Distant metastasis in choroidal melanoma with spontaneous corneal perforation and intratumoral calcification:A case report

Tso-Wen Wang, Hung-Wei Liu, Youn-Shen Bee

Tso-Wen Wang, Youn-Shen Bee, Department of Ophthalmology, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung 813, Taiwan

Hung-Wei Liu, Department of Pathology, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung 813, Taiwan

Youn-Shen Bee, Yuh-Ing Junior College of Health Care and Management, Kaohsiung 807,Taiwan

Youn-Shen Bee, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei 114, Taiwan

Abstract

Key words: Uveal melanoma; Choroidal melanoma; Corneal perforation; Calcification;Enucleation; Liver metastasis; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in adults.Most UMs originate in the choroid (90%), followed by the ciliary body (7%), and the iris (2%)[1].According to a study of 1352 UM cases conducted by Huet al[2], the incidence of UM was 0.38 per million per year in Asians, which is significantly lower than that reported in Caucasians (6.02 per million per year)[2].Since the clinical presentation of UM varies from being asymptomatic to vision loss depending on the size and location of the tumor, it may be difficult for affected patients to detect the disease and seek early medical attention.Currently, treatments of UM include surgical excision and radiotherapy.However, distant metastasis, especially to the liver, is common in these cases and is associated with poor prognosis.Therefore,systemic surveillance initiated as soon as UM is diagnosed is important.

In the present report, we describe rare clinical presentations and management of a case of choroidal melanoma (CM).In addition, to highlight the importance of continued follow-up of patients with CM, we report the unfavorable outcome of this case with early liver metastasis.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 63-year-old Asian woman presented to our emergency department with complaint of pain and brownish discharge from her left eye for 3 d.

History of present illness

The patient had been blind in the left eye for approximately 20 years, but never sought medical attention for her eye.She denied surgical history or experiencing trauma to the eye prior to visiting our emergency department.

History of past illness

The patient had a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus which was controlled with oral hypoglycemic agents.

Physical examination

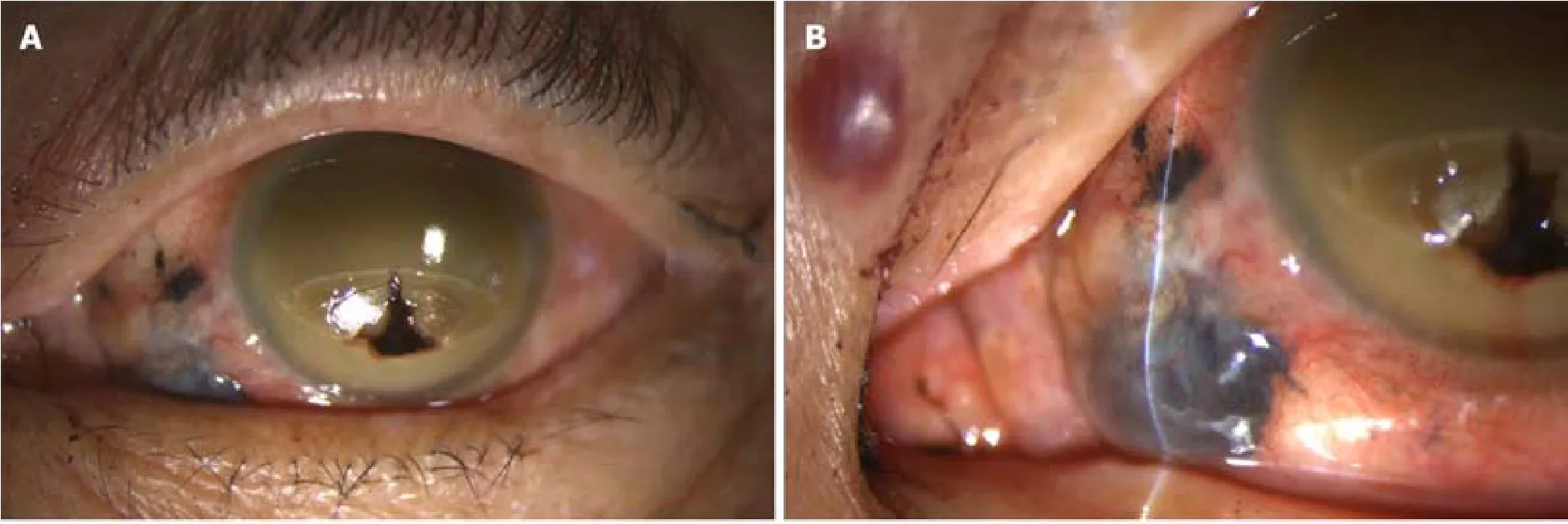

Visual acuity of no light perception was noted in the left eye.Ophthalmologic examination of the left eye revealed a 4 mm x 4 mm fixed dark brown-black subconjunctival mass with dilated and tortuous sentinel vessels at the nasal lower region.In addition, dark brown-black material with uveal tissue protruding from the perforated cornea and flattened anterior chamber was observed (Figure 1).

Laboratory examinations

Serum laboratory testing showed no abnormal results.Electrocardiogram and chest Xray were normal.

Imaging examinations

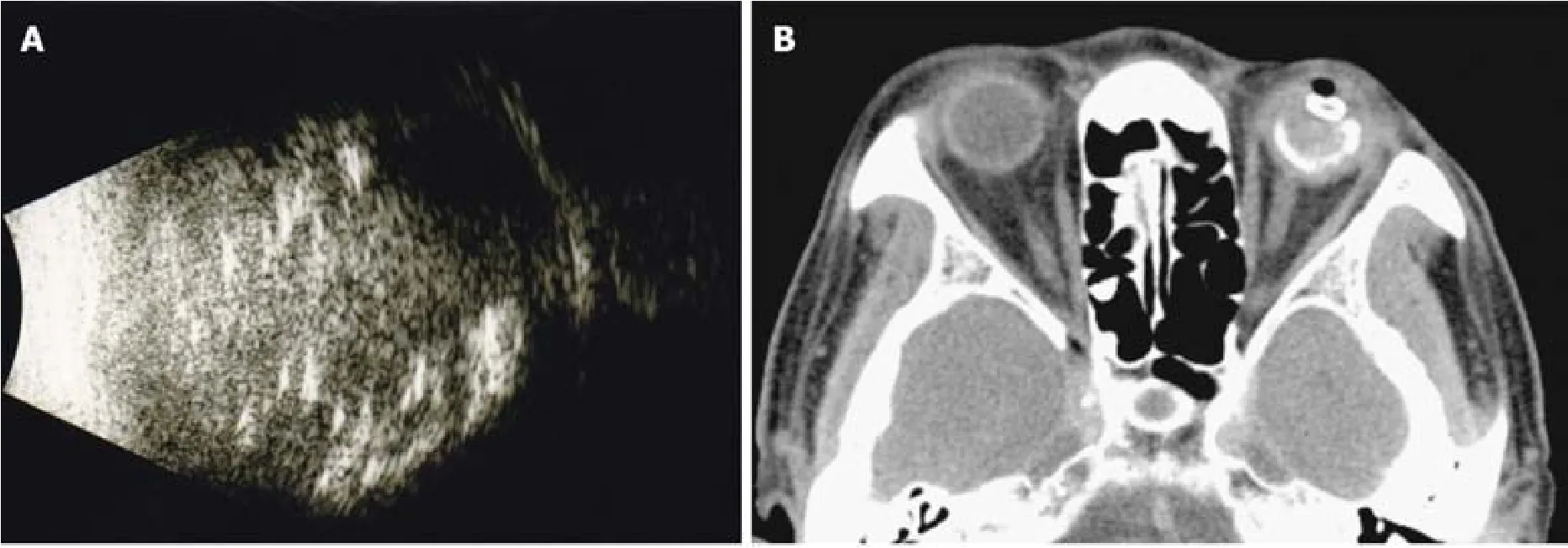

B-scan ultrasonography showed heterogeneous echogenicity throughout the left eyeball (Figure 2A).Computed tomography (CT) scan of the orbits showed a highdensity lesion in the left eye representing calcification in the vitreous cavity, choroid,and uveal tissue (Figure 2B).The lesion was confined to the left eyeball without obvious orbital extension or brain involvement.In addition, there was a gas bubble in the left eye, indicating eyeball rupture.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

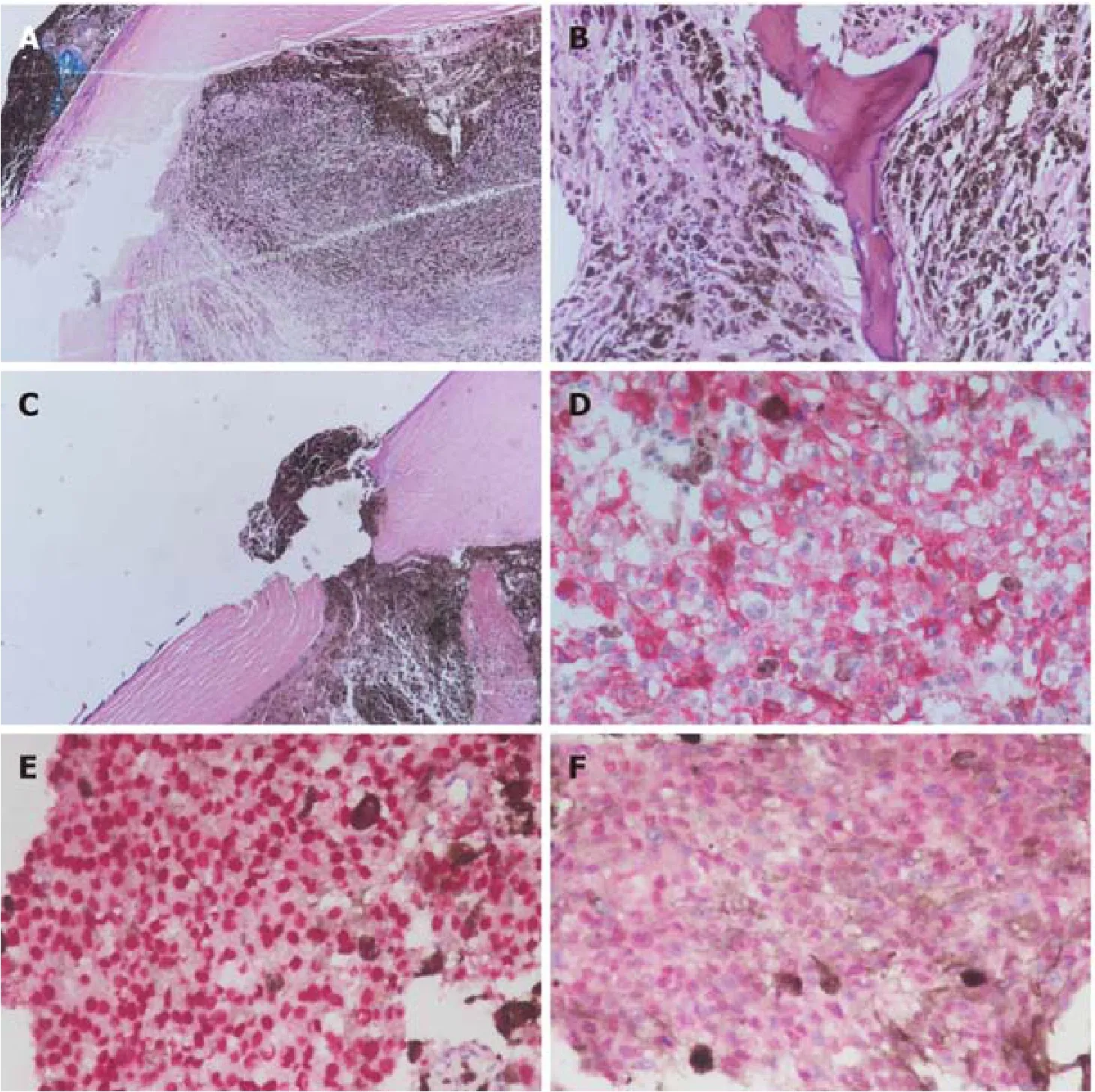

The patient underwent enucleation of the left eyeball with silicone implant (20 mm)placement and removal of pigmented conjunctival tissue on the following day.Histopathological examination revealed that the enucleated eyeball was occupied by a 17 mm × 16 mm-sized tumor.Involvement of ciliary body, iris, anterior chamber, and cornea was present.The cut end of the optic nerve was free from malignancy but an additional 4 mm x 4 mm-sized extrascleral tumor adhering to the nasal lower part of the left eyeball was found.Therefore, pT4d stage was determined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging Manual, 8thedition[3].Histological examination revealed total loss of retinal tissue with tumor adjacent to the sclera, uveal tissue in the region of the perforated cornea, and an area of fibrosiscontaining ossification in the tumor.Markedly atypical proliferation of epithelioidshaped cells was found in the tumor.The cells were heavily pigmented and contained abundant cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli.Immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed that the neoplastic cells were positive for melanin-A and Sry-related HMg-Box gene 10 (SOX-10) immunostaining with no aberrant loss of BRCA1-associated protein 1(BAP1) expression (Figure 3).Pathological diagnosis of epithelioid cell type of CM of the left eye was confirmed.

TREATMENT

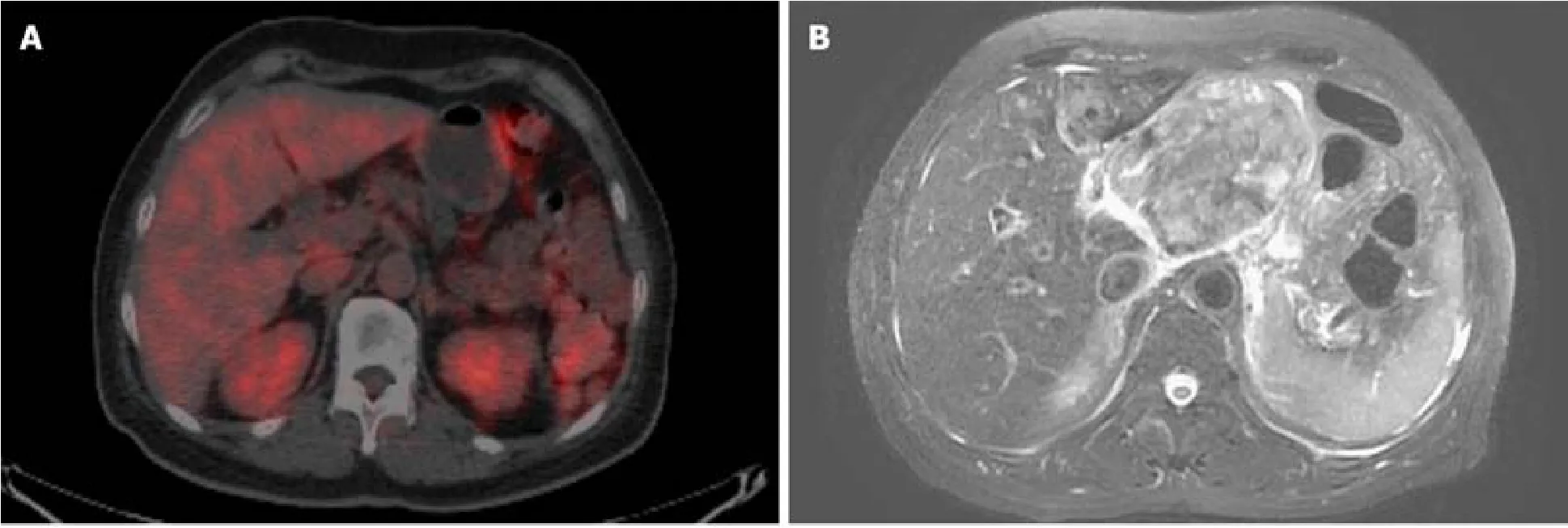

A hematology oncologist and a radiation oncologist were consulted for further systemic surveillance and treatment plan.Positron Emission Tomography-CT (PETCT) scan with F-18 Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) from head to pelvis was performed and showed FDG-avid lymph nodes in the carotid, submandibular, and posterior cervical spaces of the neck bilaterally.Since the hilum of the FDG-avid lymph nodes was intact, reactive inflammation rather than metastasis in bilateral lymph nodes in the neck was considered (N0), and no definite evidence of FDG-avid tumor was noted elsewhere (M0) (Figure 4A).Adjuvant radiation therapy was not recommended by the radiation oncologist because the surgical margin was tumor free and there was no evidence of other extraocular extension.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up 3 mo after surgery.After 1.5 years following surgery, she presented to our emergency department with complaint of dull epigastric pain that radiated to the back for 1 d and poor appetite for 2 - 3 wk.CT scan of the abdomen at a district hospital showed suspected pancreatic cancer with liver metastasis, and she was referred to our hospital for further treatment.Tests for liver function and tumor markers including alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen and CA 19-9 were within normal limits.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen showed a large mass-like lesion at the upper abdomen abutting the pancreatic neck and body with a maximal diameter of at least 9.5 cm.Several nodular lesions in the liver with left portal vein involvement were also found (Figure 4B).Endoscopic ultrasonography with fine needle aspiration was performed.Histological examination showed sheets of epithelioid and spindle neoplastic cells arranged in a solid pattern with occasional prominent nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm that exhibited stromal reaction and abundant melanin pigment.IHC showed that neoplastic cells were positive for melanin-A and SOX-10 immunostaining and no aberrant loss of BAP1 expression(Figure 5) was found.Based on both the morphology and immunophenotype, a diagnosis of metastatic melanoma with liver and pancreatic involvement was confirmed.

Figure 1 External view of the left eye.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report that discusses CM with presentation of spontaneous corneal perforation.Histopathological examination showed tumor cells protruding through the corneal perforation without invasion to adjacent cornea layers.Perryet al[4]reported a case of CM that protruded through the perforating corneal ulcer wound because of spontaneous expulsive choroidal hemorrhage.However, in our case, there was no evidence of corneal thinning, corneal ulcer, or choroidal hemorrhage.The patient denied experiencing trauma or any surgical history before presenting to our hospital.Therefore, the definite cause of spontaneous corneal perforation remained undetermined.

Intratumoral calcification is a rare presentation of CM, although it is commonly seen in retinoblastomas and choroidal osteomas.Previous case reports[5-7]indicated that destructive therapeutic interventions, such as fractional transpupillary thermotherapy or brachytherapy, might cause intratumoral calcification.Chanet al[8]and Csakanyet al[9]reported cases of CM with spontaneous calcification.The former case had calcification and the presence of osteocytes but the latter case had pure calcification.Both cases showed no evidence of tumor regression or necrosis, making the definite mechanism of spontaneous calcification unknown.In our case, however,tumor necrosis was noted.Tumor necrosis in CM is not uncommon.In a potential mechanism proposed by Tharejaet al[10], when the tumor outgrows its blood supply, it leaves a watershed area in the center and causes hypoxia and later ischemic tumor necrosis.Afterward, cytokines are released, causing tumor swelling with further necrosis.Consequently, dystrophic calcification might occur in the necrotic tissue after an extended period of time.Although currently no study has discussed the interval between tumor necrosis and calcification, we believe that there was enough time for pathological change in our patient, who had been blind for approximately 20 years but had not sought medical attention.Therefore, we report this case to highlight the possibility of calcification due to tumor necrosis in CM.

Extrascleral extension is also rare in CM.Routes of extrascleral extension previously described includeviaaqueous outflow vessels or emissary canals carrying posterior ciliary nerves, arteries, and vortex veins[11,12].However, it may be difficult for pathologists to precisely cut the eyeball specimen at the point where tumor cells exit the eye, especially when the extrascleral extension is large.In addition, a solitary metastatic tumor was noted in the orbital area but did not adhere to eyeball, creating difficulty for pathologists to differentiate these two types of tumors and determine the correct pathological stage.In the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8thedition, stage N1b was added for distinguishing cases of CM with extrascleral extension, typically adherent to the eye, with those in whom the tumor has spread regionally to the orbital area but was not contiguous with the eye with the primary tumor[3].In our case, an additional 4 mm x 4 mm-sized extrascleral tumor adhering to the lower nasal part of the left eyeball was found.Although we did not find the exiting route for the tumor cell, we highly suspected that the extrascleral extension of the tumor extendedviathe vortex vein based on its location.Therefore, the pathological stage was determined to be T4d based on the clinical evidence.

Figure 2 Initial radiological appearance of the tumor in the left eye .

It is worth mentioning that our case had an early distant metastasis (within 1.5 years of completion of enucleation).Early metastasis of CM is rare.Usually the median time to detection of distant metastasis from the diagnosis was approximate 2 to 3 years according to several previous studies[13,14].Currently, there is only a case report of early liver metastasis from CM (tumor size of 10 mm × 8.0 mm, spindle cell type, pT2cNx, within 8 mo of completion of enucleation and 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy) by Mandalet al[15]It has been shown that increasing original tumor size and stage and extraocular extension added the risk of metastasis.In the study of 8033 patients by Shieldset al[16], each increasing millimeter of thickness added approximately 5% increase in risk for metastasis at 10 years [from 6% (0-1.0 mm thickness) to 51% (> 10.0 mm thickness)].For large melanoma (> 8.0 mm), the estimated risk for metastasis at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years was 5.3%, 22.3%, 35.0%, and 49.2%, respectively.Shieldset al[17]furthermore focused on 1311 patients with large melanoma (> 10.0 mm thickness) and analyzed the estimated the risk for metastasis at 1, 3, 5, and 7 years.In the groups of > 16.0 mm thickness, which was the maximal range in all groups, the risk was 20%, 57%, 66%, and 66%, respectively.In addition,histologic factors including epithelioid type of melanoma, high mitotic activity,inflammatory infiltration, increased HLA expression, and loss of nuclear immunostaining for BAP1 protein predicted unfavorable prognosis[18,19].In the present case, epithelioid type of melanoma with a size of 17 mm × 16 mm suggested high risk of metastasis and unfavorable prognosis.

With PET-CT imaging, early detection of metastasis is possible.However, there is no test that can identify microscopic metastatic tumors, and up to 50% of patients eventually develop metastases, typically involving the liver[20].In our case, no obvious sign of metastasis was found on initial whole-body PET-CT imaging, and unfortunately the patient missed follow-up examinations that would have included physical examination, liver function tests, liver ultrasonography, and PET-CT scan or MRI of the abdomen[21].These examinations are strongly suggested for early detection of distant metastasis because prognosis is poor once metastasis occurs.One-year survival rate was reported to be 15%, and median survival varied from 4 to 15 mo[22].Current treatment options for metastatic disease included immunotherapy, such as antibodies targeting the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4, antibodies targeting the programmed cell death 1, and MEK inhibitor.However, all of the above-mentioned treatments have shown relatively low response rates.In liver metastasis, although evidence was limited, hepatic resection, regional chemotherapy such as hepatic intraarterial chemotherapy, hepatic arterial chemoembolization, and localized radioembolization using yttrium-90-labelled microspheres might improve outcome.

CONCLUSION

Figure 3 Histological findings of the resected tumor specimens.

Even though early metastasis of CM is rare[15], large tumor size increases the risk for metastasis[16].Spontaneous tumor rupture or tumor involvement outside the globe are likely to increase the likelihood of future distant metastasis.Regular follow-up with an ophthalmologist and oncologist is needed for each case.Current treatment for metastatic disease is limited and the prognosis is usually poor.Therefore, it is important for ophthalmologists to ensure that the patient receives sufficient information about the prognosis, the benefits and risks of treatment, and further follow-up plan at the time of diagnosis of CM.

Figure 4 Images from abdominal positron emission tomography-computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 5 Histological findings of the fine needle aspiration specimens.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年23期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年23期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Pure squamous cell carcinoma of the gallbladder locally invading the liver and abdominal cavity:A case report and review of the literature

- Management of massive fistula bleeding after endoscopic ultrasound-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage using hemostatic forceps:A case report

- Fatal complications in a patient with severe multi-space infections in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions:A case report

- Bouveret syndrome:A case report

- Left armpit subcutaneous metastasis of gastric cancer:A case report

- Rigid esophagoscopy combined with angle endoscopy for treatment of superior mediastinal foreign bodies penetrating into the esophagus caused by neck trauma:A case report