Complementary and alternative medicine applications in cancer medicine

Milena Jurisevic, Sergey Bolevich

Complementary and alternative medicine applications in cancer medicine

Milena Jurisevic1*, Sergey Bolevich2

1Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac 34000, Serbia.2Department of Human Pathology, the Federal State Autonomous Education Institution of Higher Training, the First Sechenov Moscow State Medical University at the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University), Moscow 119991, Russia.

Besides conventional medicine, many patients with cancer seek complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as an additional treatment option. Since the early 1970s, the use of CAM in cancer treatment has expanded worldwide. CAM, as a tempting option, was used by patients with cancer mainly due to easy accessibility. Patients with cancer used CAM to achieve better quality of life or to find a cure. As physicians are mainly unaware of CAM use by patients, doctor-patient communication about CAM use should be brought to a higher level. To identify circumstances in which CAM are preferred, further investigations are needed especially in biologically based therapies. Clinical-based evidence for mind-body therapies have been established, so this type of CAM can be recommended for patients with cancer during chemotherapy. Future studies are necessary to fill the gaps so that CAM users, as well as medical experts, are in position to clearly determine all the benefits and disadvantages of the mentioned therapy.

Complementary and alternative medicine, Cancer, Breast cancer, Safety

(1) The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is growing rapidly especially among younger female patients with cancer with higher education.

(2) Most patients with cancer consider CAM as a harmless option in their healing process, which is not always the case.

(3) Clinical-based evidence for mind-body therapies has been established, and this type of CAM can be 、recommended for patients with cancer during chemotherapy.

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) plays an important role in the prevention and treatment of diseases since the ancient times. In the 16th-11th century B.C.E., there were earliest notes of tumors and their treatment methods were described by traditional Chinese practitioners. It has been known that herbal medicine are used in Egypt and in traditional Chinese medicine since 4500 B.C.E. Since the early 1970s, the use of CAM in cancer treatment has expanded worldwide. Numerous studies point to the benefits of Ayurveda yoga in patients with cancer, improving quality of life. China acupuncture has been shown beneficial in controlling vomiting and pain in patients with cancer. Reflexology, which was practiced for years by followers of Chinese, Egyptian, and Indian medicine, has been successfully used to relieve pain in patients with cancer. Mushroom Agaricus blazei has been mostly used in Japan but is currently in the first phase of the clinical trial in patients with cancer.

Background

Cancer is presently one of the most widespread and feared diseases. For years, it is the leading cause of mortality worldwide. According to the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Statistics Center in USA, there will be 4,380 new cases of cancer and 1,660 cancer deaths daily in 2019 [1]. The second leading cause of cancer death in women is breast cancer [2]. Although presently many cancers are successfully treated, some patients are limited to palliative therapy. The fact that, currently, in the USA, there are more than 3.1 million breast cancer survivors and that new therapeutic and diagnostic approaches give hope that this number will continuously increase over time [2]. It is known that the diagnosis of cancer and the whole pathway affects the psychological, physical, and emotional state of the patient and therefore the quality of life. Besides conventional effects, cancer therapy leads to a number of serious adverse events, and therefore, patients with cancer may turn to nonconventional therapies. This review summarized the reasons for the use of CAM and its potential adverse effects based on papers published in the last 18 years.

The definition of CAM

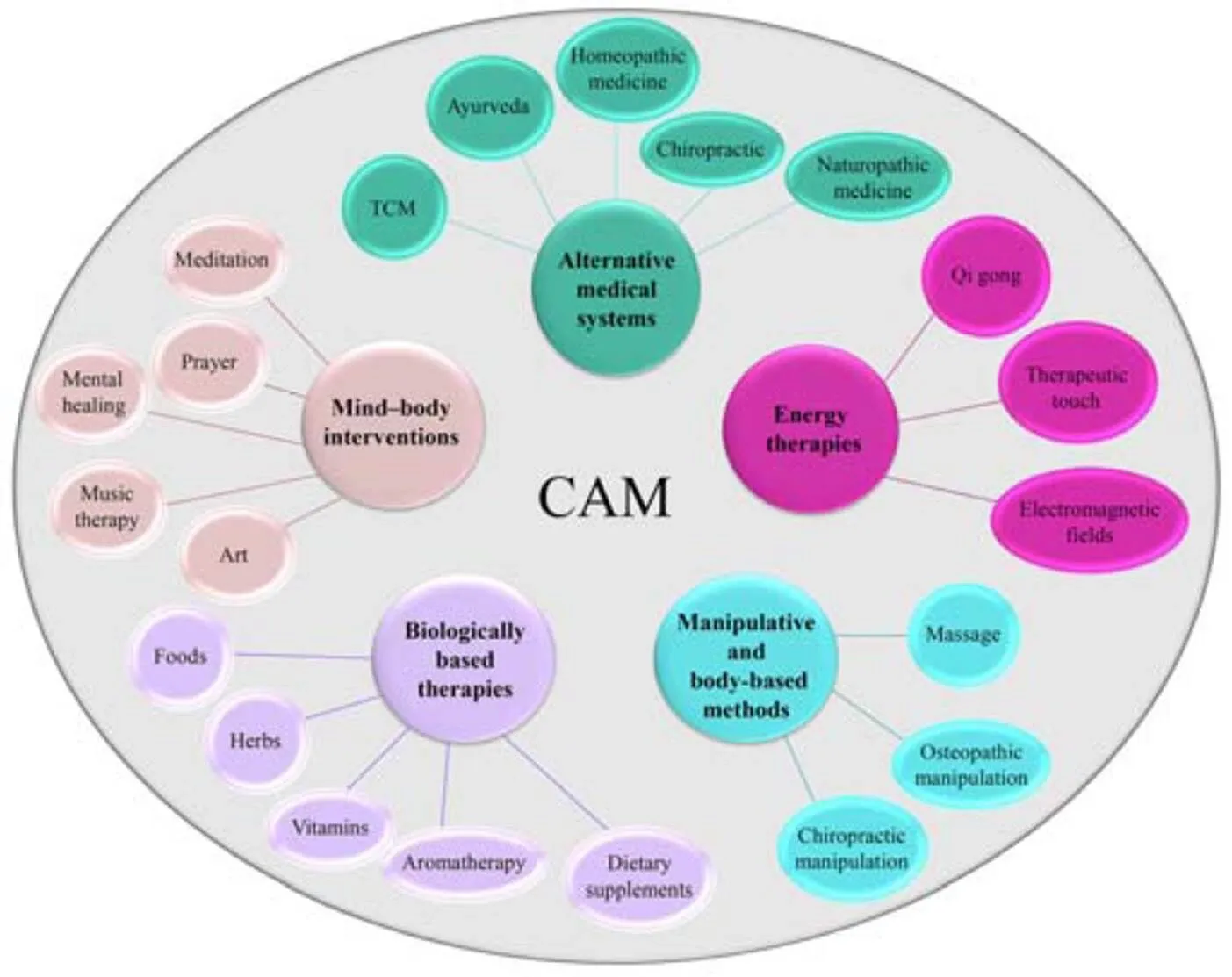

Although it is considered that complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use is beyond the scope of traditional medicine, researchers are mainly referring to the CAM definition provided by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), USA. According to the NCCIH, CAM must be seen as“health care approaches that are not typically part of conventional medical care or that may have origins outside of usual Western practice”[3]. Another more complex definition is derived from Ernst. who see CAM as a“group of diverse medical and health care approaches and products that are not typically part of conventional medical care”[4]. “Complementary” therapy is usually considered as an adjunct to conventional treatment or supplemental therapy that can reduce some of the difficulties that the patient has. In contrast, “alternative” therapy is considered as an approach that will replace conventional therapy [3]. Moreover, the present term “integrative medicine” that involves the use of evidence-based CAM in combination with conventional medicine is becoming more widespread. According to the NCCIH, CAM therapies are classified into five domains (Figure 1).

The time of decision making of CAM use by patients with cancer has not yet been accurately determined. Patients with cancer use CAM regardless of the stage of the disease [5]. Usually, some patients with cancer start with CAM therapy 4-6 months after initiating conventional treatment or after disease progression [5]. The most incautious reasons for resorting to CAM therapy are better quality of life, remediation of side effects, control of cancer symptoms, and end-of-life care [5]. It is interesting that among BRCA (breast cancer type 2 susceptibility protein) mutation healthy women, the frequency of using CAM is comparable to that of patients and survivors with breast cancer [6].

Figure 1 Classification of CAM

CAM, Complementary and alternative medicine.

Historical background of CAM

The use of CAM plays an important role in the prevention and treatment of diseases since the ancient times. In the 16th-11th century B.C.E., there were earliest notes of tumors and their treatment methods were described by traditional Chinese practitioners [7].

It is believed that aromatherapy establishments were established in Egypt around 1600 B.C.E. [8]. Aromatherapy was also used in Chinese and Greek medicine. Aromatherapy is based on the use of oils obtained from various plants with the enhancement of the physical and emotional state of the user [3, 9]. Aromatics massage is also one of the fundamental aspects of traditional Indian medicine known as “Ayurveda” or “medicine of the Gods.” The roots of Ayurveda as a special Hindu medical system date back to the 6th century, and presently, it is used globally. Ayurvedic medicine can include various therapeutic approaches such as use of special diets, specific Ayurvedic medications that may contain some heavy metals such as mercury or arsenic, various herbal therapies, meditation, yoga, or urine therapy [8]. As an integral part of Ayurveda yoga has been practiced for years to promote psycho-physical health, but it cannot be disputed that recently it has become more popular. Numerous studies point to the benefits of yoga in patients with cancer, stressing that this type of CAM drastically improve quality of life [9]. When it comes to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which is practiced by millions of people, acupuncture takes a significant place. Acupuncture is actively used for more than 4700 years, but in 1971, there was a boom worldwide. According to the Chinese tradition, it is believed that the benefits of acupuncture are due to a constant energy flow. Numerous studies and clinical trials suggested that acupuncture has been beneficial in controlling vomiting and pain in patients with cancer [10]. Moxibustion and acupressure that are based on the principles of acupuncture also have a foothold in TCM [8]. It has also been shown that reflexology, which was practiced for years by followers of Chinese, Egyptian, and Indian medicine, has been successfully used to relieve pain in patients with cancer [11]. Judging by the results of the recently published study, after diagnosis, patients with cancer usually prefer herbal-based CAM type [12]. The herbal medicine used today is based on “traditional Chinese herbalism, Ayurvedic herbalism, Western herbalism (came from Greece and Rome) and Arab traditional medicine” [13]. An ancient book of medicine, which laid the foundations of herbal medicine in China in 2700 B.C.E., describes the therapeutic effects of more than 300 plants [8]. Dioscorides, a Greek physician, wrote De Materia Medica. This pharmacopoeia was widely read for 1500 years and is considered as standard reference of herbal medicine [8]. Greek medicine used diluted opium as anesthetic/pain killer, while Indian medicine considered belladonna a medication of choice for the relief of pain. Among patients with cancer, especially women with breast cancer, most used herbal medicines are Echinacea, garlic, Jianghuang (, green tea,Renshen ()flax seed or oils, ginger, and others [12,14].

Patterns of CAM use

Since the early 1970s, the use of CAM in cancer treatment has expanded worldwide [15]. Of patients with cancer, 30% to even 80% use some form of CAM in order to relieve treatment-related symptoms [16–22]. The enormous variability in the prevalence of CAM use is a consequence at least partly due to the methodological variability of published studies and inconsistent definition of CAM. Some authors questioned only the use of herbal preparations, while others included it in their body-based practices. Even today, CAM use is rapidly expanding. Various systematic reviews concluded that the use of CAM has been increasing from 25% of patients with cancer in 1990 to 49% in 2000-2009 [23] and 51% in 2009-2018 [24]. Additionally, CAM use is determined by geography [23]. It has been hypothesized that geography-related CAM use may be a result of different cultural viewpoints toward health and most of all accessibility of conventional and CAM therapies [17, 25–30]. For example, it is well known that Kampo medicine and acupuncture are covered by public health insurance in Japan unlike in Western countries. In contrast, chiropractic and osteopathy, which are known to be widespread in the USA, are not recognized in Japan [31]. Moreover, in Taiwan, TCM is highly adopted and available mainly because it is covered by the insurance program [32]. In some countries, such as Nigeria, CAM is used as primary healthcare [33]. Furthermore, several studies indicate that German-speaking countries have a high prevalence of CAM use compared to other European countries. The main stronghold of this hypothesis lies in the fact that homeopathy, anthroposophic medicine, and naturopathy have their bassinet in these countries [34]. Moreover, different cultural viewpoints indicate that various patients have a different idea of what CAM may be. For example, Turkish patients with cancer did not regard indigenous herbal remedies as CAM unlike Indo-Asian patients with cancer [35, 36]. When it comes to dietary supplements, it is well known that, in USA, using Yinxing (), echinacea, garlic, Renshen (), soybean, St John’s wort, valerian, green tea, and ginger is extremely popular [37], while, in Japan, Agaricus blazei, beer yeast, propolis, Japanese plum, and chlorella are highly used [38]. Since 1991, mushroom Agaricus blazei has been mostly used in Japan but is currently in the first phase of the clinical trial in patients with cancer [39]. Interestingly, Danggui (), with its immunomodulatory effects, is still a dietary supplement in USA, while it is considered as a medicine in Japan [31].

Reasons for CAM use

It is also clear that patient’s conception of CAM therapies may be different from those of health care professionals. CAM treatments are poorly used by conventional healthcare experts [40]. Literature suggests on the fact that physicians discuss CAM use to patients with cancer [41–43]. This is probably the consequence of several associated barriers: the use of CAM is not their field of interest [44, 45]; they believe that the CAM use does not have support in evidence-based medicine [46], or time is inadequate for CAM use during patients’ checkups [47]. However, the crucial moment in decision making regarding the use of CAM in patients with cancer is the time of cancer diagnosis [48]. For patients with cancer, increased psychosocial stress and less hopeful prognosis remain the main reasons for using this kind of therapy. Most users believe that CAM use can provide hope and psycho-spiritual well-being and improve the quality of life [49]. Mainly, patients with cancer want to achieve faster recovery, strengthen the immune system, reduce the side effects of conventional therapies, and silence the fear that the disease will not be under control [48, 50]. Anxiety disorders, chronic pain, and metastatic form of disease are also associated with CAM use. According to literature, female sex, younger age, and high education level are strongly associated with CAM use [51–55]. Study results indicate that women use CAM more frequently than men [56]. High education level and younger age are often associated with easier use of social platforms, media, internet, and medical information. Another theory is based on the economic side of CAM use. It is known that, in most countries or cultures, patients purchase CAM by themselves. This information suggests that patients with higher education level are also patients with higher incomes, which can afford continuous CAM cost.

Economic insight of CAM use

The most commonly used types of CAM are dietary supplements and mind-body practices. Dietary supplements include use of vitamins, minerals, herbal and/or botanical supplements/medicines, and other over-the-counter natural products, while other groups mainly include yoga, meditation/spiritual healing, acupuncture, massage, and reiki [3, 57]. Dietary supplements are often registered as over-the-counter products indicating that economical cost of this type of CAM goes to the user’s expense [58]. In Thailand, patients with cancer need to spend about 200 USD/month for CAM use [59], between 100 to 300 Euros/month in Italy [43], and 50 to 150USD/month in rural Australia [60]. The allocation for this type of therapy is different and reported primarily from the health system. In 1997, in the USA, the total cost of CAM for patients was 27 billion USD [61], and they are followed by the costs in Europe as the second largest market in 2001 [62]. Besides that, the total budget of the NCCIH increased from 50 million USD in 1999 to 120 million USD in 2006 to 146.5 million USD in 2019, reflecting the interest in CAM use at all levels of the beneficial chain [3]. It is very clear that economic impact of CAM use is huge. If we exclude phytomedicine, which has been shown to be pharmacoeconomically justified [63], in 2017, Huebner. concluded that they “did not find any arguments in the literature that were directed at the economic analysis of CAM in oncology” [64].

Safety of CAM use

An interesting fact is that about 65% of users in Ireland had a “might help, can not hurt” attitude toward CAM [65]. It is clear that CAM use can help patients with cancer in different ways but can also carry certain risks especially when it comes to dietary supplements and herbal remedies. Dietary supplements and herbal remedies are ingested substances that increase the risk of certain adverse effects and interactions with conventional chemotherapy. Berretta. reported that, in Italy, 86% of CAM users were unaware of the possible side effects of CAM use [43]. If we add to this the fact that most patients (43% in Berretta’s study [43] or 50% in Davis’ [66] do not tell their physician about the use of CAM, it is quite certain that they are at higher risk of developing adverse events [43]. Sometimes, the side effects of CAM use, such as vomiting, nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, may be perceived as adverse effects of conventional therapy. The scenario that follows is that a physician discontinues using conventional therapy because of the side effects. According to the American Cancer Society in 2012, more than 2800 adverse events of dietary supplements were reported [67]. For example, it has been reported that echinacea, soybean, or St. John’s wort caused anaphylaxis [68]. Garlic, Renshen (), ginger, and kava kava ()caused gastrointestinal side effects. Valerian caused hepatotoxicity. Obstruction of the sigmoid colon has been reported after treatment with grape seed [68]. Moreover, probiotic sepsis has been observed in immunocompromised patients soon after probiotics have been used by patients with cancer to relieve chemotherapy-induced diarrhea [69, 70]. Furthermore, it has been observed that garlic, aloe vera, aromatherapy, Yuejiancao (), and cod liver oil caused vomiting in patients with cancer [43, 71]. Flu-like syndrome has also been noted in patients with cancer after using St. John’s wort or cod liver oil [71]. Pain and inflammation were reported by these patients after massage, chiropractic, or use of valerian products [71].

Moreover, due to possible interactions, some CAM may potentially affect the metabolism of chemotherapy agents, causing more toxic or either subtherapeutic effects of conventional drugs [72, 73]. There are two most common mechanisms of interaction formation at the pharmacokinectic level: P-glycoprotein and cytochrome P450 CYP enzyme interactions [74–83]. It is well known that green tea, Yinxing (), reishi mushroom, and grape seed are CYP3A4 inhibitors, so they can easily increase the risk of toxicity of dasatinib, imatinib, docetaxel, or vinca alkaloids. In contrast, CYP3A4 inducers include echinacea and St John’s wort so they can interact with cyclophosphamide and other previously mentioned chemotherapeutic agents. Cannabinoids seem to be a CYP2C9 inducer, so they can easily increase the risk of overdose of prodrugs cyclophosphamide and tamoxifen [74–83]. Curcumin and milk thistle are CYP2C9 inhibitors. Ginger can also increase bleeding risk during warfarin therapy. Another problem in herbal medicine is the belief that it is better to use original plant tissues instead of isolated individual active ones [84]. In most cases, it is not possible to isolate all active ingredients from different plants and monitor their metabolism, so a problematic interaction may occur between unknown secondary constituents of herbal medicines and standard cancer treatment [85, 86].

CAM use in patients with breast cancer

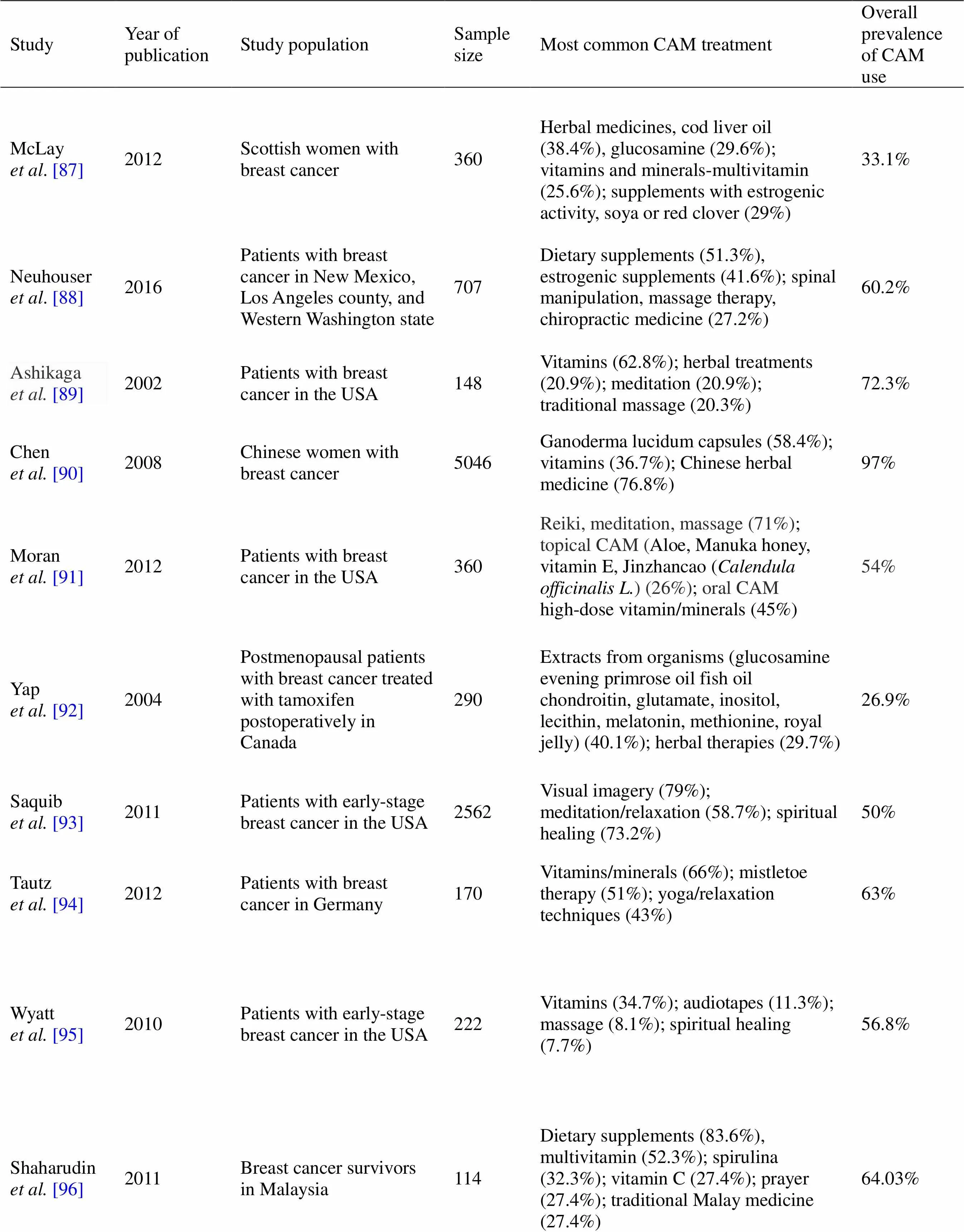

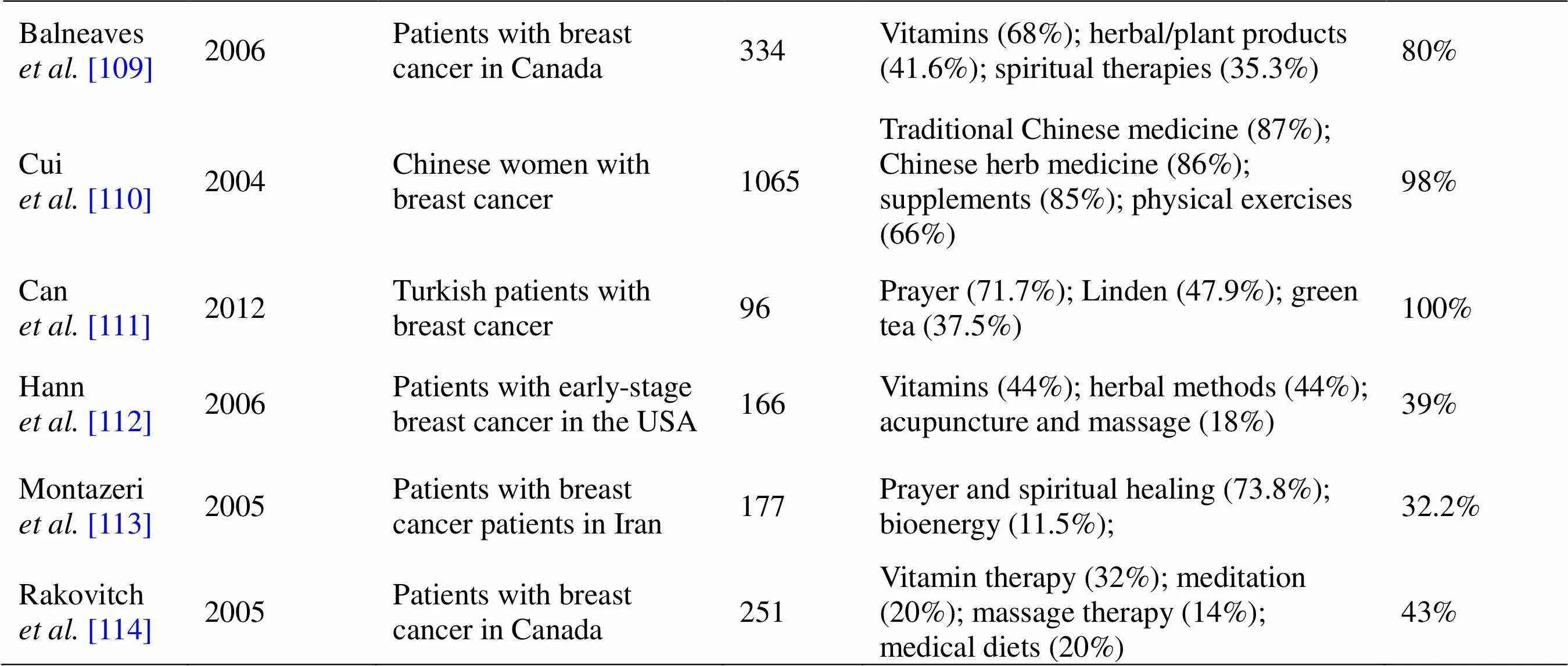

The use of CAM was highest in patients with breast cancer. The prevalence of CAM use in patients with breast cancer varies from 30% to > 90%. It is known that women are the most frequent users of CAM, including biologically based CAM (vitamins, minerals, herbal medicine), followed by some types of mind-body medicine-prayer, meditation, and spiritual healing (Table 1). Women with breast cancer are less likely to be defined in energy medicine. In addition to the fact that many researchers use different classifications of CAM in their studies, they are usually omitted from changes in diet of patients. As information sources, patients with breast cancer seek guidance from family and friends, self-help groups, health professionals, and CAM providers [87–114]. Interestingly, it has been shown that patients consult their preferred physician if they desire to use herbal medicine. On the contrary, they did not report use of body-based practices, massage spiritual healing, hypnosis, or acupuncture to a physician [115]. This may increase the awareness of women about potential adverse reactions of CAM. According to previous insights, younger women with higher education level seemed to be more attracted to CAM use. Younger women with breast cancer also were more easily accommodated in spiritual techniques. There are indications that income stage, marital status, and private health insurance are predictors of CAM use among these patients. The main reasons for CAM use among patients with breast cancer were promotion of emotional health, reduction of conventional medicine side effects, and healing. Contrasting opinions were available on correlations between the use of CAM and poorer emotional functioning [113, 114]. It has been reported that patients with breast cancer were more likely to use CAM if they were depressed [113]. On the contrary, anxiety and depression were not related to CAM use in patients with breast cancer [114]. Different contradictions and lack of awareness suggest the need to appropriately increase evidence-based medicine information on CAM.

CAM use with evidence

The autonomic use of CAM did not bring much benefit to the patient with cancer [116]. Meanwhile, it is possible to find some encouraging evidence that some CAM may be beneficial if they were used as additional therapy to standard cancer therapy to relieve cancer-related symptoms and side effects of conventional cancer therapy [117–119].

Recently, scientists have been attempting to obtain as much information as possible on the pharmacological mechanism and medical-based evidence on the efficacy of herbal remedies. To date, it is known that dry extract of guarana may be used to resolve chemotherapy-related fatigue [120]. Patients with radiation-induced mucositis treated with aloe vera mouthwash showed similar recovery rates as patients who used benzydamine as a gold standard [121]. Compared to placebo, ginger reduced nausea during chemotherapy [122]. High doses of curcumin and quercetin in patients with adenomatous polyposis reduced the number and size of polyps [123]. Renshen () may improve cancer-related fatigue [124]. Fish oil supplement can be used to treat chemotherapy-induced cachexia [125]. Lavandula officinalis oil can be used as an alternative to relieve anxiety [126]. Furthermore, there is some evidence suggesting that Honghua () may be useful in depression remediation [127]. Ruxiang (also can reduce fibroadenoma size [128].species also increased cytotoxicity of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in vitro [129]. Homeopathic medicine may be useful in patients with breast cancer, particularly in relieving menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and headaches [130] although literature shows contrasting opinions [131].

In breast cancer treatment, dietary supplements did not show great clinical benefit, but psychological and emotional conditions improved and quality of life was obtained after mind-body practices. Music therapy, meditation, and yoga can reduce anxiety in patients with cancer [132–134]. Yoga also has beneficial effects when it comes to mood, sleep disturbance, and quality of life, as well as fatigue [135]. Acupuncture may be considered to reduce hot flashes, pain, nausea and vomiting, and fatigue [136–138]. Quality of life in patients with cancer can be improved by meditation [139]. Massage reduced nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy [140].

Table 1 Prevalence of CAM use by patients with breast cancer

Table 1 Prevalence of CAM use by patients with breast cancer (continued)

NA, not available.

Clinical trials that would properly test the efficacy of CAM are challenging mainly because it requires time, care, and money [141–143]. Some modalities of CAM, especially herbal medicines, are classified as over-the-counter products so manufacturers are allowed to obtain health claims without evidence. Patients often consider CAM therapy as absolutely safe and highly effective. The attribute of this attitude is contributed by the so-called placebo effect, that is, the psychological flaw that they have performed something to their own health and that it greatly helps them. The placebo effect allows the patient to feel better at least a couple of hours and can often be the main trigger for using CAM although it is recognized that such treatment does not help the underlying disease. Due to the placebo effect, it can often affect the results of clinical trials if they are not well placed methodologically. Finally, the patient’s awareness of clinical studies of different CAM modalities seems to be low [144]. Considering the rapid development of CAM and oncology treatment, in the future, adequate and methodologically precise clinical studies seem to be indispensable.

Conclusion

The use of CAM is growing rapidly especially among younger female patients with cancer with higher education level. Most patients with cancer consider CAM as a harmless option in their healing process. They may never share information about using CAM with the physician, unless they are explicitly asked. This information may be troubling because some CAMs can interact with conventional cancer therapy. Since physicians are mainly unaware of CAM use by patients, physician-patient communication about CAM use should be brought to a higher level. In order to identify circumstances in which CAM are being preferred, further investigations are needed especially in biologically based therapies. Clinical-based evidence for mind-body therapies have been established so this type of CAM can be recommended in patients with cancer during chemotherapy.

1. American Cancer Society [internet]. Cancer Facts & Figures ACS American Cancer Society [cited 2019 June 2]. Available from: https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/#!/

2. American Cancer Society [internet]. About Breast Cancer American Cancer Society [cited 2019 June 2]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/CRC/PDF/Public/8577.00.pdf

3. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health [internet]. Definition of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) [cited 2019 June 2]. Available from: https:// nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health

4. Ernst E, Pittler MH, Wider B,. The desktop guide to complementary and alternative medicine, 2nd edition. Edinburgh: Elsevier Mosby, 2006.

5. Richardson MA, Straus SE. Complementary and alternative medicine: opportunities and challenges for cancer management and research. Semin Oncol 2002, 29: 531–545.

6. Mueller CM, Mai PL, Bucher J,. Complementary and alternative medicine use among women at increased genetic risk of breast and ovarian cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med 2008, 8:17.

7. Li P. Management of cancer with Chinese medicine. United Kingdom: Donica Publishing, 2003.

8. Oumeish OY. The philosophical, cultural, and historical aspects of complementary, alternative, unconventional, and integrative medicine in the Old World. Arch Dermatol 1998, 134: 1373–1386.

9. Agarwal RP, Maroko-Afek A. Yoga into Cancer Care: A Review of the Evidence-based Research. Int J Yoga 2018, 11: 3–29.

10. Tas D, Uncu D, Sendur MA,. Acupuncture as a complementary treatment for cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014, 15: 3139–3144.

11. Bao Y, Kong X, Yang L,. Complementary and alternative medicine for cancer pain: an overview of systematic reviews. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014, 2014: 170396.

12. Buckner CA, Lafrenie RM, Dénommée JA,. Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients before and after a cancer diagnosis. Curr Oncol 2018, 25: e275–e281.

13. Saad B, Azaizeh H, Said O. Tradition and perspectives of arab herbal medicine: a review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2005, 2: 475–479.

14. Shareef M, Ashraf MA, Sarfraz M. Natural cures for breast cancer treatment. Saudi Pharm J 2016, 24: 233–240.

15. Sparber, A, Wootton JC. Surveys of complementary and alternative medicine: Part II. Use of alternative and complementary cancer therapies. J Altern Complement Med 2001, 7: 281–287.

16. Maggiore RJ, Gross CP, Togawa K,. Use of complementary medications among older adults with cancer. Cancer 2012, 118: 4815–4823.

17. Can G, Erol O, Aydiner A,. Quality of life and complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer patients in Turkey. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2009, 13: 287–294.

18. Sokol KC, Knudsen JF, Li MM. Polypharmacy in older oncology patients and the need for an interdisciplinary approach toside-effect management. J Clin Pharm Ther 2007, 32: 169–175.

19. Wyatt GK, Friedman LL, Given CW,. Complementary therapy use among older cancer patients. Cancer Pract 1999, 7: 136–144.

20. Posadzki P, Watson LK, Alotaibi A,. Prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by patients/consumers in the UK: systematic review of surveys. Clin Med (Lond) 2013, 13: 126–131.

21. Bonacchi A, Toccafondi A, Mambrini A,. Complementary needs behind complementary therapies in cancer patients. Psychooncology 2015, 24: 1124–1130.

22. Pan SY, Gao SH, Zhou SF,. New perspectives on complementary and alternative medicine: an overview and alternative therapy. Altern Ther Health Med 2012, 18: 20–36.

23. Horneber M, Bueschel G, Dennert G,. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Integr Cancer Ther 2012, 11: 187–203.

24. Keene MR, Heslop IM, Sabesan SS,. Complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer: A systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2019, 35: 33–47.

25. Stein KD, Kaw C, Crammer C,. The role of psychological functioning in the use of complementary and alternative methods among disease-free colorectal cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society's studies of cancer survivors. Cancer 2009, 115: 4397–408.

26. Liao YH, Lin CC, Li TC,. Utilization pattern of traditional Chinese medicine for liver cancer patients in Taiwan. BMC Complement Altern Med 2012, 12: 146.

27. Lafferty WE, Bellas A, Baden AC,. The use of complementary and alternative medical providers by insured cancer patients in Washington State. Cancer 2004, 100: 1522–1530.

28. Lafferty WE, Tyree PT, Devlin SM,. Complementary and alternative medicine provider use and expenditures by cancer treatment phase. Am J Manag Care 2008, 14: 326–334.

29. Kav S, Pinar G, Gullu F,. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with gynecologic cancer: is this usage more prevalent? J Altern Complement Med 2008, 14: 347–349.

30. Tarhan O, Alacacioglu A, Somali I,. Complementaryalternative medicine among cancer patients in the western region of Turkey. J Buon 2009, 14: 265–269.

31. Suzuki N. Complementary and alternative medicine: a Japanese perspective. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2004, 1: 113–118.

32. Liao YH, Li CI, Lin CC,. Traditional Chinese medicine as adjunctive therapy improves the long-term survival of lung cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2017, 143: 2425–2435.

33. Aliyu UM, Awosan KJ, Oche MO,. Prevalence and correlates of complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer patients in usmanu danfodiyo university teaching hospital, Sokoto, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2017, 20: 1576–1583.

34. Yarney J, Donkor A, Opoku SY,. Characteristics of users and implications for the use of complementary and alternative medicine in Ghanaian cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy and chemotherapy: a cross- sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013, 13:16.

35. Samur M, Bozcuk HS, Kara A,. Factors associated with utilization of nonproven cancer Therapies in Turkey. Support Care Cancer 2001, 9: 452–458.

36. Warrick PD, Irish JC, Morningstar M,. Use of alternative medicine among patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999, 125: 573–579.

37. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Du M,. Trends in dietary supplement use among US adults from 1999–2012. JAMA 2016, 316: 1464–1474

38. Hyodo I, Amano N, Eguchi K,. Nationwide survey on complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients in Japan. J Clin Oncol 2005, 23: 2645–2654.

39. Ohno S, Sumiyoshi Y, Hashine K,. Phase I Clinical Study of the Dietary Supplement, Agaricus blazei Murill, in Cancer Patients in Remission. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011, 2011: 192381.

40. Zollman C, Vickers A. ABC of complementary medicine. Complementary medicine and the patient. BMJ 1999, 319: 1486–1489.

41. Schultz JD, Stegmuller M, Faber A,. Complementary and alternative medications consumed by patients with head and neck carcinoma: a pilot study in Germany. Nutr Cancer 2012, 64: 377e.

42. Hann D, Baker F, Denniston M. Oncology professionals’ communication with cancer patients about complementary therapy: a survey. Complement Ther Med 2003, 11: 184–190.

43. Berretta M, Della Pepa C, Tralongo P,. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in cancer patients: An Italian multicenter survey. Oncotarget 2017, 8: 24401.

44. Molassiotis A, Ozden G, Platin N,. Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients with head and neck cancers in Europe. Eur J Cancer Care 2006, 15: 19e24.

45. Shakeel M, Newton JR, Bruce J,. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients attending a head and neck oncology clinic. J Laryngol Otol 2008, 122: 1360e4.

46. Gaboury I, April KT, Verhoef M. A qualitative study on the term CAM: is there a need to reinvent the wheel? BMC Complement Altern Med 2012, 12: 131.

47. Farooqui M, Hassali MA, Abdul Shatar AK,. Complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) disclosure to the health care providers: a qualitative insight from Malaysian cancer patients. Complement Therap Clin Pract 2012, 18: 252e6.

48. Smith PJ, Clavarino A, Long J,. Why do some cancer patients receiving chemotherapy choose to take complementary and alternative medicines and what are the risks? Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2014, 10: 1–10.

49. Arikan F, Uçar MA, Kondak Y,. Reasons for complementary therapy use by cancer patients, information sources and communication with health professionals. Complement Ther Med 2019, 44: 157–161.

50. Firkins R, Eisfeld H, Keinki C,. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients in routine care and the risk of interactions. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2018, 144: 551–557.

51. Ben-Arye E, Polliack A, Schiff E,. Advising patients on the use of non-herbal nutritional supplements during cancer therapy: A need for doctor-patient communication. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013, 46: 887–896.

52. O'Callaghan V. Patients' perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine. Cancer Forum 2011, 35: 44–47.

53. Poonthananiwatkul B, Howard RL, Williamson EM,. Cancer patients taking herbal medicines: A review of clinical purposes, associated factors, and perceptions of benefit or harm. J Ethnopharmacol 2015, 175: 58–66.

54. Verhoef MJ, Balneaves LG, Boon HS,. Reasons for and characteristics associated with complementary and alternative medicine use among adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Integr Cancer Ther 2005, 4: 274–286.

55. Bishop FL, Rea A, Lewith H,. Complementary medicine use by men with prostate cancer: A systematic review of prevalence studies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2011, 14: 1–13.

56. Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Hedderson MM,Types of alternative medicine used by patients with breast, colon, or prostate cancer: predictors, motives, and costs. J Altern Complement Med 2002, 8: 477–485.

57. Molassiotis A, Fernadez-Ortega P, Pud D,. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol 2005, 16: 655–663.

58. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Association between use of unconventional therapies and conventional medical services. JAMA 1999, 282: 651–656.

59. Puataweepong P, Sutheechet N, Ratanamongkol P. A survey of complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer patients treated with radiotherapy in Thailand. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012, 2012: 670408.

60. Sullivan A, Gilbar P, Curtain C. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in Cancer Patients in Rural Australia. Integr Cancer Ther 2015, 14: 350–358.

61. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL,. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA 1998, 280: 1569–1575.

62. Reilly D. Comments on complementary and alternative medicine in Europe. J Altern Complement Med 2001, 7: S23–S31.

63. Chaudhary T, Chahar A, Sharma JK,. Phytomedicine in the Treatment of Cancer: A Health Technology Assessment. J Clin Diagn Res 2015, 9: XC04–XC09.

64. Huebner J, Prott FJ, Muecke R,. Economic Evaluation of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Oncology: Is There a Difference Compared to Conventional Medicine? Med Princ Pract 2017, 26: 41–49.

65. Amin M, Glynn F, Rowley S,. Complementary medicine use in patients with head and neck cancer in Ireland. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2010, 267: 1291–1297.

66. Davis EL, Oh B, Butow PN,. Cancer patient disclosure and patient-doctor communication of complementary and alternative medicine use: a systematic review. Oncologist 2012, 17: 1475–1481.

67. American Cancer Society [Internet]. Risks and side effects of dietary supplements. [cited 2019 June 27].Available from: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/complementary-and-alternative-medicine/dietary-supplements/risks-and-side-effects.html

68. De Smet PA. Health risks of herbal remedies: an update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004, 76: 1–17.

69. MacGregor G, Smith AJ, Thakker B,. Yoghurt biotherapy: contraindicated in immunosuppressed patients? Postgrad Med J 2002, 78: 366–367.

70. Mehta A, Rangarajan S, Borate U. A cautionary tale for probiotic use in hematopoietic SCT patients-Lactobacillus acidophilus sepsis in a patient with mantle cell lymphoma undergoing hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013, 48: 461–462.

71. Bello N, Winit-Watjana W, Baqir W,. Disclosure and adverse effects of complementary and alternative medicine used by hospitalized patients in the North East of England. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2012, 10: 125–135.

72. Braun, L, Cohen M. Herbs & Natural Supplements: an evidence based guide. 4th Edition ed. 2015: Elsevier Australia.

73. Rockwell S, Liu Y, Higgins SA. Alteration of the effects of cancer therapy agents on breast cancer cells by the herbal medicine black cohosh. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005, 90: 233–239.

74. Yeung KS, Gubili J, Mao JJ. Herb-Drug Interactions in Cancer Care. Oncology (Williston Park) 2018, 32: 516–520.

75. Wu JJ, Ai CZ, Liu Y,. Interactions between phytochemicals from traditional Chinese medicines and human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Curr Drug Metab 2012, 13: 599–614.

76. Mukherjee PK, Ponnusankar S, Pandit S,Botanicals as medicinal food and their effects on drug metabolizing enzymes. Food Chem Toxicol 2011, 49: 3142–3153.

77. Izzo AA, Ernst E. Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: an updated systematic review. Drugs 2009, 69:1777–1798.

78. Zhou SF. Drugs behave as substrates, inhibitors and inducers of human cytochrome P450 3A4. Curr Drug Metab 2008, 9: 310–322

79. Di Francia R, Rainone A, De Monaco A,Pharmacogenomics of Cytochrome P450 Family enzymes: implications for drug–drug interaction in anticancer therapy. WCRJ 2015, 2: e483.

80. Elmer GW, Lafferty WE, Tyree PT,. Potential interactions between complementary/alternative products and conventional medicines in a Medicare population. Ann Pharmacother 2007, 41: 1617-1624.

81. Loquai C, Schmidtmann I, Garzarolli M,Interactions from complementary and alternative medicine in patients with melanoma. Melanoma Res 2017, 27: 238–242.

82. Tascilar M, de Jong FA, Verweij J,. Complementary and alternative medicine during cancer treatment: beyond innocence. Oncologist 2006, 11: 732–741.

83. Alsanad SM, Williamson EM, Howard RL. Cancer patients at risk of herb/food supplement-drug interactions: a systematic review. Phytother Res 2014, 28: 1749–1755.

84. Vickers A, Zollman C, Lee R. Herbal medicine. West J Med 2001, 175: 125–128.

85. Spinella M. The importance of pharmacological synergy in psychoactive herbal medicines. Altern Med Rev 2002, 7: 130–137.

86. Meijerman I, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. Herb-drug interactions in oncology: focus on mechanisms of induction. Oncologist 2006, 11: 742–752.

87. McLay JS, Stewart D, George J,. Complementary and alternative medicines use by Scottish women with breast cancer. What, why and the potential for drug interactions? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012, 68: 811–819.

88. Neuhouser ML, Smith AW, George SM,. Use of complementary and alternative medicine and breast cancer survival in the Health, Eating, Activity, and Lifestyle Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016, 160: 539–546.

89. Ashikaga T, Bosompra K, O'Brien P,. Use of complimentary andbalternative medicine by breast cancer patients: prevalence, patterns and communication with physicians. Support Care Cancer 2002, 10: 542–548.

90. Chen Z, Gu K, Zheng Y,. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Chinese women with breast cancer. J Altern Complement Med 2008, 14: 1049–1055.

91. Moran MS, Ma S, Jagsi R,. A prospective, multicenter study of complementary/alternative medicine (CAM) utilization during definitive radiation for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013, 85: 40–46.

92. Yap KP, McCready DR, Fyles A,. Use of alternative therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen after surgery. Breast J 2004, 10: 481–486.

93. Saquib J, Madlensky L, Kealey S,. Classification of CAM use and its correlates in patients with early-stage breast cancer. Integr Cancer Ther 2011, 10: 138–147.

94. Tautz E, Momm F, Hasenburg A,. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in breast cancer patients and their experiences: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer 2012, 48: 3133–3139.

95. Wyatt G, Sikorskii A, Wills CE,. Complementary and alternative medicine use, spending, and quality of life in early stage breast cancer. Nurs Res 2010, 59: 58–66.

96. Shaharudin SH, Sulaiman S, Emran NA,The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Malay breast cancer survivors. Altern Ther Health Med 2011, 17: 50–56.

97. Kang E, Yang EJ, Kim SM,. Complementary and alternative medicine use and assessment of quality of life in Korean breast cancer patients: a descriptive study. Support Care Cancer 2012, 20: 461–473.

98. Sárváry A, Sárváry A. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among breast cancer patients in Hungary: A descriptive study. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2019, 35: 195–200.

99. Hwang JH, Kim WY, Ahmed M,. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by Korean Breast Cancer Women: Is It Associated with Severity of Symptoms? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015, 2015: 182475.

100. Molassiotis A, Scott JA, Kearney N,. Complementary and alternative medicine use in breast cancer patients in Europe. Support Care Cancer 2006, 14: 260–267.

101. Helyer LK, Chin S, Chui BK,. The use of complementary and alternative medicines among patients with locally advanced breast cancer--a descriptive study. BMC Cancer 2006, 6: 39.

102. Greenlee H, Neugut AI, Falci L,. Association Between Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use and Breast Cancer Chemotherapy Initiation: The Breast Cancer Quality of Care (BQUAL) Study. JAMA Oncol 2016, 2: 1170–1176.

103. Kremser T, Evans A, Moore A,. Use of complementary therapies by Australian women with breast cancer. Breast 2008, 17: 387–394.

104. Gulluoglu BM, Cingi A, Cakir T,. Patients in Northwestern Turkey Prefer Herbs as Complementary Medicine after Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Breast Care (Basel) 2008 3: 269–273.

105. Albabtain H, Alwhaibi M, Alburaikan K,. Quality of life and complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer. Saudi Pharm J 2018, 26: 416–421.

106. Kalender ME, Buyukhatipoglu H, Balakan O,. Depression, anxiety and quality of life through the use of complementary and alternative medicine among breast cancer patients in Turkey. J Cancer Res Ther 2014, 10: 962–966.

107. Abdullah AS, Lau Y, Chow LW. Pattern of alternative medicine usage among the Chinese breast cancer patients: implication for service integration. Am J Chin Med 2003, 31: 649–658.

108. Owens B, Jackson M, Berndt A. Complementary therapy used by Hispanic women during treatment for breast cancer. J Holist Nurs 2009, 27: 167–176.

109. Balneaves LG, Bottorff JL, Hislop TG,. Levels of commitment: exploring complementary therapy use by women with breast cancer. J Altern Complement Med 2006, 12: 459–466.

110. Cui Y, Shu XO, Gao Y,. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by chinese women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2004, 85: 263–270.

111. Can G, Demir M, Aydiner A. Complementary and alternative therapies used by Turkish breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Breast Care (Basel) 2012, 7: 471–475.

112. Hann D, Allen S, Ciambrone D,. Use of complementary therapies during chemotherapy: influence of patients' satisfaction with treatment decision making and the treating oncologist. Integr Cancer Ther 2006, 5: 224–231.

113. Montazeri A, Sajadian A, Ebrahimi M,. Depression and the use of complementary medicine among breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2005, 13: 339–342.

114. Rakovitch E, Pignol JP, Chartier C,. Complementary and alternative medicine use is associated with an increased perception of breast cancer risk and death. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005, 90: 139–148.

115. Shen J, Andersen R, Albert PS,. Use of complementary/alternative therapies by women with advanced-stage breast cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med 2002, 2: 8.

116. Bausell RB. Snake Oil Science: The Truth About Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Oxford University Press, New York, 2007.

117. Lete I, Allué J. The Effectiveness of Ginger in the Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting during Pregnancy and Chemotherapy. Integr Med Insights 2016, 11: 11–17.

118. Murphy RA, Mourtzakis M, Chu QS, et al. Supplementation with fish oil increases first-line chemotherapy efficacy in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:3774–80.

119. Sakamoto J, Morita S, Oba K,. Efficacy of adjuvant immunochemotherapy with polysaccharide K for patients with curatively resected colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of centrally randomized controlled clinical trials. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2006, 55: 404–411.

120. del Giglio AB, Cubero Dde I, Lerner TG,. Purified dry extract of Paullinia cupana (guaraná) (PC-18) for chemotherapy-related fatigue in patients with solid tumors: an early discontinuation study. J Diet Suppl 2013, 10: 325–334.

121. Sahebjamee M, Mansourian A, Hajimirzamohammad M,. Comparative Efficacy of Aloe vera and Benzydamine Mouthwashes on Radiation-induced Oral Mucositis: A Triple-blind, Randomised, Controlled Clinical Trial. Oral Health Prev Dent 2015, 13: 309–315.

122. Ryan JL, Heckler CE, Roscoe JA,. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces acute chemotherapy-induced nausea: a URCC CCOP study of 576 patients. Support Care Cancer 2012, 20: 1479–1489.

123. Cruz-Correa M, Shoskes DA, Sanchez P,. Combination treatment with curcumin and quercetin of adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006, 4: 1035–1038.

124. Barton DL, Liu H, Dakhil SR,. Wisconsin ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) to improve cancer-related fatigue: a randomized, double-blind trial, N07C2. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013, 105: 1230–1238.

125. Murphy RA, Mourtzakis M, Chu QS,. Nutritional intervention with fish oil provides a benefit over standard of care for weight and skeletal muscle mass in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy. Cancer 2011, 117: 1775–1782.

126. Ozkaraman A, Dügüm Ö, Özen Yılmaz H,. Aromatherapy: The Effect of Lavender on Anxiety and Sleep Quality in Patients Treated With Chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2018, 22: 203–210.

127. Khaksarian M, Behzadifar M, Behzadifar M,. The efficacy of Crocus sativus (Saffron) versus placebo and Fluoxetine in treating depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2019, 12: 297–305.

128. Pasta V, Dinicola S, Giuliani A,. A randomized trial of Boswellia in association with betaine and myo-inositol in the management of breast fibroadenomas. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2016, 20: 1860–1865.

129. Schmiech M, Lang SJ, Werner K,Comparative Analysis of Pentacyclic Triterpenic Acid Compositions in Oleogum Resins of Different Boswellia Species and Their In Vitro Cytotoxicity against Treatment-Resistant Human Breast Cancer Cells. Molecules 2019, 24(11): pii: E2153.

130. Jacobs J, Herman P, Heron K,. Homeopathy for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med 2005, 11: 21–27.

131. Heudel PE, Van Praagh-Doreau I, Duvert B,. Does a homeopathic medicine reduce hot flushes induced by adjuvant endocrine therapy in localized breast cancer patients? A multicenter randomized placebo-controlled phase III trial. Support Care Cancer. 2019, 27: 1879–1889.

132. Carlson LE, Doll R, Stephen J,. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness based cancer recovery versus supportive expressive group therapy for distressed survivors of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013, 31: 3119–3126.

133. Binns-Turner PG, Wilson LL, Pryor ER,. Perioperative musicand its effects on anxiety, hemodynamics, and pain in women undergoing mastectomy. AANA Journal 2011, 79: S21–S27.

134. Taso CJ, Lin HS, Lin WL,. The effect of yoga exercise on improving depression, anxiety, and fatigue in women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Res 2014, 22:155–164.

135. Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B,. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2012, 118: 3766–3775.

136. Bao T, Cai L, Snyder C,. Patient reported outcomes in women with breast cancer enrolled in a dual-center, double-blind, randomized controlled trial assessing the effect of acupuncture in reducing aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal symptoms. Cancer 2014, 120: 381–389.

137. Molassiotis A, Bardy J, Finnegan-John J,. Acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30: 4470–4476.

138. Mao JJ, Xie SX, Farrar JT,. A randomised trial of electro-acupuncture for arthralgia related to aromatase inhibitor use. Eur J Cancer 2014, 50: 267–276.

139. Henderson VP, Massion AO, Clemow L,. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for women with early stage breast cancer receiving radiotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther 2013, 12: 404–413.

140. Billhult A, Bergbom I, Stener-Victorin E. Massage relieves nausea in women with breast cancer who are undergoing chemotherapy. J Altern Complement Med 2007, 13: 53–57.

141. Nahin RL, Straus SE. Research into complementary and alternative medicine: problems and potential. BMJ 2001, 322: 161–164.

142. Mason S, Tovey P, Long AF. Evaluating complementary medicine: methodological challenges of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2002, 325: 832–834.

143. Miller FG, Emanuel EJ, Rosenstein DL,Ethical issues concerning research in complementary and alternative medicine. JAMA 2004, 291: 599–604.

144. Fan Y, Zhang H, Yang G,. China's cancer patients'perceptions, attitudes and participation in clinical trials of complementary and alternative medicine:A multi-center cross-sectional study. Eur J Integ Med 2018, 19: 115–120.

:

This work was supported by grant from the Serbian Ministry of Science and Technological Development (OI 175 014).

:

CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; NCCIH, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

:

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

:

Milena Jurisevic, Sergey Bolevich. Complementary and alternative medicine applications in cancer medicine. Traditional Medicine Research, 2020, 5 (1): 7–21.

:Cui-Hong Zhu, Nuo-Xi Pi.

:17 June 2019,

30 July 2019,

: 9 August 2019.

Milena Jurisevic, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Svetozara Markovica 69, Kragujevac 34000, Serbia. E-mail: milena.jurisevic13@gmail.com.

Traditional Medicine Research2020年1期

Traditional Medicine Research2020年1期

- Traditional Medicine Research的其它文章

- The role of acidic microenvironment in the tumor aggressive phenotypes and the treatment

- Astragalus injection as an adjuvant treatment for colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis

- Clinical distribution and molecular profiling on postoperative colorectal cancer patients with different traditional Chinese medicine syndromes

- Editor-in-Chief of Special Issue on Integrative Oncology

- Application of nanoparticles in the early diagnosis and treatment of tumors: current status and progress

- Research hotspot and frontier progress of cancer under the background of precision medicine