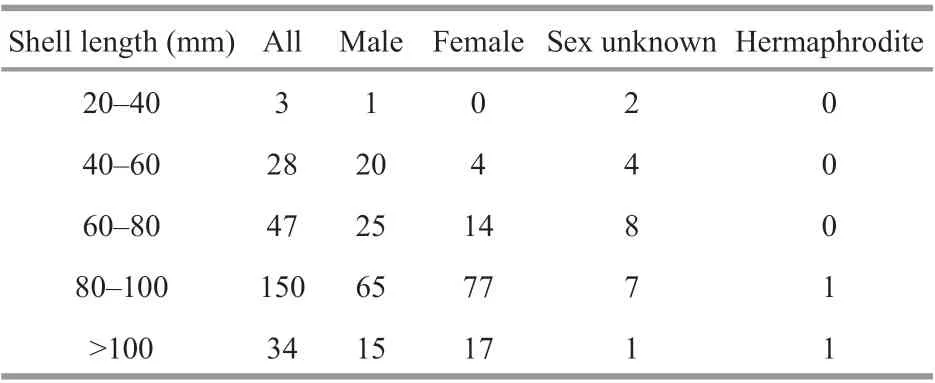

Table 1 Sample information of adult G. platifrons

The genus Bathymodiolus was reclassifi ed into three genera, Bathymodiolus, Gigantidas and ‘ Bathymodiolus like’, according to updated molecular and morphological evidence (Lorion et al., 2013; Thubaut et al., 2013). Gigantidas platifrons (previously referred to Bathymodiolus platifrons) is one of the dominant species in chemosynthesis ecosystems formed by cold seeps and hydrothermal vents in the Northwest Pacifi c Ocean (NWP) (Hashimoto and Okutani, 1994; Xu et al., 2018, 2019). Gigantidas platifrons harbor methanotrophic bacteria in their gill epithelia cells (Takishita et al., 2017), and the bulk of energy (95%) needed for G. platifrons’ nutrition is supplied by these endosymbionts (Wang, 2018). Until now, no direct evidence of the symbionts transfer mode is available for G. platifrons. In some Bathymodiolinae species, it was proved that their symbionts were horizontally transmitted (Fisher et al., 1993; Duperron et al., 2006; Picazo et al., 2019; Sayavedra et al., 2019). Recently, G. platifrons was utilized as a model organism for studying the organismal adaptations to extreme environments (Guo and Li, 2017; Zhang et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2017; Du et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2020), symbiosis (Sun et al., 2017b; Chen et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2019) and adaptive evolution (Sun et al., 2017a) in the deep-sea. However, surprisingly little is known about the reproductive biology of this important mussel species. In our study, we comprehensively analyzed histological sections of gonads and shell-length distribution of juvenile G. platifrons from the northwest Pacifi c to reveal the reproductive pattern of this species, with the aim of understanding the transfer mode of its endosymbionts, and to gain insights into biological features associated with the early life history of G. platifrons.

2 MATERIAL AND METHOD

2.1 Sample collection

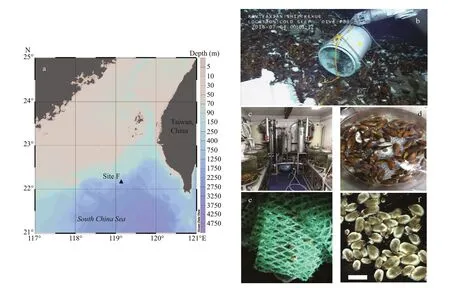

Adult G. platifrons were sampled from the same cold seep location (119°17′08.043″E, 22°06′55.569″N; Fig.1a, site F) in April 2014, July 2015, July and September 2017, and August 2018, by the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Faxian ( Discovery in Chinese) 4500 on R/V Kexue ( Science in Chinese) and October 2018 by the ROV Haixing ( Sea Star in Chinese) 6000 on the vessel Haiyang Shiyou ( Ocean Oil in Chinese) 623 (Table 1). During September 2017 and August 2018, more than 100 mussels in a healthy condition were maintained in an onboard seawater circulating aquaculture system (Fig.1c). They were kept at a constant low temperature (4.3 to 5.1°C) during the incubations and methane was bubbled into the tank twice a day as recommended in Sun et al. (2017b). The maximum methane concentration reached 338 μmol/L at the end of the bubbling period and dropped gradually to 253 μmol/L before the next bubbling period. Meanwhile, the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration dropped to 2.38 mg/L during the methane bubbling and increased to ~7 mg/L again. The lowest DO fall was within the range (1.5–3.5 mg/L) of the DO inside the mussel bed of the Formosa cold seep (Du et al., 2018).

The gonad samples were collected in October and December 2017, and in September 2018, from the mussels in the same circulating aquiculture system with the same culture conditions onboard. The individual shell lengths of each G. platifrons were measured before dissection. After dissecting the individual specimen, the gonad samples of 1–2 mm3were put into 4% paraformaldehyde (Solarbio Inc., Beijing, China) overnight and washed twice with 1× phosphate buffer solution (Solarbio Inc., Beijing, China). The fi xed samples were then stored in 70% alcohol at -20°C, which ensured their preservation.

Fig.1 Samples information

Juvenile G. platifrons were sampled by larval traps (Fig.1b). The larval traps were fi lled with nylon meshes that were proved as the preferred materials for planktonic larvae settlement. The larval traps were settled in the bathymodioline beds of Formosa cold seep during the 2016 COLD SEEP CRUISE, with ROV ‘ Faxian 4500’ equipped on R/V Kexue on 4thof July 2016, and were recovered from the same site 380 d later (19thof July 2017). After the larval traps was recovered on deck, the juvenile mussels were immediately removed from the attached substratum (Fig.1e & f), and fi xed in the fi xative solution described above.

2.2 Histological and FISH analysis

The tissue samples of the mussels were dehydrated via a series of increasing alcohol concentrations (70%, 80%, 95%, and 100%), cleared in xylene and embedded in Paraplast Plus (Sigma, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA). The 7 μm thick sections were stained using Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stains and examined under a Nikon Eclipse Ni-U fluorescence microscope. The seven gonad stages were assigned followed the standards described by Dixon et al. (2006), including a sex-undifferentiated stage, initial gametogenesis stage, early gametogenesis stage, late gametogenesis stage, gamete maturation stage, spawning stage, and post-spawning stage. The gonadal index (GI) for each sample time was calculated according to Seed (1969):

GI=Σ(number of individual in stage x× x)/number of all staged individual,

where x is the numerical value of the stage.

The fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) technique was performed by following Duperron et al. (2006). Briefly, after incubating samples in 1×phosphate buffered solution with tween-20 0.05% (v/v) (PBST, Solarbio Inc., Beijing, China) for 5 min, each slide was hybridized for 1 h at 46°C in a hybridization buffer (0.9 mol/L NaCl, 0.02 mol/L of Tris-HCl, 0.01% SDS, and 20% formamide). The eubacteria probe Eub338 (5′-GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′) with 5′-labeled fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was used to label the endosymbiont. The stained slides were separately examined under a Nikon Eclipse Ni-U fluorescence microscope.

2.3 Shell-length distribution of the juvenile mussel

The shell lengths and shell heights of juvenile G. platifrons were measured through photographs by a stereoscopic microscope (ZEISS SteREO Discovery.V20). The shell length was plotted in 0.5 mm bins to show the shell length frequency histogram.

2.4 Data analysis

The oocyte diameters in each female mussel sample was measured with the Fiji.app (v.2.0.0 National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md, USA). The month was the fi xed factor for one-way ANOVA analyses, and all tests were performed with the GraphPad Prism program (v.7.0.4, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Graphs were drawn in GraphPad Prism v.7.04 and Excel 2016. Data were represented by means±standard errors (SE).

3 RESULT

3.1 Gonad gross morphology

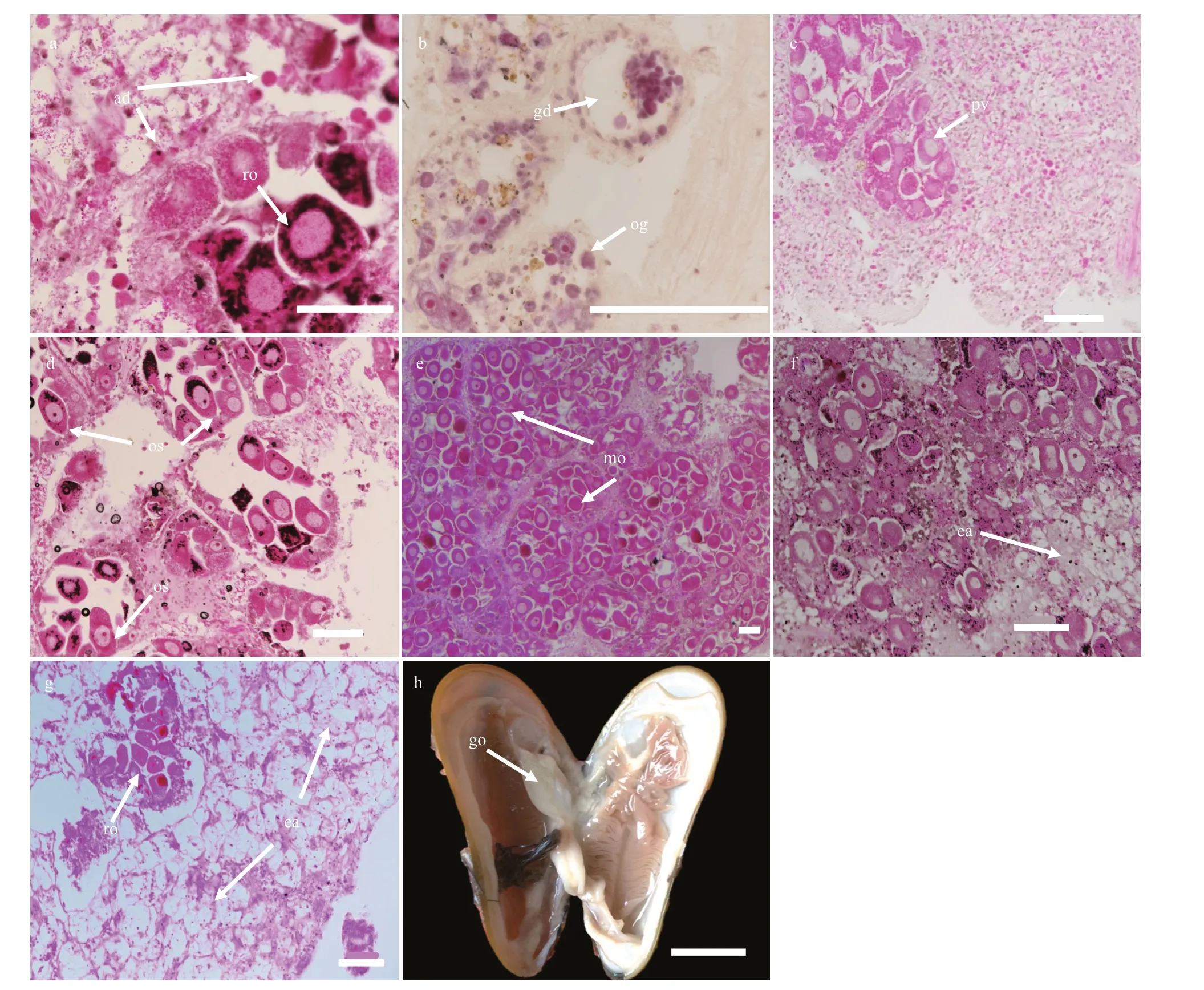

Gigantidas platifrons is a functional dioecious species, although two hermaphrodites were collected (Table 1). The sex of G. platifrons cannot be discriminated by the color of its mantle (Figs.2h & 3h); and can only be determined by microscopy. For male acini, the germinal cells sat within the inner wall of the acini, with spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa developing toward the lumen. The number of acini increased within the mantle in reproductive seasons. For females, we could easily distinguish their oogonia (Fig.2b), previtellogenic oocytes (Fig.2c), and ripe primary oocytes (Fig.2e). The progression of gametogenesis was uniform throughout the gonad and mantle. The gonadal ducts were more apparent in mussels in early gametogenesis. The gonadal duct consisted of fi brous ciliated cells, and these often contained residual oocytes or sperms (Figs.2g & 3g).

3.2 Oogenesis

Before gametogenesis began, only adipogranular cells were present in the ovary and mantle. If individuals had previously undergone a spawning event, the residual oocytes should be present in the deflated acini or gonadal ducts before oogenesis begins. In our study, most of the G. platifrons reproductive tissue was composed of adipogranular cells and most residual oocytes did show signs of degradation, including a grainy appearance, proximity to hemocytes, and absent nuclei (Stage 1; Fig.2a). Oogenesis started in the gonadal part of the visceral mass and extended into the mantle lobes as gametogenesis proceeded. Undifferentiated germ cells on the acinus walls of the female mussels gave rise, through mitotic division, to defi nitive oogonia (10.64±2.42 μm) (Stage 2; Fig.2b). The diameters of oogonia and previtellogenic oocytes were very small and all these cells attached to the acinus walls (Stage 3; Fig.2c). As the oocyte grew and vitellogenesis began, its basal region was capable of extending itself from the acinus wall by means of a broad stalk (Stage 4; Fig.2d). However, as the oocyte developed further and entered late vitellogenesis, the stalk became tenuous and eventually disappeared. These mature oocytes were then detached with the acinus wall and show a free state and their amount of adipogranular tissue was greatly reduced (Stage 5; Fig.2e). Distinct nuclei and nucleoli were evident in ripe oocytes with diameters of about 54.93–86.84 μm (Stage 5; Fig.2e). With more primary oocytes, however, the individual shape of oocytes became polygonal owing to many oocytes crowded in one acinus. During the spawning time, the acini became less dense in the female’s gonad, so the ovum appeared circular or ovoid (Stage 6; Fig.2f). After spawning, hemocytes enzymatically degraded most of the residual oocytes (Stage 7; Fig.2g). Residual gametes may be present in all seven stages, within the acini or gonadal ducts.

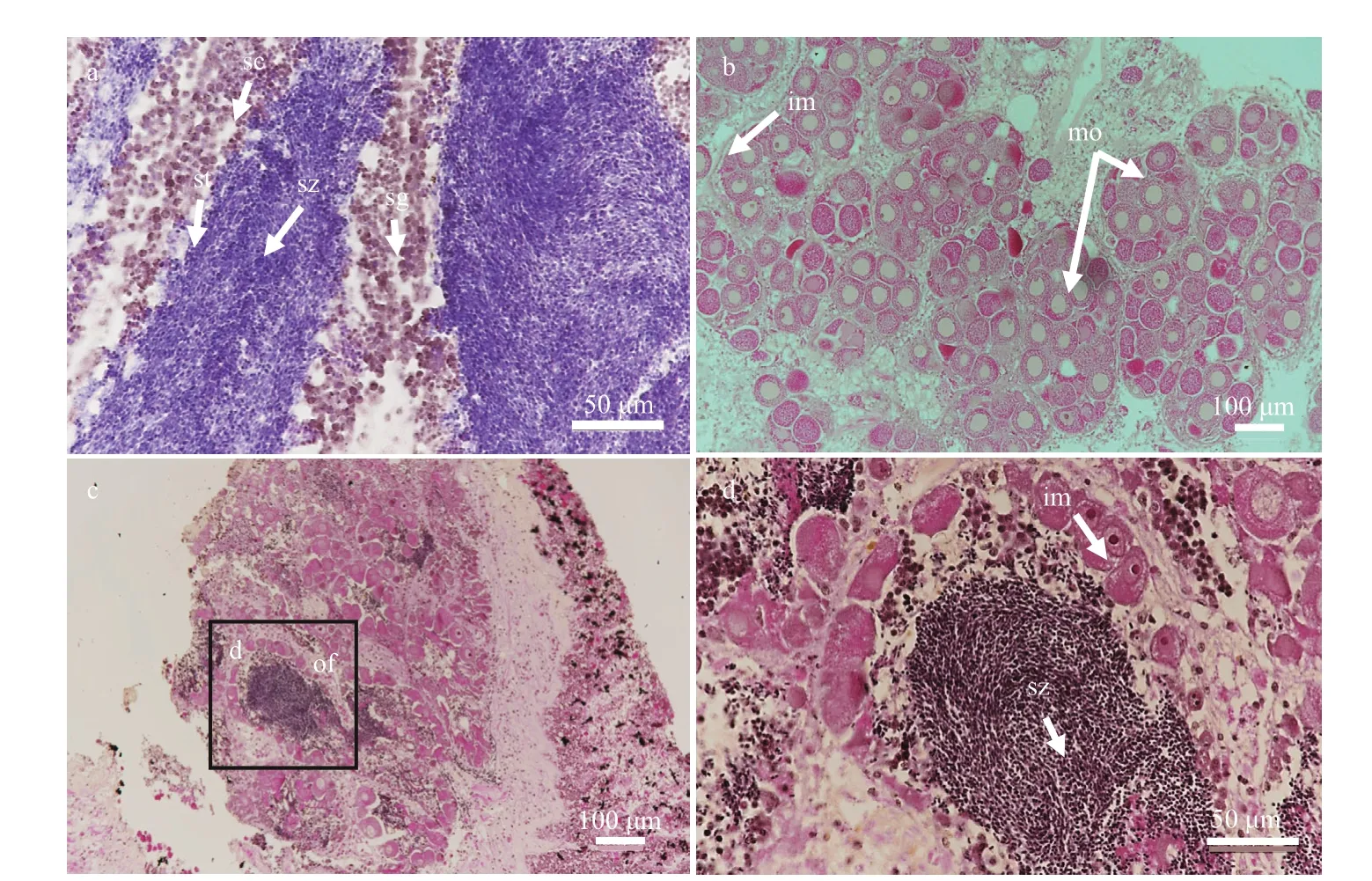

3.3 Spermatogenesis

In G. platifrons males, the general morphology of the testis before gametogenesis resembled that of the ovary. Only adipogranular cells could be found in the male testis and mantle (Stage 1; Fig.3a). If individuals previously underwent a spawning event, residual spermatozoa should be present in their deflated acini or gonadal ducts before spermatogenesis begins. Spermatogenesis started with a proliferation of spermatogonia and spermatocytes near the periphery of the acinus (Stage 2; Fig.3b). Then, some spermatocytes differentiated into spermatids and both spermatocytes and spermatids begin to occupy the lumen of the acinus (Stage 3; Fig.3c). As spermatogenesis proceeded, the spermatids fi lled most of the acinus’ lumen, and the acinus resembled a whorl (Stage 4; Fig.3d). The spermatids differentiated into ripe spermatozoa having a cap-like acrosome atop them, and the gamete density in the acinus greatly increased. Yet the spermatogonia and spermatocytes only form a very thin layer on the periphery of the acinus, for which the amount of adipogranular tissue was greatly reduced (Stage 5; Fig.3e). During spawning, the acini deflate and the spermatozoa density was reduced further (Stage 6; Fig.3f). After spawning was completed, only residual spermatozoa could be found in the acini (Stage 7, Fig.3g).

Fig.2 The process of G. platifrons female gonad oogenesis in stages 1 to 7 (a to g)

3.4 Rare samples display hermaphroditism

Interestingly, two hermaphrodites were observed in the 262 gonadal samples of this study. The cooccurrence/span of both male spermatozoa in the lumen and oocytes in the acini provided solid evidences of occasional hermaphroditism in the deepsea mussel G. platifrons (Fig.4c & d). In both samples, the ovarian follicles were fi lled with ripe spermatozoa and immature oocytes were positioned alongside the stratum basales. In addition, emitted sperm were also observed in these tissue sections.

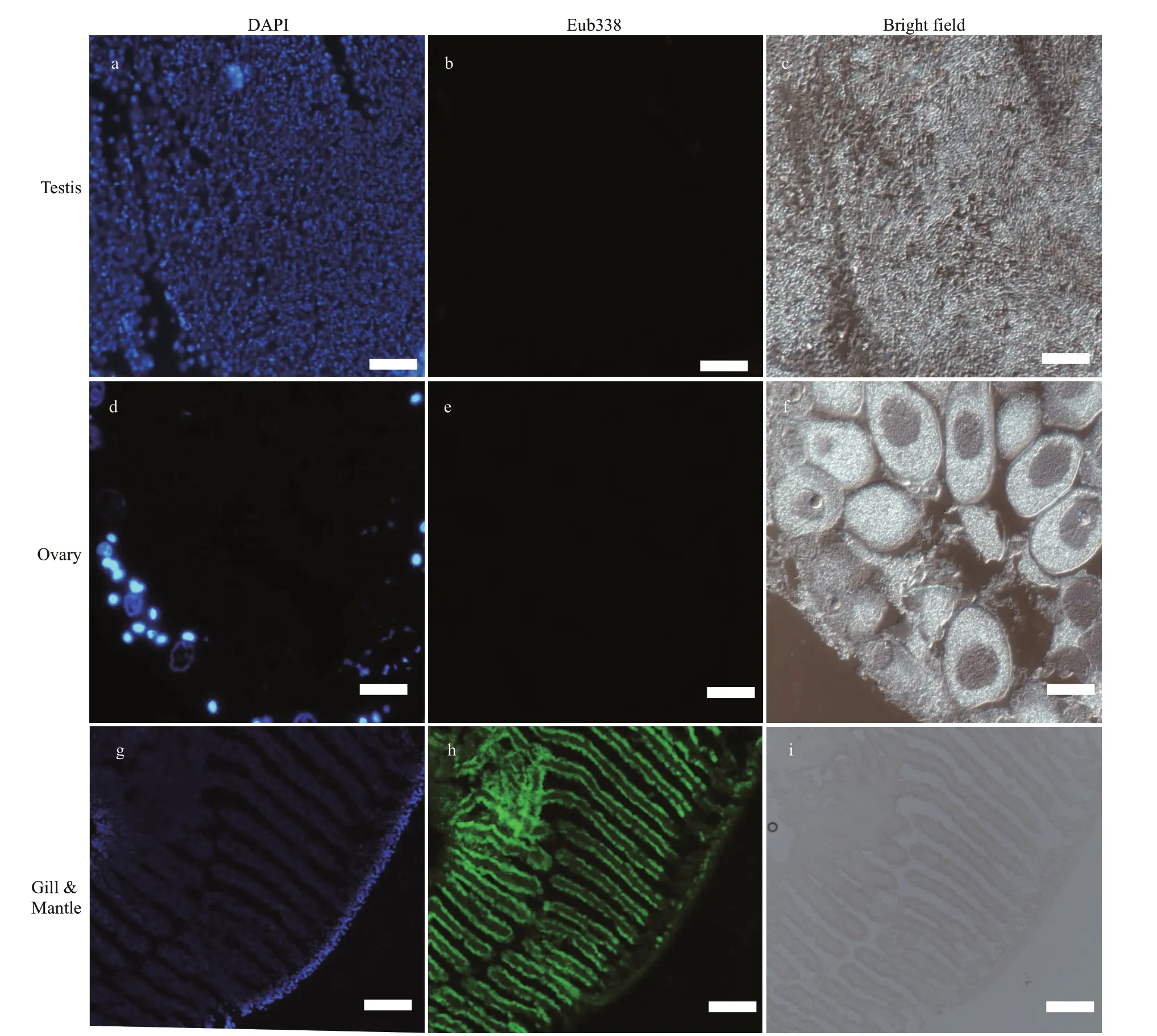

3.5 Symbionts’ mode of transfer

Fig.3 The process of G. platifrons male gonad spermatogenesis in stages 1 to 7 (a to g)

Although an obvious bacteria signal was detected on gill and mantle (Fig.5h), no Eub338 signals were observed in the gonadal sections (Fig.5b & e), supporting that symbiotic bacteria absent in the testis and ovary of the mussel. This result supported the hypothesis that bacteria were not transferred from spawning parents to progeny via the gonads, but rather horizontally through the local aquatic environment.

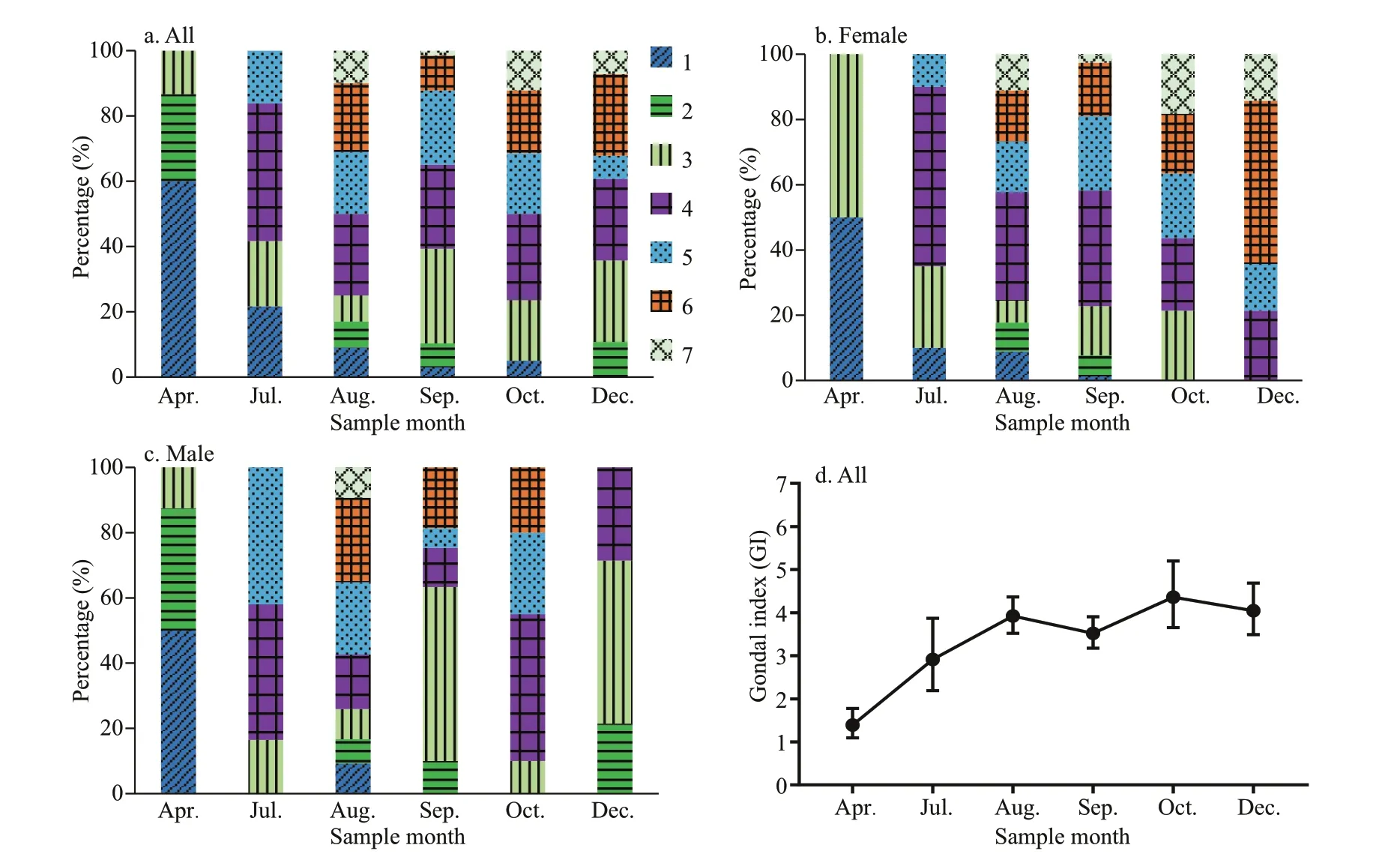

3.6 Periodicity of gametogenesis and spawning

According to the ANOVAs testing, the gonad index was not signifi cantly different among samples from the same months in different years. Thus, we pooled data for the same month, namely July of 2015 and 2017, September of 2017 and 2018, and October of 2017 and 2018. Figure 6a shows the gametogenesis periodicity of G. platifrons inferred from the percentage at each gonad stage. The majority of gonads remained in an early stage until April (Stages 1 to 3) and ripened in late July, when the proportion of Stage 4 gonads increased progressively. Most G. platifrons attained maturity (Stage 5) and spawned (Stage 6 and 7) from August to December. After spawning, most G. platifrons mussels were in Stage 7 or 1, and they were preparing for the next gametogenesis.

Fig.4 Male, female, and hermaphrodite gonadal histology of G. platifrons

The percentage at each gonad stage of female and male G. platifrons are shown in Fig.6b & c, respectively. Their gonadal development was synchronous from August to October; and we found the spawning of the males fi nished earlier than the females as the stage 6 gonads were only available in females in December. Ripe gonads could be observed in female samples from September to December, but they were absent in male samples after October. The GI of all samples pooled together increased from April to December (Fig.6d); the April GI value was signifi cantly lower than the GI of other months ( χ2=42.51, P <0.000 1).

3.7 Sex-ratio patterns and oocyte diameter distribution

The sex distribution among the fi ve shell size categories was compared to test whether the sex ratio was influenced by mussel ages (Table 2). For sex of small individuals less than 40 mm could not be determined except for one male mussel (30.1 mm). More males were observed in samples with a shell length between 40 mm and 60 mm, and the smallest female shell length was 55.7 mm. For those individuals with a shell length above 60 mm, their sex ratio approached 1 (mostly female). The shell lengths of the two hermaphrodite samples exceeded 80 mm.

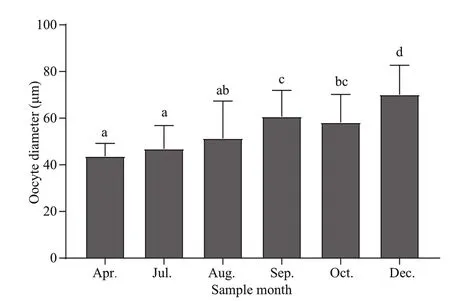

The oocyte diameter (~60 μm) of G. platifrons did not change with shell length. However, this diameter did signifi cantly differ among months. The oocyte diameter in September to December was larger thanthat in April and July (Fig.7). Furthermore, oocyte sizes of G. platifrons maintained in the laboratory were similar to the counterparts immediately dissected onboard the research vessel at sea.

Table 2 Distribution of the sex ratio in G. platifrons mussels in different size categories

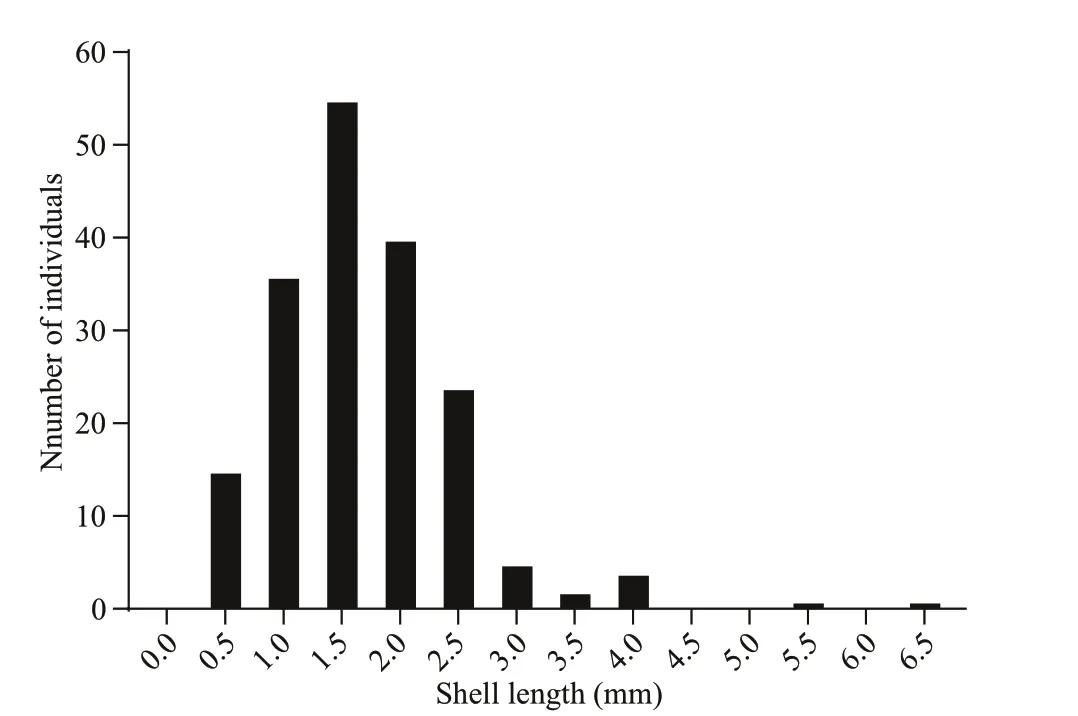

3.8 Shell length-distribution of juvenile mussel

The shell length of the trapped juveniles ranged from 0.48 to 6.45 mm ( n=183). The frequency histograms followed a clear unimodal pattern where the most recruited individuals (155 individuals) fell within 1–2.5 mm (Fig.8). To give a rough estimation of the growth rate, we supposed the longest individual was trapped immediately after the setting of the larval traps. The minimum growth rate of the juvenile was estimated as 0.51 mm/month, which is comparable to other Bathymodiolines, such as G. childressi in Arellano and Young (2009) and I. modiolaeformis in Gaudron et al. (2012). Thus, the settlement of the larvae about 1.96 to 4.90 months before the recovery of the larval traps (from February to May), and the planktonic larval duration was about two to nine months.

Fig.5 FISH analysis of bacteria in G. platifrons testis and ovary

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Gonad anatomy of G. platifrons

The biological sex can be distinguished in littoral mussels by the color of their gonads, with white for males and orange for females. The high concentration of the carotenoid pigment, which is accumulated from the phytoplankton food, makes the ovary orange (Campbell, 1970; Mikhailov et al., 1995). Neritic bivalves can accumulate carotenoids through fi lterfeeding on microalgae. Many of the carotenoids present in bivalves are metabolites of fucoxanthin, diatoxanthin, diadinoxanthin, and alloxanthin, which originate from microalgae (Maoka, 2011). However, methanotrophic endosymbiotic bacteria serve as the food resources in G. platifrons (Wang, 2018). To the best of our knowledge, the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway is incomplete in the methanotrophic bacteria (Schweiggert and Carle, 2016). The limited accumulation of carotenoids may result in the similar color of male and female gonads (Figs.2h & 3h). Gigantidas platifrons is functionally dioecious, given the extremely low (0.76%) percentage of hermaphrodites found in the sampled population. A low-level occurrence of the hermaphrodites is a common phenomenon of Bathymodiolinae mussels (Berg, 1985; Le Pennec and Beninger, 1997; Dixon et al., 2006). The earlier occurrence of males may be the result of their earlier maturity, as recently found for B. septemdierum (Rossi and Tunnicliffe, 2017). However, all Idas species, in which gametogenesis has been studied, are reported as protandric hermaphrodites. Idas modiolaeformis are all males between 2.35 to 3.6 mm, and the sexual transition occurs in mussels between 3.6 to 11.6 mm in length (Laming et al., 2014). Protandrous hermaphroditism is often linked to adaptation to fi nite nutritional resources (Tyler et al., 2009; Ockelmann and Dinesen, 2010; Gaudron et al., 2012; Laming et al., 2014, 2015, 2018). Compared with the organic-falls ecosystems, cold seeps can last much longer (Smith and Amy, 2003; Levin et al., 2016). The reliable and adequate energy supplies in the Formosa cold seep (Feng and Chen, 2015; Niu et al., 2017; Du et al., 2018) could provide enough fi xed carbons for G. platifrons, possibly giving rise to a smaller proportion of hermaphrodites in our study, as suggested by above mentioned fi nite-nutritionhermaphrodite hypothesis.

Fig.6 The percentage at each gonad stage of all samples, female, and male samples, respectively (a–c); GI (mean±SE) of all samples pooled together in different months (d)

Fig.7 Oocyte diameters of G. platifrons (mean±SE) in different months

Fig.8 Shell length-distribution of G. platifrons juveniles trapped through 4 th July 2016 to 19 th July 2017 at the Formosa cold seep

Fig.9 Chlorophyll- a concentrations in the surface water upon the Formosa cold in the South China Sea (SCS)

4.2 Reproductive patterns of deep-sea mussel

Detailed observations of gametogenesis can yield clues for a better understanding of the reproductive patterns of Bathymodiolinae mussels. Considering that breeding was controlled by energy availability, rapid growth, and continuous reproduction would be possible in cold seeps where the continuous food supplies were available (Tyler et al., 2007). However, we found that the GI of G. platifrons signifi cantly differed between April and the second half of the year. As defi ned by Tyler et al. (1982), discontinuous reproduction was observed in G. platifrons as was found in other deep-sea mussels like the B. thermophilus at the 13°N site in the East Pacifi c, B. puteoserpentis and B. azoricus at the Snake Pit site of the mid-Atlantic ridge, B. elongatus from the North Fiji Basin, and G. childressi at the Gulf of Mexico (Le Pennec and Beninger, 1997; Dixon et al., 2006; Tyler et al., 2007). We observed asynchronized development of the male and female gonads in December samples with stage 6 gonads found in the females but absent in the males. Rather than collected from the cold seeps, the gonads in December were collected from the maintained mussels in the circulating aquarium. We observed spermiation during the fi rst few days of aquaculture in September 2017. Mucus-like secreta with swimming sperms alone were observed (Supplementary Fig.S1). Thus, we supposed that the absence of ripe testis (stage 6) in December samples was the result of induced spawning of the males at the beginning of incubation. The periodic variation of GI and oocyte diameters suggested the occurrence of seasonal spawning of G. platifrons as shown in Figs.6d & 7. In April, both a reduced GI and small oocyte diameters indicated an early stage of gametogenesis, suggesting the recent termination of the spawning or a period recovery before gonad development occurred again. The gonads of this deepsea species then developed to maturity, with males and females ready to spawn in the second half of the year as the percentage of ripe germ cells increased or were maintained at high levels from August to December. Thus, a spawning cycle was proposed for the G. platifrons, which was also confi rmed by the unimodal distribution of shell lengths of the trapped juveniles in one year (Fig.8). A similar unimodal shell length distribution of juvenile mussel has been described in deep-sea mussel from cold seeps in the Gulf of Mexico (Arellano and Young, 2009).

It was initially hypothesized that the reproduction rhythm of the deep-sea bivalves is linked to the seepage activity or seasonal temperature variation of surrounding environment (Momma et al., 1995; Philip et al., 2016). However, our long-term in-situ observation indicated that the environments (at least regarding temperature) of the cold seep was stable during our sampling periods (Fig.9 and Supplementary Table S1). In addition, the seepage activity of methane changed over a smaller temporal scale (days or even hours) (Bayrakci et al., 2014; Philip et al., 2016).Thus, other factors should function as signals regulating the spawning rhythm.

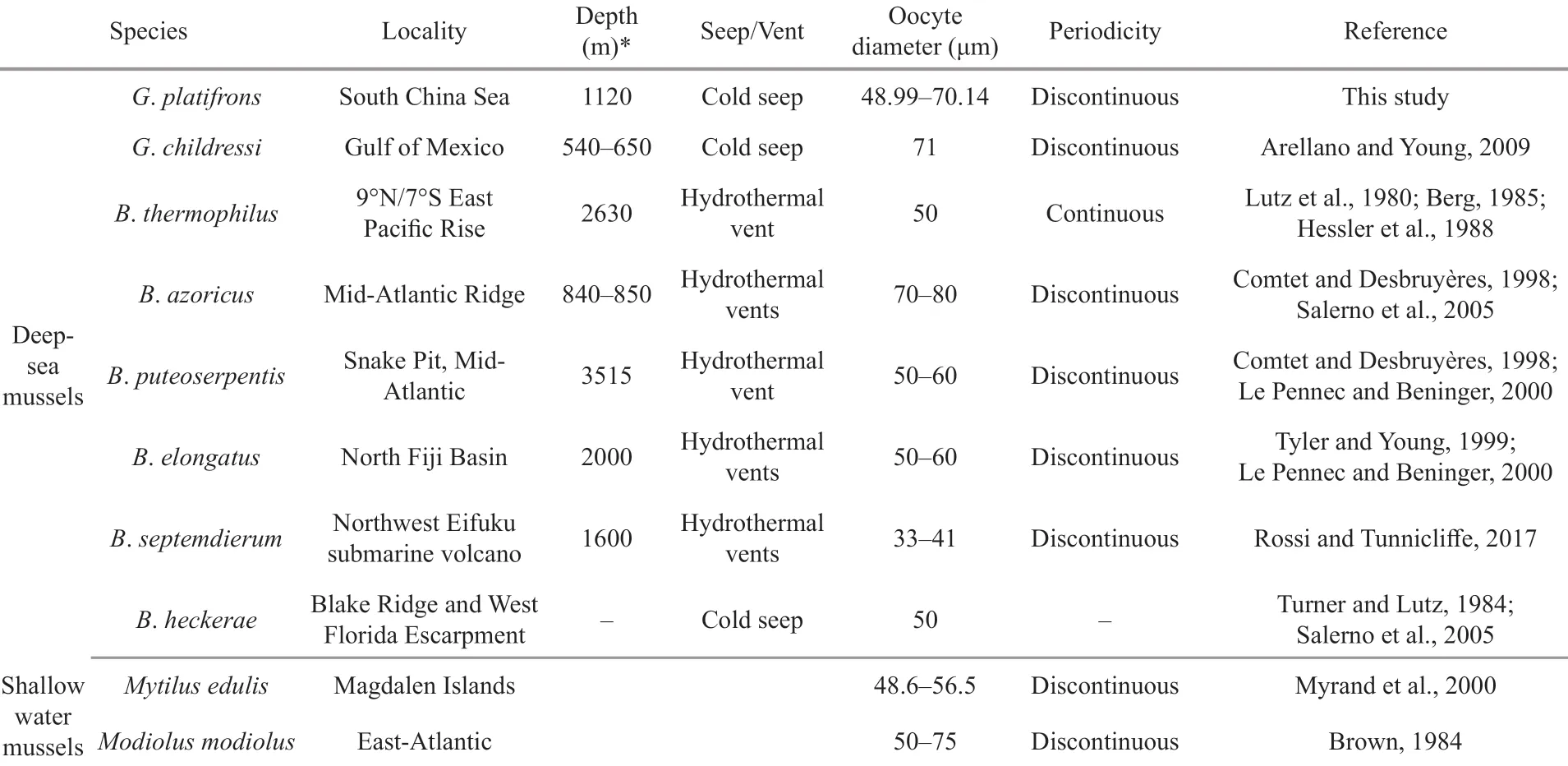

Table 3 Reproductive characteristics of representative Bathymodiolinae species and shallow-water mussels

Another hypothesis is that the spawning of deepsea mussels at sites less than 1 000 m is regulated by seasonal fluctuations in the production of epipelagic organic matter, in which the phytoplankton sink to the bottom (Colaço et al., 2006; Dixon et al., 2006; Tyler et al., 2007). However, in our studied area, the depth is more than 1 000 m and the chlorophyll- a, which is a predictor of photosynthetic primary production, peaked around January (Fig.9, the solid line), two months later than the proposed spawning period of G. platifrons. Thus, our results do not support the hypothesis that the spawning of the G. platifrons is triggered by falling organic matters. As shown in Table 3, similar conclusions have been drawn for other bathymodiolines dwelling at sites deeper than 2 000 m, where the availability of sunken organic material drops to very low levels (Khripounoff and Alberic, 1991; Rossi and Tunnicliffe, 2017).

We observed a time lag of two to nine months between spawning and settlement, supporting the idea that G. platifrons may have a long planktonic period. As observed in other bathymodiolines (Dixon et al., 2006; Arellano et al., 2014), the planktonic larvae of G. platifrons may migrate upwards to fi nd food in the photic zone, which would support the development of the planktonic larvae. Primary production in this region is comprised of ultraplankton (0.2–5 μm) (Jiang et al., 2014) and diatoms (Wang et al., 2018; Ndah et al., 2019), which may supply food for the larvae of mussels (Jørgensen, 1981). G. platifrons spawned before the peak abundance of phytoplankton in the surface water. Similarly, the planktotrophic larvae of B. azoricus settled at a time when the concentration of chlorophyll- a reached its minimum (Colaço et al., 2006), providing enough food for the planktonic larvae. Thus, our results support the hypothesis that the seasonal reproduction of the bathymodiolines may be an ancestral characteristic of mussels, which was mentioned in Eckelbarger and Watling (1995) and in Tyler and Young (1999).

The oocyte diameters measured in G. platifrons fell within the ranges reported for other deep-sea Bathymodiolinae mussel species (i.e., 33 to 80 μm) (Table 3). Due to little oocyte diameter we can infer that G. platifrons larvae should employ the planktotrophic developmental mode (Le Pennec and Beninger, 2000). The larvae of G. childressi have been found in surface waters, and have a planktonic duration that may last up to 13 months and 3 000 km (Arellano and Young, 2009; Arellano et al., 2014). High dispersal and a lack of population differentiation have been found in G. platifrons from all habitats across the NWP (Miyazaki et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2018), supporting the notion of a long planktonic duration of G. platifrons. The long larval duration of deep-sea mussels has been found in many species (Arellano and Young, 2009; Young et al., 2012; Arellano et al., 2014). Furthermore the long planktonic duration is especially important for population recruitment in ephemeral and patchily distributed chemosynthetic ecosystems, and would have led to the wide distribution of G. platifrons.

4.3 Horizontal transmission of endosymbionts

The successful establishment of endosymbionts is the key stepping stone for Bathymodiolinae species to colonize and survive the deep-sea chemosynthetic environments (Barry et al., 2002; Kádár et al., 2005; Laming et al., 2015). We provided evidences for horizontal transmission of endosymbionts in G. platifrons by FISH observation of gonads. According to our results, the gonads of both female and male lacked bacteria (Fig.5). Thus, the vertical transfer hypothesis, where symbionts are acquired through gametes, was not supported for G. platifrons in our study.

A longer planktonic larvae stage up to 13 months has been observed in some deep-sea mussels (Arellano and Young, 2009; Arellano et al., 2014). Limited reductive materials are available in the upper waters where larvae live. Based on the on-board incubation studies, the abundance of the methanotrophic symbiont dropped to a very low level after 34 days (Sun et al., 2017b). Thus, we assume that it was inefficient for maintaining large amounts of symbionts through the planktonic phase of the larvae. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that some seed endosymbiont in a dormant state survived in the planktonic larvae. Nevertheless, based on the microscopy and isotopic results, the symbiotic relationships between the chemosynthetic bacteria and the mussels were found to be established only after attachment (Dubilier et al., 1998; Won et al., 2003; Salerno et al., 2005; Picazo et al., 2019).

During horizontal transmission, the symbionts are re-acquired from the local environment in each new generation. This should enhance the opportunity for increased genetic variation to arise, thereby facilitating adaptation of the mussels to different or changing environments.

5 CONCLUSION

This is the fi rst integrated study to report gametogenesis and reproductive traits of the deep-sea mussel Gigantidas platifrons in the NWP. Gigantidas platifrons is functionally dioecious and develops through a planktonic stage. Our study confi rms that G. platifrons has discontinuous gametogenesis and a seasonal reproductive cycle. Our study also provide evidence to support the hypothesis of horizontal symbiont transmission in G. platifrons. This study of gametogenesis and the reproductive cycle will be helpful to elucidate the population structure and population recruitment strategies of G. platifrons in the NWP. Further studies should address the problems of planktonic larval capture, the long-term in-situ observation of reproduction and recruitment activities, and the artifi cial breeding of this species to make it model species for deep-sea adaptation studies.

6 DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the fi ndings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank all the crews on R/V Kexue, R/V Haiyang Shiyou 623, ROV Faxian 4500, and ROV Haixing 6000 for their assistance in sample collection and all the laboratory members for continuous technical advice and helpful discussions.

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology2020年4期

Journal of Oceanology and Limnology2020年4期

- Journal of Oceanology and Limnology的其它文章

- Review on observational studies of western tropical Pacifi c Ocean circulation and climate*

- Research progress of TiO 2 photocathodic protection to metals in marine environment*

- Smart anticorrosion coating based on stimuli-responsive micro/nanocontainer: a review*

- Status of genetic studies and breeding of Saccharina japonica in China*

- To be the best in marine sciences*

- A review of progress in coupled ocean-atmosphere model developments for ENSO studies in China*