Two-Year Observation of Fossil Fuel Carbon Dioxide Spatial Distribution in Xi’an City

Xiaohu XIONG, Weijian ZHOU, Shugang WU, Peng CHENG, Hua DU, Yaoyao HOU,Zhenchuan NIU,4, Peng WANG, Xuefeng LU, and Yunchong FU

1State Key Laboratory of Loess and Quaternary Geology, Institute of Earth Environment,Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi'an 710061, China

2Shaanxi Key Laboratory of AMS Technology and Application, Xi'an AMS Center, Xi'an 710061, China

3Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710049, China

4Chinese Academy of Sciences Center for Excellence in Quaternary Science and Global Change, Xi’an 710061, China.

5Open Studio for Oceanic-Continental Climate and Environment Changes, Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao), Qingdao 266237, China

ABSTRACT

Key words: fossil fuel CO2, 14C, Xi’an, carbon emissions reduction, Setaria viridis

1. Introduction

Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) reached a new level in 2017 (405.5 ppm), equal to 146% of the pre-industrial level, and is mainly attributed to anthropogenic fossil fuel emissions (WMO, 2018). Global net anthropogenic CO2emissions should decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 to limit global warming to below 1.5°C (IPCC, 2018).Therefore, reliable methods to quantify anthropogenic CO2emissions are essential. Two methods have been commonly applied: “bottom-up” and “top-down.” The former is based on activity data and emission factors (IPCC, 2006). The reliability of this method not only depends on the quality of statistical activity data, but also on the accuracy of emission factors (Liu et al., 2015). The estimated uncertainty of the“bottom-up” method has been estimated to range from a few percent to about 50% on an individual national scale(Andres et al., 2012); and may be as high as 100% on an urban scale (Gurney et al., 2009; Peylin et al., 2011; Turnbull et al., 2011). The “top-down” method usually measures the atmospheric CO2mixing ratio from ground stations (Levin et al., 2003), aircraft (Turnbull et al., 2016) or satellites (Buchwitz et al., 2017). This approach can produce high temporal and spatial resolutions using CO2data.However, observed CO2fluctuations do not directly measure fossil fuel CO2(CO2ff) emissions, as both CO2ffand natural CO2(e.g., from heterotrophic respiration) can contribute to atmospheric CO2variations.

Radiocarbon (14C) is a unique and powerful tracer for CO2ffand a useful tool to verify “bottom-up” inventory estimates (Levin et al., 2003; Nisbet and Weiss, 2010; Turnbull et al., 2016). Δ14C in plants has been widely used to represent mean daytime atmospheric Δ14C during their growth period for quantification of atmospheric CO2ff(e.g. Lichtfouse et al., 2005; Bozhinova et al., 2013; Turnbull et al., 2014).Plant samples are easier to collect in a large area at low cost, as compared with air samples (Turnbull et al., 2014),and are especially advantageous when focusing on the spatial distribution of CO2ff(Hsueh et al., 2007; Riley et al.,2008). Cities, with concentrated carbon emissions and frequently affected by serious air pollution meanwhile, have been recognized as playing a key role in the action of climate change mitigation (Rosenzweig et al., 2010; Hoornweg et al., 2011). The spatial distribution of CO2ffindicated by plants has been investigated in a few cities (Xi et al.,2011, 2013; Djuricin et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2014; Beramendi-Orosco et al., 2015; Niu et al., 2016); however, very few city centers have been targeted, because of the lack of particular species (e.g., corn leaves were chosen in many studies) in city centers. Interannual CO2ffvariations and their spatial distribution based on plants is also scarce (Bozhinova et al., 2016). Green foxtail samples have been successfully used to reflect CO2ffdifferences in some areas in Xi’an City in 2010 (Zhou et al., 2014). In this study, green foxtail was sampled across a wide distribution of sites in the central urban area of Xi’an in 2013 and 2014 to investigate the atmospheric CO2ffspatial distribution and its year-to-year variation. These data were used to quantify the spatial distribution and to estimate the influencing factors. The main goal was to provide quantitative information that can be used to improve local carbon emission reduction measures.

2. Methods

2.1. Study sites and materials

Xi’an is a famous tourist city and a significant node city of “the Belt and Road” initiative in the west of China.Its resident population reached 10 million in 2018. This city experiences a semiarid continental monsoon climate, with a mean annual temperature of 13.0°C—13.7°C. The mean annual rainfall is 522.4—719.5 mm, with over 80% of the precipitation falling in May to October. The winds are characteristically mild in Xi’an, with a prevailing northeasterly wind direction.

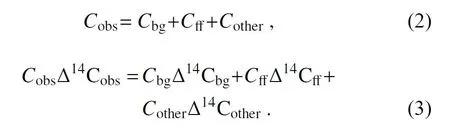

Annual plant samples [green foxtail, Setaria viridis (L.)Beauv.] from 26 sites inside the Xi’an Bypass Highway were collected in parks or scenic spots in October of 2013 and 2014. The distribution of these sites is shown in Fig. 1.Green foxtail is a C4 plant species, widely distributed in the city green belt as weeds. Its growing period is April to September in Xi’an City; thus, it reflects average atmospheric CO2ffin the late spring—summer—early autumn in general. Every location sample was mixed by two or three individual plants with seed maturation, and all of them grew in open areas with good ventilation, as far as possible from urban trunk roads. Plant materials were air-dried before pretreatment.

2.2. Experiment

The grass leaves were soaked with 1-mol L-1hydrogen chloride at 70°C for 2 h to remove any adhering carbonate,then rinsed with deionized water until neutral, and dried at 60°C. The dry plant materials (4—5 mg) were mixed with copper oxide (~200 mg) in a quartz tube and combusted at 850°C for 2 h under vacuum (~100 Pa). Finally, the CO2was extracted using liquid nitrogen as a cryogen, and further purified with liquid nitrogen/alcohol (-75°C) to remove water. The purified CO2was reduced to graphite carbon using zinc as a reductant over an iron catalyst. The produced graphite was pressed into an aluminum holder and measured in a 3-MV Accelerator Mass Spectrometer (High Voltage Engineering Europa B.V.) at the Xi’an AMS Center. Oxalic acid-II (NIST SRM 4990c) and coal were used as reference and blank, respectively. The measurement precision of a single sample is about 3‰ (1σ).

The14C results were calculated as Δ14C values, according to the equation (Stuiver and Polach, 1977)

where (14C/12C)sampis the14C/12C ratio of samples corrected for radioactive decay and normalized to a δ13C of-25‰, and (14C/12C)refis the14C/12C ratio of the reference standard.

2.3. Calculation of CO2ff

Atmospheric CO2(Cobs) can be considered to consist of three sources: (1) background CO2(Cbg), (2) fossil fuelderived CO2(Cff), and (3) other CO2sources (Cother). According to mass balance:

Fig. 1. The distribution of green foxtail sampling sites in the Xi’an urban area.Twenty-six sites (solid circles) were in the parks or in the scenic spots in the central urban district of Xi’an City. Two thermal power plants (solid triangles) were in the east and west area outside of the second Ring Road. The region inside the Bypass Highway was divided into three parts by the Ring Road and the second Ring Road,namely, Area I, II and III, respectively.

For time-integration, as in the case of seasonal plants,Cobscannot be determined. Thus, Eq. (2) is substituted into Eq. (3), resulting in

The second term in this expression is usually omitted,because the error introduced is small (Turnbull et al., 2015).Equation (4) can then be simplified, and Cffcan be calculated by the following widely used formula:

In this equation, Cffand Cbgare CO2derived from fossil fuel and CO2represented by background measurements, respectively; and Δ14Cobsis measured in the plant samples. Because there is negligible14C in fossil fuel, the end-member value of Δ14Cff= -1000‰ is assumed according to the definition of Δ14C [Eq. (1)]. Cbgrecords were obtained from measurements made in the Mauna Loa Atmospheric Baseline Observatory in Hawaii, the United States(Tans and Keeling, 2019), and background Δ14C data were from Jungfraujoch Atmospheric Baseline Observatory in Switzerland (Hammer and Levin, 2017).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Spatial variation of CO2ff in 2013

CO2ffresults from all sites in 2013 are shown in Fig. 2.The range of CO2ffwas 15.6—24.6 ppm, with an average of 20.1 ± 2.4 ppm. The average inside the Ring Road (5 sites,Area I), the Ring Road to the second Ring Road (6 sites,Area II) and the second Ring Road to the Bypass Highway segment (15 sites, Area III) were 19.8 ± 1.9 ppm, 19.6 ± 1.9 ppm and 20.4 ± 2.6 ppm, respectively. There were some sites with high CO2ffvalues, such as the Southwest Xi’an City Wall (SWXW), Changle Park (CLP), Yongyang Park(YYP) and Yanming Park (YMP). These sites were scattered, but mainly located in the south of the Xi’an urban area. In contrast, sites with relatively low CO2ffvalues were in the north, near the Bypass Highway. For example, the City Sports Park (CSP), Yuanjiabu Village (YJB), Xi’an World Horticulture Exposition Park (XEP), and the Epang Palace Relic Park (EPRP).

3.2. Spatial variation of CO2ff in 2014

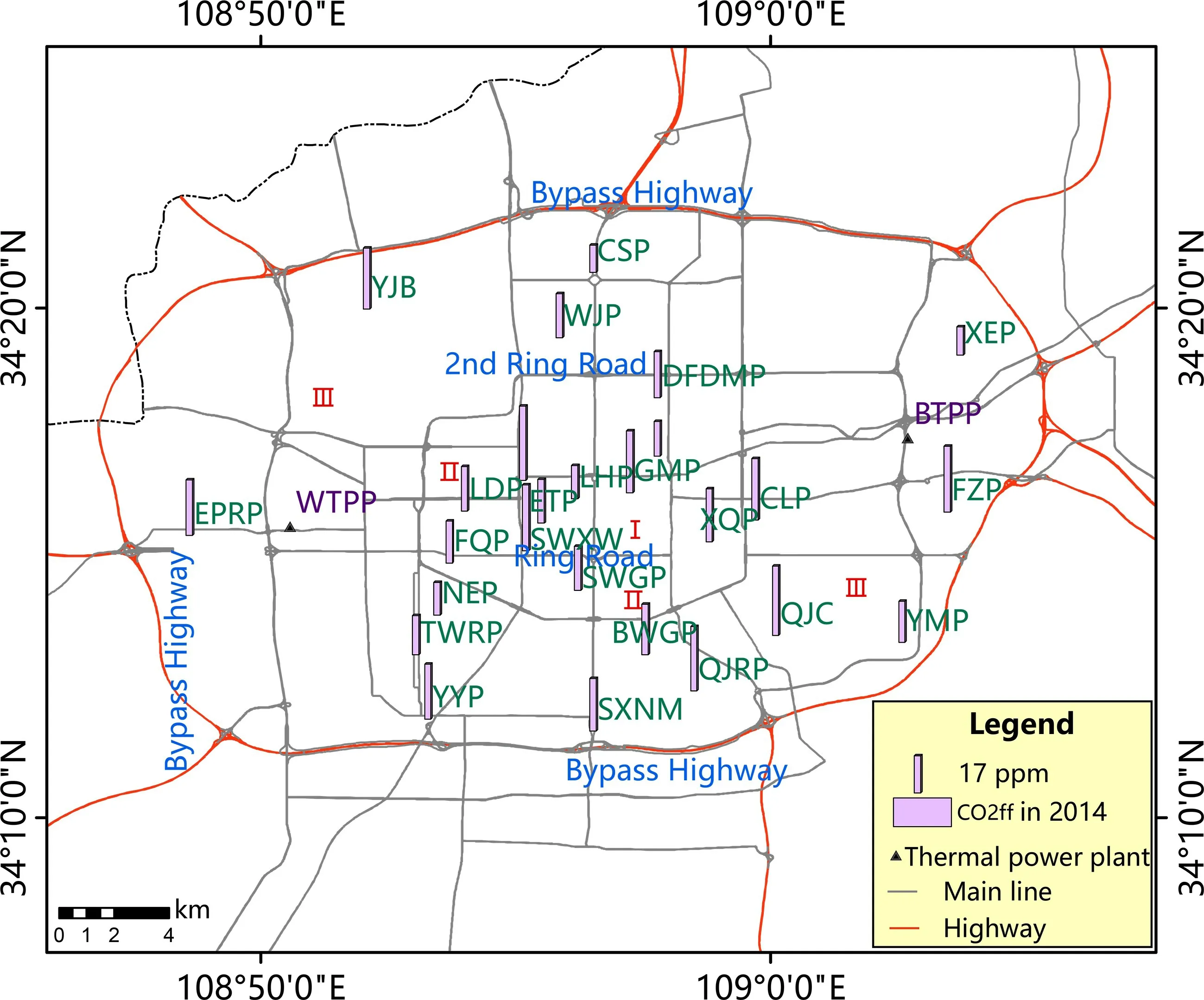

The spatial variations of CO2ffin 2014 are shown in Fig. 3. In 2014, the average CO2ffof all sites was 22.1 ± 5.4 ppm. The highest CO2ffvalue was 31.7 ± 1.5 ppm, and the lowest was 12.5 ± 1.5 ppm. The average CO2ffvalues of the above-mentioned three regions divided by the city’s ring roads were 22.9 ± 5.5 ppm, 20.1 ± 2.5 ppm and 22.7 ± 6.1 ppm, respectively, without statistically significant differences. As shown in Fig. 3, both of the higher, and lower,CO2ffvalues existed in the region inside the Ring Road,with a similar pattern within the second Ring Road to Bypass Highway area. It is interesting to note that the sites with higher CO2ffvalues were widely distributed in the area adjacent the Bypass Highway, except for the northeast corner, with the two lowest values (City Sports Park and Xi’an World Horticulture Exposition Park).

3.3. CO2ff variation from 2013 to 2014

Fig. 2. CO2ff mixing ratio spatial distribution in 2013. The value of CO2ff is proportional to the height of the light blue column.

Fig. 3. CO2ff mixing ratio spatial distribution in 2014. The value of CO2ff is proportional to the height of the pink column.

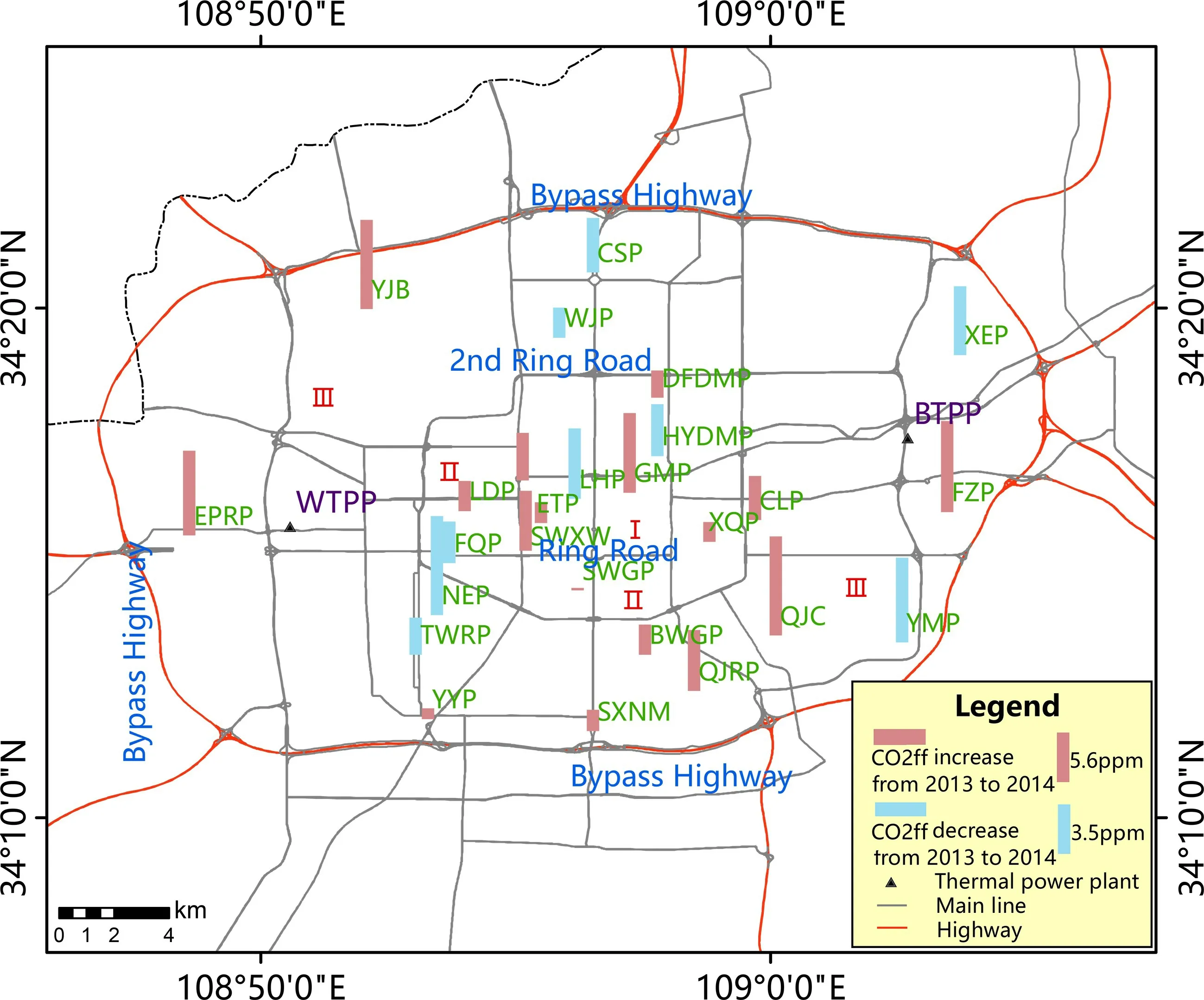

A comparison of both years showed that CO2ffvariation in 2014 was larger than in 2013; the variation coefficients were 24% and 12%, respectively. Moreover, the differences between 2013 and 2014 were statistically significant(P < 0.01, paired t-test) (Fig. 4). In detail, CO2ffvalues at eleven sites increased from 2013 to 2014, and six decreased.Only nine sites showed minor changes. CO2ffvariations in Area II sites were smaller than observed for the other two areas. It is worth noting that most sites close to the Bypass Highway showed obvious increases, with two exceptional cases in the northeast: the City Sports Park and Xi’an World Horticulture Exposition Park. Further, CO2fffrom these two sites had the lowest values observed in both 2013 and 2014.

3.4. CO2ff differences between Chinese cities

The CO2ffmixing ratio was about 10—30 ppm in the Xi’an central urban district in 2013 and 2014, similar to that reported for 2010 (Zhou et al., 2014), and very close to downtown Beijing in 2009 (Niu et al., 2016). However, the Xi'an value was higher than that observed in some small and medium-sized cities (e.g., Lhasa, Jiuquan, Erdos, Luochuan,Linfen and Yantai); CO2ffin these cities were generally lower than 10 ppm in 2010 (Xi et al., 2013). The likely implication is that cities with large populations have higher CO2emissions.

3.5. The effect of emission sources

The dominant CO2ffsources in the Xi’an urban district include thermal power plants, vehicle exhaust, and residential emissions. There are two thermal power plants in the investigated area, as shown in Fig. 1: Baqiao Thermal Power Plant (BTPP) in the east, and Western Thermal Power Plant (WTPP) in the west. We found that the CO2ffmixing ratio of the sites in the downwind area (southwest)near BTPP and WTPP, such as Changle Park (CLP),Xingqing Palace Park (XQP) and Epang Palace Relic Park(EPRP), was not especially elevated, when compared to results from the other regions. This might be attributable to enhanced diffusion of exhaust gas during transport from the very high power plant vents to the ground (Zhang, 2013).Our results suggest, therefore, that these two power plants are not primary contributors to CO2ffspatial variation.

Vehicle exhaust and residential emissions are non-point sources of CO2ffemissions. In general, they are widely distributed within the urban area. In addition, vehicle exhaust is a mobile emission source, which is distinct from residential emissions. Nevertheless, both are closely associated with population density. The two sites (CSP and XEP) with the lowest measured CO2ffvalues were located in an area in the northeast with low population density. In contrast, relatively high CO2ffvalues were frequently observed in the south of Xi’an,which includes two of six population centers in this district(Mi et al., 2014). The rapid increase of motor vehicles during 2013—14 (from 1.6349 million to 1.9260 million) but overall slow residential population growth (from 5.8060 million to 5.8716 million) suggested that CO2ffincreases observed for many sites were likely related to rapidly growing regional traffic conditions. For example, the Ring Road was under construction, with the addition of three tunnels, to improve the traffic in 2013. This project was completed in April 2014, at which point traffic flow increased rapidly. As a result, at sites SWXW and NWXW, adjacent to the Ring Road, the CO2ffmixing ratio rose from ~20 ppm to ~30 ppm.

3.6. The effect of weather conditions

Fig. 4. CO2ff variation from 2013 to 2014. The sites with a CO2ff decrease and increase from 2013 to 2014 are shown in blue and red, respectively.

Wind speed and wind direction have a strong influence on CO2transport and diffusion, which may be reflected in spatial CO2ffvariations. The average wind speed during April to September in Xi’an City (Xi’an Jinghe National Meteorological Station, No. 57131) in 2013 and 2014 was 2.66 m s-1and 2.54 m s-1, respectively, with typically low winds of about the same magnitude. Figure 5 shows wind rose diagrams for April to September in 2013 and 2014. The wind differences show an increase in southwesterly winds, and a decrease in north-northeasterly winds in 2014, as compared to 2013. There are some industrial parks in the southwest Xi’an urban area, including the large Xi’an Hi-Tech Industries Development Zone. Emissions from this zone could be carried to urban areas by southwesterly winds (Guo et al.,2014). CO2ffvalues of most sites near the west and south Bypass Highway did increase from 2013 to 2014, possibly due to more frequent southwesterly winds.

4. Conclusion and perspectives

The spatial distribution of CO2ffindicated by plant Δ14C measurements in the central Xi'an urban district in the April to September of 2013 and 2014 is presented in this paper. Three characteristics in our observed period based on the above results and discussion are as follows. First, the year-to-year variation of CO2fffrom different sites was significant. Second, there was no obvious difference in average CO2ffbetween the three districts divided by the Ring Road,

2nd Ring Road and the Bypass Highway. Third, the northeast corner of the study area featured distinctly lower CO2ffvalues than the rest of the sites studied. These spatial and temporal variations were influenced by emission sources and weather conditions. Vehicle exhaust emissions and residential emissions appeared to control the spatial differences.Weather conditions (wind direction in particular) also influenced regional temporal CO2ffvariations.

Our results show high spatial and temporal CO2ffvariations in Xi’an. Implicit in these results is the need for high spatial resolution, and long-term CO2ffmonitoring. To characterize CO2ffspatial distributions in urban areas, plant samples are economical and convenient. To obtain reliable results, there are some recommendations when adopting this method: (a) sampling sites should be chosen carefully, and over a large area, with sites distant from CO2emission sources being suitable; (b) the plants should grow in an open environment; and (c) widespread plants with a known growth period are preferable. Such a program would support timely carbon emission reduction measures and efficient policies to cope with future change.

Acknowledgments. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and Dr. George S. BURR for their helpful comments. This work was jointly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. NSFC41730108, 41773141,41573136, and 41991250), National Research Program for Key Issues in Air Pollution Control (Grant No. DQGG0105-02), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDA23010302), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (Grant No.2016360) and the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (Program No. 2019JCW-20).

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences2020年6期

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences2020年6期

- Advances in Atmospheric Sciences的其它文章

- Estimate of Hydrofluorocarbon Emissions for 2012-16 in the Yangtze River Delta, China

- Comparison of Ozone Fluxes over a Maize Field Measured with Gradient Methods and the Eddy Covariance Technique

- Deriving Temporal and Vertical Distributions of Methane in Xianghe Using Ground-based Fourier Transform Infrared and Gas-analyzer Measurements

- Direct Observations of Atmospheric Transport and Stratosphere-Troposphere Exchange from High-Precision Carbon Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide Profile Measurements

- An Observing System Simulation Experiment to Assess the Potential Impact of a Virtual Mobile Communication Tower-based Observation Network on Weather Forecasting Accuracy in China. Part 1: Weather Stations with a Typical Mobile Tower Height of 40 m

- On the Epochal Variability in the Frequency of Cyclones during the Pre-Onset and Onset Phases of the Monsoon over the North Indian Ocean