Sarcopenia in pancreatic cancer-effects on surgical outcomes and chemotherapy

Miu Yee Chan,Kenneth Siu Ho Chok

Abstract

Key words: Sarcopenia; Pancreatic cancer; Clinical outcomes; Surgical outcomes;Chemotherapy; Radiotherapy

INTRODUCTION

The topic of sarcopenia in pancreatic cancer has come under the spotlight in the past decade.With the updates on several consensus statements,including those from the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia in 2016[1]and European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) in 2018[2],it is now known that sarcopenia is a condition that not only relates to age but is also affected by multiple factors,such as systemic inflammation,physical inactivity,and inadequate intake.The relationship between pancreatic cancer and cachexia has long been recognized,but it is only in the last decade that researchers have started to understand the importance of sarcopenia.

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most deadly malignancies worldwide,with a 5-year survival of only about 5%,despite numerous efforts to improve various therapeutic strategies over the decades[3].It has become the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and is projected to become the second by 2030[4].Among pancreatic cancer patients,those who have undergone resection have much better survival rates than those who are unresectable[5].Unfortunately,less than one-fifth of patients with this malignancy are considered resectable[3].The low resection rate is due to unfavorable tumor stage and location and also to comorbidities and poor functional performance of patients[6].In pancreatic cancer patients,poor oral intake,altered metabolism due to malignancy,and malabsorption because of obstruction or exocrine insufficiency can all come into play at the same time and contribute to both cachexia and sarcopenia[7].These in turn worsen the patients' performance status and their suitability for surgery.

In various studies,the prevalence of sarcopenia in pancreatic cancer patients ranges from 30% to 65%[8-10].The wide variation is likely due to the heterogeneous groups of patients,difference in disease stage,and different methods of measuring sarcopenia[1,7,11].Despite these variations,it has been repeatedly shown that sarcopenia patients are more likely to have poorer outcomes[12-14].This article aims to examine the current evidence on sarcopenia,as well as its impact on the management of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

DEFINITION OF SARCOPENIA

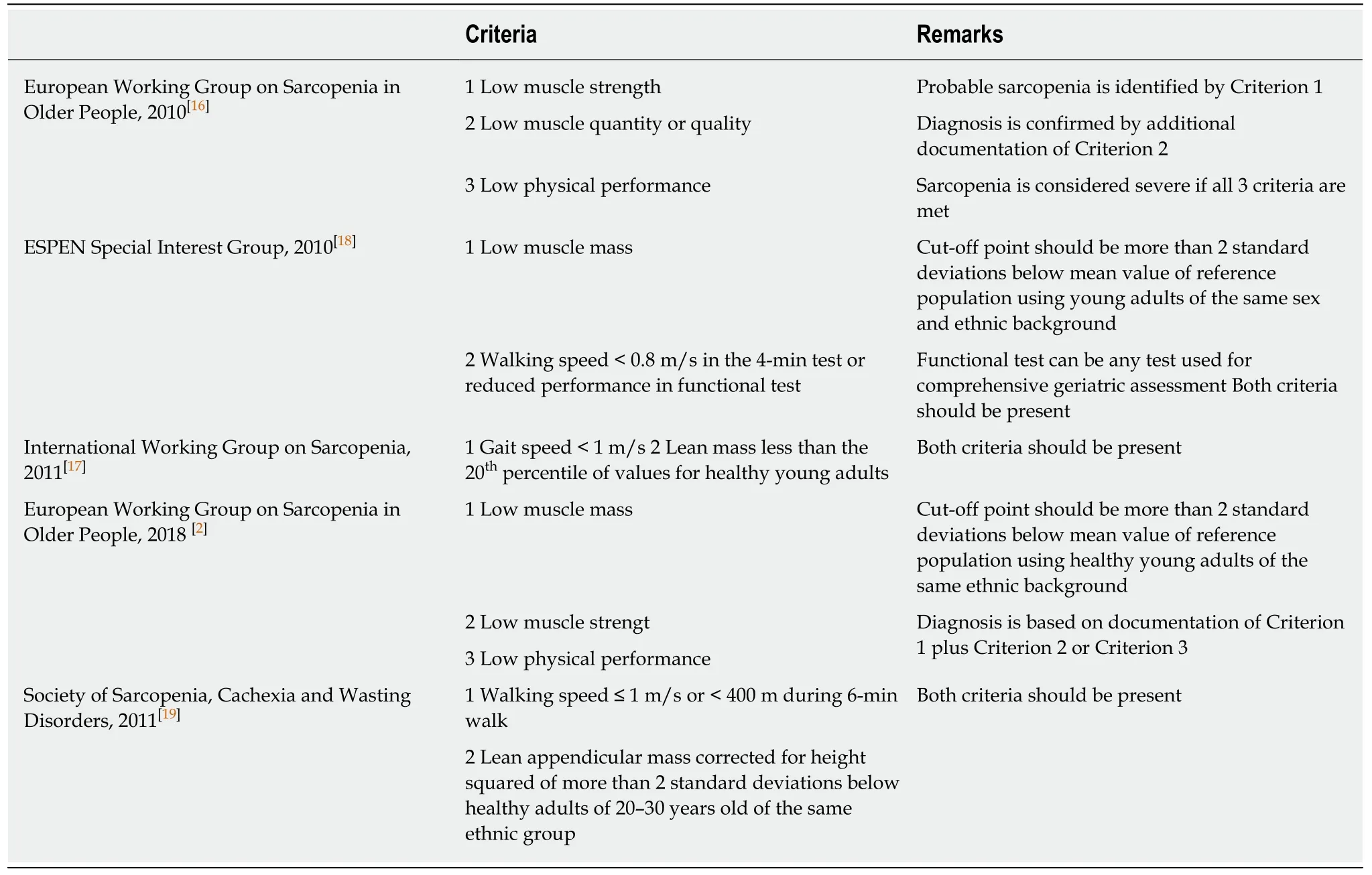

Since the term “sarcopenia” was coined by Rosenberg[15]in 1997,remarkable progress has been made in understanding this condition and its relationship with malignancies and surgery.Instead of merely detecting the decline in muscle mass,EWGSOP redefined the condition in 2010 as the syndrome characterized by progressive and generalized loss of both skeletal muscle mass and quality (strength or performance)with a risk of adverse outcomes[16].In the latest consensus by EWGSOP in 2018[2],muscle strength has come to the forefront in the diagnosis.From the evolution of the definition,it is clear that more emphasis has been put on muscle quality over quantity over the years.Similar definitions have been put forward by other groups,including the International Working Group on Sarcopenia[17],the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) Special Interest Group[18],the Society of Sarcopenia,Cachexia and Wasting Disorders[19],and the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia[20].According to these definitions,the assessment of both muscle quantity and muscle quality is required when diagnosing sarcopenia (Table 1).

ASSESSMENT OF SARCOPENIA IN PANCREATIC CANCER PATIENTS

Despite the relatively unified definition from different consensus groups,there is a wide array of assessment tools for sarcopenia.Each tool differs in applicability in research settings,clinical settings and primary care settings.Since different studies utilized different tools for assessment and there is no unified cut-off value,the interpretation and comparison of results across different studies is particularly difficult.

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia by various working groups

The traditional way to determine appendicular lean muscle mass is dual-energy Xray absorptiometry[21-23].However,it is less sensitive in evaluating intramuscular fat,which can make up 5%-15% of muscle mass in obese people[24].Other methods such as bioimpedance analysis and urinary metabolites have also been mentioned in the literature[25]but are subject to error.As most patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer would have had cross-sectional imaging such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging,most of the studies used these scanning methods to diagnose sarcopenia.Both computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging have been shown to be more sensitive to small changes in muscle area than dualenergy X-ray absorptiometry[23,26]and are now considered to be the gold standard for evaluating muscle mass[27].

There are a number of measurements that can be taken from cross-sectional imaging.The areas of fat,fat-free and lean muscle can be calculated with the specific Hounsfield unit[27]and then converted into whole-body fat mass,fat-free mass and lean muscle mass[28].The most commonly used landmark is the cross-sectional area of muscle at the L3 vertebra,and there are studies showing that the measurement at this level significantly correlates with whole-body muscle mass[28,29].There are also other measurements such as the cross-sectional area of the psoas muscle[30]and the volume of the psoas muscle[31],but some researchers opined that these measurements might not be representative enough to be a surrogate marker,as the psoas muscle is a minor muscle[32].It is important to examine which measurement was used in a study,as well as whether the results were adjusted for height,weight or body mass index.As suggested by EWGSOP[2]and the ESPEN Special Interest Group[18],the cut-off point for the measurements should be more than two standard deviations below the mean reference value of healthy young adults of the same sex and same ethnicity.

As mentioned above,sarcopenia is not only defined by a decrease in muscle mass.As in osteoporosis,where an increase in bone mass does not necessarily translate into a lower fracture risk,an increase in muscle mass does not translate into better physical performance.Physical performance is a combination of many aspects,and muscle quantity is only a small part of it.Other aspects,including muscle quality,strength,power,motor control and coordination all play a part.Therefore,a decline in muscle strength or power should be documented.There are simple methods to assess muscle strength and power,such as handgrip strength with dynamometry and sit-to-stand time[2,33].According to EWGSOP in 2018[2],physical performance should also be assessed by a test such as gait speed,400-meter walk test,or the short physical performance battery[34].Although there may be certain limitations in these tests,like in patients with mobility problems due to orthopedic or neurological problems,attempts should be made to include these parameters when discussing sarcopenia.However,in the current available studies on pancreatic cancer patients,these parameters were rarely included (Table 1).Therefore,the true prevalence of sarcopenia in the study populations may still be unknown.

IMPACT OF SARCOPENIA

Surgical resection remains as the only potentially curative treatment for pancreatic cancer.The evolvement of operative techniques and perioperative care has lowered the perioperative mortality rate to 3%-5% at high-volume centers and the morbidity rate to about 40%[35].Despite the advances in surgery and the combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy,the median survival after resection and chemotherapy is only around 30 mo,with a 5-year survival rate of around 30%[36,37].Therefore,there has been ongoing research trying to identify the risk factors for such poor outcomes,and sarcopenia is a factor being investigated.

Surgery

Perioperative outcomes:A study by Penget al[14]in 2012 is one of the earliest studies reporting the relationship between sarcopenia and surgical outcomes of pancreatic cancer.The study included 557 patients who underwent pancreatic surgery for pancreatic cancer,and 139 of them (25.0%) were found to be sarcopenic after measurement of their total psoas area.Sarcopenic and non-sarcopenic patients had no statistically significant difference in hospital stay,intensive care unit stay,or overall morbidity rate.Sarcopenia was not associated with increased hazard of 90-d mortality[hazard ratio [HR] 2.31,95% confidence interval (CI):0.78-6.77;P= 0.13].

Such discrepancy in results was likely partially due to the different assessment parameters used.It is important to bear this in mind when interpreting results from different studies.For example,Pecorelliet al[38]reported that sarcopenia,as defined by Pradoet al[39]using total abdominal muscle area (TAMA),was not a significant prognostic factor for 60-d postoperative mortality (P= 0.224).However,the ratio of visceral fat area (VFA) to TAMA was found to be a significant predictor for 60-d mortality when the ratio was > 3.2 in multivariable analysis [odds ratio (OR) 6.76,95%CI:2.41-18.99;P< 0.001].Similarly in another study by Aminiet al[31],total psoas volume was used instead of total psoas area in patients who underwent curative surgery.With a different assessment tool,they were able to show that sarcopenia was associated with adverse short-term outcomes.While sarcopenia based on total psoas area was not associated with morbidity after operation (OR 1.06,95%CI:0.77-1.47;P=0.72),sarcopenia based on total psoas volume was found to be associated with a significantly higher complication risk (OR 1.79,95%CI:1.25-2.56;P= 0.002) and significantly longer intensive care unit stay (P= 0.002).

Meta-analysis by Ratnayakeet al[40]reported that there was no statistical difference in the incidence of delayed gastric emptying (sarcopenic 19%vsnon-sarcopenic 17%,95%CI:0.80-1.29;P= 0.895),postoperative bile leakage (sarcopenic 7%vsnonsarcopenic 7%,95%CI:0.61-1.71;P= 0.933),surgical site infection (sarcopenic 17%vsnon-sarcopenic 22%,95%CI:0.75-1.16;P= 0.518),or morbidity of Clavien-Dindo grade 3 or above (sarcopenic 30%vsnon-sarcopenic 24%,95%CI:0.86-1.14;P= 0.869).The only significant difference was in postoperative hospital stay,which was longer in the sarcopenic group (mean difference 0.73 d,95%CI:0.06-1.40;P= 0.033).However,some studies in this meta-analysis included patients receiving pancreatic surgery for both benign and malignant conditions,and not all studies used the same parameters to diagnose sarcopenia.Overall,the impact of sarcopenia on short-term surgical outcomes did not seem significant,but further research in this area is needed to have a more definitive answer.

Postoperative pancreatic fistula:Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is one of the most concerning complications in patients undergoing pancreatic surgery.There were a number of studies that examined the relationship between sarcopenia and pancreatic fistula.Nishidaet al[41]measured the skeletal muscle index [skeletal muscle area at L3/(body height)2] of 266 patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy.A total of 61.3% of patients had pancreatic malignancy.The authors reported a significantly higher rate of major complications (Clavien-Dindo grade 3 and above)and,specifically,a higher rate of POPF (sarcopenic 22.0%vsnon-sarcopenic 10.4%;P= 0.011) in sarcopenia patients.Sarcopenia was also a significant independent risk factor for clinically relevant POPF (OR 2.869,95%CI:1.329-6.197;P= 0.007) in multivariate analysis taking into account factors including body mass index,presence of pancreatic tumor,portal vein or superior mesenteric vein resection,diameter of the pancreatic duct,and consistency of the pancreas.

In the study by Pecorelliet al[38]in 2016,202 patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy were included.The VFA and TAMA at L3 on computed tomography were measured.A high VFA-to-TAMA ratio was associated with 60-d mortality by multivariate analysis (OR 6.76,95%CI:2.41-18.99;P< 0.001).Only a large VFA,but not TAMA or VFA-to-TAMA ratio,was associated with POPF (OR 4.05,95%CI:1.85-8.84;P< 0.001).Although a relationship between TAMA and POPF could not be identified,a VFA-to-TAMA ratio > 3.2 was shown to be predictive of a higher mortality risk (OR 6.33,95%CI:1.37-29.21;P= 0.018) in the subgroup of patients with major complications.

In the meta-analysis by Ratnayakeet al[40],which included 13 studies involving 3608 patients,six studies reported on POPF.There was no difference in the incidence of POPF between the sarcopenic and non-sarcopenic groups [risk ratio (RR) 1.05,95%CI:0.68-1.61;P= 0.843].Two of these studies reported on patients with sarcopenic obesity.Yamaneet al[42]analyzed the ratio of visceral adipose tissue area to skeletal muscle index of 99 patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy.Multivariate analysis showed that a ratio ≥ 2.0 was one of the independent risk factors associated with clinically significant POPF (grade B or C).In another study by Sandiniet al[43],the VFA-to-TAMA ratio was measured in 124 patients.It was reported that the rate of POPF was slightly higher in patients with sarcopenic obesity after pancreaticoduodenectomy,but it did not reach statistical significance (46.7%vs32.3%;P=0.103).This may imply that sarcopenia alone is not associated with POPF,but patients with sarcopenic obesity may have a higher risk of POPF.

Long-term survival:In the study by Penget al[14]in 2012 cited above,the 3-year survival rates of men (non-sarcopenic 39.2%vssarcopenic 20.3%;P< 0.05) and women (non-sarcopenic 40.8%vssarcopenic 26.1%;P< 0.05) were both significantly lower in the sarcopenic group.Sarcopenia was found to be associated with 3-year mortality in both univariate (HR 1.68,95%CI:1.34-2.11;P< 0.001) and multivariate analyses (HR 1.63,95%CI:1.28-2.07;P< 0.001)[44].

Table 2 is a summary of long-term survival outcomes in sarcopenic patients from eight studies.In the study by Aminiet al[31],a low total psoas volume was found to be associated with worse survival (HR 1.72,95%CI:1.36-2.19;P< 0.001).Similar results were obtained by Okumuraet al[45],who used the total psoas index at umbilical level rather than at L3.Overall survival and disease-free survival were both significantly lower in the sarcopenic group (median overall survival:sarcopenic 17.7 movsnonsarcopenic 33.2 mo;P< 0.001; actual median disease-free survival not available;P<0.001).There were also studies that did not find any significant difference between sarcopenic and non-sarcopenic patients,such as the studies by Joglekaret al[46]and Van Dijket al[47].

Most of the studies in Table 2 used measurements from total psoas area or total psoas index for comparison.However,the cut-off points for sarcopenia varied widely.Some studies,such as the one by Van Dijket al[47],did not find any significant results with more commonly used parameters (TAMA) but had significant findings using values derived from computed tomography (radiation attenuation of skeletal muscle).Whether this indicates a low sensitivity of the initial parameter requires further investigation.

Mintziraset al[48]conducted a meta-analysis including 11 studies of pancreatic cancer and sarcopenia and concluded that the hazard of death was 1.4 times higher in sarcopenic patients (summary adjusted HR 1.35,95%CI:1.18-1.54),and the hazard was even higher for patients with sarcopenic obesity (summary adjusted HR 2.01,95%CI:1.55-2.61).Nevertheless,studies on both palliative and curative surgeries were included in this meta-analysis.Some studies also included pathologies other than pancreatic cancer.

The vicious cycle of sarcopenia and chemotherapy

Most of the available studies on chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer reported a poorer response and worse survival in sarcopenic patients[49,50].In the study by Dalalet al[9],patients with inoperable locally advanced pancreatic cancer received bevacizumab in combination with capecitabine and radiation.An increased loss in skeletal muscle index of more than 3.8% was found to be associated with poorer survival (P= 0.02).The effect on survival was especially obvious in sarcopenic obesity.Pretreatment sarcopenic obesity was significantly associated with overall survival (P= 0.04) in the study by Cooperet al[51].Patients with sarcopenia or obesity alone also had a shorter median survival,but the difference did not reach statistical significance.In the retrospective study by Kayset al[49],six out of 53 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with FOLFIRINOX were found to have sarcopenic obesity.This group of patients had a significantly shorter median overall survival when compared with the rest of the cohort (10.4 movs16.1 mo;P= 0.04).

Table 2 Summary of long-term survival outcomes in sarcopenic patients in eight studies

It has been well reported that chemotherapy for other cancers affects the body composition throughout the treatment course[52-54].It was estimated that patients undergoing chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer experienced a relative muscle loss of 2.9% every 100 d (95%CI:-5.2--0.8;P= 0.01)[55].This rate of muscle loss is much greater than that in a healthy adult,who generally loses muscle at a rate of 1%-1.4% per year[56,57].The muscle-loss effect is especially prominent in the case of neoadjuvant chemotherapy.It was reported that the relative mean difference in loss of muscle mass was 4.5% more in patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy than in those having palliative chemotherapy[55].From this,one may postulate that the effect of muscle loss is not from disease progress alone,but from the chemotherapy as well.

Not only does chemotherapy potentiate sarcopenia,sarcopenia also increases the toxicity of chemotherapy[58,59].This is likely due to the fact that the dosage of chemotherapy is largely dependent on the patient's height and weight (i.e.body surface area),with the change in body composition factored out[60-62].Patients with sarcopenia tend to receive a higher dose of chemotherapeutic agent for a relatively small lean muscle mass and are thus more likely to suffer toxicity.Such a relationship is not limited to a specific tumor type or chemotherapy.In a phase 1 trial by Cousinet al[63],a low skeletal muscle index was the only factor associated with dose-limiting toxicity,regardless of cancer type.With a higher incidence of toxicity,there is also a higher incidence of treatment termination and hospitalization.This implies that the current method of dosage calculation still has room for improvement.The optimal way of adjustment for sarcopenia when prescribing chemotherapeutic agents is still an area for further research.

DISCUSSION

Assessment of nutritional status of cancer patients has evolved from a simple“eyeballing test” at bedside to sophisticated tests,such as bioelectrical impedance analysis and lean muscle mass calculation from various imaging studies.In order to identify patients with sarcopenia and provide timely intervention,a more proactive approach should be employed.Proper assessment of sarcopenia should be incorporated into the management of pancreatic cancer.Ideally,all patients receiving imaging studies can be screened for sarcopenia,but this requires special software and trained personnel.Even without those sophisticated measures,measurements from simple tests,such as hand grip strength,gait speed and bioelectrical impedance,can be obtained relatively easily in clinical settings.

In spite of all the knowledge of sarcopenia and its relationship with oncology,there is still no optimal treatment to reverse sarcopenia.On the one hand,cancer patients need adequate amounts of protein intake for anabolism,but on the other hand,excessive energy intake may potentiate obesity[64].Sarcopenic obesity has been shown to have a more deleterious effect on outcomes.The endocrine activity of visceral adipose tissue may work synergistically with cancer hormone-like mechanisms and protein wasting[65].Therefore,a careful balance of nutrition intake is crucial in the management of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity.

In additional to nutritional modification,exercise intervention is also beneficial in reversing sarcopenia.Resistance training intervention and compound exercise intervention (a blend of aerobic,resistance,flexibility and balance training) have been shown to improve muscle mass and/or physical performance[11].However,these training programs were mainly conducted in community-dwelling elderly people.They would be challenging for cancer patients due to various reasons,including fatigue and cancer-related pain.

With a better understanding of sarcopenia,clinical strategies should be revolutionized to identify and combat the condition once a patient is diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.Screening for sarcopenia in this group of patients should be made a routine practice.They should be referred to respective allied health professionals for early optimization,with reassessment at regular intervals if surgery is pending.A dedicated multidisciplinary team consisting of surgeons,oncologists,nurses,dietitians and physiotherapists will be needed.

To conclude,sarcopenia is prevalent in pancreatic cancer patients and is associated with worse survival outcomes after surgical resection and chemotherapy.In particular,sarcopenic obesity has higher morbidity and mortality risks,including the risk of POPF.The relationship between sarcopenia and other short-term surgical outcomes still remain unclear,as different studies used different cut-off values and diagnostic methods.With the latest guidelines and consensus,it is hoped that more standardized reporting can be used in upcoming studies so that good quality level 1 studies can be conducted.

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology2019年7期

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology2019年7期

- World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology的其它文章

- Recent progress of chemotherapy and biomarkers for gastroesophageal cancer

- TYMS/KRAS/BRAF molecular profiling predicts survival following adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer

- lntraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy increases the incidence of anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of rectal tumors

- Utilizing gastric cancer organoids to assess tumor biology and personalize medicine