Breast cancer metastasis to the stomach

Francesco D'Angelo, Alessia Rampini, Silvia Cardella, Laura Antolino, Giuseppe Nigri, Stefano Valabrega, Paolo Aurello, Giovanni Ramacciato

U.O.C. of General Surgery, "Sapienza" Università di Roma, Sant'Andrea University Hospital, Rome 00189, Italy.

Abstract Aim: This study focuses on the stomach as an unusual but not rare site of metastasis of breast cancer.Methods: We performed a literature search on gastric metastasis from breast cancer searching for reviews from 2000 to 2018 and case reports from 2013 to 2018. We found 11 reviews and 36 case reports and we compared their findings about important aspects of gastric metastasis, such as disease free survival, overall survival, symptoms,endoscopic findings, therapy, histology, and immunohistochemistry.Results: The incidence of stomach as site of metastasis of breast cancer ranges from 5% to 18%. Reviews and case reports reached similar conclusions about several of the aforementioned aspects: invasive lobular breast cancer (ILC) is mainly responsible for gastric metastases; disease free survival can vary greatly ranging from 0.5 months to 30 years; gastric metastases usually present with non-specific symptoms, even though five patients in case reports were asymptomatic; linitis plastica is the most common endoscopic finding; immunohistochemistry is essential for differentiating primary gastric cancer from metastasis; the preferred treatment is systemic therapy,but surgery is still an option in case of emergency; median overall survival of patients with gastric metastasis from breast cancer is 24 months.Conclusion: Breast metastasis to the stomach should be considered in any patient suspecting gastric neoplasm previously treated for breast carcinoma, especially if the treated carcinoma was ILC.

Keywords: Gastric metastasis, breast cancer, immunohistochemistry, stomach

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor in the female population. Different histologies metastatize to different organs[1]: ductal cancer metastatizes mainly to lungs, bones and liver, while lobular cancer has a tendency to metastatize to the gastrointestinal system[2,3]. Gastric metastases from breast cancer are not common, but the autoptic incidence is not negligible, and varies from 5% to 18%[3,4]. Gastric metastases are metachronous in most cases and even in patients with a known history of breast cancer it may be difficult to correlate the two diseases to a common cause, since the gastric disease often presents only several years after the treatment for the breast tumor[5,6]. This late manifestation of the disease may lead to erroneous diagnosis in clinical practice and a correct identification of the disease becomes possible only after performing surgery, even though this approach is used only in limited cases. With this study we want to compare current clinical practice found in case reports with the results presented in recent reviews.

METHODS

We performed a literature search aimed at finding reviews published from January 1st 2000 to October 31st 2018 about gastric metastasis from breast cancer and case reports on the same argument from January 1st 2013 to October 31st 2018. The results presented in the reviews and in the case reports were compared with the aim of analyzing eventual similarity and differences in the findings discussed therein.

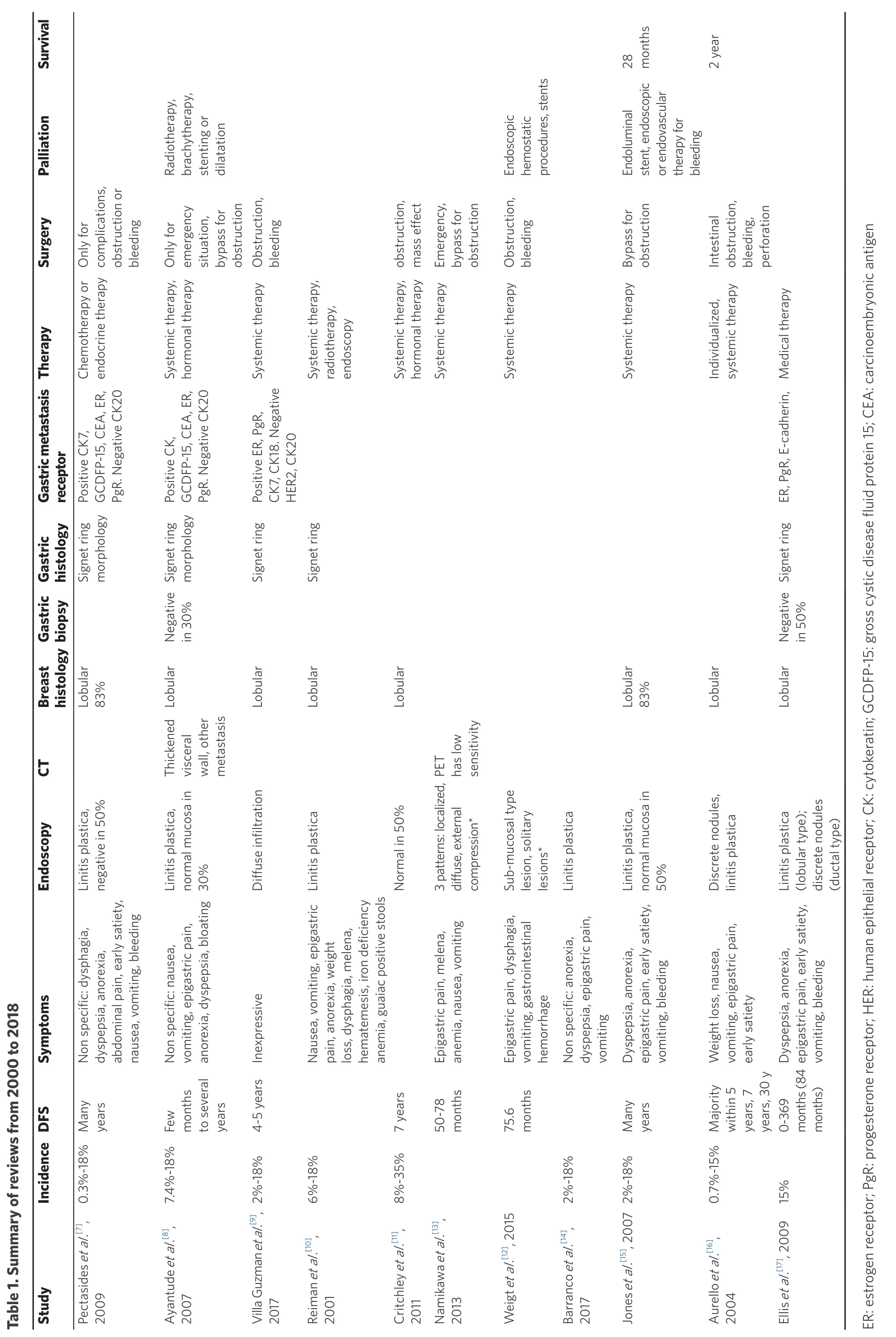

Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1[7-17], whereas characteristic of patients from case reports (2013-2018) are reported in Tables 2-4[9,14,18-51].

RESULTS

Part 1. Reviews

The search for reviews about gastric metastasis from breast cancer was carried out using the combination of words (gastric OR stomach) and (metastasis OR metastases) and (breast) for the PubMed database, using the filter for reviews. Articles written in languages other than English, articles about primary gastric cancer with breast metastasis and about primary breast cancer metastatizing in organs other than the stomach were excluded. The time span considered went from January 1st 2000 to October 31st 2018 and 11 articles fulfilling the criteria were found as a result of the search. The main aspects of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Incidence

Nine of the articles reported the incidence of gastric metastasis from breast cancer: the incidence ranged from 0.3% to 35%, with the value 2%-18% reported in 3 articles.

Breast histology

Nine reviews reached the same conclusion that the most common histological type of breast cancer responsible for gastric metastasis is the lobular cancer. Two of the articles also reported the occurrence of metastasis associated with different types of cancer, with lobular cancer being identified as the cause of metastasis in 83% of the cases.

Disease Free survival

Nine of the reviews cited interval time from the appearance of the primary breast cancer to the presentation of gastric metastasis, however the time intervals were not specifically defined, as for example two articles reported “many years” and one article “few months to several years”. Other articles reported a median disease free survival of 5 years, but gastric metastasis may occur up to 30 years after the primary tumor.

Table 1. Su mm ary of review s from 20 00 to 20 18 Stud y In cide nceD FS Sy mp to ms En do scop y CT B reast histolo gy Ga stric b io p sy G a stric h isto lo g y G astric m etastasis recep to r Th erap y Su rg ery Pa llia tion Su rvival Pectasid es et al.[7],20 09 0.3%-18%Many years Non specific: dysp hagia,dyspdo ep sia, an orexia,ab minal pain, early satiety,nausea, vom iting, b leed ing Linitis p lastica,negative in 5 0%Lo83bu%lar Signet rin g morp hology PoGC sitive C K7,EA DFP-15, C, ER,PgR. N egative CK 20 Ch em otherapy or endo crine therapy On ly fo r comp lications,obstru ctio n or bleeding Ayan07tu de et al.[8],20 7.4%-18%Few months toyears several No n sp ecific: nausea,voan miting, ep igastric pain,orexia, d yspepsia, bloatin g Linitis pal mu lastica,sa in no rm%co 30 Th ickened visceralth wall, o er metastasis Lo bu lar Negative in 30%Signet ring morp hology PoGC sitive C K,, C DFP-15 EA, ER,PgR. Negative CK 20 Systemon ic therapy,ho rm al therapy On ly fo r emsitu ergency ation,bypass forn obstru ctio Radiotherapy,y,brachyth erap sten ting o r dilatation Villa Guzm an et al.[9],20 17 2%-18%4-5 years Inexpressive Diffuse infiltration Lo bu lar Signet ring PoCK sitive ER, PgR,7, C K18. N egative HER2, CK 20 System ic therapy O bstruction,bleeding Reim01an et al.[10],20 6%-18%Nausea, vom itin g, ep igastric pain, an orexia, w eight loss, d ysphagia, m elen a,hematemesis, iron d eficiency an em ia, gu aiac p ositive stools Linitis p lastica Lo bu lar Signet rin g System ic therapy,radiotherapy,endo scop y Critchley et al.[11],20 11 8%-35%7 years Norm al in 5 0%Lo bu lar Systemon ic therapy,ho rm al therapy obstru ctio n,mass effect Namikawa et al.[13],20 13 50-78 months Epan igastric p ain, melena,em ia, n ausea, vo miting 3 patterns: localized,diffuse, external compression*PET has low sensitivity System ic therapy Em ergency,bypass forn obstru ctio Weigt et al.[12], 20 15 75.6 months Epvohemo igastric p ain, dysp hagia,miting, gastro in testinal rrhage Sub-mu cosal type lesion, solitary lesion s*System ic therapy Ob struction,bleeding Endoscopic hemostatic procedures, stents Barran co et al.[14],20 17 2%-18%Non spep ecific: an orexia,ain,dysp sia, epigastric p vo miting Linitis p lastica Jones et al.[15], 20 07 2%-18%Many years Dysp ep sia, an orexia,epvo igastric p ain, early satiety,miting, bleeding Linitis pal mu lastica,sa in no rm%co 50 Lo83bu%lar System ic therapy Bypass fo rn obstru ctio Endolum inal stent, endoscopic or endovascular therapy for bleeding 28mo nths Au rello et al.[16],20 04 0.7%-15%Majo rity5 with in years, 7 years, 30 y Weight loss, n ausea,vo miting, ep igastric pain,early satiety Discrete n od ules,linitis p lastica Lo bu lar Individu alizederapy,system ic th Intestinal obstru ctio n,bleeding,perforatio n 2 year Ellis et al.[17], 20 09 15%0-36 9 months (8 4 months)Dysp ep sia, an orexia,epvo igastric p ain, early satiety,miting, bleeding Linitis p lastica(lob ular typ e);discrete nod ules(d uctal type)Lo bu lar Negative in 50%Signet ring ER, PgR, E-cad herin, M ed ical therapy ER: estro gen recep to r; P gR: p ro gesteron e recep to r; H ER: h um an ep ithelial recep to r; C K: cytokeratin; G CD FP-15: gro ss cystic d isease flu id protein 15; C EA: carcino em bryo nic antigen

Symptoms

Ten articles reported the most common presentation symptoms related to gastric metastasis: they are often non specific, with epigastric pain as the most frequently reported, followed by nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia and dysphagia. Other reported symptoms are anorexia, early satiety, weight loss, and bleeding that may manifest as hematemesis, melena or iron deficiency anemia. One article used the term “inexpressive” to describe these symptoms.

Endoscopy

All the studies reported the main endoscopic findings, and the majority of them agreed that the most common presentation is linitis plastica. Because linitis plastica is caused by the infiltration of tumor cells in submucosa, the overlying mucosa is normal, thus resulting in negative exam results in 50% of cases,as reported in two studies, or 30%, as reported by Ayantude. Two articles discussed different patterns ofpresentation, but they analyzed all gastric metastases from other primary tumors and not only the ones related to breast cancer.

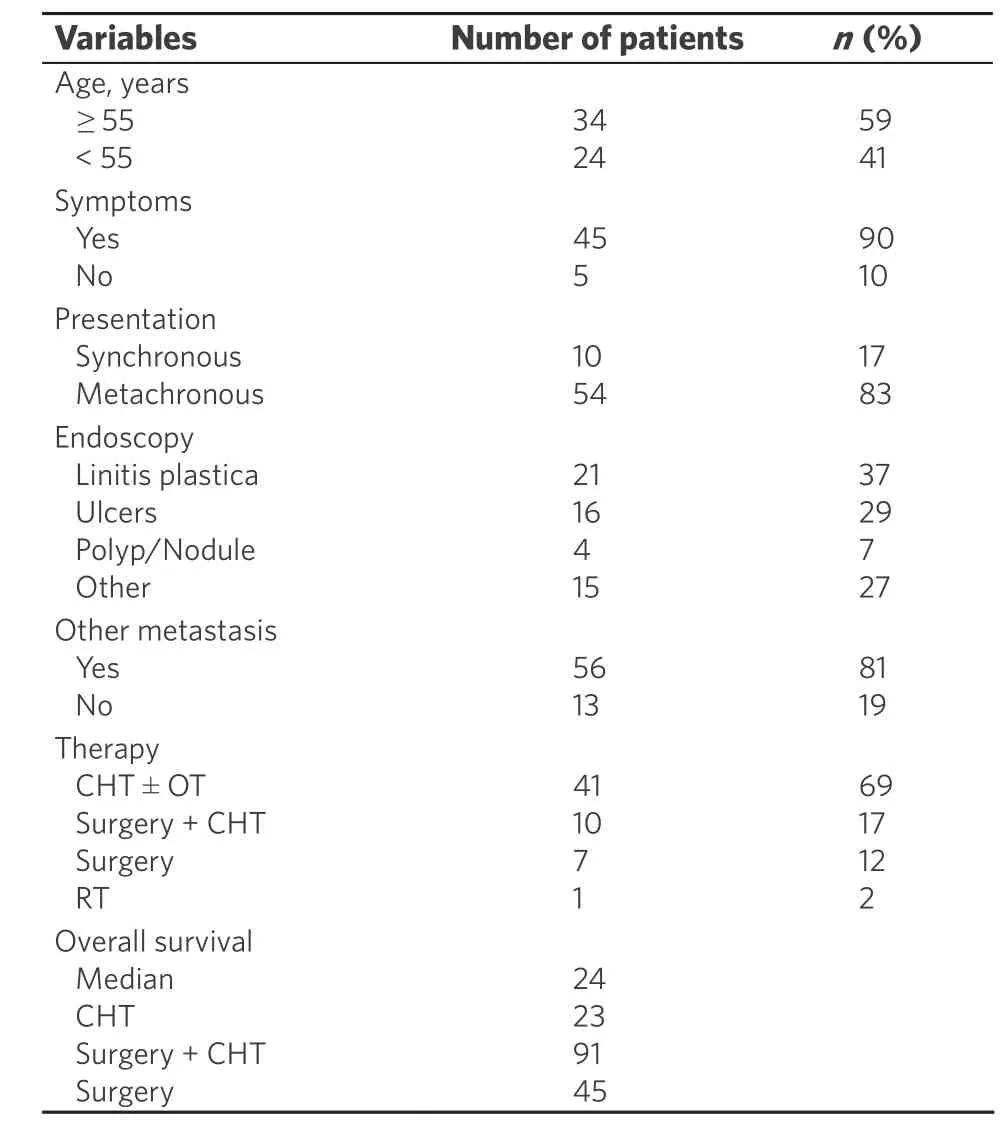

Table 2. Characteristics of patients

Table 3. Characteristics of primary breast cancer

Alternative instrumental tools

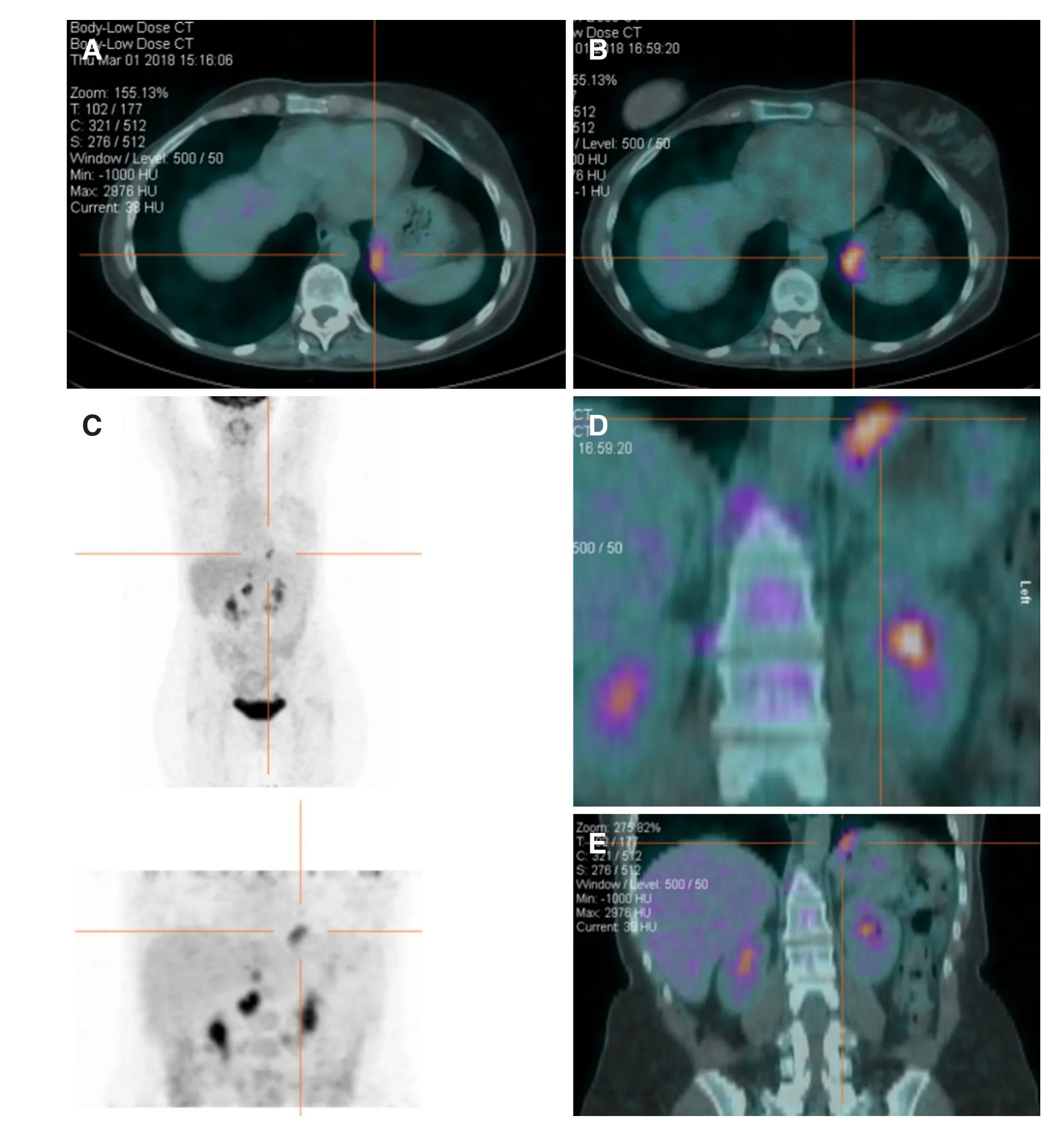

Other instrumental tools were not frequently cited. Ayantude and Aurello mentioned that computed tomography (CT) is commonly used to evaluate thickened visceral wall or the presence of other metastases.Namikawa observed that PET has a low sensitivity in diagnosing metastasis, but it may be useful to evaluate response to treatment in those tumors with intense FDG (F-18 fuorodeoxyglucose) uptake.

Gastric biopsy/histology

Two articles reported that gastric biopsy may be negative in 30% or even in 50% of the cases because the tumor cells infiltrate the submucosal layer and not the mucosal layer, which shows a normal histological aspect; there is thus a need for performing deeper biopsy in order to study also underlying layers, which is essential in this particular metastatic pattern. The most common reported histological pattern is signet ring cells, as cited in seven articles, which in some cases may be confused with tumor of gastric origin.

Gastric metastasis receptor

Immunohistochemistry is essential for differentiating gastric metastasis from primary tumor; positivity for estrogen and progesterone receptors in gastric metastasis is reported in seven articles, and they are the main receptors that direct the diagnosis to a secondary tumor of breast origin. Metastases of breast tumoralso show positivity for other receptors, such as CK7, CK18, GCDFP-15 and CEA, which are reported in five articles, and they are negative for CK20 and CDX2,which are usually expressed in intestinal cells, and also negative for E-cadherin and HER2, indicating a probable lobular breast cancer origin.

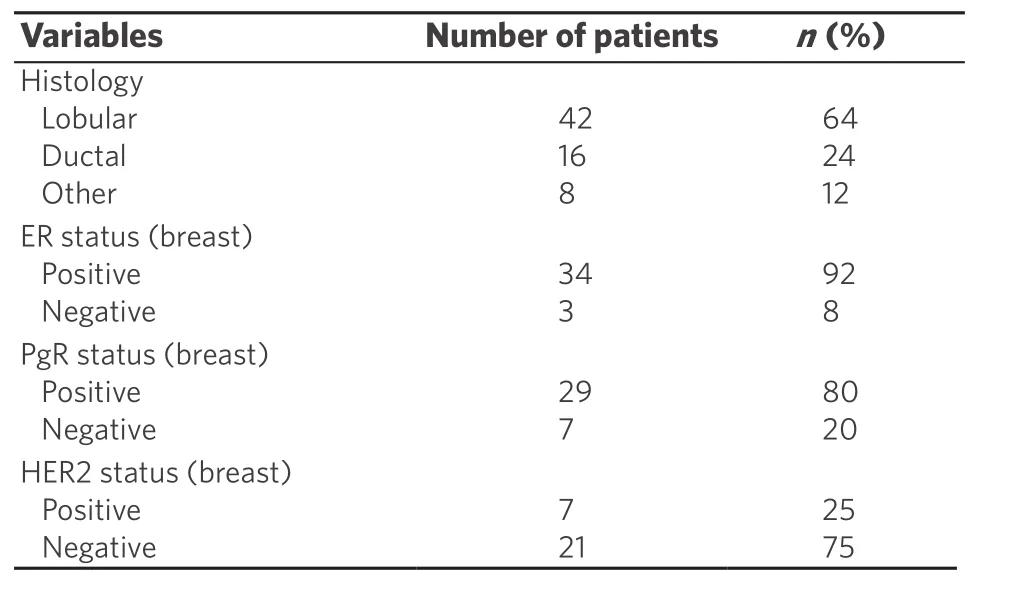

Table 4. Characteristics of gastric metastasis

Therapy/Surgery/Palliation

Ten articles reported that the main therapy for gastric metastasis from breast origin is systemic therapy,either chemotherapy or hormonal therapy; surgery is reserved only in case of complications or emergency,such as bleeding, perforation or obstruction. In this latter case, a more conservative approach is advised and three articles suggest to perform a simple bypass instead of a gastrectomy. Endoscopy can prove very useful and must be considered before surgical approach in case of obstruction and bleeding to put stents or to perform dilatation; also bleeding can be managed conservatively either with endoscopic hemostatic procedures or by embolization radiologists.

Survival

Only two articles mentioned overall survival and they are approximately concordant, with Jones reporting a survival of 28 months, and Aurello reporting 2 years.

Part 2. Case reports

We also performed a review of the literature focusing on case reports of gastric metastasis from breast cancer from January 1st 2013 to October 31st 2018 because we wanted to update the aforementioned reviews with the latest current clinical practice present worldwide. We found 36 reports for a total of 69 patients. Data were not reported entirely in all the case reports, so we analyzed and compared only mentioned data. All the patients were females except one male[43]. The median age of the patients was 58 years, with a range from 33 to 86 years. For the case reports that reported the age of the patients, 34 (59%) patients were > 55 years old,whereas 14 (41%) were < 55 years.

Breast tumor/receptor

The most common histological type of breast cancer was ILC (invasive lobular cancer), that was found in 42 cases (63%); other histological type of breast tumor were IDC (invasive ductal cancer) in 16 (24%), mixed in 2 (4%), and tubular in 6 cases (9%). In one case[30]breast tumor was not found at instrumental research after the diagnosis of gastric metastasis. Breast cancer tumor had ER positive in 34 (92%) cases and negative in 3 (8%); PgR was positive in 29 (80%) and negative in 7 (20%), and HER2 was negative in 21 (75%) cases and positive in 7 (25%). The most common receptor status is ER+/PgR+/HER2-.

Disease free survival

Usually gastric metastases from breast tumor occur several years after primary cancer; 54 (83%) patients had metachronous disease, whereas only 10 (17%) had synchronous tumors.

Time of presentation of gastric metastasis from primary breast cancer varies from 0.5 months to 20 years later, with a median time of 61 months (about 5 years). This explains the difficulty to reconduct the gastric disease to breast tumor, because in many cases there was a long time between the manifestations of the two disease.

Symptoms

Gastric metastasis mostly presented with non specific symptoms in 45 cases, such as epigastric pain (28),nausea and/or vomiting (14), dyspepsia (3), dysphagia (3), anorexia (5), weight loss (12), hematemesis or melena (13), anemia (3). Five patients[24,37,49]were totally asymptomatic, and diagnosis of gastric metastasis in these cases was incidental during exams in follow up. In one case[37]elevated CEA and CA15-3 rose suspiciously for metastasis and then PET scan confirmed gastric localization.

Endoscopy

At endoscopy the most common presentation was linitis plastica, present in 21 cases (37%), whereas ulcers were found in 16 cases (28%). In three of these latter cases[27,28,41]the first presentation was perforation, which resulted in elevated morbidity and mortality. Polips or nodules were present in 4 patients (7%).

Gastric tumor/receptor

Histological study of gastric metastasis showed in the majority of cases adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells. In six (9%) patients initial gastric biopsies suspected a primary gastric cancer so they were submitted to surgical treatment; only after histological study of the specimen it was clear that they were metastases from breast cancer and not primary tumor of the stomach.

Immunohistotype is essential to diagnose and differentiate primary gastric cancer from metastatic tumor;the mainly studied receptors were ER, that was positive in 50 (91%) cases and negative in 5 (9%); PgR, positive in 28 (61%) cases, and negative in 18 (39%); HER2 negative in 25 (70%) and positive in 11 (30%); CK7 positive in 21 (91%) and negative in 2 (9%) cases; CK20 negative in 20 (95%) and positive in only 1 case (5%); CDX2 negative in 7 cases (100%); GCDFP-15 positive in 9 (75%) and negative in 3 cases (25%); GATA-3 positive in 4 cases, Mammoglobine positive in 6 cases (86%) and negative in 1 (14%); E-cadherin positive in 3 (37%) and negative in 5 cases (63%).

In 45 cases immunohystological study of the biopsies from gastric lesions or gastric wall were taken before starting any treatment; considering patients who underwent gastrectomy, nine[23,26,27,28,35,42,43,45]were taken after surgical treatment whereas three[23,28,43]were done before, but authors decided to perform surgery because they suspected primary gastric cancer or they couldn’t exclude it.

In two patients[22,43]immunohistological pattern of gastric metastasis was different from the one of primary breast cancer; in one patient[40]pattern changed during treatment history, passing to a luminal A type and then to a triple negative.

Other metastasis

Gastric metastasis is usually part of a systemic disease and presents with other localization of malignant cells; considering all case reports, 56 patients (81%) presented with other metastases at time of diagnosis.

Therapy

The preferred treatment is systemic therapy, as chemotherapy, endocrine therapy or a combination of both of them; 41 of the patients were subjected to chemotherapy with or without hormonal therapy. Combination of surgery and chemotherapy was used in 10 patients[23,28,29,35,37-39,41,43,45]; two of them[28,29]were submitted to neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery in the belief of a primary gastric cancer. Surgical treatment alone was chosen in 7[26,27,42]patients, with three[27,42]of them in an emergency setting for bleeding and perforation. Endoscopic stenting for obstruction was used successfully in 2 patients[19,22].

Survival

Median overall survival was 24 months, in line with data given by current literature. In some papers survival at follow up was the only data cited, and the media of these data was 28 months. Patients submitted to chemotherapy had an OS of 23 months; patients subjected to surgical treatment alone had an OS of 45 months.Those subjected to surgery plus chemotherapy had an OS of 91 months. We must consider the fact that for this latter group only two patients were considered and that they had stomach as the only site of metastasis.However, due to the paucity of number of cases considered, this data can be misleading.

Part 3. Comparison between reviews and case reports

The final results from the review and the case reports show that the breast cancer that is responsible for most of the metastasis is the lobular type (83%vs.63%). Both summaries report that the time of presentation of gastric metastasis is very variable, and ranges from few months to many years (20 yearsvs.30 years), and that median disease free survival is 5 years.

Symptoms related to gastric metastasis are reported in both studies as non specific, such as epigastric or abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting, dysphagia, dyspepsia, anorexia, weight loss, and bleeding that may manifest as hematemesis, or melena or anemia. Interestingly, in five patients[24,37,49]of case reports there were no symptoms and diagnosis of gastric metastasis was based on other signs, such as elevated serum markers or incidental findings at instrumental routine follow up.

Regarding endoscopic findings, the principal pattern is linitis plastica in both studies; reviews say that in 30%-50% of cases endoscopic findings are negative, but this aspect is not present in the majority of case reports.

The most common histological pattern found in gastric metastasis is adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells; this pattern can be confused with primary gastric cancer, as said in the reviews; indeed in three case reports[37-39]preoperative findings showed this pattern on gastric biopsies and surgical treatment was performed.

Immunohistochemistry is mainly based on expression of ER and PgR. They are reported as positive in reviews, and, in the case reports, 50 (91%) tumors had ER positive and 28 (61%) had PgR positive; other receptors are HER2 and E-cadherin, whose absence is related to lobular cancer (negative in reviews, in case reports 25 (70%) tumor had HER2- and 5 (63%) had E-cadherin-); positivity for CK7, GCDFP-15 and MGB and absence of CK20 and CDX2 are also related to breast cancer origin. Systemic therapy is the treatment of choice in the reviews and even in case reports (used in 41 patients). Surgery is usually performed in case of complications such as perforation or bleeding; in three cases patients were submitted to emergency laparotomy, two[28]for perforation and septic shock and one[42]for bleeding and hemorrhagic shock. Main surgical intervention is gastrectomy (performed in 13 patients), whereas in one patient[41]only raffia and biopsy were performed in the setting of a perforation. Bypass, that is considered the best option according to reviews, was not even considered in case reports. Indeed obstruction can be managed conservatively by endoscopic stenting as mentioned in reviews, and this was performed in two patients[19,22]. No embolization was performed in case reports. Median overall survival is similar (about 2 years) in the two summaries.Unfortunately reviews didn’t subdivide OS by type of treatment.

DISCUSSION

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women and the leading cause of cancer-related death in female gender. Global incidence increased about 3.1% every year in the past 30 years, with an increase of the number of cases in Middle East, south Asia, southeast Asia, and central Latin America, and also mortality increased at an annual rate of 1.8%[1]. Malignant proliferation may arise from ductal or lobular ephitelium:the most frequent is the ductal type that includes 75%-82% of all cases[4,52,53]. Other less frequent types are lobular carcinoma (4%-10% of all cases), phylloides, or tubular cancer.

Metastases are possible either in ductal and lobular carcinoma, but they may develop in different organs:ductal carcinoma metastatizes more frequently to the lung, the brain and the liver, whereas lobular cancer tends to metastatize to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, gynecologic organs, peritoneum and bones[2,3]. Breast cancer, melanoma and lung cancer, represent the most frequent malignancies metastatizing to GI tract[15,16,53]:the common sites of GI metastasis from breast tumor are colon and rectum (45%), stomach (28%), small intestine (19%), and esophagus (8%)[53]. Median overall survival of patients with gastric metastasis ranges from 24 to 36 months[53].

Incidence

Gastrointestinal metastases from breast cancer are rare, among them the stomach is the second most common site. In McLemoreet al.[53], 2005 study, which regarded 12,001 patients, gastric involvement represents 28% of all cases. The incidence of breast cancer metastasis to the stomach is reported to be from 0.1% to 6%, but in autopsy series the estimated incidence is found to be higher, from 5% to 18%[3,4].Gastrointestinal metastases are usually associated with other concurrent tumor localization: in a retrospective study lead by Taalet al.[3], 1992 up to 94% of patients present with disseminated disease, that involve the skeleton (60%), liver (20%), and also the lung (18%)[4]. In our study 81% of the patients had other metastases at time of diagnosis.

Metastasis

Gastrointestinal metastasis from breast cancer can be synchronous or more frequently metachronous,with a mean time of presentation reported to be from 6 to 7 years[5], but in literature time can vary from 2 to 30 years[5,6]. In our study there were 54 cases with metachronous presentation and only 10 patients with synchronous disease.

Studies report three main mechanisms of dissemination of malignant breast cells to the upper GI tract:lymphatic spread, hematogeneous route, and direct invasion from surrounding organs[3,4,54,55]. The first type is more common in esophageal metastasis: the typical presentation is stricture or submucosal nodules with normal overlying mucosa, that makes endoscopic diagnosis difficult[54,55]. Also the infiltration of paraesophageal lymphonodes can result in compression of the esophageal lumen with consequent intramural infiltration[56]. Hematogenous spread is typical of esophagus, stomach or duodenum which results in stenosis or mass localized intramural or in the submucosal layer, that may become ulcerated. The most common pattern of presentation is linitis plastica-like; in this situation malignant cells are trapped from blood stream to the submucosal or subserosal layer with diffuse infiltration that cause diffuse thickening and rigidity of the organ wall[4,54,55,57].

An important role in metastatic pathway is played by chemokines. CXCR4 and CXCR7 are the main chemokine receptor expressed in breast cancer cells involved in transendothelial migration (TEM), and they are responsible for the chemotaxis to certain target organs[58]. CXCR4+ tumors are associated with more distant metastasis than CXCR4-tumors, even though this association is not statistically significant[59]. Their ligandsareCXCL12 and CCL21; the first is implied in modulating integrin expression, metalloproteinase production, tumor angiogenesis, tumor cell adhesion and apoptosis[60,61]. Metalloproteinases are essential to degrade extracellular matrix to permit invasion of the cells attracted in metastatic sites by chemokines from the bloodstream[60]. CXCL12 promotes homing of tumor cells to secondary sites and then recall endothelial stem cells for blood vessel formation and subsequent proliferation[61].

Circulating breast tumor cells pass from blood or lymphatic stream to areas that express CXCL12, thereby metastatizing in many organs such as bone marrow, lymph nodes, liver and lung[59,61].

An interesting hypothesis suggested by an article by J. Carlos Villa Guzman highlights the implication of infammation response in tumorigenesis. Chronic infammation induced by Helicobacter Pylori is associated with higher expression of chemokines and interleukins that may attract tumor cells to gastric or colon mucosa with subsequent proliferation and develop of metastatic disease[9]. Even though these mechanisms are not fully understood, this hypothesis offers an interesting start point for other future studies.

Lobular breast cancer

Breast cancer metastases are more frequently related to lobular type then ductal type; in 83% of all metastases the primary breast cancer has lobular histotype[4]. According to the study of Borstet al.[62], 1993 the incidence of lobular carcinoma metastasis is higher in organs such as gastrointestinal system (4.5%vs.0.2% in ductal carcinoma); gynecologic organs (4.5%vs.0.8%); peritoneum-retroperitoneum (3.1%vs.0.6%); bone marrow(21.2%vs.14.4%). We found 42 cases with gastric metastasis from lobular carcinoma,whereas 16 cases were related to ductal carcinoma. The propensity of lobular breast cancer to give metastasis seems to be correlated with mutations of E-cadherin genes; the impaired function of the produced protein determines loss of adhesion among epithelial cells. Cells are initially separated from each other so that they can invade the surrounding tissue and then enter in the lymphatic system or in the bloodstream, leading to the progression of metastatic disease[63,64].

Symptoms

Gastric metastases of breast cancer have no specific symptoms and may often be confused with primary gastric cancer or other conditions, such as effects of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, oral medications, liver metastasis or hypercalcemia[4,57]. These symptoms include anorexia, dysphagia, feeling bloated soon after eating, bleeding (melena, hematemesis), dyspepsia, epigastric pain and retch[65,66]. Common findings in blood tests are iron deficiency anemia or abnormal high levels of CA 15.3 that would arise the suspect for a relapse of primary breast cancer[9,67]. Gastric metastases usually occur many years after primary breast cancer,so when the patient presents with these vague symptoms it’s difficult to reconduct them to the primary causative disease. In our case reports, nine[23,28,29,35,37,38,39,43,45]of the patients had a wrong initial diagnosis and they were submitted to surgical treatment in the suspect of a primary gastric cancer.

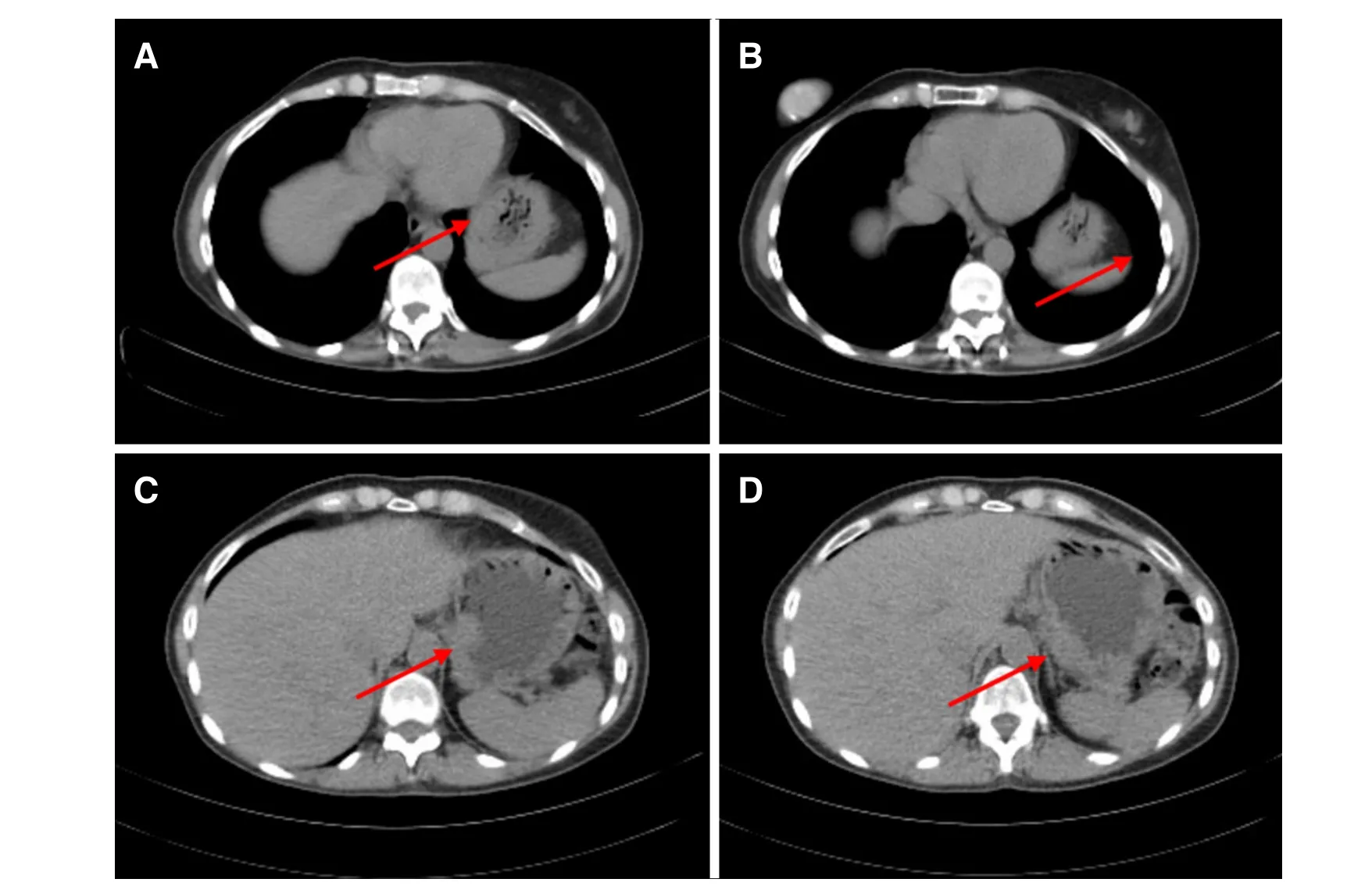

Diagnosis (instrumental)

Endoscopy is the main diagnostic tool when patients present with symptoms related to upper GI disease.Gastric metastases from breast cancer show three main different patterns: localized pattern (in about 18% of cases, as large ulcers and polyps [Figure 1], diffuse infiltration (57% of cases, such as linitis plastica-like with diffuse infiltration of the submucosal and seromuscolar layer with a fibrotic reaction that causes narrowing lumen, rigidity, wall thickening with reduced peristalsis), and external compression (in 25% of cases)[4,68,69].Gastric metastases are usually localized in submucosal and seromuscolar layers; in more than 50% of cases endoscopy study is negative[70]. In one case report[18]first histological examination of gastric biopsies was negative; after synchronous diagnosis of primary breast cancer, endoscopy was repeated and biopsies of submucosal layer were performed again, showing gastric metastasis from lobular cancer. Also in another patient[19]initial gastric biopsies were negative, reporting only mild chronic gastritis. Endoscopic ultrasound showed thickening of the muscolaris propria so biopsies were repeated focusing on this layer: muscular wall was infiltrated by malignant cell from lobular breast carcinoma.In literature CT scan study is not mentioned as one of the main diagnostic source to establish the nature of primary cancer, but it is used to evaluate wall thickening despite a normal aspect in endoscopic study and other site of metastasis[54][Figure 2].

Figure 1. Endoscopy showing localized lesion at gastric corpus. Biopsy confirmed the presence of gastric metastasis from breast cancer

A new useful diagnostic approach to differential diagnosis is magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI); it shows alterations in the framework of microvessels that are characteristic of metastatic pattern in comparison to primary malignancy of the stomach[51].

The sensitivity of PET is lower for the diagnosis of gastric cancer due to physiological absorption of F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose and involuntary movements by the gastric wall [Figure 3]; early cancers, signet-ring cell carcinoma and poorly differentiated non-solid adenocarcinoma are characterized by high false-negative rates. There are also some scenarios of non-specific FDG accumulation correlated to mucosal infammation,as in superficial gastritis and erosive gastritis, leading to false positives[71].

Histology

Differentiation of primary gastric cancer from gastric metastasis is crucial; from the histological point of view, the first important difference is the localization of tumor cells: mucosa is generally involved in gastric cancer, while submucosal layer is usually affected in metastatic disease[4,15]. In gastric metastasis malignant small cells with monomorphic, round nuclei and vacuolated cytoplasm typically array in chords, named“Indian files”, and infiltrate the serosal, muscular and submucosal layer[57].

An additional difficulty is that they share signet ring cell-like morphology, thus lobular metastasis can mimic primary gastric cancer. However breast signet-ring cell carcinoma may show some morphological differences from gastric and colonic signet-ring cell carcinoma. The first shows a single, well-circumscribed univacuolated intracytoplasmatic lumina, with a central eosinophilic inclusion, whereas the latter has an extended, globoid, and optically clear cytoplasmatic acid mucin that pushes the nuclei against the cell membrane[72].

Figure 2. CT scan showing gastric wall thickening at gastric fundus (A-D)

Therefore differentiation of primary gastric metastasis requires to evaluate the infiltration of the serosal,muscolar and submuscolar layers by cells that organize in a typical Indian file pattern[57]with a signet ring appearance[73].

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis is the most important tool for differentiating between primary gastric cancer and gastric metastasis from breast cancer; the main markers currently employed are estrogen receptor (ER),progesterone receptor (PgR), mammaglobin (MBG), cytokeratin 7 (CK7), cytokeratin 20 (CK20), human ephitelial receptor 2 (HER2), gross cystic disease fuid protein 15 (GCDFP-15), and GATA-3. A new marker is HFN4A, which is discussed below.

Figure 3. Pet scan showing pathological F-18fluorodeoxyglucoseaccumulation in the gastric fundus (A-E)

The expression of ER and PgR is highly indicative of breast carcinoma metastasis. Primary gastric cancer can express ER in up to 30% of cases and PgR in up to 20% of cases, but also gastric metastasis from breast carcinoma sometimes show negative ER and PgR rate even if primary breast cancer is ER and PgR positive[66,74]. Expression of ER, PR and HER2 status can change between primary tumor and metastatic lesions in up to 42% and this change does not correlate with an impairment of overall survival[75]: ER and PR status are different in 14.6% and 16.7% of cases respectively, while HER2 changes in about 8.3% of cases.During treatment it can be useful to take several biopsies to modify chemotherapy or endocrine therapy in the light of ER, Pr and HER2 status[70]. Following chemotherapy, in particular anthracycline-based ones, the level of expression of ER, PR and HER2 can change[75]; these modifications imply a change also in tumor progression and aggressiveness and a resistance to endocrine therapy or trastuzumab, producing a change in clinical strategy. In our study the male patient[43]had different patterns between gastric metastasis and primary breast tumor (ER-/PgR- in the stomach and ER+/PgR+ in the breast), one[22]had different expression of HER2 (HER2- in the breast, HER2+ in the stomach) and one patient[40]showed a change in receptor status during treatment passing from a Luminal A type to a Luminal B and then to a triple negative.

Combination of CK7/CK20 is also useful to distinguish between metastasis from breast carcinoma and primary gastric tumor; CK20 is expressed in gastric, colorectal, pancreatic and in transitional cell carcinomas, but it’s negative in breast cancer[76]. The CK7+/CK20- pattern is typical of adenocarcinoma of the breast, lung, and ovary, while CK7-/CK20+ is expressed in intestinal adenocarcinoma. CDX2 is a tumor suppressor gene that is implied in intestinal cell proliferation, differentiation, adhesion and apoptosis; it’s an important marker of intestinal differentiation, usually expressed in gastric cancer and in intestinal metaplasia[77,78].

Mammoglobine (MGB) is a 93-amino acid glycoprotein and a recent marker for breast cancer with a sensitivity of 93.1%. It can be useful in diagnosis of gastric metastasis from breast tumor in combination with other receptor expression[79,80]. GCDFP-15 is never expressed in gastrointestinal cancer, but it’s found in malignant tumor from the breast, and also salivary gland, external genitals, eyelid, apocrine duct of the bronchial tubes and gynecologic adenocarcinoma[81]. MGB is more sensitive than GCDFP-15 but has less specificity[79]. GATA-3 is a nuclear transcription correlated to breast glandular epithelial cells and shows the highest sensitivity in comparison to MGB and GCDFP-15[81].

Diagnosis of metastatic disease stems from the analysis of all these markers. Gastric metastases are usually positive for ER, PgR, mammoglobine, GCDFP-15, GATA-3 and CK7 and negative for CK20. Gastric cancer is normally positive for CK20, but it’s usually negative for GCDFP-15, ER and PgR, even if ER and PgR expression is controversial.

HNF4A (hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha) was introduced as a new marker to differentiate gastric metastasis from primary malignant tumor. HNF4A is a nuclear transcription factor correlated with invasion,metastasis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, due to activation of MMP-14 and promoting tumor angiogenesis, migration and invasion[82]. A recent Brazilian study shows that HNF4A has positive expression in all patients with primary gastric adenocarcinoma, negative in all cases of primary breast carcinoma and also negative in all gastric metastases from breast carcinoma. In combination with ER and PR expression, it exhibits high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (96%)[83].

Therapy

Establishing the primary site of malignancy determines the right treatment. Gastric metastasis from breast cancer are considered as a systemic disease because they usually present along with other metastatic localization, therefore the appropriate therapy is systemic, such as chemotherapy or endocrine therapy,whereas for primary gastric cancer first line therapy involves surgery[5,15,84]. Chemotherapy, hormonal therapy or a combination of both of them lead to a remission rate of 32% to 53% and a prolonged survival of 2 or 3 years[3].

In case of metastatic disease surgery is considered in case of obstruction, bleeding or perforation of gastric wall[85]even if more conservative treatments (endoscopic hemostatic procedures or stent) can be performed in patients with low performance status[12]. The surgical option must be as little invasive as possible, for example a palliative bypass can be considered in case of outlet obstruction[15].

Many studies, such as the one conducted by McLemoreet al.[53], 2005 report a lack of survival benefit from surgical treatment; palliative surgery can be associated with a prolonged median survival in some cases, but other factors can affect this difference such as biased patient selection for surgical palliation. In literature,few studies show surgical resection in patients with unique localization with reported improvement in overall survival: the study published by Taalet al.[4], 2000patients with complete remission of primary breast cancer that underwent gastric resection for solitary gastric metastasis shows a survival time of 38 months to be compared with 14.38 months for patients who didn’t undergo resection[3]. This can be explained considering that for patients submitted to surgical treatment the stomach is the unique localization without other metastasis or peritoneal carcinomatosis. In these patients the disease is not as advanced as in those candidates for systemic therapy. Therefore enhanced survival is due to patient clinical conditions and not strictly related to the type of treatment. In general, surgery does not offer an increase in survival but may have role in palliation[53]. In our study surgery was also used to perform final diagnosis; gastric biopsies were confounding, thus authors performed gastrectomy to rule out the origin of the gastric disease[23,28,29,35,37-39,43,45].

CDH1 mutation

As mentioned before, E-cadherin is a transmembrane glycoprotein involved in calcium-dependent adhesion; when E-cadherin is mutated, this leads to loss of cell adhesion, cell migration and subsequently tumorigenesis[86]. An important gene mutation that is both associated with breast cancer and gastric cancer is CDH1, that encodes E-cadherin. Families with CDH1 mutations have a cumulative risk of developing hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) of 70% and 56% in males and females, whereas female members have a cumulative risk of 42% for lobular breast cancer by age 80[87]. Other gene mutations related to breast cancer but not to gastric cancer are BRCA1, BRCA2, and TP53; both BRCA1 and TP53 are associated with invasive ductal carcinoma, BRCA2 with both ductal and lobular carcinoma while CDH1 is only associated with lobular breast carcinoma[88]. CDH1 is a gene mutation that is mutually exclusive with BRCA1/2 germline mutations. Screening for CDH1 should be suggested to women who have a personal or a family history of a combination of diffuse gastric cancer and lobular breast cancer (with at least one diagnosed before the age of 50), bilateral lobular carcinoma diagnosed at a young age, or family history of multiple lobular carcinomas with onset before 50 years old without gastric tumour[89]. Sometimes diagnosis of lobular breast cancer with early onset might be the first manifestation of HDGC; so in patients with a history of multiple LBCs at a young age, especially with bilateral manifestation, it’s advisable to perform a test for gene mutations[90]. When CDH1 mutation is diagnosed, therapeutic management for the stomach and the breast is quite different: usually prophylactic total gastrectomy is advised because of the high risk of DGC, whereas prophylactic mastectomy is not performed, considering various genetic penetrance for LBC, but female patients should undergo to yearly mammography and breast MRI from age 35 years onwards[86].

In conclusion, gastric metastases are a rare but not unusual site of secondarism from breast cancer[3,4]. They usually arise several years after diagnosis of primary tumor and sometimes this can mislead the diagnosis[5,6].The differential diagnosis between primary gastric cancer and gastric metastasis is crucial and made possible only by histology and immunohistological patterns. Systemic therapy is the treatment of choice because the disease is usually not only localized to the stomach but presents other concurrent metastases[5,15,84]. Surgery still has a role in case of complications or for definitive diagnosis when preoperative biopsy is not diriment and there is still a suspicion for primary gastric cancer[85], even though this latter case is progressively decreasing thanks to innovation in instrumental tools for diagnosis. Breast metastasis to the stomach should be considered in any patient suspected of gastric cancer previously treated for breast carcinoma, especially if the treated carcinoma was ILC.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and interpretation: D’Angelo F, Rampini A, Cardella S

Performed data acquisition: Rampini A, Cardella S

Performed administrative, technical, and material support: Nigri G, Valabrega S

Data review: Antonlino L, Aurello P, Ramacciato G

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conficts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication for images used in Figures 1-3 was obtained.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2019.

Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment2019年4期

Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment2019年4期

- Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment的其它文章

- AUTHOR INSTRUCTIONS

- Cancer stem cells in liver metastasis from colon adenocarcinoma express components of the reninangiotensin system

- Breast cancer, metastasis, and the microenvironment: disabling the tumor cell-tostroma communication network

- Sensitive and specific detection of circuIating tumor ceIIs promotes precision medicine for cancer

- Peripheral biomarkers for pediatric brain tumors:current advancements and future challenges

- Targeting autophagy with small molecules for cancer therapy