阿根廷文化景观研究、项目和表现

著:(阿根廷/西班牙)梅丽莎·佩索阿 (西班牙)宝拉·奥尔杜尼亚 (西班牙)华金·萨巴特 译:林静静 校:王勤

1 文化景观的术语简析

“景观”一词(英语landscape,西班牙语paisaje)的诞生与人类如何看待特定空间有着紧密的联系。其词源与撒克逊语的“landschaft”或源自拉丁语“pagus”的西班牙语Payés相关。拉美景观是19世纪初亚历山大·冯·洪堡在其地理学著作中用来传播这一名词的关键元素,他将这些景象作为一种审美观带到了欧洲,尤其是代表了崇高之美的观念。

1 阿根廷科尔多瓦省圣卡洛斯矿区的河流与道路之间的情况简图Sketch of the situation between rivers and road of San Carlos Minas,Córdoba Province,Argentina

2 七色山The Seven Colours Hill

这种与特定自然地貌相关,强调自然与文化分离的观点持续了数十年,是启蒙运动后典型的西方世界观,并且被工业革命所强化。在这种情况下,自然被视为物体,是人们从中获得资源和从事活动的地方。

为了建立人与自然之间的直接关系,伯克利学院的创始人,美国地理学家卡尔·绍尔使用了文化景观的概念。根据他的设想,一个脱离自然景观之外的文化群体创造了文化景观,即文化作为代理人,自然区域作为媒介,其结果就将是文化景观。因此,在一种确定文化的影响下,景观可以发展和转变[1]。

阿基洛强化了这一设想:“或许如此理解更有吸引力,文化景观的意念并非指向某种特殊景观,因为各种各样的也都是景观,而是指人们在与自然经年累月的互动中看待景观的某种特殊的方式。[2]”确实,在绍尔提出自己的概念解释已近一个世纪的今天,文化景观这个名词包含着一定的冗余,因为就我们当下的定义而言,每个景观都是具有文化性的。出现这种赘言的原因可能是在西方世界现代化初期,景观的归化常常将景观与物质环境混为一谈。这就引发一种为指代环境的文化性建设而谈论文化景观的需要[3]。

联合国教科文组织吸收了这一概念,并在1992年,由世界遗产委员会将“文化景观”作为类别纳入“操作指南”之中。他们将文化景观定义为“自然与人类的联合作品”①。然而,教科文组织似乎更专注于管理、保护和政治方面,而非出自学术和设计上的兴趣[4]。而当他们意识到所需要的“并非只是令这样的空间保存下来的人工手段,而是在不破坏其形式的前提和重新适配其形态和生活功能的明确目标下,活化其功能的措施”时,其概念应用上的缺陷更加明显[5]。

2 从概念到项目

文化景观项目不仅关注处于生存危机中的景观的保护,还关注景观从社会、政治和经济角度来看所具有的价值的持久性。尽管文化景观确实是增强当地经济的潜在力量,但不应只着眼于吸引游客,首先应创建一个系统来维护景观和行为者的关系。

通过这种方式,设计师的作用是在这种景观的地理、历史和进化中找到那些可以成为与当地社会特性相关的一种替代性发展结构要素的操作规则。

为了研究地域的历史,有必要统计其上已经和正在发生的操作。从多学科的角度来看,这是一项涉及历史学家、地理学家、建筑师、人类学家、社会学家等多方参与完成的任务。毫无疑问,这项研究需要准备详细描述在该地域上已经或正在发生的过程和动态的资料,其形式包括书面描述或分析以及项目提案。

这个构想让我们得以将分析融入项目和行动调查。伊萨盖瑞(Eizaguirre)[6]将地域分析置于地理学和城市规划之间的汇合处,也就是在描述和定位之间阐明可替代性方案就存在于其特性之中。早先,帕特里克·格迪斯(Patrick Geddes)爵士在维达尔·白兰士(Paul Vidal de la Blache)或埃利塞·何克律(Élisée Reclús)的观点基础上发展而来的区域(region)理念中也提出,“随着研究的推进,我们开始通过延续至今的时间与空间感受到了所在区域的舒适感。从此,无论过去时,还是现在时的东西都只能被引向某种可能性。我们研究这些事物的形成也就是在探讨其进一步的转化方式,也就是其未来的可能性。可见,我们的研究具有超越纯粹科学兴趣的实际意义。总之,研究是在为计划做准备……”[7]。

基于这个观点,研究和行动之间的关系恰恰是我们的兴趣所在。从这个意义上说,在20世纪70年代的美国国家公园管理局的工作中,在西班牙加泰罗尼亚地区[8]和伊比利亚半岛北部地区[9]的研究中,或在特内里费的岛屿秩序计划[10]中都有明确的先例。具有更大利益和创新特征的计划和项目如今也都在优先考虑与遗产观念关联的自然与文化之间的关系。在这一背景下,“文化景观”类别可以成为一个具有重要意义的规划工具,这是因为“它们构成了对记忆和地域特性的,越来越丰富的表达”[11]。

3 绘图作为解释、叙述和项目工具

对于地域综合和针对文化景观的干预尤其需要学科革新方面的努力,这也意味着一种在表现方面上的创造性工作。在有些面积巨大的项目中,我们想要认知的痕迹十分微弱或者分散,有时这些地域又远离通常的工作范围。面对这些困难,一些研究和项目着力发展了在地域调查构建中的精确性和创造性。

3 乌玛瓦卡峡谷市场Market in Quebrada de Humahuaca

当从城市规划专业角度研究和规划文化景观时,绘图就成为一个基本工具。表现作为一种项目工具,不仅从沟通的角度不可或缺,更对解读地域至关重要[12-13]。然而,并非所有地域都有更新的地图,也没有像谷歌地球和地理信息系统这种典型的共享知识图像。即使现有的城市地图比较完整,也有更新,但随着我们在各个城市间的移动,图示表达的数量、质量和时效性也会淡化。

由于通常在大量地域和城市研究,特别是拉丁美洲的案例研究中都面临着历史上和当前的地图学缺失,以及没有通用精确摄影测量飞行器的问题,我们有时就不得不艰辛地手绘一个地域。这项需要精确、严谨的意念来完成的工作是一种非凡的知识发生器。对这些情况的直接了解使我们能够就地域的认知与干预讨论图像表达所能提供的其他可能性,也就是如何建立解释性阅读。

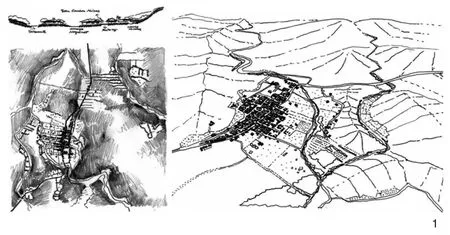

为了说明这个想法,我们将揭示费尔南多·迪亚兹在表现阿根廷科尔多瓦省西端德拉斯拉斯艾拉区域土地占用逻辑时所做出的努力[14]。这是一片几乎没有政府管理和研究人员涉足的地区,也没有图像或编年史记载。其独特的表现致力于通过识别可阐明未来管理标准的不同景观单元和元素来揭示地域建设的文化与景观资源。内容包括精美总图、罕见的建筑手记和地域故事以及能让我们回想起17—18世纪城市的鸟瞰图(图1)。

这些地域图解从不同的角度表明,图形表达不仅仅伴随着论证或解释,其本身也因为有助于揭示传统书面文件所忽略的信息和问题而成为构建知识的资源。

4 阿根廷的文化景观

由于其独特性和多样性,拉丁美洲文化景观提供了一个极具吸引力的项目实验室。其最引人注目的特征就是巨大的尺度。例如,印加步道就从阿根廷到哥伦比亚穿越了几个国家。另一个值得注意的方面是繁茂的自然掩盖了过去文明的痕迹。甘蔗、咖啡、龙舌兰酒、牲畜、矿藏等多种多样的资源导致了新建设类型的出现—如耶稣会牧场、榨糖小镇、咖啡种植园—当然也导致了精巧用具和复杂机械的出现。

但是,文化资源的管理也是一种挑战,特别是考虑到在某些制度背景薄弱的案例中[15],以及受制于旅游或自然资源开发等经济活动的压力,环境风险和各种土地所有权问题的情况下。

从这里我们将着重阐释这些概念在阿根廷的情况,这将有助于说明针对这些方面正在这片土地上实施的一些策略。

在阿根廷,得益于仍然居住在这片土地上的土著部落,我们发现了千年文化遗迹和延续至今的祖先庆祝活动,这也是一段关于西班牙征服者的到来,国民大会的成立以及之后国家独立的历史。我们还有可能找到与农业生产有关的历史印记和传统,历史城市和与栖居文化相关的自然美景,以及探戈、足球文化和各种公民及宗教节日等这些极具价值的非物质遗产。

正如我们预告的那样,我们将利用2个关于文化景观的实施项目来提供有关这些想法的实际情形。我们选择了2个在地域尺度上很有意思的案例。考虑到景点间的距离、可达性和该地区典型文化景观的维度,我们认为这种尺度是最难处理的。

4.1 乌玛瓦卡峡谷

乌玛瓦卡峡谷(Huamhuaca’s Gorge)是沿胡胡伊大河谷(位于阿根廷胡胡伊省)的一条自然走廊,延伸约155km,两侧是近4 000m的山脉(图2)。从历史上看,它起到了连接拉普拉塔河地区与从玻利维亚到秘鲁的前殖民地北部的作用,因而也呈现出丰富的考古遗迹。约有3万居民人口主要居住在通巴亚、蒂尔卡拉和乌玛瓦卡等重要地区。

那里的人口总体状况非常不稳定,游客数量的增加,正如世界上其他许多地方那样,带来了意想不到的负面影响。在各种互联网论坛上,人们斥责那些来侵占土地的外国人导致原住民被驱逐的现象,以及那些不顾本地居民住房条件恶劣的实际情况仍在大肆修建酒店的行为所带来的不公现象或者日益增加的环境不安全感。

通过“文化景观作为地方发展的资源”的ALFA项目,加泰罗尼亚理工大学(UPC)与布宜诺斯艾利斯大学(UBA)之间的合作计划于2009年开始启动。该计划包括通过奖学金获得者和教授间的交流互换建立一个课程网络,允许在阿根廷的国土研究中针对地理、经济和社会空间的维度添加地域的形态学外观。

该项目分析了乌玛瓦卡峡谷地区于2003年被纳入教科文组织世界遗产名录中的文化景观类别之后,遗产化和旅游化带来的变化②。这一事件使迄今为止还只有当地发展动力的地区在本土与全球级别之间的分歧一目了然。在这种极端脆弱的社会背景下,任何干预都可能被理解成既是一个机会,也是一种威胁。

于是在入选宣布几年之后,实际影响开始明晰:旅游带来的好处没有回馈给当地人,旅游业只在最容易到达的地方发展,而考古遗址也显示出退化迹象。另一方面,农业活动处于深度危机之中,采矿活动对定居人口造成严重影响和排斥。居住区的建设不再遵守任何以往的组织,住宅以通用的布置方式被建造在周边地区。另外,行政管理方面也表现出一定的技术弱点,地方政府和社区之间很少或根本没有沟通。

出于所有这些原因,我们如此需要这样一个能够在本地居民和运作景观的代理人都认同的情况下调动所有力量的项目。这在制度环境薄弱的背景下,显得更为重要。于是,启动了一系列研究,并持续运行至今。其中第一个提案便是建立一套涵盖整体地域的各个方面和分体的连贯叙述[16]。为了做到这一点,我们确定了以下不同的部分:格兰德河及其流域线性构造影响下的溪流地质形成;布卡拉(pucarás),避开主流域而在安全地带建立的第一批定居点;皇家之路(Royal Road)在印加古道布局之上的建造以及形成文化交流环路的驿站系统;促进人口聚居中心发展的农业活动,评价它们与自然环境的互动;与合作社的存在相关的水利磨坊的应用;铁路的建立、高峰与衰落;与自然节气密切相关的节日庆典等。相应的信息工作则开始于对人在不同尺度上与地域关联的理解上,并反向在各种尺度的制图表达中体现出来。

4 潘帕斯平原The pampas plain

5 潘帕斯的典型膳食:烤肉Typical meal of the pampas:roast meat

特别开展的研究还包括从地理学角度出发的地方与全球关系、城市角度下的新住区建设、场所的历史再现和形象构建、遗产建筑分析、影响知名旅游城镇的经济动态和该地区的社会经济数据等[17](图3)。

虽然以上研究都是大维度的学术性工作,但其导则不仅被用于培育和丰富当地的管理工作,而且被纳入了“国土战略计划”,最终将有助于修订该地段在某些具体方面的管理计划。

除了这些结果,我们还要强调的是绘图在这种研究中的重要性。这些地域缺乏良好的地理制图,只是近年来才有了GIS数据。因此,每个研究领域都需要在意向性制图的构建方面开展大量高强度工作[18]。

最近有几个基于各种尺度图形工作的博士论文具有建立新知识的能力。在城市层面,它展示了“历史中心”在从居住到旅游装备的路线上是如何转变的,以及新旅游设施带来的景观变化[19]。在更广阔的地域范围内,由于“中心”运作模式而被挤出的人们的新定居点也被标识了出来[19-20]。在更广泛的层面上,这些研究分析了2003年教科文组织指定的资产划界标准以及选择和评估的冲突。由此制作出来的一系列图纸揭示了有关该地区基础设施工程、地形和传承资源之间利害关系的一些逻辑。

毫无疑问,这项研究应该继续深化经济支持或培训措施,以增加创造就业的替代性方案,从而保持一个不仅仅包括简单的自然或城市住区的景观。诸如获得社区土地所有权,灌溉用水的可用性,加强对小生产者的营销、财务和技术援助,整合生产链或建立一个综合的生产信息系统等问题,都对这一地域的妥善管理至关重要。

4.2 高乔人之路

潘帕斯平原地区面积约50万km2(图4)。原本缺乏树木,西班牙征服者将牛群带到这片土地上,大量繁衍生息,如今已经和麦子、大豆等谷物种植一起成为该地区的特色产业。然而,这种绝美的景观对于当地居民来说只是日常景观,而且由于其延展区辽阔和远离城镇而难以被认知。

高乔人③之路的构想基于为潘帕斯平原景观赋予价值,保护沿海生态系统,并为布宜诺斯艾利斯人民提供传统海滩旅游活动以外的活动等需求。该项目启动于1994年,由CEPA基金会倡导,旨在恢复高乔人文化,并将其作为创造可持续和包容性文化旅游的手段(图5)。这个系统将结合少数幸存在该地区的土著文化要素、高乔人文化、欧洲移民、农业出口经济、本土自然生态系统以及当前的海滩旅游文化[21]。

潘帕斯地区有大量的自然保护区。其中一些是联合国教科文组织认定的生物圈保护区,如南部沿海公园或者奇基塔大西洋公园及潟湖,还有一些是省级或国家级的保护区,如桑博罗姆湾、阿霍河、萨拉达格兰德潟湖和梅达诺斯角。

这个地域所面临的最大挑战之一就是其巨大的尺度。在考虑不同地方的可达性以及它们之间的连接时会出现的多种困难,但这一问题在有限的领域内更容易解决,鉴于此,我们可以将项目区域限定在400km×200km的矩形框中。通过这种方式,该系统由连接布宜诺斯艾利斯与普拉塔海地区的快速通道(2号高速公路,大约4.5h车程)和沿海岸线延续老皇家之路的较慢行道路(省际11号路)构成。而这些道路又依次通过地方道路相互连接。

研究者在分析了这一地域的有形和无形价值之后,决定构建以生态博物馆或文化旅游景地网络为基础的项目提案,类似于中小型企业模式运作,由本地居民(如商人、生产者、教育者等)管理。通过这种方式,这一项目旨在推进社会组织的形成过程;并且,因为项目将会涉及大量针对该地区的科研工作,以及地方性或国际间合作,所以也将会激励农村生产者、商家、旅游代理人、本地协会和科学组织等各界人士的广泛参与。

最终,基于3种点位的生态博物馆网络于2001年建成。天线是指那些具有最大容量和信息交流的站点,比如大城市;节点是所有被选作有价值遗产的自然和文化资源;最后,门户是高乔人之路各个路线的出、入口以及综合服务区。反向鉴于这个范围的尺度,4条可以独立进行或相互连接的主题路线被建立了起来。

在拉普拉河的脉络上,有可能找到河床文化的风景和习俗。这一地域形成于西班牙殖民末期(18世纪),拥有在布宜诺斯艾利斯以南第一批修建的马车道、牧场、村庄和堡垒。

潟湖与海滩的脉络显示出了大平原的广袤,它与萨拉多河盆地潟湖与河道的交织关系,以及蜿蜒于沿海潟湖、巨大的沙丘和大量细沙滩间,最终流入大西洋的自然排水系统。省际铁路(现在已停运)在周围安置了几十个小站和乡村小镇,如今都已成为丰富遗产的一部分。

历史城镇的脉络是这个网络中最显著的生态博物馆,它们的空间和文化博物馆的质量反映出了由所谓“征服沙漠”运动前沿和阿根廷政权组织从1810年出现至1852年确立期间联邦派与集权派之间的征战所造就的人迹和地貌状况。

海洋和山脉的脉络是在群山和草地间发展起来的,突出了农业实践和阿根廷最富饶地区之一的自然之美。拉普拉塔海和巴尔卡塞地区的城市是与该地区旅游业已有百年传统的乡村环境融为一体的重要城市定居点。

考虑到项目的管理,需要重点强调生态博物馆在项目传播中的作用,这些生态博物馆长期处于监测之中,以保持网络的质量。同样,交流策略和定期工作营对于维持传统活动的重要性也应被重视。不过,由于没有外来投资,该项目的资金仍然需要依赖旅游业。

2006年,高乔人之路在可持续旅游的策略性联邦计划中被官方确认为布宜诺斯艾利斯省的优先走廊。自该项目开始以来,特别是在最近几年,该地区的旅游活动有所增加。然而,近年来生态博物馆虽然各个都在单独运作,但网络的效果却不尽人意。可以肯定的是,PFETS的修订(尚未实施)将能够支持重要联结工作的重建,并提供必要的资金。

5 结论

与景观及其保护相关的干预已证明,拉丁美洲,特别是阿根廷有着非常丰饶的环境。我们想要首先强调研究的计划方面及其重要的跨学科成分。从建筑和城市规划的特定领域,意向性阅读的设想被提议为寻找项目工具的强大方法,这是因为尽管其他社会、经济、政治方面的变量确实都在对该地域产生干预,但是对这些现象的资料性转译仍然是值得推荐的。

至于结果,我们认为仍然要面对几个挑战。一方面,尽管这两个案例已被纳入国家旅游开发计划,但这类项目仍存在持续的资金问题。而且,除了旅游角度之外,其他诸如生产或环境的角度也应该被考虑。此外,正如我们前文提到的那样,被考量地域的不同点位之间的距离和联系问题也就是可达性问题,是这类举措能否取得成功的关键。

已经呈现的项目都有一个统一的元素:对于一定空间模式的理解将可能成为一个项目有益于该景观的指导。意向性解读的努力是我们在本文中综合出来的关键工具。这是一种对建立更加多样化的环境,并突出其特征,同时为地方发展提供替代性方案的实用方法。这些举措取得成功的关键因素在于当地居民,因为他们的认同表明了对景观的兴趣,并会要求采取行动来保护他们的遗产。这也与干预这些景观的另一个好处有关:它们的教育功能,或者说讲述允许读者自由解释的故事的能力有助于长期维护这类遗产。

讲故事的重要性不仅限于分析和解释的目的,也要对干预该领域的人有用。要构建这个故事,就有必要精心铺陈一个手稿。这不仅意味着对于现在或过去存在的表现,而且还要有助于建立和传递想法或解释,因为没有任何表现是完全客观的。正如马努埃尔·德·索拉·莫拉莱斯所说:“绘图是在选择,选择是在解释,解释是在提议,[8]”创造性的成分会使这3个过程均具特色。

注释:

① 在1992年12月的第十六届会议上,世界遗产委员会通过了文化景观的三大分类别(UNESCO 1992:54-55),并将其纳入世界遗产名录的“操作指南”(UNESCO 1996:10-12,35~42段)。“操作指南”中第36~38段对文化景观提供了一些定义(更多详情:http://whc.unesco.org/archive/gloss96.htm)。

② 引自教科文组织网站的官方文件:https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/1116.pdf。

③ 高乔人是一类牧牛人,在马背上完成大部分工作。

④ 图1引自DíazTerreno,2013;图2引自https://medium.com

(编辑/刘玉霞)

1 A glance at the term cultural landscape

The birth of the term landscape (or paisaje,in Spanish) is indefectibly linked to how the man looks to a specific space.Its origin is linked to the Saxon term landschaft or to payés,which derives from the Latin pagus.Latin American landscapes were a key element on the propagation of the term,due to the work of A.Humboldt,who at the beginning of 19th century brought these images as an aesthetic spectacle to Europe.In this idea,the notion of sublime is especially relevant.

This view persisted for decades and was related to the nature of a particular territory,emphasized the separation between nature and culture,a characteristic of the western world after the Enlightenment,and stressed by the Industrial Revolution.Under these circumstances,nature was viewed as an object,a place from which to get resources and a support for activities.

In order to incorporate the man in direct relationship with nature,the American geographer Carl Sauer,founder of the School of Berkley,uses the concept of cultural landscape.According to his ideas,the cultural landscape is created by a cultural group out of a natural landscape,and therefore,the culture would be the agent,the natural area the medium,and the result would be the cultural landscape.Hence,under the influence of a determined culture,the landscape can be developed and transformed[1].

Aguiló reinforces this idea:“it seems more attractive to consider that the idea of cultural landscape should not be applied to a special kind of landscape,because all of them are landscapes,but to a special way of seeing the landscape which emphasizes the interaction between man and nature through time.[2]” It is true that today,almost a century after the word of Sauer,the term cultural landscape entails a certain redundancy,because today we understand that every landscape is cultural,by definition.The reason for this tautology could be that the naturalization of the landscape that took place in the beginning of Modernity in the western world,often confused the term landscape with the physical environment.This provokes a need to speak about cultural landscape in order to refer to the cultural construction of the environment[3].

The UNESCO went back to the concept and in 1992 the Committee of World heritage included the category “cultural landscape” in its Operational Guidelines.They define the cultural landscape as a“combined works of nature and of man”①.However,the UNESCO seems to have a preoccupation more focused on the administrative,preserving and political aspects than on the academic and designing interest[4].This becomes more visible when they recognize the need of “… measures which not tend to an artificial survival of this space,but to its functional vitalization without deteriorating the forms,with a clear objective of readapting its morphology and living functions”[5].

2 From the concept to the project

The project of cultural landscape is therefore addressed focusing not only on the conservation of the landscape in question but also on the durability of those values over time from the social,political and economic point of view.While it is true that cultural landscapes are potential reinforces of the local economy,they should not only be focused on attracting tourists,but above all,on creating a system to maintain that landscape and the relationship with its actors.

In this way,the role of the designers is to find in that landscape –in their geography,history and evolution–,the rules of operation that can be the structuring element of an alternative development in relation to the identity of the local society.

To work on the history of the territory,it is necessary to count the operations that have taken place and take place on it,a task that would be desirable to approach from a multidisciplinary point of view,involving historians,geographers,architects,anthropologists,sociologists,among others.This research undoubtedly requires the preparation of a careful description of the processes and dynamics that have taken place or are taking place on this territory.The compilation of these material footprints in the form of a description or analysis,contains within itself a project proposal.

This idea gives us a synthesis that unites the analytical with the project,the investigation for the action.Eizaguirre[6]situates the analysis of the territory at the confluence between geography and urban planning,that is,between description and proposition,stating that in its identity is its alternative.Something that Patrick Geddes already advanced,long ago,from a vision linked to the idea of region in line with the ideas of Paul Vidal de la Blache or Élisée Reclús:

“As our research develops,we begin to feel comfortable in our region,through their time and space until today.From here,the past and the present can only be opened to the possible.For our inquiry of such things as they are-that is,as they have become-must always suggest ideas concerning their further transformation,that is,their future possibilities.In this way it can be seen that our research has a practical interest that goes beyond its purely scientific interest.In a word,the research prepares the plan…[7]”

In this position,between research and action is that our interest is placed.In this sense,there are clear antecedents in the works of the American National Park Service of the 1970s,and in Spain,in the study of the Catalan regions[8],of the North of the Iberian Peninsula[9],or in the Insular Territorial Plan of Tenerife[10].The plans and projects of greater interest and innovative nature now prioritize the relationship between nature and culture,synthesized in the idea of heritage.In this context,the category of “cultural landscapes” can become a planning instrument of great relevance because“they constitute the expression of memory,of the identity of a territory,which can be enriched successively.[11]”

3 Drawing as an interpretative,narrative and project tool

Interventions in the territory in general and in cultural landscapes in particular require a disciplinary renovation effort and this implies a creative work on representation.In several occasions the area of the project is vast,the traces that we want to recognize are weak or disperse,sometimes these territories are far away from the regularly represented universe.To face these difficulties,some investigations and projects develop precision and creativity in the construction of territorial surveys.

When facing the study and project of a cultural landscape from the urban discipline,drawing becomes a fundamental tool.Representation is important as a project tool,not only from the communication point of view but fundamentally for the interpretation of the territory[12-13].However,not all territories have updated cartography,nor is the illustration of total knowledge,typical of Google Earth and geographic information systems.Even if the available urban cartography is something more complete and updated,as we move away from the cities,the quantity,quality and timeliness of the representations is diluted.

The scarcity of historical and current cartography,which usually faces so many studies of territories and cities—and specially Latin-American cases—and the lack of a common precise photogrammetric plane,sometimes leads to manually approaching the effort of painstakingly drawing the territory.This work,done with precise intention and rigor,it is an extraordinary generator of knowledge.The direct knowledge of many of these situations allow us to discuss the alternatives that representation offers,for recognition and intervention in the territory,that is,how to approach the construction of interpretative readings.

To illustrate this idea,we expose the efforts of Fernando Díaz to show us the logics of occupation of the territory of Traslasierra,western end of the province of Córdoba in Argentina[14].It is an area that has hardly been attended by the administration or even researchers,of which there are no portraits or chronicles.And yet the unique representation is committed to revealing the cultural and landscape resources that inform the construction of the territory,through the identification of different landscape units and elements that can shed light on future management criteria.And it is done with an exquisite drawing,building calligraphies and stories of a territory until the orphan date of them,bird'seye views that recall those that we mentioned for the cities of the XVII-XVIII century (Fig.1).

From very different perspectives,drawn territories show that graphic representations do not simply accompany argumentations or interpretations,but are,in themselves,a resource for the construction of knowledge,because they help to reveal information and questions that traditional written documents ignore.

4 Cultural landscapes in Argentina

Latin American cultural landscapes offer a laboratory of projects of enormous interest because of their singularities and variety.The most striking is its enormous size.For example the Inca Trail crosses several countries,from Argentina to Colombia.Another remarkable aspect is the exuberance of nature,which masks the traces of past civilizations.The resources are diverse:sugarcane,coffee,tequila,livestock,mining,etc.This supposes the emergence of new constructive typologies—such as the Jesuit estancias,the engenhos or sugar towns,the coffee plantations–and also to ingenious utensils and sophisticated machineries.

But the management of cultural resources also poses a challenge,especially considering that in some cases these are weak institutional contexts[15]and are subject to pressures not only of economic activities such as tourism or exploitation of natural resources,but also environmental risks and various problems related to land ownership.

From here we will focus on the interpretation of these concepts in Argentina,which will serve to illustrate some of the strategies that are being carried out in the continent,where there is much work done in these aspects.

In Argentina we find vestiges of millenarian cultures,ancestral celebrations that have lasted thanks to the aboriginal tribes that still inhabit this territory,a past related to the arrival of the Spanish conquerors,the establishment of missions and the subsequent Independence.It is also possible to find historical traces,traditions related to agricultural production,historical cities and natural beauty landscapes linked to the cultures that inhabit it.And it also has an intangible heritage of great value,among which we can mention the tango,the culture around football and a variety of civic and religious festivities.

As we have anticipated,we will use two work projects on cultural landscape to offer a practical vision of these ideas.We selected two cases that are interesting at the territorial scale.We think this scale is the most difficult to face,concerning the distances between the point of interest and the accessibility and dimensions of the typical cultural landscapes of the region.

4.1 La Quebrada de Humahuaca

The Quebrada de Humahuaca (Huamhuaca’s Gorge) is a natural corridor formed along the valley of the Rio Grande de Jujuy (in Jujuy Province,Argentina),which extends for about 155 km,flanked by mountain ranges of almost 4,000 meters in height (Fig.2).Historically,it functioned as the connection of the Rio de la Plata area with the northern part of the former colonial lands,from Bolivia to Peru and therefore presents abundant archaeological remains.Population—around 30,000 inhabitants—live mostly in important areas such as Tumbayá,Tilcara or Humahuaca.

The general conditions of the population are very precarious and the growing influx of tourists supposes,as in so many other places in the world,unanticipated and perverse effects.In various Internet forums population denounce foreigners who usurp the land;the expulsion of aboriginal communities;a growing insecurity or the construction of hotels while residents live in houses without conditions.

Through the ALFA program “Cultural landscapes as a resource for local development”an inter-university cooperation program between the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC) and the University of Buenos Aires (UBA) began to be developed in 2009.This program included the exchange of scholarship holders and professors that built a network of lessons that allowed adding the morphological look of the territory with the attention directed to the geographic,economic and socio-spatial dimensions from which it is addressed in Argentina the study of the territory.

The research resulting from this program analysed the changes produced by the patrimonialization and turistification of the Quebrada de Humahuaca after being incorporated into the UNESCO list of World Heritage in 2003 in the category of cultural landscapes②.This event,made visible a clear divergence between the local scale in a territory that until now had only local dynamics,and the global scale.In this context of extreme social vulnerability,it was understood that any intervention could be an opportunity but also a threat.

Thus,a few years after the declaration,the effects begun to become evident:the benefits of tourism did not revert to the local population,tourism was located only in the most accessible places and the archaeological sites shows signs of degradation.On the other hand,agricultural activity was in deep crisis,and mining activity generated serious impacts and rejection of the population.The construction of housing neighbourhoods did not respect any previous organization and houses were built in generic arrangements of any periphery.On the other hand,administrations showed a certain technical weakness and there was little or no communication between local governments and the community.

For all these reasons,it was more than necessary the existence of a project,to direct all the forces,agreed by the population and the agents that operate on this landscape.This was extremely important considering the weak institutional context.Thus,a series of researches were conducted,and they are still running today.The first proposal is to build a set of connected narrations that embrace various aspects and parts of the whole[16].In order to do this,different episodes were identified:the geological formation of the stream thanks to the Rio Grande and the conformation of a linear structure;the establishment of the pucarás,the first stable settlements,near the river but safe from the avenues;the construction of the Camino Real(Royal Road) on the layout of the old Inca Trail and the staging post system that forms a circuit of cultural exchanges;the agricultural activity that promotes the growth of populated centres,valuing their interaction with the natural environment;the use of the force of water for the operation of mills,linked to the existence of cooperatives;the establishment of the railroad,with its peak cycle and its decline;the festivities,which in this case are closely related to natural cycles;and many others could be listed.The elaboration of the information to develop these approaches started from the understanding of the different scales in which man relates to territory,which in turn have their correlation in cartographic representation scales.

Particular works were developed on the relationship between the local and the global from the geographical perspective,the study of the construction of new residential settlements from the urban perspective,the history of the representations of the place and the construction of an imaginary,the heritage architecture was also analysed,the economic dynamics that affect the most recognized towns by tourism and the socio-economic data of the region are also taken into account[17](Fig.3).

Although the presented research constitutes a singular academic work of vast dimensions and certainly interdisciplinary,its guidelines have served to nourish and enrich the work of the administration of the site,but also to incorporate them into the Territorial Strategic Plan and eventually contribute to the revision of the Plan of Management of the site,with a view to the concretion of some of its points.

Beyond the results,it is important to highlight the crucial importance of drawing in this kind of research.These kind of territories lack of a good cartography and only in recent years GIS data is available.Therefore,each field of research requires an intensive work on building intentioned cartographies[18].

Several recent doctoral theses,based on graphic work at various scales,have the capacity to build new knowledge.At the level of the cities,it shows how the “historic centers” are transformed,in the passage of residence to tourist equipment and the change of landscape that results from the new tourism facilities[19].In relation to the broader territory,new settlements are identified,which are built and occupied by those who were displaced by the operations in the “centres”[19-20].And,more broadly,these researches analyse the criteria for the delimitation of assets and the conflicts of selection and assessment that result from the designation of UNESCO in 2003.The series of maps produced show some of the logics that are at stake between infrastructure works,topography and patrimonial resources of the area.

Undoubtedly,it should continue to deepen measures of economic support or training,in order to promote alternatives that create employment and thereby maintain a landscape that includes much more than simple natural or urban settlements.Issues such as access to ownership of community lands;the availability of water for irrigation;the strengthening of marketing,financial and technical assistance to small producers;the integration of productive chains or the creation of an integrated system of productive information,are fundamental for a good management of this territory.

4.2 The Gaucho Trail

The pampas is an extensive plain of about 500,000km2that originally lacked of trees (Fig.4).The Spanish conquistadors brought cattle to this territory,which reproduced abundantly and today is the characteristic production of the region,along with cereals such as wheat and soybeans.This overwhelming landscape of singular beauty is,however,for the local inhabitant,a daily landscape and is difficult to apprehend due to its extension and because of the great distance between towns and cities.

The idea of the Gaucho③Trail (Camino del Gaucho) is based on the need to give value to the pampa landscape,preserve the coastal ecosystem and provide activity to the people of Buenos Aires beyond the traditional beach tourism activity.The project began in 1994,promoted by CEPA Foundation,with the idea of recovering the gaucho culture and using it as a mean to create cultural tourism,sustainable and inclusive (Fig.5).This system would combine the elements of the indigenous culture (the few that survive in this area),the gaucho culture,the European immigration,the agro-export economy,the native natural ecosystem and also the current beach tourism culture[21].

There are a large number of nature reserves in the pampas area.Some are Biosphere reserves recognized by UNESCO—such as the Coastal Park of the South or the Atlantic Park Mar Chiquita and its lagoon—and others are provincial or national reserves—such as the Bay of Samborombón,the Rías de Ajó,the Laguna Salada Grande and Punta Médanos.

One of the great challenges that this territory poses is its enormous dimension.We could frame the project area in a rectangle of 400×200 km,which offers multiple difficulties when thinking about the accessibility to different places and the connection between them,something that is undoubtedly easier to solve in more limited areas.In this way,the system is structured by a fast track(Highway number 2),which connects Buenos Aires with Mar del Plata in approximately 4 hours and a half,and by a slower route (provincial route 11)that goes along the coast,following the old Royal Road.These roads are in turn connected to each other by the local roads.

After analysing the different tangible and intangible values of the territory,it was decided to structure the proposal based on a network of eco-museums,or cultural tourism sites,managed by their own inhabitants –such as merchants,producers,educators,among others–,acting as small or medium enterprises.In this way,the program seeks to generate processes of social organization and encourage the participation of the largest number of actors:rural producers,merchants,tourism agents,local associations and scientific organizations,given that there is a great scientific research in the area,as well as local governments and international cooperation.

The network of eco-museums,which was finally established in 2001,is based on three categories of receptor sites.Antennas are the sites with the greatest capacity and exchange of information,such as large cities;the nodes are all natural and cultural resources selected as heritage to be valued;Lastly,the doors are the entry and exit points to the great itineraries of the Gaucho Trail,which also include general services.In turn,given the dimensions of the scope,four thematic itineraries are structured and can be carried out independently or connected to each other.

In the Río de La Plata Circuit it is possible to find the landscapes and customs of the River Plate culture,in a territory that began to form from the end of the Hispanic colonial period (18th century)with the first cart roads south of Buenos Aires and the first ranches,villages and forts.

The Circuit of the Lagoons and Beaches shows the immensity of the plain and its interwoven with the lagoons and channels of the Rio Salado basin,and its laborious drainage in the Atlantic Ocean,with coastal lagoons,huge systems of dunes,and large beaches of fine sand.Around here the Provincial Railway (now inactive) installed dozens of small stations and rural towns that today are part of a rich heritage.

The circuit of the Historical Towns are the most remarkable eco-museums of the Network,for their quality of both rooms and cultural museums,which reflect the ancestral and the telluric,in the advanced line of what was called “the conquest of the desert” and the fights between federal and unitary,from the period between the beginning of the Argentine institutional organization in 1810,and the de finitive institutional organization in 1852.

The Circuit of the Sea and the Sierras is developed between mountains and meadows,highlighting agricultural practices and the natural beauties of one of the richest areas of Argentina.The cities of Mar del Plata and Balcarce,are important urban settlements that intermingle with the rural environment in this area where tourism already has a century-old tradition.

Regarding management,it is important to highlight the role of the eco-museums in the dissemination of the project,which are constantly monitored to maintain the quality of the network.Likewise,the communication strategy and the importance of the periodical workshops to maintain traditional activities must be highlighted.The financing of the project,however,is based on tourism,given that there is still no external financing.

The path of the gaucho was institutionally recognized in 2006 as a priority corridor of the Province of Buenos Aires in the Strategic Federal Plan for Sustainable Tourism (PFETS,2006—2016).Since the beginning of the project and particularly in the last years,tourism activity has increased in the area.However,in recent years the network of eco-museums does not function as such,although each works individually.Surely the revision of the PFETS,still pending,can support the reconstruction of this important joint work and provide the necessary financing.

5 Conclusions

The interventions related to landscapes and their conservation proves to be a very fertile environment in Latin America and especially in Argentina.We would like to highlight,above all,the projective aspect of research and its important interdisciplinary component.From the specific field of architecture and urbanism,the idea of intentional reading is proposed as a powerful instrument to find project tools,because although it is true that other variables intervene in the territory—social,economic,political,etc.—it is advisable to know the material translation of these phenomena.

Regarding the results,we believe that there are several challenges still to be faced.On one hand,there is a constant financing problem for this type of projects,even though the two cases studied were incorporated to national plans of tourism developing.However,other perspectives beyond the mere touristic one should be considered,such as the productive or the environmental.Also,as we have mentioned,the issue of distances and connections between the different points of the considered territory implies accessibility problems that are central to the success of this initiatives.

The projects presented have one unifying element:the understanding of certain spatial patterns could be the possible guide of a project for that landscape.The effort of intentioned reading is the key instrument that we synthesize in this article.It is a useful method for building more diverse environments where its identity could be highlighted and,at the same time,it could be capable of giving alternatives for local development.The key element for the success of these kinds of initiatives is the local population because its compromise demonstrates an interest for the landscape and demands actions to be taken in order to preserve their heritage.This is linked to another benefit of intervening on these landscapes:their educational function,or the ability to tell a story that can be interpreted by the reader helps to maintain that heritage over time.

The importance of telling a story is not limited to the purposes of analysis and interpretation,but it is also useful for those who intervene in the territory.To build this story,it is necessary to elaborate a careful description.This means not only a representation of what exists or existed,but also serves to build and transmit ideas or interpretations,since no representation is totally objective.As Manuel de Solà-Morales said “Drawing is selecting,selecting is interpreting,interpreting is proposing”[8]and the creative component characterizes each of these three processes.

Notes:

① At its sixteenth session in December 1992 the World Heritage Committee adopted three main categories of cultural landscapes (UNESCO 1992:54-55) and included guidelines concerning their inclusion in the World Heritage List in the Operational Guidelines (UNESCO 1996:10-12,Paragraphs 35 to 42).Paragraphs 36 to 38 of the Operational Guidelines provide some definition of cultural landscapes.(See more:http://whc.unesco.org/archive/gloss96.htm).

② Link to the oficial document at UNESCO Site:https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/1116.pdf.

③ The gaucho is a man who herds and tends cattle,performing much of his work on horseback.

④ Fig.1©Díaz Terreno,2013;Fig.2©https://medium.com/@hotelhuacalera/conocé-quebrada-de-humahuacasu-historia-lugares-y-habitantes-2d365e71b6de;Fig.3©http://www.argentinaactiva.com;Fig.4©https://www.theargentinaspecialists.com/where-to-go/las-pampas;Fig.5©http://www.elembajadordelapampa.es/servicios/asadores-para-catering/attachment/asado-argentino-a-lacruz/.