Endometrioma surgery and possibilities of early disease control

Vasilios Tanos, Elsie Sowah

1University of Nicosia Medical School, Nicosia 2408, Cyprus.

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Aretaieo Hospital, Strovolos, Nicosia 2024, Cyprus.

3St. George’s, University of London, London, SW17 ORE United Kingdom

Abstract Aim: The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of surgical management in ovarian endometrioma for early disease control and long-term fertility preservation in adolescents and women of very young age. A history of cyclic pains in adolescents is highly associated with endometriosis. Sonography enables the diagnosis of small endometriomas 1-2 cm in diameter. Although it is obvious that the risk of damage to normal ovarian tissue is diminished when operating and removing a 2 cm endometrioma, it is not approved since there are currently no tools available to identify at-risk patients. Additionally, performing laparoscopic surgery with 5 mm instruments in patients with small endometriomas will likely cause more harm than benefit.

Methods: A literature review was performed using key words for endometrioma surgery, in vitro fertilization(IVF), implantation rate, pregnancy rate and adolescents. The pros and cons of surgical removal prior to assisted reproductive therapy (ART), outcomes of endometrioma surgical treatment before IVF, and current recommendations for endometrioma removal were investigated.

Results: The total patient population from articles supporting removal of endometrioma before assisted reproductive therapy and evidence against were 30,741 and 9983 respectively. However, the only study reporting a statistically significant result found an 8.2% implantation rate for the surgical removal group vs. 12% in the direct-to-IVF group, and 14.9% pregnancy rate in the surgical removal group vs. 24.9% in the direct-to-IVF group. Damage to ovarian reserve and function due to surgery is exacerbated by large cyst size, stripping of the

Keywords: Endometriosis, endometrioma, assisted reproductive therapy, in vitro fertilization, surgery, adolescents

INTRODUCTION

Endometriomas affect 17%-44% of women with endometriosis[1]. Approximately 17% of women suffering from infertility are diagnosed with an endometrioma[2]. The pathogenesis of endometrioma is characterized by sequential and progressive damage of healthy ovarian tissue. During menses, the implantation of regurgitated endometrial cells on the ovarian surface (via tubal lumen) causes a series of biochemical reactions including persistent inflammation, bleeding (at the implantation site) and invagination of the ovarian cortex, adhesions, cystic formations, tissue alterations and deformity[3]. Invagination of the ovarian cortex secondary to metaplasia of celomic epithelium in the context of cortical inclusion cysts has also been proposed as a possible mechanism of endometrioma formation[4]. Hence, the endometrioma pseudocapsule itself is ovarian epithelium containing follicular structures and oocytes. Upon opening the endometrioma after irrigation, endoscopic imaging reveals pinkish tissue that is the ovarian epithelium. The ovarian tissue that is identifiable during endoscopic imaging is thus embedded with endometriotic cells that can continue to proliferate and migrate even, if not destroyed[5].

In addition, ovarian endometriosis, is a marker of more significant pelvic and intestinal endometriotic lesions[6]. Despite the fact that the diagnosis of an endometrioma can be done by transvaginal ultrasound examination at a very early stage, the identification of patients who will deteriorate through development of larger endometriomas remains a major challenge.

Although cyclic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, bleeding, dysuria and/or infertility are the common presentations,symptoms do not indicate the extent and/or progression of the disease. Endometriosis awareness among general practitioners and the public is still very poor. Misdiagnosis and under-treatment occur not infrequently. As a result, endometriomas are often diagnosed when the cyst is very large, and/or the disease has reached an advanced stage - this is especially the case among adolescent women[7]. Hence, many infertility patients present with endometrioma and tubal factor problems with an indication for in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment.

A systematic review of the literature was performed to identify the course of action in treating endometriomas prior to IVF. In addition, 9 current guidelines by international gynecological societies were used as a tool to guide identification of the current gaps in research and evidence for clinical practice. Research was also focused on the pros and cons, as well as outcomes of surgical treatment for endometrioma before IVF. Based on the evidence and conclusions of our research, an algorithm for the management options in endometrioma prior to IVF is proposed.

METHODS

Materials

A literature review of internet/online databases and formal papers and presentations was performed.Internet-based resources included the following: (1) search engines: Google and Google Scholar; (2)research databases: PubMed and Ovid Embase; (3) library database: St. George’s University of London Hunter Database. Numerous scientific journals both print- and web-based were accessed through these databases. Main titles included: Fertility & Sterility, American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology & Reproductive Biology, Reproductive BioMedicine Online, Human Reproduction, and PlosOne.

Methods

Core search terms were: “ovarian endometrioma”, “endometrioma + surgery”, “endometrioma + surgery+ IVF”, “endometrioma + Assisted Reproductive Therapy (ART)”. Additional search terms were: “ovarian endometrioma + adolescent”, “ovarian endometrioma + surgery”, “ovarian endometrioma + adolescent+ surgery” and “ovarian endometrioma + adolescent + IVF + surgery”. PubMed was used as the primary source of literature due to highest yield of relevant material.

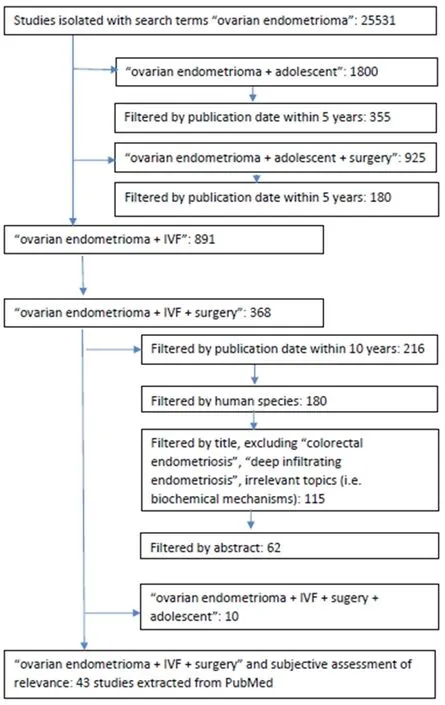

Initial results were further fi ltered by publication date within 10 years. For the “ovarian endometrioma +adolescent” search, the fi lter was limited to 5 years as this is a more specific and contemporary research area, with the aim of amassing only the most relevant and current literature. From the fi nal 180 articles,titles and publication dates were used to further distinguish relevant literature and isolate prospective studies. Additional filters were applied to focus on adolescents. Figure 1 outlines the database search process carried out.

A total of 33 articles matching our search criteria were analyzed and categorized into pro/con of endometrioma surgery prior to IVF depending on the evidence presented.

Fourteen articles provided evidence in support of surgical removal of endometriomas prior to ART. There were two retrospective case-control studies, two retrospective cohort studies and one retrospective analysis.Additionally, there was one committee opinion, one scientific impact paper, one pooled analysis, one literature review, one systematic review and two meta-analyses. Notably there were only two prospective studies - a prospective cohort study and a prospective randomized study [Table 1].

Nineteen articles provided evidence against removal. There were seven retrospective studies and six prospective studies. Additionally, there were two meta-analyses, two literature reviews, one systematic review and one scientific impact paper [Table 2].

Five articles provided evidence for both pros and cons of removal of endometrioma prior to IVF, with a combined total patient population of 6088[8-12]. In seven studies, the research design, number of patients and characteristics, and results extraction were not clear and thus, excluded from our calculations.

For analysis of current evidence on implantation and pregnancy rates between surgical removal of endometrioma and no surgery prior to IVF, only four studies matched the selection criteria. The following exclusion criteria were applied to the search: (1) sample population: women with endometrioma;intervention group: women having surgical treatment prior to IVF; and control group: women with unremoved endometrioma going into IVF; (2) primary outcomes: implantation rate and pregnancy rate; (3)interventional studies (no review papers); and (4) publication date within last 10 years. An exception was made to the fourth criteria in order to include Wong et al.[13]and Garcia-Velasco et al.[14]. The publication date criteria resulted in many relevant studies being excluded. Among the four studies selected, two were retrospective case-control studies[14,15]and the other two were retrospective cohort studies[13,16].Results for the additional investigation into adolescent endometrioma revealed nine relevant articles.Among these articles, three of these were international guidelines, three were review articles, two were retrospective cohort studies, and one was a retrospective case-control study.

Figure 1. Methodology used to isolate relevant articles on endometrioma surgery prior to IVF and endometrioma surgery in adolescents.IVF: in vitro fertilization

Table 1. Pros of surgical removal of endometriomas before ART

Table 2. Cons of surgical removal of endometriomas before ART

RESULTS

Pros and cons of surgical removal of endometrioma prior to IVF

The total population across both pro/con, including control and study patients was 40,724.

Pros of surgical removal of endometrioma prior to IVF

The total patient population of articles supporting removal of endometrioma before ART was 30,741. Table 1 summarizes the “pros” of surgical removal of endometrioma prior to IVF according to current evidence.

Three articles provided evidence that removal of endometriomas reduces the risk of abscess and infection.The risk of endometrioma rupture with or without pelvic abscess development is supported by fi ve studies within the systematic review carried out by Somiglianaet al.[17]. The American Society of Reproductive Medicine committee opinion[18]reports that this rupture may result in abscesses, infection and further progression of endometriosis as well as contamination of the ovary or peritoneum with endometrioma content. Contamination of follicular fluid via accidental aspiration of endometrioma contents, which occurred in 19/314 total patients (6.1%), resulted in lower adjusted clinical pregnancy (0.63; 95%CI: 0.49-0.87,P= 0.005) and live birth RRs (0.60; 95%CI: 0.51-0.86,P =0.003) amongst the exposed and control groups respectively[19].

Ten articles, with a combined total patient population of 7313, provided evidence that removal of endometriomas prior to IVF may improve IVF outcomes as measured by the increase in follicular production, oocyte retrieval, fertilization, implantation, and pregnancy rates, and reduced cycle cancellation rates. Three studies found that the removal of large endometriomas improves IVF outcomes[15,20,21]. One study found that, among patients with unilateral endometriomas measuring > 5 cm, the differences in IVF outcomes between the ovary with endometrioma and the healthy ovary were as follows: (1) less follicles produced in the ovary with endometriomavs.healthy ovary (total number of follicles: 2.6 +/- 1.3 and 4.8 +/- 2.0, respectively;P< 0.0001); (2) less total number of retrieved oocytes (2.0 +/- 1.2 and 4.2 +/- 1.7 respectively;P≤ 0.01); and (3) less number of oocytes retrieved which were suitable for fertilization (0.5+/- 1.1 and 3.3 +/- 1.5 respectively;P≤ 0.01)[20]. Four studies, including a combined total of 6895 patients,demonstrated a lower mean oocyte retrieval during IVF/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) in women with endometriomas compared to normal [Standardized Mean Difference = -0.23 (95%CI: -0.37 to-0.10)[10], (6.6 ± 3.74vs.10.4 ± 5.25;P< 0.001)[12], (5.7 ± 3.1vs.10.4 ± 4.4;P< 0.05)[11], (Mean Difference =-1.50; 95%CI: -2.84 to -0.15, P = 0.03)[22]]. Among 64 total patients undergoing IVF, comparing 32 cases of endometrioma and 32 tubal-associated cases, there was a higher cycle cancellation rate amongst patients with endometrioma (18.3% and 1.7%, respectively;P< 0.05)[11]. One study compared IVF outcomes in 85 patients with endometriomas measuring 10-50 mmvs.83 patients with simple ovarian cysts measuring 10-35 mm, found lower implantation rates in women with endometriomas compared to the cyst group(13.9 and 16.4, respectively;P= 0.03)[9]. A randomized control study of 99 patients with endometriomas,randomized to ovarian endometrioma cystectomy pre-ICSI or no surgery, found no statistically significant difference in fertilization (86% and 88%, respectively), implantation (16.5% and 18.5%, respectively) and pregnancy rates (34% and 38%, respectively) between pre-ICSI surgery and control groups[23].

Two articles, with a combined patient population of 23,114, provided evidence that the removal of endometriomas can also help in the diagnosis of malignancy at an early stage. The lifetime probability of developing ovarian cancer increases from 1% to 2% in the presence of endometriomas[8]. In their pooled analysis of case-control studies, covering a total patient population of 23,114, Pearceet al.[24]found that endometriosis is associated with increased risk for clear-cell (OR: 3.05;P< 0.0001), low-grade serous (OR:2.11;P< 0.0001) and endometrioid invasive (OR: 2.04;P< 0.0001) ovarian cancers.

Cons of surgical removal of endometriomas

The total patient population of articles providing evidence against the benefit of endometrioma surgery before ART was 9983.Table 2 summarizes the “cons” of surgical removal of endometriomas prior to IVF according to current evidence.

Evidence that surgical removal of endometriomas damages ovarian reserve and function - reduced ovarian reserve, increased gonadotropin stimulation, lower embryo transfer, implantation and pregnancy rates, increased risk of cycle cancellation - was provided by 16 articles, with a total patient population of 9603. Eight studies provided evidence that surgical removal of endometriomas negatively affects ovarian reserve. These eight studies included a mix of retrospective[15,25], prospective[26,27], meta-analysis/systematic review[10,28,29]and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists scientific impact paper[8]. Among 1642 women with infertility across three age groups (< 30, 31-35, < 36), there was a lower anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) in patients with previous endometrioma cystectomy (1.23 +/- 0.15) as compared to patients with endometriomas > 3 cm (2.22 +/- 0.23) and patients with non-endometrioma causes of infertility (3.08 +/- 0.1) (P< 0.0001)[25]. In the retrospective case-control of 428 women undergoing IVF, of which 142 hadin situendometrioma at the time of IVF, 112 had laparoscopic endometrioma cystectomy pre-IVF and 174 women had tubal infertility, there were higher cycle cancellation rates in the cystectomy group (7.5% in endometriomain situ, 9.8% in surgery, 2.9% in tubal factor;P< 0.02)[15]. Among 237 patients who were treated for endometriomas via cystectomy, there was a statistically significant decrease in AMH after surgery (mean difference: -1.13 ng/mL; 95%CI: -0.37 to -1.88)[28]. Another study of 193 patients with endometriomas undergoing laparoscopic cystectomy showed that the surgical removal of endometrioma results in reduced ovarian reserve (pre-operative AMH was 3.86 +/- 3.58; average post-operative AMH by 9 months was 1.83 +/- 2.06;P< 0.001)[30].

Two studies, with a combined total patient population of 385 women with endometriomas showed that excision may remove healthy ovarian tissue. According to a histological analysis of endometrioma tissue from 59 patients, endometriotic tissue can cover up to 98% of the entire cyst wall (median of 60%) and reach up to 2 mm in depth[31]. Furthermore, proportionally more endometrioma cystectomies disclosed ovarian stromavs.dermoid cystectomies (80.3% and 17.2%, respectively;P< 0.001)[32]. Since their study found higher implantation (28% and 19%, respectively;P= 0.02) and embryo transfer rates (79.7% and 70.7%, respectively;P= 0.03) in women with simple cystsvs.endometrioma, Kumbaket al.[9]proposed that poorer IVF outcomes due to the presence of endometriotic cysts during IVF may be attributable to the disease itself, rather than the cystic mass. Higher doses of gonadotrophin may be required for ovarian stimulation in patients with endometriomas surgically removed pre-IVFvs.patients with intact endometriomas[8]. This is supported by data from the RCT of 99 patients with endometriomas, which found that those who had endometriomas surgically removed pre-IVF required more days of stimulation (14.0+/- 2.5,P< 0.001) as compared with those who went directly to IVF (10.8 +/- 2.6,P< 0.001)[23]. A recent retrospective study investigated ART outcomes in endometriomasvs.other types of endometriosis and found that previous endometrioma removal surgery was independently associated with lower pregnancy rates with ART multivariate analysis OR: 0.39 (0.18-0.89;P= 0.16)[33].

Limited benefit of surgery - based on ovarian responsiveness, oocyte quality and endometrial receptivity -was reported by four articles with a combined total patient population of 375. A recent prospective study of women with unilateral endometriomas found no difference in: (1) ovarian responsiveness (3.7 +/- 2.4 and 4.1 +/- 1.7;P= 0.54), (2) number of suitable oocytes (3.1 +/- 2.6 and 3.5 +/- 2.3;P= 0.51), (3) number of ‘high quality’ embryos (1.8 +/- 2.1 and 1.8 +/- 1.4;P= 0.00) and (4) fertilization rate (64% and 64%,P= 0.96) between the affectedvs.intact ovary, respectively[34]. Additionally, one literature review concluded that despite often lower numbers of oocytes retrieved, oocyte quality remains the same after surgery[35].Finally, one prospective cohort study of 103 patients proposed that endometrial receptivity and accessibility is similar both in the presence of endometriomas and without. When comparing normal and affected ovaries in patients with unilateral endometriomas, there is no statistical significance in the difference in fertilization rates (72.4% and 69.6%,P= 0.644)[12].

Surgical removal of endometriomas to improve fertility in the adolescent population

The few international guidelines which explicitly address treatment of adolescent ovarian endometriomas unanimously present a stepwise treatment plan commencing with medical treatment first, followed by surgical management, and fi nally combination treatment when necessary. The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology 2016 guidelines state that laparoscopy may be indicated in adolescents with chronic pelvic pain who do not respond to medical treatment[36]. Similarly, in their 2018 statement on adolescent endometrioma, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend conservative surgical treatment, followed by 6 months of GnRH as adjunct treatment if surgical management was inadequate[37]. In 2019, the Endometriosis Treatment Italian Club also recommended that laparoscopic surgical treatment of endometriomas in adolescents with moderate-severe dysmenorrhea should not be carried out until medical treatment with estrogen-progestins or progestins has been attempted[38].

Regarding the specific techniques and decision-making for surgical removal of endometriomas in this population, transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy (TVHL) has been recommended in adolescent patients with ovarian endometriomas measuring < 3 cm[39]. More recently in 2018, Benagianoet al.[40]suggested TVHL for endometriotic cysts measuring < 20 mm and laparoscopic surgical removal of endometriotic cysts measuring > 20 mm in the context of disease that is refractive to medical treatment.

There are very few studies addressing the specific topic of surgical removal of endometriomas for fertility preservation in adolescents. Statistically significant fi ndings from Cocciaet al.[16]retrospective cohort study inclusive of women of all reproductive age with endometriomas who underwent IVF/ICSI showed an 8.2%implantation rate for the surgical removal groupvs.12% in the direct-to-IVF group, and 14.9% pregnancy rate in the surgical removal groupvs.24.9% in the direct-to-IVF group. Additional studies not limited to the adolescent population revealed that older age was found to be associated with lower AMH for both cystectomy and control groups[25]. Moreover, amongst women who had endometriomas removed surgically pre-IVF, higher pregnancy rates were found among women aged < 35 (34.3%) as compared to women aged> 35 (25.9%)[41]. One study described an 11-year-old patient with endometrioma who presented initially with amenorrhea and had spontaneous menarche post-surgical removal[42].

DISCUSSION

Size and type of endometrioma can influence appropriateness of surgical management

Studies have shown that bilateral endometriomas and those larger than 7 cm are associated with more damage to ovarian reserve due to surgery, as compared to those that are unilateral and smaller than 7 cm[43].Regarding laparoscopic surgical removal, damage to ovarian tissue may be proportionally related to the size of the endometrioma: excision of cysts measuring > 4 cm results in more significant damage[44]. Recently,Cocciaet al.[16]reported that size is perhaps the most significant factor with regard to ovarian retrieval:for each mm increase in size, there is a decline in predicted number of oocytes retrieved. Bilateral ovarian endometrioma removal presents a worse outcome as compared to unilateral endometriomas: the decline in ovarian reserve, independent of age and destruction of the ovarian parenchyma, still predicts a worse outcomevs.unilateral and no surgery[16]. On the other hand, Ashrafiet al.[12]found in their prospective cohort study that clinical outcomes - such as fertilization, maturation rate and total formed embryos - were no different between unilateral endometriomas and no endometrioma. This is consistent with fi ndings by Yuet al.[45]that there were no significant associations found among laterality of endometrioma, ovarian reserve, and pregnancy outcomes of IVF/ICSI for women with infertility having undergone laparoscopic cystectomy.

Ovarian reserves

Most studies employ the stripping technique to treat endometriomas in order to reduce recurrence, at the expense of significant damage to healthy ovarian tissue. One retrospective cross-sectional study found that AMH was not reduced in patients with endometriomas independently, but that it was reduced in patients with previous endometrioma removal surgery[46]. However, another study showed that among young women (aged 18-22) there were statistically significant lower median AMH levels even prior to surgery in those with bilateral endometriomas as compared to controls and those with unilateral endometriomas[47].In a recent prospective case-control study which compared women without endometriomas, women with endometriomas, and women who had surgical removal of endometriomas, it was found that damage to ovarian reserve increased respectively across all three groups[27]. This presents the possibility that ovarian reserve damage may be proportional to the extent and frequency of surgery, again, with all employing the stripping technique. In many of these studies, it is suggested therefore to assess ovarian reserve before undertaking surgical removal of endometriomas, and that this factor may be significant enough to recommend against surgical removal. Proper preoperative evaluation, and adequate training and experience of the laparoscopist, are crucial parameters that determine the long-term success of the endoscopic approach[48,49].

Surgery as a means of preserving ovarian tissue

Surgical removal of endometriomas can enable cryopreservation of ovarian tissue. During surgical removal of endometriomas, healthy fragments of ovarian cortex can be isolated and subsequently cryopreserved,reportedly a highly effective technique for fertility preservation[50]. Furthermore, Carrillo et al.[50]recommended that ovarian tissue preservation through cryotherapy be individualized based on factors that overlap with those we have identified as priorities for the surgical management of endometrioma: patient’s age, ovarian reserve status, presence of bilateral lesions, and repeated surgery. In the adolescent population,ovarian tissue and/or oocyte cryopreservation is especially important to optimize future fertility as suggested by Benagiano et al.[40].

Since endometriomas progressively damage ovarian reserves, it seems logical that the surgical treatment of an endometrioma of a smaller size, preferably lower than 3 cm, would preserve healthy ovarian tissue.The problem is we lack the scientific knowledge to identify those patients that will rapidly deteriorate and develop larger lesions. Gynaecologists who perform TVHL can operate on small endometriomas less than 3 cm with precision and safety using 5Fr instruments[51].

Adolescent population

Adolescents and very young women with endometriomas present a very high risk of premature ovarian failure and infertility. Endometriomas in adolescents may have a different pathophysiological origin[40]as well as different manifestation from that of adult endometriosis. The diagnosis of endometriosis in adolescents is often delayed. This delay is attributable to several factors including a puzzling clinical picture such as the presence of both cyclic and acyclic pain[52], lower proportion of incidental findings(23%) as compared to adults[53], or lesions which are difficult to identify laparoscopically due to clear color and benign appearances[37]. Yet, up to 80% of adolescents with chronic pelvic pain refractory to medical treatment end up with a diagnosis of endometriosis[54]. Currently, the diagnostic pathway involves presence of relevant symptoms (i.e., chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea), response/no response to medical treatment,and finally diagnostic laparoscopy[37]. Once endometrioma is diagnosed, treatment follows guidelines mentioned previously - surgery is indicated if refractive to medical treatment. There are currently no original studies investigating the early detection and subsequent surgical removal of endometriomas in the adolescent population as it relates to the patients’ fertility goals. Much of the existing body of research focuses on older adults because these are the women presenting with concerns for fertility or are actively seeking IVF; however, as endometriosis may often be present but lying dormant and undiagnosed throughout adolescence, there is a major opportunity for early diagnosis and treatment at the very initial stages when focis of 2-3 mm in diameter of endometriosis appear on the ovarian surface, accompanied by neoangiogenesis and chronic inf l ammation promoting adhesions, ovarian dysfunction and infertility.

The main concern with regard to endometrioma surgery for adolescents is the high risk of future recurrence. A retrospective cohort study showed that long-term recurrence of endometriosis is higher amongst younger women as compared to older women[55]. Larger cyst size and younger age were reportedly associated with recurrence in a 2014 retrospective study comparing recurrence rates across subgroups of 550 women with endometriomas[56]. In their 2017 study of adolescents with endometrioma who had undergone laparoscopic cyst removal via enucleation, Lee et al.[57]found that 16.2% experienced recurrence after fi rst-line surgery, and that recurrence rates increased proportionally to time since surgery. An attempt to strip the pseudocapsule to reduce the risk of recurrence will lead to the destruction of a high volume of healthy ovarian tissue with inadvertent high AMH results and infertility.

Proposal for individualization of management by case identification

Based on the literature, the clinical assessment of endometriomas requires endoscopic establishment of the diagnosis. High-risk adolescents, in addition to older women seeking fertility treatment, can benefit from early diagnosis of endometrioma. It is therefore essential that early identification of eligible patients is improved and standardized, through stepwise clinical reasoning and diagnostic testing as presented in Figure 2.

Modern ultrasound scanning machines enable accurate diagnosis of endometriomas as small as 1.0 cm,depending on the knowledge of the operator and BMI of the patient[58,59]. In addition to diagnosing endometriomas, the myometrial and the sub-endometrial areas should be meticulously examined, as adenomyosis and adenomyotic cysts may be found; when endometriomas measuring < 3 cm are identified,we should proceed with TVHL. Bigger endometriomas can progress straight to IVF or be treated with laparoscopic surgery. Figure 2 outlines options regarding endometrioma management.

Performing standard laparoscopic surgery using 5 mm bipolar instruments on small endometriomas < 5 cm minimizes the probability of preserving healthy ovarian tissue. Instead, smaller sized endometriomas enable an “easier” operation to be performed that results in less damage to healthy ovarian tissue, such as, surgery with 5F bipolar ball or Argon/Plasma jet laser[51]. This also ref l ects the change to transvaginal surgery as a preferable technique over standard laparoscopy in the case of small endometriomas prior to IVF[51]. Experts in reproductive surgery increasingly support the ablation method using bipolar techniques, avoiding excessive coagulation and carbonization effect[60]. Carrillo et al.[50]summarized various factors inf l uencing post-surgery ovarian reserve, one of which was the competence of the surgeon as measured by the ability of the surgeon to minimize removal of healthy tissue, identify the extent of endometriotic infiltration and the borders of the lesion, and the ability to minimize coagulation during the procedure. The different treatment options of endometriomas in adolescents and very young women, according to their clinical characteristics are presented in Figure 2.

Recently, Roman et al.[61]proposed using plasma energy ablation as an alternative to cystectomy, fi nding fi rst in their pilot study of eight women that this technique may spare 90% of healthy ovarian parenchyma that would otherwise be removed during cystectomy. In a subsequent study (30 women with unilateral endometrioma and no previous surgery), they found a statistically significant reduction in ovarian volume and antral follicle count (AFC) (P < 0.001) among women who were operated by cystectomy as compared to those operated on by plasma energy ablation. This association was independent of age, previous pregnancy, and endometrioma size[62].

Figure 2. Treatment options for adolescents with endometriomas according to their clinical characteristics. TVU: transvaginal ultrasound; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; US: ultrasound; OC: oral contraceptive; LNG-IUD: levonorgestrel intrauterine device

Limitations of review

There are important limitations in both the quality and quantity of the available evidence. The lack of randomized control trials (RCTs) investigating surgical management of endometriomas and IVF significantly impacts the quality of evidence. This lack of RCTs results in (1) the inability to have internationally consistent guidelines and (2) a high level of inconsistency and contradiction in the pros and cons analysis of results. Overall, despite endometriosis and endometrioma being two relatively high yield research areas, endometriomas in IVF is a contemporary issue, which is ref l ected in limited existing data;available data often refer to endometriosis as whole, which resulted in their exclusion from our analysis,and among studies specific to endometriomas there are very limited material evaluating surgical treatment in the context of IVF. This is evidenced by the minimal number of recent studies matching our search criteria on the surgical removal of endometriomasvs.non-surgical as pre-IVF treatments (four studies). In addition to these limitations, which affect the yield for adolescent-focused endometrioma research, there is a dearth of studies on the effect on long-term fertility following surgical removal of ovarian endometriomas in adolescents. Despite making exceptions to the exclusion criteria to include more studies, the analysis was extremely limited.There are specific limitations of the literature to acknowledge. The articles cited in the pros and cons analysis in which there was insufficient information on study size and patient characteristics may have provided biased or skewed data based on unknown factors relating to population characteristics. Regarding the diagnosis of malignancy following surgical removal of endometriomas, for which two articles were cited in Table 1, the majority of available data is limited to theoretical deduction or speculation, rather than statistically significant conclusions due to lack of (prospective studies or RCTs) studies investigating this specific association.

Conclusive remarks

Surgery for endometriosis/endometriomas has a strong potential to increase fertility and optimize ART outcomes under certain circumstances. Surgical outcomes depend significantly on the patient’s age, size of endometrioma, interest in fertility preservation, and on the surgeon’s skill and experience. Adolescents with endometriomas, considered a high-risk patient population due to delayed diagnosis and vulnerable fertility,stand to benefit from surgical removal not only as it is currently indicated for treatment but also, for longterm fertility preservation. Endometriosis is a very aggressive disease that severely compromises the quality of life and fertility of women, and TVHL can provide an early diagnosis for the treatment of high-risk patients.

Minimal invasive surgery of endometriomas offers safe and effective management. Several reports have demonstrated that recurrent operations of endometriomas, operating on bilateral endometriomas and big endometriomas > 7 cm are associated with diminished pregnancy rates. This evidence must guide the laparoscopic gynaecologist in his/her adjustment and modification of surgical protocols and especially, the timing of operation. Furthermore, endometrioma removal via plasma energy ablation is a relatively new but promising method with regard to both symptom and fertility improvement. A 2019 retrospective study of 21 women showed decrease in post-operative dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia and chronic pelvic pain as compared to preoperative baseline, as well as a 46.2% post-operative pregnancy rate[63]. While promising,currently there are no clear guidelines regarding ablation as research remains limited due to the lack of robust studies directly comparing ablation to other minimally invasive techniques.

Ultimately, the absence of randomized controlled studies as well as the significant damage to ovarian reserve resulting from the endometriosis disease process itself result in a topic that has garnered significant controversy over the years. An individualized approach to decision making on the surgical removal of endometriomas that is focused on early detection and optimization of ovarian reserve, as well as having a well-trained laparoscopic surgeon, are all essential for guiding management and improving fertility outcomes.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the study.

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and interpretation, construction of the fi gures: Tanos V

Performed data acquisition, major writing of the manuscript, as well as provided administrative, technical,and material support: Sowah E

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the fi ndings can be found in several publications as described in Materials and methods section of the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conf l icts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2020.

- Mini-invasive Surgery的其它文章

- Current state of minimally invasive treatment of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer

- Early experience of uniportal video assisted thoracoscopic surgery in a New Thoracic Unit in Hospital Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- Robotic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis

- Transcatheter mitral valve implantation: different fi xation techniques

- Quality of life, pain, and functional respiratory recovery after lobectomy for early stage non-small cell lung cancer: a review of the literature comparing minimal invasive and open procedures

- Transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: state of the art