入坑:两支交响乐团为排演歌剧走进乐池

文:司马勤(Ken Smith) 编译:李正欣

“其实,乐团只分两种,”美国作曲家兼乐评人维吉尔·汤姆森(Virgil Thomson)曾经写道,“不朽的与纯粹功能性的。”根据他的思维,分在一边的是维也纳爱乐乐团、伦敦交响乐团、克利夫兰管弦乐团等“重量级大腕”;另一边的就是众多的市立与地区交响乐团,还有那些带有教育使命的音乐学院乐团。

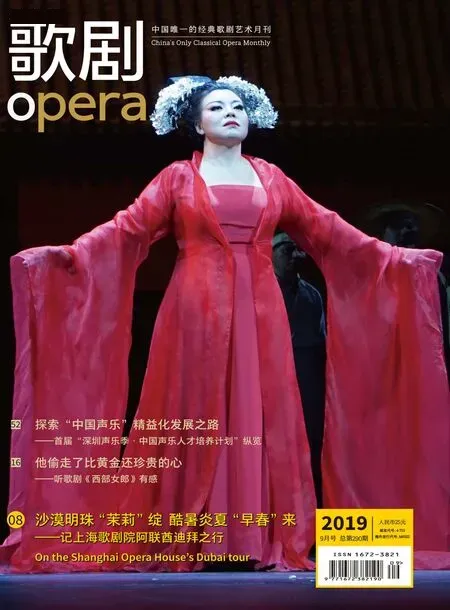

莫扎特音乐节搬演的科斯基的《魔笛》剧照

我也将交响乐界分为两组,但我的界定条件却不一样。一边厢是经常演奏协奏曲与交响乐的团队;另一边厢是经常在乐池里“干活”的歌剧院乐团。大家都跟从指挥奏乐,但除了这个表面上的共同点以外,这两类乐团的架构与组织不同,考虑的音乐细节更有着天壤之别。

我隐约已经听到异议了。你或许会说:到了今天,众多交响乐团不是在每个演出季里都会演一两套歌剧吗?很多歌剧院的乐团不是都会策划属于自己的音乐会系列,可以坐在舞台中央演奏吗?我同意这两个叙述,但它们也为我的观点提供了佐证。你只需五分钟的时间,就可以听得出乐手们是否离开了自己熟悉的环境。演奏交响乐时无法呈现曲式与结构的多支歌剧院乐团,与演奏歌剧时无法配合歌唱家“呼吸”的多支交响乐团,可谓两者不相上下。

东京新国立剧场2019年上演的《图兰朵》剧照

今年7月,我在世界两个地方看了两场歌剧演出。它们唯一的共同点是,乐池里团队的专长是演奏交响乐。我先看了莫扎特音乐节乐团(Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra)的演出。这帮职业乐手每年夏季都会聚首在林肯中心——莫扎特音乐节到了今天,是林肯中心最长寿的夏季演出系列。本年度的音乐节搬演巴里·科斯基(Barrie Kosky)执导的《魔笛》(The Magic Flute)。过了不到一周,我看了亚历克斯·奥洛(Alex Ollé)为东京新国立剧场夏季音乐节执导的《图兰朵》新制作。在东京的乐池里演奏的,是巴塞罗那交响乐团。两场演出给了我很不一样的体验。

《魔笛》是柏林喜歌剧院总监科斯基与1927剧团(一个多媒体剧团)合作的成果,今年秋天将亮相澳门国际音乐节与高雄卫武营艺术文化中心。这版别开生面的、混合动画投影与现场演出的《魔笛》于2013年在洛杉矶歌剧院举行美国首演,当年的观众十分受用。到了今年,这个制作才有机会移师至东海岸的纽约市。为何如此?原因可能是在大部分古典音乐策划人的眼中,这版《魔笛》未免过于激进;但对于前卫的艺术策划人来说,恐怕又过于保守(因为套用的音乐来自莫扎特的手笔)。可是,自从勇于冒险的林肯中心艺术节“寿终正寝”之后,莫扎特音乐节顺理成章地承继了那些新颖的、跨界的演出项目。

以上这一切让我们明白,为什么纽约市7月的各种表演艺术中一票难求的演出,竟然发生在曾被《纽约时报》贬低为“灵魂的空调”的莫扎特音乐节。虽然这是莫扎特音乐节首次搬演歌剧制作,科斯基的《魔笛》还是受到了某些传统主义者的批评——比如说《纽约观察者》(New York Observer)乐评人詹姆斯·乔丹(James Jorden)将其称为“杰作被沦为卡通动画”。

包括我在内的大部分观众却不同意这个评价。科斯基与联合导演苏珊·安德拉德(Suzanne Andrade)及动漫艺术家保罗·巴利特(Paul Barritt,他的视觉风格没有太多“卡通”元素,反而是参考了历史电影的概述,尤其是德国表现主义)在两方面取得了辉煌的成功。大体上,他们把莫扎特的人物类型(character-types)——坦白说,在莫扎特的年代,这些人物类型早就被规范了——清晰地连接至早期无声电影(默片)的人物类型上。帕帕基诺这个角色绝对可以由查理·卓别林(Charlie Chaplin)扮演——更胜任的人选是巴斯特·基顿(Buster Keaton);帕米娜则非露易丝·布鲁克斯(Louise Brooks)莫属。从戏剧最基本的文本角度来看,这个制作解决了《魔笛》一诞生就令人苦恼的如何平衡演唱段落与对白的问题。导演通常有几个选择:一、用原本的德语唱词与对白;二、唱词与对白都翻译成本地语言;三、保留德语唱词,对白却翻译成本地语言。科斯基的班底引进了新的选择:把对白提炼为间幕字卡,犹如默片一样,将精简的文字投影在大幕上。即使不加上别的效果,这一次制作出的《魔笛》犹如那些备受追捧的好莱坞默片。

莫扎特音乐节搬演的科斯基的《魔笛》剧照

不过,我或许应对乔丹的评语表示一半的赞同,因为他注意到科斯基的制作“比现场演员更有价值”,虽然他没有提到,演出绝大部分的问题都落在演员上。奥黛丽·卢娜(Audrey Luna)饰演的夜后比较特殊:她在台上六神无主,可能因为演出前几个小时她才接到电话,得补上身体不适的克里斯蒂娜·波利西(Christina Poulitsi)的空缺。朱利安·贝尔(Julien Behr,饰演塔米诺)与罗迪安·波戈索夫(Rodion Pogossov,饰演帕帕基诺)的格格不入更能说明问题。贝尔在舞台上显得庄重,就像贵族一般——可惜或多或少地被巴利特的动画所忽略。波戈索夫在动画的框框里像个男主角一样,只可惜他每次开口都走调。

当晚最弱的环节却出现在乐池里,乐队显得处处都达不到其惯有的水平。指挥路易·朗格雷(Louis Langrée,他曾公开承认,自己从来没有指挥过《魔笛》)控制速度还算可以,但无法让歌剧的音乐抑扬顿挫,也无法让感情层面更加深刻。乐团的演出中规中矩,更像处理协奏曲或交响作品一样。但每当遇上演奏富有叙事性的段落时,就显得被分散了注意力,完全抓不住重点。林肯中心大卫·科赫剧院的音效差劲,基本上跟改装前(及改名前)的纽约州立剧院没什么区别。令人遗憾的声学效果是从前纽约市立歌剧院不那么美好的回忆之一。

东京新国立剧场2019年上演的《图兰朵》剧照

几天后,1.3万公里以外,我走进了另一个完全不同的世界。亚历克斯·奥洛在东京执导的《图兰朵》没有任何卡通色彩。奥洛曾在悉尼歌剧院把威尔第的《假面舞会》变成奥威尔式噩梦的那种反乌托邦情感,这一次套用在普契尼的身上。原来神话式的中国背景变成了卡夫卡的《城堡》,更添上埃舍尔(M.C. Escher)的视觉效果。奥洛的设计团队——阿尔方·弗洛雷斯(Alfons Flores)负责布景、卢克·卡斯特尔斯(Lluc Castells)负责服装、乌尔斯·索尼鲍姆(Urs Schönebaum)负责灯光——整个制作摒弃了中国红与中国金,选用了深浅灰色为主视觉,把传说中的中国宫廷描绘成日本幕府的格调。

这种处理手法也许旨在刻意增强日本观众的共鸣。坦白说,灰色调与制作的整体效果相吻合。艾琳·特奥林(Iréne Theorin)饰演的图兰朵公主,一开始的声线就像冰墙那么冷酷。随着故事的进展,她的嗓音慢慢融化。特奥多尔·伊林凯(Teodor Ilincai)饰演的卡拉夫融合了强度与精准度,王子那种血气方刚的冲动消失了,取而代之的是出人意料的冷静和面对强权压迫下的那种工于心计。朝中三位大臣(平、庞、彭)分别由桝贵志(Takashi Masu)、与仪巧(Takumi Yogi)与村上敏明(Toshiaki Murakami)饰演。组合的喜剧节奏很出色,虽然某些情节一点都不幽默(他们要办的差事,包括给向图兰朵提婚失败的男士挖坟墓)。整个忧郁的氛围与阿尔法诺完成的音乐相配合,亦配合奥洛把故事转向更灰暗的视野。

东京新国立剧场、藤原歌剧团合唱部与滋贺县立艺术中心琵琶湖音乐厅合唱团共同参与了这版《图兰朵》制作。他们厚重的发声与故意抑制的感情宽度,与独唱相辅相成,营造出来的效果与偌大的布景及舞台上有限的色调相得益彰。最细腻的音乐演绎来自乐池,这一现象耐人寻味:东京新国立剧场自成立以来,搬演过不少世界级演出及令人佩服的制作。可是时至今日,剧场还没有自己的“驻院”乐团——要解决这个问题相当简单,因为大野和士(Kazushi Ono)身兼东京新国立剧场艺术总监,也是巴塞罗那交响乐团的音乐总监。

莫扎特音乐节搬演的科斯基的《魔笛》剧照

很明显,普契尼不是莫扎特,这两位音乐巨匠的风格有着截然不同的差别。我们甚至可以争论《图兰朵》是否算得上是普契尼的作品,毕竟这部他毕生最后(且未完成)的作品也是他最复杂的创作。如果说《魔笛》把莫扎特最推崇的音乐元素融合在一起,那么普契尼在《图兰朵》的创作过程中,努力不懈地探索着艺术新领域,最终以作曲家的后期浪漫主义风格影响了20世纪。从乐队的第一拍开始,大野大师熟知乐谱的要求,凸显了如室内乐般的透明度,也营造出百分百繁茂的浪漫情怀——甚至刻意突出某些不协调的和声。其实,这场演出彰显了这支卓越的交响乐团处理音乐方面的细致技巧,平常在歌剧院乐池中很难听得到。他们对于音乐的要求完全没有在戏剧性上打折扣。

让我们回到汤姆森的定义上:莫扎特音乐节乐团的演出只能说刚刚合格。朗格雷忽略了普契尼与莫扎特两位作曲家毕生最后一部舞台作品的共同点:音乐的发展不是根据什么格式或曲式,而是努力贴近舞台上的故事进展。大野大师让歌唱家引领着他,在整场《图兰朵》里时刻跟随着歌唱家呼吸的韵律。我突然有个冲动:倘若刻意让时光倒流,重回那场科斯基的《魔笛》,但换上巴塞罗那交响乐团在乐池里,效果会怎样?

“There are really two kinds of orchestras,” the American composer and critic Virgil Thomson once wrote, “the monumental and the directly functional.”By his reckoning, you have heavyweights like the Vienna Philharmonic, the London Symphony and the Cleveland Orchestra on one side; across the aisle, you find hundreds of municipal and regional orchestras, as well as conservatory ensembles with an educational mission.

I, too, divide the orchestral world into two groups,but my categories are rather different. In one camp are the bands that regularly play concertos and symphonies; in the other are operatic ensembles that spend most of their time in a theatre pit. Both make similar sounds and follow a guy in front waving a stick,but beyond that they are quite distinct organizations with entirely different musical priorities.

I can hear the grumbling already. Don’t most symphony orchestras play at least one opera every season? Don’t many opera orchestras have their own concert series where they actually sit center stage? Well…yes, on both counts, but that often proves the point. You generally need only about five minutes to tell when an orchestra is away from its usual setting. For every opera orchestra that delivers a formless, shapeless symphony performance you’ll find a symphony orchestra with no idea of how to“breathe” with a singer’s musical line.

In July I found myself attending two very different opera productions in opposite corners of the world,the only thing they had in common being that the pit was occupied by a symphonic ensemble. The first was the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra, the seasonal house band of Lincoln Center’s longestrunning summer event, performing in Barrie Kosky’s production ofThe Magic Flute; the second was Alex Ollé’s newTurandotthat opened the summer festival at the New National Theatre, Tokyo, with the Barcelona Symphony Orchestra in the pit. The results could hardly have been more different.

东京新国立剧场2019年上演的《图兰朵》剧照

The Magic Flute, the brainchild of Komische Oper intendant Kosky and the multimedia theatrical troupe 1927—a production coming to Asia in October to open the Macau International Music Festival and Kaohsiung Center for the Arts in Weiwuying—had its US premiere back in 2013 at the Los Angeles Opera, where its mix of live performance and projected animation found a receptive audience. It was a long time coming to New York, though, being too radical for most classical organizations and too conservative for the avantgarde folks (it was, after all, still Mozart). But since the demise of the more venturesome Lincoln Center Festival, Mostly Mozart has inherited many multidisciplinary projects that fall well outside its original brief.

莫扎特音乐节搬演的科斯基的《魔笛》剧照

All of which explains why the city’s hottest ticket that month was being presented by a festival theNew York Timesonce branded “air-conditioning for the soul.” Despite being Mostly Mozart’s first fully staged opera, Kosky’sFlutestill offended traditionalists likeNew York Observercritic James Jorden, who accused it of “reducing a masterpiece to a cartoon.”

Most viewers, myself included, felt differently.Kosky, his co-director Suzanne Andrade and animator Paul Barritt (whose visual style was less a “cartoon” than an overview of historic cinema,particularly German expressionism) succeed brilliantly on two fronts. Broadly, they draw a clear line between Mozart’s character-types—which,frankly, were rather well established even in his own time—to familiar repertory character-types in silent film. Papageno could easily be played by Charlie Chaplin—or even better, Buster Keaton; Pamina was definitely a Louise Brooks type. On more rudimentary dramaturgical level, the production solves an age-old problem in balancing the show’s sung and spoken text. Directors generally have a choice of (a) singing and speaking in the original language, (b) singing and speaking in the language of the audience, or (c) singing in the original German while speaking in the audience’s vernacular. Kosky and Co. add a completely new option: distilling spoken text to a bare minimum and presenting it as intertitle projections like a silent film. If nothing else, it presentsFluteas the Hollywood blockbuster of its day.

I will, though, give Jorden half a point for noticing that Kosky’s production was “far more rewarding than [the] live performers,” though he somehow failed to note that the problem lay mostly with performers. Audrey Luna’s Queen of the Night was a special case, her lack of focus probably due to having gotten the call to replace Christina Poulitsi only a few hours before. The disconnect between Julien Behr’s Tamino and Rodion Pogossov’s Papageno was more telling. Behr was dignified and stately—and more or less ignored entirely by Barritt’s animations. Pogossov, framed constantly in the projections as the star of the show, could barely sing in tune.

But the weakest link that evening was in the pit,with the orchestra revealing its limitations at every turn. Conductor Louis Langrée (who admitted that he had never conducted the work before) kept tempos at a serviceable clip, but neither reached for its emotional heights nor plumbed its depths. The playing was the kind of serviceable approach that gets through a concerto or a symphony but treats text and narrative as if they were distractions rather than the key point. It also didn’t help that Lincoln Center’s current David Koch Theater is basically still the old New York State Theater, whose regrettable acoustics were one of the less fond memories of the old New York City Opera.

东京新国立剧场2019年上演的《图兰朵》剧照

A few days and 8,000 miles later came a different world entirely. There was nothing cartoonish about Alex Ollé’sTurandotin Tokyo. The same dystopian sensibility that turned Verdi’sMasked Ballinto an Orwellian nightmare at the Sydney Opera House now reinvented Puccini’s mythical China more or less like Kafka’sCastleas rendered by M.C. Escher.Ollé’s design team (sets by Alfons Flores, costumes by Lluc Castells, lighting by Urs Schönebaum)shunned the usual reds and golds for gradations of gray, painting its mythical Chinese dynasty rather as a Japanese shogunate.

That may have helped the production resonate with the Japanese audience, but frankly it also had to do with performances that were very much in tune with the production. Iréne Theorin’s Turandot opened the evening with an icy wall of sound that appropriately thawed during the course of the evening. Teodor Ilincai’s Calaf was an equal blend of power and precision, trading the character’s usual red-blooded impulsiveness for a surprisingly cool and calculating challenge to the powers that be. Takashi Masu’s Ping, Takumi Yogi’s Pang and Toshiaki Murakami’s Pong played the trio of ministers with superb comic timing, despite some highly uncomic overtones (their duties included digging the graves of Turandot’s failed suitors). The somber atmosphere remained musically rooted to Alfano’s completion of Puccini’s score while bending the story toward Ollé’s darker vision.

莫扎特音乐节搬演的科斯基的《魔笛》剧照

A combined chorus from the NNTT, Fujiwara Opera and Biwako Hall squarely matched the principal singers both in weighty vocalism and restricted emotional range, a combination rather mirroring the imposing dimensions and limited color palette of the visual design. Any musical nuance that evening emanated primarily from the orchestra pit,which highlights an intriguing point: The National Theatre has a history of quality opera with worldclass performances and impressive production values. What they do not have, however, is a resident orchestra—a problem easily solved when NNTT music director Kazushi Ono is also the music director of the Barcelona Symphony Orchestra.

Puccini is obviously not Mozart, their music being imbued with contrasting stylistic values.Turandot, one could argue, is not even Puccini, his final (unfinished) score being ultimately his most sophisticated. WhereFlutefuses together all the musical elements Mozart held dear,Turandotcharts new artistic ground, with Puccini finally entering the 20thcentury on his own late-romantic terms. Right from the beginning, Ono was supremely in touch with the score’s demands, drawing expansive sonic contrasts from chamber-like transparency to full romantic lushness—even embracing the occasional dissonance. It was a performance, in fact, fully worthy of a symphony orchestra, with an attention to detail rarely heard from a theater pit. And yet,none of this was at the expense of the drama.

Getting back to Thomson’s definition, the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra was functional, but just barely. Langrée missed the one element that Puccini and Mozart’s final stage works share, which is that the music unfolds not in strict formal design but rather in conjunction with the story on stage. Ono, on the other hand, let the singers be his guide and never once deviated from the pulses and lilts in the singers’breath. It made me want to turn back the week and reset Kosky’sFlutewith Barcelona in the pit.

东京新国立剧场2019年上演的《图兰朵》剧照