当代景观设计的现时危机与未来挑战:从特质出发的设计途径

著:(西班牙)米盖尔·维达·普拉 译:边思敏 校:王勤

当代景观设计的发展趋势,正在与社会和地域之间关系的复杂性发生冲突。由于社会、经济、地理或者宗教等原因,这些关系在集体和个体层面都变得更为复杂。故而,原来用以划分与自然相关的空间的传统分类方式(从自然保护区到花园),对于建立一个能够涵盖所有映射自然的空间的景观设计研究框架已不再适用。

所有景观都是其内在特质(identity)的表象。同时,特质也可以用来区分和识别不同景观。因此,以下的设计途径就是合乎逻辑的:即从那些定义了不同景观当代性(contemporaneity)的特质出发构建当代景观。

从特质出发的当代景观设计项目为分析这些特质是如何在历史长河中留存下来提供了机会,同时也会反映出这些特质的表现方式,比如实体景观的形态发生了怎样的变化。

笔者阐释了以下几个包含于当代景观中的特质:记忆(memory)、天堂(paradise)、阿卡狄亚(arcadia)、控制(control)、凝思(contemplation)、仪式(liturgy)、 城市性(urbanity)、知识(knowledge)、过程(the processes)、崇高(the sublime)、持续突现性(permanent emergency)[1-2]。

1 记忆

营造纪念性景观的目的是以物质性景观来回顾过去发生的某一独特事件的特质。本节主要探讨超越精神(transcendent)是如何透过纪念物呈现于当代景观之中的。

越战纪念碑(Vietnam Veterans Memorial)位于华盛顿,1982年由林璎(Maya Lin)设计;911国家纪念碑和博物馆(National September 11 Memorial & Museum)位于纽约,2011年由迈克尔·阿拉德(Michael Arad)和彼得·沃克(Peter Walker)设计。2个项目的共同特征在于抽象性和虚无性,但是,这样的特性对于林璎来说是可以置身其中的,而迈克尔·阿拉德则更强调不可企及的感受。这2个空间都没有还原具象,却唤起了人们对过往的记忆。

越战纪念碑这一项目反映了在景观设计中表达一种真实特征的困难性。在林璎的设计中,记忆的表达超越了图像,并且被这样一种由空间营造出来的氛围唤起:游客被公园地表裂开的硬地“伤口”引入内部的土地,象征了死亡的体验。黑色的花岗岩墙面上镌刻了58 272名阵亡美国军人的名字,抛光的花岗岩材质映射出来访者的身影,仿佛那些消逝在越战中的军人在人们的记忆中浮现。

正如林璎的自述:“我更喜欢把设计当作与每个人的单独对话,无论它具有多强的公共性,或者会有多少人在场。”

911国家纪念碑和博物馆的设计无意呈现双子塔遭遇恐怖袭击之前的特质,不想复原作为纽约地标的存在感,也不影射袭击事件本身,而是希望唤起对于所有以上事件后果的反思:某种东西的缺失。设计者通过2个设置在原地基位置的深水池物化了这种缺失特质的表达。水不断地从水池周缘涌入,然后消失在中央的深井之中,留下始终缺失的空间(图1)。

1 记忆。911国家纪念碑和博物馆。一种难以接近的虚空,水流向内部不断倾泻,又消失于黑暗中,让人联想到流逝、离去和缺失Memory. National September 11 Memorial & Museum.Inaccessible emptiness. Inside water flows constantly and disappears in the darkness. This evokes flowing, going away, absence

2 天堂

在一些项目设计中,表达天堂特质的目的是营建一个被周遭环境包围,但又异化于周围的,格外友善的环境。它们是人们想从不完美的或者充满敌意的环境逃往一个热情友好环境的归宿。“天堂”景观同样可以由外部自然要素构成,但更偏重于凭借这些要素自身的条件特征来构建文化氛围或是宏大场景。不论就哪种情况来说,生动、微妙或是极端的感受都是非常重要的。“天堂”景观为人们提供了通常被外部环境否定的知觉和舒适体验,并且在社会和文化秩序上唤起了一种新的范式。

然而“天堂”感受的唤起取决于每个人对于天堂的定义。从这个层面上来讲,巴黎迪士尼公园(Disneyland Paris)和冒险港之类的主题公园,就可以被称为21世纪的“天堂”景观。它们提供了一个封闭的梦幻世界,这是对由大众传媒构建的、远离日常生活的虚构故事(fiction)的物质化体现。

秘密花园(意大利语:Il Segretto Giardino,图2)和冒险港主题公园(Port Aventura)诠释了“天堂”的当代含义,而阿尔罕布拉宫(格拉纳达,穆罕默德·伊布·纳斯尔,1238—1492)则以物质景观表达了“天堂”的历史内涵。

2 天堂。秘密花园。在这里,天堂是指相背于城市喧嚣,而嵌入巴塞罗那扩展区的一个封闭性花园Paradise. Il Segretto Giardino. Here paradise is a closed garden opposed to the city and fitted in the Eixample(“Enlargement”) in Barcelona

以上3个案例的共同目标,就是建立一个与敌对而平庸的外界现实环境相反的友善的闭合空间。

位于巴塞罗那的秘密花园,1991年由胡安·若格(Joan Roig)、恩瑞克·巴特约(Enric Batlle)和奥尔加·塔拉索(Olga Tarraso)设计。该设计是埃斯科萨多公园(Excorxador Park)设计竞赛的第一名,面积为4 hm2。场地被一道墙体限定并形成了一个封闭的绿洲,一系列如诗如画的场景以“水”元素串联。主要入口处的瀑布灵感来自蒂沃利花园(Tivoli Garden)的椭圆形喷泉(Oval Fountain),可以起到阻隔外部视线的作用。

杜莎默林娱乐集团的冒险港主题公园(1995年)位于西班牙塔拉戈纳省比拉塞卡和萨洛市(Vilaseca, Salou),与其他主题公园类似,是“天堂”的一种当代版本,它不是被完美化的大自然,而是一个可以体验神话和异域世界的聚会地。换句话说,人们可以在这儿获得不属于日常生活的体验。原初意义上的天堂往往倾向于内省,当代版天堂则是一种逃脱和某种形式的疏离。冒险港被认为是欧洲第六大游乐园。杜莎默林娱乐集团起初只计划了5个“目的地”—地中海、波利尼西亚、中国、墨西哥和远西。每个目的地都有自己的故事,但还在不断加入新的游乐设施。在5个由板材搭建的具有主题场景的“天堂”中,游客可以体验到极致的眩晕感和速度感,而主要的游乐设施也提升了商业街的人流量[3]。

3 阿卡狄亚

正如雅各布·桑纳扎罗(Jacopo Sannazaro)在1504年的同名小说中所描述的,阿卡狄亚指那些自然与乡村和谐相融之所的风景。不同于天堂(天堂中无人劳作)和乌托邦(关于如何组织完美社会的构想),阿卡狄亚由于给出了一种在大尺度下兼顾美与功能的范例,而对当下的景观设计意义非凡。建立当代的阿卡狄亚,可以为营造城市、乡村和混合型景观提供新的类型学参考,它在自然、功能,偶尔也包括艺术等领域之间产生了协同效应(synergies)。

这一类的案例包括位于美国新墨西哥州马格莱纳镇达圣奥古斯汀山谷的巨构阵列景观(Very Large Array)和拉维莱特公园(法语:Parc de la Villette)。

尽管以上两例在规模和用途等方面存在差异,但它们在大自然和人类活动之间的关系处理上都具有互补性,即通过人为参与来构建场所的特质。

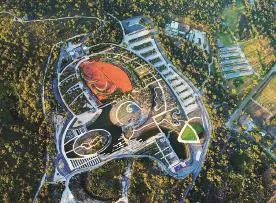

位于新墨西哥州马格达莱纳镇的美国国家射电天文台的巨构阵列景观,1972—1980年由美国联邦基金研究与发展中心创建。这一深入圣奥古斯汀山谷的项目因为采用了Y字形阵列,在人为与自然之间呈现出了更强烈的对比关系。27台口径25 m的天线组成的射电望远镜阵列沿着3个分支排布,轨迹长达50 km,每个分支上布有9座看上去仿佛在丈量大地的巨型白色雕塑(图3)。

3 阿卡狄亚。巨构阵列景观。美国联邦基金研究与发展中心的这27座天线组成的巨构阵列是沙漠景观文化的象征,创造了一种技术化的、当代的阿卡狄亚Arcadia. VLA. NRAO. The 27 antennas in the National Radio Astronomy Observatory culturalize the desert landscape and create a technological and contemporary arcadia

拉维莱特公园位于巴黎,1983年由伯纳德·屈米(Bernard Tschumi)设计。屈米在拉维莱特公园设计中运用了阿卡狄亚的哲学,并致敬了利西茨基(Lissitzky)①和苏联建构主义(Constructivist Architecture)。在100 m×100 m的网格体系中,屈米设置了一系列匪夷所思的、介于建筑和雕塑之间的混合构筑物(folie),象征着人类知识(knowledge)和大自然在场地中彼此交融[4-6]。

4 控制

控制的特性隐含于所有试图基于权力(power)、代表性(representativeness)、秩序(order)、领土原因(territorial reasons)等的叙事来构建或定义一个地域的人为干预之中。无论不可见因素随着历史进程如何更迭,透视法(perspectives)始终是这类景观的基本机制。从某种意义上来讲,透视法造就了17世纪路易十四时期的绝对主义景观(Absolutist Landscape)、18世纪皮尔·查尔斯·朗方(Pierre Charles L'Enfant)设计的华盛顿国家广场(National Mall)和20世纪的麦克米兰规划(McMillan Plan)。而透过持续至21世纪的塞尔吉·蓬图瓦兹主轴(Axe Majeur de Cergy-Pontoise)项目,依然可以看到远在50 km之外的巴黎和其周边城镇连绵的景象。

然而除了古典透视法之外,还有其他定义场域的方式,它们将场域和艺术、某种用途或者某种人设的形式(form)联系起来。艺术对于场域的定性体现在克里斯托(Christo)和珍妮·克劳德(Jeanne-Claude)创作的《飞篱》(Runnin Fence)项目纯粹的美学痕迹中,以及《雨伞》(Umbrellas)项目所呈现的类似元素的有序或随机重复中。

塞尔吉·蓬图瓦兹主轴位于法国塞尔吉·蓬图瓦兹(Cergy-Pontoise),1980年至今仍在持续进行修建,由达尼·卡拉万(Dani Karavan)设计。主轴指向远处以埃菲尔铁塔为高潮的广阔视野,这一设计的目的是在巴黎市区和里卡多·波菲尔(Ricardo Bo fill)设计的卫星城之间建立一种身份认同感和共享城市性(shared urbanity)。不同于巴洛克风格的建造形制,设计沿轴线置入了具有雕塑或主题序列的、富于变换的断面(图4)[7]。

4 控制。塞尔吉·蓬图瓦兹主轴。被重新诠释的巴洛克视角将巴黎拉德芳斯中心商务区(the Defense)的都市特征,带入了一座尚缺乏特质的新城Control. The Axe Majeur of Cergy-Pontoise. The reinterpreted Baroque perspective brings the urbanity of Paris, the Defense, to a city that still has no identity

位于福特山谷(Valley Ford)索诺玛的《飞篱》,1976年由克里斯托和珍妮·克劳德设计。《飞篱》是一条全长约40 km,穿越了59位私有领主土地的折线。艺术家希望构筑一条纯粹为审美而生的线性轨迹,不考虑其他功能,也不是用自然线条来描绘几何景观。他们声称:“我们想要构建的不仅仅是一条穿越疆域的藩篱,而是一种由于人类的存在和象征性的干预而产生的新景观。”

位于美国克恩县第戎牧场(Tejon Ranch)和日本茨城县佐藤河谷(Sato river valley,Ibaraki)的《雨伞》为美日合作项目,1991年由克里斯托和珍妮·克劳德设计。10月9日日出时分,分布在加州第戎牧场和茨城县佐藤河谷的3 100把雨伞同时撑开。设计的目的之一是突出2个疆域的差异性。在美国,这一艺术创作覆盖了25块私有领土,而在日本同样的面积则涉及495位土地所有者。这影响到了伞的分布密度—日本要比加州密得多。此外,日本的蓝色雨伞还象征着水源的丰沛,美国的黄色雨伞则指代沙漠的干旱。

5 凝思

东西方园林景观的巨大区别源于其对待自然的原始态度。在西方,创世纪的犹太基督教教义(“要生养众多,遍满地面,治理这地”)确立了其要控制自然的最初观念,这一点不论在英国式园林还是风景如画(picturesque)风格的园林景观中均无例外。几乎所有西方园林形式都是通过操控自然来创造新景观,不同之处则在于是否刻意强调控制的过程。

自人类纪元之初,中国文化中的儒教、道教和佛教就已经在思索决定着其神秘文化渊源的、人与自然关系的问题。与基督教的激进主义相比,上述三大宗教的哲学观,而非教义,孕育出了一种更为微妙的阐释途径。正如庄子所言:以自然之道,养自然之身。

常令人惊讶的是,当具有千年文化渊源的中国园林在与当下时代发生对话时,却呈现出一种四海皆准的普遍形式。

牛津词典对“contemplate”一词存在2种不同解释:“长时间地凝视”和“思考”。前者代表了其西方意义,而后者则反映了其东方意义。

上述2种意义存在于所有那些意图接近自然的景观之中,无论尺度大小,无不以一种感性的方式强调可以凝思的重点方面或者过程。其状态可以分为“开放式”(open)和“闭合式”(closed)。

5.1 开放式凝思

东方的开放式凝思提供了一种囊括视野高远的大尺度空间,以及天时或四季自然变化的感性经验。例如,颐和园(1271—1764年)就是通过具有相应功能的建筑空间营造了一种静态的、礼仪性的沉思体验,此外“知春亭”“排云殿”等的命名也暗示了其礼仪功能。

而在西方当代的开放式凝思空间中,观察者的态度具有更强的参与性,而这样的景观也可以从3个角度来欣赏:1)通过身体的运动引向对景观的动态观察,如瞭望塔项目(Observation Tower);2)激发观者的感官体验,如克里斯托弗·贝尼古(Chirstophe Benichou)在峰尖盒子(Tip-Box)中制造的眩晕感和不稳定感;3)树立景观中的地标。

探险营地(Camp Adventure)瞭望塔位于丹麦哈斯莱乌(Gisselfeld),2017年由EFFEKT建筑事务所设计。如前文所述,瞭望塔引入了盘旋向上的运动,通过转向轴线创造了动态观察自然的方式,使人们对景观的感知持续变化,在上升中获得启发。

位于圣路峰(Pic-Saint-Loup)的峰尖盒子,2017年由克里斯托弗·贝尼古设计。峰尖盒子体现了当代设计中的两大特征:地标(landmark)在景观中的作用以及感觉的融入,即以感性的方式连接观者和景观。

5.2 闭合式凝思

这类景观通过对自然的抽象唤起更具哲学意味和普遍性的特质,诸如龙安寺(Ryoanji,位于京都,1450年细川胜元设计)、加州剧本(California Scenario)和风中绘画(Drawing in the wind)。引人关注的实体景观成为观者和终极现实(final reality)之间的纽带。

加州剧本位于加利福尼亚州科斯塔梅萨(Costa Mesa, California),1980—1982 年由野口勇(Isamu Noguchi)设计。设计以盆景的方式将加州自然风貌整合在一个不到0.5 hm2的花园里,反映出东方文化的影响。同时又以极简主义的表现手法再现了南部地区前哥伦布文化时期的金字塔、河流和沟渠。

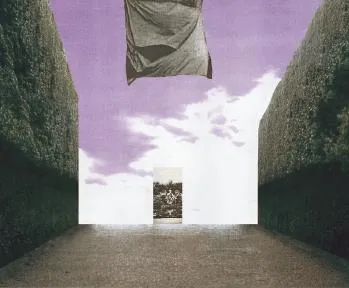

风中绘画位于巴塞罗那(Barcelona),2014年由米盖尔·维达(Miquel Vidal)设计。内庭院里的竹子和破碎大理石等自然元素象征着建筑创作过程,房子的创作概念写在玻璃上,手的动作表现了一种努力和追寻,竹子代表无用的杂想,庭院中央的小房子则意味着项目的终结(图5)。

5 闭合式凝思。风中绘画。凝视用“手”、破碎大理石、无用的竹子和原型房子构成的近景就是在发现建筑项目过程中的风景Close contemplation. Drawing in the wind. Contemplating the close landscape of the hands, the pieces of marble,the useless bamboos and the archetypical house is discovering the landscape of the architectural project

6 仪式

仪式空间。仪式是在宗教性或与之类似的公共机构中进行仪典活动的具体行为方式。仪式性体现在与超越(transcendent)特质有关的景观项目中。“移动”在这类景观之中至关重要,譬如进行的方式、轨迹、先后承接的序列、时间、节奏等。正是一个接一个的、与无形事物相关联的仪式进程,串起了其景观空间中的一条条路径。

紫禁城(1360—1424年,明成祖朱棣永乐年间敕造,阮安、蒯祥、蔡信主持营建)和天坛(1406—1420年,明成祖朱棣永乐年间敕造)是2处北京的历史标志性建筑群,承担着中国历史上2项最根本的礼仪功能。在这2个案例中,前者的朝圣对象是接近半人半神的皇帝,即天子的尘世途径;而后者则对应了祭天祈谷的仪式。对比紫禁城和天坛轴线之间的差异是一件非常有趣的事。

紫禁城依南北轴线布局,北至神武门,外延至景山,南至午门,外延至天安门广场。然而这条神秘的、隐喻性的轴线②从未被觉察,而是遵循着一种渐进的序列过程。造访者在其中逐渐接近一种非物质状态的、不可见的、半神圣的存在,这是一种神秘而深刻的文化体验(cultural experience)。

一道道宫城门,以及不同尺度、形制的建筑和过渡空间的存在,加上它们的命名引导,如太和门、太和殿、乾清宫、神武门等,层层强化了这种仪式性的个体经验。

天坛祭天祈谷的仪式决定了天坛的线性序列结构。主轴线始自祈年殿,终于寰丘坛。皇帝在祈年殿中和神明交流,而在寰丘坛上当众召唤众神庇护。衔接这两个线性空间的是在轴线约1/3处的皇穹宇和成贞门。以上所有都说明了行程的序列性,这是仪式过程的一种特定模式,而非任何视觉上的参照。

苏维埃战争纪念碑(The Soviet War Memorial)和采石场公墓(Fossar de la Pedrera)是2处现代的仪式空间,前者是柏林战役阵亡士兵的长眠之所,后者是遭遇法西斯主义迫害的受难者的安息之地。

位于柏林的特雷普托公园(Treptower Park)的苏维埃战争纪念碑,于二战后的1949年,由一支跨学科团队共同协作完成,团队成员包括建筑师雅科夫·贝洛波尔斯基(Yakov B. Belopolsky)、雕塑师叶根尼(Yevgueny V. Vuchetich)、画师亚历山大·戈尔彭科(Alexander A. Gorpenko)、工程师萨拉·瓦列里乌斯(Sarra S. Valerius)。这座非凡的战争纪念碑和军人公墓于1949年5月8日正式对公众开放,用于纪念在柏林战役(1945年4月16日—1945年5月2日)中阵亡的士兵。与紫禁城和天坛类似,访客需要遵循一个由外部到达公园中心墓地的渐进历程。首先,几条宽阔的道路将人们汇合到一片空地,其中放置着一尊3 m高的花岗岩雕像—《故乡》;接着,一条在两排桦树掩映下的林荫道引导人们通过左右两面红色花岗岩的巨型旗帜雕塑墙,进入场地的主要部分—战争公墓;尽管其后的路径很短,但诸如方向的变化、地面的倾斜、视线的引导以及森林对墓地范围的框定等微妙的控制手段,依旧很好地将最终的知觉体验引向对公墓的凝思。

采石场公墓,1985年由贝斯·加利(Beth Gali)设计。这是一处西班牙内战期间遭法西斯主义迫害的受难者的合葬墓地。项目利用了墓地所在的一个半围合的采石场进行改造,并引入了渐进的仪式性历程。入口起始于一个由回收路缘石铺就的陡坡,这是一种对生活的残酷和走向重生的双重隐喻;接下来,人们将穿过一片松柏林中刻着遇难者姓名的石柱列,最终到达纪念空间。跨过围合采石场的铺设带,就是已被填平的采石坑空间范围,而坑底便是埋葬着众多遇难者的所在。地面上经年累月的落石成为一种对突变(即死亡)的隐喻(图6)。

6 仪式空间。采石场公墓。路径终点是埋葬着众多遇难者的所在(加泰罗尼亚语称为Fossar),以庄严的“死亡之在场”作为终结,将旅程转换为葬礼的仪式进程Liturgical. The Fossar de la Pedrera. The real presence of death in a mass grave (Fossar in Catalan) at the solemn end of an initiatory journey transforms it into a funeral, that is,liturgical

7 城市性

7.1 城市公园

以1982年拉维莱特公园为标志,当代城市公园超越了自1871年摄政公园(Regent's Park)以来的自然疗愈模式(natural-hygienist model),开始将自然引入历史城市,以缓和工业革命带来的衰退状况。无论从设计的严格管控还是城市发展必不可少的功能复杂性出发,城市公园的构想一直以来都是城市发展的必要条件;而如果从用途和环境2个方面来考量,城市公园则可以被视为城市性的替代形式。当代城市公园是处于城市内部或边界的大片地表,它们被组织起来以构建补充城市活动的不同叙事。

米罗公园(Joan Miró Park)、过渡花园(The Park Gardens in Transition)、超级线性公园(Superkilen)和炮台公园(Parc del Turó de la Rovira)是对城市基底特质进行转化的几个典型案例。米罗公园采用了一种另类的叙事方式,过渡公园是城市乡村化的叙事,超级线性公园和炮台公园则是都市特质的反映。

米罗公园位于巴塞罗那,1983年由贝斯·加利、马吕斯·金塔纳(Marius Quintana)、摩西·加利戈(Moisés Gallego)设计。这是一个示范公园应该如何从被使用的角度出发进行规划的案例。公园由2部分组成:一片松林(地中海松,Pinus halepensis),它的有机肌理异化于塞尔达(Cerdá)③方格网规划;而另一个在不同尺度的网格空间内栽植华盛顿棕榈(Washingtonia filifera)的区域又不同于巴塞罗那周边老村庄那种更不规则的格局—这正是19世纪被并入城市的圣徒街区(Sants)的异质所在。公园的多样化空间布局源自能让如聚会、运动、节庆等多类活动者同时使用公园的设计意图。自然元素是对园内进行结构组织的有效工具,并使米罗公园成为不同于其周边环境城市性的一种变异(图7)。

7 城市性(公园)。米罗公园基于对周边几何城市肌理的一种变异结构,其景观形式与塞尔达扩展区的几何性构成了强烈对比Urbanity. Parks. Joan Miró Park is based on an alternative structure to the geometry of the city. This way a landscape trace is opposed to the geometry of the Eixample by Cerdá

过渡花园位于汉诺威(Hannover),2000年由卡梅尔·卢阿菲(Kamel Loua fi)设计。该项目的有趣之处在于它身处城市边缘的农业区,设计师通过最小干预的手段为农业景观注入品质感,并进一步唤起场地最初的非都市性特征。这不仅激发了人们规划城市边缘地带的兴趣,而且加强了毗邻城市的农业持久性。卢阿菲的设计理念是建立一片分布着趣味中心、建筑、观景点和艺术品等要素的农业结构保留地。最终,这个以农业景观为基础的项目,通过在城市中营造不同寻常的空间尺度为人们提供了一处凝思场所。

炮台公园位于巴塞罗那,2015年由伊玛·简萨纳(Imma Jansana)、孔奇塔·德拉维拉(Conchita de la Villa)、罗伯特·德·鲍乌(Robert de Paauw)设计。场地的突出特质在于其被不断复写(palimpsest)的印记:伊比利亚村庄、西班牙内战,以及1948—1990年间棚户区的残余。曾经承担过去公园功能的建筑、抵御法西斯空袭的防空炮基座所在的圆形炮台、已拆除的棚屋区留下的长方形地基和花池等记忆要素,共同定义了公园的最终形式。

超级线性公园位于哥本哈根,2016年由Topotek 1和BIG建筑事务所设计。项目融合了多元文化身份,与其说是自然的再现,不如说它是城市功能的补充,是不同背景的综合体。这个身处城市另类空间中的公园意在通过由广告和建筑元素演化而来的地标构筑物,成为能够体现不同身份共存于城市之中的设计范例。此外,将一种身份简化为一个广告图标的做法往往能够引起公园使用群体对于不同身份的真实感知的质疑。

7.2 城市广场

广场通常是城市历史的产物,因此依旧能够讲述城市的故事。由此引人深思那些在过去和当下对城市发展至关重要的非物质因素和人类活动。从这个意义上来看,当代广场设计可以将城市的场所记忆、其相应的无形意义,以及新功能需求和广场自身叙事性的、功能性的和象征性的特征相互联结起来。

在多数情况下,公共广场正是重要的城市机构或者标志性建筑的所在地,因此它们可以表达城市的特质。棕榈树广场(Palm Tree Square)和荣耀广场(Glòries Square)就分别呈现了广场的历史性特征和当代城市新特质。

棕榈树广场位于巴塞罗那,1982年由佩德罗·巴拉甘(Pedro Barragán)、理查德·塞拉(Richard Serra)设计。作为贝索斯社区(Besòs neighbourhood)一直以来的地标,场地中的加纳利海枣(Phoenix canariensis)为项目带来了叙事性。而塞拉的两片雕塑墙体则进一步加强了这种叙事特征,同时通过将广场中的动态游戏区域和其余部分分离开来而起到了组织使用功能的作用。

城市天蓬(Urban Canopy),又称荣耀广场,由Agence Ter和Ana Coello两家事务所联合设计。如果说上一个案例主要侧重反映场地的历史特质,这一设计则在表现基于新城市模式的未来性。设计理念是通过建立一个生态空间来孕育全新的、有号召力的城市中心。虽然塞尔达规划中早已设定了荣耀广场的核心地位,这一空间性质却从未被巩固。相反,这一节点仅仅被用作轨道交通和城市道路的中转枢纽,连接了格兰大道(Gran Via)、对角线大道(Diagonal)和子午线大道(Meridiana)。广场设计意在将一种新的、生态的、自给自足的特征融入城市,并且与巴塞罗那丰富的活动和功能,以及源自本地历史文化特质的场所记忆兼容。

设计包含了3个标高层:底层是道路和公共交通;零标高层是一个连接周边城市区域的大型步行空间;第3层是天蓬,一片包含了森林树冠的栖息空间,它遮蔽了已被转化为人行空间的道路,从而将城市和公园广场连接成一个整体。公园的主要结构基于节点—一个与城市中心功能相关的活动区域。其中的微观节点成为保护生物多样性的栖息地,宏观节点则包括了一个信息广场和一个自然广场。此外,广场中还沿雷格古灌溉渠(Rec Comtal)遗迹布置了一系列硬质、软质空间和湿地花园。

8 知识

知识性景观指那些以学术或科学标准来组织要素并传播知识的设计项目。植物园就是一种基于知识性的景观项目类别,尽管它们起初只是各类植物大集合的场地,但很快这种项目类型就被视为景观和建筑设计的综合。杰弗里·杰里科(Geoffrey Jellicoe)和苏珊·杰里科(Susan Jellicoe)在《图解人类景观》(The Landscape of Man)一书中,就将1546年建成的帕多瓦(Padova)奥尔托植物园(Orto Botanico)称作文艺复兴时期花园的标志性案例。

在某种程度上,21世纪建成的澳大利亚花园(The Australian Garden)与奥尔托植物园类似,都是为知识的传播赋予了一种美学维度。不同的是,奥尔托植物园运用了类建筑语言,而澳大利亚花园的设计语言则更接近艺术。

在乔维克护理中心植物园(Gjovik Care Centre Arboretum)中,萨米·林塔拉(Sami Rintala)和达古尔·埃格森(Dagur Eggertsson)将知识的传播联系到自然和人类冲突(例如年轻的移民群体)之间的相似性。

澳大利亚花园位于维多利亚,2013年由泰勒·库里蒂·勒思林(Taylor Cullity Lethlean)、保罗·汤普森(Paul Thompson)设计。项目处于克兰伯恩(Cranboune)的一座旧采石场中,设计以水体作为叙事手段,向来访者展示澳大利亚植被的多样性。其中的植被包含了从沙漠到湿地的众多原生物种。设计的目的是通过诸如节水花园、红沙花园、瞬息湖雕塑等体现出澳大利亚植物种群审美和情感潜质的艺术作品来唤起人们的关注(图8)。

8 知识。澳大利亚花园。花园的主体结构由水系控制,并象征着知识的传播。园中各类内容的感性组织赋予了景观以美学价值Knowledge. The Australian Garden. The transmission of knowledge, here the water cycle, is the structure of the project. The sensitive management of its contents builds its aesthetic landscape

乔维克护理中心植物园位于乔维克(Gjovik),2012年由萨米·林塔拉、达古尔·埃格森设计。植物园用于“容纳”那些通过适应气候而最终驻扎在挪威的外来物种。日本建筑师鸣川肇(Hajime Narukawa)将地球分解成了96个三角形,林塔拉和埃格森借用这一三角形概念来组织花园空间,搭建帮助“侨居者”适应气候环境的保护结构。这座花园毗邻接收少年移民的庇护所。

9 过程

技术过程性特质存在于以最终的实体景观表现其创造过程的项目中,而景观的建造过程又构成了项目的故事。在场地的原初特质难以被复原的多数情况下,设计会以技术性的过程作为起点,并赋予场地新的用途。

以下几种被研究的过程直接决定了景观的实体特征:挖掘/矿坑,堆积/填埋场。

堆积属于在原始景观中的突变事件,可以为新的活动类型提供支持并最终成为地标,拜斯比公园(Byxbee Park)和苏利亚盐渣场(Salt slag in Súria)可以作为这一类的案例。

矿坑类空间则更适于形成多少有些封闭的、与周边环境较为分隔的区域。这一思路加强了此类空间形成的工业化过程的特征,“ Líthica”④采石场(Project Líthica)景观改造项目正是如此。

拜斯比公园位于加利福尼亚州帕罗奥图(Palo Alto),1960年由哈格里夫斯事务所(Hargreaves Associates)设计。这是一个通过使用暗示废弃物的要素来彰显填埋场历史的案例。设计意图在于说明,即使场地以垃圾堆为基础,经过彼得·理查兹(Peter Richards)和迈克尔·奥本海默(Michael Oppenheimer)等大地艺术家的介入,也能创造美丽的景观。其场地美学基于与垃圾填埋场有关的形式再创造,例如卡车卸载形成的地形,以及表现渗滤液池塘演变过程的原木桩森林(The Pole Field)⑤等。

苏利亚盐渣场项目提案(The speculative proposals of Salt slag in Súria)是由米盖尔·维达(Miquel Vidal)1986年在巴塞罗那建筑学院(ETSAB)主持的课程设计,隶属于其负责的“功能性土地”(Functional land)研究课题,目标是呈现通过以日益普及的新技术与当下的时代相连,创造新美学景观的诸多可能性,因此所有的提案都遵循了既定的创作程序和技术要求。

“Líthica”采石场位于梅诺卡城(Ciutadella de Menorca),其景观改造自1994年至今仍在进行,由蕾蒂西亚·索劳(Laetitia Sauleau-Lara-,简名拉拉)等设计。驿站采石场(pedreres de s'Hostal)是一个将梅诺卡岛上老马雷斯砂岩采石场(“marés” quarries)转化为艺术空间的景观改造项目。设计基于形成采石场的工业过程遗迹或是能够唤起这一建造过程的意向来创造景观,例如何塞·布拉沃(José Bravo)设计的由场地内开采的3 000块石头组成的“矿物迷宫”(图9)[8]。

9 过程。“Líthica”采石场景观改造。用来获取砂岩的“技术”所定义的空间体量、几何形状和表面肌理恰恰反映了该项目本身的强烈特质The process. Project Lithica. The technique that is used to obtain the sandstone that defines the volumes, its geometry and its textures is the identity of the project itself

10 崇高

与采用极限技术创造的、融合了对绝对美的思考和对技术挑战的迷恋的景观项目相对应,这里提到的“崇高”,与埃德蒙·伯克(Edmund Burke)在《关于我们崇高与美观念之根源的哲学探讨》(To Philosophical Inquiryinto the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful,1756年)一书中提到的“崇高”概念十分接近。埃德蒙·伯克将“美”从崇高性中抽离出来,这直接影响了人们如何从极限技术出发看待技术性景观的问题。正如阿兰·罗杰(Alain Roger)所描述的:身处米约高架桥(Millau Viaduct)之上(in situ),或者(对大多数人而言)在联盟号飞船(Soyuz space station)中看到的宇宙景象(in visu),能够唤起人们的崇高感受。康德认为崇高感源于“那些绝对大的”,伯克则解释说,崇高感是“被控制的摄人心魄的恐惧”或是“没有危险的惊奇”。这正是笔者在波波里系列(Boboli series)中研究无形内容之表达方式的目的所在(图10)。

10 崇高。波波里。拼贴画展示了从艺术过渡到风景的多种途径,试图使用当下的语言方式来处理历史内容,并唤起观者的崇高感受The sublime. Boboli. The collage presents a multiple approach from art to the landscape. It is intended to evoke the sublime in the spectator by manipulating historic contents with a current language

试想一个人在云雾中通过343 m高的米约高架桥时,其浪漫体验无异于卡斯帕·大卫·弗里德里希(Caspar David Friedrich)《云海上的旅人》(Wanderer above the Sea of Fog)的画作中屹立山巅的主人公。至此,我们会惊讶地发现,18世纪的浪漫主义精神与21世纪的极限技术连成了一个闭环。

米约高架桥由建筑师诺曼·福斯特(Norman Foster)和工程师米歇尔·维洛格(Michel Virlogeux)合作完成,是目前世界上最高的斜拉桥,加之其纤细的造型设计,米约高架桥已成为A75高速公路沿途景观中一处独特的地标[9-10]。

11 持续突现性

在以上的景观设计途径中,笔者已经阐释了现代景观至今是如何从诠释历史主流特质出发而成形的。

此外,还需要将以下几个因素考虑在内:急速的技术革新所带来的根本性转变,知识的新视野、控制论、人工智能、虚拟现实等淹没人文主义的新浪潮,以及我们深陷其中的对地球资源的巨大消耗。它们给景观设计带来了前所未有的、持续不断的变化,曾经的那些古典“特质”已然不再适用。

这种持续的转变和全球化共同导致了各种新突现的特质,于是,所谓的持续突现性便在本身还处于混沌之中而无法被定义的杂交(hybridisation)或永久性突变(permanent mutation)的过程中产生,但它们所指向的景观设计却仍是一团乱麻,尚未得到完善的阐释。

杂交是指将各种相互对立或不同的元素(如个人的、地理的、种族的)之间关联融合为持续互惠的混合体。这种项目很难识别出能够作为设计起点的稳定特质,因此按照齐格蒙特·鲍曼(Zygmunt Bauman)⑥的观点,我们可以将其解读为“流动特质”(liquid identities)。

永久性突变可以被理解为“淡出淡入”,也就是说当前一帧图像渐渐淡去但尚未完全消失时,新一帧图像徐徐出现,它可能与前一帧图像有关,也可能无关。这种情况的不断发生,致使具有足够稳定性的特质不复存在,以至于社会大众不知该如何辨识其中的真实含义。更何况在上述情形中,由接触引起的不稳定性几乎是同步发生的。

发生这种新冲突的原因之一,在于几个世纪前泛灵论(animist)⑦的影响日渐式微导致景观中人文主义理念的匮乏。对我们而言,一个激动人心的挑战无疑是构建一种新的风景园林学,以赋予这些新兴特质具体形式,创造具有此类新特质的景观。在笔者看来,生态和环境内涵对景观来说固然重要,但过于简单化。尽管这些议题当下形成了某种趋势,但笔者不认为它们应占据风景园林领域核心,因为新的风景园林学应形成自身与所有当代现有学科相结合的混合体[11]。

注释(Notes):

① 译者注:埃尔·利西茨基,苏联艺术家、设计师、摄像师和建筑师。俄罗斯先锋派的重要代表人物,其作品对包豪斯和建构主义运动有很大影响。

② 译者注:其轴线并不是以连续透视的形式出现,相对于勒诺特那种穿透的、“空”的轴线而言,紫禁城的轴线是暗示性的。

③ 译者注:现代城市规划的奠基人之一,是巴塞罗那扩展区的规划师,该区域的规划布局深刻影响了现代巴塞罗那城市的整体生长。

④ 译者注:“Líthica”协会是由法国籍雕塑家和建筑师Laetitia Sauleau(简称Lara)于1994年成立的非营利文化协会,其目的是保护马雷斯地区采石场文化历史地貌免于消失。

⑤ 译者注:1991年彼得·理查兹大地艺术作品,72棵原木电线杆桩被布置成矩阵森林,随着时间的流逝,垃圾降解产生的局部沉降使某些木桩不再处于垂直状态,由此,艺术家实现了引人关注垃圾填埋场公园人造的和不稳定的性质的意图。

⑥ 译者注:波兰社会理论家、哲学家,在其关于“后现代主义”的讨论中,用“流动的”(liquid)和“固定的”(solid)对相关问题进行比喻性阐释。

⑦ 译者注:又称万物有灵论,发源于17世纪,认为天下万物皆有灵魂或自然精神,并对其他自然现象造成影响。

图片来源:

图1 © 欧仁妮·维达;图2 © Batlle & Roig事务所;图3 ©美国联邦基金研究与发展中心网站;图4 © Jean-Pierre Dalbéra;图 5、6、10 © 米盖尔·维达·普拉;图7 ©贝斯·加利;图8 © Taylor Cully Lethlean事务所官网项目配图;图9 © 让·皮埃尔·福凯。

Contemporary Landscaping:An Approach from Identity,the Present Crisis, the Future Challenge

An approach to the current tendencies of contemporary landscaping clashes with the complexity of the relations between society and territory. At the collective and at the individual level these have become more complex due to social, economic, geographical or religious reasons.Therefore the traditional categories that are used to classify the spaces of relation with nature (from natural reserves to gardens) are not useful to build a framework within which the totality of the spaces projected with nature can be studied.

Identity is inherent to all landscapes as these are its image. At the same time it distinguishes them and it identifies them. Consequently, this seems logical:the construction of the state of the contemporary landscape from the identities that define the different landscapes of contemporaneity.

The presentation of the projects of contemporary landscapes from their identities also offers the opportunity to analyze how these remain over the course of history. What changes is their expression, i.e. their physical landscape.

This text is structured from those identities that encompass contemporary landscaping:memory, paradise, arcadia, control, contemplation,liturgy, urbanity, knowledge, the processes, the sublime and the permanent emergency[1-2].

1 Memory

Memory. Landscapes of memory. Memorials are projects in which the objective of the physical landscape is to look back on the identity of a unique event that took place in the past. In this section we study how the transcendent is manifested in contemporary landscaping, mainly through memorials.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial by Maya Lin. Washington, 1982. National September 11 Memorial & Museum by Michael Arad and Peter Walker. New York, 2011. What they have in common is abstraction and emptiness but in Maya Lin they are accessible and in Michael Arad they are inaccessible. Both spaces evoke the past but without reductionist images.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial by Maya Lin.Washington, 1982. It illustrates the difficulty of transmitting real identity. The identity of memory in Lin's project is transmitted beyond the images and evoked by the atmosphere that the space creates:a wound on the surface of the park that drags the visitor into the inner part of the earth,which means the experience of death. On the black granite wall the names of the 58,272 fallen U.S. service members are inscribed. The polished granite reflects the image of the visitors, who are confused due to the memory of the veterans disappeared in Vietnam.

“I like to think about my work like creating a private conversation with each person regardless of how public it may be or how many people are present.” Maya Ying Lin.

National September 11 Memorial & Museum by Michael Arad and Peter Walker. New York,2011. The project does not refer to the identity before the attack on the Twin Towers. It does not refer to its presence as a landmark of the New York landscape. It does not refer to the attack itself.The memorial does evoke the consequence of all of that:absence. Michael Arad materializes that absence in two deep pools marking where the Twin Towers stood. The water rushes from the perimeter and disappears in a deep central well leaving the space absent from everything continuously (Fig. 1).

2 Paradises

Paradises. The identity of paradise is expressed in those projects whose objective is the creation of a friendly environment which is confined from its immediate environment and which is often contrasted with it. It is the escape from an imperfect or hostile context to a friendly and welcoming context. Paradises can be built with the same external natural elements but they are culturalized or constitute big scenographies with their own discourse. In both cases living subtle sensory sensations or extreme ones is important.Paradises offer the sensory sensations that the external environment denies in the order of perception and comfort and also in the social and cultural order evokes new paradigms.

However, the evocation of paradises varies depending on the idea of paradise that one has.In this sense the current theme parks such as Disneyland Paris or Port Aventura are the paradises of the 21st century as they are a closed dream world, the materialization offiction by mass media and far from everyday life.

Il Segretto Giardino and Port Aventuraare two examples that express the contemporary identity of “paradise” whereas the Alhambra in Granada,Mohammed Ibd Nasr. 1238—1492, shows a physical landscape of our past centuries (Fig. 2).

In these three projects the objective of creating a closed and friendly space in opposition to a hostile and common environment is present.

Il Segretto Giardino. Joan Roig, Enric Batlle and Olga Tarraso. Barcelona, 1991. It was the first runner-up prize in the competition for theEscorxadorPark. Its surface area is 4 hectares. It is delimited by a wall that closes an oasis, which is formed by a succession of picturesque scenes around an element of water that unites all of it. A waterfall in the main access, which is inspired in the Oval Fountain in the Tivoli Gardens, prevents from seeing outside the park.

Port Aventura Group Tussauds- Merlin Entertainment. Vilaseca, Salou (Tarragona), 1995.Like other theme parks this is a contemporary version of a paradise, not like perfected nature but like a meeting place where one can experience myths, the exotic. In other words, here one can experience what doesn't belong to every day life.Whereas original paradises lead to introspection contemporary paradises lead to escaping and to some kind of alienation. Port Aventura is regarded as the 6th best amusement park in Europe. The original project of the group Tussauds-Merlin Entertainment is structured on five “destinations”:Mediterrània, Polynesia, China, Mexico and the Far West. Each has its own story but new rides are added continuously. One can experience extreme sensations of vertigo and speed in archetypal settings made of cardboard in the 5 paradises that the theme park offers. The main rides foster mobility along the streets with shops[3].

3 Arcadia

Arcadia. Arcadias are the landscapes of those places where nature and the rural use of the place live in harmony as it is described in the eponymous novel by Jacopo Sannazaro in 1504. Arcadias are different from paradises (where work doesn't exist)and from utopia (which is a proposal of how to organize a perfect society). As a reference for the present landscapingarcadiais very important as it suggests the compatibility between beauty and function at a big scale. Building contemporary arcadias can be a reference for the creation of new topologies of urban, rural and mixed landscapes. An important aspect ofarcadiais that it generates synergies between nature, function and,occasionally, art.

Examples of this are the following:the landscape of Very Large Array in San Agustin Valley (Magdalena, Mexico) and the Parc de la Villette.

Although there is a difference in scales and in uses the two landscapes share a complementarity between nature and activity in such a way that what is anthropogenic participates in the construction of the identity of the place.

Very Large Array. National Radio Astronomy Observatory (Magdalena, Mexico). Federally Funded Research and Development Centre of the United States 1972—1980. In the project of San Agustin Valley there is more contrast in the relation between function and nature due to the incorporation of a Y-shaped array. The 27 white antennas are distributed along the three arms of a track which is 50 long. On each arm there are 9 antennas.They are like huge white sculptures that mark the landscape (Fig. 3).

The Parc de la Villette. Bernard Tschumi.Paris, 1983. In his project for theParc de laVillettein Paris Bernard Tschumi uses the philosophy ofarcadia. He pays tribute to Lissitzky and the constructivist architecture in the Soviet Union and he places afolie(a folly, which is a hybrid object between architecture and sculpture) on a grid of 100 m × 100 m. This way knowledge and nature are interrelated within the park[4-6].

4 Control

Control. The identity of control includes all those interventions that structure or give a sense to the territory from a narration which is based on intangibles such as power, representativeness, order and territorial reasons. It goes without saying that perspective has been and still is one of the most common mechanisms with this aim. Besides its intangibles have changed over the course of history.In this sense perspective structures the absolutist landscape under Louis XIV in the 17th century,the project of The National Mall in Washington by Pierre Charles L'Enfant in the 18th century and the McMillan Plan in the 20th century. In the 21st century in the project of Axe Majeur de Cergy-Pontoise a perspective of over 50 km connects Paris with the peripheral town visually.

However, apart from the classical perspective,other ways of defining a territory come up. These link the territory to art, to a use or to a form of exploitation. Art as an identifier of a territory exemplifies in the purely aesthetic trace of Running Fence or in the orderly or at random repetition of similar elements as it occurs in The Umbrellas Project, both by Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

The Axe Majeur of Cergy-Pontoise. Dani Karavan.Cergy-Pontoise, 1980—ongoing. The immense perspective that culminates at the distant Eiffel Tower aims at giving identity and shared urbanity between Paris and a satellite peripheral town that was designed by Ricardo Bofill. Mechanisms of construction are different from Baroque. Axial perspectives are inserted with changing sections that have sculptural or thematic sequences (Fig. 4)[7].

Running Fence. Christo and Jeanne-Claude.Valley Ford, Sonoma, 1976. Running Fence is a zigzagging line of about 40 km long that affected over 59 owners. In this project the authors propose the trace of a line whose only objective is generate beauty as opposed to the other functional or natural lines that draw the geometry of the landscape.The authors say:“we intend to build something else than just a fence that goes over the territory,we intend that human presence, that symbolized intervention, generates a new landscape.”

The Umbrellas. Joint Project for Japan and U.S.A. Corporation. Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Kern County, Tejon Ranch (U.S.A.) and Sato river valley,Ibaraki (Japan). 1991. In this project 3,100 umbrellas were distributed and open simultaneously in Tejon Ranch in California, U.S.A. and on the Sato river valley in the Prefecture of Ibaraki, Japan. This took place on October 9 at sunrise. One of the objectives was to highlight the difference of the territories. In U.S.A. the project affected 25 properties. With a similar extension in Japan 459 private landowners were added. That determined the density when it came to setting the umbrellas, which was more intense in Japan than in California. Besides, the blue umbrellas in Japan referred to the abundance of water and the yellow umbrellas in U.S.A. referred to the dryness of the desert.

5 Contemplation

Contemplation. Between West landscape and East landscape there is a big difference that is originated in the original attitude towards nature.In the West the Jewish Christian mandate of Genesis (“Be fruitful and multiply, fill the earth and subdue it”) establishes the first idea of landscaping in the West. It is the control of nature. Neither British landscape nor picturesque landscape are an exception. All Western forms manipulate nature to create new landscapes and the difference lies in highlighting or not the process of control.

Since the beginning of the millenary Chinese culture Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism have contemplated the relation between man and nature which defines their mystic root. The philosophical aspect rather than the dogmatic aspect of the three major religions fosters a more subtle approach than Christian radicalism. An example of this is what Zhuangzi recommends:wandering without worries and become one with “the Path” ( Tào ) when following nature.

It often comes as a surprise that Chinese landscaping looks beyond the seas when millenary identities in it claim a dialogue with contemporaneity.

In the Oxford dictionary there are different definitions for the word “contemplate”:“look thoughtfully for a long time at” and “think about”. The first definition would define Western contemplation and the second one would define Eastern contemplation.

The identity of contemplation of both refers to all those landscapes that are designed to approach nature, either at a big scale or at a small scale, in a sensitive way and underlining remarkable aspects of it or its processes. The contemplation can be open or closed.

5.1 The Open Contemplation

Eastern open contemplation offers the sensitive experience of big spaces with distant horizons and that of natural processes that take place in them along one day or along the different seasons. In the Summer Palace (1271—1764) a static and ceremonious contemplation takes place and it does so from an architectural space which is created with this aim. The names in it already indicate its functions:Zichun Pavilion, “Perceiving Spring”, Paiyun Gate, “The Hall of Dispelling Clouds”.

In Western contemporary open contemplation the observer's attitude is more participatory. This can be appreciated in three aspects. First, in the incorporation of movement that leads to a dynamic vision of the landscape such as in the Observation Tower. Second, it provokes sensory experiences such as vertigo and instability as it occurs in the Tip-Box by Christophe Benichou. And third, it is a landmark in the landscape.

Observation Tower. Architect Effekt.Camp adventure. Gisselfeld. Denmark, 2017. As mentioned above it incorporates the spiral upward movement. This way the contemplation of nature is created in a dynamic way by turning around an axis, which generates a constant change in the perception of the landscape. One has an initiatory sense in its ascent.

Tip-Box. Christophe Benichou. Pic-Saint-Loup, 2017. In Tip-Box the two characteristics of contemporary viewpoints are very present, that is, the role of landmarks in the landscape and the incorporation of sensations that, in a sensory way,link the observer with the landscape.

5.2 The Closed Contemplation

In the landscapes, which are based on the closed contemplation, such as Ryoan-ji (by Hosokawa Katsumoto. Kyoto, 1450), California Scenario or Drawing in the wind, the landscape is an abstraction of nature which likewise evokes another identity which is more philosophical and universal. The contemplated physical landscape is the bond between the observer and this final reality.

California Scenario by Isamu Noguchi. Costa Mesa. California, 1980—1982. In the garden by Isamu Noguchi the nature of California, in the form of bonsai, reflects the Eastern influence.Nature is integrated into the whole of a garden of less than 1/2 hectare. Minimalist interventions are described alongside:the pyramid, the river and the channel of the pre-Columbian culture of the southern State.

Drawing in the wind by Miquel Vidal.Barcelona, 2014. The natural elements of the inner garden, bamboos and crushed marble express the process of architectural creation. The house concept is written on the glass. The movement of the hand expresses the effort, the search. The bamboo represents useless ideas and the central house represents the end of the project (Fig. 5).

6 Liturgy

Liturgical spaces. Liturgy is how ceremonies are celebrated in a religion or in a similar institution.Liturgy expresses the landscape projects that are related to transcendent identities.

In these landscapes movement is very important as for the way it is carried out, the trace,the succession of the sequences, the time, the pace, etc. The ways are sequenced by a succession of rituals which are linked to another ritual that is related to the intangibles.

The Forbidden City (1360—1424). Emperor Zhu Di Yongle. Nyueng An, Kuai Xiang, Cai Xin.The Temple of Heaven (1406—1420). Emperor Zhu Di Yongle. These are the two historic landmarks in Beijing. They are two baseline historic identities as far as the incidence of liturgy in their design is concerned.

In the Chinese examples the first pilgrimage is the earthly approach to something that is semidivine, that is, to the emperor, son of the gods. In the second liturgy corresponds to the ceremony of Prayer for Good Harvests in The Temple of Heaven. It is interesting to see the difference between the axes of The Forbidden City and The Temple of Heaven.

The Forbidden City (1360—1424). Emperor Zhu Di Yongle. Nyueng An, Kuai Xiang, Cai Xin.The Forbidden City is organized on the North-South axis that, beyond the respective doors of the Divine Power to the North and the Meridian to the South, extends to Coal Hill and Tian'anmen Square. However, this mystical and allegorical axis is never perceived. It follows the sequences of an essentially initiatory journey. The visitor experiences an approach to something that is semidivine, an immaterial condition that cannot be visualized. All of it is lived as a mystical and deeply cultural experience.

The presence of gates, the different dimensions, the laying of the buildings, the spaces of transition as well as the names such as Gate of Supreme Harmony, Hall of Supreme Harmony,Palace of Heavenly Purity and The Gate of Divine Might reinforce this personal experience.

The Temple of Heaven (1406—1420).Emperor Zhu Di Yongle. It has a linear structure of sequences which are linked to the liturgy related to the Prayer for Good Harvests. The axis contains an origin and an end:The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests and The Circular Mound Altar. In The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests the emperor is in communion with the gods whereas in The Circular Mound Altar the emperor invokes the gods publicly. At a third of the axis that joins the two lineal spaces is The Imperial Vault of Heaven as well as the Temple's Gate from the Circular Mound Altar. All exemplify the sequential nature of the itinerary. They are patterns in the process of prayer but not visual references.

The Soviet War Memorial and el “Fossar de la Pedrera” are modern liturgic spaces. In the former the soldiers who died in the Battle of Berlin rest. In the latter the victims of Fascism rest.

The Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park. Berlin 1949. Yakov B. Belopolsky, architect.Yevgueny V. Vuchetich, sculptor. Alexander A.Gorpenko, painter. Sarra S. Valerius, engineer.The Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park was built by the interdisciplinary team after World War II. This extraordinary War Memorial and military cemetery commemorated the soldiers of the Red Army who died in the Battle of Berlin (1945-04-16—1945-05-02). It was officially dedicated to them on May 8, 1949. Like in The Forbidden City or in The Temple of Heaven the visitor follows an initiatory journey from outside to the cemetery that occupies the centre of the park. “Wide paths first take visitors into a clearing where they see a three-meter granite statue of ‘Mother Homeland'.A promenade flanked by weeping birches then leads past two huge stylized flags sculpted of red granite into the main section of the grounds,the actual war cemetery.” Although the route is smaller, in the control of the final perception to the contemplation of the common grave, subtle different mechanisms are used:the change of direction, the inclined plane, the perspective and the final framing of the forest that defines the cemetery.

The Fossar de la Pedrera, Beth Gali.1985. is the mass grave of the victims of Fascism during the Spanish Civil War. The project takes advantage of the quarry being semiclosed, where the burial area is, to introduce an initiatory liturgical journey. The way starts with a steep slope which is paved with recycled curbs. This represents a double reference to the harshness of life and to a second life. Later on one can access to the space of memory by going a set of columns among cypresses and pines.that are inscribed with the names of the victims who rest here. Beyond this threshold that closes the space of the quarry is the mass grave at the bottom of the quarry. The constant landslides become a metaphor of mutation, that is, death (Fig. 6).

7 Urbanity

7.1 Parks

With the Parc de la Villette in 1982 contemporary urban parks go beyond the naturalhygienist model that started with The Regent's Park in 1871, whose objective was bring nature to the historic city as a palliative of its degradation due to The Industrial Revolution. Urban parks, that have been conceived from regulatory rigidities in their design and also from functional complexities which are essential in urban development, can be regarded as alternative urbanities to the urbanity of the city when it comes to both the uses and environmental considerations. Contemporary parks are large surfaces inside the city or in their limits and they are organized to build different narratives that complement the urban activity.

Joan Miró Park, The Park Gardens in Transition, Superkilen and Parc del Turó de la Rovira are examples of different alternatives to the city. Joan Miró Park uses the alternative as a narrative of the project. The Park Gardens in Transition is the rural alternative to the city.Superkilen and Parc del Turó de la Rovira are reflections on urban identities.

Joan Miró Park by Beth Gali, Marius Quintana, Moisés Gallego. Barcelona, 1983. The park exemplifies the concern to plan the use of it correctly. It has two parts:a pine forest (Pinus halepensis), which is opposed to Cerdá's reticula,and a grid of spaces of different dimensions and internal treatment with palm trees (Washingtonia filifera), which is opposed to the more irregular structure of the old villages near Barcelona,that is, the neighbourhood of Sants, which was annexed to the city in the 19th century. Offering a diversity of spaces is due to a willingness to plan the simultaneous uses of the park:meeting points, sports, festivals, etc. Nature is a structuring tool in the park so that the identity of the park is the alternative to the urbanity of the city that surrounds it (Fig. 7).

The Park Gardens in Transition by Kamel Louafi, Hannover, 2000. This is a project of great interest, mainly because of the peri-urban agricultural areas. By introducing minimal interventions they give a quality to the agricultural landscapes and evoke their non urban origin and identity. This increases their interest in the planning of urban borders and reinforces the permanence of agriculture next to the city. Louafi's proposal for this project is the preservation of the agrarian structure where there are some centres of interest, architectures,viewpoints and works of art. The park, based on agrarian landscapes, allows the contemplation of spaces of an unusual scale in the city.

Parc del Turó de la Rovira by Imma Jansana,Conchita de la Villa and Robert de Paauw,Barcelona, 2015. The three identities are present in the palimpsest of the place:the remains of an Iberian village, the Spanish Civil War and the shantyism from 1948 to 1990. The shape of the park is defined by the architectures that had the functions of the park in the past as well as the circles that correspond to the anti-aircraft artillery bases, that defended the city from the fascist bombardments, and the reduced rectangles and pavements of the plants of the shanties that were saved from being demolished.

The Superkilen Park, designed by Topotek 1 &BIG Architects in Copenhagen in 2016, is a convergence of multicultural identities. Rather than a presence of nature the park is a functional complement of the city. It is a synthesis of different backgrounds. The park proposes, in an alternative space to the city, to be a reference to the different identities that coexist in the city through landmarks that derive from advertising or architectural elements. Reducing an identity to an advertising icon can generate doubts about the real perception of the different identities by the collectives who use the park.

7.2 Squares

The squares still keep the narrative of the city as it is often its historic memory. This contemplates both past and present intangibles and activities which were and are important in the development of the city. In this sense contemporary squares are projects that interrelate the narrative of the urban memory of the place, its corresponding intangibles and new functionalities with their own identity,which is narrative, functional and symbolic.

In most cases public squares express the identity of the city as institutional or representative buildings stand there. Plaça de la Palmera ( Palm Tree Square )and Plaça de les Glòries (Glòries Square) illustrate historic identities or identities of new forms of cities.

In the Plaça de la Palmera (Palm Tree Square)by Pedro Barragán and Richard Serra (Barcelona,1982).Phoenix canariensis, that had been a landmark in the Besòs neighbourhood for many years, brings the identity narrative to the project.This narrative is enhanced by two pieces of the work by Richard Serra, the Wall, that also organizes the use of the square by separating the dynamic play area from the rest area.

Urban Canopy, the project of the Plaça de les Glòries (Glòries Square) by Agence Ter and Ana Coello. If the previous project referred to a historic identity, its refers to a future identity which is based on a new model of a city. With this aim the project proposes to create an ecological space that welcomes a new and powerful centre.It establishes the centrality proposed by Cerdá for the Plaça de les Glòries ( Glòries Square ) which was never consolidated. Instead, it was used as a hub for rail connections and urban avenues:Gran Via, Diagonal and Meridiana. The design of the square proposes to incorporate a new, ecological and self-sustaining identity to the city. This identity is compatible with a wide range of activities and functions and also with the historic memories of the place inspired in the historical and local identities of Barcelona.

The project comprises three levels. At the lower level is road traffic and public transport.Zero level is a large pedestrian space that connects all urban fronts that limit the space. The third level is the canopy, the habitat that includes the space of the treetops in a forest and covers the former roads, that are pedestrian now, that connect the park to the city. The structure of the park is based on the node, an area of activity linked to a centre of interest. Micronodes are protected habitats that favor biodiversity. Macronodes are associated to a computing agora and to a natural agora. Besides there is a series of gardens:hard, soft and wet,following the trace of the Rec Comtal.

8 Knowledge

Knowledge. The landscape of knowledge is expressed by all those landscapes whose elements are arranged according to academic or scientific criteria to disseminate knowledge. Botanic gardens are an example of identity landscapes which are based on knowledge. Although at first they were a collection of plants their design was regarded as both landscaping and architecture very soon. In this sense the Orto Botanico in Padova (1546) is regarded as a landmark in the Renaissance gardens by Geoffrey and Susan Jellicoe inThe Landscape of Man.

To a certain extent, one can state that The Australian Garden in the 21st century develops the same process as Orto Botanico, that is, give an aesthetic dimension to the knowledge transmission.But it does so with another language which is as close to art asOrto Botanicowas to architecture.

In the Gjovik Care Centre Arboretum Sami Rintala and Dagur Eggertsson associate the dissemination of knowledge to similarities between nature and human conflicts such as the immigrant young people.

The Australian Garden,by Taylor Cullity Lethlean and Paul Thompson (Victoria, 2013) in an old quarry in Cranbourne, was structured with the water narrative to show the diversity of the Australian vegetation to visitors. The vegetation ranges from the origins in the desert to the wetlands. The aim is to raise awareness through works of art such as The Water Saving Garden,The Red Sand Garden, The Ephemeral Lake Sculpture that show the aesthetic and sensitive potential of the Australian flora (Fig. 8).

The Gjovik Care Centre Arboretum. Sami Rintala and Dagur Eggertsson. Gjovik, 2012.The arboretum is a project of a garden “to host”those foreign plant species which arrive in Norway so that they adapt to the climate. The work by Rintala and Eggertsson is related to the work by the Japanese architect Hajime Narukawa who decomposed the globe into 96 triangles whose proportions organize the garden and the necessary protection elements to ensure the acclimatisation of the “newly arrived”. There is a garden which surrounds an Asylum for immigrant young people.

9 The Processes

The processes. The technological process identity is one in which the final physical landscape expresses the process of creation. The process of the landscape construction creates the narrative of the project. In most cases the original identity cannot be recovered and the project takes the technological identity of the process like its starting point and it designs the new uses.

Here are the studied processes that determine the physical landscape of the identity directly. They are:deposit/land fills and extraction /quarries.

The deposit is an emergency in the original landscape, a unique support for new activities and finally a landmark. Examples of this are Byxbee Park and Salt slag in Súria.

On the other hand, quarries are spaces that tend to form areas more or less closed and often separated from their surroundings. This way they can reinforce the identity of their industrial process of formation as it happens in the Project Lithica.

Byxbee Park. Hargreaves Associates. Palo Alto. California, 1960. This is an example of those works where the narrative of the project makes the presence of the land fill explicit by using elements that refer to waste. In the Byxbee land fill the goal is the creation of a landscape that, assuming that its identity is based on a waste storage, is beautiful due to the incorporation of land artists such as Peter Richards and Michael Oppenheimer. Its aesthetics is based on the recreation of forms that are associated with waste, the topography of truck unloading, the Pole Field (the forest of cut logs),showing the evolution of leachate ponds, etc.

The speculative proposals of Salt slag in Súria,Miquel Vidal. ETSAB, 1986 were developed in the subject called “Functional land” coordinated by Miquel Vidal in the Architecture School of Barcelona, 1986. The goal is to show the chances to create new, aesthetic landscapes linked to the present time with the increasingly common new technologies since all the proposals follow the established process of creative work and technical requirements.

Project Lithica. Laetitia Sauleau-Lara-.Ciutadella de Menorca, 1994—ongoing. It is the project of transformation of the old “marés”quarries, the “pedreres de s'Hostal” (s'Hostal quarries) in Menorca, into an artistic space. The project is based on either the presence or the evocation of the industrial processes that shaped the quarries to create landscapes such as The Mineral Maze by José Bravo which is composed of 3,000 stones of the site (Fig. 9)[8].

10 The Sublime

The sublime. It corresponds to landscapes which are created with extreme technologies that entail a mixture of contemplation of absolute beauty and fascination for the technological challenge that they present. They are close to the sublime in the concept by Edmund Burke inTo Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful(1756). Edmund Burke separates the beauty from the sublime, which affects the consideration of techno landscapes from extreme technologies. He uses Alain Roger's expressions:“in situ” like the Millau Viaduct or“in visu” ( for most of people ) like the Soyuz space station that evokes the sublime. The sublime is “that one that is absolutely big”, according to Kant, and “controlled fear that attracts the soul”or “amazement without danger” for Edmund Burke. This is the intention of the research works on the expression of the intangible that the author develops in the Boboli series (Fig. 10).

This way the current man who, in the fog,goes over the Millau Viaduct, which is at a height of 343 m, experiences the same Romantic feelings as the man on the top of the mountain in the paintingWanderer above the Sea of Fogby Caspar David Friedrich. This way a circle is unexpectedly closed. It is a circle that joins the Romanticism of the 18th century with the extreme technology of the 21st century.

The Millau Viaduct is a project by the architect Norman Foster and the engineer Michel Virlogeux. It is one of the tallest cable-stayed bridges in the world. Due to this and to both its slenderness and design it has become a unique landmark in the landscape of A75 highway[9-10].

11 Permanent Emergency

In the previous approach to landscaping today I intended to explain how, to date, modern landscapes have been formalized from the interpretation of identities that have prevailed over the course of time.

However, we need to take into account the following:the radical changes that have been generated due to the technological (r)evolution at a hectic pace, the new horizons of knowledge,cybernetics, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, etc that have no humanism, and massive consumption of the resources of the planet in which we are immersed. All this generates new unprecedented transformations of the landscapes which are changing continuously. The classical identities are no longer available for them.

This constant transformation together with globalization lead to new emerging identities, called Permanent Emergency generated by hybridisation or permanent mutation whose landscapes are still chaos without being defined.

Hybridisation means the constant interrelation between opposed or different elements of all kinds such as personal, geographical and ethnic with constant and reciprocal mixings. This makes it difficult to recognize stable identities as a starting point of the project and, following Zygmunt Bauman, they could be regarded as liquid identities.

Permanent mutation is expressed with fading,where a new image comes up and it can relate to the previous one or not. Besides it does so when the previous one hasn't vanished completely yet.This happens continuously so that society doesn't really know what they can identify with since an identity, which is stable enough to identify with,doesn't exist. Whereas in the above case instability derived from contact here it is a nearly absolute simultaneity.

One of the reasons of this new conflict is the absence of a humanist conception of the landscape as animist attributes were lost centuries ago. To us an exciting challenge is undoubtedly the construction of a new landscape architecture,which is able to give shapes and create the landscape of these new identities. In my opinion the ecological and environmental connotation is of great importance but reductionist. Although it can establish a trend I don't think it must occupy the centrality of the discipline of landscape architecture or landscaping as the new landscape architecture should form itself as hybrid with all the disciplines that the present contemporaneity offers[11].

Sources of Figures:

Fig. 1© Eugenia Vidal; Fig. 2 © Batlle & Roig; Fig. 3 © Nrao.edu; Fig. 4 © Jean-Pierre Dalbéra; Fig. 5, 6, 10 © Miquel Vidal Pla; Fig. 7 © Beth Gali; Fig. 8 © Australian garden_Taylor_Cully_Lethlean_Cover; Fig. 9 © Jean Pierre Fouquet.

(Editor / LIU Yufei)