Insulin resistance is associated with subclinical vascular disease in humans

María M Adeva-Andany, Eva Ameneiros-Rodríguez, Carlos Fernández-Fernández,Alberto Domínguez-Montero, Raquel Funcasta-Calderón

Abstract Insulin resistance is associated with subclinical vascular disease that is not justified by conventional cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking or hypercholesterolemia. Vascular injury associated to insulin resistance involves functional and structural damage to the arterial wall that includes impaired vasodilation in response to chemical mediators, reduced distensibility of the arterial wall (arterial stiffness), vascular calcification, and increased thickness of the arterial wall. Vascular dysfunction associated to insulin resistance is present in asymptomatic subjects and predisposes to cardiovascular diseases, such as heart failure, ischemic heart disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease.Structural and functional vascular disease associated to insulin resistance is highly predictive of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Its pathogenic mechanisms remain undefined. Prospective studies have demonstrated that animal protein consumption increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease and predisposes to type 2 diabetes (T2D) whereas vegetable protein intake has the opposite effect. Vascular disease linked to insulin resistance begins to occur early in life. Children and adolescents with insulin resistance show an injured arterial system compared with youth free of insulin resistance, suggesting that insulin resistance plays a crucial role in the development of initial vascular damage. Prevention of the vascular dysfunction related to insulin resistance should begin early in life. Before the clinical onset of T2D, asymptomatic subjects endure a long period of time characterized by insulin resistance. Latent vascular dysfunction begins to develop during this phase, so that patients with T2D are at increased cardiovascular risk long before the diagnosis of the disease.

Key words: Diabetes; Cardiovascular risk; Arterial stiffness; Arterial elasticity; Intimamedia thickness; Vascular calcification; Insulin resistance; Animal protein; Vegetable protein

INTRODUCTION

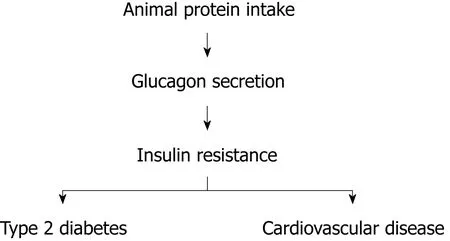

Cardiovascular disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality particularly in patients with diabetes. Cardiovascular risk in this population group begins decades prior the clinical diagnosis of the disease and is not fully explained by traditional risk factors such as hypercholesterolemia and smoking. Multiple investigations provide compelling evidence of an association between insulin resistance by itself and cardiovascular risk in the general population and patients with diabetes. More insulin-resistant subjects endure higher cardiovascular risk compared to those who are more insulin-sensitive[1]. A causative link between insulin resistance by itself and vascular disease is very likely to exist, but the pathogenic mechanisms that explain the vascular dysfunction related to insulin resistance remain elusive. There is conclusive evidence that dietary habits that include animal protein increase the risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and cardiovascular disease whereas dietary patterns with elevated content of vegetable protein reduce the risk of both disorders[2]. Population groups that change their dietary routine to augment animal protein intake experience a dramatic increase in the rate of T2D and cardiovascular events[3]. Animal protein consumption activates glucagon secretion. Glucagon is the primary hormone that opposes insulin action. Animal protein ingestion may predispose to T2D and cardiovascular events by intensifying insulin resistance via glucagon secretion (Figure 1)[4].

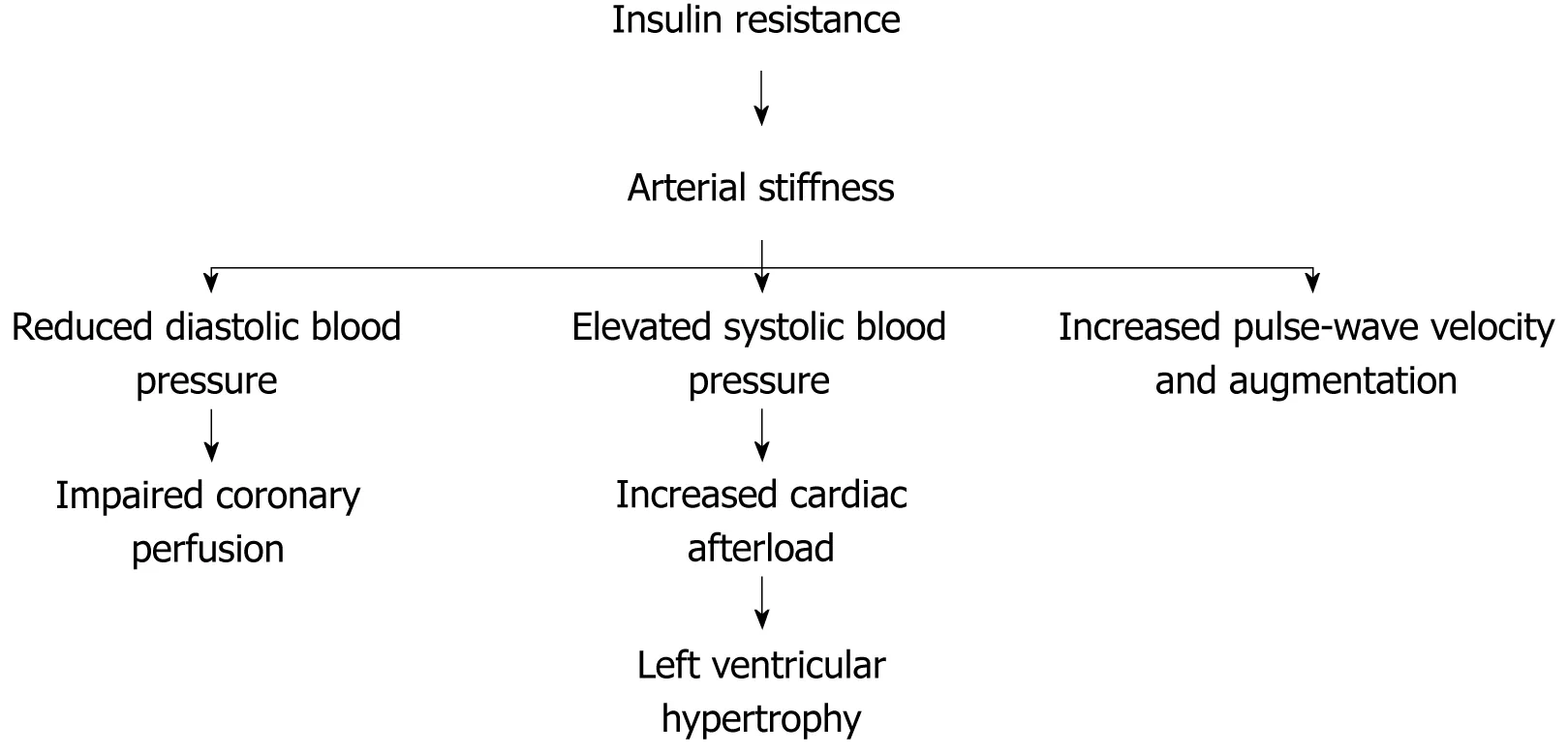

Asymptomatic individuals with insulin resistance experience striking vascular damage that is not justified by traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypercholesterolemia or smoking. Vascular injury related to insulin resistance develops progressively in asymptomatic subjects during a period of time that may begin during childhood. A long phase of insulin resistance and latent vascular injury precedes the clinical onset of T2D increasing cardiovascular risk before the diagnosis of the disease[5-7]. Accordingly, subclinical vascular dysfunction is evident in patients with screen-detected T2D[8]. Vascular damage associated with insulin resistance includes functional and structural vascular injury, such as impaired vasodilation, loss of elasticity of the arterial wall (arterial stiffness), increased intima-media thickness of the arterial wall, and vascular calcification. (Figure 2) The presence of subclinical vascular disease associated with insulin resistance is highly predictive of future cardiovascular events[9-12].

INSULIN RESISTANCE IS INDEPENDENTLY ASSOCIATED WITH SUBCLINICAL IMPAIRMENT OF VASCULAR REACTIVITY

Figure 1 A simplified proposed mechanism underlying vascular disease associated with insulin resistance.

Vascular smooth muscle cells normally undergo contraction or relaxation to regulate the magnitude of the blood flow according to physiological conditions. Normal endothelial cells generate vasoactive substances that modulate the reactivity of vascular smooth muscle cells. Among them, nitric oxide is a short-lived gas that induces vasodilation. Acetylcholine is an endogenous transmitter that activates endothelial nitric oxide production by acting on muscarinic receptors. Acetylcholine induces endothelium-dependent vasodilation while exogenous sources of nitric oxide(such as nitroglycerin and sodium nitroprusside) induce endothelium-independent vasodilation. In response to increased blood flow, vascular smooth muscle cells normally relax to produce vasodilation and accommodate the elevated blood flow.Flow-mediated vasodilation is attributed to nitric oxide release by endothelial cells.The degree of flow-mediated vasodilation is considered a measure of endotheliumdependent vasodilation and can be determined by ultrasonography performed at the brachial artery[13-15].

A number of investigations show that insulin resistance is independently associated with blunted flow-mediated arterial vasodilation in asymptomatic healthy individuals compared to control subjects[5,16,17].

Similarly, insulin resistance is associated with limited vasodilation in response to metacholine chloride, a muscarinic agent. The increment in blood flow in response to metacholine is lower in insulin-resistant subjects compared to insulin-sensitive controls[18].

Likewise, arterial response to exogenous sources of nitric oxide, such as nitroglycerin, sodium nitroprusside, and nitrates is impaired in subjects with insulin resistance compared to control subjects[10,16,18].

Similarly to healthy subjects, flow-mediated vasodilation is defective in nondiabetic patients with coronary heart disease, compared to control subjects. On multivariate analysis, the extent of flow-mediated vasodilation is correlated with serum highdensity lipoprotein (HDL)-c, but not with low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-c or total cholesterol levels[10].

Impairment of flow-mediated vasodilation associated with insulin resistance is already apparent in childhood. Obese children show impaired arterial vasodilation compared to control children. Further, regular exercise over 6 mo restores abnormal vascular dysfunction in obese children. The improvement in flow-mediated vasodilation after 6-mo exercise program correlates with enhanced insulin sensitivity,reflected by reduced body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio, systolic blood pressure, fasting insulin, triglycerides, and LDL/HDL ratio[19].

In normal weight and overweight adolescents, there is a gradual deterioration of flow-mediated vasodilation with worsening of insulin resistance evaluated by the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp[20].

INSULIN RESISTANCE IS INDEPENDENTLY ASSOCIATED WITH SUBCLINICAL ARTERIAL STIFFNESS

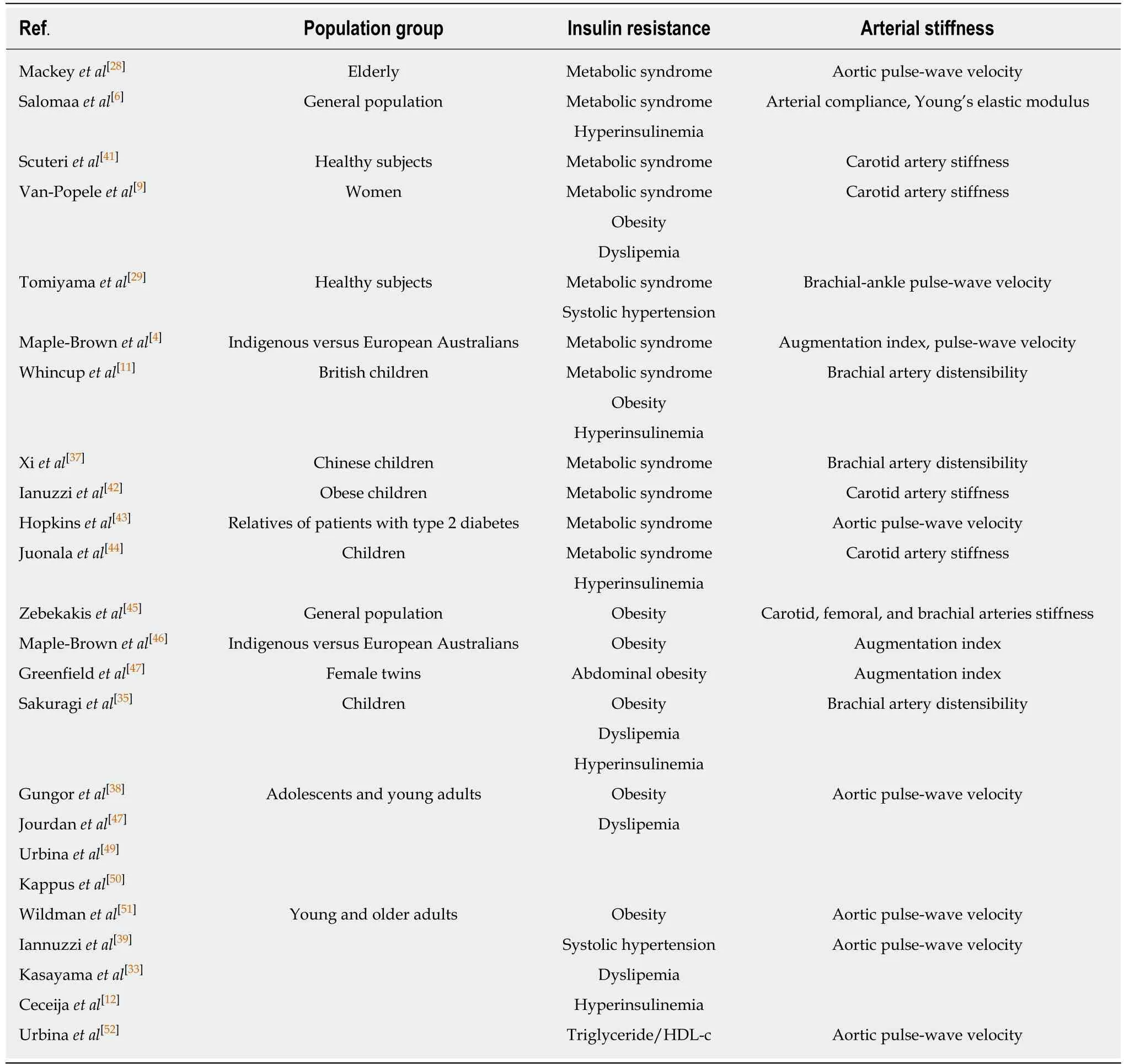

Loss of distensibility of the arterial wall (arterial stiffness) leads to elevated systolic blood pressure and consequently increases cardiac afterload resulting in left ventricular hypertrophy that contributes to the development of congestive heart failure. In addition, arterial stiffness leads to reduced diastolic blood pressure, which may deteriorate diastolic coronary blood flow contributing to ischemic heart disease[21,22](Figure 3). Arterial stiffness is associated with wide pulse pressure(systolic blood pressure minus diastolic blood pressure)[7,23].

Parameters that estimate arterial stiffness include blood pressure, pulse pressure,pulse-wave velocity, augmentation index, coefficients of distensibility and compliance, and the Young’s elastic modulus, which includes intima-media thickness and estimates arterial stiffness controlling for arterial wall thickness[6]. Pulse-wave velocity is the speed of the pressure wave generated by left ventricular contraction.Arterial stiffness impairs the ability of the arterial wall to cushion the pressure wave and increases pulse-wave velocity[21]. Augmentation is the pressure difference between the second and first systolic peaks of the central arterial pressure waveform.Increased augmentation reflects arterial stiffness[24,25]. The augmentation index has been defined as augmentation divided by pulse pressure, being a measure of peripheral wave reflection. A higher augmentation index reflects increased arterial stiffness[26,27].

Figure 2 Pathophysiological changes associated with insulin resistance-mediated vascular disease.

Age is consistently associated with arterial stiffness, but the loss of arterial elasticity related with age is not justified by conventional cardiovascular risk factors. Insulin resistance becomes deeper with age and may be a major pathophysiological determinant of arterial stiffness in the elderly population[12,28,29].

Numerous investigations document an association between insulin resistance and subclinical arterial stiffness in nondiabetic individuals across all ages. Arterial stiffness related to insulin resistance begins early in life and progresses in asymptomatic subjects during a latent period of time before the diagnosis of cardiovascular disease. Subclinical arterial stiffness associated with insulin resistance strongly predicts future cardiovascular events. Conventional cardiovascular risk factors do not explain the loss of arterial elasticity related to insulin resistance[7,22].

Arterial stiffness is apparent in asymptomatic subjects with insulin resistance ascertained either by its clinical expression, the metabolic syndrome, or by estimates of insulin sensitivity.

Estimates of insulin resistance are associated with subclinical arterial stiffness

In a variety of population groups, insulin resistance identified by different estimates is consistently associated with measures of arterial stiffness independently of classic cardiovascular risk factors (Table 1).

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study is a prospective population-based trial with African American and Caucasian participants. A cross-sectional analysis showed an independent association between insulin resistance (assessed by glucose tolerance tests) and arterial stiffness. Subjects with insulin resistance had stiffer arteries compared to those with normal glucose tolerance after adjustment for confounding factors[6].

Similarly, insulin resistance (glucose tolerance tests) in individuals from the general population was independently associated with arterial stiffness estimated by distensibility and compliance of the carotid, femoral and brachial arteries, compared to normal glucose tolerance. Arterial stiffness worsened with deteriorating glucose tolerance[22].

Comparable findings were obtained in healthy Chinese subjects. Insulin resistance(impaired glucose tolerance) was independently associated with arterial stiffness(estimated by brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity) compared to normal glucose tolerance. Normoglycemic subjects with altered glucose metabolism have increased arterial stiffness[30].

Likewise, arterial stiffness (brachial artery pulse-wave velocity) is positively correlated with postprandial glucose and negatively correlated with plasma adiponectin level, suggesting that arterial stiffness is greater in patients with insulin resistance compared to those with normal glucose tolerance[17].

Assessment of insulin resistance with the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp is also independently associated with subclinical arterial stiffness of the common carotid and femoral arteries evaluated by pulse-wave velocity in asymptomatic healthy adults[21]. In patients with hypertension, insulin resistance (glucose tolerance tests) is independently associated with arterial stiffness (carotid-femoral pulse-wave velocity and pulse pressure) as well[31,32].

Several studies document an association between insulin resistance evaluated by the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) index and arterial stiffness in asymptomatic individuals from different population groups. In healthy subjects and in Korean post-menopausal women, insulin resistance is independently associated with increased arterial stiffness (evaluated by brachial-ankle, aortic and peripheral pulse-wave velocity). Arterial stiffness increases sequentially with the degree of insulin resistance[33,34]. Analogous findings are observed in normotensive normoglycemic first-degree relatives of patients with diabetes. Arterial stiffness(carotid-femoral pulse-wave velocity) is increased in the relatives with insulin resistance compared to those more insulin-sensitive[35]. Insulin resistance and arterial stiffness (augmentation index and pulse-wave velocity) were compared in Indigenous Australians (a population group with elevated rate of T2D) and European Australians. The Indigenous population group had higher HOMA-IR values and increased arterial stiffness compared to their European counterparts, suggesting that intensified insulin resistance among Indigenous participants contributes to explain increased arterial stiffness in this group[4].

Figure 3 Cardiovascular disease associated to arterial stiffness.

Subclinical arterial stiffness is already present in children and adolescents with insulin resistance, compared to insulin-sensitive control subjects. In healthy children and adolescents from the general population of different countries, insulin resistance(HOMA-IR values) is independently associated with increased arterial stiffness evaluated by carotid-femoral pulse-wave velocity or brachial artery distensibility compared to control subjects[11,36,37]. In obese children and adolescents, a profound independent effect of insulin resistance on vascular compliance has been observed.Insulin-resistant subjects (HOMA-IR) experience increased vascular stiffness (aortic pulse-wave velocity) compared to control individuals[38-40]. In normal weight and overweight adolescents, insulin resistance assessed by euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp is associated with higher augmentation index, indicating that insulin resistance in adolescents is related to increased arterial stiffness[20].

Clinical manifestations of insulin resistance are associated with subclinical arterial stiffness

The metabolic syndrome is a cluster of clinical features that reflects insulin resistance,including obesity, systolic hypertension, dyslipemia (hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL-c), and hyperinsulinemia. The metabolic syndrome and its individual components have been independently associated with arterial stiffness. Patients with any clinical expression of insulin resistance experience subclinical arterial stiffness that is not explained by conventional cardiovascular risk factors. Arterial stiffness has been considered a further clinical manifestation of insulin resistance[7](Table 2).

The metabolic syndrome is associated with arterial stiffness:The longitudinal association between the metabolic syndrome and arterial stiffness was investigated in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Metabolic syndrome at baseline (obesity, systolic hypertension, hyperinsulinemia and hypertriglyceridemia) independently predicted increased arterial stiffness (aortic pulse-wave velocity) at follow-up[28].

In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, the joint effect of elevated glucose, hyperinsulinemia and hypertriglyceridemia (reflecting insulin resistance) is independently associated with arterial stiffness in subjects from the general population[6]. Similarly, the clustering of at least three components of the metabolic syndrome is related with increased carotid artery stiffness among healthy participants across all age groups in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging independently of other cardiovascular risk factors[41].

Likewise, the metabolic syndrome is strongly and independently associated with reduced distensibility of the common carotid artery in healthy women from the general population[9]. In 12517 subjects with no history of cardiovascular disease,systolic hypertension, obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and hyperuricemia are independent determinants for arterial stiffness (brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity)on multiple regression analysis[29]. Arterial stiffness (augmentation index and pulsewave velocity) was compared in Indigenous and European Australians. Factoranalysis revealed that metabolic syndrome components clustered with Indigenous Australian participants. Arterial stiffness was more pronounced among Indigenous compared to European Australians[4].

Subclinical arterial stiffness is already present in children and adolescents with the metabolic syndrome, suggesting that insulin resistance plays an important role in the early pathogenesis of vascular disease. British and Chinese children and adolescents with the metabolic syndrome have increased arterial stiffness compared to control children after adjustment for covariates. There is a strong graded inverse relationship between the number of metabolic syndrome components and brachial artery distensibility[11,37]. In obese children, common carotid artery stiffness is more prominent in the group with the metabolic syndrome compared to the control group[42]. Normoglycemic young adults (mean age 20 years) with a positive family history of T2D have higher BMI and fasting insulin and increased arterial stiffness(aortic pulse-wave velocity) than their counterparts without T2D relatives[43]. The longitudinal relationship between the metabolic syndrome identified in childhood and arterial elasticity assessed in adulthood was investigated in a prospective population-based cohort study with 21 years of follow-up, the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Childhood metabolic syndrome (obesity, systolic hypertension,hypertriglyceridemia and hyperinsulinemia) predicts independently carotid artery stiffness in adulthood[44].

Obesity is associated with arterial stiffness:Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies consistently show that measures of adiposity (BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, body fat, and abdominal fat) are independently associated with estimates of arterial stiffness in diverse population groups. This association is already apparent during childhood and cannot be explained by traditional cardiovascular risk factors.In a population-based setting, adulthood obesity (BMI and waist-to-hip ratio) is associated with increased stiffness of carotid, femoral, and brachial arteries after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors. Arterial distensibility consistently decreased with higher BMI[9,45]. Similarly, obesity (BMI and waist circumference) is independently related to increased arterial stiffness (augmentation index) in Indigenous Australians free of T2D compared to European Australians[46]. In female twins, abdominal adiposity is a determinant of arterial stiffness (augmentation index)independent of genetic effects and other confounding factors[47].

The association between adiposity parameters and increased arterial stiffness begins during childhood. In obese children, there is a marked effect of insulin resistance associated with obesity on vascular compliance. Obese children are more insulin-resistant and have stiffer arteries compared with lean controls[39,40]. In a population-based setting, childhood obesity (BMI and waist circumference) isassociated with increased arterial stiffness after adjustment for confounding factors.There is a strong graded inverse relationship between BMI and brachial artery distensibility, This association is apparent even at BMI levels below those considered to represent obesity[11,36]. Similar results are observed in adolescents and young adults.Obesity is associated with subclinical arterial stiffness independently of cardiovascular risk factors[38,48-50].

Table 2 Studies that find an independent association between the clinical expression of insulin resistance and subclinical arterial stiffness unexplained by classic cardiovascular risk factors

The association between obesity and arterial stiffness (aortic pulse-wave velocity)was evaluated in young adults (20 to 40 years, 50% African American) and older adults (41 to 70 years, 33% African American). Obesity parameters (BMI, waist circumference, hip circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio) were strongly correlated with higher aortic pulse-wave velocity, independently of risk factors. Obesity is an independent and strong predictor of aortic stiffness for both races and age groups[51].

Systolic hypertension, dyslipemia, and hyperinsulinemia are associated with arterial stiffness:Other clinical manifestations of insulin resistance, including systolic hypertension[12,29,39,40], dyslipemia[9,33,36,38-40,52], and hyperinsulinemia[6,11,36,40,44]are also consistently associated with different measures of arterial stiffness independently of other cardiovascular risk factors, in diverse population groups, across all ages.Longitudinal studies such as the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis have shown that arterial stiffness predicts the development of systolic hypertension[53,54]. In healthy subjects 10 to 26 years old,triglyceride-to-HDL-c ratio is an independent predictor of arterial stiffness after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors, particularly in the obese. Arterial stiffness rose progressively across tertiles of triglyceride-to-HDL-c ratio[52].

INSULIN RESISTANCE IS INDEPENDENTLY ASSOCIATED WITH SUBCLINICAL STRUCTURAL CHANGES OF THE ARTERIAL WALL

Similarly to arterial stiffness, a gradual increase in carotid intima-media thickness occurs with age. A systematic review documents a strong association between age and carotid intima-media thickness in healthy subjects and individuals with cardiovascular disease. This relationship is not affected by cardiovascular risk factors.Ageing is associated with magnification of insulin resistance that may explain the increase in intima-media thickness[55].

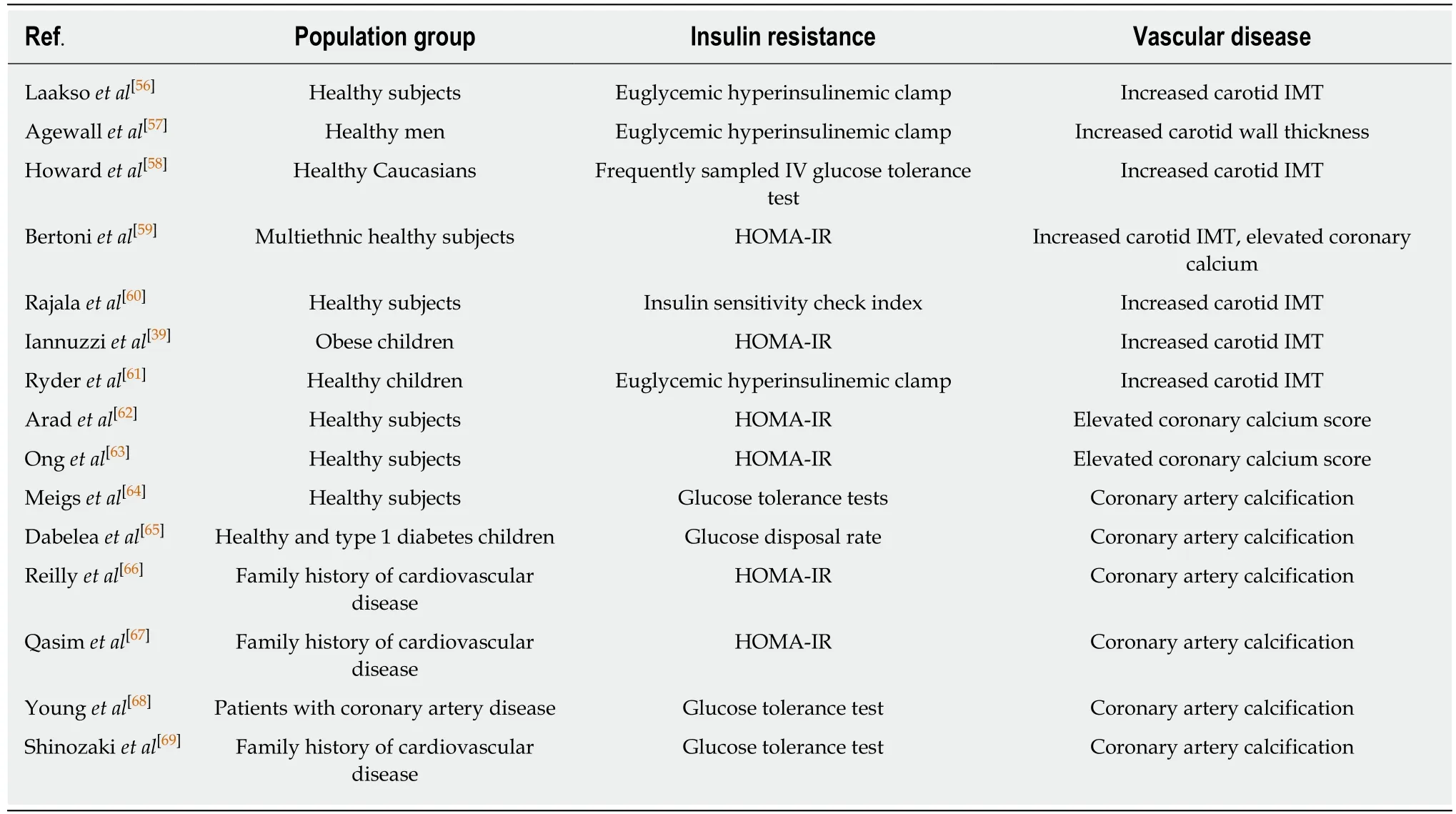

Insulin resistance either ascertained by estimates or by its clinical expression is associated with increased intima-media thickness and increased calcification of the arterial wall in asymptomatic subjects. This association is not mediated by classic cardiovascular risk factors, suggesting that insulin resistance plays a crucial role in the development of initial vascular damage (Table 3).

Estimates of insulin resistance are associated with increased thickness of the arterial wall and increased coronary calcification

Increased thickness of the arterial wall: In healthy subjects from the Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor study, insulin resistance was determined by the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp technique and the presence of subclinical vascular disease in the femoral and carotid arteries was evaluated by ultrasonography. Subjects with asymptomatic vascular disease were more insulin-resistant compared to control subjects[56].

The association between insulin resistance and subclinical vascular disease was confirmed in healthy Swedish men. Insulin resistance was determined by the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp in subjects with high cardiovascular risk(hypercholesterolemia, smoking) and subjects with no cardiovascular risk factors.Asymptomatic vascular disease was evaluated by B-mode ultrasound of the common carotid artery. A negative correlation between insulin sensitivity and carotid intimamedia thickness was observed in both population groups (high and low cardiovascular risk). Participants with insulin resistance had greater carotid wall thickness compared to insulin-sensitive subjects[57].

A similar association between insulin resistance and subclinical vascular disease(increased intima-media thickness of the arterial wall) was observed in healthy Caucasian participants of the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Insulin sensitivity was evaluated by the frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test with analysis by the minimal model of Bergman. Asymptomatic vascular disease was assessed by the measurement of intima-media thickness of the carotid artery by B-mode ultrasonography. In Caucasian men, insulin resistance is associated with a subclinical increase in carotid intima-media thickness, after adjustment for traditional cardiovascular risk factors[58].

The independent association between insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and subclinical vascular disease (increased carotid intima-media thickness) has been confirmed in healthy subjects of four ethnic groups (non-Hispanic Whites, African-Americans,Hispanic Americans, and Chinese Americans) from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis[59].

In asymptomatic patients with impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance(calculated by the insulin sensitivity check index) is strongly associated with severe carotid atherosclerosis (assessed by ultrasonography) on multiple regression analysis after adjustment for confounders. Carotid intima-media thickness correlated inversely with insulin sensitivity[60].

The association between insulin resistance and asymptomatic increased intimamedia thickness is apparent in childhood. In healthy children, insulin resistance measured with the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp is associated with higher carotid intima-media thickness[61]. Likewise, obese children aged 6-14 years with higher HOMA-IR had increased carotid intima-media thickness compared to control children[39].

Increased coronary artery calcification:Insulin resistance is also associated with subclinical coronary artery calcification. Asymptomatic subjects with insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) have increased coronary calcification score (derived fromelectron-beam computed tomography) that is not explained by traditional cardiovascular risk factors[59,62,63].

Table 3 Studies that find an independent association between insulin resistance and subclinical vascular calcification or increased intima-media thickness of the arterial wall unexplained by traditional cardiovascular risk factors

In the Framingham Offspring Study, there is a graded increase in subclinical coronary artery calcification with worsening insulin resistance (impaired glucose tolerance) among asymptomatic subjects[64].

The association between insulin resistance (estimated glucose disposal rate) and coronary artery calcification was examined among patients with type 1 diabetes and healthy subjects in the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes study. Insulin resistance was independently associated with coronary artery calcification (electronbeam computed tomography) in both population groups[65].

In the Study of Inherited Risk of Coronary Atherosclerosis, insulin resistance(HOMA-IR) is associated with coronary artery calcification after adjustment for confounding factors in asymptomatic subjects with a family history of premature cardiovascular disease. The HOMA-IR index predicts coronary artery calcification scores beyond other cardiovascular risk factors in this population group[66,67].

In normoglycemic patients with coronary artery disease, insulin resistance (glucose tolerance tests) is associated with severity of the coronary disease documented by coronary arteriography compared to control subjects. Nondiabetic patients with coronary artery disease are insulin-resistant compared to control subjects[68,69].

Clinical manifestations of insulin resistance are associated with subclinical structural damage to the arterial wall

The metabolic syndrome and its individual components are associated with subclinical structural vascular disease that is not explained by conventional cardiovascular risk factors.

The metabolic syndrome:In healthy participants of several studies, including the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging study, and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, the metabolic syndrome is independently associated with asymptomatic increased carotid intima-media thickness across all age groups and ethnicities[6,41,59,70]. Likewise, the metabolic syndrome is associated with coronary artery calcification independently of other cardiovascular risk factors in asymptomatic subjects with a family history of premature cardiovascular disease participants of the Study of Inherited Risk of Coronary Atherosclerosis[66].

Subclinical vascular damage is detectable at young age in the presence of metabolic syndrome. Asymptomatic carotid intima-media thickness is increased in children with metabolic syndrome as compared with healthy control children, after adjustment for confounders[71]. Regular exercise over 6 mo improves the metabolic syndrome and reduces carotid intima-media thickness in obese children compared to control subjects[19].

In analyses from four cohort studies (Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study,Bogalusa Heart study, Princeton Lipid Research study, Insulin study) with a mean follow-up of 22.3 years, the presence of the metabolic syndrome during childhood is associated with higher carotid intima-media thickness in adulthood[72].

In the Bogalusa Heart study, postmortem examinations performed in children and adolescents from a biracial (African American and Caucasian) community showed that the antemorten presence of the metabolic syndrome (obesity, dyslipemia, and hypertension) strongly predicted the extent of vascular disease in the aorta and coronary arteries[73].

In the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth study, arteries collected from autopsies aged 15-34 years whose deaths were accidental showed that vascular disease in the aorta and right coronary artery is associated with the presence of impaired glucose tolerance, obesity, hypertension, and low HDL-c level. This association is not explained by hypercholesterolemia or smoking[74].

Obesity:In healthy asymptomatic adults, greater BMI and waist-to-hip ratio are independently associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness[70,75].Increased diameter of the arterial wall associated with obesity is present in several areas of the arterial system, including carotid, femoral and brachial arteries. Across a wide age range, intima-media thickness of several arteries increased with higher BMI in a population-based sample of participants[45].

The independent relationship between obesity and subclinical increased intimamedia thickness of carotid and femoral arteries is present in children and adolescents.Obese children have increased carotid and femoral intima-media thickness compared to control children[39,48,50]. In a prospective cohort of children and adolescents, BMI assessed at 11, 15, and 18 years was associated with higher carotid intima-media thickness after controlling for confounders. Overweight/obese subjects had higher carotid intima-media thickness compared to subjects with normal BMI[76].

In analyses from four cohort studies (Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study,Bogalusa Heart study, Princeton Lipid Research study, Insulin study) with a mean follow-up of 22.3 years, childhood BMI was associated with higher carotid intimamedia thickness in adulthood[72].

Systolic hypertension, dyslipemia, and hyperinsulinemia:Fasting hyperinsulinemia is independently associated with greater carotid intima-media thickness and coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic healthy subjects[6,62,64,70]. The association between hyperinsulinemia and increased carotid intima-media thickness is similar in African American and Caucasian subjects[6,70]. The Mexico City Diabetes study investigated the longitudinal relationship between systolic hypertension and vascular damage in a population-based prospective trial. In normotensive subjects who progress to hypertension (prehypertensive subjects), baseline carotid intima-media thickness increased in comparison with subjects who remained normotensive. After adjusting for multiple cardiovascular risk factors, converter status was independently associated with a higher carotid intima-media thickness[77].

Autopsy examinations from the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth study show that systolic hypertension is associated with greater vascular injury in both the aorta and right coronary artery (particularly fibrous plaques) in subjects throughout the 15-34 year age span. The association of hypertension with vascular damage remained after adjusting for BMI and glycohemoglobin[74].

Longitudinal autopsy studies conducted in children and adults show that low HDL-c is independently associated with vascular disease. The degree of vascular lesions in both the aorta and right coronary artery is negatively associated with serum HDL-c on multiple regression analysis[73,74,78,79].

SUBCLINICAL VASCULAR DISEASE ASSOCIATED WITH INSULIN RESISTANCE PREDICTS CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Subclinical structural and functional vascular dysfunction associated with insulin resistance in otherwise healthy subjects is highly predictive of future cardiovascular events. Reduced vasodilation, loss of arterial distensibility, and increased arterial intima-media thickness in asymptomatic subjects are all associated with future cardiovascular disease.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies, impaired brachial flow-mediated vasodilatation was associated with future cardiovascular events both in asymptomatic and diseased population groups[15]. Impaired nitroglycerin-mediated vasodilatation of the brachial artery has been independently associated with coronary artery calcification in a population-based study[80]. In a prospective study, impaired coronary vasoreactivity was independently associated with a higher incidence of cardiovascular events. Baseline coronary vasoreactivity in response to several stimuli(acetylcholine, sympathetic activation, increased blood flow, and nitroglycerin)predicted incident cardiovascular events at follow-up, after adjustment for traditional cardiovascular risk factors[81].

The ability of arterial stiffness to predict cardiovascular events independently of other cardiovascular risk factors has been documented in cross-sectional and prospective studies, systemic reviews and meta-analyses.

Prospective studies show that increased arterial stiffness (estimated by wide pulse pressure, carotid-femoral pulse-wave velocity, and common carotid distensibility) is a powerful predictor of incident cardiovascular events in asymptomatic individuals from the general population, patients with hypertension, subjects with impaired glucose tolerance, and patients with T2D beyond classic cardiovascular risk factors[82-84]. A systematic review of cross-sectional studies concludes that arterial stiffness is highly predictive of cardiovascular events[12]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies that followed-up 15877 subjects for a mean of 7.7 years concludes that aortic stiffness (expressed as aortic pulse-wave velocity) is a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events, cardiovascular mortality, and allcause mortality, independently of classic cardiovascular risk factors. The predictive value of increased arterial stiffness is larger in patients with higher baseline cardiovascular risk states, such as renal disease, coronary artery disease, or hypertension compared with low-risk subjects (general population)[85].

The prospective association between arterial stiffness and postmortem vascular damage was investigated among elderly subjects. There was a weak correlation between baseline arterial stiffness (pulse-wave velocity) and the degree of vascular damage observed at autopsy[86].

A large cross-sectional study with 10828 participants investigated the ability of brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity for screening cardiovascular risk in the general population. On multivariate analysis, brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity was associated with cardiovascular risk independently from conventional risk factors[87].

In a population-based cohort study in the elderly (Rotterdam study), arterial stiffness had a strong positive association with structural vascular disease. Aortic and carotid stiffness (assessed by carotid-femoral pulse-wave velocity and common carotid distensibility) was associated with carotid intima-media thickness after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors[88].

Subclinical carotid intima-media thickness predicts cardiovascular events in healthy subjects and patients with coronary artery disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that carotid intima-media thickness is a strong independent predictor of future vascular events, although data for younger individuals are limited[89]. A prospective cohort study of women shows that increased carotid intimamedia thickness predicts cardiovascular events during 7-year follow-up regardless of glucose tolerance and other cardiovascular risk factors[90]. In a systematic review,population groups with cardiovascular disease had a higher carotid intima-media thickness compared to population groups free of cardiovascular disease[55].

CONCLUSION

Numerous studies provide compelling evidence of an association between insulin resistance and subclinical cardiovascular disease that is not explained by traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypercholesterolemia or smoking. Pathogenic mechanisms underlying vascular damage linked to insulin resistance are undefined.Vascular injury associated with insulin resistance begins early in life and includes impaired vasodilation, loss of arterial distensibility, increased intima-media thickness of the arterial wall and increased arterial calcification. Subclinical vascular dysfunction associated with insulin resistance in otherwise healthy subjects is highly predictive of future cardiovascular events. Reduced vasodilation, loss of arterial distensibility, increased arterial intima-media thickness and vascular calcification in asymptomatic subjects are associated with future cardiovascular disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Ms. Gema Souto for her help during the writing of this manuscript.

World Journal of Diabetes2019年2期

World Journal of Diabetes2019年2期

- World Journal of Diabetes的其它文章

- Bilateral gangrene of fingers in a patient on empagliflozin: First case report

- SGLT-2 inhibitors in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review

- Effectiveness of royal jelly supplementation in glycemic regulation:A systematic review

- Quantities of comorbidities affects physical, but not mental health related quality of life in type 1 diabetes with confirmed polyneuropathy

- New results on the safety of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy bariatric procedure for type 2 diabetes patients