Predicting surgical site infections using a novel nomogram in patients with hepatocelluar carcinoma undergoing hepatectomy

Tian-Yu Tang, Yi Zong, Yi-Nan Shen, Cheng-Xiang Guo, Xiao-Zhen Zhang, Xiu-Wen Zou, Wei-Yun Yao,Ting-Bo Liang, Xue-Li Bai

Abstract

Key words: Surgical site infection; Nomogram; Hepatectomy; Risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Over the last few decades, with the advances in operative techniques and intensive perioperative management, the perioperative mortality rate after hepatectomy has been markedly reduced[1,2].However, the relatively high morbidity rate among these cases is still a problem.Nosocomial infections remain a major cause of morbidity among patients undergoing liver resection, and surgical site infections (SSI)reportedly account for > 50% of infectious complications after surgery[3-7].In particular, in patients undergoing hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),SSI have a significant impact on morbidity, mortality, prolonged hospitalization,costs, and long-term oncology outcomes[8].Hence, SSI prevention has been considered a top priority for improving perioperative outcomes.Previous studies suggest that many factors can influence SSIs in patients undergoing hepatectomy, including age,overweight status, liver function, hepatolithiasis, hypoalbuminemia, anemia, diabetes,repeat hepatectomy, operating time, intraoperative blood loss and transfusion,postoperative bile leakage, and prolonged drainage[3,5,7,9-14].However, some of these factors remain controversial.

To identify patients with an increased risk of SSI and improve their perioperative outcomes, several prediction models have been developed, such as the Nosocomial Infection Control index and the National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance (NNIS)risk index proposed by Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC)[15,16].However, these models have been developed using data from a wide range of patients undergoing various surgical procedures with different disease conditions.Hence, the applicability of these prediction models is limited in patients undergoing hepatectomy for HCC, whose conditions are usually worse as compared to patients undergoing other surgical procedures.The identification of actual risk factors for SSI after hepatectomy for HCC and development of effective forecasting models to screen out patients at high risk of SSI are vital for improving individual clinical decision making and the perioperative morbidity rate.

A nomogram is a convenient and widely applicable tool for surgeons to predict the risk of adverse events and prognosis of patients.Several prediction models have been developed to predict the survival rates and postoperative complications of patients undergoing hepatectomy[17-19].However, only few studies have focused on developing prediction models for SSI.In the present study, we aimed to investigate the risk factors for SSI after hepatectomy for HCC, and develop a prediction model for SSI by analyzing clinical data from a consecutive series of patients undergoing hepatectomy at our institution and validate the prediction model in an external cohort.

METERIALS AND METHODS

Patient cohort and data collection

The data of 640 patients with HCC who underwent attempted curative liver resection were retrospectively collected from two academic institutions in China.Patients from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine were used as the training cohort (n= 309), whereas patients from Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital were used as the validation cohort (n= 331).These two institutions are highvolume centers for liver cancer surgery.Only patients who underwent hepatectomy(R0 or R1 resection) and had histopathologically confirmed HCC according to the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) criteria were included[20].The inclusion criteria were:(1) Age between 18 and 85 years; (2) Patients with resectable HCC scheduled to undergo hepatectomy; and (3) Liver function classified as Child-Pugh A or B.Patients who underwent hepatectomy with biliary reconstruction or concomitant organ resection, such as colorectal resection, were excluded.This study was approved by the ethics committees of all involved hospitals.Written informed consent was obtained from patients for the use of their clinical data for research.

Patient management

The records of all patients were reviewed preoperatively by experienced surgeons and radiologists to determine whether the planned procedures were appropriate based on the extent of progression, liver function, and general condition of the patients.Resectability and disease progression were preoperatively evaluated according to the imaging studies.Liver function was assessed using liver biochemistry tests, the Child-Pugh grade, and the indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min.Anatomic hepatectomy was performed whenever possible, and partial hepatectomy was conducted in patients with limited liver reserve and tumor at a specific location.Prophylactic antibiotics (a first-generation cephalosporin) were administered 30 min before skin incision, every 3 h during the surgery, and twice daily for 2 d after the surgery, according to the CDC guidelines.Drains were routinely placed in the right subphrenic space, foramen of Winslow, or along the cut surface of the liver, based on the type of hepatectomy, and were connected to a closed drainage system.Tubes were routinely removed when there were no signs of bile leakage,hemorrhage, or infection on postoperative day 3 or 4.

Data collection and outcomes definition

The reviewed data of patients undergoing hepatectomy included gender, age, body mass index (BMI), activities of daily living (ADL), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, history of smoking and alcohol abuse,etiology, comorbidity, hepatitis, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, Child-Pugh classification, laboratory test, repeat hepatectomy, and surgical information.SSI were diagnosed according to the criteria of the NNIS[21].For the assessment of SSI, all postoperative data of the patients relevant to SSI were reviewed (e.g., fever,postoperative radiologic examination, laboratory tests, characteristics of drainage fluid, culture of fluid and tissue from the surgical site, interventional radiologic procedures, reoperation, and organ failure).Perioperative death was defined as death of patients within 30 days after surgery.The Clavien-Dindo classification was used to assess the severity of SSIs.The ASA score was determined by experienced anesthesiologists before surgery[22].The NNIS risk index was calculated based on the following criteria:ASA > 2, wound class (contaminated, dirty, or infected), and operation duration above the 75thpercentile, wherein each present risk factor added 1 point to the total score[16].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as median and interquartile range, whereas categorical variables are expressed as frequency and proportion.The risk factors for SSI were identified using univariate and multivariate analyses with SPSS 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).The categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate.Continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-WhitneyUtest, whereas logistic regression analysis was performed for multivariate analysis; for these analyses, odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.A nomogram was formulated based on the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis, using the rms package in R, version 3.2.1 (http://www.r-project.org/).Points are added across independent variables according to the nomogram to derive the total points, which are converted to predicted probabilities.The performance of the nomogram was measured using the concordance index (C-index), and was assessed in the validation cohort against that in the training cohort.AP-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

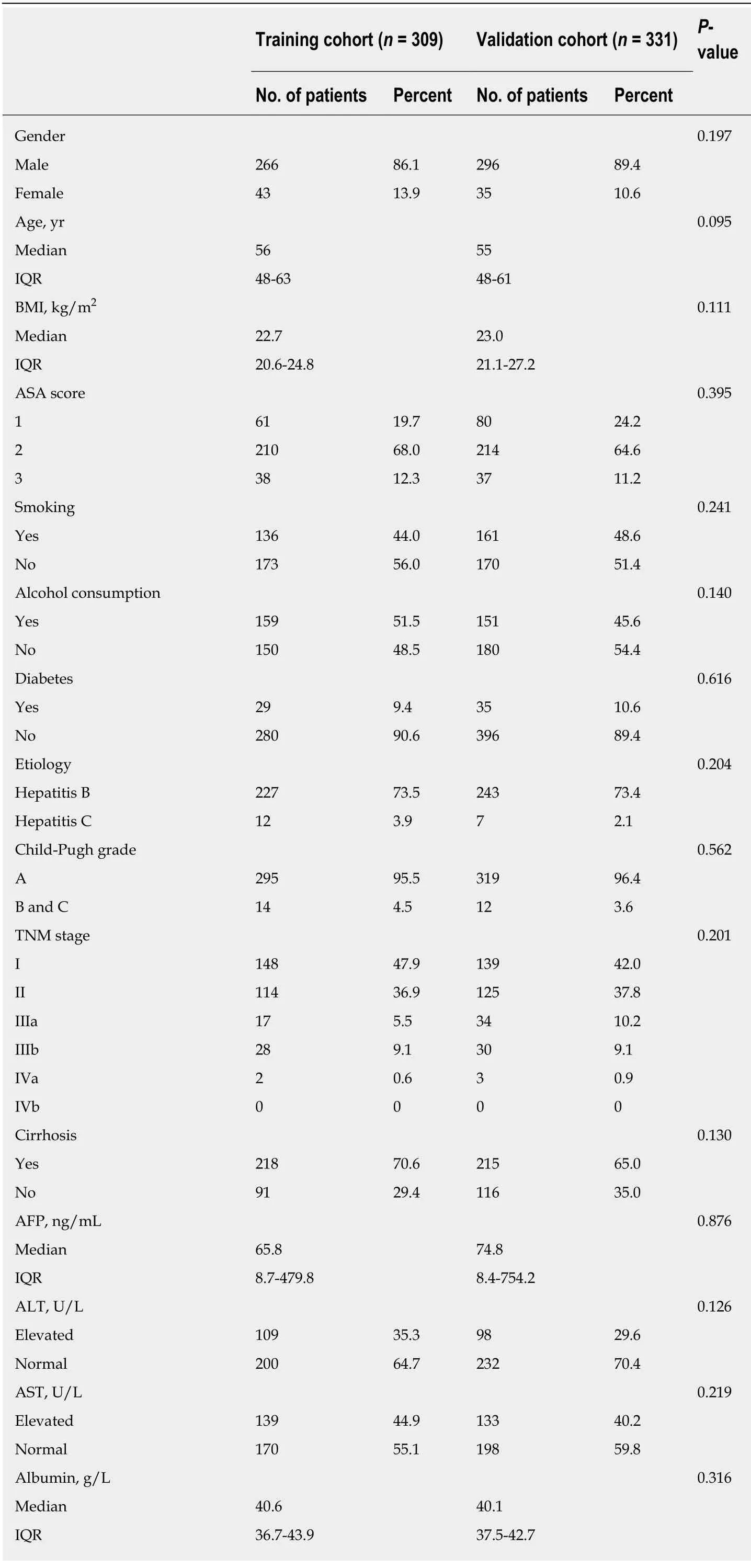

A total of 640 patients met the enrollment criteria and were included in the study(mean age, 54.9 years; 87.8% of males); all the patients underwent hepatectomy for HCC.The patients from the first institution were used as the training cohort (n= 301)and those from the second institution were used as the validation cohort (n= 331).No significant differences were observed in the baseline characteristics of the patients between the two cohorts (Table 1).Among all the patients, the incidence rates of overall, incisional, and organ/space SSI in the training cohort were 10.6% (n= 33),7.4% (n= 23), and 5.2% (n= 16), respectively.The incidence rates of overall, incisional,and organ/space SSI in the validation cohort were 11.4% (n= 37), 7.1% (n= 26), and 4.2% (n= 14), respectively.The mean postoperative stay duration was 9.58 (range,3–45) and 9.76 (range, 3–56) days in the training and validation cohorts, respectively.The 30-d mortality rate was 0.7% in the training cohort, with 1 death due to sepsis and 1 death due to liver failure, whereas the 30-d mortality rate was 0.6% in the validation cohort, with 1 death due to postoperative hemorrhage and 1 death due to intraabdominal infection.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for overall SSI

The pre-operative and intra-operative variables in the training cohort were evaluated using univariate analysis and logistic regression to identify the factors associated with SSI.In particular, six variables were found to be significantly associated with the occurrence of SSI on univariate analysis, including ASA score, major resection,intraoperative blood loss, duration of operation, repeat hepatectomy, and serum albumin level (Table 2).Thereafter, logistic regression identified three pre-operative variables (serum albumin level, repeat hepatectomy, and ASA score) and one intraoperative variable (duration of operation) as independent predictors of overall SSI(Table 2).

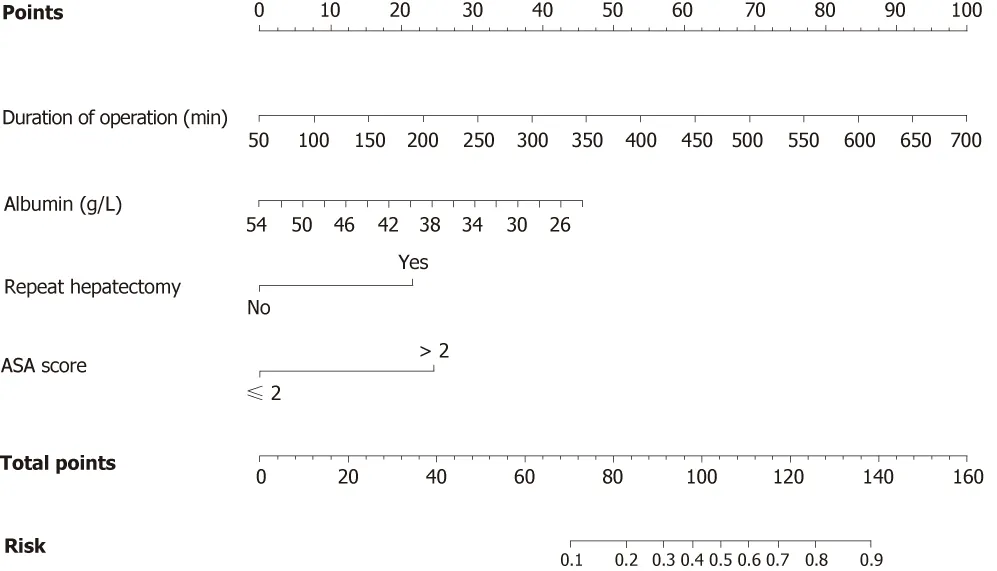

Development and validation of a predictive nomogram

We developed a nomogram to predict SSI in patients after hepatectomy for HCC by integrating the four factors identified during the multivariate analysis (Figure 1).Each factor was assigned a weighted number of points.The total number of points for each patient was calculated using the nomogram, and was associated with an estimated probability for SSI.For example, a patient with 46 g/L serum albumin (12.5 points)and ASA physical status classified as 2 (0 point) underwent a 3-hour surgery (19.8 points), including initial resection for HCC (0 point).The total score for this patient was 32.3, indicating a 4.6% probability of developing SSI.

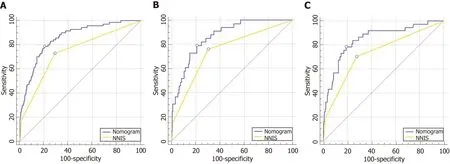

The C-index of the nomogram for predicting SSI was 0.86 for the training cohort and 0.84 for the validation cohort (Figure 2A and 2C).Moreover, the calibration curve indicated adequate consistency between predictions using the nomogram and the actual observed outcome in both cohorts (Figure 2B and 2D).

We compared the nomogram with the NNIS risk index in both the training and validation cohorts, and our nomogram showed better prediction accuracy (Figure 3).

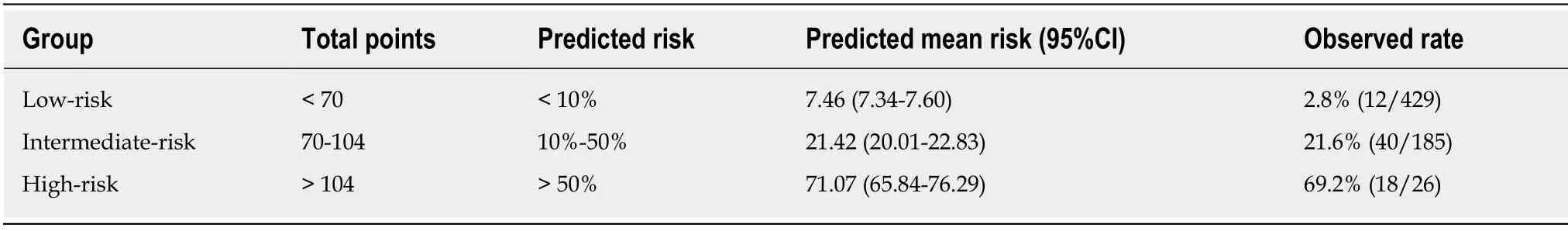

Risk groups based on the nomogram

We stratified the patients of the entire cohort into three groups with a distinct risk of SSI, based on the predicted risk distribution using the nomogram.The predicted mean risk of the low-risk group was 7.46% (total points < 70; predicted rate, < 10%), of the intermediate-risk group was 21.42% (total points, 70–104; predicted rate,10%–50%), and of the high-risk group was 71.07% (total points > 104; predicted rate, >50%).The observed incidences of SSI differed significantly between the three groups,and were close to the predicted SSI rate (Table 3).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the cohorts

BMI:Body mass index; ADL:Activities of daily living; AFP:Alpha-protein; TB:Total bilirubin; INR:International normalized ratio; Hb:Hemoglobin; PLT:Platelets; SSI:Surgical site infection; RFA:Radiofrequency ablation; TACE:Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

DISCUSSION

SSI have been defined as infections associated with surgical procedures.According to data published by the CDC and Healthcare Infection Control Practices AdvisoryCommittee (HICPAC) in 2017, the incidence of SSI after bile duct, liver, and pancreatic operations was 3.6%[23].In previous reports, the SSI rate after hepatectomy ranged from 2.1% to 14.5%[4,7,10,24].Although it might be impossible to completely reduce the SSI rate to 0%, surgeons currently foster an environment with zero tolerance to SSI.Nevertheless, the reduction of the SSI rate after hepatectomy remains a major challenge.

Table 2 Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for surgical site infections in the training cohort

In the present study, we aimed to establish a forecasting model that could identify patients with an increased risk of SSI immediately after surgery, thus offering surgeons the opportunity to reduce the SSI rate by modifying the treatment in advance.To our knowledge, this is the first study to develop a nomogram for predicting SSI in patients undergoing hepatectomy for HCC.Furthermore, the nomogram was verified using an external cohort to assess the reliability and practicability of the forecasting model.Here, we discuss the following four risk factors for SSI identified in the present study:Serum albumin level, repeat hepatectomy, ASA score, and duration of operation.

We found that patients who underwent repeat hepatectomy were more likely to develop SSIs, consistent with previous studies[25-28].One explanation for this finding is that, to ensure minimum trauma for patients, the original incision site was usually considered as the optimal operation approach for repeat hepatectomy.This may lead to delayed wound healing and increased risk for SSI due to the presence of scar tissue,which may also be associated with hypo-perfusion of the surgical site.Scar removal may help increase perfusion of the surgical wound; however, this approach may lead to higher tension at the surgical site, which may also contribute to poor wound healing.In addition, this finding may be related to the higher bile leak rate in patients undergoing repeat hepatectomy.Sadamoriet al[6]reported that repeat hepatectomy was an independent risk factor for bile leak and SSI after surgery[6].The damage and latent stricture of the hepatic duct induced by radiofrequency ablation (RFA), transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), or initial surgery may be the main cause of increased bile leak rate and SSI rate in patients undergoing repeat hepatectomy.We only included pre- and intra-operative predictors in our study to establish an advanced prediction model, thus aiming to provide surgeons with opportunities to reduce the SSI rate.However, given the significant association between SSI and postoperative factors such as bile leakage, ascites, and prolonged drainage, we believe that surgeons should be alert to the increased risk of SSI in certain patients in clinical practice, especially those who develop bile leakage regardless of whether they have a relatively low nomogram score.

Figure 1 Nomogram predicting the probability of surgical site infection occurrence in patients undergoing hepatectomy.

Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is frequently observed in patients undergoing hepatectomy.Several studies have suggested that hypoalbuminemia has a great predictive value for the mortality and morbidity rates in this population[5,13,25].As a marker of malnutrition and liver dysfunction, hypoalbuminemia was the only laboratory value identified as an independent risk factor for SSI in our study.This finding may be related to impaired tissue healing caused by decreased collagen synthesis and granulation tissue formation at the surgical site[29,30].Another possible explanation could be that hypoalbuminemia may cause tissue edema, which could subsequently lead to hypo-perfusion of the surgical site.Furthermore, fluid collection at the surgical site due to decreased serum osmolality provides a medium for bacterial propagation[31].Moskovitzet al[32]reported that the use of specialized enteral diets enriched with specific immunonutrients can improve the perioperative outcomes of malnourished patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery.Thus, we believe that hypoalbuminemia patients may benefit from additional nutrition support and more intensive perioperative care.

We observed that a high ASA score and prolonged surgery were significantly associated with the occurrence of SSI, in line with previous studies[5,6,13].Moreover,these two predictors have been found to be associated with postoperative complications in a wide range of patients with different disease conditions.Patients with a higher ASA score were more likely to have concomitant diseases and a worse performance status.Prolonged surgery reflects a more complicated surgical procedure and increased surgeon fatigue, which could lead to additional technical errors.In cases with a prolonged operating time, the incision and tissue are exposed to the environment for a longer duration, which could contribute to an increased risk of bacterial contamination.In fact, the experience of the surgical team plays an important role in determining the duration of surgery.In the present study, all procedures were performed by experienced surgeons with well-trained support staff at high-volume centers.However, due to the varying conditions of different surgical teams, the magnitude of this association may change in different centers.

The four factors finally included in the nomogram are easily available, and the predicted probability of SSI can be calculated immediately after surgery through this method.Moreover, we categorized patients into three groups based on their distinct risk of developing an SSI to better guide clinical practice.For patients in the intermediate- and high-risk groups, we suggest that intensive monitoring of the patient’s condition after surgery should be implemented, and prolonged postoperative antibiotic administration and upgraded antibiotic agents should be considered.

Figure 2 Receiver operating characteristic curve of nomogram prediction in the training cohort (AUC = 0.86) (A) and in the training cohort (AUC = 0.84) (B)Calibration curve of nomogram prediction in the training cohort (C) and validation cohort (D).

In the present study, the area under the ROC curve for the nomogram was significantly higher than that for the NNIS risk index (0.85vs0.75 for the whole population).Our nomogram appears to indicate a higher accuracy for predicting SSI,as compared to the NNIS risk index.One reason for this finding is that the NNIS risk index stratifies the SSI risk using three equally weighted factors:ASA > 2, wound class, and operation duration.However, the wound classification does not apply in our population as all the surgeries included in our study were clean.In addition, our prediction model integrated the information of hepatic surgery history and liver function, which were significantly associated with SSI in our population.Furthermore, the NNIS risk index was developed using a wide range of patients,whereas our prediction model was established only using patients who underwent hepatectomy for HCC.The increased relevance could explain the better performance of our prediction model in this population.

Nevertheless, the present study has certain limitations.First, the possibility of selection bias should be considered because of the retrospective nature of our study.The rate of major hepatectomy was relatively low, which could have contributed to the low SSI and mortality in our cohorts.Some of the intraoperative parameters such as body temperature, administration of inspired oxygen, and exact volume replacement during the surgery were difficult to obtain retrospectively, even though previous studies have found that these parameters may be associated with SSI occurrence[33-35].Although most patients were managed according to the CDC guidelines, incomplete records may still lead to bias.Moreover, we included only 640 patients in our study.Although this cohort is statistically adequate for developing and validating a prediction model, it is still a relatively small cohort compared to that in other studies.Furthermore, the nomogram was developed and validated using data only from two high-volume centers in China, and the ability of this model to predict SSIs in a wider population should be tested in additional institutions.

Figure 3 Receiver operating characteristic curve of prediction with the nomogram and the NNlS risk index.

In conclusion, we have developed the first forecasting model to predict SSI in patients undergoing hepatectomy for HCC.This nomogram is able to stratify patients into three groups with distinct risks of SSI, and performs well on external validation.However, the reliability and applicability of the nomogram need to be validated in additional centers in the future.

Table 3 Risk groups based on the predicted nomogram

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Surgical site infections (SSI) reportedly account for > 50% of infectious complications after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).It has a significant impact on morbidity,mortality, prolonged hospitalization, costs, and even long-term oncology outcomes.Hence, SSI prevention has been considered a top priority for improving perioperative outcomes.Previous studies suggest that many factors can influence SSIs in patients undergoing hepatectomy.However, some of these factors remain controversial.

Research motivation

Models to identify the patients with an increased risk of developing SSI are limited.National Nosocomial Infection surveillance (NNIS) risk index was developed using data from a wide range of patients undergoing various surgical procedures with different disease conditions.Hence, the applicability of NNIS is limited in patients undergoing hepatectomy for HCC.To develop an effective forecasting model to screen out patients at high risk of SSI is vital for improving individual clinical decision making and the perioperative morbidity rate.

Research objectives

In this study, we aimed to investigate the risk factors for SSI after hepatectomy for HCC, and develop a prediction nomogram for SSI by analyzing clinical data from a consecutive series of patients undergoing hepatectomy at our institution and validate the prediction model in an external cohort.

Research methods

The data of 640 patients with HCC who underwent attempted curative liver resection were retrospectively collected from two academic institutions in China.The records of all patients were reviewed.We identified the independent predictors of SSI using multivariate logistic regression analysis.Then, a nomogram was formulated based on the identified factors, using the rms package in R, version 3.2.1 (http://www.r-project.org/).The performance of prediction model was assessed using an external cohort from the second hospital.

Research results

The logistic regression identified three pre-operative variables (serum albumin level, repeat hepatectomy, and ASA score) and one intra-operative variable (duration of operation) as independent predictors of overall SSI.We developed a nomogram to predict SSI in patients after hepatectomy for HCC by integrating the four factors identified.Our nomogram showed better prediction accuracy compared to the NNIS risk index.Finally, we stratified the patients of the entire cohort into three groups with a distinct risk of SSI, based on the predicted risk distribution using the nomogram.

Research conclusions

Our nomogram appears to indicate a higher accuracy for predicting SSI, as compared to the NNIS risk index.Our prediction model integrated the information of hepatic surgery history and liver function, which were significantly associated with SSI in our population.The NNIS risk index was developed using a wide range of patients, whereas our prediction model was established only using patients who underwent hepatectomy for HCC.The increased relevance could explain the better performance of our prediction model in this population.

Research perspectives

This nomogram based on identified factors is able to stratify patients into three groups with distinct risks of SSI, and performs well on external validation.We primarily focused on the preoperative and intra-operative predictors because we aimed to develop a prediction model to identify suitable patients for enhanced recovery after surgery at a relatively early time point.In the future, we will assess the performance of this model among a diverse population of patients.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年16期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年16期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Role of infrapatellar fat pad in pathological process of knee osteoarthritis:Future applications in treatment

- Application of Newcastle disease virus in the treatment of colorectal cancer

- Reduced microRNA-451 expression in eutopic endometrium contributes to the pathogenesis of endometriosis

- Application of self-care based on full-course individualized health education in patients with chronic heart failure and its influencing factors

- Serological investigation of lgG and lgE antibodies against food antigens in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

- lncidence of infectious complications is associated with a high mortality in patients with hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure