Cytapheresis for pyoderma gangrenosum associated with inflammatory bowel disease: A review of current status

Kentaro Tominaga, Kenya Kamimura, Hiroki Sato, Masayoshi Ko, Yuzo Kawata, Takeshi Mizusawa,Junji Yokoyama, Shuji Terai

Kentaro Tominaga, Kenya Kamimura, Hiroki Sato, Masayoshi Ko, Yuzo Kawata, Takeshi Mizusawa, Junji Yokoyama, Shuji Terai, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Niigata University, Niigata 951-8510, Japan

Abstract

Key words: Granulocytapheresis; Leucocytapheresis; Cytapheresis; Inflammatory bowel diseases; Pyoderma gangrenosum; Complications

INTRODUCTION

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), an inflammatory disease, is one of the neutrophilic dermatoses[1]. It is clinically characterized by painful skin ulcerations with erythematous and undermined borders, and histologically by the presence of neutrophilic infiltrates in the dermis[1,2]. It can present in several variants to a variety of health professionals and may not always be easily recognized. The annual incidence of PG is estimated at 3-10 per million persons[1], and is mostly associated with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease. Other association include rheumatoid arthritis (RA), seronegative arthritis, myelodysplastic syndrome, multiple myeloma, polycythemia vera, paraproteinemia, and leukemia[2].

Treatment of PG usually may include high-dose glucocorticoids (GC), dapsone,minocycline, methotrexate (MTX), cyclosporine (CsA), mycophenolate mofetil,intravenous immunoglobulin, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, and surgical options, usually colectomy[2,3]. Alternatively, granulocytapheresis (GCAP)/granulocyte and monocyte apheresis (GMA), and leucocytapheresis (LCAP) are therapeutic strategies of extracorporeal immunomodulation that can selectively remove activated leukocytes from the peripheral blood[4-6]. Kanekuraet al[7]reported the efficacy of GCAP/GMA for the first time in 2002 and this was supported by a report of LCAP in PG in 2003[8]. In 2017, Russoet al[9]firstly reported the efficacy of GCAP/GMA on PG other than the reports from Japan. For evaluating the efficacy of cytapheresis in PG treatment, we performed a literature review including all the case reports of PG associated with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) treated by cytapheresis, since 2002. We believe that the information summarized in this minireview will help the management of patients with PG and perhaps result in more formal trials of this novel therapy.

LITERATURE ANALYSIS

A literature search was conducted using PubMed, Ovid, and Ichushi provided by the Japan Medical Abstract Society, with the terms “cytapheresis”, “GMA”, “GCAP”, or“LCAP,” and “pyoderma gangrenosum” to extract the studies published in the last 20 years. The studies written in English and Japanese from relevant publications were selected. We have summarized the information on demographics, clinical symptoms,treatments, and the clinical courses from articles, including 22 case reports in Tables 1 and 2.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The annual incidence of PG is estimated to be approximately 3-10 patients per million persons and it usually affects patients of ages 20-50 years, and females more commonly than males. Infants and adolescents account for only 4% of the cases[10]. The etiology and mechanisms causing PG is unknown; however, 50%-70% of cases are associated with other diseases, such as IBD, arthritis, and lymphoproliferative disorders. PG is believed to involve abnormal immune responses and, possibly,vasculitis[11]. IBD is the most common comorbidity in PG, and PG constitutes approximately 1%-3% of the extraintestinal manifestations in patients with IBD[12,13].To verify the effect of cytapheresis on PG in IBD patients treated with GCAP/GMA,and LCAP[7-9,14-37]especially with IBD, we summarized 22 reported cases[8,14-17,20-29,31-37]and our case of PG (Table 1). the average age was 39.6 years (range, 19-73) and the ratio of males to females was 8:15 (Table 1) similar to the previous reports[1].

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of cases treated with cytapheresis

CLINICAL COURSE

Symptoms

The clinical course is unpredictable; it may not correlate with IBD activity and may even precede a diagnosis of IBD. PG most commonly affects the lower legs; however,PG at other sites of the body have been reported as well, including the breast, hand,trunk, head and neck, and peristomal skin. Overall, 25% of patients with PG have confirmed lesions on the head and neck[38,39]. We found that the clinical symptoms of PG were seen in all 23 cases and included the following distribution of the skin lesions: most of cases showed PG in lower limbs, followed by upper limbs, trunk,head and neck, buttocks, and site of postoperative wound (Table 1)[8,14-17,20-29,31-37]. Lower limb lesions were the most common lesions in these patients. The size of the skin lesions varied from 4 cm × 2 cm to 11 cm × 12 cm in diameter. PG is a painful and unsightly dermatologic disorder with the potential to significantly decrease a patient’s quality of life (QOL).

Treatments

A variety of drugs have been used to treat PG, including high-dose GC, dapsone,minocycline, MTX, CsA, mycophenolate mofetil, intravenous immunoglobulin, andTNF-alpha inhibitors[2,3]. The first-line of treatment for PG includes oral corticosteroids. In patients who do not respond, TNF-alpha inhibitors constitute the second-line of treatment[40]. Cytapheresis (GCAP/GMA and LCAP) has also been reported to be effective in PG for those cases refracted to GC. However, due to the small number of patients treated with cytapheresis and the unknown etiology, there is no established protocol of cytapheresis for PG. The clinical courses of case reports have been summarized in Table 2. Among the 23 cases, GC was used for 19 cases, CsA for 4 cases, diamino diphenyl sulfone for 1 case, salazosulfapyridine for 8 cases, 5-aminosalicylic acid for 6 cases, MTX for 2 cases, cyclophosphamide for 1 case,potassium iodide (PI) in 2 cases, and FK506 in 1 case, however, none of these 23 cases showed therapeutic effect on the ulcers[8,14-17,20-29,31-37].

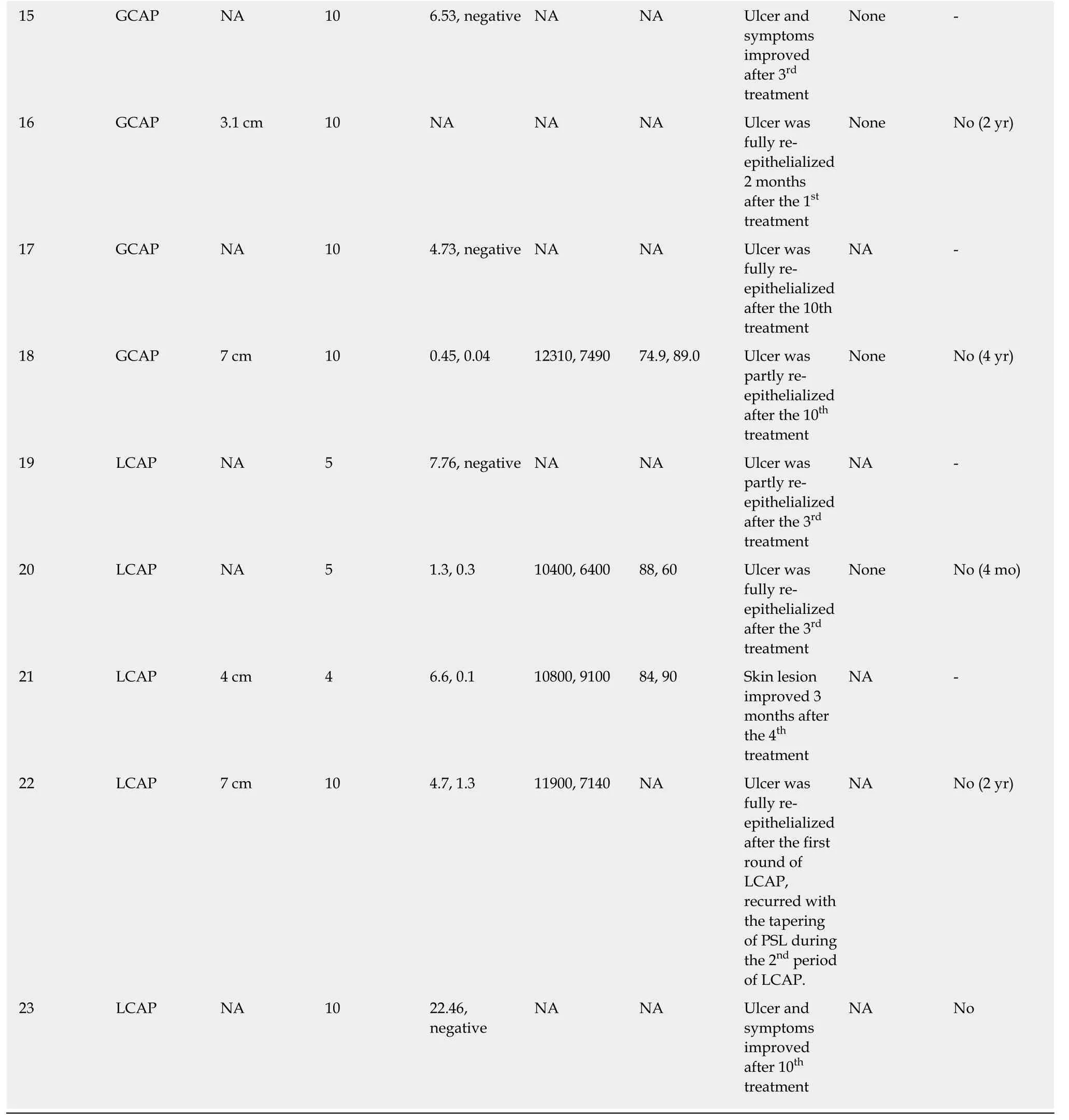

Table 2 Clinical course of the cases

GCAP: Granulocytapheresis; LCAP: Leukocytapheresis; CRP: C-reactive protein; WBC: White blood cell; NA: Data not available

CYTOPHERESIS

The 23 cases of cytapheresis included 18 cases of GCAP/GMA and 5 cases of LCAP(Tables 1 and 2)[8,14-17,20-29,31-37].

GCAP/GMA

GCAP/GMA is an extracorporeal apheresis technique in which a specialized column(Adacolumn, Japan Immunoresearch Laboratories, Takasaki, Japan) selectively traps activated granulocytes and monocytes/macrophages from the peripheral blood[41]. It was initially approved for the treatment of UC because it traps activated granulocytes[42,43]. Furthermore, it has been used in the treatment of several inflammatory diseases because neutrophils are crucial in their pathogeneses. A recent report demonstrated that the serum levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-alpha were markedly reduced by GCAP/GMA along with downregulation of L-selectin and the chemokine receptor CXCR3[41]. GCAP/GMA has also been reported to be effective in other disorders that are attributable to activated neutrophils, including PG. To prove this phenomenon,clinical trials of GCAP/GMA in the treatment of various skin diseases such as psoriasis, RA, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sweet’s disease, and PG are underway[18]. The effect of the treatment was various in each case and the change of serum CRP levels between pre- and post-treatment was investigated (Table 2). There were no reports of major side effects; headache was reported as a side effect in only one case. In 4 of 23 cases (17%), recurrence was observed and in three of those cases,complete cure was not achieved during the recurrence. The reasons for the recurrence may involve the discontinuous of treatment before the confirmation of the complete healing of the ulcer.

LCAP

LCAP is performed using a column designed to remove leukocyte contributing the inflammation, which is related to the activity of PG and UC[6]. The column is an extracorporeal perfusion type white blood cell apheresis unit. The column, Cellsorba(Asahi Kasei Medical, Tokyo, Japan), is composed of a filter within a filter, each composed of non-woven polyethylene terephthalate fabric, with both filters wound into a cylindrical shape and sealed with polyurethane. There were no reported adverse effects of LCAP, such as nausea, vomiting, and liver dysfunction, or recurrence of the lesions during the therapy[37]. The removal rate of activated granulocytes is 2-3 times that with GCAP/GMA. Furthermore, LCAP also has the ability to remove activated platelets, which irritate the granulocytes and release reactivated oxygen species[4]. We believe that LCAP may be a valuable tool in treating intractable PG in patients without lymphocytopenia and thrombocytopenia, however,due to the shortage of materials, it will not be able to be performed in Japan soon.

DISCUSSION

In terms of efficacy of cytapheresis, both GCAP/GMA and LCAP were effective treating PG that was resistant to steroids and other treatments. The ulcers of the lower extremities in PG result in gait disorders and significantly reduce QOL. In some cases,improvements in QOL have been reported following cytapheresis[24,26]. The frequency of LCAP in treating PG is less than that required with GCAP/GMA. Furthermore, the recurrence rate in LCAP is lower than that in GCAP/GMA. There were no reports of adverse side effects in both therapies; however, the number of cases is still small and further evaluations are necessary. The methods, advantages, and disadvantages of both GCAP/GMA and LCAP have been summarized in Table 3[4-6,37]. Both,GCAP/GMA and LCAP have a direct immunosuppressive effect by removing the activated leukocytes involved in the pathogenesis, an indirect anti-inflammatory action via complement activity, and result in functional improvements of regulatory T-cells. The main difference, however, is that LCAP has a high removal rate of not only granulocytes but also lymphocytes and activated platelets (Table 3). There were 4 cases of recurrences following several months after GCAP/GMA therapy[14,24,26,28]. On the other hand, LCAP was effective in all cases and there was no case of recurrence.Therefore, the therapeutic effect of LCAP in PG is presumed to be better. LCAP is considered to be more effective because the inflamed mucous membranes in UC with a long duration of illness are mainly elicited by the lymphocytes. Additionally, in cases of UC with deep and widespread ulcers, it has been reported that active platelets occlude and inhibit tissue regeneration[44]. Furthermore, in the peripheral blood of patients with RA and UC, microparticles derived from activated platelets increase and indirectly induce the release of chemokines and cytokines, which are important factors that cause thrombosis and inflammation[45]. By removing these platelets and microparticles, LCAP can prevent microvascular occlusion, promote tissue regeneration and epithelialization, and suppress cytokine-related inflammation[46]. Although the mechanism of cytapheresis in the treatment of PG is unknown, it has recently been reported that both neutrophils, on whose surface adhesion molecules such as Mac-1[19]and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 are expressed[47], and circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-8 and granulocyte colony stimulating-factor decrease following GCAP/GMA therapy.Recently, Nomuraet al[48]demonstrated in their retrospective study that cytapheresis was effective not only for inducing remission for UC itself but also for extra-intestinal dermal lesions of PG and erythema nodosum suggesting the efficacy of cytapheresis therapy for UC. The development of biologics for IBD will contribute to improve the various symptoms including PG, and therefore the further assessment and the accumulation of the cases are essential.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, for the cases of PG showing resistance to GC or other conventional therapies, cytapheresis with either GCAP/GMA or LCAP has the potential to be an effective and safe therapeutic option. It is clear; however, additional cases,information, and well-designed prospective clinical trials are necessary to develop the evidences to be one of the standardized therapies. From this point, our mini-review summarizing the cases of PG treated with cytapheresis will help physicians to understand the cytapheresis and treat cases with PG.

Table 3 Summary of cytapheresis

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年11期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年11期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Tumor circulome in the liquid biopsies for digestive tract cancer diagnosis and prognosis

- Isoflavones and inflammatory bowel disease

- Altered physiology of mesenchymal stem cells in the pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

- Association between liver targeted antiviral therapy in colorectal cancer and survival benefits: An appraisal

- Peroral endoscopic myotomy for management of gastrointestinal motility disorder

- Clinical prediction of complicated appendicitis: A case-control study utilizing logistic regression