Short- and long-term outcomes of endoscopically treated superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumors

Yuko Hara, Kenichi Goda, Akira Dobashi, Tomohiko Richard Ohya, Masayuki Kato, Kazuki Sumiyama,Takehiro Mitsuishi, Shinichi Hirooka, Masahiro Ikegami, Hisao Tajiri

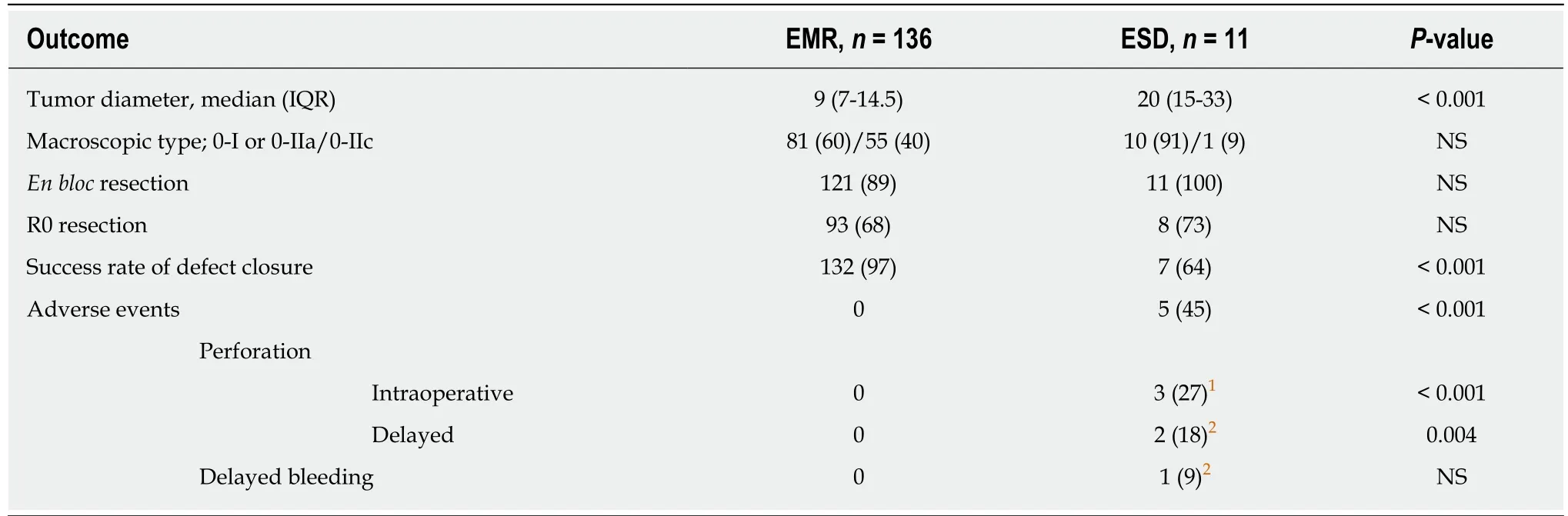

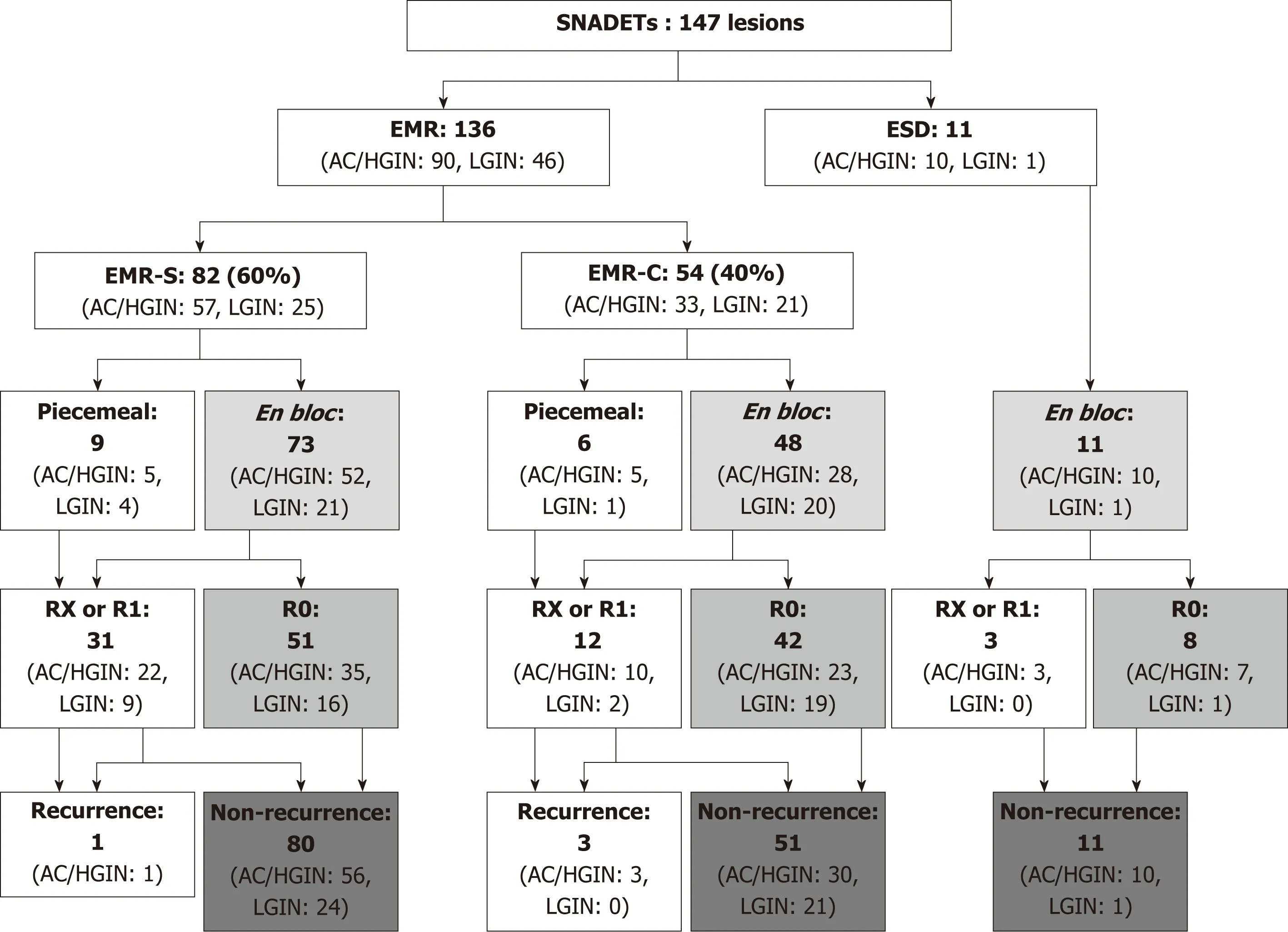

Abstract BACKGROUND It is widely recognized that endoscopic resection (ER) of superficial nonampullary duodenal epithelial tumors (SNADETs) is technically challenging and may carry high risks of intraoperative and delayed bleeding and perforation.These adverse events could be more critical than those occurring in other levels of the gastrointestinal tract. Because of the low prevalence of the disease and the high risks of severe adverse events, the curability including short- and long-term outcomes have not been standardized yet.AIM To investigate the curability including short- and long-term outcomes of ER for SNADETs in a large case series.METHODS This retrospective study included cases that underwent ER for SNADETs at our university hospital between March 2004 and July 2017. Short-term outcomes of ER were measured based on en bloc and R0 resection rates as well as adverse events. Long-term outcomes included local recurrence detected on endoscopic surveillance and disease-specific mortality in patients followed up for ≥ 12 mo after ER.RESULTS In the study, 131 patients with 147 SNADETs were analyzed. The 147 ERs consisted of 136 endoscopic mucosal resections (EMRs) (93%) and 11 endoscopic submucosal dissections (ESDs) (7%). The median tumor diameter was 10 mm.The pathology diagnosis was adenocarcinoma (56/147, 38%), high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (44/147, 30%), or low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia(47/147, 32%). The R0 resection rate was 68% (93/136) in the EMR group and 73% (8/11) in the ESD group, respectively. Cap-assisted EMR (known as EMR-C)showed a higher rate of R0 resection compared to the conventional method of EMR using a snare (78% vs 62%, P = 0.06). No adverse event was observed in the EMR group, whereas delayed bleeding, intraoperative perforation, and delayed perforation in 3, 3, and 5 patients occurred in the ESD group, respectively. One patient with perforation required emergency surgery. In the 43 mo median follow-up period, local recurrence was found in four EMR cases and all cases were treated endoscopically. No patient died due to tumor recurrence.CONCLUSION Our findings suggest that ER provides good long-term outcomes in the patients with SNADETs. EMR is likely to become the safe and reliable treatment for small SNADETs.

Key words: Duodenal adenoma; Duodenal cancer; Endoscopic resection; Endoscopic submucosal dissection; Long-term outcome

INTRODUCTION

Primary duodenal cancer is one of the gastrointestinal tumors with a low frequency of occurrence. Its prevalence rate in necropsy cases is reported to be 0.02%-0.5%[1].Precancerous lesions, duodenal adenomas, are also rare and reported in approximately 0.1%-0.4% of patients who have undergone an esophagogastroduodenoscopy[2,3]. Previous studies showed that the 5-yr survival rate of patients with duodenal cancer was less than 30%[4]. Duodenal cancer has the poorest prognosis among cancers of all parts of the small intestine because most cases are detected at a far-advanced stage[4]. Additionally, since the duodenum is adjacent to important organs, such as the pancreas, gallbladder and liver, invasion or spread to these organs will be a factor of poor prognosis. Early detection and treatment of duodenal cancer will be necessary to improve patient prognosis. It, however, remains unknown about the clinical course of those patients who have early-stage cancer and adenomas in the duodenum.

Among duodenal tumors, epithelial tumors located at the ampullary site are classified as biliary tract tumors[5]. The ampullary tumors are different from nonampullary tumors in endoscopic diagnosis and treatment. In the previous study,superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumors (SNADETs; as adenoma or mucosal/submucosal carcinoma located outside the ampullary region) are considered an indication of endoscopic resection (ER) because of a low risk of lymph node metastasis[6-8].

ER for SNADET is a challenging technique compared to other gastrointestinal tracts because of the following reasons. First, the anatomical features, a narrow lumen and precipitous curvature of the duodenum, can provide inadequate view and make it difficult to maintain stable view of the endoscope. Second, Brunner’s glands in the submucosal layer can stiffen the duodenal wall; therefore, mucosal lifting is poor at submucosal injection, making ER more difficult, especially for the macroscopically depressed type of tumors. The muscular layer of the duodenum is very thin and this increases the risk of perforation[9].

Due to the rarity of SNADETs and the difficulty of ER, there have been few largescale studies including more than 100 cases conducted to evaluate treatment outcomes of ER in patients with SNADETs. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the shortand long-term outcomes of ER with more than 100 cases of SNADET to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and curability of the endoscopic treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective study included the patients who underwent ER for SNADETs in a single-center at Jikei University Hospital between March 2004 and April 2017, and who met the following criteria: (1) newly diagnosed SNADET that included adenomas of low/high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN/HGIN) and superficial adenocarcinomas in which invasion was confined to the submucosal layer; and (2) no lymph node or distant organ metastasis. This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan,for clinical research [Registration No.: 29-079 (8695)]. This study was conducted in compliance with the revised Helsinki Declaration (1989).

Indications for ER

Indications for ER were defined as follows: (1) histologically diagnosed as adenoma with HGIN or adenocarcinoma by endoscopic biopsy; and (2) tumor lesions of macroscopic type 0-I and 0-IIa > 10 mm or type 0-IIc > 5 mm in diameter, which were endoscopically suspected as HGIN or superficial adenocarcinoma based on results of our previous study[6,10,11]. Lesions were suspected as HGIN or superficial adenocarcinoma when they showed a reddish area on white light endoscopy or an obscure mucosal pattern or network vascular pattern on magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging[6,11].

Endoscopic procedures

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was mainly performed for lesions ≥ 20 mm in diameter, and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) was performed for lesions < 20 mm in diameter. EMR was performed under conscious sedation using pethidine hydrochloride (Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and flunitrazepam(Eisai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and ESD was performed under general anesthesia.When performing EMR, 10% glycerin solution (Glycerol; Chugai Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with a minute amount of indigo carmine dye was used for submucosal injection to lift up the superficial lesion. When performing ESD, 0.4%sodium hyaluronate (MucoUp; Boston Scientific Japan Co., Tokyo, Japan) was injected into the submucosal layer to obtain adequate and sustained submucosal elevation.

Two types of EMR were performed. Basically, a conventional method of EMR was performed using a snare (EMR-S) mainly for elevated lesions, and “EMR-C” method was performed mainly for depressed-type lesions. EMR-C is an aspiration resection method using a medium-sized transparent plastic cap (MAJ-296, 16.1 mm; Olympus,Tokyo, Japan). A “suck and shake” method was used for this procedure to avoid perforation, as shown in Figure 1. If en bloc resection was not achieved in the initial resection, additional resection using the snare was performed to remove the residual portion of the lesion. Otherwise, coagulation method using either hot-biopsy forceps(Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or argon plasma coagulation (VIO300D; ERBE Elektromedizin, Tubingen, Germany) was occasionally carried out when minute tumor remained[12,13]. A dual knife and hook knife (KD-650L and KD-620LR,respectively; Olympus) were used for ESD (Figure 2). We tried to completely close or cover mucosal defects by clip closure or tissue shielding methods in all EMR and ESD cases to prevent delayed bleeding and delayed perforation[14,15].

Figure 1 The cap-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection method of superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumor. This is the “suck and shake”technique. Type 0-IIc lesion, 10 mm × 5 mm, mucosal carcinoma, cut-end negative. A: Indigo carmine spraying view. Depressed-type lesion was located in the second portion of the duodenum; B: Injecting the glycerol into submucosal layer; C: Sucking the lesion; D: Shaking the lesion to prevent muscle layer involvement; E: Ulcer findings just after lesion removal. The lesion was resected en bloc, and there was no bleeding or perforation in the ulcer just after the procedure; F: Closing the ulcer floor completely by clip to prevent delayed bleeding and perforation.

All patients were admitted to our hospital and remained nil per os for 48 h. On day 2, patients were provided with a liquid diet and patients with an unremarkable postoperative course were discharged from the hospital on day 7 after ER.

Adverse events

Delayed bleeding was defined as a postoperative decrease in hemoglobin level of >2.0 g/dL[16]. Delayed perforation was defined by the presence of free air on postoperative computed tomography (CT), with severe abdominal pain in patients without intraoperative macroscopic perforation.

Surveillance after ER

Patients underwent an initial follow-up endoscopy at 2 mo after ER. Thereafter,endoscopic surveillance was performed at 6 mo or 12 mo intervals. If a residual tumor was suspected, a biopsy was performed and the tissue obtained was examined histologically. We conducted a CT at 12 mo interval to detect metastasis in the patients with mucosal adenocarcinoma. If the pathology diagnosis was submucosal carcinoma (SMC), additional surgical local resection of duodenum was performed. If a patient was referred to another hospital after ER, a telephone survey with the referred physician was conducted to ascertain the date of the last endoscopic followup, tumor recurrence status, and survival status.

Pathology diagnosis

Pathology diagnosis was established by two expert gastrointestinal pathologists (SH,TM) who were blinded to the endoscopic finding. As aforementioned, SNADETs were histologically defined as adenoma and superficial adenocarcinoma consisting of mucosal carcinoma (MC) and SMC. The grade of atypia of all tumors was estimated in the highest atypical region and was categorized according to the World Health Organization (commonly known as WHO) 2010 classification[17], consisting of LGIN,HGIN, MC, and SMC[18]. The final diagnosis was established with endoscopically or surgically resected specimens when the diagnosis of resected specimens was different from that of preoperatively biopsied specimens[6].

Outcomes

Figure 2 The endoscopic submucosal dissection method of superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumors. Type 0-IIa lesion, 25 mm × 25 mm, mucosal carcinoma, cut-end negative. A: Flat, elevated-type lesion was located in the second portion of the duodenum; B: Performing circumferential incision and submucosal dissection; C:Ulcer findings just after lesion removal. The lesion was resected en bloc, and there was no bleeding or perforation in the ulcer just after the procedure; D: After 2 mo of endoscopic submucosal dissection, the wound became a scar, and no residual tumor was found.

The primary endpoint was the long-term outcome of endoscopically treated SNADETs, including local recurrence and disease-specific mortality, for patients who were under surveillance with an endoscopic observation for 12 mo or longer after ER.The secondary endpoint was short-term outcomes of ER including en bloc resection rates and R0 resection rates, and adverse events. Complete (R0) resection was defined as en bloc resection with tumor-free margins.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range (IQR)) and were compared using Student’s t test or the Mann-Whitney U test. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare data pertaining to categorical variables. A probability value (P-value) of < 0.05 was considered significant. Stata software version 14 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, United States) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

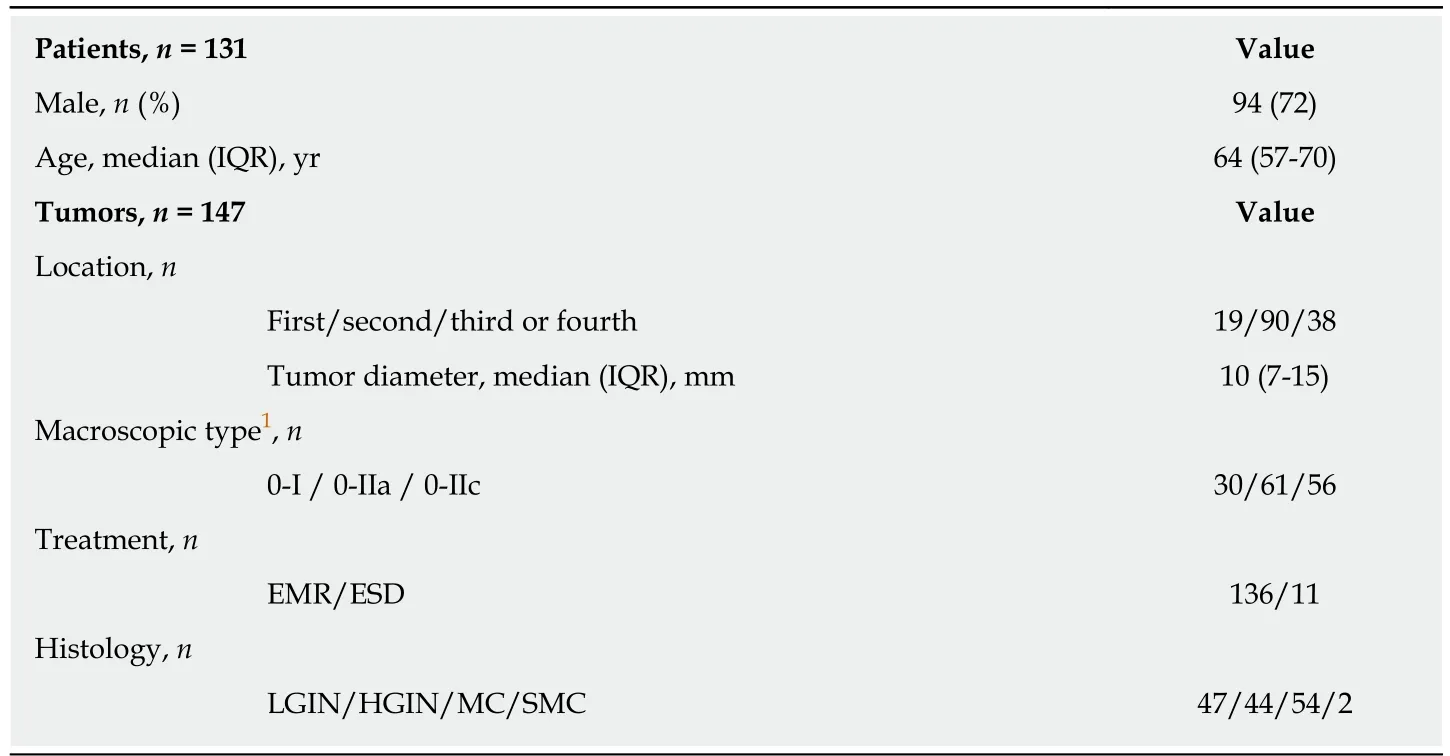

One hundred and thirty-one patients with 147 SNADETs were analyzed. The patient and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Ninety-four of the one hundred and thirty-one patients (72%) were men, and the median age was 64 yr. Ninety (61%)and thirty-eight (26%) lesions of 147 SNADETs were located in the second portion and the third or fourth portion, respectively. The median tumor diameter was 10 mm.Thirty (20%), sixty-one (42%), and fifty-six (38%) lesions showed protruded (0-I),slightly elevated (0-IIa), and depressed (0-IIc) macroscopic type, respectively. Final histology showed that 47 (32%) were LGIN, 44 (30%) HGIN, 54 (37%) MC, and 2 (1%)SMC. EMR and ESD were performed for 136 (93%) and 11 (7%) SNADETs,respectively.

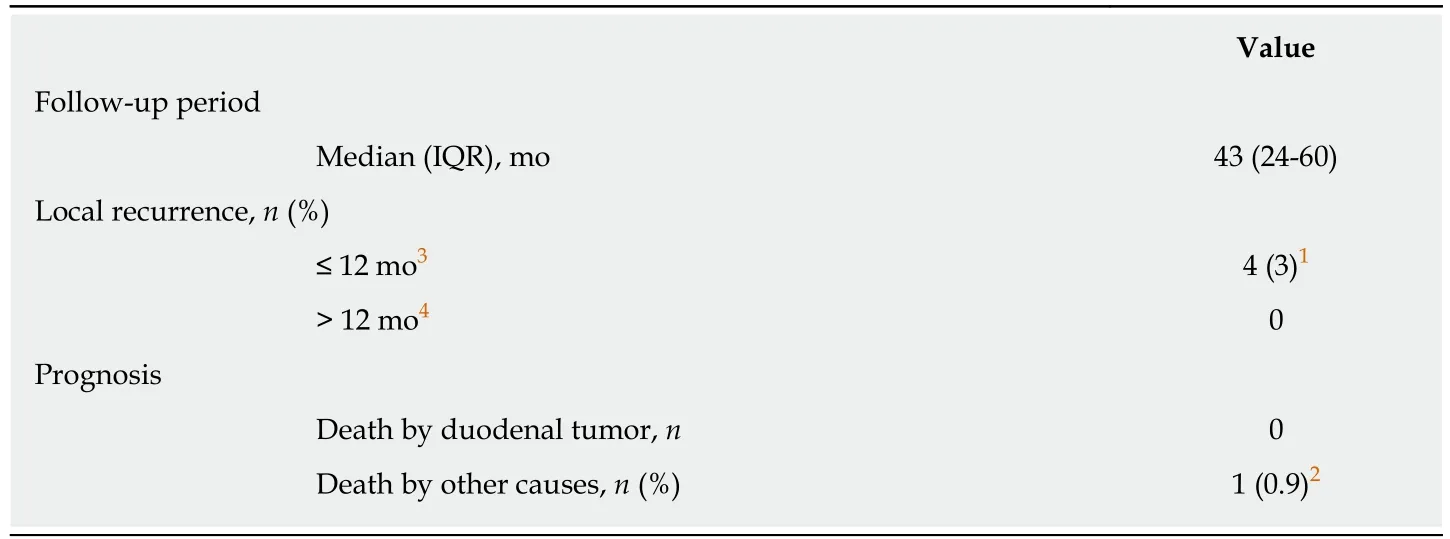

Table 2 shows the long-term outcomes of the 121 patients with 135 SNADETs who were under surveillance with an endoscopic observation for 12 mo or longer after ER.The median follow-up period was 43 mo (IQR: 24-60). Local recurrence was found in 4 EMR cases within 12 mo after ER. All recurrence lesions were initially treated by piecemeal EMR (n = 2) or en bloc EMR with RX (n = 1) or R1 (n = 1). Eventually, those lesions were completely treated endoscopically.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients and tumors

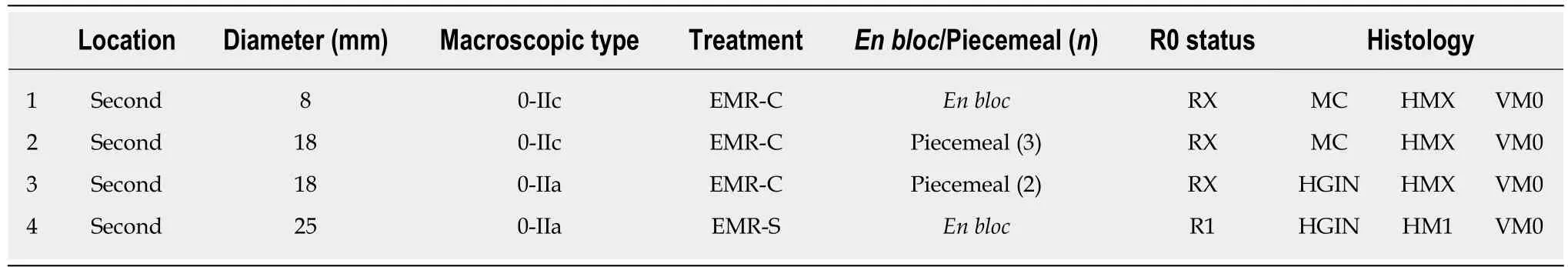

There was no case of local recurrence in more than 12 mo after ER. Also, no recurrence was noted in 88 cases treated by ER with R0 resection in the follow-up period. No treatment-related death occurred and none of the patients died of SNADET. One patient died of congestive heart failure during the follow-up period.Table 3 shows the details of recurrence cases. All the cases with tumor recurrence occurred after EMR with piecemeal or R1 or RX resection. Table 4 shows the shortterm outcomes and adverse events related EMR.

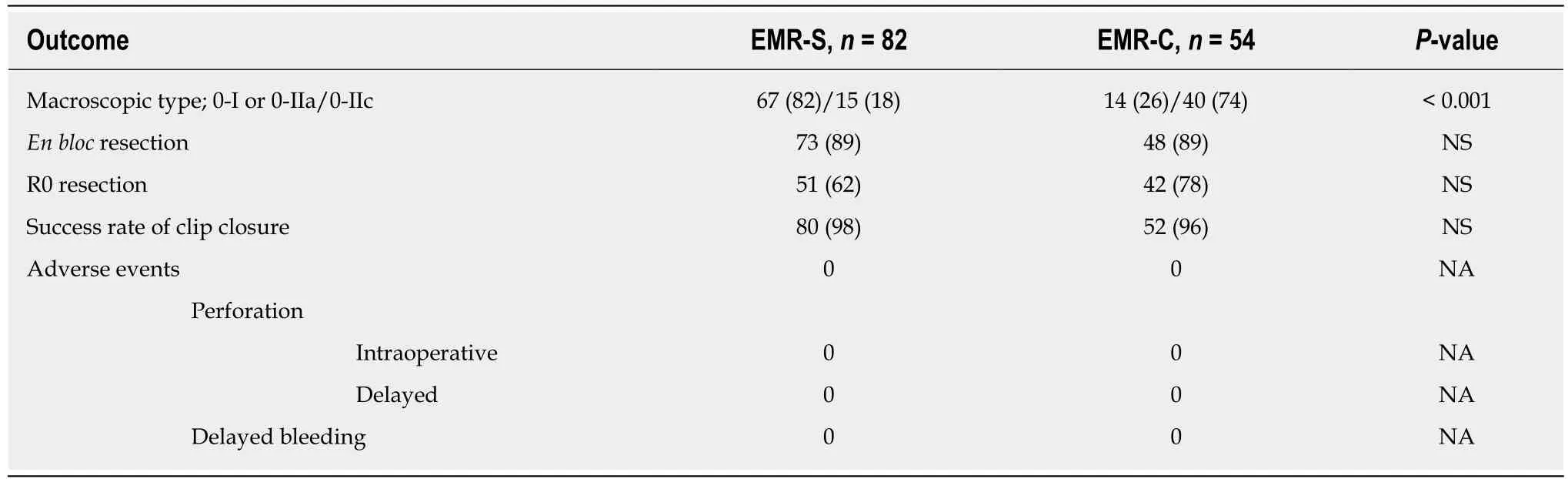

In the EMR cases, 82 (60%) and 54 (40%) tumors were resected with EMR-S and EMR-C, respectively. EMR-S was more frequently used for protruded (0-I) or slightly elevated (0-IIa) tumors than EMR-C for depressed (0-IIc) tumors (82% vs 26%, P <0.001). En bloc and R0 resection rates of EMR-S and EMR-C were 89%/62%, and 89%/78%, respectively. EMR-C showed a higher rate of R0 resection compared to EMR-S (78% vs 62%, P = 0.06) (Figure 3). No adverse event occurred in the EMR cases.Table 5 shows the short-term outcomes and adverse events related EMR vs ESD.

The median size of lesions treated by ESD was larger than EMR (20 mm vs 9 mm, P< 0.001). Delayed bleeding, intraoperative perforations, and delayed perforations occurred in 1, 3, and 2 of the ESD cases, respectively. One of the three cases of intraoperative perforation required emergency surgery. In 2 SMC cases, surgical resection was performed after EMR. One case had an SM invasion depth of 500 μm and no vascular invasion and was negative for resection margin, whereas the other had an SM invasion depth of 1000 μm, mild invasion to vessels, and absence of lymphatic invasion, and was negative for VM0 and HMX. Additional surgical partial resection of the duodenum was performed in both patients with SMCs, with no recurrence or metastasis at 3 yr after ER.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study, we evaluated therapeutic outcomes of ER for SNADETs in order to clarify the safety, efficacy, and curability of ER in such patients. The longterm prognosis was favorable regardless of the ER technique employed, as no recurrence was noted at more than 12 mo after ER, and no disease-specific death occurred.

This is the third largest case series of patients with SNADETs who were treated via ER[7,9,12,19-23]. While this study included few patients treated by ESD, we report the largest number of EMR-C patients; this is particularly relevant for depressed-type SNADET lesions that would be difficult to resect via EMR-S. In this series of SNADET patients, all EMR procedures, including EMR-C, were completed without adverse events and no EMR-related complications were noted on follow-up. Although some ESD-treated patients experienced adverse events, previous studies showed a wide variation of local recurrence rates, ranging from 0% to 37.8% after ER of SNADETs[8,9,21,24,25].

Our study demonstrated excellent long-term outcomes of ER for SNADETs becausethe recurrence rate was only 3%, and no one died of SNADET in the median followup period of 43 mo, longer than 3 yr. There are two likely explanations for the small recurrence rate noted in this study. First, tumor diameter of SNADET in this study was smaller than those in other published studies[24,27]. Second, we used magnifying endoscopy to observe marginal areas of mucosal defect immediately after ER precisely. If we found a suspected lesion of residual tumor, we performed additional coagulation therapy by using argon plasma or hot biopsy. Tumor recurrence occurred only after piecemeal resection or en bloc resection with RX or R1, and all recurrent tumors were identified within 12 mo after EMR. Therefore, strict follow-up in a short interval will be required in such patients.

Table 2 Long-term outcomes of endoscopic resection for 121 patients with 135 superficial nonampullary duodenal epithelial tumors

The incidence of depressed (0-IIc) type of SNADETs was higher in our case series than in previous studies (38% vs 5%-26% of SNADETs analyzed)[6,8,9,26,27]. Furthermore,the depressed type tumors were resected using the EMR-C method significantly more often than the EMR-S method in this study. As we found a higher rate of R0 resection for EMR-C than for EMR-S, we believe that EMR-C will be a more suitable method for depressed type SNADETs than EMR-S. Interestingly, we found no EMR-associated adverse events regardless of technique (EMR-C or EMR-S), whereas previous studies reported a higher incidence of adverse events for EMR-C than for EMR-S[23,24,28].During EMR-C, the step involving sucking the lesion carries the risk of perforation[29].We must always be careful to avoid perforation during EMR-C for a duodenal tumor,because the muscularis propria layer of the duodenum is very thin.

We recommend the following procedures of EMR-C, namely the “suck and shake”technique: (1) sucking on a target area after submucosal injection and closing of the snare, followed by (2) slightly loosening o the snare and shaking it. Considering no perforation occurred in EMR cases in this study, the “suck and shake” technique may work to release entrapment of the muscularis propria layer and avoid perforation.Neither intraoperative nor delayed perforation could be avoided in ESD-treated patients, likely because we failed to completely close or cover the mucosal defect using clipping or tissue shielding. We expect that the development of simpler endoscopic techniques for closing or shielding large mucosal defects may help reduce the incidence of delayed perforation.

Based on our present findings, relatively small lesions (< 20 mm) represented a good indication for EMR, as en bloc resection was achieved for most such tumors, with no local recurrence. ESD was mainly performed for larger lesions (≥ 20 mm). The en bloc resection rate was higher for ESD than for EMR (100% vs 89%), and no recurrence was noted after ESD. We found no EMR-related adverse events in this series of SNADET patients. Studies on EMR for SNADETs reported an incidence of 0-33% for delayed bleeding[9,21,24,28,30-33]and 0-4% for perforation (intraoperative or delayed)[9,22,30,34,35]. On the other hand, studies on ESD for SNADETs reported an incidence of 0-18.4% for delayed bleeding[8,26,27,36]and 0-50% for perforation[21,25,37-39].

Thus, our present findings confirm previous data suggesting that perforation rates are considerably higher for ESD than for EMR, though the absence of adverse events following EMR may affect the statistical robustness of these conclusions. Although ESD allows en bloc resection even for large lesions, the decision to perform ESD should be taken in full consideration of all circumstances, and duodenal ESD should be performed by a skillful endoscopist. Taken together, these observations suggestthat EMR may become the standard endoscopic treatment for SNADETs, particularly if the lesions are relatively small.

Table 3 Characteristics of recurrence cases after endoscopic resection

We generally avoided taking a biopsy during preoperative endoscopy. The reasons are that the fibrosis after biopsy can increase the risk of perforation due to poor mucosal lifting and the diagnostic accuracy of preoperative biopsy may not be highly reliable. In fact, a multicenter case-series study showed that the overall accuracy of the preoperative diagnosis was significantly higher in endoscopic diagnosis than in histology from biopsy (endoscopy and biopsy, 75% and 68%, respectively)[6]. The other study also showed similar results that the accuracy of endoscopic diagnosis is superior to that of biopsy (endoscopy and biopsy, 78% and 74%, respectively) in preoperative endoscopy[40].

This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective, single-center study. Furthermore, we could not follow-up some patients, although the number of such patients was low (7.6%, 10/131). Second, very few ESD procedures were performed in this series. To confirm our present findings and promote the standardization of ER for SNADETs, future studies should have multi-center sampling and a prospective design.

In conclusion, this study suggests that ER would provide good long-term outcomes in patients with SNADETs, albeit a high incidence of adverse events is associated with ESD. EMR should be a first-line treatment for SNADETs, especially small lesions.

Table 4 Short-term outcomes and adverse events (EMR-S vs EMR-C)

Table 5 Short-term outcomes and adverse events (endoscopic mucosal resection vs endoscopic submucosal dissection)

Figure 3 The study flow diagram based on the therapeutic outcomes of endoscopic resections. EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; EMR-S: Conventional method with snare; EMR-C: Cap-assisted EMR; R0: En bloc resection with tumor-free margins histopathologically; RX:Involvement of the horizontal and/or vertical margin could not be assessed histopathologically; R1: Involvement of the horizontal and/or vertical margin histopathologically; AC: Adenocarcinoma; HGIN: High-grade intraepithelial neoplasia; LGIN: Low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Endoscopic resection (ER) for superficial non-ampullary duodenal epithelial tumor (SNADET) is a challenging technique, due to the anatomical peculiarity of the procedure and the high frequency of the adverse event. Moreover, there are few reports on the treatment outcome of ER in many cases because of its relative rarity.

Research motivation

We aimed to determine the standardized criteria for endoscopic management of SNADNETs.

Research objectives

Based on the research background, we analyzed the results of the short-term and long-term treatment of over 100 cases of SNADET and investigated the effectiveness of ER in these cases.

Research methods

This study analyzed the short- and long-term outcomes of ER. Short-term outcomes of ER included en bloc and R0 resection rates, as well as the adverse events. Long-term outcomes included local recurrence detected on endoscopic surveillance and disease-specific mortality in patients followed up for ≥ 12 mo after ER. This retrospective study included a case series of 131 patients (147 SNADETs) who underwent endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) between March 2004 and July 2017.

Research results

Over a median follow-up of 43 mo, recurrence was found in four lesions and those were treated endoscopically. No adverse events were observed in EMR-treated patients, whereas ESD for SNADETs carries a risk of bleeding and perforation. No patient died due to tumor recurrence.

Research conclusions

Our findings suggest that ER provides good long-term outcomes in patients with SNADETs.EMR was not associated with any adverse events and, therefore, could be considered as a standard treatment for small SNADETs.

Research perspectives

For small SNADETs, EMR is likely to become the standard treatment strategy.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年6期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年6期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Body-mass index correlates with severity and mortality in acute pancreatitis: A meta-analysis

- Serum hepatitis B virus RNA is a predictor of HBeAg seroconversion and virological response with entecavir treatment in chronic hepatitis B patients

- Preoperative rectosigmoid endoscopic ultrasonography predicts the need for bowel resection in endometriosis

- Effect of Sheng-jiang powder on multiple-organ inflammatory injury in acute pancreatitis in rats fed a high-fat diet

- Artificial intelligence in medical imaging of the liver

- Cancer risk in primary sclerosing cholangitis: Epidemiology,prevention, and surveillance strategies