Ancient Poetry Shines

By Li Qing

A 7-year-old girl recites Welcome Rain on a Spring Night, a poem from the Tang Dynasty (618-907), in front of a thatched cottage in Chengdu, Sichuan Province in southwest China. “The good rain knows its season, when spring arrives. It brings life… Dawn sees this place now red and wet, the fl owers in Chengdu are heavy with rain.”

The cottage is one of the most famous attractions for literary pilgrims from all over the country. Its long-ago dweller Du Fu (712-770), author of Welcome Rain on a Spring Night, is a legendary poet who has greatly influenced China for over a 1,000 years.

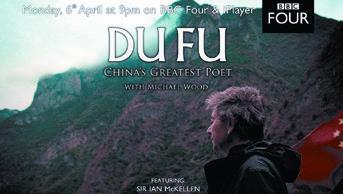

The scene is part of Du Fu, Chinas Greatest Poet, a BBC documentary first aired in April. Directed by Michael Wood, a historian at the University of Manchester, it presents Dus life and literary achievements.

Wood says in front of the camera that he is surprised to see such a young fan of Dus poetry, and wonders how she could even understand his work. Her mother, a poetry lover, replies, “I want her to be infl uenced by our ancient culture,” adding that she chooses simple pieces for her daughter that are easy to learn and recite.

In China, children know Dus poems, while in East Asian culture he is revered. However, Du has remained relatively unknown in other parts of the world. But now, thanks to the fi rst English documentary on the poet, his life and work, as well as traditional Chinese cultural values, have been unveiled for Western viewers.

“To call him a poet is to downplay his importance in Chinese literature because it limits his standing simply to that of a poet,” Wood says in the documentary. “There is no comparable fi gure in Western culture, someone who, by chance as it turned out, came to embody not only the feelings but the moral sensibility of a whole civilization.”

A historical life

China has the oldest living tradition of poetry in the world—more than 3,000 years old—preceding Homers Iliad and Odyssey. For Chinese people, Du is their greatest poet, Wood explains.The documentary travels in the poet-sages footsteps, connecting his extraordinary life and times with his words, and asking Chinese to provide their thoughts on him. People praise his writing style and the fact that he was the voice of ordinary people. One person says Du represented the Chinese cultural identity, which can make people traveling abroad feel proud of their motherland and, at the same time, make them feel nostalgic.

Born to a wealthy family, Du grew up during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong (713-756), which was a cosmopolitan time of prosperity, inclusiveness and cultural accomplishment. He showed his literary gift at a very young age. “When I was still only in my seventh year, my mind was already full of heroic deeds. My first poem was about the phoenix. The harbinger of a sagacious reign, a new age of wisdom,” Du wrote.

Under the infl uence of Confucianism, which emphasizes virtue, benevolence and service to the country, Dus ambition was to pursue a successful offi cial career. Due to his early poetic success, he was confident about his future. “I feared no rival among the competing scholars, nor any diffi cult question that might be put to me,” he proclaimed. However, his dreams of“climbing to the top and restoring the purity of culture and civilization” were thwarted by failures in imperial exams.

In a turn of events, however, the emperor summoned him after reading his poems and appointed him in his court. In his 60s at the time, the emperor was growing negligent and promoting corrupt ministers. Again Dus dream of being a virtuous official and contributing to the good of the country was obstructed.

Meanwhile, the empire was falling into crisis. Higher taxes and mass conscription led the poor toward growing social unrest. Natural disasters, such as heavy storms and fl oods, followed by famine, added to the misery. “Behind the red lacquered gates, wine is left to sour, meat to rot. Outside the gates, lie the bones of the frozen and the starved,” Du wrote, criticizing the disparity between the extravagant life of the rich and the wretched life of the poor.

Chinese people, who value the recording of history, regard Du as one of the best at refl ecting his times in his poetry. This was due to the fact that historical events mirrored his own life and spiritual journey, Zeng Xiangbo, a professor of ancient Chinese literature at Renmin University of China, told China Daily.

In 755, a rebellion led by powerful warlord An Lushan eventually led to an eight-year civil war. To escape from the war and the following chaos, Du wandered around the country with his family for the last 15 years of his life. These hardships did not keep him from writing, but it did provide a turning point in his creativity, making his work heavier and more realistic.

“I think you identify with him much more than before because you see him as a helpless pawn amid epic events happening all around him,” Liu Taotao, a retired Oxford University lecturer, said. Despite his tribulations, Du showed a positive attitude, focusing on the pure joy of nature and life, but never forgetting the suffering of the people.

“ Could I get mansions covering 10,000 miles, Id house all scholars poor and make them beam with smiles,” he wrote in the thatched cottage on a rainy night when “the roof leaks over beds, leaving no corner dry.”

In the documentary, Du is put in the same literary league as Dante and William Shakespeare. “These poets created the very values by which poetry is judged,” Stephen Owen, a Harvard professor and Sinologist, said.

Narrative of Chinese culture

Many viewers in the UK said the documentary opened their eyes to an aspect of Chinese culture that they were unaware of, Wood told Xinhua News Agency. “They did not know China had the oldest living continuous tradition of poetry in the world.”

However, criticism of the documentary also emerged. For instance, some argued that the chosen translations lacked elegance, while others thought the documentary should have included more poetry rather than so many details about Dus life.

The documentary is expected to arouse peoples interests in Dus poetry and make his masterpieces more accessible to a broader readership, Yu Yaqin, a fi lm critic, told Economic Observer, a Beijing-based business weekly.

“In the past, some Western documentaries featured Chinese culture with a certain Western curiosity and imagination, failing to convey the nature of Chinese culture and making us feel misunderstood or disrespected,” Yu said.

A fan of Chinese culture who read poems from the Tang Dynasty as a teenager, Wood has abundant knowledge of China and is believed to be able to incorporate a Chinese perspective. In addition, he has produced other documentaries such as The Story of China (2016) and The Story of Chinas Reform and Opening Up (2018), where he tries to bring out the connections and mutual influences between Chinese and Western culture in a bid to decode the abstract and profound Chinese culture.

“In contrast to the traditional narrative, which focuses on the historical background or signifi cance of the works, the documentary highlights common humanity and public emotion,” Wu Mingzhou, Dean of Jiangsu Ocean Universitys Art College, told Beijing Review.

People share similar feelings about family, friendship and love for their country, which can transcend cultural gaps and make up for the limitations of translation, he said. The positive ideas and human feelings expressed in Dus poetry, such as resilience in adversity, can help people get through hard times.

Some people in the West on lockdown due to the novel coronavirus pandemic wrote to the documentary team, saying they had been inspired by the poetry and wanted to explore it deeper.

For Wood, making this documentary not only provided a vehicle to showcase Dus life and his literary achievements, but also showed how his work infl uenced and recorded the development of traditional Chinese values. Du can provide a reference for the world to get to know China and its people better, he told Xinhua.