Plugged In

By Yuan Yuan

When people fabricate stories about a person, especially a popular star, and then spread them online, they cannot hide behind screens. They can easily be traced and taken to court.

A report released on December 19, 2019 by the Beijing Internet Court showed that about 28 percent, or 41,948, of Internetrelated cases fi led from January to November of the same year were related to reputation infringement.

The defendants, mostly aged 19 to 30, were taken to court for the damaging words or falsified information they used to insult some celebrities, while supporting their own idols online.

“We suggest government departments, social associations and Internet enterprises cooperate with us to help regulate young peoples behaviors online to keep cyberspace in better order,” said Zhang Wen, the courts president.

Internet connection

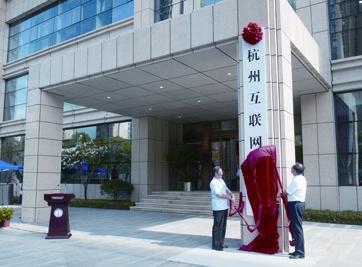

Founded on September 9, 2018, the Beijing Internet Court is Chinas second Internet court after the opening of the first in Hangzhou, capital city of Zhejiang Province in east China, in August 2017. It is followed by a third in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province in south China, on September 28, 2018.

“With the fast growth of the Internet and technologies, a large number of disputes happen online, which have brought challenges and opportunities to our courts, pushing us to fi nd new ways to hear these cases more effi ciently and effectively,” said Li Shaoping, Vice President of the Supreme Peoples Court (SPC).

Efforts to establish an Internet judiciary began in October 2016, when the SPC initiated an online mediation platform to handle Internet-related issues before and during litigation as well as judicial confi rmation.

The courts mainly cover Internet and intellectual property (IP) rights cases, including disputes involving online loans, sales contracts and copyright issues. All legal procedures, including case fi ling, trial and ruling, are conducted online and rulings are sent via telephone, e-mail, WeChat and other online methods.

On December 4, 2019, a white paper titled Chinese Courts and Internet Judiciary was released, summarizing the courtsachievements in improving judicial effi ciency through the Internet. It is the first white paper on the Internet judiciary of Chinese courts as well as the first on judicial innovation and development concerning the Internet in the world.

The paper stated that the three courts had heard a total of 118,764 Internetrelated disputes as of October 31, 2019, and had reduced the time needed to handle cases by approximately 50 percent. It took the courts an average of 45 minutes to fi nish an online hearing and 38 days to conclude a case.

Among the recorded disputes, more than 88,000 had been concluded.

Up to 98 percent of the parties had accepted first-instance judgments without appeal.

“Chinese courts have intensified the crackdown on crimes, such as operating online casinos, Internet fraud, theft of digital assets and infringements of personal information, and have managed to guarantee the safety and order of cyberspace,” said the white paper.

Li said the three Internet courts have accumulated experiences that can be reproduced and promoted in the fields of case handling, online platform development, litigation guidelines, technology application and Internet governance.

Making a case

“The Internet is not a lawless place,” said Zhu Xiaolei, a Beijing-based lawyer who has handled many Internet-related disputes.“With the burgeoning of online business and various online social network apps, the number of these cases has increased sharply.”

In 2018, ByteDance, the company owning Douyin, a popular video-sharing app known as TikTok overseas, claimed that one of its videos, lasting only 13 seconds, had been downloaded and broadcast on another online platform. The company charged that this had infringed on its online copyright.

“It was not an easy online copyright infringement case, like those we had handled before involving photo and fi lm IP rights,”said Zhu Ge, a Beijing Internet Court judge.

The question of whether content posted on short video apps could be identifi ed and protected as a traditional online work was the issue and how to judge the dispute without impinging on the healthy development of the short video industry was a new challenge for the court.

In the end, the court ruled that Douyin short videos should receive equal IP protection, and clarified that “online works”are those with original contents.

Moreover, new technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain, have gradually been adopted in these courts as well.

In the Beijing Internet Court, a system based on blockchain technology has enabled automatic case filing in the enforcement of a mediation agreement.

With a click, the enforcement case is automatically filed when the respondent fails to pay the damages in the mediation agreement.

“Applying smart contract technology is expected to promote deeper integration of data sharing on the blockchain and the judicial information system,” said Zhang.

“Internet courts are online 24 hours a day,” Du Qian, President of the Hangzhou Internet Court, said. To solve problems such as the litigants being in different time zones, the Hangzhou court launched a hearing model that allows litigants in a case to log on at different times to complete the hearing.

The court also released 5G virtual reality glasses, which makes litigants feel like they are in a real courtroom. It also has an AI judge assistant that can answer a litigants questions and offer help during the procedure.

“The Internet courts have made judicial enforcement more intelligent and transparent, and have improved the effi ciency and precision of judicial practices,” Du said.