拉美城市景观:一种强化的拼贴

著:(美)戴维·加弗努尔 译:邓可 向岚麟

1 引言:一个多元文化和多重影响下的地区

拉丁美洲是由多种因素形成的具有高度混杂的文化影响的地区:a)地域—地理、气候和生物多样性特征,因其横跨大西洋、加勒比海和太平洋,从北向南延伸,绵延6 000多英里(1英里约为1.61km),拥有世界上最大的山脉、热带雨林和沙漠;b)自15世纪初起成为欧洲帝国主义列强(主要为西班牙、葡萄牙,其次为法国)殖民统治的“新大陆”;c)20世纪美国以及更近时期的其他新兴经济体的强烈影响。

虽然这些外来文化的冲突往往以强加于本土文化为结果,但随着时间的推移,一种丰富的文化多元现象逐渐出现,并影响着生活中的各个方面,包括城市和建筑遗产。研究这种文化冲突或共存的过程可以帮助我们预见该地区仍然面临的挑战以及学术和专业的新趋势。

下文中,将结合拉美地区混合建成景观形成的主要历史时期,同时围绕其独特的景观、城市和建筑特点进行叙述[1](图1)。

2 前哥伦布时期:人与自然和谐共生的宇宙观

随着1492年克里斯托弗·哥伦布的登陆,开启了欧洲人对新大陆的征服和殖民,他们发现了拉美一些地区存在着高度发达的社会,一系列复杂的城市体系、区域联合、纯熟的城市布局和建筑[2]。

当时,阿兹特克文化和玛雅文化代表了这一地区文化与经济发展的主流,它们位于今天的墨西哥和中美地区,以及以秘鲁、玻利维亚和厄瓜多尔的安第斯山脉为中心的印加帝国的庞大的城镇群。这些城市的领土体系有着严格的社会和权力等级制度,由于强制劳动和奴隶制的作用,整体空间和主要建筑体现了统治者对民众的绝对控制。

早期西班牙的历史记载中描述了殖民者们第一次与这些文明相遇时所表现出的敬畏之情,不论是城市的组织、基础设施的建设、城市的整洁程度,还是那些石构的庙宇和公共空间,在他们看来无不令人叹为观止。除此之外,这些城市在形态上与当地自然环境完美融合,采用了生态都市主义,使得大规模的都市农业、复杂的灌溉系统乃至城市中心的卫生防护成为可能;这些在当时的欧洲城市中是没有的,与在其他地区所见的也不可同日而语①。

来到阿兹特克中心城市特诺奇提特兰城(今墨西哥城)的殖民者 Hernán Cortés,被这座建在湖心岛上的巨大城市深深地震撼了—海堤公路、纵横交错的水网、卫生系统以及以一种以豆荚(名为chinampa)为主的十分高产的水生都市农业[3]。

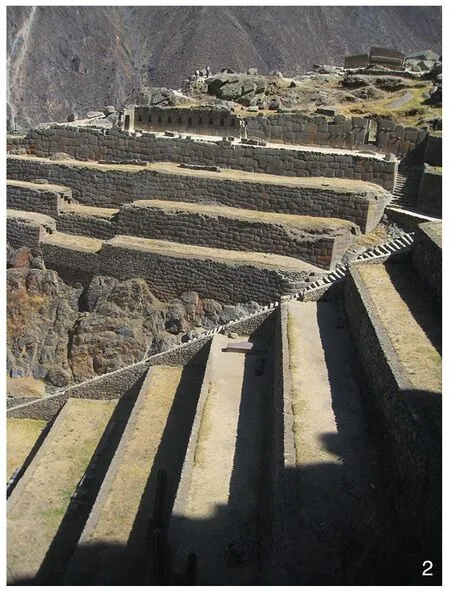

西班牙人和葡萄牙人在拉美殖民的主要目的是将他们攫取的自然资源(金、银、宝石、优良木材,后来还有农产品)运回欧洲,并将欧洲的宗教和文化进行输入。这些原因导致了前哥伦布时期殖民城市受到侵蚀和破坏,并被破碎的欧洲模式的景观所逐渐取代。因此,除了那些位于偏远地区、在欧洲殖民者到来之前被遗弃的,或是那些日前在密林中被发现的城市和建筑的遗迹之外,前哥伦布时期的建筑遗产所剩无几。这一时期最典型的建筑类型是仪式性的金字塔和纪念性的建筑群。在诸如特奥蒂瓦坎、奇琴伊察、帕伦克和蒂卡尔等地,都有着中美的石头装饰和浮雕;安第斯山脉的高地中如皮萨克、萨克塞瓦曼、欧雁台和马丘比丘等地,在房屋和庙宇中修建了精细的石墙,在城市和农田中还结合地形建造了石阶(图2)。大多数土著居民的房屋由轻质材料如木材、甘蔗、纤维以及土方等建造,随着时间的推移,这些材料与当地自然环境很好地融为一体。

这个时期的建筑和工艺品中的重要美学元素在如今的视觉艺术中有所体现,特别是在壁画、陶器、织物、平面设计中,有的则体现在当代建筑中(图3)。

2 秘鲁皮萨克,印加梯田Inca agricultural terraces in Pisac,Peru

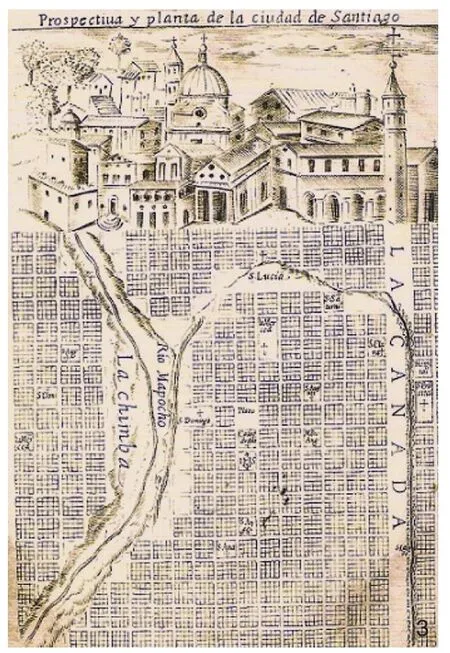

3 圣地亚哥早期殖民地图Early colonial map of Santiago de Chile

3 殖民城市:城市原型的植入

从欧洲殖民开始的殖民时期延续了3个多世纪,到了19世纪30年代,拉美大多数的殖民地发展成为独立的国家。殖民地城市是文艺复兴和巴洛克时期的产物,是为了实现对领土的迅速占领和政治控制的强大军事行动的结果。为了开展这项被认为是历史上最大规模的殖民运动,1573年,西班牙王国颁布了《新领地和平发展条例》,亦称《独立法》,对城市的管理和设计等作出了简要规定②。

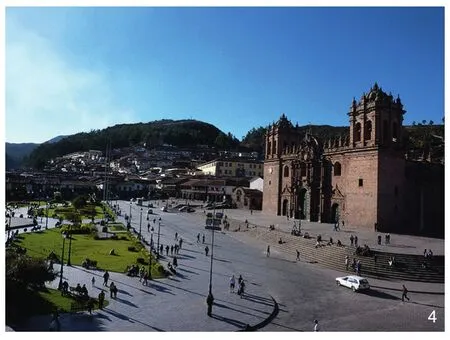

历史上被认为起主要促进作用的城市殖民手段是笛卡尔方格网在近800个西班牙殖民点中的广泛使用,通过这种形式对当地进行文化殖民(图4)。新城建设的第一步是清除植被,体现了人类意志凌驾于自然之上③。公共广场由于其枯燥乏味的风景,被改造成市场和宗教场所,同时提升了围合在其周边的公共建筑(教堂、市政厅、监狱或军事设施)的高度。正如丘埃卡(G.Chueca)和托里斯(B.Torres)所言:“城市与乡村的区别不仅是其活动类型和人口组成的不同,最重要在于城市的几何设计。城市是文明的标志。殖民者们通过新城建设来向当地人民展现他们至高无上的文化地位。[4]”

《独立法》中明确地提出了选址、与水源的距离、是否有土著居住(这意味着那里是否适合居住)、中心广场的位置和比例,以及引导城镇扩张的次中心的选址等要求,同时限定了这些广场周边重要的市民和宗教建筑的位置和建造方式④。此外,法律中还建议在炎热地区降低街道宽度,以便至少在街道的一侧形成建筑阴影,如波多黎各的圣胡安、哥伦比亚的卡塔赫纳⑤和巴拿马的巴拿马城[5](图5)。

条例中规定,每个街区被划分成4个地块并分配给这座城市的殖民者们。只有在非常富裕的城市里,这种街区划分的方式才能很好地施行。地块很快地被划分并传给殖民者的后代。越富裕的群体的地块和房屋越大,且越靠近主广场,反之亦然。

尽管条例中明确了重要公共和宗教建筑的基本模式,但住宅和商业建筑却是按照西班牙和葡萄牙自身的传统而建造的,又同时受到伊斯兰的影响[6-7]。为了将公共空间和私人空间明确区分开,规定住宅和公共建筑要形成连续的街道立面。越靠近地块前端的房屋越正规化,越靠近后端的房屋则越家庭化和生活化。建筑物的高度、立面栏窗的数量、多层建筑中阳台的设置、主入口和面向街道一侧的门窗装饰等都体现了户主的社会地位。

非住宅建筑上的装饰物的大小和复杂程度取决于城市所在地区的富裕程度;建筑材料的选择取决于它们在当地的可获得性,主要是土坯、夯土厚墙、带有泥垫的藤条、石头或沿海地区的珊瑚礁。在原住民大量聚居的地区,建筑和艺术品中出现了许多本土的图案。这时的拉丁美洲,文化混杂现象就已经在城市和建筑中产生了[7]。

大多数拉美国家都不乏杰出的城市和建筑实例,特别是在被殖民之前就已经有着更先进的土著群体和人口更稠密的地区,如:墨西哥、危地马拉、哥伦比亚、厄瓜多尔、秘鲁和玻利维亚;或者那些作为保卫其港口的重要城市,以及准备运往伊比利亚半岛的货物的储藏地,如今天的巴拿马城、卡塔赫纳、拉哈巴纳或波多黎各圣胡安。

葡萄牙人在伊比利亚半岛占领了一块大殖民地—巴西。与西班牙人一样,出于相似的经济和宗教原因,他们制定了一个类似于新城建设的蓝图。然而,葡萄牙并没有颁布一部像西班牙那样的城市设计导则。因此,除了部分方格网城市的建设,更多的城市采用了传统葡萄牙城镇的有机增长模式。得益于其土地的富庶,且因葡萄牙议会于1807年决定将首都和平地移交给巴西,从而使其免受独立战争的摧残和破坏,因此众多杰出的巴洛克式殖民建筑得以保留⑥。

如今,部分被西班牙和葡萄牙所殖民过的城市中的方格网整体或城市局部已经被联合国教科文组织列入世界遗产地⑦。此外,对大陆殖民地的主要港口和加勒比海岛起着防御作用的设施也同样重要。

随着时间的推移,殖民时期的城市所特有的城市形态和建筑遗产已经受到了拉美国家的高度重视,他们对其进行保护,将其视为独特和多元文化的象征。此外,殖民城市依然存在着社会分层,同时也成为经济活动的中心和旅游目的地(图6)。

4 秘鲁库斯科,阿马斯广场Plaza de Armas,Cuzco,Peru

5 哥伦比亚卡塔赫纳德印第亚斯,殖民街Colonial Street in Cartagena de Indias,Colombia

6 巴西里约热内卢中心Avenida(19世纪下半叶)Avenida Central in Rio de Janeiro,Brazil (second half of the nineteenth century)

4 共和时期:城市绿化

到了19世纪30年代,拉美大多数前殖民地国家获得了独立。西班牙能够统治的仅剩下在古巴和波多黎各的加勒比地区严密防控的海岛⑧。经过近20年的血腥暴力的独立战争,拉美国家最终进入到法律、经济、文化和城市发展变化的新时期。

与其他欧洲国家特别是英国、法国以及日耳曼国家的贸易往来,深刻地影响着这些新独立的共和国,并改变着它们的生产、制造和出口方式以及城市景观。法国在文化上被许多拉美国家所效仿,对这些国家的法律、政治、教育等制度都产生着影响,并成为城市、景观和建筑设计方面的示范。这种新的经济和政治关系影响着这些地区的农业生产和出口方式(如甘蔗、咖啡和可可)。这是经济依赖和文化同化下的新时代的曙光⑨。

对外贸易的新机遇促进了拉美地区的城市发展,推动了基础设施的建设,如港口、铁路、公路、渡槽、工业区以及医院、市场、学校和大学等服务设施和军事设施。这也引发了20世纪初的第一批社区住宅的诞生。因此,原本紧凑的殖民地城市开始采用欧洲的城市建设模式和建筑风格并不断扩大[8]。这使拉美的城市景观发生了许多重要的变化,并对其社会关系产生了一定的影响,主要是:

1)农村土地迅速转化为城市土地,激发了投机性房地产市场,也造福了一群企业家(即那些殖民时期的土地所有者)。这个新兴的富人阶层开始迁移到不断扩大的城市的周边居住—在绿色景观的庇护下—以逃避传统城市中心区所带来的拥挤、污染和社会问题⑩。

2)人们普遍热衷于景观和城市绿化,并将其作为城市美化的手段,建设了林荫大道,使其不仅成为社交和休闲的场所,同时还吸引了房地产投资者。与殖民地城市忽视当地的景观和文化不同,共和时期早期的城市在注重地域、环境和植物的和谐方面有了很大提升(图7)。

共和时期自然要比殖民时期更具探索性和开放性,以便将欧洲的城市和建筑类型朝着适应当地条件改善。这期间,政府通过不同渠道的借鉴、充分汲取公众的意见,对拉美良好的自然本底和丰富的植物资源有了深入的认识。这个时期可以被认为是拉美版的田园城市和城市美化运动。

许多城市试图仿效奥斯曼式的巴黎大道和纪念碑,有时甚至将它们用在既有的城市肌理上;除此之外,这些城市建设手法还被用在以农业为主的自然环境中[9]。许多国家建设了新城,以适应新的经济活动,开采或加工咖啡、香蕉、橡胶、矿产、木材或纤维等自然资源。欧洲的建筑师、工程师和市民被邀请参与到这些项目中来,并使用巴黎美术学院最流行的设计元素。

7 智利圣地亚哥的森林公园,连接起旧的殖民地方格网与19世纪的城市新区Parque Forestal in Santiago,Chile,linking the colonial city to the nineteenth century expansion

8 阿根廷拉普拉塔新城鸟瞰图Aerial view of the new town of Ciudad de La Plata,Argentina

拉丁美洲所有重要的城市都不乏欧洲城市模式和建筑类型的影子⑪(图8)。

智利港口城市瓦尔帕莱索因其杰出的折衷主义建筑群而被整体列入世界文化遗产。这座城市是南美洲重要的港口和商业中心之一。这座城市与陡峭地形的结合,使用倾斜的电梯,以及它的折衷式建筑,使之成为拉美后殖民混杂的独特范例(图9)。

5 拉美现代主义:适应本土文化的城市化

20世纪中叶之后,拉美国家经历了快速的城市化、现代化和工业化,而此时,其富裕的北方邻国—美国已成为全球的经济和军事霸主。

在此之前,大多数拉美国家还是农业国。在不到50年的时间里,这个地区的城市人口比例已经等同甚至超过了农村人口。如今,与其他主要为发展中国家的地区的城市化率相比,拉美的城市人口比例是最高的⑫。在当时经济非常发达的国家,如墨西哥、古巴、委内瑞拉、巴西和阿根廷,移民中有相当一部分是来自其他拉美国家的,特别是那些在二战期间饱受战争侵袭的国家(图10)。

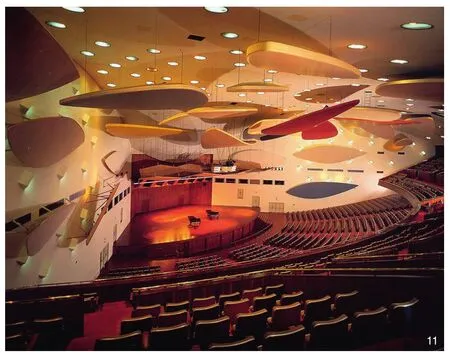

在这个地区走向经济繁荣的同时,也开始广为采用城市规划和建筑中的现代主义思想,来自二战中被摧毁的欧洲国家的重建,以及美国和加拿大的郊区化经验。北美正在经历的变化对美洲的其他地区产生了强烈的影响,这些地区通过学术交流以及通过修改规划和建筑法规来仿效北美⑬。拉美当时正在经历的社会、经济和城市结构转型,与中国过去20年所经历的变化十分相似(图11)。

在现代主义(起源于国际现代建筑大会,CIAM)的影响下,该地区诞生了一批现代城市和建筑设计的杰出作品,旨在得到世界范围内的运用。然而,它们毕竟是适应拉美当地条件并带有地域色彩的作品[10],其特点是对本土环境和气候的适应、纪念性强、强大的城市结构、注重公共空间的设计以及城市设计、建筑设计、景观设计、艺术设计和其他设计的试验性结合,并且在某些情况下,重新诠释了本土、殖民和后殖民建筑的特征。

2015年纽约现代艺术博物馆举办的名为“拉美建筑”的展览,展示了拉美城市20世纪50年代和60年代在现代建筑和城市设计上的杰出成就。一些大规模的、大胆的公共投资项目成了其中的亮点,包括社会住房、公园、大学、公立学校、行政中心、酒店、医院、游乐场等。

9 巴西贝洛奥里藏特,毗邻帕姆普哈湖的舞榭(奥斯卡·尼迈耶设计)Dance pavilion,Lake Pampulha,Belo Horizonte,Brazil,by Oscar Neimeyer

10 20世纪60年代的巴西首都巴西利亚,纪念性轴线Monumental axis in Brasilia,new Brazilian Capital since the 1960’s

这些项目象征着公众的意愿,以及在全球范围内发挥突出经济作用的强烈的国家自豪感和认同感。这里吸引了为逃离饱受战争蹂躏的欧洲甚至日本的高水平的专业人员、教育工作者和工匠。在这个开放的移民过程中,拉美的文化混杂被进一步加强,设计方案在质量和多样性方面都得到了提升。

一些20世纪中叶最杰出的设计师,如瓦尔特·格罗皮乌斯(Walter Gropius)、乔斯·路易斯·塞特(Jose Luis Sert)、路德维希·密斯·凡德罗(Mies van der Rohe)、理查德·诺伊特拉(Richard Neutra)、罗伯特·布雷·马克斯(Roberto Burle Marx),以及许多在学术和专业实践领域对古巴有过重要影响的人曾到访拉美。这些影响产生了与马里奥·罗曼纳赫的设计同样杰出的地方现代主义作品,它们很好地结合了场地和当地气候条件,并运用了本土工艺和材料⑭(图12)。

许多设计明显表现出受勒·柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)的影响。有人认为,柯布西耶所提倡的狂野、开放、通透和格网结构的建筑更适合热带地区,那里可以利用自然风的先天条件,而且建筑的形体可以通过对比强烈的光影得以凸显,而不适合亚热带地区[11]。现代主义运动在拉美受到了广泛的青睐,如在巴西,现代主义的遗存对当下的设计仍产生着持续的影响⑮(图13)。

这其中最著名的有:位于巴西新首都巴西利亚的行政、住宅和商务中心区,位于墨西哥城的墨西哥国立自治大学(UNAM)和位于加拉加斯的委内瑞拉中央大学(UCV)—它们现在都已成为世界遗产。圭亚那城是区域和新城规划中的一个典型,由哈佛大学和麻省理工学院城市研究联合中心以及委内瑞拉圭亚那公司于20世纪60年代设计。其建设旨在让这片无人区实现以钢铁和铝生产为基础的工业化。设计中采取的措施包括:保护流域和栖息地,从而保证水力发电,以及在20世纪80年代设计的、与大坝和公路等大型基础设施一起建造大型公园系统。

这一时期的另一重要贡献是景观设计师所发挥的作用,这些迷人的公共空间在社会分层和空间隔离日益加剧的今天显得不可或缺,它们为所有社会群体提供了一个彼此交流的共同场所。这里我们必须提到20世纪最重要、最高产的景观设计师之一:罗伯特·布雷·马克斯。虽然他出生在巴西,但他的设计对整个拉丁美洲乃至全世界都产生了重大影响。他的设计为专业领域开辟了新的方向,并引发了对本土景观和植物的广泛重视,打破了此前崇尚欧洲形态、美学和表现技法的景观传统。

马克斯的贡献在于,他在拉美和其他大陆进行植物学探索的过程中,发现了数百种新的植物品种(图14)。他所设计的大型休闲公园,如位于巴西圣保罗的伊比拉普埃艾公园,位于委内瑞拉的加拉加斯埃斯特公园、马拉开波植物园,都体现了他对植物结构、形态和表现方面的深刻理解,通过巧妙的设计使之成为人们前来休闲、互动和学习的场所⑯。

马克斯在巴西里约热内卢海滨设计的两处景观都得到了世界级的赞誉,一处是科帕卡巴纳海滩沿岸用石板重新铺就的人行道,另一处是弗拉明戈公园,它们给这座独具魅力的城市增添了亮丽的城市和自然景观,享誉世界。他在全球留下了将近2 000个设计作品,这些作品又影响了拉美其他著名的景观设计师,如墨西哥的马里奥·谢特兰(Mario Schjetnan)[12],或与他一同在委内瑞拉工作的出生于智利的费尔南多·塔博拉(Fernando Tábora)。

这些项目中许多是由国家政府—多数是高度集权的政府—以及军政府投资的,以展示这些政权“对国家福利的能力和贡献”。这一时期,现代主义设计的狂热对私人投资的项目产生了溢出效应:规模较小,但非常丰富,而且同样具有探索性⑰。这无疑是拉美地区探索建筑、城市化、工业、平面设计及前沿美术的黄金时代。

但是,拉美的现代主义城市规划作品远不如其建筑和景观作品受到认可,这是由于其广泛地采用了标准化的设计规范,因此造成了如下结果。

1)现代规划范式中将城市当作崭新的功能体,通过房地产开发来推动建设,并通过不同等级的道路将不同的单一类型的功能区连接起来,同时鼓励建造孤立的塔式建筑,这在很大程度上改变了城市的形态和性能,将老城不断铲平而新城毫无特色。

2)现代城市准则的应用还导致城市扩张、耕地流失、生态系统受损、社会和空间隔离以及高品质公共空间的缺乏,并造成了极大的机动化交通依赖和能源消耗。

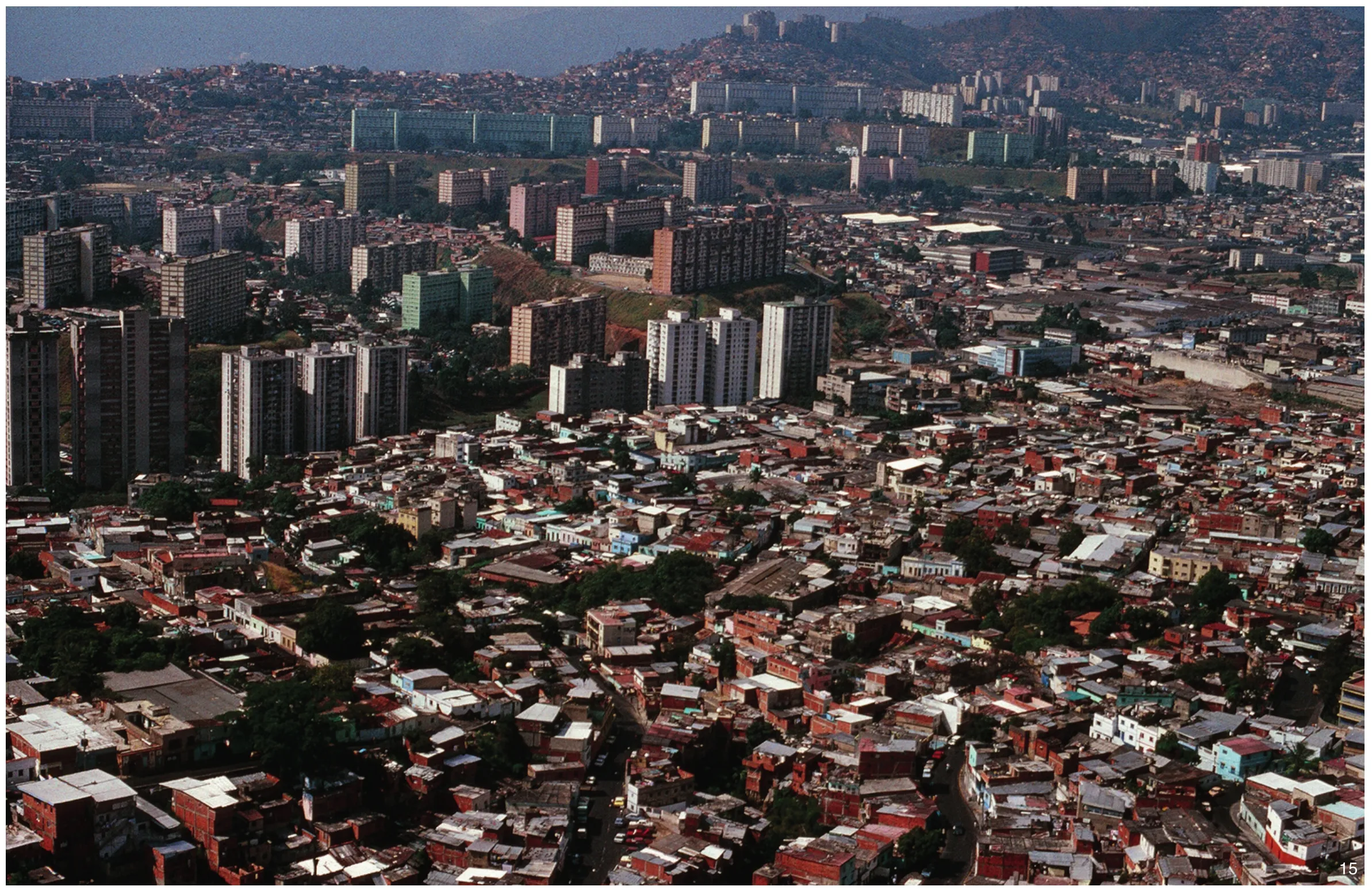

3)由于现代城市准则中没有一套机制来保障那些无力购置房产的低收入移民,因此非正规城市开始出现,它们别无选择地散布在城市的郊区(通常在易受灾地区),这无疑导致城市中严重的不平等以及社会和空间的碎片化⑱(图15)。

6 城市设计实践:对特定地域的适应

在20世纪最后几十年中,拉美不乏有趣的城市设计和场地改造,并强调了公共空间、城市复兴、场所的独特性以及对历史环境和建筑的重视和再利用,与普通的、缺乏场所感的、隔离的现代城市规划形成鲜明对比(图16)。

11 加拉加斯,委内瑞拉中央大学,带“云”的玛格纳礼堂(亚历山大·考尔德设计)Aula Magna ,UCV Campus,Caracas,Venezuela,with “clouds” by Alexander Calder

12 古巴拉哈巴纳,与风景“对话”的住宅(马里奥·罗曼纳赫设计)Residence “connected” to the landscape in La Habana,Cuba,by Mario Romanach

这一时期的标志性设计项目中包括了对工业区的改造。以阿根廷布宜诺斯艾利斯的马德罗港项目为例⑲,该项目重新利用了港口的仓库和码头,以及梅尔卡多·德·阿巴斯托(20世纪30年代建造的中心市场)已经废弃的混凝土拱形建筑,将它们打造为商业和娱乐设施;另一个例子是巴西圣保罗由生产仓库改造的名为SESC Pompèia的大型文化和表演艺术中心。

其他旨在建立大型开放空间和混合用途场所的项目还包括,委内瑞拉加拉加斯市内一条长达一英里(约1.61km)的高速公路被改建成一条城市大道(Bolívar大道),以及得益于第一条地铁的修建,一条同样长度的拥挤不堪的街道被改建为一条商业步行街(萨巴纳格兰德大道)。此外,值得一提的是,厄瓜多尔瓜亚基尔在瓜亚斯河河口开辟了一条重要的海滨长廊,以此带动了经济活力,并成为社会互动活跃的场所。

得益于建筑和城市规划师贾米·勒讷(Jaime Lerner,库里蒂巴市长)以及建筑师恺撒·玛亚(Cesar Maia,里约热内卢市长)20世纪末的杰出执政,巴西还奠定了许多重要的里程碑;在哥伦比亚,数学家兼教授塞尔吉奥·法贾尔多(Sergio Fajardo,麦德林市长)以及经济学家恩里克·佩纳洛萨(Enrique Peñalosa,波哥大市长)的第一届执政期间都对城市做出了同样的贡献(图17)。

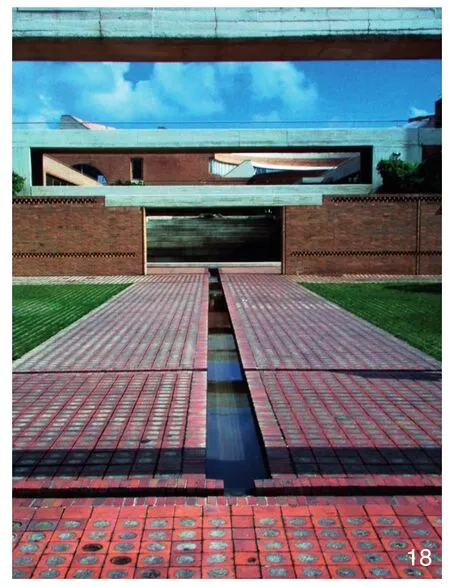

举个例子,佩纳洛萨在任职仅3年的时间里,就率领高质量的管理及专业团队成功地化解了非常棘手的城市问题,将城市环境放在首位,并以此证明了良好的公共服务可以改变一个地区治理中的习惯性低效、低质和腐败。的确,他的管理是自上而下的,但不是谁都能成功地让一座拥有近900万居民的首都一跃成为领先的区域中心(图18)。

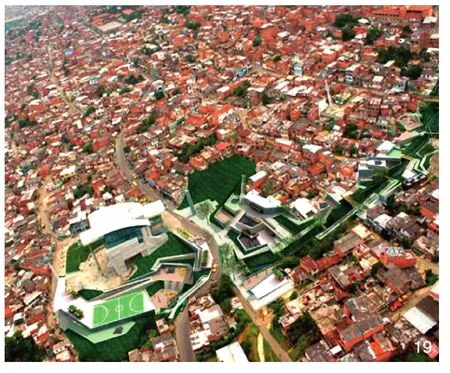

具体地看,佩纳洛萨在波哥大取得了如下成就:建立了健全的、也是该市第一个综合性快速公交系统,修建了总长度达250km的林荫道和自行车道,为20万名学生新建或更新了几十处教育设施。此外,他还新建了主要服务于贫民窟的数十个公园和一个大型公园图书馆系统,以及以增强公共空间和公共设施为重点的大规模住房补贴项目等。这些举措对减少社会差异、实现大都市区域的均衡发展起到了积极的推动作用。波哥大市因此多次获得国际荣誉,佩纳洛萨的遗产为后续执政者提供了不断努力和创造性改进的可能⑳(图19)。

13 加拉加斯,委内瑞拉中央大学(卡洛斯·劳尔·维拉努瓦设计)UCV Campus,Caracas,Venezuela,by Carlos Raúl Villanueva

14 委内瑞拉加拉加斯,东方公园(罗伯特·布雷·马克斯设计)Parque del Este,in Caracas,Venezuela,by Roberto Burle Marx

7 非正规城市:从排斥到全面接纳

拉美地区的城市化和现代化伴随着农村人口的流动,但这种流动并没有引起正式的城市规划和房地产开发的关注。这就造成旧殖民时期城市中心的富裕阶层不断迁往新城区的同时,大量低收入者不断涌入的现象。同时,随着城市边缘、旧城区、沟壑或陡坡等不利于城市开发地带的非正规住区的逐渐形成,城市在这个过程中不断发展、扩大和固化。起初,不管是政府、学者还是专家都不接受这种非正规性,并认为可以通过社会住房保障项目加以制止和消除。他们没有意识到,正式的城市规划解决不了这些不断涌入的极低收入的移民对住房的需求,或者简单地说,这些移民根本买不起商品住房,因为他们既没有正式的工作,也没有多少积蓄。几十年来,当局和公众已经清楚地看到,非正规的定居点还将继续存在,并且在许多情况下,它们已经成为城市化的主要构成形式。

在这些走上民主道路的国家,尽管这些地区还存在很大的问题,但这里的居民同样享有投票权等政治权利。因此,政府部门开始对这些居民点采取简单的干预措施,如提供水、电,设立小型学校、医院和体育设施,以及设置人行道和楼梯,有的地方还统一对房屋立面进行粉刷以使其更美观。这些行动在选举之前尤为明显[13]。

大多数拉美国家修改了原先的法律制度,明确了非正规城市在城市组成部分中的合法地位,并使他们的诉求得到政府部门的考虑,同时探索其技术标准和管理机制。

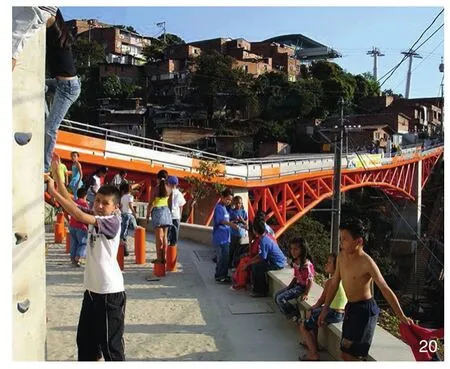

在20世纪的最后10年中,政府为改善这些居民点的生活条件采取了许多重要的举措。这些举措好比城市手术,因为需要对原本紧凑的城市空间进行细致的操作,从而创建公共空间,改善可达性,引入基础设施和公共服务,以及对危险地带的居民进行搬迁。为了使这些项目顺利实施,同时尽量减少对原有社会关系的破坏,原住民的安置点尽量选在住区内部或附近。这类项目在委内瑞拉的加拉加斯、巴西的里约热内卢以及哥伦比亚的波哥大和麦德林得到了比较整体的实施(图20)。

在麦德林市长塞尔吉奥·法贾尔多的执政下实施的多个项目,以及建筑师亚历杭德罗·埃切弗里(Alejandro Echeverri)的技术水平和实力,都已得到世界的认可,他们创造了高质量的城市景观和建筑,使城市产生了可喜的变化和社会效益。在这类社会的城市化中,麦德林已经成为世界的示范㉑。这座城市中最贫困、最具暴力因素和破碎最严重的非正规住区是项目优先关注并实施的对象,主要包括使用缆车或室外自动扶梯提供机动交通,建立公园、图书馆、新学校和文化设施等。此外,不同项目按分阶段组织的方式、公众参与和自治的方式、提供文化活动的形式以及维护管理等同样重要。2014年,世界城市论坛在这座曾经备受挑战的城市召开(图21)。

非正规住区的改善项目所产生的积极的社会环境影响,最终影响了学术、实践和行政等各领域,回应了作为复杂拉美文化和拼贴城市中重要组成部分的底层群体的诉求,同时也成为其他大陆的借鉴。

然而,拉丁美洲仍然是殖民时期以来社会经济不平等程度最高的地区[14-15]。随着非正规住区不断在正规城市的外围生长,这种不平等性也不断扩大,加剧着城市问题。如果不解决非正规住区的扩张问题,势必会增加环境和社会压力以及治理难度,并直接影响到这些国家的国际市场竞争力。

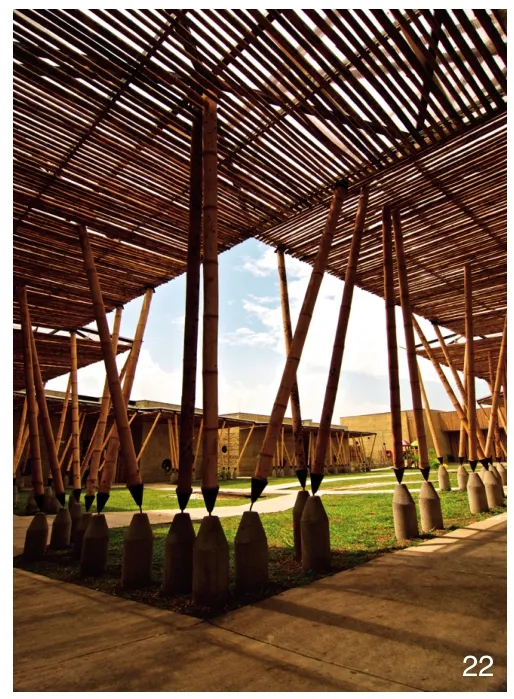

但如果真的这样做了,似乎也不合理,这必将导致非正规住区的进一步扩张。在笔者的研究和教学中,重点关注对非正规住区的扩张趋势的预测和管理,以及根据不同的环境,制定标准、简单和灵活的适应性设计方案。这在笔者的著作《未来非正规城市的规划与设计:重塑自建城市》第3~7章中得到了具体的阐释,亦可见西班牙语的增补版《新的非正规城市的设计》㉒(图22)。

15 委内瑞拉加拉加斯,“1月23日”公共住房项目,建于20世纪50年代The 23 de Enero public housing project in Caracas,Venezuela,built in the 1950’s

8 景观设计新动向:早期生态运动和社会化建筑趋势

在最近的“拉美国家建筑·景观·城市双年展”上,为一些此类项目颁发了奖项,体现了学界和专业人士对从根本上解决这类城市问题的态度和责任心的提升。此类项目多是设计竞赛的获奖作品,这种方式给青年设计师和小公司提供了参与到这类解决尖锐社会和环境问题的前沿项目中的机会。除了形态和美学方面,这些项目还涉及实施层面,如设计环节中的公众参与、建造和运营、借鉴自发建造技术的本土低成本和低维护材料的运用等。旨在发扬前西班牙时期的设计和材料的本土复兴也是目前的一个趋势,以应对当前不可持续的问题,当然,这往往会令建材经销商不满。学界在这类探索中发挥着主导作用,而哥伦比亚又一次引领了潮流22(图23)。

目前,拉美地区在公共空间、公园和绿廊设计等许多重点项目中都有所实践,并着眼于生态以及形态、水管理、行为学和植物学等方面的问题。这在智利和哥伦比亚的一些城市中有所体现㉓。

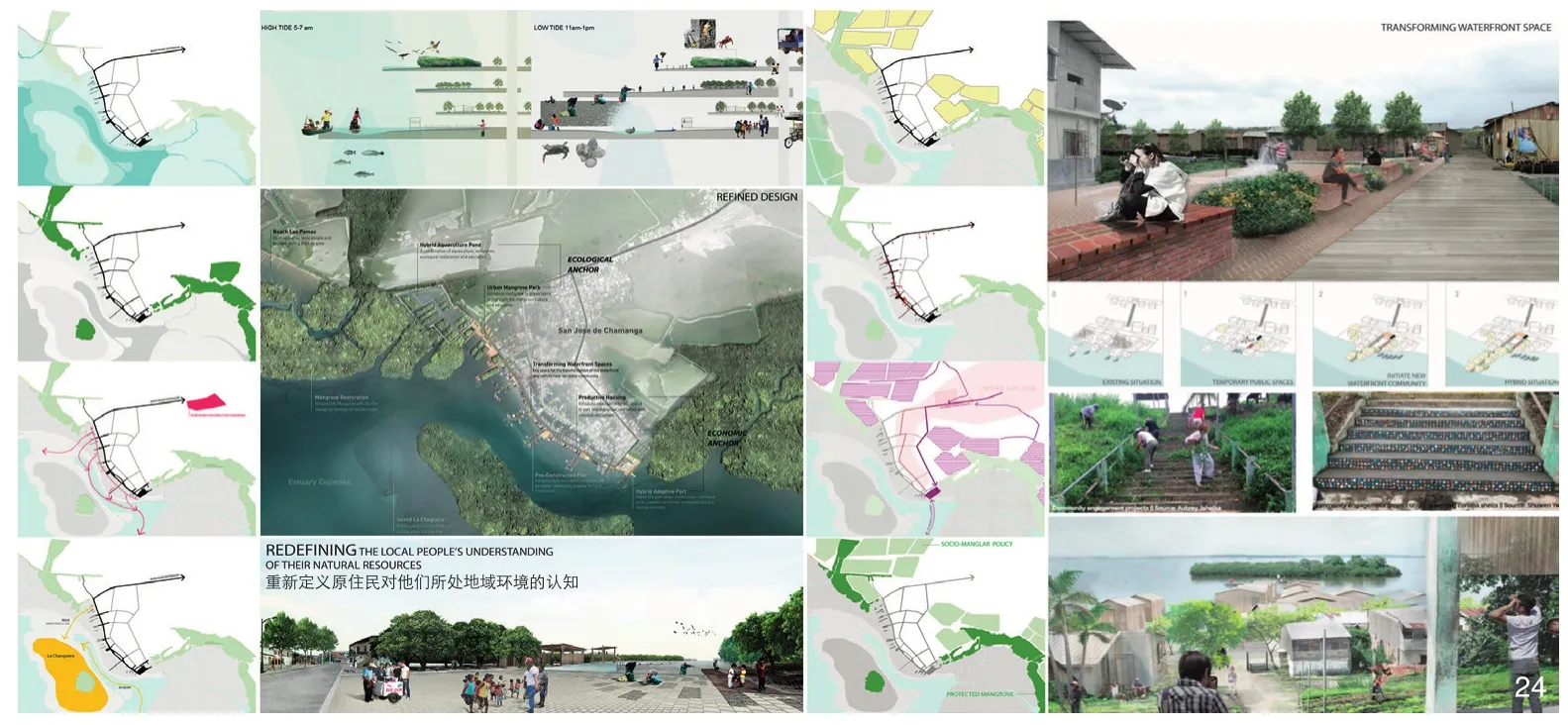

在防灾减灾方面也同样有所作为,如2000年委内瑞拉加勒比海岸的加拉加斯遭受洪水之后实施项目㉔(部分实施),2017年智利海啸和地震后的城镇修复(计划),2014年受森林火灾影响后的瓦尔帕莱索高海拔地区非正规居民点的重建(部分实施),以及针对2017年波多黎各遭受的连续两次飓风所造成的严重破坏的重建项目(正在实施)。这些举措促使政府、机构、学界和专业人士以更加全面、开放的方式进行思考。

此外,气候变化和环境规划的缺失已被证明会使得自然敏感地区受到越来越显著的挑战,而贫民区又往往是其中最脆弱的(图24)。

然而,在大多数拉美国家,由于高成本和复杂的管理技术,生态恢复、绿色基础设施、水管理、提高渗透性、改善或解决气候变化和都市农业、创收活动等方面的实践仍然较少,因此并没有过多关注那些受挑战的城市。但是,这里的学术机构以及一些对拉美感兴趣的北美和欧洲机构,在让学生了解这些问题方面发挥着关键作用,并且必将培养出一代年轻的专业人士和领导人,使他们参与到实践中去(图25)。即使拉丁美洲的区域多样性和生物多样性很强,城市的指数增长还是不断侵蚀着脆弱的生态系统和宝贵的农田。城市建设和生态保护之间的鸿沟仍然存在。

9 新的挑战

新世纪的到来,使世界经济政治格局进入到全球化时代,也给拉美的城市景观带来了剧烈影响。值得注意的是,新技术、大型公司和特许经营已普及全球;同时,基础设施、运输和住房等城市相关领域开始给拉美地区或中国、俄罗斯和伊朗等国带来投资和政治关系。

从城市形态—地域的视角来看,殖民时期的城市景观是通过重复国外紧凑而方便步行的城市准则和建筑类型而形成的。在共和时期、现代、后现代的城市设计和生态设计时期,以及在当前的城市规划标准和发展趋势下,城市形态逐渐走向了多样化。因为该地区已经变为城市主导的区域,城市呈指数式扩张。其结果是产生了拼贴式或复合式人工景观的共存和变化,并通常适应于本土条件,形成独特的拉美产物。

拉美的混杂性使得该地区成为接受不同影响的海绵,成为适应和实验的沃土。这一地区从20世纪中叶开始经历的快速经济增长,现代化、工业化和城市化进程是采用外国模式进行的。这些外国模式给这里的自然系统以及城市、建筑类型和文化景观带来过挑战。随着时间的推移,它们被改造和完善,从而变得更本土化。

然而,最近引介的全球化城市和建筑语言的结果并不理想,并导致了该地区从未有过的蔓延和社会隔离。圣地亚哥、波哥大、圣保罗和墨西哥城的购物中心、商业中心和办公大楼与亚洲的并无多大不同,而亚洲又与北美和欧洲相似。在蒙特利、巴兰基拉、马拉开波和拉巴斯,大规模开发的门禁小区成为这些不断扩大的城市的共同特征。虽然这些小区以安全的名义出售,但它们在公共领域增加了不安全感,同时促进了城市的蔓延和汽车依赖,隔绝了人们在公共空间中的社交活动,并给城市管理带来困难。

正如丹尼尔·费尔德曼(Daniel Feldman)所描述的,“拉美的城市和建筑艺术也受到跨国公司的影响,它们为该地区的政府提供标准化和规范性的城市设计导则,而忽视了本土特点。这些文件和预包装的解决方案经常被地方政府当作支持大规模城市管理的技术和财政依靠(许多时候具有高政治回报),导致了对外国技术和投资的依赖”(作者与哥伦比亚建筑师费尔德曼的对话)。

尽管该地区的国内生产总值有所上升,但新千年伊始就出现了强烈的政治两极分化(当然是社会经济差异的结果),并产生了左翼军事化运动和极端右翼运动这种不容乐观的政治动荡,民粹主义的出现加剧了社会分裂,并在国家内部和国家之间造成了文化和领土的割裂(可能类似于美国、欧洲、亚洲和非洲的情况)。

拉美地区未来复杂的社会经济和环境议程悬而未决,它要求拉美国家对外国影响以及城市、景观和建筑类型的本土化发展做出更具选择性和批判性的适应调整。该地区需要进一步加强国内研究,并以实践、学术和项目为依托,使之具备现代主义那样的创新性,或者就像最近应对非正规城市的方法那样,为公共和私营部门提供适合的路径。

拉丁美洲丰富、多元、实践性的城市、景观和建筑作品,以及其融汇外来文化、适应本土条件,同时善于创造富有特色和多元化设计的能力,或可以成为那些正面临挑战又不忘本国历史遗产的其他新兴经济体和快速城市化国家的借鉴。

致谢:

诚挚感谢奥斯卡·格劳尔(Oscar Grauer)、尼克·佩夫茨纳(Nick Pevzner)、伊莎·库马尔(Ishaan Kumar)和哈里克·托马西尼(Heryk Tomassini)给予本文的支持。

注释:

① 马里奥·谢特兰,杰出的墨西哥景观设计师,他对当代设计中传统材料的运用做了大量的研究。

② 这部名为《独立法》的皇家法律以文字和条款的形式成为广泛的新城规划中所遵循的城市设计导则,具有法律地位的同时,也塑造了新城的同质性。

③ 土地清理虽未被明确列入条例,但却是普遍采用的做法。

④ “广场应该是正方形或长方形,在这种情况下,它的宽度至少应为其长度的一半,因为这种形状最适合使用马匹的节日和任何其他应该举行的节日”,“广场的规模应该与将要建立的城镇的预期重要性成比例”。这些是条例中所提出的类型。

⑤ 卡塔赫纳·德·印第亚斯,位于加勒比海岸的西班牙殖民地新格拉纳达(今哥伦比亚),重要的港口和防御城市,便于从面向太平洋的富有的西班牙殖民地运送物资。这些物资通过陆路,经巴拿马地峡被运输到加勒比海。物资在卡塔赫纳整装并运往古巴岛,最终穿越大西洋到达其最终目的地西班牙。

⑥ 巴西殖民建筑的一个显著特点是,尽管巴洛克式的教堂和其他重要的建筑位于公共广场周围,但看上去彼此分离,这增强了其标志性特征;在欧罗普雷托、马里亚纳、提拉丹蒂、圣若昂多雷、米纳斯吉拉斯州等巴西城市中,随处可见美丽的巴洛克式殖民建筑,证明这里富含黄金和其他矿藏。

⑦ 该名录包括第一座被殖民的城市—厄瓜多尔的基多,以及厄瓜多尔的昆卡,古巴的拉哈巴纳,波多黎各的圣胡安,墨西哥的墨西哥城、普埃布拉和瓜达拉哈拉,危地马拉的安提瓜,巴拿马的巴拿马城,秘鲁的利马和库斯科(这座殖民城市建于前西班牙印加方格网之上,并存在大量石砌的原住民建筑),哥伦比亚的卡塔赫纳、蒙波克斯和波帕扬,巴西的欧罗普雷托和地拉丹蒂,巴拉圭的亚松森等等。

⑧ 此时的西班牙也对菲律宾进行着殖民。在亚洲,殖民地的城市模式和建筑类型与拉丁美洲类似。

⑨ 在殖民地时期,新世界被视为旧世界的试验田;独立后,旧世界又成为新生民主国家的参照。

⑩ 19世纪末,在委内瑞拉的加拉加斯,有轨电车被引入一个叫El Paraso(天堂)的地方,从而促使这里发展成为第一个城市郊区。这里的开发商不仅以他们的房子亲近自然且离城市很近为卖点,还推出一种由金属结构(从欧洲进口)建造、可抵御地震的分离式住宅。

⑪这一时期有着杰出的城市结构和建筑类型的城市有:布宜诺斯艾利斯(当时拉美地区最大的城市,以“拉美的巴黎”而自豪)、蒙得维的亚、里约热内卢、智利圣地亚哥、墨西哥城、拉哈巴纳、波哥大等具有久远殖民史的城市。另有一些正在经历快速经济发展的城市,如巴西的贝洛哈里桑塔、累西腓、阿雷格里港和库里蒂巴,以及阿根廷的拉普拉塔城。

⑫有关最新的拉丁美洲城市化趋势和经济数据,见www.bbvaresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Urbanization-in-Latin-America-BBVA-Research.pdf。

⑬例如,1951年,委内瑞拉加拉加斯总体规划由国家规划委员会制订出来,并得到弗朗西斯·维奥利奇、莫里斯·罗蒂瓦尔和何塞·路易斯·塞特等国际专家的支持。该规划提出按照现代理论,线性地建设城市,通过主要干道和高速公路连接起新城,并进一步引入区划。维奥利奇为加拉加斯制定了第一部现代区划条例,其中所提出的分离式建筑,从根本上改变了首都的城市景观。这类城市法规后来被举国仿效。

⑭1955年,约瑟夫·路易斯·塞特和马里奥·罗曼纳奇共同参与了古巴哈瓦那的总体规划。该规划提出建成区的密集化、城市扩张、新的交通网络和开放空间系统,同时提出对历史城区进行彻底的改造,如今这里已成为世界遗产;例如,出生于德国的建筑师亨蒂·克隆布,曾与弗兰克·劳埃德·赖特一起实习,并与路易斯·康共事过。他在波多黎各的加勒比海岛从事过重要的工作(1946—1966年),包括位于皮德拉斯的波多黎各大学的总体规划及其中许多建筑的设计。

⑮巴西里约热内卢的教育部由勒·柯布西耶设计。在《美籍西班牙人的身份:适应还是采用》的文章中,罗纳尔多·多尔斯·阿尔瓦拉多认为,这座建筑是大城市更新项目的一部分,位于城市的一个显著位置,成为巴西现代化的标志,并激发了众多该地区的此类项目(作者的翻译)。

⑯关于罗伯特·布雷·马克斯的遗产,和他在大型公园设计方面的工作,以及他对拉美景观中植物学、美学和表现方面的观点的更多信息,参见玛利亚·比利亚洛沃斯著《罗伯特·布雷·马克斯的植物园,一个创造性的过程—以委内瑞拉马拉开波植物园为例》(法国,凡尔赛,高等景观学校,2010—2015)。

⑰普兰查特村,由著名的意大利建筑师庞蒂于1950年在委内瑞拉加拉加斯设计,作为普兰查特的住所。庞蒂不仅设计了建筑,还设计了所有的家具、灯具、餐具,以及供展示苗圃里盛开的兰花的器具。引自http://www.gioponti.org/en/archives/work-detail/dd_32990_6074/villaplanchart。

⑱关于拉美现代城市规划的弊端的更多信息,见戴维·加弗努尔著《未来非正规住区的规划与设计:塑造自建城市》。

⑲承担位于布宜诺斯艾利斯的梅尔卡多·德·阿巴斯托斯改造项目的是本杰明·汤普森(Benjamin Thompson)公司及其合作公司,他们于70年代末将美国马萨诸塞州波士顿市废弃的昆西市场改造成广受欢迎的商业、餐饮和旅游综合体,使这处滨海的废弃地起死回生。

⑳关于波哥大恩里克·佩纳洛萨和麦德林塞尔吉奥·法贾多的市政遗产的详细信息,见戴维·加弗努尔著《未来非正规住区的规划与设计:塑造自建城市》第2章。

㉑戴维·加弗努尔的这个在线教学视频中,阐述了新兴非正规城市所面临的挑战,以及采取预见性措施的必要性。

㉒由建筑师丹尼尔·费尔德曼设计的儿童发展中心,瑞加村(哥伦比亚考卡)。这是该地区社会意识建筑趋势的一个实例。该项目获2018年威尼斯双年展拉美青年建筑师一等奖。

㉓这类新项目有:位于智利圣地亚哥的富人区中的两百周年纪念公园和为贫民窟服务的雷纳托·波夫莱特教士河公园,位于哥伦比亚卡塔赫纳克雷斯波,通过缩窄通往机场的城市道路而连接起贫民窟与临近海滩的滨水公园,从机场到城市,以及位于哥斯达黎加圣何塞,沿着对城市形成切割的河谷进行建设的,目前正在实施的鲁塔斯·纳塔努拉斯带状公园。

㉔有关该项目的更多信息,见奥斯卡·格劳尔著《滨海地区的修复》。该项目于2000年获委内瑞拉建筑双年展一等奖。这是该地区第一个针对灾后重建和防洪的绿色基础设施项目,此前,委内瑞拉中部加勒比海岸线被洪水大规模冲毁,造成近30 000人丧生。由于当地政治集权、军事行动和腐败,项目实施两年后被取消。戴维·加弗努尔是该项目负责人。

㉕图1来自墨西哥画家迭戈·里维拉的壁画《特诺奇提特兰的市场》;图2、6、8、13、15由奥斯卡·格劳尔提供,取自《法则,制度和城市形态:委内瑞拉案例研究》,国际微缩胶片大学博士学位论文,1991;图3来自公共领域;图 4、5、14、18来自David Gouverneur;图7引自https://i.pinimg.com/originals/49/c9/75/49c97 5728df081319bd6c144d139cefc.jpg;图9引自https://images.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?p=oscar+niemeyer%E2%80%99s+marquesina+de+baile+pampulhas&fr=yhs-pty-pty_email&hspart=pty&hsimp=yhs-pty_email&imgurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.revistaconstruye.com.mx%2Fimages%2FPAMPULHA_LA_MARAVILLA_DE_LA_ARQUITECTURA_MODERNA_EN_BRASIL6.jpg#id=3&iurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.revistaconstruye.com.mx%2Fimages%2FPAMPULHA_LA_MARAVILLA_DE_LA_ARQUITECTURA_MODERNA_EN_BRASIL6.jpg&action=click;图10引自search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?hspart=pty&hsimp=yhs-pty_email¶m2=0f9998cb-d7aa-4747-91c1-2d3edd114954¶m3=email_~US~appfocus1¶m4=d-ccc1-lp0-bb8-dc2~Chrome~aerial+pictures+of+brasilia~7B6E62A1BA14 FE86940A8E0C889E8B89¶m1=20180803&p=aerial+pi ctures+of+brasilia&type=dc2;图11引自https://images.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?p=aula+magna+de+caracas+phot os+october&fr=yhs-pty-pty_email&hspart=pty&hsimp=yhspty_email&imgurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ideasdebabel.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2017%2F11%2FAu la-Magna-de-la-UCV.jpg#id=0&iurl=https%3A%2F%2Fsmedia-cache-ak0.pinimg.com%2Foriginals%2F35%2 F46%2Fd5%2F3546d5fffc8d0dec6393fff17570da26.jpg&action=click;图12来自宾夕法尼亚大学设计学院档案;图16引自http://magiaenelcamino.com.ar/puerto-madero-delo-obsoleto-a-lo-exclusivo.html;图17、19、20来自Alejandro Echeverri;图21来自Giancarlo Mazzanti;图22来自Daniel Feldman;图23引自https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bc/Parque_Renato_Poblete.JPG/1200px-Parque_Renato_Poblete.JPG;图24来自Aubrey Jahelka,Shuwen,and Maria Altagracia Villalobos;图25引自加拉加斯市中心、委内瑞拉城市文化基金会。.

(编辑/刘玉霞)

1 Introduction:a region of hybrid cultures and multiple influences

Latin America is a region with a high degree of cultural mix and amalgamation of influences as a consequence of different factors:a) its territorial richness,straddling the Atlantic/Caribbean and the Pacific Oceans,extending from North to South over 6,000 miles;including some of the largest mountain ranges,tropical forests,and deserts in the world;b)Being the “New World”,the region to fall under the colonial control of European Imperial powers in the early 15th century;c) the strong influence of the United States during the twentieth century,and more recently of other rising economies.

While these clashes or juxtapositions frequently resulted in the violent imposition of foreign values over local conditions,over time,a rich hybrid cultural pallet was to emerge,affecting all facets of life,including the urban landscapes.Understanding this process may help us envision the challenges that the region still faces,as well as the emerging academic and professional trends.

What follows is a synthesis of the main historical periods that have shaped the hybrid-built scenario of Latin America,including compelling landscape architecture,urban design,and architectural features[1](Fig.1).

2 Pre-hispanic period:cosmogony of territorial systems in harmony with nature

When the European conquest and colonization of the New World began,following the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492,they encountered highly advanced societies that had developed a complex system of territorial links,sophisticated urban layouts,and architectural products[2].

The main areas of cultural and economic development of this period were represented by the Aztec and Maya cultures,of Mexico and Central America,and those of the Inca Empire centered in the Andes Mountains of Peru,Bolivia,and Ecuador.These systems relied upon a rigid social and cosmological hierarchy,fueled by forced labor and slavery.Consequently,the urban spaces and main edifices reflected an organization denoting a divine control of the rulers over the masses.

Early Spanish chronicles describe their first encounters with these civilizations,their urban organization,the infrastructure,and the cleanliness of the cities,the grandeur of the stone-built temples and public spaces;as well as the synchrony of the urban form with local environmental conditions.Cities deployed a sort of early ecological urbanism,allowing them to sustain large-scale urban agriculture,complex irrigation systems,and even sanitation in the urban cores;conditions that were not present in the European cities of this period①.

Such was the depiction of Tenochtitlan,the main Aztec center (currently Mexico City),by conquistador Hernán Cortés,impressed by the magnitude of the city built in a lake,with diked roads that connected it to the shores,a complex system of waterways,and a large extension of aquatic urban agriculture in pods called chinampa,which provided the city with high-yielding crops[3].

The main goal of the Spanish and Portuguese colonization of Latin America was the extraction of natural resources to be sent to Europe,as well as the religious and cultural imposition over the “discovered” lands.For these reasons,the colonization of Latin America resulted in the erosion and destruction of the pre-Columbian cities,and fragile landscapes,replaced by European prototypes.Consequently,there is not much left of this pre-Columbian built legacy other than the outstanding remains of urban layouts and edifices,located in remote locations,abandoned before the arrival of the Europeans,some recently uncovered from the dense tropical forests.

16 阿根廷布宜诺斯艾利斯,马德罗港废弃仓库改造Puerto Maderos,recycling of defunct warehouses,in Buenos Aires,Argentina

The most relevant architectural prototypes of this period are the ceremonial pyramids and monumental ensembles,with ornate stone decorations of Mesoamerica in sites such as Teotihuacan,Chichen-Itza,Palenque,and Tikal,to mention just a few;or the carefully assembled stone walls that configured domestic homes and temples,as well as the stone terraces for urban and agricultural adaptation in the high Andes,as in Pisac,Sacsayhuaman,Ollantaytambo,or Macchu Picchu (Fig.2).

Most of the indigenous populations lived in constructions made of light materials:wood,canes,fibers and earthwork,which over time dissolved into the natural settings.

Important aesthetic references of the architecture and artwork from this period can be found today in the visual arts,particularly in murals,pottery,fabrics,graphic design,sometimes-incorporated in contemporary architecture (Fig.3).

3 The colonial-city:implanting an urban prototype

The Colonial period extended for over three centuries until the first third of the 19th Century,when most Latin-American colonies became independent nations.These cities were the product of the European Renaissance and Baroque periods,a large-scale military operation for rapid territorial occupation and political control.In order to accomplish this task,considered the major urban colonization operation in history,the Spanish Crown,enacted in 1573 a simple set of urban regulations and design criteria that were condensed in a legal instrument called the Ordinances for Discoveries,New Settlements,and Pacification,or Laws of the Indies②.

The main design tool of these Laws was the widespread use of the Cartesian grid,shaping close to 800 Spanish settlements from California to the southern tip of the continent.The colonial urban prototypes were to denote the imposition of the European powers over the local culture (Fig.4).As the first step to the foundation of new towns,vegetation was cleared,—the will of mankind was prevailing over natural forces③—The squares were treated as dry landscapes,used for markets and religious events,exalting the public buildings (churches,municipal buildings,prisons or military facilities) that surrounded them.As Chueca G.and Torres B.said:“The city was to be differentiated from the countryside by the type of activities,the population,and,most importantly,by its geometrical design.[4]”

17 哥伦比亚麦德林,娱乐和科学中心(亚历杭德罗·埃切弗里设计)Parque Explora,in Medellín,Colombia,by Architect Alejandro Echeverri

18 通往西蒙·玻利瓦尔公共图书馆的开放空间(罗赫略·萨尔莫纳设计)Access to Simón Bolívar Public Library in Bogotá,Colombia,by Rogelio Salmona

Laws of the Indies made explicit references to site location,proximity to sources of water,existence of indigenous settlements (which meant that they were fit for habitation),as well as the location and proportion of the foundation square and secondary plazas④.There were also prescriptions recommending the reduction of street widths in sites of hot climate in order for the buildings to cast shade on at least one side of the streets,as in San Juan de Puerto Rico;Cartagena⑤,Colombia;or in Ciudad de Panamá[5](Fig.5).

The Ordinances indicated that the blocks were to be divided into four parcels and assigned to the founders of the settlements.Only in wealthy cities this block-subdivision prevailed,the parcels were quickly subdivided into smaller lots or were partitioned and passed on to the settlers’ descendants.The larger lots and houses of the wealthier groups were located closer to the main plaza,the smaller properties of the less affluent,towards the fringe.

There were prescriptions for the treatment of important civic and religious buildings,but residential and commercial buildings were constructed following the traditions of Spain and Portugal,which in turn were influenced by the Islamic occupation,and thus embedded another layer of cultural hybridization[6-7].The buildings defined continuous street-walls,separating the public from the private realm,organized in a hierarchy of patios serving interconnecting room selimiate ;the more formal towards the front of the lots,and the more domestic and service-oriented towards the rear.Vegetation was introduced in the patios of public and private buildings.The height of the constructions,the number of windows,the use of balconies in multi-level structures,and the decoration of portals of the doors and windows facing the street denoted the social status of the occupants.

The size and richness of ornaments on nonresidential buildings depended on the wealth of the regions;construction materials varied based on the availability of local materials- mainly adobe,compressed-earth thick walls,cane structures with mud pads,stone,or coral rocks in some coastal areas.In areas with a strong presence of indigenous groups,the architecture and artworks incorporated indigenous by local motifs.Cultural hybridization was already taking place in Latin America[7].

Outstanding urban and architectural examples can be found in most Latin American countries,particularly in colonies previously occupied by the more advanced and populated indigenous groups,such as:Mexico,Guatemala,Colombia,Ecuador,Peru and Bolivia;or those that became important cities for the defense of their ports and storage of goods prepared to be shipped to Europe,such as today’s Ciudad de Panama,Cartagena,La Habana or San Juan de Puerto Rico.

Brazil,a very large colony under the domain of Portugal carried out a similar enterprise of foundation of new towns motivated by the same economic and religious reasons as the Spaniards.However,this Empire did not enact urban design guidelines as the Spanish Ordinances.Some cities in Brazil were founded using the urban grid,many others reflected the more organic growth patterns of traditional Portuguese towns.

Outstanding colonial baroque architecture⑥was produced in Brazil today due to the riches of the land,and to the fact that this country avoided a bloody and prolonged war of Independence,since the Portuguese Courts decided to peacefully transfer the capital of the Empire to Brazil in 1807.

Numerous of these cities are today UNESCO World Heritage sites,both in Spanish and Portuguese colonized Latin American Territories⑦.Notable are also the walls and military fortifications that protected the main ports of the mainland colonies and the most important colonial cities in the islands of the Caribbean.

In time,the colonial urban fabrics would produce urban forms and an architectural legacy that are today highly valued by Latin American nations,as symbols of their identity and hybrid culture.The colonial cores are frequently the main areas of the social encounter of these stillstratified societies,hubs of economic activities,and attractors of tourism(Fig.6).

4 The republican period:greening the city

By the 1830’s,most Latin American former colonies had gained independence.Spain was able to retain control of the fortified Caribbean islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico⑧.After almost two decades of bloody and destructive wars,the new Latin American nations would enter a period of legal,economic,cultural,and urban changes.

Open trade with other European nations-particularly with Great Britain,France,and to a lesser degree Germanic states- would impact the new Republics,modifying the patterns of production,manufacturing,exports,and urban landscapes.France became the dominant cultural reference for many Latin American countries,influencing their legal and political systems,and becoming the urban,landscape,and architectural point of reference.It was the dawn of a new period of economic dependency and cultural assimilation⑨.

The new open trade conditions would propel the growth of Latin American cities,introducing new infrastructure such as ports,railroads,roads,and aqueducts,manufacturing areas,as well as service facilities such as hospitals,markets,schools and universities,and military installations.It also led to the emergence of the first social housing programs at the dawn of the Twentieth century.Consequently,the compact colonial cores began to expand,following the urban patterns and architectural styles deployed in Europe[8].These new conditions resulted in significant changes of the Latin American urban landscape,mainly:

1) Rural land was rapidly converted into urban land,igniting a speculative real estate market,and creating a wealthy entrepreneurial class (the former landowners during the Colonial period).An emergent affluent class started relocating to the expanded urban periphery in urban areas –immersed in the green landscape- fleeing from the congestion,and the social problems associated with the traditional urban cores⑩.

2) A new appreciation for landscape features and the greening of cities,as tools of embellishment,reflected in the creation of boulevards and parks as places for social encounters and leisure,and serving as real-estate attractors In contrast to the colonial city,which was non-responsive to the local landscape and cultures,the Republican period can be considered one that exalted territorial,environmental,and botanical aspects (Fig.7).

This period was more experimental and open than the colonial one,adapting European urban and architectural prototypes to local conditions,taking references from different sources,carried out by a wider array of public and private actors,and recognizing the varied local natural settings,and rich botanical pallets;it can be considered the Latin American version of the Garden City and City Beautiful movements.

Many cities tried to emulate Haussmannian Parisian layouts ,sometimes introducing them over existing urban fabrics;in other cases,deploying to urbanize former agricultural land or natural settings[9].Extension of cities and new towns were created to accommodate the emergent economic activities.European architects,engineers,and urbanists were commissioned to carry out these plans and projects,using design principles in vogue at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Examples of this type of European-modeled urban interventions and architectural prototypes can be found in almost every important city in Latin America⑪(Fig.8).

An outstanding example of the period is the Chilean port city of Valparaiso today a UNESCO World Heritage site.This urban center was one of the main ports and commercial centers in the continent.Its adaptation to steep topography,the use of inclined elevators,and its eclectic architecture,make it a unique example of Latin America's post-colonial hybridization (Fig.9).

5 Latin American modernism:adapting principles to place and culture as the region becomes urban

Latin American nations,from the mid-20th century onwards,went through a period of rapid urbanization,modernization,and industrialization,at a time in which the USA had become the dominant economic and military world power.Until then,most Latin American nations were predominantly rural countries.In less than five decades,the percentage of people living in urban centers had equaled or surpassed that of rural areas.Nowadays,Latin America presents the highest percentage of urban population in relation to urban indicators of other regions comprised of developing countries⑫.In nations as Mexico,Cuba,Venezuela,Brazil,or Argentina,with very strong economies at the time,migrants also arrived in great numbers from other Latin American nations and continents,particularly from those decimated during the II World War (Fig.10).

This period of economic bonanza in the region coincided with the widespread acceptance of modernist ideas in city planning and architecture,fostering the rehabilitation of war-torn countries in Europe and guiding the suburbanization trends in the United States and Canada.The changes that were taking place in North America were to have a strong influence on the rest of the continent,through the academic discourse,and by the adaptation of planning instruments and building codes⑬.Latin American cities were experiencing societal,economic,and urban structural transformations similar to the changes that China has experienced over the last two decades (Fig.11).

The region was to produce outstanding examples of contemporary urban design and architecture,following Modern principles(which derived from the Congrés International d’Architecture Moderne–CIAM–) which were intended to be of worldwide application.However,in Latin America,they were adapted to local conditions,and tinted with regional nuances[10],responding to local settings and climate,with a sense of monumentality,powerful urban configurations,emphasis on the design of public spaces,experimental integration of urban design,architecture,landscape architecture,art,and cutting-edge structural design,and,in some cases,reinterpreting features of indigenous,colonial and post-colonial architecture.

19 哥伦比亚麦德林,巴里奥·圣多明各,缆车站和绿廊Metro-cable station and green corridor,Barrio Santo Domingo,Medellín,Colombia

20 哥伦比亚麦德林,巴里奥·圣多明各,儿童嬉戏区和行人天桥Children play area and pedestrian bridge,Barrio Santo Domingo,Medellín,Colombia

21 哥伦比亚麦德林,阿塔纳西奥·吉拉尔多特体育馆(吉安卡洛·马扎蒂设计)Atanasio Girardot Sport Complex in Medellín,Colombia,by architect Giancarlo Mazzanti

The exhibition of Latin American Architecture,held in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 2015,titled —Latin America in Construction—,offered an ample display of outstanding Modern Latin American architecture and city design from the 1950’s and 1960’s.Notable in this exhibit were the large-scale and audacious publicly funded projects.These included social housing developments,parks,university campuses,public schools,administrative centers,hotels,hospitals,fairgrounds,etc.

These projects symbolized the public will and a new sense of pride and identity of countries that were having a prominent economic role at a global scale.The open-migratory trends,receiving qualified professionals,educators,and craftsmen seeking opportunities and fleeing war-torn Europe and even Japan,reinforced the hybrid Latin American cultures,and enriched the quality and diversity of design solutions.

The region was visited by some of the most distinguished designers of the mid Twentieth century,such as Walter Gropius,Jose Luis Sert,Mies van der Rohe,Richard Neutra,Roberto Burle Marx,and many others,who influenced academic and professional practices.These influences transformed academic programs,and professional practices alike,producing projects that were carefully adapted to site and climatic conditions,and incorporating the use of local craftsmanship and materials⑭(Fig.12).

Projects displayed a distinct Corbusian undertone.It has been argued that Le Corbusier’s proposals of a robust and at the same time open,and porous architecture,were more suited for tropical settings than for subtropical areas,where they weathered better,could take advantage of the breezes,and their morphology/geometries were enhanced by intense contrasts of light and shade[11].The Modernist Movement was embraced with such vigor in Latin America that in some countries such as in Brazil its legacy continues to live on,in fluencing contemporary projects⑮(Fig.13).

The most notorious projects of this kind were:the governmental,residential and central business core of Brasilia,the new Brazilian capital,the campuses of Universidad Autónoma de México(UNAM) in Mexico City,and of Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV),in Caracas — all of which today are UNESCO World Heritage sites.An notable example of regional and new town planning is Ciudad Guayana,designed by the Joint Center for Urban Studies of Harvard and M.I.T,and the Venezuelan Guayana Corporation in the 1960’s.It was created to industrialize unpopulated areas ,based on steel and aluminum production.The efforts included the protection of the watersheds and habitats,in order to guarantee hydroelectric energy,and a system of large parks designed in the 1980’s,built in conjunction with large-scale infrastructures,as dams and highways.

Another important contribution of this period is the role of landscape architects,providing compelling public spaces,which still play a major role offering places of leisure where all socioeconomic groups can interact in cities that are today becoming further stratified and spatially segregated.Here we must refer to the pivotal contributions of one of the most prolific landscape architects of the 20th century:Roberto Burle Marx.While Brazilian-born,Burle Marx’s work would have a major influence in Latin America and around the globe,his projects set new directions for the profession and sparked a widespread appreciation for local landscapes and botanical material,breaking with a landscape tradition,which had previously followed foreign European morphological and aesthetic standards.

Burle Marx’s legacy includes the discovery of hundreds of new plant species,during his botanical explorations in Latin America and other continents (Fig.14).

His large parks,such as Ibirapuera in Sao Paulo,Brazil;or Parque del Este in Caracas and the Botanical Garden of Maracaibo,both in Venezuela,are masterpieces of recreational spaces with a profound understanding of botanical structure,morphologies,and performative aspects,with subtle pedagogical undertones,inviting users to appreciate these sites as places for leisure,interaction,and learning⑯.

His world-recognized stone-paved sidewalk of the redesigned street section in Copacabana beach,and the Landfilled Flamengo Park—both on the waterfront of Rio de Janeiro,Brazil—are among the most notorious constructed open spaces of this unique city,exalting the urban and the natural landscapes.His legacy includes close to 2,000 built projects,which in turn influenced the work of other renowned Latin American landscape architects,such as Mario Schjetnan[12]in Mexico,or the Chilean-born Fernando Tábora who worked in Venezuela.

Many of these initiatives were funded by national governments—frequently by highly centralized ones,—and military regimes,which showcased them to demonstrate their “efficiency and dedication to national welfare.” The Modernist design frenzy also had a spillover effect on projects carried out by the private sector in smaller in scale,but very prolific,and equally experimental⑰.It was certainly the golden era of Latin American architecture,urban design,industrial,and graphic design,as well as cutting-edge fine arts explorations.

However,the modernist urban planning heritage in Latin America is far less acclaimed,due to the widespread and standardized application of plans and zoning codes,with the following consequences:

1) The modern planning paradigms conceived the cities as entirely new functional entities,based on real-estate driven operations,favoring single-use developments,connected by a hierarchy of road works,with detached tower-like buildings,drastically modifying the morphology and performance of the cities;many times,leveling entire older areas,and creating new anonymous urban conditions.

2) The application of modernist urban criteria also resulted in urban sprawl,loss of valuable agricultural land and ecosystems,socially and spatially segregated cities,lack of good public places for socialization,and made them auto- and energy-dependent.

3) The emergence of the informal or unplanned city,since the modern urban paradigms did not have mechanisms to accommodate the very lowincome migrants,having no other option other than squatting on non-urbanized land outside of the urban plans (frequently risk-prone sites),resulting in severe inequalities and social/spatial fragmentation⑱(Fig.15).

6 Urban design practices:site-specific responses

The last decades of the twentieth century produced compelling urban design,and site-specific interventions in the region with emphasis on the public realm,urban revitalization,the uniqueness of place,and the appreciation and recycling of sites and buildings of historic significance,in contrast to the generic,spatially indifferent,and tabula-rasa approaches of modern city planning (Fig.16).

Some emblematic projects of this period included the rehabilitation of post-industrial sites.Such is the case of the Puerto Maderos project,which took advantage of port-warehouses and docks,and recycling the also defunct concrete vaulted-structures of the Mercado de Abastos⑲(the central marketplace built in the 1930’s),both for commercial and recreational activities,located in Buenos Aires,Argentina;or the conversion of manufacturing warehouses into a large-scale cultural and performing art center,known as SESC Pompèia,in Sao Paulo,Brazil.

Other initiatives aimed at the creation of large-scale open spaces,as the conversion of a mile-long stretch of an inner-city expressway in Caracas,Venezuela into an avenue reconnecting the city grid (Avenida Bolívar),or the transformation of an equally long traffic-congested avenue into a pedestrian mall (Sabana Grande Boulevard) thanks to the construction the city’s first Metro line,both projects in Caracas.It is also worth mentioning the creation of an important waterfront promenade that opened the city to the estuary of the Guayas River,in Guayaquil,Ecuador,triggering economic activities and becoming a site of intense social interaction.

Other important urban milestones at a metropolitan scale were taking place towards the end of the millennium,thanks to the proactive administrations of architect and city planner Jaime Lerner (Mayor of Curitiba),and architect Cesar Maia(Mayor of Rio de Janeiro),both in Brazil;as well as in Colombia,under the leadership of mathematician and professor Sergio Fajardo (Mayor of Medellín),and during the first administration of the economist Enrique Peñalosa (Mayor of Bogotá) (Fig.17).

As an example,Peñalosa was able to tackle very difficult urban conditions during only 3 years of his mandate,giving upfront priority to the built environment,and proving that good public service could make a big difference in a region accustomed to inefficient,unqualified,and corrupt political leadership.While his managerial take was of a top-down nature,he was able to reposition this capital of close to 9 million inhabitants as a leading regional urban center (Fig.18).

His achievements in Bogotá included:an extensive BRT system which was the first comprehensive mass transit system of the city,250 linear kilometers of enlarged and tree-planted sidewalks and bike lanes,schools for 200,000 students in dozens of new and renovated facilities.He was also able to deliver dozens of new parks,a system of large-scale park-libraries the majority serving the poorest neighborhoods,large-scale subsidized housing projects with emphasis on public spaces and communal facilities,etc.Such initiatives contributed in reducing social disparities and equalizing urban standards throughout the metropolitan area.The city of Bogotá was granted multiple international awards for these accomplishments,his legacy set the stage for ongoing efforts of following administrations to address urban affairs with creativity and vigor⑳(Fig.19).

22 哥伦比亚瑞加村,儿童发展中心(丹尼尔·费尔德曼和伊凡·基尼翁斯设计)Early Childhood Development Center,in Villa Rica,Colombia,by Daniel Feldman and Ivan Quiñones

23 智利圣地亚哥,为贫民窟建造的雷纳托·波夫莱特教士河公园Parque fluvial Padre Renato Poblete,serving low income areas,in Santiago,Chile

7 The informal city:from denial to holistic approaches

Urbanization and modernization in the region were accompanied by flows of rural migrations that could not benefit from formal city planning and real-estate interplay.This led initially to lowincome tenements in the older colonial cores,as the former wealthier residents moved out to new suburbs.Simultaneously,cities experienced the emergence,gradual consolidation,and expansion of unplanned informal settlements in the urban periphery,or on inner city sites,along ravines,steep slopes,and other areas designated in the urban plans as unfit for urbanization.Authorities,academics,and professionals considered first the informal occupations an unwanted new phenomenon that could be stopped and eradicated through social housing projects.They did not realize that the constant in flux of very low-income migrants would create a demand for housing units that could not be supplied by the formal sector,or that these migrants simply could not afford those homes,as they lacked formal jobs and savings.In a few decades,it had become obvious that the informal settlements were there to stay,and that in many cases,had become the dominant form of urbanization.

In countries that had followed a democratic path,these challenged areas also meant votes.Consequently,the public sector began to attend them,first with simple interventions such as providing electricity,water,schools,medical and sport facilities,or paving pedestrians lanes and staircases—and in some cases,painting the facades of homes to give them a better appearance-,and making more visible these public actions,particularly during pre-election periods[13].

Legal reforms were introduced,acknowledging informal urbanism as an integral part of cities,enabling the public sector to respond to their demands,and envisioning technical and managerial mechanisms to do so.

The last decades have witnessed important initiatives for improving living conditions in these settlements.Such projects can be considered -urban surgery-,since they require careful operations on the tight urban fabric to introduce public spaces,improve accessibility,incorporate infrastructure and communal services,or to relocate families living in high-risk areas.To make space for these interventions and minimize social disruption,it was indispensable to provide a relocation housing,within or as close as possible to the original dwellings.Holistic approaches were carried out in Caracas (Venezuela),Rio de Janeiro (Brazil),and Bogotá and Medellín (Colombia) (Fig.20).

Those delivered in Medellín,under the political leadership of mayor Sergio Fajardo,and the technical visions and drive of architect Alejandro Echeverri,have gained world recognition,due to the quality of the urban landscapes and architectural solutions,resulting in astonishing urban change and social benefits,and making the city a world reference for this type of social urbanism21.Attention was given to the poorest,most violent,and vulnerable informal neighborhoods.The projects included the use of aerial gondolas or outdoor escalators as means of mobility,cutting-edge park-libraries,new schools,and cultural facilities,among others.Equally important was the way in which the different components where phased,the modalities of communal involvement and local management,and the provision of cultural activities and maintenance programs.In 2014,the World Urban Forum took place in this once-challenged city (Fig.21).

The positive socio-environmental impacts derived from these holistic plans have certainly influenced the state of the art in academia,professional practice,and political leadership,focusing on the needs of the lower income populations in Latin America and have served as references for initiatives in other continents.

However,Latin America is still ranked as the region with the highest degree of socio-economic inequality[14-15].Informal settlements continue to grow at a further distance from the formal areas,increasing such disparities and aggravating urban performance.Not addressing the growth of the informal city will result in additional environmental and social stress and problems of governance,factors that are already affecting its competitiveness in the global marketplace.

But doing so,is still considered a taboo in Latin America,as if by planning ahead for this inevitable trend was to operate illegally,or to further induce this phenomenon.My own teaching and research focus on how to anticipate and manage the exponential expansion of the informal city,providing criteria,simple and flexible design solutions,and implementation tools,depicting how a preemptive approach can be adapted to different contexts.This is explained in my publication Planning and Design for Future Informal Settlements:Shaping the Self-Constructed City,or its expanded and edited Spanish version Diseño de nuevos asentamientos informales㉑(Fig.22).

8 Socially oriented architectural trends,and new landscape and ecological movements

The recent Biennales of Architecture,Landscape Architecture,and Urbanism in the region have granted many winning prizes to projects addressing compelling social problems,which represent a change in attitude of the academic and professional milieu.Many of the awarded projects resulted from design competitions,allowing young professionals and smaller firms to advance cutting-edge projects with compelling social and environmental agendas.In addition to the morphological-aesthetic aspects,these projects address performative issues such as communal participation in their design phase,construction,and operation,the use of local low-cost and lowmaintenance materials with references to traditional architecture and buildings technologies.There are also new trends,which can be considered a vernacular revival,going back to Pre-Hispanic roots of design and materiality,which frequently result in clashes with commercial firms that supply construction materials and technologies.Colombia is pioneering this type of initiative㉒(Fig.23).

There have been important recent initiatives in the region creating public spaces,parks,and promenades,and addressing ecological issues,as well as morphological,water management,performative,and botanical aspects.Examples of this trend can be found in cities of Chile and Colombia㉓.

Risk reduction projects have been carried out,such as after the torrential flooding which destroyed the Caribbean shore of Caracas,Venezuela,in the year 2000㉔(partially executed);the rehabilitation of different towns hit by a quake and strong tsunami in Chile in 2017 (projected);the reconstruction of informal settlements on higher elevations of Valparaiso affected by forest fires in 2014 (partially executed);or coping with widespread damage of devastation by two consecutive hurricanes in Puerto Rico in 2017,(projects underway).These initiatives have forced governments,institutions,academia,and professionals to think in a more holistic and out-of-the-box manner.

It is becoming evident that climate change and lack of environmental planning is taking a toll in a region prone to the impact of forces of nature,or coping with sea level rise,where the lower income communities are frequently the most vulnerable (Fig.24).

24 厄瓜多尔查南加斯镇重建的咨询建议(宾夕法尼亚大学设计学院奥布里·贾赫尔卡和叶舒文设计)Proposal for the rehabilitation of Chamangas,Ecuador,by Aubrey Jahelka and Shuwen Ye,Department of Landscape Architecture,University of Pennsylvania

However,less has been done in terms of ecological restoration,green infrastructure,water management,increasing permeability,remediation,or addressing climate change and urban agriculture,income-generating activities,etc.,aspects that are still considered in most Latin American countries as requiring high costs and complex management.Despite the surge and vibrancy of landscape architecture practices during the second half of the Twentieth century,Landscape Architecture is usually taught today as courses or in master programs within architecture schools.Some,academic institutions in the region as well as some North American and European institutions interested in Latin America,are playing a pivotal role in exposing students to these issues and will surely prepare a generation of young professionals and leaders that will incorporate them into their practice (Fig.25).Despite the regional diversity and rich biodiversity of Latin America,exponential urban growth continues to erode fragile ecosystems and valuable agricultural land.Urban and conservation practices are still at odds.

9 New challenges

The dawn of the new century can be considered a period of economic and political forces at a global scale,with strong repercussions in the Latin American urban landscape.Notable is the influence of new technologies,large corporations and franchises operating worldwide,and the investment and political relations in the region or China,Russia,and Iran in urban-related fields as infrastructure,transportation and housing.

From a morphological-territorial point of view,the urban landscape of the colonial period was shaped by the adoption and repetition of foreign urban principles and building typologies as compact and pedestrian-friendly urban scenarios.The Republican,the Modern,and the Post-Modern urban design and ecologically-driven periods -as well as the current city planning standards and development trends- resulted in a multiplicity of urban forms,as the region became predominately urban,and cities expanded exponentially.The result has been a mosaic or composite of constructed landscapes that coexist,juxtapose,and transform,frequently adapting to local conditions,and producing compellingly Latin American products.

25 委内瑞拉加拉加斯,佩塔雷—拉乌尔维纳的正规和非正规的城市景观The formal/informal,Petare-La Urbina,in Caracas Venezuela

The hybrid nature of Latin America makes the region a sponge for receiving different influences and,a fertile ground for adaptation and experimentation.The rapid economic growth,modernization,industrialization,and urbanization processes that Latin America experienced from the mid Twentieth century on,was carried out following foreign models.Although these foreign models resulted in the distortion and erosion of natural systems,as well as of urban,architectural patterns,and cultural landscapes,in time,they were adapted and re fined,and thus became more in tune with local conditions.

However,the most recent layers of borrowed urban and architecture references—of a global nature—tend to be more generic,inducing sprawl,social segregation,and identity loss.The shopping malls,business centers,and office complexes in Santiago de Chile,Bogotá,Sao Paulo,or Mexico City are not that different from their Asian counterparts,which in turn mirror those in North America and Europe.The proliferation of largescale developer-driven gated communities is a common feature in the ever-expanding urbanizing territories of Monterrey,Barranquilla,Maracaibo,or La Paz.While sold in the name of safety,they are increasing insecurity in the public realm,while promoting social segregation,urban sprawl,cardependency,discouraging people from socializing in public spaces,and straining city management.

As Daniel Feldman describes,“the urban and architectural state of the art in Latin America is also being influenced by the role of globalized firms,offering governments in the region standardized and prescriptive urban design/urbanization guidelines,ignoring local conditions.Such documents and prepackaged solutions are frequently taken by the local authorities as a technical and financial justification to support large scale urban operations,resulting in projects dependent on foreign technologies and investments” (Author’s translation from a conversation with the Colombian architect Daniel Feldman).

Despite the rise of the region’s GDP,the Millennia has experienced a strong political polarization (surely as a consequence of socioeconomic disparities),witnessing leftwing-militarized movements,and extreme rightwing movements,worrisome political fractures,promotin social divisions by means of populism,and creating cultural and territorial barriers within and among nations (perhapd not that different from similar trends in the United Stated,and in Europe,Asia and Africa).

There is still a complex socio-economic and environmental agenda pending in the region,which demands being more selective,critical,and adaptive of foreign influences,and the development of new urban,landscape and architectural prototypes.The region needs to further rely on solutions that emerge from within,anchored on applied research,academic training,and project/performative solutions,as innovative as those advanced during the modernist era,or that have emerged more recently dealing with the challenges of the informal city.

The rich,hybrid,and experimental urban,landscape,and architectural pallet of Latin America —and the region’s ability to receive foreign influences,adapt them to local conditions,and favor solutions with a distinct and diverse identity,may serve as references for other emergent economies and rapidly urbanizing nations that are struggling to respond to contemporary challenges without ignoring or deleting their own rich historic legacies.

Acknowledgement:

I appreciate the contributions of Oscar Grauer,Nick Pevzner,Ishaan Kumar,and Heryk Tomassini.

Notes:

① Mario Schjetnan,a distinguished Mexican Landscape Architect has done ample research on traditional practices of this nature as sources for contemporary design.

② This Royal Document known as Las Leyes de Indias(Laws of the Indies) constitutes urban design guidelines for the planning of new towns formalized in written rules and regulations.It provided legal status and structure to common practices,providing homogeneity to the foundation of new towns.

③ The clearing of the land was a common practice,but it was not explicitly included in the Ordinances.

④ “The Plaza should be a square or rectangular,in which case it should have at least one and a half its width for length inasmuch as this shape is best for fiestas in which horses are used and for any other fiestas that should be held”,and “the dimension of the plaza should be proportionate to the expect importance of the towns that were to be founded”.These were the type of dispositions included in the Ordinances.

⑤ Cartagena de Indias,located on the Caribbean coast of the Spanish colony of Nueva Granada (current Colombia),was a major port and walled/fortified city,which allowed for gathering products arriving from the rich Spanish colonies facing the Pacific Ocean.These goods were transported by land through the Panama Isthmus to the Caribbean Sea.In Cartagena,the goods were here secured and prepared to be sent to the Island of Cuba,before crossing the Atlantic to Spain,their final destination.

⑥ A distinct feature of Brazilian Colonial architecture is that the Baroque churches and other important edifices,while located adjacent to public spaces,they appear as detached objects,enhancing their iconic character;Outstanding Brazilian Baroque colonial architecture can be found in the cities of Ouro Preto,Mariana,Tiradentes,Sao Joao do Rei,in the State of Minas Gerais,an area that was rich in gold and other minerals.

⑦ This list includes cities such as Quito,the first urban center to receive such denomination,and Cuenca both in Ecuador,La Habana in Cuba,San Juan de Puerto Rico,Mexico City,Puebla and Guadalajara in Mexico,Antigua in Guatemala,Panamá City in Panamá,Lima and Cuzco in Peru (this colonial city was built over the Pre-Hispanic Inca grid and indigenous stone constructions);Cartagena,Mompox,and Popayán in Colombia;Ouro Preto and Tiradentes in Brazil,Asunción in Paraguay,and many others.

⑧ Spain also was able to retain at this point in time of The Philippines.In this Asian domain,the Colonial urban patterns and architectural typologies were similar to those deployed in Latin America.

⑨ During the Colonial period,the New World was seen an experimental ground of how the Old World could be;after Independence,the Old World became the source of reference for the emerging Republics.

⑩ In Caracas,Venezuela,the first suburban areas appeared towards the end of the Nineteenth century,facilitated by the introduction of streetcars in an area Called El Paraíso (Paradise).The developers of this district,besides marketing the benefits of -living in nature but close to the city-,also informed about the advantages of residing in detached residences built with metal structures (imported from Europe),which would resist earthquakes.

⑪Cities with outstanding urban configurations and architecture of this period include:Buenos Aires (the largest city in the region at the time,which took pride in nicknaming itself the Paris of Latin America),as well as in Montevideo,Río de Janeiro,Santiago de Chile,México City,La Habana,Bogotá,etc.,cities that had a solid colonial tradition or that were experiencing rapid economic growth.Among the most notable new cities of this period are:Belo Horizonte,Recife,Porto Alegre,and Curitiba in Brazil,and Ciudad de La Plata in Argentina.

⑫For recent data of urbanization trends and economic data in Latin America,see www.bbvaresearch.com/wpcontent/uploads/2017/07/Urbanization-in-Latin-America-BBVA-Research.pdf.

⑬As an example,in 1951 the Master for Caracas,Venezuela was presented,by the National Planning Commission,and supported by international experts as Francis Violich,Maurice Rotival,and José Luis Sert.The Plan proposed the linear growth of the city following modern principals,the creation of new sub centers connected by large avenues and freeways,and the introduction of zoning.Violich was to produced the first modern zoning ordinances for Caracas,which envisioned detached edifices with setbacks,radically transforming the urban landscape of the capital city.This type of urban codes was to be emulated throughout the country.

⑭Josep Lluis Sert and Mario Romanach worked together in the Master Plan of Havana,Cuba in 1955.The plan envisioned the densification of existing areas,the city expansion,a network of new vehicular links,and a system of opens spaces.It also proposed a radical transformation of the historic district,today a UNESCO World Heritage site;For instance,German born,Architect Henty Klumb,who had interned with Frank Lloyd Wright,and worked with Louis Khan,did important work in Caribbean Island of Puerto Rico(1946 to 1966),including the Master Plan for the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras,and many of its buildings.

⑮The Ministry of Education in Rio de Janeiro,Brazil was designed by Le Corbusier.In the article written in Spanish American Identity:Adaption or Adoption,Ronaldo Dobles Alvarado posits that this building,being part of larger urban renewal project and located in a prominent site of the city,became an icon fort the modernization of Brazil,and inspired numerous projects of this type in the region(Author’s translation).

⑯For ample information on the legacy of Roberto Burle Marx,and his work on large public parks,and his views on botanical,aesthetic and performative aspects of Latin American landscape architecture refer to María Villalobos,“The Botanical Garden of Roberto Burle Marx as a creative process.The case of the Botanical Garden of Maracaibo,Venezuela”,Ecole Nationale Superior du Paysage,Versailles,France,2010—2015.

⑰Villa Planchart,designed by renowned Italian Architect Gio Ponti in the 1950’s in Caracas,Venezuela,was commissioned by the Planchart facility to be their residence.Ponti was asked not only to design the house but also all the furniture,lighting fixtures,cutlery,and elements to display blooming orchids from the property’s nurseries.http://www.gioponti.org/en/archives/work-detail/dd_32990_6074/villa-planchart.

⑱For further information on the negative impacts of modern urban planning in Latin America see David Gouverneur,Planning and Design for Future Informal Settlements:Shaping the Self-Constructed City.

⑲There reconversion project of the Mercado de Abastos of Buenos Aires was carried out by the firm of Benjamin Thompson and Associates,who in the late 70’s converted the abandoned Quincy Market of Boston,Massachusetts,USA into a popular commercial and restaurant venue and tourist destination,acting as a catalyzer for the transformation of the defunct waterfront district.

⑳For information of the legacies of the municipal administrations of Enrique Peñalosa in Bogotá,and Sergio Fajardo in Medellín,see David Gouverneur,Planning and Design for Future Informal Settlements:Shaping the Self-Constructed City,Chapter 2.

㉑This online education video by David Gouverneur offers a synthesis of the challenges of the emerging informal settlements,and the advantages of acting in preemptive manner:www.coursera.org/lecture/designing-cities/rapidurbanization-and-informal-settlements-G5jjZ.

㉒The Centro de Desarrollo Infantil El Guadual,Villa Rica(Cauca,Colombia),designed by architect Daniel Feldman,is an example of recent socially-minded architectural trend in the region.This project received the first prize in the category of Young Latin American Architects of the Venice Biennale 2018.

㉓Among these new projects we can include:the Parque Bicentenario in an affluent community,and the Parque Fluvial Padre Renato Poblete serving low income areas,both in Santiago de Chile;or the waterfront park in Crespo,Cartagena,Colombia that connects a low-income district to the neighboring beaches by means of depressing the main entrance road to the city from the airport,and the ambitious Rutas Naturbanas linear park system currently being developed in San Jose de Costa Rica,along the deep ravines that segment its metropolitan area.

㉔For further information on this project see The Rehabilitation of the Littoral Central,edited by Oscar Grauer,Todmann Editores,Caracas,2000.This project received the first prize in the Venezuelan Architecture Biennale of 2000.It was one of the first green infrastructure projects in the region,dealing with post-disaster recovery and flood control,following massive destruction of the central Caribbean shoreline of Venezuela caused my torrential flooding resulting in close to 30,000 fatalities.Political centralization,militarization and corruption led to the dismissal of the projects after the first two years of its implementation.David Gouverneur was project manager of this project.