人物访谈

Camouflage House

510 House

1、两位生活背景截然不同:一个来自芝加哥,一个来自德国柏林。是什么时候,又是怎样决定开始这种创造性伙伴关系的?

我们是在大学里读研究生的时候认识的,很快就成为了朋友,因为我们发现各自对建筑的看法很相似。虽然文化背景不同,但我们有着非常兼容的设计议程,并且都在探索解决类似建筑问题的答案。毕业后,我们都在其他建筑师事务所工作,但很快我们就意识到只有完全掌控自己的工作,才能创造出我们所感兴趣的建筑。于是,我们在2003 年创办了自己的工作室。多年来,我们开发了一种非常高效的方式来一起设计,相比较语言交流,我们更喜欢通过学习模型和草图来相互交流想法。

2、如今当代建筑似乎沉迷于美学奇观和算法造型,在这样一个时代,你们的作品以其形式上的简洁,概念上的清晰,以及与自然环境和谐的融合而脱颖而出。你们的设计过程是如何促进这一点的?

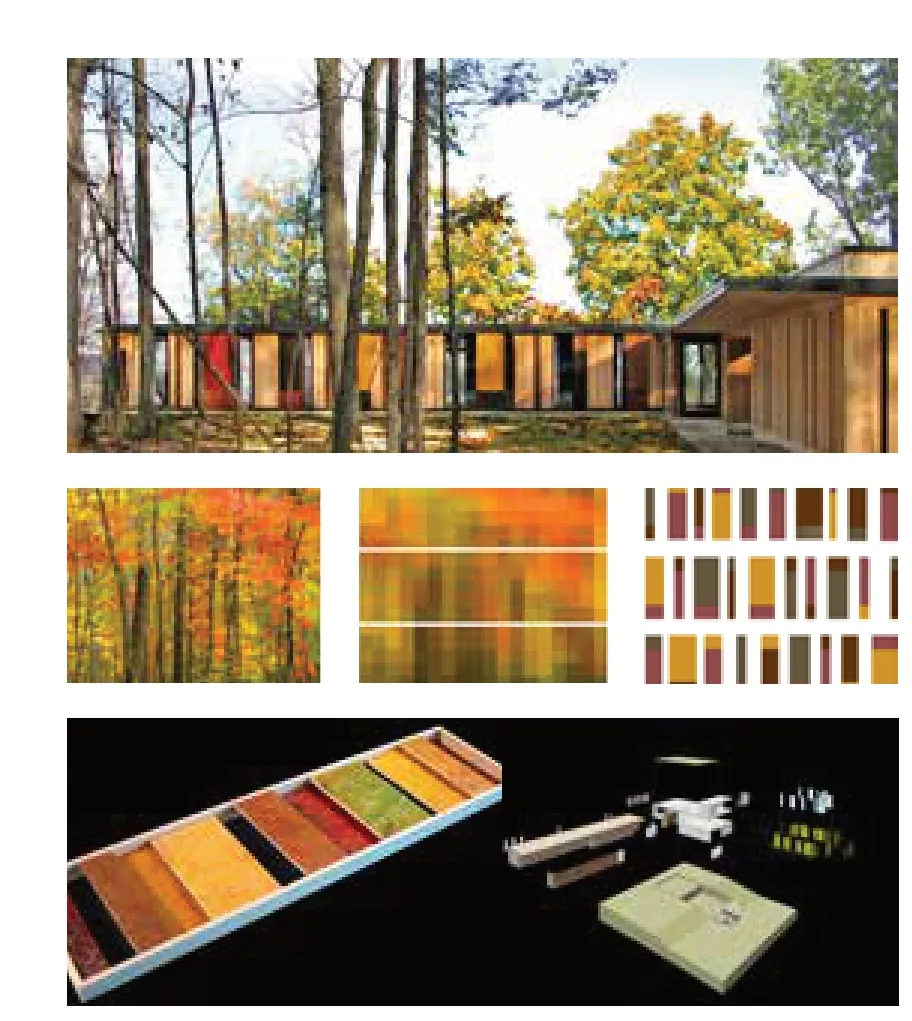

我们对现在建筑高峰的激烈竞争并不感兴趣,这种竞争通常只会留下表明自己在专业上高人一等的无用纪念碑,不是对真正的设计创新感兴趣。我们觉得这种建筑屈服于标志性建筑物的首要地位,充满了普遍性和随意性。相反,我们总是在自己的实践中寻找一种更微妙的方法;前提是找到安静和精致的建筑方案,这一点是不容妥协的。从第一个项目“迷彩屋”开始,我们就专注于不同的文脉概念,所有这些概念都以一个原则问题为指导:我们可以设计出这样一个建筑吗?它不是一个孤立的、自我参照的物体,它的形式和物质性能够得到发展,最终整个外观独立于它所在的这片土地。换句话说,我们试图在乡村和城市文脉中识别一个特定地点的特殊性,促进建筑设计的有意义的演变,从而使它成为文脉中直接的,似乎不可避免的一部分,传达对一个地点的归属感,甚至是历史感——但所有这些都不会屈服于字面上的模仿或落入任何风格的陷阱。

3、既然提到了文脉因素,那么你们的作品是否符合肯尼斯·弗兰普顿(Kenneth Frampton)“批判性区域主义”理念?

不,我们对文脉的理解与“批判性区域主义”有着本质区别,后者可以说是通过一个更广阔的地理视角来看待文脉。相反,我们感兴趣的是在一个特定地点的尺度上,那些细微的、有时甚至是隐藏的品质,甚至是特质——这些东西帮助我们建立一种建筑叙事,以一种安静、有意义和特定地点的方式为我们的设计过程提供信息。正因为如此,最初的实地考察在我们设计的概念演变中起到了重要的作用。正是在那些考察中,我们才第一次面对和体验未来项目的环境,仔细倾听那些存在的东西。然后,我们基本上将我们个人的感官体验和对现场气氛的记忆进行提取,并将它们转化为抽象的建筑操作调色板,指导我们完成整个项目开发,从方案设计到具体建筑细节的工艺。(注:本段附带的图片可能是Blatz Bottle Doors 的图片)。所有这些都给我们的建筑注入了某种氛围,这种氛围的灵感来自于我们主观的、有目的的选择性回忆。或者,用海德格尔的术语,“感念(Andenken)”,特定地点最显著的特征,包括物理、历史、气氛和社会特征。同时,我们对离开可构造性和功能逻辑的领域没有兴趣,因为我们的最终目标是创建一个能达到预期目的的物理建筑。

4、Topo 住宅是一个似乎能体现你对文脉态度的项目,它似乎与其所在土地完全融合,受到了广泛好评。这个设计的灵感来源于什么?

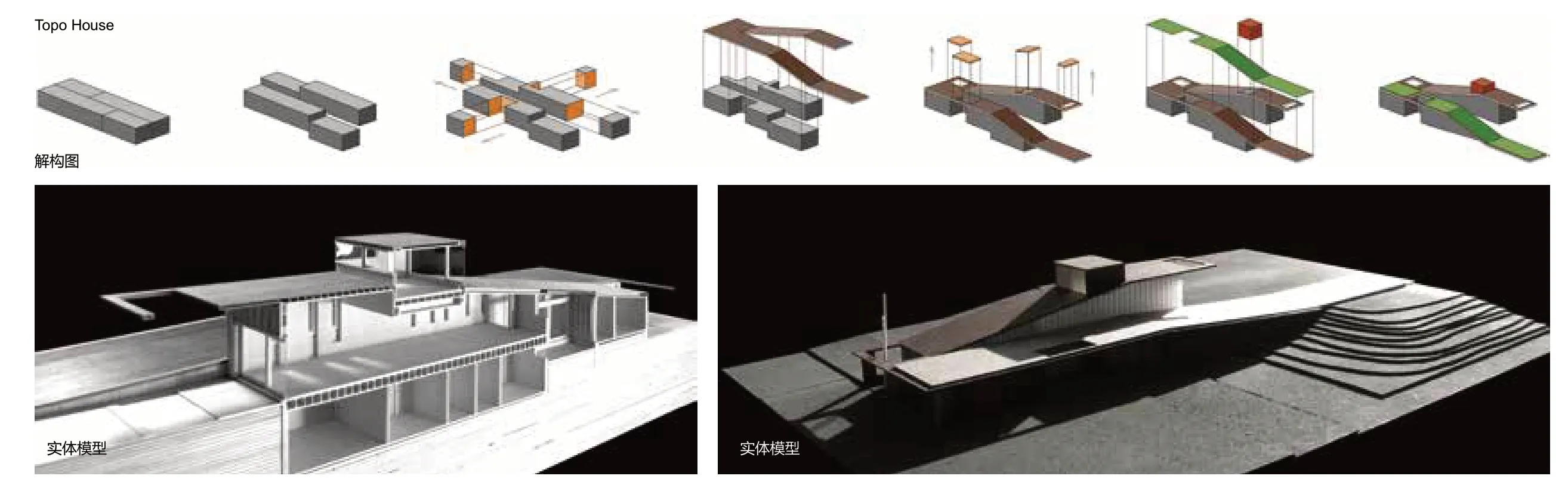

多年来,我们尝试了不同的策略,让建筑物融入周围的环境。以前面提到的“迷彩屋”为例,其解决方案是将文脉抽象地投射到建筑体积上——建筑表皮基本上起到了伪装的作用,以隐藏森林中房屋的存在。对于Topo 住宅,我们以不同的方式处理了文脉问题,根据场地独特的地形规划建筑的所有形式;它变成了我们实践中的一个关键项目,通过它,我们可以在三维上探索文脉反应。该项目位于威斯康星州北部,座落在一片开阔的大草原上,镶嵌在该地区柔软起伏的山丘和紧密的山涧的自然景观中。我们开始设计探索,把环境中的体验注入一个概念模型里,使一系列折叠平面能够相互移动。这个模型激发了建筑聚集的灵感。两条平行的钢筋与一个从地面升起的铜屋顶平面连接在一起,其平缓的斜坡与周围的地形相呼应。这是一座低调的建筑,一座沉静,阴沉的建筑,尽可能地不显眼地融入风景中。

5、2010 年的OS 住宅被认为是美国第一批真正可持续发展的私人住宅之一。它和Topo 住宅最大的区别是什么?

很明显,这两个项目之间存在一些形式上的差异。我们各自的设计探索由完全不同的背景参数指导,差异由此产生:一个是一所深植于乡村环境中的房子,另一个则坐落在一个历史悠久的城市街区。但更重要的一点,OS 住宅最初是考虑环境和高水平技术因素。该项目于2010 年完工,那时技术已经取得了巨大的进步,但在当时,它依然是美国最先进、最可持续发展的住宅建筑之一。同时,文脉因素对于OS 住宅也起到了重要的作用;在其他当代建筑的衬托下,这座建筑看起来非常现代。它修复了城市肌理,毫无疑问,其多色立面框架迎合了该地区维多利亚时代住宅的色彩。

Belay MKE

Topo House

6、你们的作品包括一系列珍贵的小森林休息处,像线性小屋或堆叠小屋。这些美丽的建筑明显是现代建筑,但极赋古老、富有地域特色的建筑风格。能讲一下传统和创新是如何影响你的木屋设计过程的吗?

实际上,我们相信“传统”和“现代”这样的标签非常武断,这在建筑语言中完全没有意义。建筑一直是历史延续中的一部分,认为当代建筑完全新式才有意义的设定是目光短浅且幼稚的。没有哪一个建筑不受先前建筑的影响,不管是好是坏,都要受到过去文化的影响。重要的是要认识到,即使是在建筑现代主义出现时美学范式上的转变,也只不过是几个世纪以来的建筑链排列的有序总结。以密斯·凡·德罗的建筑为例,他的建筑当然是完全现代化的,但同时也两百年前弗里德里希·辛克尔的古典主义作品的影响。从这种意义上说,我们认为,传统和创新并不是对立的,它们不可避免地存在交集,事实上是相互影响的。因此,我们很欣赏乡村乡土建筑,它们的时代特征给我们的设计以敏锐的直觉和明确、惊人的解决方案,这启发了我们的木屋设计。通过仔细研究中西部木屋建筑类型的历史,以及弄清楚它们的建筑结构和组织结构,我们学到了很多东西——细节的约束,对气候条件做出的调整,以及和田园环境的联系。在确定了一些历史先例主导的设计的基本规则之后,我们在更具现代元素的文脉下重新阐释了它们,重新根据具体的场地条件和场地特征适当地布置组成部分,如景观、现有植被,以期能够更广泛地回应现代生活方式的要求和期望。

7、您的事务所和设计流程是如何受到当前学界趋势影响的?反过来说,您目前的项目和流程是如何指导正在发展的学术课程的重组和发展的?

我们都是威斯康星大学的教授,经常被邀请到这里以及欧洲的其他建筑学校教授设计课程。教学允许我们以一种更加严格和不妥协的态度,更深入地探讨建筑问题,这是我们在日常实践中可能做不到的。我们在大学的高级设计工作室往往是密集的实验室,通常专注于我们自己工作中令人感兴趣的具体建筑问题,例如紧凑的住房,新兴的城市建筑形式,或者更细致的层面上的问题,如材料处理和建筑表皮。我们试图超越纯粹的学术思辨,用以实践为基础的参数来调节概念上的开放式主题,我们相信这种方法带来的好处是相互的。我们为自己的研究引入了初始的知识框架,它引导着我们与

学生进行为期一个学期的创造性对话,这让我们对建筑的可能性充满信心和希望。自然,可持续性的问题已经不可逆转地在过去十年中改变了学术界,环境责任已经成为我们学生真正关心的问题;他们希望确保自己对建筑的贡献不会出现前几代人的错误。这些学生现在开始加入工作大军,并正在迅速加速建筑向更有生态意识的专业方向的转变,造福所有人。

8、约翰森-施马林建筑事务所未来将面临哪些挑战?

随着这些年来委托业务和规模的稳步增长,现在我们的项目遍布美国各地,最大的挑战是管理我们事务所的业务增长,并在密尔沃基的办公室保持高度协作的设计文化,这对我们的创作过程至关重要。事务所现在有十位建筑师,我们都在一个巨大的开放空间里工作,这个空间鼓励所有人相互进行持续、内容丰富的对话,这种对话可以培养一种优秀文化。对于我们来说,即使项目不可避免地变得更加复杂,也要能够在事务所中保持这种富于创造性的亲密感和思维的严谨,这至关重要。

9、你们对中国建筑的印象是什么?会接受在中国设计建筑的机会吗?

尽管中国的很多建筑作品都出自西方建筑师之手,我们也认识许多优秀的中国建筑师,关注他们的作品并且非常欣赏。很明显,我们正在见证年轻而自信的一代中国建筑师的出现,他们创造出了非常有趣并在美学上具有革命性的作品。这是一项我们极为尊重和特别喜爱的工作,因为它同样展示了我们在自己的工作中所追求的真实一面。在某些案例中,我们看到在美国或欧洲会因为更高的劳动力成本和更严格的建筑规范而无法实现的建筑设计。考虑到所有这些问题,对于我们来说,在中国开展一个项目是极其有吸引力的,并且可以测试一下在目前的有利条件下,如何能够以在美国不可能实现的方式推动我们的设计事项。也许更重要的是,这将是一个在根本不同的文化文脉下,重新应用我们适配文脉的设计流程的机会。

10、你对在中国学习建筑学的学生有什么建议吗?

我们给中国学生的建议与我们给自己学生的建议相似:走出去看看世界,体验现实生活中的建筑,而不仅仅是通过电脑屏幕或书籍来了解建筑。如果有机会去国外学习,就好好利用这个机会——这将挑战你自己的先入为主的观念,同时能够拓宽你对世界各地建筑丰富元素的理解。

1.You both come from very different backgrounds: one of you is originally from Chicago, the other from Berlin, Germany.When and how did you decide to start your creative partnership?

We met as graduate students in college and immediately bonded because we noticed great similarities in the way we approached architecture. Despite our different cultural upbringings, we shared very compatible design agendas and were exploring answers to similar architectural problems. After graduation, we both worked for other architects but soon realized that we needed to be in full control of our work in order to create the kind of architecture that we were interested in, so we started our own office in 2003. Over the years, we have developed a very efficient way to design together, relying less on words than on study models and sketches to communicate our ideas to one another.

2.At a time when much of contemporary architecture seems obsessed with aesthetic spectacles and algorithmic form-making, your work stands out for its formal simplicity, conceptual clarity, and an ability to quietly harmonize or blend in with the natural environment. How does your design process facilitate that?

We have never had any interest in today’s breathless race for architectural superlatives that usually leaves behind vain monuments speaking more of professional one-upmanship than a sincere interest in genuine design innovation.We feel that this kind of architecture merely subjugates itself to the primacy of the iconic, thus making it completely generic and arbitrary. We have instead always been looking for a more subtle approach in our own practice; our premise is to find architectural solutions that are uncompromisingly quiet and restrained. Starting with our very first project, the Camouflage House, we have focused on different notions of contextuality, all guided by one principle question: How can we design a building so that it does not just sit on the land as a solitary, self-referential object but instead develops its form, its materiality, and ultimately its entire appearance out of the land it occupies? In other words, we try to identify the particularities of a specific site,in both rural and urban environments, to help inform the meaningful evolution of a building design so that it can become an immediate and seemingly inevitable part of its context, to convey a sense of belonging to a site, perhaps even a sense of history– but all that without succumbing to literal mimicry or falling into any stylistic traps.

3.When you mention contextuality, would it be fair to position your work within the trajectory of Kenneth Frampton’s concept of “Critical Regionalism”?

No, our understanding of contextuality is fundamentally different from “Critical Regionalism,” which arguably looks at context through a geographically broader lens. Instead, what we are interested in are the subtle, sometimes even hidden,qualities, maybe even idiosyncrasies, at the scale of a particular site — something that helps us develop an architectural narrative that informs our design process in a quiet and meaningful and site-specific way. Because of that, our initial site visits play an instrumental role in the conceptual evolution of our designs.It is during those visits that we first encounter and experience the surroundings of a future project andcarefully listen to what exists. We thenbasically metabolize our very personal sensory experiences and atmospheric memories of the locale and translate them into an abstract palette of architectural operations that guide us through the entire project development, from schematic design all the way to the

crafting of specific construction details.(note: an image that might accompany this paragraph could be of the Blatz Bottle Doors).All this imbues our buildings with a certain aura that is inspired by our subjective and purposefully selective recollection, or, to use a Heideggerian term, Andenken, of a particular site’s most striking characteristics, both physical, historic, atmosphericand social. At the same time, we have no interest in ever leaving the realm of constructability and functional logic, because our ultimate objective is to create a physical building that works for its desired purpose.

4.One project that seems to exemplifyyour attitude toward context is the Topo House, which appears to literally merge with the land it occupies and has received wide critical acclaim. What inspired its design?

Over the years, we have experimented with various strategies to allow our buildings to virtually disappear within their respective surroundings.In the case of the previously mentionedCamouflage House, the solution was an abstracted projection of context onto the building volume – the building skin basically functioned as camouflageto hide the presence of house in the forest.For the Topo House we approached the issue of contextuality differently and developed the entire form of the building out of the site’s distinct topography; it became a pivotal project in our practice because it allowed us to explore a contextual response in three dimensions.The project is located innorthern Wisconsin and sits on a wide-open prairie field,embedded in the region’s natural landscape of softly rolling hills and tight ravines.We started our design exploration by turning our experience of moving through this landscape into a conceptual modelfeaturing a series of folding planes shifted againstone another. That model inspired the massing of the building, two parallel bars tied together with a copper roof plane that rises out of the ground, its gentle slope echoing the surrounding topography. It’s a building with a low profile, a calm,somber building that sits in the landscape as inconspicuously as possible.

5.The OS House from 2010 is considered one of the first truly sustainable private residences in the United States. What are the biggest differences between this house and The Topo House?

There are obviously a number of formal differences between the two projects, which are the result of the fundamentally dissimilar contextual parameters that guided our respective design explorations for each: one is a house embedded in a deeply rural environment, the other sitting in a historic urban neighborhood. But perhaps more importantly, the OS House was primarily conceived as a case study for an environmentallyresponsible and technically high-performing urban residence.The project was completed in 2010, and technology has made tremendous strides since, but at the time, it was one of the most progressive and sustainable residential buildings in America.At the same time, contextuality played an important role for the OS House as well; as contemporary as it looks in the context of its historic neighbors, the building repairs the urban fabric, and its polychromatic façade frames are an unapologetic nod to the cheerful polychrome of the area’s Victorian homes.

6.Your body of work includes a series of precious little forest retreats, like the Linear Cabinor the Stacked Cabin.These beautiful buildings are decisively modern and yet seem to be steeped in the regional architecture of the past.Can you describe how both tradition and innovation influenced your design process for the cabins?

We actually believe that labels like “traditional” and “modern” are arbitrary terms and entirely meaningless in architectural discourse. Architecture has always been part of a historic continuum, and the premise that contemporary architecture needs to be entirely novel in order to be relevant is short-sighted and naïve.There simply is no architecture that is not informed by precedents or influenced, for better or worse, by cultural preconceptions. It’s important to realize that even the aesthetic paradigm shift at the emergence of architectural modernism was nothing but the logical conclusion to a chain of architectural permutations that spanned centuries.Take, for example,Mies van der Rohe’s buildings, which were of course radically modern but simultaneously deeply indebted to the classicist work of Friedrich Schinkel from two hundred years prior.In that sense, we believe that tradition and innovation are not antithetical but inevitably intertwined and, in fact, reciprocal.We therefore havea sincere appreciation of rural vernacular architecture and the often intuitive and astonishingly unambiguoussolutions it offered to the design problems of its time, and it is what inspired our designs for the cabins. We learned a lot fromcarefully studying the historic typology of Midwestern cabin compounds and the structural and organizational clarity with which they were constructed – the restraint of their details, their response to climatic conditions, their relationship to their bucolic settings.After identifying some elemental rules that governed the design of the historic precedents, we re-interpreted them within the context of a more contemporary vocabulary, re-arranging the component pieces in a way that would allow us to respond appropriately to specific site conditions and site features like views and existing vegetation, and more general, to the demands and expectations of a modern lifestyle.

7.How is your office and design process being influenced by current trends in academia? ln turn, how are current projects and processes guiding the ongoing reformulation and development of academic curricula?

We are both Professors at the University of Wisconsin and frequently invited to teach design classes at other architecture schools here and in Europe. Teaching allows us to explore architectural issues in more depth, and at a somewhat more rigorous and uncompromising level, than is sometimes possible in our day-to-day practice. Our advanced-level design studios at the university tend to be intense laboratories that focus on the specific architectural problems that we are interested in our own work, such as compact housing, emerging forms of urbanism, or, at a more detailed level, material manipulations and building skins. We try to transcend pure academic speculation by tempering conceptually open-ended themes with praxis-based parameters, and we believe the benefits of this approach are reciprocal.We introduce the initial intellectual framework for our investigations,which guides a semester-long creative dialogue with our students that usually leaves us invigorated and hopeful for architecture’s possibilities.Naturally, the issue of sustainability has irreversibly changed academia over the last decade or so, and environmental responsibility has become a genuine concern of our students; they want to ensure that their contributions to the built environment will not repeat the mistakes of previous generations. These students are now starting to enter the workforce and are rapidly accelerating the transformation of architecture into a more ecologically aware profession, to the benefit of all of us.

8.What are the challenges that Johnsen Schmaling Architects will face in the future?

With the steady increase in the number and size of commissions over the years,and with much of our projects now spread all across America, our biggest challenge is to manage the growth of our office and maintainthe highly collaborative design culture in our Milwaukee-based office that is so critical to our creative process.We are currently ten architects, and we are all working in a large open space that encourages a continuous and fertile dialogue between all of, a dialogue that fosters a well-calibrated culture of excellence. It will be critical for us to be able to preserve that kind of creative intimacy and intellectual rigor in studio, even as our projects become inevitably more complex.

9.What is your impression of Chinese architecture? Would you embrace an opportunity to design a building in China?

Even though a lot of the published architecture in China is by Western architects, we know a number of terrific Chinese architects whose work we follow and very much admire. It’s clear that we are witnessing the emergence of a young and confident generation of Chinese architects who produce extraordinarily interesting and aesthetically revolutionary work. It is work for which we have tremendous respect and a special affinity because it exhibits the same sense of authenticity that we are pursuing in our own work. In some cases, we have seen architectural experiments that would be prohibitive in America or Europe because of higher labor costs and more restrictive building codes. Considering all this, it would be immensely interesting for us to work on a project in China and test how those favorable conditions we have observed could propel our design agenda in ways that would be impossible in America. Perhaps more importantly, it would be an opportunity to re-apply our design process of contextual metabolism in a fundamentally different cultural context.

10.Do you have any suggestions for students who are studying architecture in China?

Our advice would be similar to the one we have for our own students: Go get out and see the world to experience architecture in real life, not just through the mediating lens of a computer screen or book. If you have the opportunity to study abroad, take advantage of it – it willchallenge your own preconceptions and broaden your understanding of the rich DNA that architecture around the world can offer.

Topo House