Chronic airspace disease:Review of the causes and key computed tomography findings

Kianoush Ansari-Gilani,Hamid Chalian,Negin Rassouli,Arash Bedayat,Kevin Kalisz

Kianoush Ansari-Gilani,Negin Rassouli,Department of Radiology,University Hospitals,Cleveland Medical Center,Cleveland,OH 44106,United States

Hamid Chalian,Department of Radiology,Duke University Medical Center,Durham,NC 27705,United States

Arash Bedayat,Department of Radiological Sciences,University of California-Los Angeles,Los Angeles,CA 90095,United States

Kevin Kalisz,Department of Radiology,Northwestern University,Chicago,IL 60611,United States

Abstract

Key words:Chronic; Airspace disease; Computed tomography; Imaging; Radiology;Disease

INTRODUCTION

Filling of the alveoli with material that attenuates X-ray beams more than the surrounding parenchyma causes airspace opacification.This is equivalent to the pathological term consolidation[1].Ground glass opacification (GGO) or consolidative opacification of the lungs can be caused by different materials,including water,pus,blood,cells,protein,and fat.There is no definite definition of chronic airspace disease,however.An opacity that persists in follow-up studies and does not resolve in the expected time and after appropriate treatment can be called chronic.Chronic airspace opacification,while persistent,may show minor or major changes in distribution and appearance[2].

The list of causes of chronic airspace disease is long and exhaustive.The goal of this study was to review the causes of chronic airspace disease and discuss the clinical,laboratory and radiological findings that can help radiologists and clinicians to narrow down the differential diagnosis.

DEFINITION OF AIRSPACE DISEASE

As stated above,airspace opacification is caused by filling of the alveoli with material that attenuates X-rays more than the surrounding parenchyma[1].Airspace opacity can be seen as GGO when the bronchial and vascular markings are still visible,or can manifest as consolidation opacification,usually with air-bronchogram,when the bronchial or vascular markings are obscured[3].Also stated above,airspace opacity can be caused by different materials,including water,pus,blood,cells,protein and fat.Chronic airspace opacities may persist throughout multiple imaging studies over time,with minimal or no significant change.It bears repeating from above that,alternatively,while persistent,they may show minor or major changes in distribution and appearance[2].

Causes of chronic airspace disease can be divided into four general groups,namely inflammatory,infectious,neoplastic,and miscellaneous.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

As stated in the Introduction,given the overlapping presentation and appearances of many of the causes of chronic airspace disease,clinical and laboratory information,together with imaging findings,are crucial to narrow down the differential diagnosis.

Clinical information and patient background

A patient's past medical history can provide clues to the etiology of chronic airspace disease.For example,history of asthma can suggest eosinophilic pneumonia or eosinophilic granulomatosis,with polyangiitis as cause of the airspace disease.A history of sarcoidosis is suggestive of alveolar sarcoidosis.Malignancy risk factors,such as smoking history,may suggest pulmonary adenocarcinoma.Immunocompromised state may raise concern for pulmonary tuberculosis or posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD).History of collagen vascular disease may raise concern for pulmonary hemorrhage and organizing pneumonia (OP).Multiorgan involvement may suggest collagen vascular disease or PTLD.History of treatment with anticancer medication should raise the concern for pneumonitis,which may have imaging patterns of different chronic airspace disease (Tables 1-4).

Laboratory findings

Reviewing the patient's laboratory values can help the radiologist to narrow down the differentials for chronic airspace disease.For example,presence of eosinophilia suggests eosinophilic pneumonia,while presence of neutropenia will be more suggestive of atypical/fungal infection,such as angio-invasive aspergillosis.Elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (commonly known as ACE) suggest sarcoidosis.Positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (commonly referred to as ANCA) can be seen in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Tables 1-4).

Imaging findings

The imaging findings and imaging signs can also be very helpful in narrowing down the differential diagnosis (Tables 1-5).For example,the presence of specific imaging signs,such as halo sign or reverse halo sign,can be seen in OP or angio-invasive aspergillosis.Pseudocavitation and fissural retraction can suggest the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma.Distribution of the opacity,whether involving the upper (sarcoid) or lower (lipoid pneumonia) lung,can also be helpful.In addition,the appearance of opacification,which can be either GGO (adenocarcinoma,hemorrhage),consolidation(lymphoma) or mixed (OP,angio-invasive aspergillosis,adenocarcinoma),can provide helpful information.

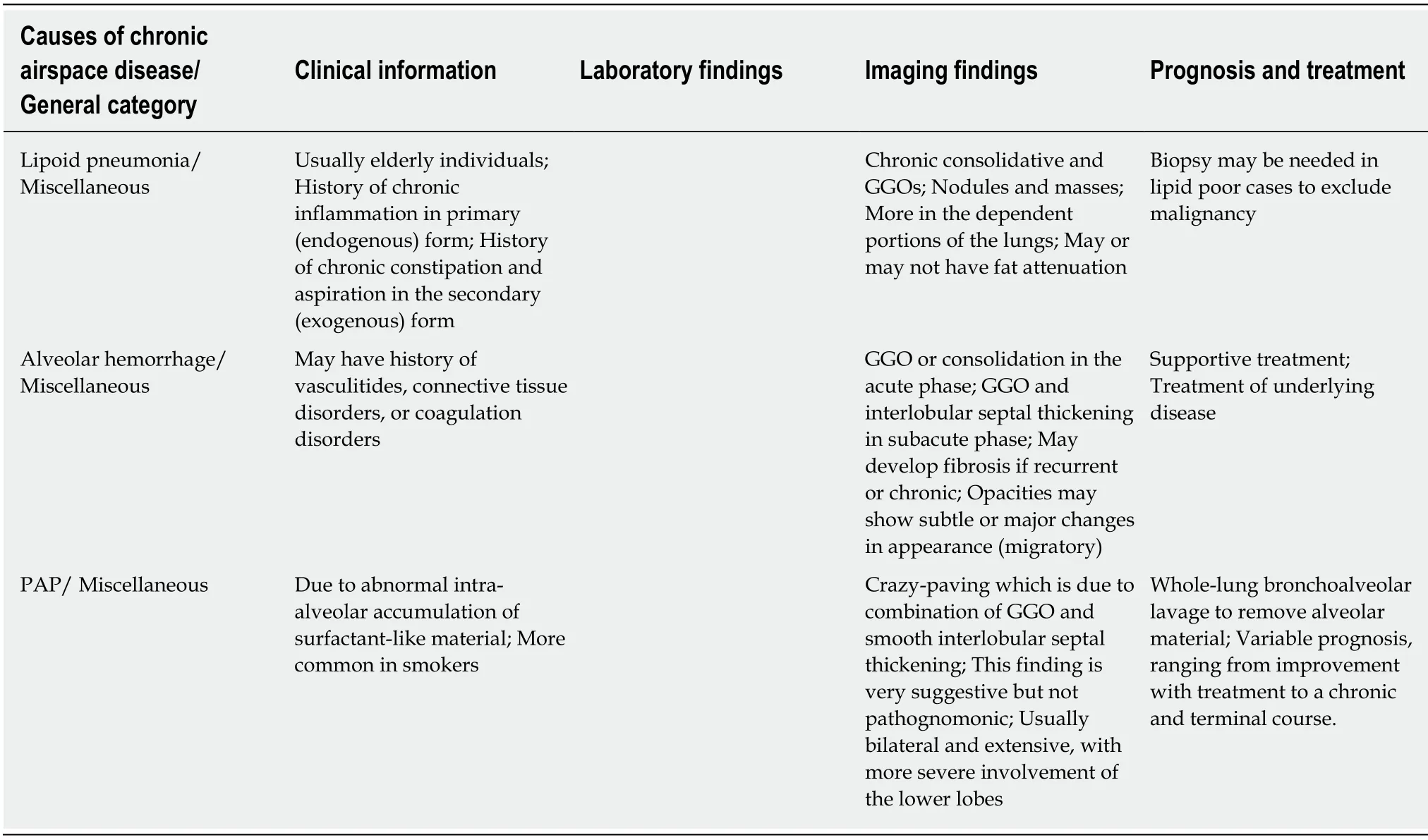

Table 1 Clinical,laboratory and imaging findings,and prognosis/treatment of inflammatory causes of chronic airspace disease

Table 2 Clinical,laboratory and imaging findings,and prognosis/treatment of infectious causes of chronic airspace disease

Presence of extrathoracic disease may shed light on the correct diagnosis (e.g.,renal or upper respiratory tract involvement in granulomatosis with polyangiitis,or involvement of liver and gastrointestinal tract in PTLD).Also,the presence of other ancillary imaging findings,such as presence and distribution of lymphadenopathy,presence of cavitation or presence of fat,can help (Tables 1-5).It should be noted that,while some imaging findings are suggestive and relatively specific for a diagnosis(e.g.,reverse halo sign in OP),they may not be very sensitive.

In the following sections,we will discuss the causes of chronic airspace disease and review the key clinical,laboratory and characteristic imaging findings that are helpful in making the diagnosis or in narrowing down the list of differential diagnosis.

Table 3 Clinical,laboratory and imaging findings,and prognosis/treatment of neoplastic causes of chronic airspace disease

INFLAMMATORY CAUSES

Alveolar sarcoidosis

Even though not a true airspace or alveolar process pathologically (noncaseating granulomas are mostly seen in the alveolar septa and around the small vessels),alveolar sarcoidosis can appear as persistent airspace opacities on imaging,mimicking intra-alveolar process.It is an atypical manifestation of thoracic sarcoidosis with estimated occurrence rate of 1%-4.4%[4].The more common and classic appearance of pulmonary sarcoidosis is upper-lung predominant and fairly symmetric perilymphatic nodules,while alveolar sarcoidosis presents as infiltrative and consolidative opacities with ill-defined margins and sometimes air bronchograms,or large nodules/masses that persist over time[5],mimicking infiltrative malignancies,such as multifocal adenocarcinoma or pulmonary lymphoma (Figure 1).Reverse halo sign with central GGO and peripheral rim of consolidation is well described in alveolar sarcoidosis[6].Also,interlobular septal thickening and GGO causing crazypaving pattern has been described[7](Table 1).

Alveolar sarcoidosis is associated with a more acute and symptomatic phase of thoracic sarcoidosis and is therefore expected to show a more severely increased metabolic activity on fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (commonly known as FDG/PET)[8].Active disease is treated with corticosteroids,generally giving a relative rapid response to the treatment; however,the disease may recur after discontinuation of treatment[4].

Table 4 Clinical,laboratory and imaging findings,and prognosis/treatment of miscellaneous causes of chronic airspace disease

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia

This is an idiopathic condition,more common in middle-aged women,and with a history of asthma present in up to 50% of patients[9].It is characterized by filling of the alveoli with an inflammatory,eosinophil-rich infiltrate[9].Increased serum IgE level is seen in two-thirds of patients and high erythrocyte sedimentation rate is also present.High eosinophil counts are seen in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid[9,10].

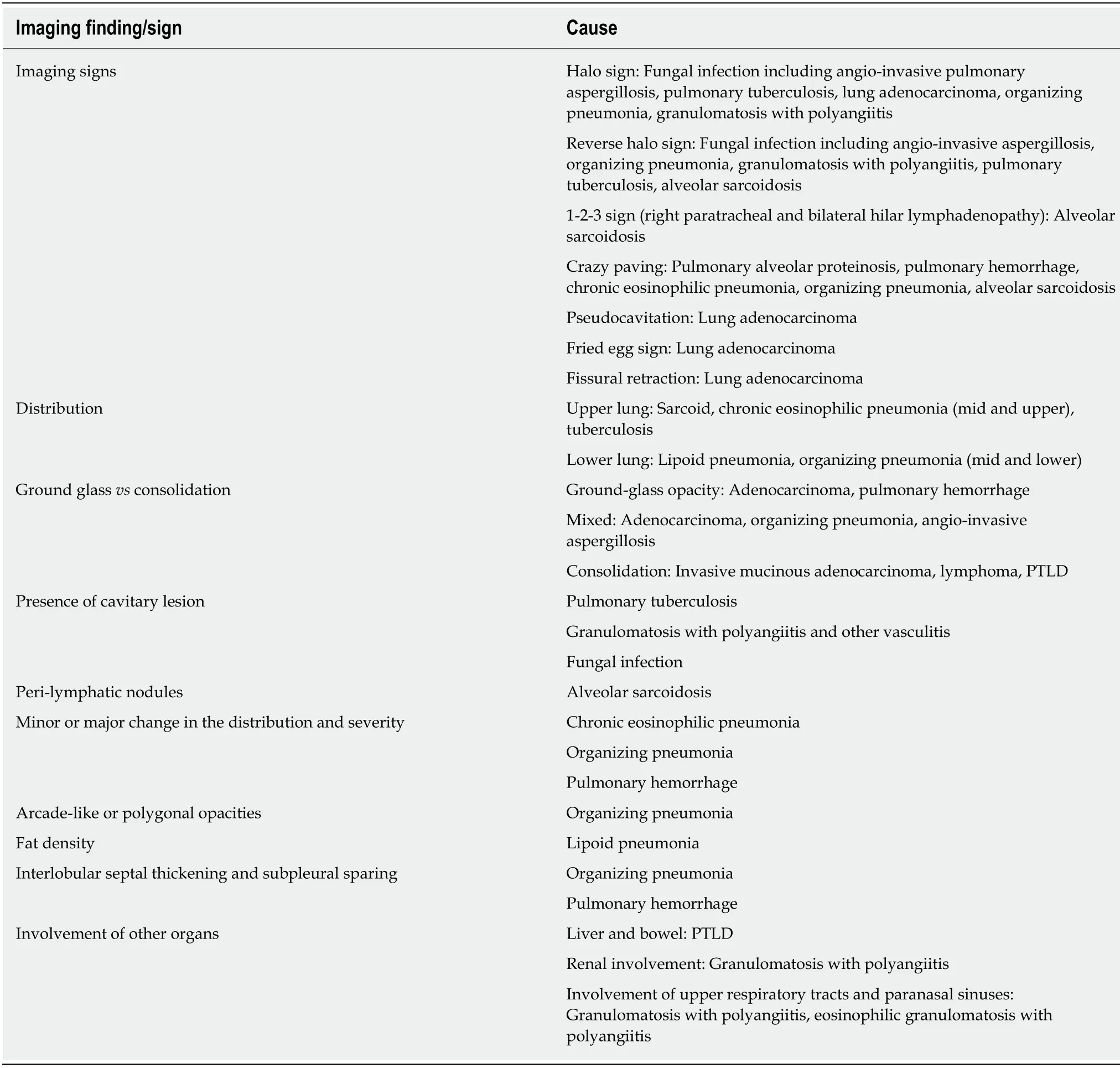

The typical imaging finding is presence of middle/upper and peripheral lung predominant chronic airspace opacity and consolidations[9].The opacities may persist over time but usually show subtle or major changes in appearance and therefore are migratory (Figure 2).Crazy-paving with GGO and interlobular septal thickening have also been described[7].

The diagnosis is based on respiratory symptoms,alveolar and/or blood eosinophilia,airspace opacifications,and exclusion of other causes of eosinophilic lung disease[10].Overall,chronic eosinophilic pneumonia carries a good prognosis.However,it often needs long-term low-dose corticosteroid treatment in order to prevent relapse[10].

OP and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) is a disease of unknown etiology that affects bronchioles and alveoli[11].The inflammatory process may cause bronchiolar occlusion.Hence,it was previously termed bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.A wide variety of infectious as well as noninfectious causes may result in a similar histologic pattern of OP,however the idiopathic form of OP is termed COP[11].

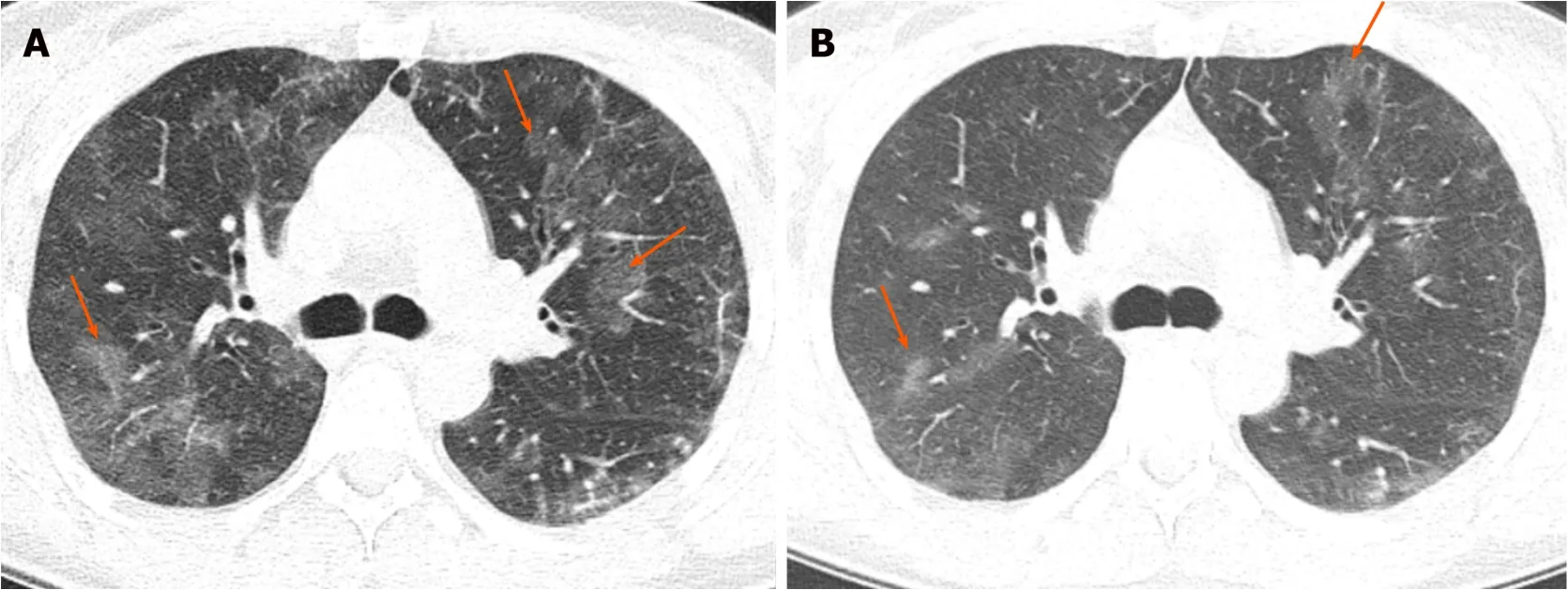

Even though OP or COP can present as small,ill-defined peribronchial or peribronchiolar nodules as well as large nodules or masses,the classic imaging finding is presence of bilateral peribronchovascular and/or subpleural consolidations with mid-lower lung zone preference[11](Figure 3).Reverse halo sign can be seen in 20% of the cases[12].The areas of consolidation may be migratory and show subtle or major changes in their appearance and distribution[11].In addition to the mentioned classic imaging findings,the presence of arcade-like or polygonal opacities are suggestive of this diagnosis[11].Interlobular septal thickening and GGO causing crazypaving pattern have also been described[7].Most cases,especially of the cryptogenic form,respond well to corticosteroid treatment.A small percentage of patients,however,may develop progressive fibrosis[11].

Table 5 Key imaging findings and imaging signs in chronic airspace disease

EGPA

Also known as Churg-Strauss syndrome,EGPA is a small to medium vessel necrotizing pulmonary vasculitis.It is characterized by hypereosinophilia and is almost exclusively seen in patients with asthma[13].

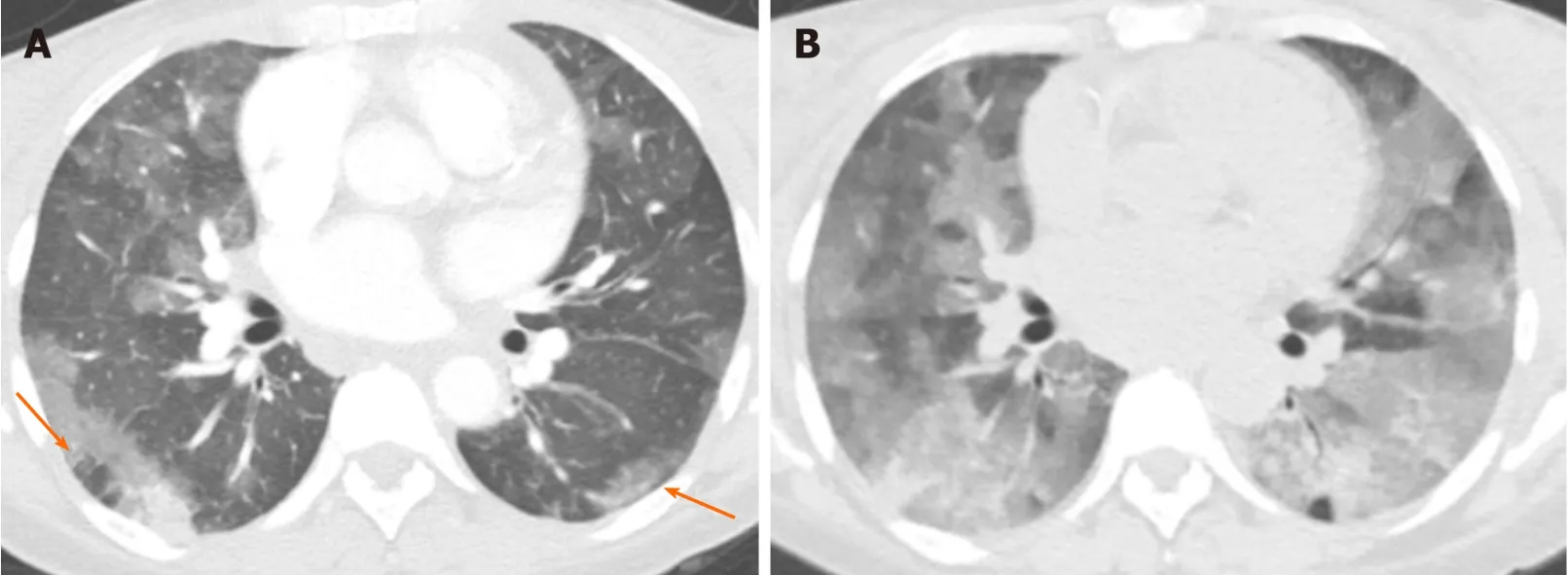

In addition to the pulmonary symptoms and asthma,patients also have such extrapulmonary findings as signs and symptoms related to sinusitis,diarrhea,skin purpura,and/or arthralgias.The most common imaging finding is peripheral or random parenchymal opacification,either as consolidation or ground glass,which can be transient and change in appearance and distribution in the follow-up imaging[13](Figure 4).There is no zonal predominance.Less common imaging findings are centrilobular nodules and bronchial wall thickening and/or dilatation.Cavitation is rare[13].

EGPA is treated with corticosteroids.Further immunosuppression with cyclosporine or azathioprine may be needed,especially in cases with cardiac,renal,gastrointestinal and central nervous system involvement[13].Even though the mortality is low,cardiac involvement is the major reason for death[13].

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis,previously known as Wegener granulomatosis,is a multisystem necrotizing noncaseating granulomatous c-ANCA-positive vasculitis affecting small- to medium-sized arteries,capillaries and veins[14].The vasculitis mainly involves the respiratory system,sinuses,and kidneys,and is slightly more common in men[14].

Immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide,methotrexate and corticosteroids is needed.Granulomatosis with polyangiitis can be rapidly fatal without treatment[14].

Figure 1 Alveolar sarcoidosis.

Drug-induced

Different medications,especially those for cancer-related treatment,can negatively affect the lung parenchyma.Lung response to these medications can appear as different patterns of chronic airspace disease,such as OP (bleomycin,methotrexate,amiodarone),nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (amiodarone,methotrexate),eosinophilic pneumonia (penicillamine,sulfasalazine,nitrofurantoin,nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs),and pulmonary hemorrhage (anticoagulants,amphotericin B)[15].In addition,newer anticancer agents,such as immune check inhibitors,can cause different patterns of pneumonitis and airspace diseases; these patterns include OP,nonspecific interstitial pneumonia,hypersensitivity pneumonitis,and acute respiratory distress syndrome[16](Figure 6).

Symptomatic and supportive treatment is the main part of treatment.However,there might be need to withhold the offending medication,depending on the severity of pneumonitis[16].

INFECTIOUS CAUSES

Angio-invasive aspergillosis

Pulmonary fungal infections are a relatively common complication in immunocompromised patients.Imaging findings can be variable,ranging from an airway-centered bronchopneumonia with associated tree-in-bud nodules to a more classic lobar or segmental appearing consolidation,with GGOs being the predominant findings in many cases[17].Most angio-invasive fungal pneumonias,including angio-invasive aspergillosis,manifest as parenchymal nodules or consolidation with a surrounding area of GGO (“halo” sign) that results from hemorrhage[18](Figure 7).In addition to the halo sign,reverse halo sign has been described in angio-invasive aspergillosis[19].Peripheral wedge-like areas of consolidation,representing hemorrhagic pulmonary infarcts,are also well described in these patients[18].Pleural effusion and lymphadenopathy are usually absent[20].In the correct clinical setting,which includes severe immunocompromised state with neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count < 500/μL),these findings are strongly suggestive of angio-invasive aspergillosis until proven otherwise[17](Table 2).

Figure 2 Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia.

As it may take days to weeks for cultures to yield results,radiologist input is critical in facilitating timely,targeted therapy.Treatment is usually with intravenous amphotericin B.Without early diagnosis and prompt treatment,prognosis remains poor[17].

Pulmonary tuberculosis

Imaging findings in primary pulmonary tuberculosis are nonspecific and can range from an almost undetectable area of small airspace opacity to patchy areas of consolidation or even lobar consolidation[21].However,cavitation is uncommon in this phase[21].Post-primary tuberculosis is more symptomatic clinically,with more profound imaging manifestations,and usually presents many years after the primary infection; the latter is usually due to compromise in the patient's immune status.Moreover,it is usually seen in the posterior segments of the upper lobes or superior segments of the lower lobes.

Imaging findings are variable,but the typical appearance of post-primary tuberculosis is that of patchy consolidation with or without GGO (halo or reverse halo sign) or poorly defined linear and nodular opacities which persist and may cavitate in up to 40% of the cases[21].Areas of cavitation may communicate with the airways resulting in endobronchial spread of infection and tree-in-bud appearance[21],suggesting a highly contagious form of disease (Figure 8).

亚抑菌浓度抗菌药物对多重耐药鲍曼不动杆菌生物膜形成的影响 ………………………………………… 樊 莉等(22):3129

Treatment is with multiple antibiotics,based on the sensitivity of the organism.

Non-tuberculosis mycobacterium avium complex infection:The incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease in the United States and Canada has been increasing and this is mainly due to mycobacterium avium complex organisms[22].Although this infection can happen in patients with pre-existing pulmonary disease or depressed immunity,it has been increasingly reported in otherwise healthy individuals,especially in elderly women[23],and may be due voluntary suppression of the cough reflex (Lady Windermere syndrome).

Two main forms of pulmonary mycobacterium avium complex infections have been described.The first is the upper lobe fibrocavitary form,which has a more rapid and aggressive course,and needs prompt treatment.The second is the nodular bronchiectatic form,which tends to progress more slowly,and the diagnosis of the disease does not require immediate treatment and may be managed with observation alone.

In addition to the upper lobe cavitary lesions and right middle lobe/lingular bronchiectasis,CT findings include persistent patchy consolidation and ground glass patchy opacities[22](Figure 9).

There is no clear gold-standard for treatment.Patients may be followed if asymptomatic.Symptomatic cases usually need multiple antibiotics.Surgical resection can be an option in localized disease[22].The disease has a more aggressive course in the upper lung fibrocavitary form,while showing a more indolent course in the nodular bronchiectatic form[22].

Figure 3 Organizing pneumonia.

Incompletely treated bacterial infection

Partially treated bacterial infection can present as an area of consolidation that is persistent with some or minimal improvement on follow-up imaging.This should be suspected when a patient with a proven diagnosis of bacterial infection is still symptomatic and the imaging findings are more or less unchanged.

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

Pneumocystis jiroveciipneumonia is an atypical pulmonary infection,which almost never happens in immunocompetent individuals but is one of the most common causes of life-threatening pulmonary infections in human immunodeficiency viruspositive patients.It typically occurs at CD4 counts < 200 cells/mm[24].Other patient populations that are at increased risk ofPneumocystis jiroveciipneumonia infection are post-transplant patients,patients with hematologic malignancies,patients undergoing chemotherapy for malignancy,and patients undergoing long-term corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory and connective tissue diseases,such as Wegener granulomatosis and systemic lupus erythematosus[25].

The principal finding on chest CT is GGO,mainly with perihilar or mid zone distribution (Figure 10).Depending on presence or absence of prophylactic aerosolized medication; mid,upper or lower zone involvement may be dominant[24].Other imaging findings include septal thickening and therefore crazy paving and pneumatoceles.Pleural effusion and lymphadenopathies are uncommon.Consolidation and cavitation are more atypical and seen mainly in patients who are on prophylactic treatment[26].

Most patients with acute infection are treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole,combined with corticosteroids in moderate to severe infections[27].Trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole is also used as a prophylactic regimen[27].

NEOPLASTIC CAUSES

Adenocarcinoma

Lung adenocarcinoma is the most common histologic subtype of lung cancer.It is classified as adenocarcinomain situ,minimally invasive adenocarcinoma,or invasive adenocarcinoma (Table 3).

Adenocarcinomain situand minimally invasive adenocarcinoma are seen as predominantly GGO ≤ 3 cm,with or without a small solid nodular component,that persist over multiple follow-up CT scans and show gradual and slow growth[28].Presence of GGO with associated solid component is described as fried-egg sign[29,30](Figure 11).FDG-PET/CT may be falsely negative for smaller lesions or show only mildly increased metabolic activity for larger lesions[28](Figure 11).Pseudocavitation has been described as a well-recognized feature of adenocarcinomain situand minimally invasive adenocarcinoma[29]and refers to the central bubble-like lowdensity region seen within a pulmonary nodule on CT.Fissural or pleural retraction can also be seen with these tumors[30].Hilar and mediastinal adenopathy and pleural effusion are uncommon at this stage[30].

Invasive adenocarcinoma appears as a solid or subsolid and sometimes even ground glass nodule or mass.The ground glass area corresponds to a lepidic growth pattern and the solid component corresponds to invasive patterns[31].Persistent airspace opacity and consolidation with air-bronchogram,mimicking pneumonia,has been mostly described in the invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma subtype that was formerly called mucinous bronchoalveolar adenocarcinoma[32](Figure 12).Other imaging findings described in this variant are multifocal subsolid nodules or masses[33].

Figure 4 Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Pulmonary lymphoma

Pulmonary lymphoma refers to lung parenchymal involvement with lymphoma and can be categorized as primary or secondary.Primary pulmonary lymphoma is rare and is usually non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.It is limited to the lung and there is no evidence of extrathoracic involvement for at least 3 mo after the diagnosis[34].Secondary pulmonary lymphoma,on the other hand,is relatively common and can be Hodgkin's lymphoma or non-Hodgkin's lymphoma[34].

Mass or mass-like consolidation > 1 cm with or without cavitation or airbronchogram has been described as the most common imaging finding of pulmonary lymphoma[34](Figure 13).Other less common findings are pleural-based mass,small(< 1 cm) nodules,alveolar or interstitial infiltrate,pleural effusion,and hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy[35].

Patients are treated with chemotherapy and radiation.Surgical resection can be done for localized disease.Pulmonary lymphoma carries a good prognosis[34].

PTLD

PTLDs are uncommon complications following organ transplantation,affecting 10%of cases after solid organ transplant[36].They include a variety of conditions ranging from lymphoid hyperplasia to malignancy and can be manifest a life-threatening condition.The incidence varies depending on the type of transplanted organ,with the highest incidence reported after small bowel transplant.The disease can be focal or systemic,and can affect any organ system and even the allograft.Liver is the most common organ to be involved[37]but other organs,such as small bowel,colon and lungs,are commonly involved[37].

Pulmonary findings of PTLD include pulmonary nodules and masses which may cavitate,with pulmonary consolidation in 55% of the cases and intra-thoracic lymphadenopathy in 45% of cases[36](Figure 14).

The choice of treatment depends on severity,location and extent of the disease.Treatment options include,reduction in immunosuppression,resection of localized disease,radiation treatment,and/or chemotherapy[37].Negative serology for Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus at the time of the transplant increases the risk of PTLD[36].

Pulmonary metastasis

Although the most common pattern of pulmonary metastases is multiple pulmonary nodules with random distribution,persistent air-space opacity can be an unusual appearance of lung metastasis[38].This pattern can be seen with adenocarcinomas of gastrointestinal tract origin but can also be seen in adenocarcinomas originating from the breast and ovary (Figure 15).This pattern is due to tumoral spread into the lung along the intact alveolar walls (lepidic growth),in a fashion similar to invasive primary adenocarcinoma of the lung.

Figure 5 Granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

MISCELLANEOUS

Lipoid pneumonia

Lipoid pneumonia is uncommon and can mimic the clinical and imaging features of other lung diseases,including primary lung carcinoma.Imaging findings of lipoid pneumonia include chronic consolidative and GGOs as well as nodules and masses,more in the dependent portions of the lungs,and the possible presence of fatty attenuation[39](Figure 16).Fatty attenuation may be absent,especially in the setting of chronic inflammation,and therefore tissue sampling may be needed to exclude malignancy[40].Lipoid pneumonia can be exogeneous secondary to aspiration of oily materials or endogenous because of chronic accumulation of lipid substances,usually in the setting of chronic inflammation[39](Table 4).

Treatment is supportive and also targets the underlying chronic inflammatory condition in the primary form or chronic aspiration in the secondary form[40].

Pulmonary hemorrhage

Pulmonary hemorrhage can be diffuse or localized.It can be due to a vast number of clinical situations,including pulmonary vasculitides,connective tissue disorders,coagulation disorders,and anticoagulation medication.The condition can also be life threatening,especially when diffuse[41].

In the acute phase,bleeding into the alveoli can range from GGO to consolidation[41].Interlobular septa may remain dark as they are not filled with blood or fluid in the acute phase.The distribution and severity of opacification can change with time (Figure 17).In the subacute phase,interlobular septal thickening can be superimposed on GGO and may sometimes cause crazy-paving appearance[7].Subpleural sparing can be seen in both acute and subacute phases[7].Chronic recurrent bleeding can cause ill-defined centrilobular nodules,and pulmonary fibrosis if long standing[42].

Treatment of pulmonary hemorrhage is supportive and addresses the underlying etiology.

Pulmonary alveolar preoteinosis

Pulmonary alveolar preoteinosis is a rare disease characterized by abnormal intraalveolar accumulation of surfactant-like material[43].The characteristic imaging finding of pulmonary alveolar preoteinosis on CT is crazy-paving,due to combination of GGO and smooth interlobular septal thickening[44](Figure 18).Although this finding is very suggestive,it is not pathognomonic and many other infectious,hemorrhagic,neoplastic,inhalational and idiopathic conditions can produce the same pattern[44,45].It is usually widespread and bilateral,with slight lower lung predominance[45].The severity and extent of GGO or consolidation on CT correlates with severity of compromised pulmonary functional parameters[45].In addition to crazy-paving,areas of consolidation may be seen[44].

Whole-lung bronchoalveolar lavage is used to remove alveolar material.The prognosis is variable,ranging from improvement with treatment to a chronic and terminal course[44].

The key imaging findings and imaging signs in chronic airspace disease are summarized in Table 5.

Figure 6 Pembrolizumab-induced pneumonitis.

CONCLUSION

Chronic airspace diseases can cause significant diagnostic challenge due to significant overlap in their imaging findings.Knowing the imaging features and combining them with the clinical and laboratory findings can be helpful in steering the radiologist to the correct diagnosis.

Figure 7 Angio-invasive aspergillosis.

Figure 8 Mycobacterial tuberculosis.

Figure 9 Mycobacterium avium complex infection.

Figure 10 Pneumocystis jirovecii infection.

Figure 11 Adenocarcinoma in situ.

Figure 12 Invasive adenocarcinoma.

Figure 13 Pulmonary lymphoma.

Figure 14 Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Figure 15 Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas.

Figure 17 Pulmonary hemorrhage.

Figure 18 Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis.