The Art of Translation

By Ji Jing

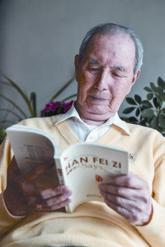

At 91, Lin Wusun is a staunch advocate of somersaults, that is, mental somersaults, his name for the act of translating.

An eminent communicator who spent his career explaining Chinese culture to foreigners and the Western way of thinking to Chinese, Lin donned a translators mantle after retirement, became a foremost Chinese translator, and still keeps his hand in.

Currently, he is translating the works of ancient Taoist philosophers. The work is not as ancient as it sounds for the philosophers used a good deal of fables to drive their lessons home and some of them, like the story of the old man who decided to move a mountain that was in his way, is used by Chinese even today, much like Aesops fables.

“But not all of the fables are well-known,” he said. “While some of these fables and proverbs are easy to translate, like ‘a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, [attributed to Lao Zi], some are not so easy and require clarifi cation.”

It makes sense that Lin is translating philosophers; he likes challenges. They have been part of his life.

Taught by war

When Lin grew up in Tianjin, a port city in north China, he witnessed the Japanese aggression and peoples suffering. He recalled seeing corpses fl oating in the Haihe River. They were the bodies of Chinese laborers forced to build military infrastructure for the Japanese and killed after the work was done.

In 1939, Lin moved with his father, who was a banker, to Shanghai. Later, the family moved to India and from there he went to the U.S. by ship to study philosophy at Dartmouth College. The ship passed through Shanghai where, to his joy, he saw many Chinese students coming aboard, also headed for the U.S. That was in 1946 and three years later, the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) was born.

That marked a change in the exodus. Chinese scientists and other professionals who had studied overseas began returning to contribute to the building of the nation and Lin was among them. His work was to introduce China to the outside world as an interpreter, journalist and translator.

“I experienced the war and witnessed how China was invaded and bullied. So when the PRC was founded, I thought I should play a role in the development of the nation,” he said. As a philosophy major, he thought he could explain the Western way of thinking and explain China to the West.

In 1952, when the PRC hosted its fi rst international conference, the Asia and Pacific Rim Peace Conference, he provided simultaneous interpretation.

After Beijing Review, Chinas first Englishlanguage newsweekly, was launched in 1958, he worked as a journalist and eventually became president of the organization running the magazine. He was president of China International Publishing Group, a media conglomerate established to communicate with international audiences, from 1988-93, taking up translating ancient Chinese classics and contemporary works after retirement. He was also executive vice president of the Translators Association of China (TAC) from 1992 to 2004. In 2011, the TAC presented him the Lifetime Achievement Award in Translation, the top honor conferred by the association.

Explaining ancient wisdom

Among his best known works is his English translation of The Art of War. Described as Asias most famous ancient military treatise, it was written by Chinese general Sun Zi during the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 B.C.) and remains relevant even today, included in military and business courses in different parts of the world and studied by athletes and CEOs.

When Lin began the translation, there were things he couldnt understand. So he sought out a military expert at a research institute to explain them. This would become characteristic of his work.

In 1972, wooden slips of another military treatise, also called The Art of War, were unearthed in Shandong Province in east China. It was written by Sun Bin, said to be a descendant of the first writer, in the Warring States Period(475-221 B.C.). Lin translated the newly discovered text as well, producing the first English translation of this classic.

Translation, he said, means incessantly searching for the best rendition and the most apt word. In addition to being loyal to the original text, a translator needs to use the language that is in use. Lins translations often feature his own interpretation, with the aim of sharing with readers what he has learned as he studied the original text.

The Analects of Confucius, selected sayings of the Chinese philosopher thought to have been compiled by his followers, has been translated by many. But Lins version still stands out. Confucius Says: The Analects, published by the Foreign Languages Press, has the contents rearranged according to the subject matter and also includes the story of the philosophers life and influence on the Chinese psyche. Then, in keeping with the modern tone of the title, it offers a comparison between Confucius, Jesus and Socrates.

This was a long project. To understand the book, he said he needed to read other books. Then dissatisfied with his earlier drafts, he revised it fi ve times, the entire work taking him 10 years before it fi nally went to press.

Academics have praised Lins distinctive style. In a paper on the translation of The Analects, published in Journal of Xiangtan University in 2014, researchers Xu Lei and Tu Guoyuan noted that Lins version highlights his own cultural identity. He tried to not only make the Confucian text more readable and accessible, but also interpret Chinese wisdom in a more authentic way by avoiding excessively borrowing Western philosophical terms.

A realistic approach

In 2005, Luis Palau, a U.S. Christian evangelist, and Zhao Qizheng, then Minister of the State Council Information Offi ce, held a dialogue on philosophy, history and religion. The outcome was a book titled Riverside Talks.

Lin was invited to translate the book. However, he faced a problem. Palaus original conversation was not available. It had been translated from English into Chinese and Lin was forced to translate the Chinese version back into English, trying to make it as close to the original as possible.

He tried to imagine what Palau had said and make the translation colloquial and lucid. In this, he was helped by his wife Zhang Qingnian, who had also studied in the U.S. and after returning to China worked as an English-language broadcaster.

After the translation was completed, it was shown to Palau. According to Huang Youyi, Vice President of the China Academy of Translation, who coordinated the project, the evangelist said he was surprised to fi nd the translated version was exactly what he had said, even better.

“I recommended Lin for translating the book because he studied philosophy in the U.S. in the 1940s. He fi nished the task, which would have been almost mission impossible for others, with ease and even corrected the mistakes in the Chinese translation [of Palaus conversation],” Huang said.

When he translated a book on Pudong, Shanghai, Lin adopted his signature approach.

The book chronicles the development and opening up of Pudong New Area, an emerging economic hub with some of the tallest skyscrapers in the world. So Lin went to Pudong to see developments on the ground for himself.

“In this way I could understand the examples given in the book much better. Had I only read the book without going to the place, it would have felt as if there was a layer separating me from reality,” he said.

Besides Chinese and English, Lin learned French as an optional course at university. Every day, along with his translation and other work, his routine includes reading the news in English and French.