tuning up

by Hatty LIU

Noise. Unpredictability. Rebellious lyrics chanted by crowds of thousands. Outdoor music festivals may seem like everything China’s “harmonious society” would want to weed out, but have flourished in the hundreds across its cities and hinterlands in the last decade, often supported by local authorities who see economic benefit to unleashing youthful exuberance in a controlled and consumerist setting. Between the pressures of state and society, organizers, veterans, first-time attendees, and musicians sound off on how China’s festivals can continue to survive in a complex environment, and preserve their authentic voice.

內地的第一个音乐节诞生在2000年,

被看作是音乐的乌托邦;

如今,随着越来越多的中小城市争相举办,

音乐节也成了资本的竞技场

T

o the surprise of few old fans, and delight of many new ones, “Sex, Drugs, Internet” struck manic chords at music festivals across China this fall, even if just in song.

Released in a 2011 album of the same name, this Ian Drury tribute by synth-rock/punk band New Pants parodied the spiritual emptiness of today’s youth. But this year's festival audiences had been trading semi-satiric mutterings that the recent winners of iQiyi’s campy web reality show , who have lately shot ads for corporations like JD.com, might have bowdlerized their own provocative song title to something more like “Beauty Queens, Cough Medicine, E-Mail.”

To many who’ve followed the mass popularity of the iQiyi show with trepidation, the chance to hear the lyrics unmolested was why they spend hours traveling to the increasingly remote locations of Chinese festivals in the first place—often braving unruly crowds, traffic, and even typhoons to do so. “I think the future of the entire rock scene, and of music and bands, is in live performance,” a 30-year-old programmer from Shanghai, surnamed Shao, declares from the audience at September's East Sea Music Festival in Zhoushan, Zhejiang province.

Introducing himself as a “long-time supporter of Chinese rock,” Shao views outdoor festivals as the last outpost of rock ’n’ roll rebellion in a rising tide of conformity and commercialism. “At this stage we still have some space to exist, a process of resistance.”

It’s a message that seemed especially apt among East Sea’s closing night crowd, most of whom would have been in primary school when New Pants released their controversial hit, but shouted along regardless to the word-salad lyrics that were reportedly cut from New Pants’ first episode: “Let’s go wild/…Never go outside!”

But while China’s music festivals appear to be more popular and numerous than ever, promoters, founders, and fans have expressed concerns that the festivals’ original freewheeling spirit is at risk of being permanently diluted by an array of imitators, overzealous regulators, jumpy officials, and greedy organizers.

Today’s festivals, “are more of a lifestyle choice. In terms of the actual sound, the artistry, there are better options,” admits fans like Shao, who says he usually looks for quality music and innovative bands in livehouses, bars, or simply on apps like Spotify. In China, as elsewhere, consumerism has transformed formerly countercultural festivals into mainstream entertainment, often held during public holidays such as Labor Day in May or October’s National Day “golden week,” and timed to give early spring previews or late-autumn last hurrahs to the tourist season in lower-tier cities and scenic areas.

The free kegs at Chinese festivals in the legendary early 2000s are gone, replaced by swanky beverage tents sponsored by global brands like Bacardi or Monster Energy Drink, though are otherwise substance-free (New Pants’ lyrics remained the most debauched moment of the entire East Sea weekend). Ticket prices have also risen, to around 900 RMB for a typical three-day pass—20 percent of the average graduate monthly salary.

“It’s now more a consumption habit, not a listening one,” says Shao. “If I don’t shed tears, then at least I can shed some sweat.”

L

ike most cultural imports in China’s post-reform era, it’s easy to pinpoint the exact sweat-soaked, denim-clad moment that festivals first plugged themselves into the mainland’s music scene. While there had been multi-band music events in the 1990s, the first to use the term “festival” (節), and emphasize such a rowdy atmosphere, was a two-day student and alumni recital held in the auditorium of Beijing’s Midi School of Music over 2000’s Labor Day holiday. With free entry, free beer, and advertising mostly by word-of-mouth to 1,000 or so attendees, it was “special,” according to Midi principal Zhang Fan.

“There was a construction site on the other side of the [school’s] red-brick wall, so a number of shirtless migrant workers mounted ladders to watch,” wrote Zhang in an undated and frequently quoted reminiscence called the “True Records of the First Midi Music Festival.” “I said, ‘Come on in, brothers,’ and they all came. Music is like that—free, without hierarchy, unconcerned with whether you’re rich and poor. It’s the most direct and unpretentious thing.”

But even at that relatively utopian beginning, changes were starting to appear. In October 2000, five months after the Midi Festival, the Chinese government’s Tenth Five-Year Plan included the term “cultural industry” for the first time. Whereas rock and popular musicians had once existed defiantly outside (if still quietly) the state-run ecosystem of “culture”—consisting of artists and troupes attached to the military and state instituions, and performance opportunities on state television—the new term recognized their work as an “industry,” on par with service or manufacturing, which the state may choose to support for tangible political or economic gains.

While China had just six music festivals annually in 2008, most of them held in Beijing, their prevalence has grown exponentially in their second decade: multiplying to 60 in 2010, 148 by 2014, and over 260 today. City and county governments, particularly those in less developed regions, have been instrumental to this expansion, providing permits, venues, and financial support to these largely unprofitable ventures (80 percent of Chinese music festivals are losing money, reports think tank China Music Business).

The trend in local festivals was, aptly, also started by Midi in 2009, when the organizers accepted an invitation from the cultural department of the minor (by Chinese standards) city of Zhenjiang, Jiangsu province, to hold a festival on a local island. “The department chief was quite frank, ‘We’re inviting you because we want to borrow Midi’s influence to improve the image of our city, and let youths from across the country bring their culture and enthusiasm here,’” Zhang told Sina Entertainment that year.

In return, the Zhenjiang government covered most of Midi’s operational costs, and saw occupancy rate of area hotels shoot to 91 percent as nearly 80,000 attendees descended on the industrial city for the three-day festival weekend. This form of collaboration can now be found across the country: 50 percent of the festival market now belongs to second and third-tier cities and below. Scenic areas, resorts, property developers, marketing agencies, and even e-commerce giants like Alibaba—which live streams a “virtual music festival” during its November 11 sales event—are also beginning to organize them.

According to China Music Business, however, 50 percent of the 263 festivals held in China last year were first-time events, and 60 percent of them may not survive to play again this year. Zheng Yun, East Sea’s founder and a native of Zhoushan, recalls initial difficulty introducing the concept to a fourth-tier island city largely known for shipbuilding, fishing, and exporting its under-40 population to nearby metropolises like Shanghai and Hangzhou.

“I remember clearly that it rained in our first year, and only about 500 people came, mostly fishermen from the nearby villages,” Zheng tells TWOC. “The genre we chose was jazz, so all these local families were standing around, wondering why there were no lyrics.”

Better marketing and a shift toward indie bands of other genres, such as rock festival regular Escape Plan, drew 3,000 to 4,000 attendees in Zheng’s second year, and the sudden enthusiastic support of the government. “The mayor has come to our events and told us, ‘There are so many young people here. Zhoushan lacks young people and young energy,’” Zheng says, explaining that it is more than just the chance to draw tourists, or meet cultural and service-industry targets, that has led typically risk-averse officials to embrace events that seem to maximize noise, unruliness, and unpredictability—it is the envious achievement of bringing “youth culture” and a cosmopolitan cachet to an aging hinterland.

Midi and the Strawberry Festival, started by Modern Sky Record in the Beijing suburbs in 2009, have become the two largest and most influential festivals on the mainland. Modern Sky now holds 20 events annually across China, and the two festivals tour in locations as diverse as the Beihu Wetlands in Changchun, Jilin province, and the Tenglong Karst Caves in Enshi, Hubei province.

Not all such joint ventures are so successful—inexperienced organizers and local politics often lead to poor crowd control, corruption, or simply an under-estimation of the manpower and budget required to host tens of thousands of exuberant visitors at a remote location.

This July, the Beijing-based company that formerly organized the Zhangbei Grassland Music Festival branded the 2019 edition a “fake festival,” alleging that the Zhangbei government had broken a 10-year contract with them in order to hand the organizing rights (and share of the profits) to a local partner. The new organizers inexperience, along with lack of police and traffic support from the government, created a three-day fiasco with no trash pick-up, near-stampedes at the ticket gate, and 15-hour gridlocks outside the venue.

In 2017, there was a similar brouhaha after pop star Nicki Minaj accused a Shanghai festival of violating the trademark of a better-known Indonesian event, and cancelled her appearance. Midi’s Tenglong Caves outing in 2016, on the other hand, drew concerns from environmentalists and was widely mocked by longtime fans, who pointed out that local officials had also livestreamed a bikini pageant at the same location the same month in a tacky bid for attention.

“The way I see it, small festivals have two possibilities behind them: Either the government wants to meet some industry targets, or somebody is laundering money,” says East Sea flea market vendor Zhang Jing, who has been attending festivals for over a decade. “It shouldn’t be just a system of ‘milk the tourist once, then disappear the next year.’”

He is a rare veteran who has followed the industry across both decades—Strawberry Festival organizers had estimated this year that around 90 percent of their attendees are between the age of 18 and 20—but Zhang is no longer idealistic about them. “At Midi, it’s still the same bunch of noisy kids after all these years…but what’s the point?” he sighs. “When I come here now, it’s purely to enjoy myself. My heart is still in that other era.”

I

t was like a Chinese Woodstock; people seemed, at least, to be free and energetic,” an anonymous attendee wrote in 2015 of the inaugural Midi Festival for music blog Jammy FM.

There’s still plenty to enjoy at Chinese festivals, where, outwardly, little has changed in the exploratory atmosphere despite increased official involvement. Midi remains iconic for its mosh pits, mud fights, and even a flag-burning (with a Japanese flag), while East Sea almost resembles an indie cliché due to all the non-mainstream hobbies it attracts: the skateboarder that zooms past rows of vintage and handicraft vendors; creative anachronists prowling in full costume; a DJ stage that accommodates lesser known musical genres, like ska, before a body-surfing crowd.

Permission to build bonfires, light fireworks, and camp has been wrested from the authorities, and there is an open-mic stage in the campground, where attendees and volunteers can show off their talents after hours. The staff at one tattoo stand, first-timers at the festival, tells TWOC elatedly that they made 3,000 sales in one night, normally a month’s business.

These scenes, though, are choreographed chaos: The tattoos are stick-on and henna, and, like the dreadlocks being attached to long lines of youths next door, are removable before the wearers return to work or college on Monday. East Sea organizers say that the vendors, skateboards, and even inflatable chairs are assigned to designated areas; the youths lolling on the beach must clear their picnic blankets and tents by the end of the last act of the night. A helicopter flies past at intervals, above an ambulance and armored police van standing by. “What you see at music festivals is a stage, and behind it, a lot of policy power and guarantees,” says founder Zheng.

The past decade’s explosion in government-run festivals in China has paradoxically taken place alongside tightening restrictions on both music distribution and public life. In the run-up to the 70th anniversary celebrations of the PRC’s founding this year, the festival market disappeared in the capital city altogether, and has shrunk elsewhere.

Modern Sky founder Shen Liming has told several media outlets that the Strawberry Festival has trouble obtaining permits to host events with more than 100,000 attendees, thus limiting both its reach and profitability. At smaller festivals, anti-corruption measures have also curtailed state budgets to invite big-name pop stars.

East Sea organizers confirm these challenges. “We don’t apply for the permits for foreign artists, because we might get denied,” executive director Yun Biao states baldly. Foreign artists’ political beliefs, moral conduct, social media activity, and lyrics are all scrutinized by the Ministry of Culture before they’re issued a permit to perform in China, with little transparency in the procedure. A new 20-percent tax issued on ticket sales for foreign acts in February has also deterred international artists from performing on the mainland.

Chinese artists must typically submit their own set-lists, lyrics, and audio-visual stage effects for pre-approval by the local cultural department, and may even face interference during the show itself. At the 2014 Midi Festival, Queen Sea Big Shark drummer Tong Yan infamously brawled with a stage manager who pulled the plug when the band were halfway through their set—apparently, the show was about to overrun the strictly allotted time that had been granted by Beijing’s authorities, which could lead to fines.

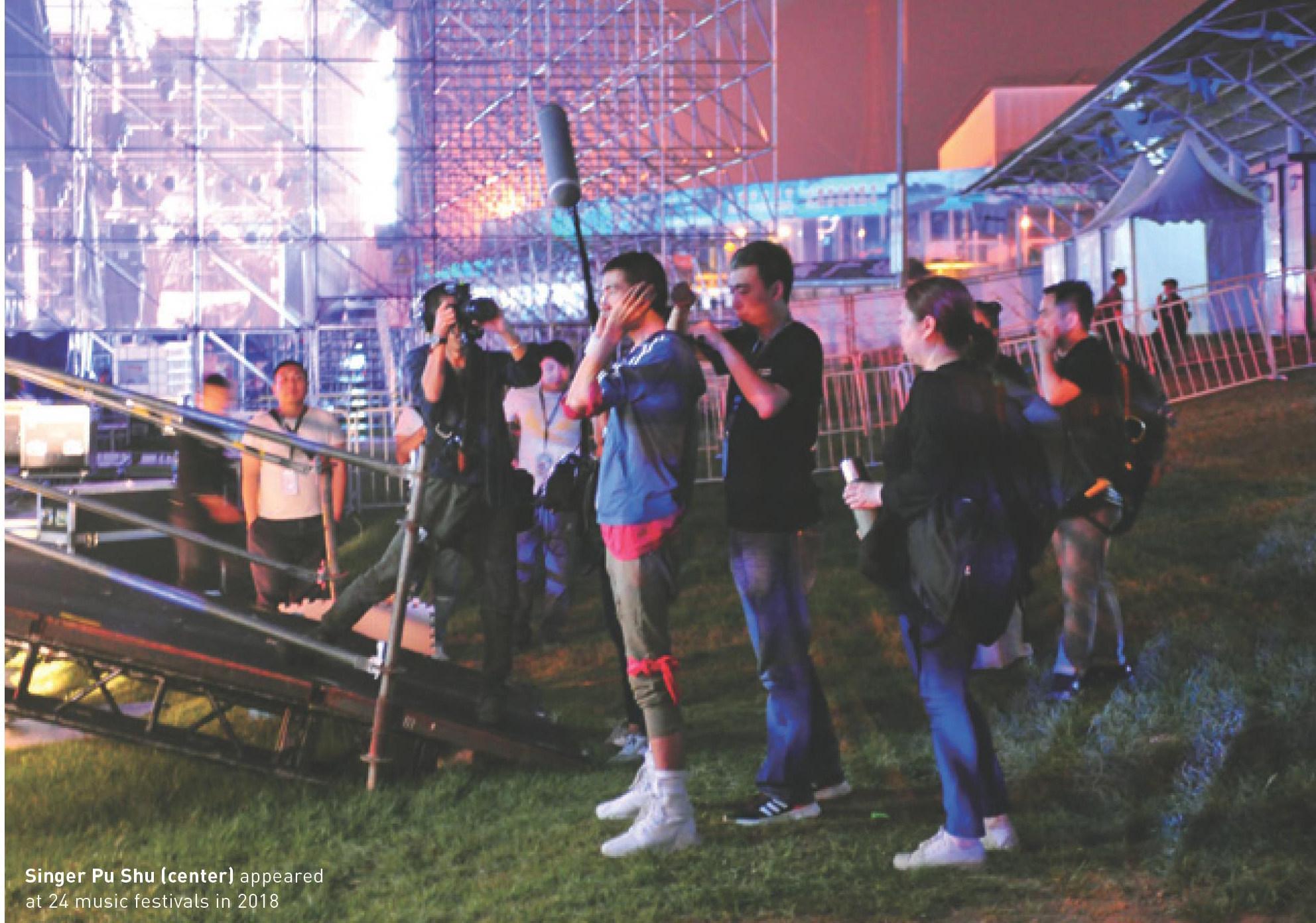

The explosion of events, coupled with a shrinking pool of acceptable talent, has also created a homogenized sound. Indie folk duo Landlord’s Cat played at 31 festivals in 2018, according to China Music Business, and during the first half of 2019 alone, 27 bands had already appeared at five or more. As folk-rock singer Li Zhi observed on Weibo in 2014, “What China has is not a lot of festivals, but a lot of bands who keep singing the same few songs, not even changing the arrangement, and saying the same lines and keeping the same look onstage.”

East Sea founder Zheng believes that the success of his nine-year-old festival can be seen simply in the fact of having become professional and memorable enough to be left mostly alone. “Now, when we announce the dates for the festival, all the hotels and bed-and-breakfasts near us get booked up, and of course the mayor can see this, so they let us to do things our way, instead of their way.”

“We’re the only festival in China that has been in the same location and under the same general leadership since it was founded,” he notes proudly. Tickets, too, have stayed relatively low-cost—just over 300 RMB for the whole weekend. “We’ve managed to maintain our ideals.”

Midi’s Zhang Fan, however, put the situation more cynically back in 2009, when asked by Sina whether he felt “used” by Zhenjiang’s government. “All art and culture in China are being used,” he replied. “We just keep doing what we love, and whoever wants to use can use.”

W

e’re past the playful era, the noisy era,” mourns Zhang Jing. Not all attendees, though, believe it’s only policy that is to blame. “I teach at a music shop, and parents keep asking me, can you take exams in this?” scoffs a college-age amateur rocker at East Sea, who introduces himself as Dashan. “I always want to reply, what’s the point of exams in electric guitar? They want to turn it into something industrial.”

IQiyi’s polarizing reality show—nine out of whose 31 bands also appeared at East Sea this year—initially seemed to have confirmed these fears this summer, with pastel-colored posters showing rockers smiling above the logo of the sponsoring yogurt company.

Subsequent episodes, lamented a review on blogging platform Jianshu, resembled “[talk show] with a performance inserted”: just 25 minutes of singing, and the rest of two hours devoted to voting, lessons in rock and punk history, and interviews where musicians shared mostly personal and financial challenges to their career, keeping well away from collective struggles.

“Rock music does need more attention, but reality shows cause it to fundamentally change, as something that’s used to make money, instead of something that lets you feel rebellious, powerful, alive,” Dashan declares.

Yet as surpasses even to become the summer’s most discussed show on WeChat—allegedly causing a nearly 50 percent increase in rock instrument sales in Beijing music stores, and expanding New Pants’ Weibo following from 100,000 to 1 million—even Dashan can’t suppress his jubilation about the growing audience of his hobby. “When I’m 30, that stage is mine!” he shouts as Shanghai band Theory of Convergence wraps up their set. “That’s what I’m here for,” he tells TWOC. “The experience of meeting people who are like me.”

Founder Zheng doesn’t feel that the evolution from “special performances for rocker youths” as Sina described music festivals in 2009, to “entertainment for all,” is regrettable. “In terms of musical styles, we have a little bit of everything,” he says, “not one thing for one type of person. I feel like the world should be tolerant, that youths should also be tolerant.”

Shao, on the other hand, feels that uncertainties and contradictory attitudes in today’s festival culture are actually assets. “The way I see it, in this immature, conflicted policy environment, Chinese bands at least now have personal freedom. Collectively…well, nothing you can do about that,” he says. “It’s a stolen pleasure,” agrees Zhang Jing.

Rather remarkably, Midi’s Zhang Fan predicted this feeling a decade ago. When his festival first began to tour, he described its growth to Sina as “a victory of ordinary people’s opportunism, to survive between the narrow cracks.”

“To establish something in an unpredictable society like China, it’s necessary to find cracks within stiff regulations and grab hold of opportunities, and win small gains,” he said. Like the new generation of teens thronging the stage for their first glimpse at punk bands they’ve only heard on a reality show, you find something you like, squeeze yourself into the current, and hold on.

汉语世界(The World of Chinese)2019年6期

汉语世界(The World of Chinese)2019年6期

- 汉语世界(The World of Chinese)的其它文章

- MY Country,My Cinema

- Sweet Nothings

- 摇

- You’ve got questions? she’s got answers

- 光影

- Rescue Fees