Is there an association between Helicobacter pylori infection and irritable bowel syndrome? A meta-analysis

Qin Xiang Ng, Nadine Xinhui Foo, Wayren Loke, Yun Qing Koh, Vanessa Jing Min Seah, Alex Yu Sen Soh,Wee Song Yeo

Abstract BACKGROUND Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a prevalent and debilitating gastrointestinal condition. Research has reported persistent, low-grade mucosal inflammation and significant overlaps between patients with IBS and those with dyspepsia,suggesting a possible pathogenic role of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in IBS. This study therefore aimed to provide the first systematic review and meta-analysis on the association between H. pylori infection and IBS.AIM To investigate the association between H. pylori infection and IBS.METHODS Using the keywords “H. pylori OR Helicobacter OR Helicobacter pylori OR infection” AND “irritable bowel syndrome OR IBS”, a preliminary search of PubMed, Medline, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Science, Google Scholar and WanFang databases yielded 2924 papers published in English between 1 January 1960 and 1 June 2018. Attempts were also made to search grey literature.RESULTS A total of 13 clinical studies were systematically reviewed and nine studies were included in the final meta-analysis. Random-effects meta-analysis found a slight increased likelihood of H. pylori infection in patients with IBS, albeit this was not statistically significant (pooled odds ratio 1.47, 95% confidence interval: 0.90-2.40,P = 0.123). It must also be acknowledged that all of the available studies reported only crude odd ratios. H. pylori eradication therapy also does not appear to improve IBS symptoms. Although publication bias was not observed in the funnel plot, there was a high degree of heterogeneity amongst the studies included in the meta-analysis (I2 = 87.38%).CONCLUSION Overall, current evidence does not support an association between IBS and H.pylori infection. Further rigorous and detailed studies with larger sample sizes and after H. pylori eradication therapy are warranted.

Key words: Irritable bowel syndrome; Functional; Helicobacter pylori; Infection; Metaanalysis

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common gastrointestinal (GI)disorders, characterized by chronic abdominal pain and a change in the frequency or form of stool[1]. It affects an estimated 10% to 15% of the global population[2]and carries a significant disease burden in terms of decreased productivity, increased healthcare costs and reduced health-related quality of life[3].

Despite the global prevalence of IBS, its pathophysiology remains unclear. Studies have reported disturbances in gut microbiota and persistent, subclinical systemic and mucosal inflammation in individuals with IBS[4]. Significant overlaps also exist between patients with IBS and those with dyspepsia[5], hinting at a possible pathogenic role ofHelicobacter pylori(H. pylori) in IBS.H. pyloriis a prevalent gramnegative bacterium that grows in the gut of more than half of the world’s population,and it is even more common in developing countries[6]. The mode of transmission ofH. pyloriis unclear, but believed to be fecal-oral.H. pylori, especially strains that produce cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) protein, causes chronic inflammation in the stomach and duodenum, microbial dysbiosis[7]as well as elevated systemic inflammation[8].H. pyloriinfection has been linked to several conditions, including dyspepsia and even hyperemesis gravidarum[9].

However, its role in the pathogenesis of IBS remains largely unknown. Some studies have highlighted increased rates ofH. pyloriinfection in patients with IBS compared to healthy controls[10,11], while others have disputed this and found no association betweenH. pyloriinfection and IBS[12]. This association has been challenged asH. pyloriis thought to affect mainly the upper GI trait instead of the lower GI tract.Some also contend that the association is merely fortuitous given the widespread prevalence ofH. pyloriinfection globally[6]. This meta-analysis thus aimed to investigate and better clarify the role ofH. pyloriin the pathogenesis of IBS. A better understanding of the pathogenesis of IBS has important clinical implications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search was performed in accordance with Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. By using the keywords “H. pyloriORHelicobacterORHelicobacter pyloriOR infection” AND ”irritable bowel syndrome OR IBS”, a preliminary search of PubMed, Medline, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Science, Google Scholar and WanFang databases yielded 2924 papers published in English between 1 January 1960 and 1 June 2018. Attempts were made to search grey literature as well, using Google search engine and the Open System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe database. Title/abstract screening were performed independently by three researchers (Q.X.N., N.X.F. and W.R.L.) to identify articles of interest. For relevant abstracts, full articles were obtained, reviewed and also checked for references of interest. If necessary, the authors of the articles were contacted to provide additional data.

Full articles were obtained for all selected abstracts and reviewed by four researchers (Q.X.N., N.X.F, W.R.L. and Y.Q.K.) for inclusion. The inclusion criteria for this review were: (1) Published case-control or cross-sectional study; (2) patients with IBS; and (3) confirmed/laboratory testing for presence ofH. pyloriinfection. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus amongst the three researchers. Each study was carefully reviewed and the primary outcome measure of interest was the proportion ofH. pyloriinfection in patients with IBS compared to a control group. Odds ratio (OR) were calculated for each individual study, and estimates were pooled and where appropriate, 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) and P-values were calculated.

Heterogeneity amongst the different studies pooled was examined using theI2statistic and Cochran’sQtest. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot and Egger test. All analyses were performed using MedCalc Statistical Software version 14.8.1 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; http://www.medcalc.org; 2014)and STATA version 13.0 (2000; STATA Corp., College Station, TX, United States).

RESULTS

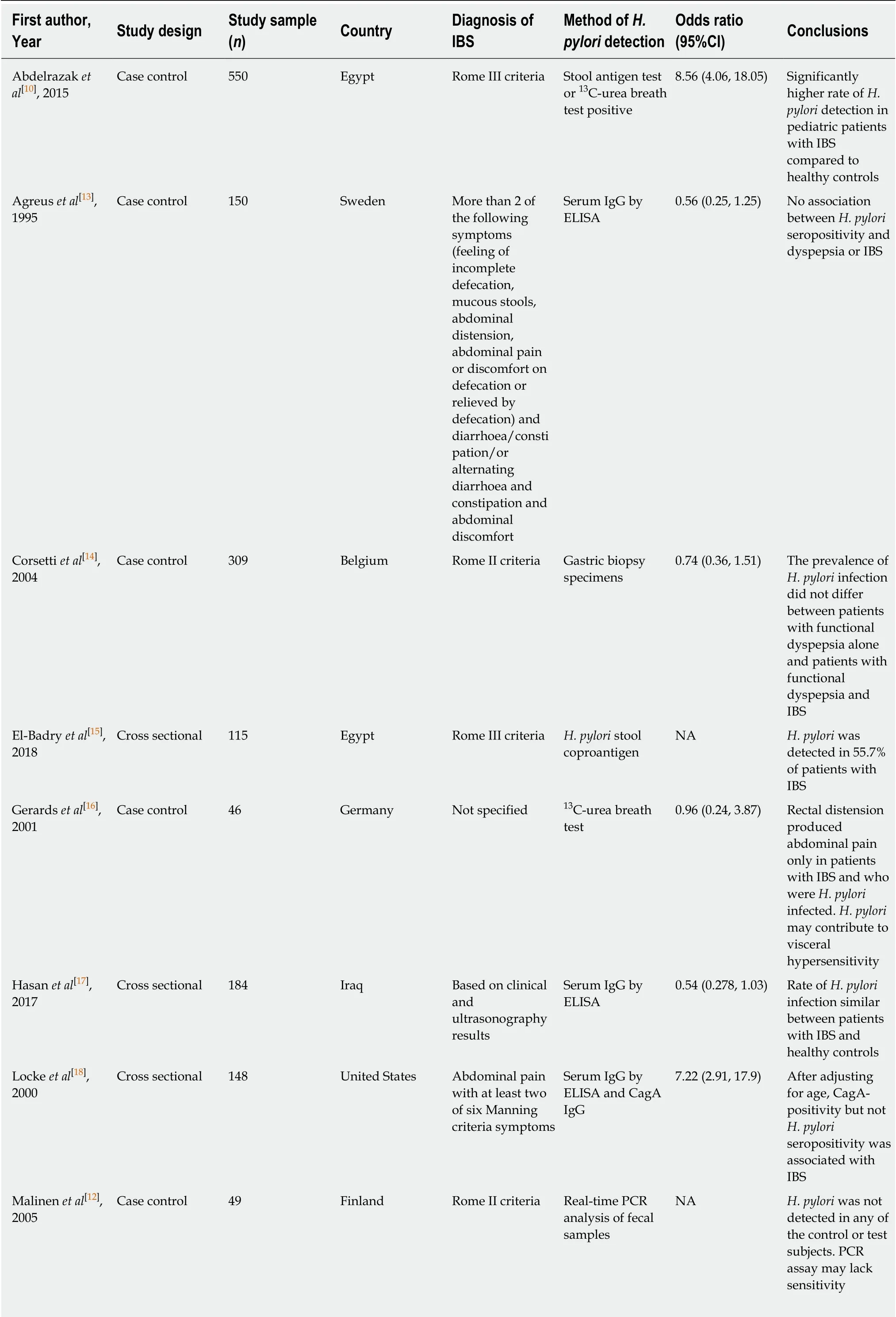

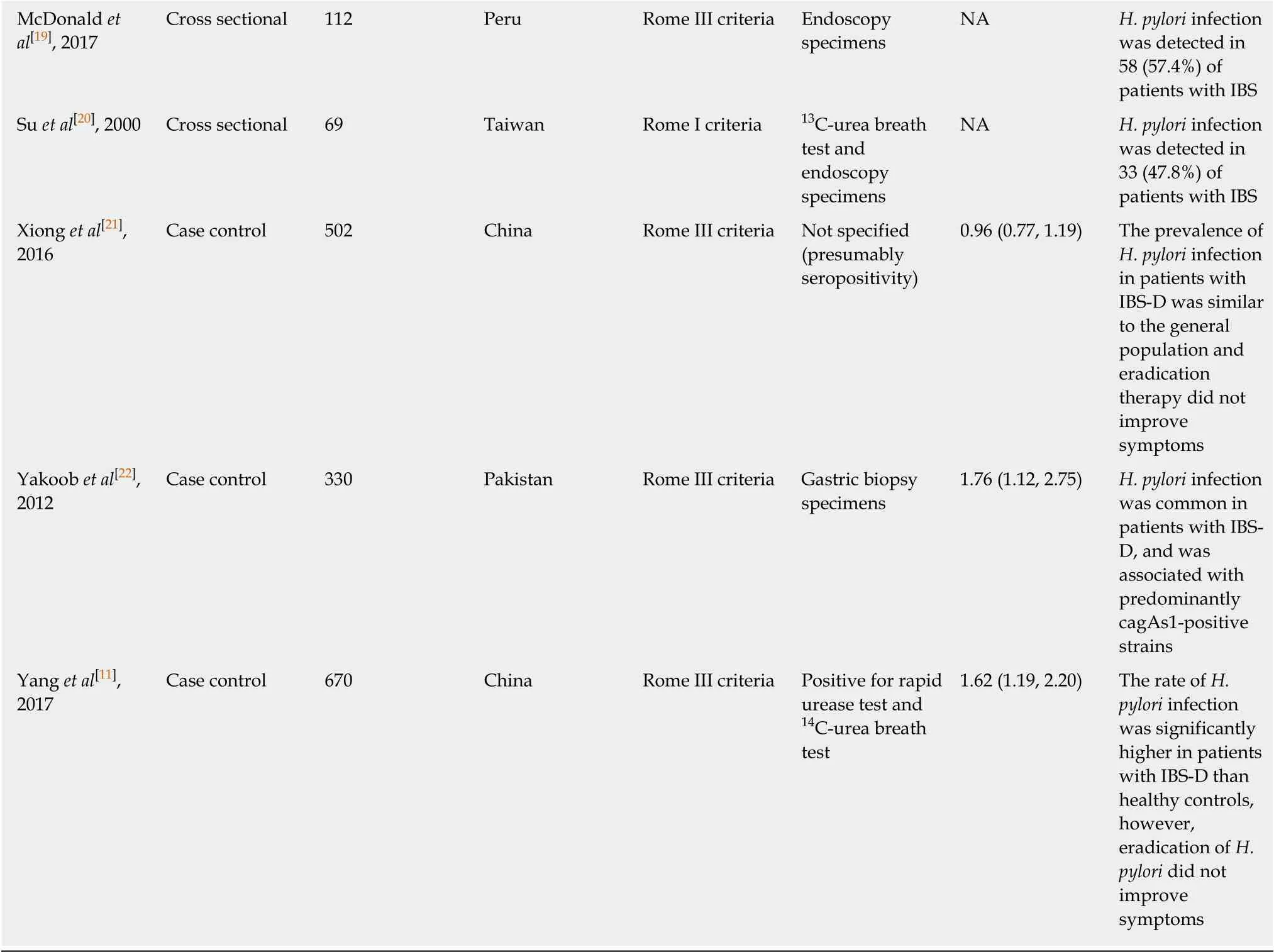

The literature search and abstraction process (and reasons for exclusion) was detailed in Figure 1. The key details of each study were extracted and summarized in Table 1[10-22]. A total of 13 studies were systematically reviewed. Four studies were excluded from the final meta-analysis as three did not have a control group while one did not detectH. pyloriinfection in either patients with IBS or healthy controls, hence no OR could be calculated.

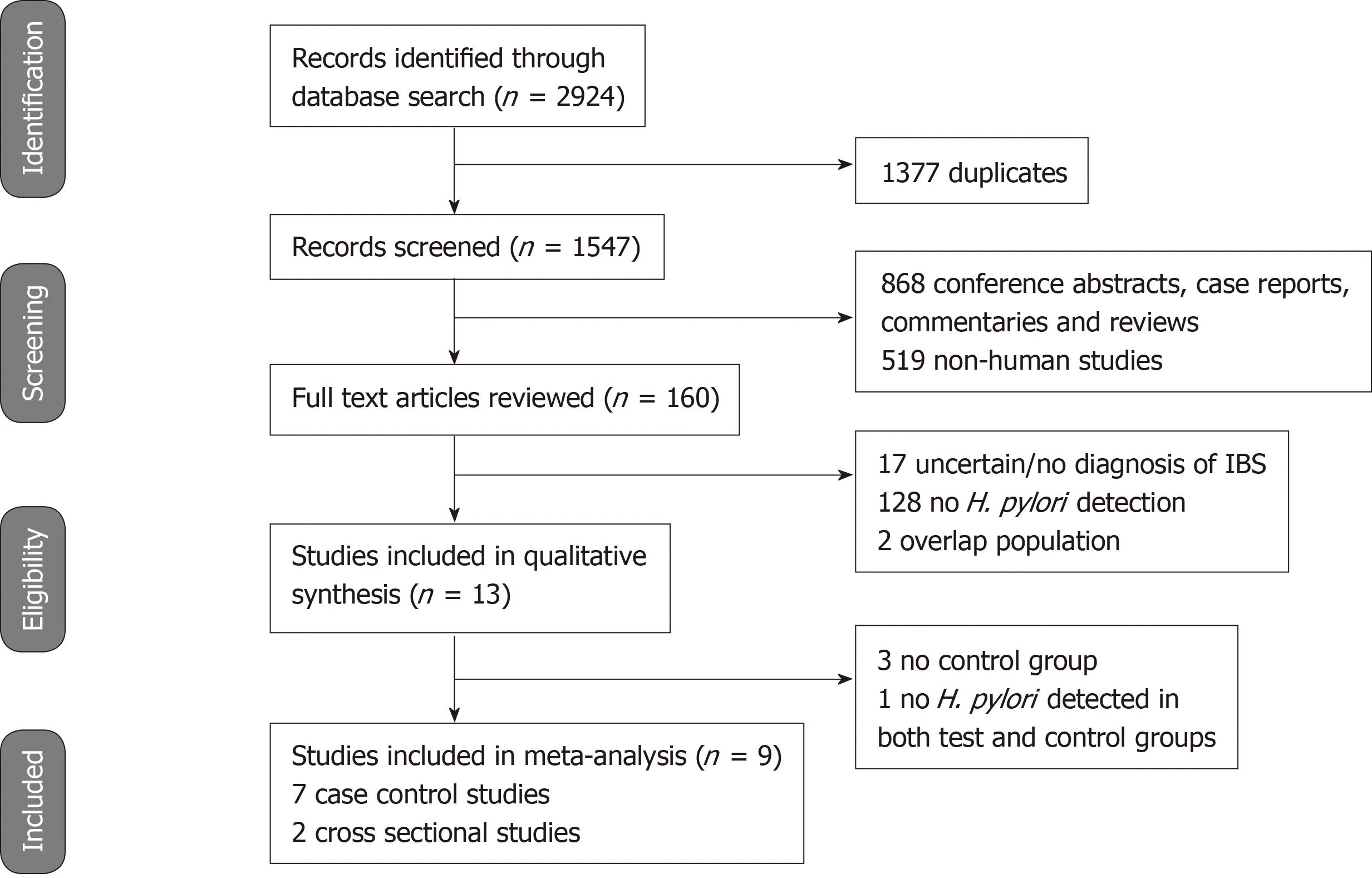

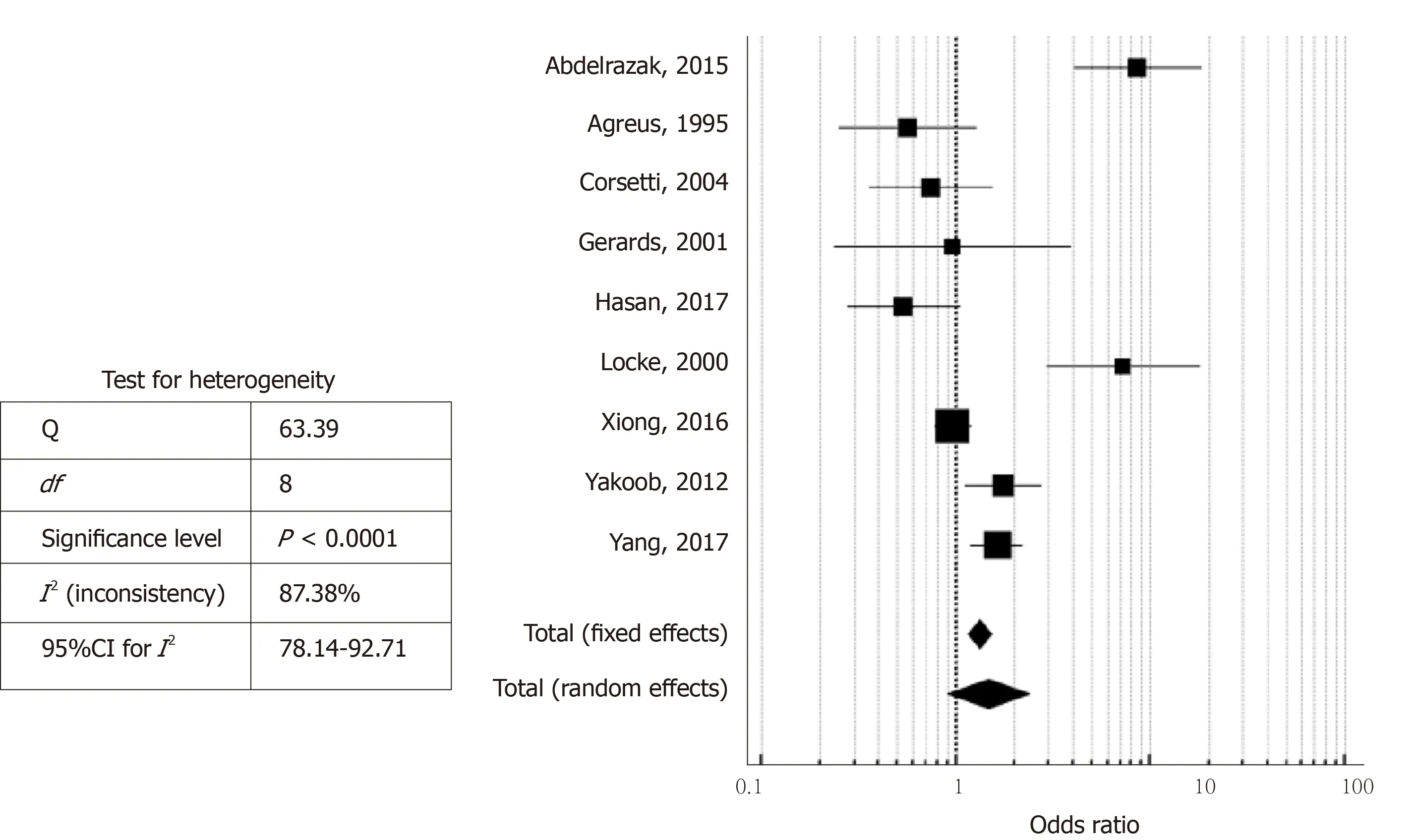

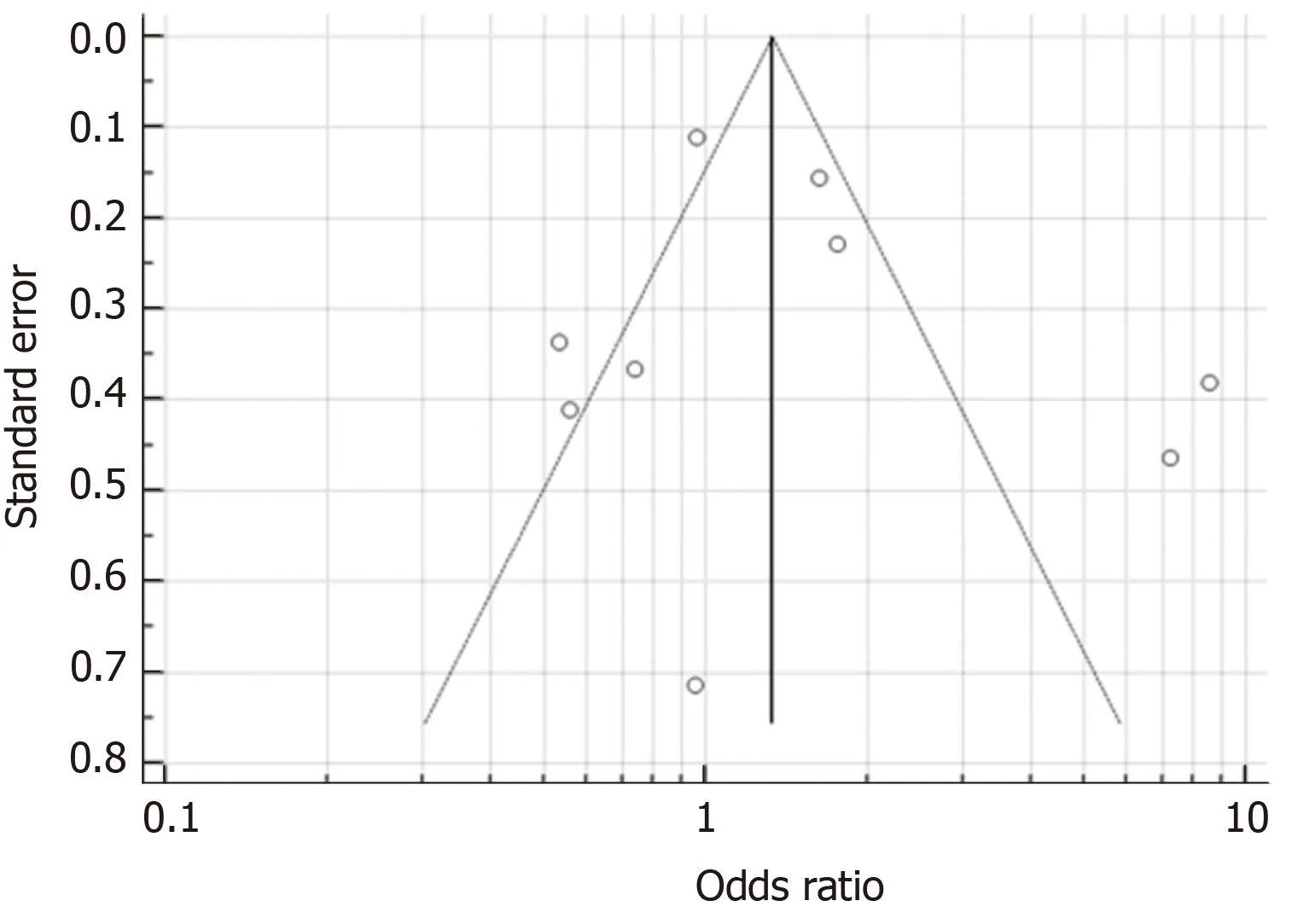

As seen in Figure 2, the studies had an overall high degree of heterogeneity (I2=87.38%), likely due to the different study designs and method of detection ofH. pyloriemployed. Random-effects meta-analysis found that patients with IBS did not have a significantly increased likelihood ofH. pyloriinfection, as the pooled OR was 1.47(95%CI: 0.90-2.40,P= 0.123). Separate subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses were likely underpowered and hence, were not conducted due to the small number of studies available. With regard to the possibility of publication bias, visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed a roughly symmetrical distribution of studies (Figure 3)and encouragingly, Egger test was not significant for publication bias (P= 0.189).

DISCUSSION

Overall, current evidence suggests that patients with IBS may have an increased likelihood ofH. pyloriinfection, but this is not statistically significant (pooled OR 1.47,95%CI: 0.90-2.40,P= 0.123). It must also be acknowledged that all of the available studies reported only crude odd ratios and did not adjust for potential confounders,further weakening any potential association between IBS andH. pyloriinfection. To the best of our knowledge, this review is the first to examine the association between IBS andH. pyloriinfection. The current meta-analysis is therefore a novel and significant contribution to current literature.

It is well demonstrated thatH. pyloriinfection leads to chronic inflammation and is involved in the etiopathogenesis of atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia and pepticulcers[23]. Patients with IBS have been found to have increased lamina propria immune cells in the colonic mucosa[24]and significantly reduced levels of oleoylethanolamide(a fatty acid amide with anti-inflammatory properties) when compared to healthy controls[25]. These are suggestive of chronic, subclinical inflammation at the microscopic level[26]. Increased infiltration of mucosal mast cells have also been reported in the GI tract of patients with IBS when compared to healthy controls[27]. In considering the possible pathogenic mechanisms of H. pylori in relation to IBS, H.pylori infection has been associated with elevated inflammatory markers[8], increased mast cell activation[28]and gastric mucosal and neural remodeling[29]. Vacuolating cytotoxin A[30]and the neutrophil-activating protein[28]of H. pylori are both potent mast cell stimulators. Although a definite and consistent pattern of immune dysregulation has yet to be established in patients with IBS, increased mast cell activation and immune activity in the gut may correlate with symptoms of visceral hypersensitivity[31].

Table 1 Characteristics of all studies included in this meta-analysis (arranged alphabetically by first author’s last name)

H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; CagA: Cytotoxin-associated gene A; ELISA: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-D:Irritable bowel syndrome associated with diarrhea; NA: Not available.

Furthermore, in a study utilizing the rectal barostat to elicit abdominal symptoms in patients with IBS, positive results were seen almost exclusively in H. pylori-positive patients with IBS, suggesting a potential role of H. pylori in stimulating visceral hypersensitivity[16]. Preclinical and clinical studies have often reported a link between increased intestinal mucosal inflammation and changes in sensory-motor function[32,33].As such, H. pylori infection may result in gastric dysmotility and neuroplastic changes in the afferent neural pathways, giving rise to visceral hypersensitivity and prototypical IBS symptoms.

On the other hand, contrary findings have also been reported. A study on patients with functional dyspepsia found no association between H. pylori infection and increased pain perception of gastric distension[34]. Studies that investigated the effect of H. pylori eradication therapy on IBS symptoms also found no significant differences at follow-up[11,21]. However, the relationship is difficult to analyse as it may be confounded by the fact that H. pylori is eradicated with antibiotics, which is also associated with a significantly increased risk of developing IBS[35]and may also aggravate IBS symptoms[36].

Figure 1 Meta-analysis of observational studies flowchart showing the studies identified during the literature search and abstraction process.

A fundamental understanding of the pathogenesis of IBS is still lacking.Additionally, psychological factors such as stress, depression and anxiety are known to contribute to the pathogenesis[37]. Our study investigated another potential contributory factor. Patients with IBS may have an increased likelihood of H. pylori infection albeit this is not statistically significant. The role of H. pylori eradication therapy is also unclear as it does not appear to improve IBS symptoms in the limited studies available.

Other limitations of current evidence that must be discussed include the fact that some of the available studies[13,18]used a self-report symptom questionnaire in the diagnosis of IBS. There is a known wide variability in the definition of constipation and diarrhoea[38], and the subjectivity and inter-study variability in the diagnosis of IBS could further affect the reliability of current findings. Also, some of the studies[13,18]included in the meta-analysis did not investigate study participants for organic disease that may contribute to IBS-like symptoms. Limited studies also performed CagA testing. In one study[18], CagA antibody positivity but not H. pylori seropositivity was found to be significantly associated with IBS. Future studies should examine the effect of CagA positivity as the CagA toxin is an important H. pylori virulence factor associated with a greater inflammatory response[39]. There was also a significant degree of heterogeneity amongst the various studies included in the meta-analysis (I2= 87.38%). This could stem from the subjectivity and different definitions used in the diagnosis of IBS as previously discussed, as well as the differing tests used to detect H. pylori infection, e.g., serum IgG antibodies, urea breath test and stool antigen assay.Moreover, the commonly-used serologic test is unable to distinguish between current and previous H. pylori infection as it remains positive for years, even after H. pylori eradication therapy[40]. Although some studies carefully selected only individuals who have no history of previous H. pylori eradication therapy[16], it was less clear in other studies. The duration of H. pylori infection may also affect our analysis as study subjects with more longstanding infection may have greater mucosal inflammation and more significant GI symptoms.

Last but not least, the influence of H. pylori on the composition of distal gut microbiota is an important area that deserves further study. Microbial dysbiosis is a known hallmark of IBS[41]. However, it is unclear how H. pylori, which is thought to affect mainly the upper GI tract, may affect the lower GI tract[42].

In conclusion, current evidence does not support an association between IBS and H.pylori infection. Patients with IBS may have a slight increased likelihood of H. pylori infection albeit this is not statistically significant. This relationship is complicated by admittedly problematic study designs and potential confounding factors. The role of H. pylori eradication therapy also remains unclear as it does not appear to improve IBS symptoms. Further rigorous and detailed studies with larger sample sizes, carefully selected subjects, and after H. pylori eradication therapy are warranted. The influence of H. pylori on gut microbiota should also be investigated.

Figure 2 Forest plot showing the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of studies on the likelihood of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.

Figure 3 Funnel plot (with pseudo 95% confidence intervals) to assess publication bias.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research results

A total of 13 clinical studies were systematically reviewed and nine studies were included in the final meta-analysis. Random-effects meta-analysis found a slight increased likelihood of H. pylori infection in patients with IBS, albeit this was not statistically significant (pooled odds ratio 1.47,95% confidence interval: 0.90-2.40, P = 0.123). H. pylori eradication therapy also does not appear to improve IBS symptoms in the limited studies available.

Research conclusions

Current evidence does not support an association between IBS and H. pylori infection. This relationship is complicated by admittedly problematic study designs and potential confounding factors. H. pylori is eradicated with antibiotics, which is also associated with a significantly increased risk of developing IBS and may also aggravate IBS symptoms.

Research perspectives

Further rigorous and detailed trials with larger sample sizes, carefully selected subjects, and after H. pylori eradication therapy are warranted. The influence of H. pylori on gut microbiota also remains unknown and should be investigated.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年37期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年37期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Is total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy superior to open procedure? A meta-analysis

- Long-term outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma that underwent chemoembolization for bridging or downstaging

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Beyond the natural history

- Soluble mannose receptor as a predictor of prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure

- Estimating survival benefit of adjuvant therapy based on a Bayesian network prediction model in curatively resected advanced gallbladder adenocarcinoma

- Short-term efficacy of robotic and laparoscopic spleen-preserving splenic hilar lymphadenectomy via Huang's three-step maneuver for advanced upper gastric cancer: Results from a propensity score-matched study