Cellular therapy: A promising tool in the future of colorectal surgery

Mohammed Mohammed El-Said, Sameh Hany Emile

Abstract Cellular therapy may be the solution of challenging problems in colorectal surgery such as impaired healing leading to anastomotic leakage and metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC). This review aimed to illustrate the role of cellular therapy in promotion of wound healing and management of metastatic CRC. An organized literature search for the role of cellular therapy in promotion of wound healing and management of metastatic CRC was conducted. Electronic databases including PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and Embase were queried for the search process. Two types of cellular therapy have been recognized, the mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and bone marrow-mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) therapy.These cells have been shown to accelerate and promote healing of various tissue injuries in animal and human studies. In addition, experimental studies have reported that MSCs may help suppress the progression of colon cancer in rat models. This article reviews the possible mechanisms of action and clinical utility of MSCs and BM-MNCs in promotion of healing and suppression of tumor growth in light of the published literature. Cellular therapy has a potentially important role in colorectal surgery, particularly in the promotion of wound healing and management of metastatic CRC. Future directions of cellular therapy in colorectal surgery were explored which may help stimulate futures studies on the role of cellular therapy in colorectal surgery.

Key words: Cellular therapy; Future; Colorectal surgery; Stem cells

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal surgery entails several technical aspects and various postoperative morbidities that may compromise the outcome of patients. Among these morbidities,improper healing and spread of colorectal cancer (CRC) are considered to be the most challenging problems.

Improper or delayed wound healing after reconstruction is considered a major challenge for many surgeons in the daily practice. Impaired wound healing can result in reconstruction failure which may lead to serious consequences in colorectal surgery such as anastomotic leakage (AL) and persistent fecal incontinence after failing anal sphincter repair.

It is worthy to remember that even when optimal surgical strategies and techniques are followed, failure of surgical reconstruction still occurs in a distressing rate as the case with AL after colorectal anastomosis which ranges between 1.5% and 15.9%[1,2]. It became apparent that, in addition to optimizing the surgical technique, alternative strategies may be necessary for further improvement in the healing process in order to decrease the rate of reconstruction failure.

Another serious problem is the loco-regional recurrence and distant metastasis of CRC occurring after an apparently curative surgery. Approximately 20%-25% of patients with CRC have synchronous liver metastases and another 25%-50% will develop liver metastases after apparently curative intent surgery[3]. Although the current chemotherapy has been reported to cause regression of metastatic CRC[4]with subsequent improvement in the overall survival after curative intent surgery[5], the management of patients with systemic disease is mostly palliative and metastatic cancer remains generally incurable and a major cause of cancer-related mortality.Most colorectal metastases affect the liver and only 10%-20% of them are resectable with a five-year survival rate of 30%-40%[6].

Even when radical colorectal resection is conducted, functional impairments are frequently encountered postoperatively with remarkable impact on patients' quality of life. Radical excision of rectal cancer usually results in poor bowel function,particularly low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) which affects up to 80% of patients after low anterior resection[7]. This encouraged many surgeons to adopt the"wait and watch" policy after complete clinical response of rectal cancer to neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy. Organ preservation strategies have been increasingly used for rectal cancer in the modern surgical practice.

It has been suggested that the solution of the problems aforementioned may not be in more refinement or improvement in surgical technique or chemotherapy, but in biological interventions including cellular and immunological therapies. Cellular therapy is a promising modality that may become the future of colorectal surgery.This article highlights the role of cellular therapy in promotion of healing and suppression of progression of CRC which may shed light on the potentials and future directions of this innovative therapy.

ROLR OF CELLULAR THERAPY IN TISSUE HEALING

In order to comprehend the rationale of using cellular therapy in promotion of healing, the basic concepts of cellular response to injury should be emphasized. It has been demonstrated that tissue injury stimulates the mobilization of progenitor cells from the bone marrow to the site of injury to regenerate the stroma. These progenitor cells include the fibrocytes which then differentiate into fibroblasts and deposit collagen and extracellular matrix proteins[8,9]; and the endothelial progenitor cells which form new blood vessels[10]. The end result of migration of these mononuclear cells from the bone marrow to the site of injury is the formation of granulation tissue which subsequently matures into fibrous tissue.

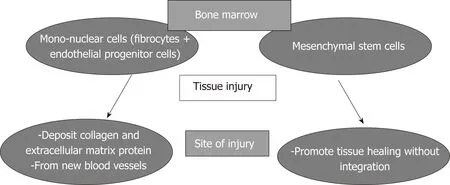

It has been shown that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) also are mobilized from the bone marrow to the site of injury to promote healing[11]without integration in the tissues[12]. Therefore, the bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) and MSCs are being mobilized in response to tissue trauma from the bone marrow to the site of injury to contribute to promotion of healing as illustrated in Figure 1. Since both have the same origin and pathway homing at the site of injury, the MSCs and BM-MNCs may belong to the same differentiation line, may have common cellular features and functions, and may have similar therapeutic efficacy[13].

The use of cellular therapy in promotion of wound healing is mainly based on the stem cell paradigm in which stem cells injected into the injured tissues will differentiate into parenchymal cells resulting in better healing and tissue regeneration.However, tissue regeneration secondary to differentiation of injected stem cells was not proved to occur in experimental studies. Another possible mechanism was postulated that stem cells may improve wound healing by secreting different healing promoting mediators, instead of differentiation into parenchymal cells[14].

On the other hand, an alternative concept, the stroma paradigm, was suggested. In this paradigm, the progenitor cells are first mobilized from the bone marrow to the site of injury to contribute to regeneration of the stroma, then the local stem cells start infiltrating the preformed stroma to regenerate the parenchyma.

In light of this paradigm, it would be logical that impaired stroma regeneration can prevent its infiltration by local parenchymal stem cells, resulting in healing by fibrosis rather than by regeneration. Many experimental studies supported the stroma paradigm against the stem cell paradigm. Three experimental studies examined the effect of local injection of stem cells on healing of injured anal sphincters[14-16]and concluded that the injected stem cells do not differentiate into skeletal muscles, yet they accelerate a normal regenerative mechanism that begins by regeneration of the stroma which is then infiltrated by muscle fibers from the nearby muscles[17].

Based on previous arguments; the use of MSCs may be not ideal in promoting healing and the BM-MNCs may be a more suitable alternative. This fraction of bone marrow contains the cells responsible for stroma regeneration ready to act, the fibrocytes and endothelial progenitor cells, in contrast to the MSCs which are supposed to be less differentiated[18,19].

Experimental and clinical studies have shown that both MSCs and BM-MNCs are equally effective in promotion of healing. Mazzanti et al[20]showed that local injection of MSCs and BM-MNCs have the same therapeutic efficacy in promotion of healing of injured anal sphincter muscles in rats. Other investigators have also reported that MSCs and BM-MNCs are equally effective in inducing regenerative changes in animal models of myocardial infarction and osteoarthritis[13,21].

Being equally effective with the MSCs, the BM-MNCs have the advantages of being less costly, easier to prepare, and not requiring weeks of in-vitro culture rendering them more suitable for clinical use[22]. The preparation of BM-MNCs takes approximately one hour after withdrawal of bone marrow. Orthopedic surgeons[22-24]have used bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) which is composed mainly of BM-MNCs[25]instead of ex-vivo cultivated stem cells in the treatment of bone defects,bone healing disorders, and osteonecrosis with promising results. Our group has also used BMAC to augment healing of repaired external anal sphincter in humans with promising results[26].

ROLE OF CELLULAR THERAPY IN TREATMENT OF METASTAIC CRC

Many studies demonstrated that MSCs home into various tumors as breast cancer,prostate cancer[27]and colon cancer[28]. It has been assumed that tumors tend to behave biologically as a wound that never heals, releasing several inflammatory mediators that recruit MSCs[29].

The effect of MSCs on tumor growth is controversial as some studies reported that MSCs can either enhance[30,31]or inhibit tumor growth[32,33]. Waterman et al[34]documented that MSCs can be primed by stimulation of toll like receptor 3 or 4 (TLR3 or TLR4) into immunosuppressive or proinflammatory MSCs, respectively. While the non-primed and immunosuppressive MSCs tend to enhance tumor growth, the proinflammatory MSCs tend to inhibit it. This concept may shed light on the controversial role and dual action of MSCs in tumor biology.

The key in using MSCs in inhibition of tumor growth lays in shifting the polarization of these cells from the immunosuppressive phenotype, which helps formation of tumor stroma (pro-tumor), to the proinflammatory phenotype which stimulates the immune system to destroy the tumor (anti-tumor). One of the strategies used for shifting polarization of MSCs to the proinflammatory phenotype is local injection of bacteria into the tumor.

Figure 1 Mobilization of mono-nuclear cells and mesenchymal stem cells from the bone marrow to the site of tissue injury.

Coley[35]treated patients with inoperable soft tissue sarcomas by local injection of heat killed bacteria "Coley's toxin" with long term disease free survival of about 50%which is considered extraordinary. Although Coley's toxin is not used now in clinical practice, intra-vesical Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) is considered the standard of care in patients with superficial bladder cancer[36]. In general, the antitumor effect of BCG on superficial bladder cancer is due to activation of the patient's immune response against the tumor[37]as evidenced by infiltration of the bladder wall by immune cells after BCG therapy[38]. To be effective, BCG therapy requires a competent host immune system[39]. We speculate that these bacterial products may prime MSCs that infiltrate the tumor to become proinflammatory, resulting to tumor regression.Although certain evidence is still lacking, combining MSCs with bacteria may help priming the MSCs to become proinflammatory which makes them a strong weapon against cancer.

Former experimental studies have documented the inhibitory effect of MSCs therapy on the progression of CRC. Francois et al[40]showed that intravenous injection of MSCs attenuated both initiation and progression of CRC in an immunocompetent rat model of colon cancer. In line with the previous study, Tang et al[41]showed that intravenous MSCs helped suppress the development of colon cancer in a colitis rat model. El-Khadragy el al[42]also showed that intra-rectal injection of non-manipulated bone marrow cells suppressed the progression of colon cancer in a rat model.

Similar to MSCs, fibrocytes seem also to either promote or suppress tumor growth through differentiation into different phenotypes. Fibrocytes that express CD34+were suggested to help inhibition of tumor growth in different cancers[43]. On the other hand, loss of CD34+on fibrocytes in tumor stroma with increased α-smooth muscle actin+are associated with increased invasive behavior of different tumors[44,45]. This may be explained by loss of the antigen presenting function of fibrocytes that lack CD34+expression, eventually leading to impaired immune response to malignant cells[40]. This concept of polarization of fibrocytes and the effect of this polarization on tumor biology is so similar to that of MSCs which may suggest common origin and functions of both cell types.

Although fibrocyte-based cellular therapies were not used yet to treat tumors even experimentally, the biologic similarity between fibrocytes and MSCs as aforementioned makes us postulate that local injection of BM-MNCs may have similar effects on tumor growth as MSCs. Perhaps the addition of a bacterial product such as BCG to either MSCs or BM-MSCs may help polarize stem cells or fibrocytes to the tumor suppressing phenotype, however, thorough and extensive research on this hypothesis is needed to ascertain its validity.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, cellular therapy may be the future solution for difficult surgical problems such as impaired healing and tumors. Cells can be locally injected at sites of reconstruction to augment healing as to prevent AL. The use of MSCs and potentially BM-MNCs may help suppress the progression of metastatic CRC without the morbidity, mortality and limitations of major surgery. Further animal studies are highly required to prove the validity of these concepts.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年13期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年13期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Systematic review with meta-analysis on transplantation for alcoholrelated liver disease: Very low evidence of improved outcomes

- Efficacy and complications of argon plasma coagulation for hemorrhagic chronic radiation proctitis

- Performance of tacrolimus in hospitalized patients with steroidrefractory acute severe ulcerative colitis

- Comparison of Hemospray® and Endoclot™ for the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding

- Plasma microRNAs as potential new biomarkers for early detection of early gastric cancer

- Characterization of hepatitis B virus X gene quasispecies complexity in mono-infection and hepatitis delta virus superinfection