无障碍的城市空间:一个关乎所有人的话题

张利/ZHANG Li

作者单位:清华大学建筑学院/《世界建筑》

人在公共空间里行动的自主与便捷,已被认为是一种城市生活赋予人的基本权利,也已成为衡量当代城市空间质量的重要标准。这里的人指所有的人,而提升所有人的行动自主与便捷,最关键的就是尽一切可能在设计和管理上消除造成行动困难的物理障碍。

在我们一般的认识里,行动困难是和非肢体健全人群(或残障人群)联系在一起的,因而无障碍也仅仅是关乎这一特定人群的话题。但实际上,在我们的现实生活中,行动困难并不是一个持续的生理特性判定,而是一个瞬时的生理特性判定,它描述的不是一个固有状态,而是一个时间阶段——每个人在一生中都会碰到各种行动困难的时刻,其原因也大多并非是残障,而是年迈、伤病、豪饮,甚至仅仅是带着过大的箱子旅行等等这些人人都会有的经历。行动困难时每个人都会感到无助,特别依赖城市在这方面的眷顾,这也意味着,无障碍的城市空间是关乎每个人生活质量的普遍性话题。

事实上,只有抛开健全人对残障人的优越感——不再把无障碍设施看成是一种居高临下的供给,而把它看成是与自己息息相关的基础设施——无障碍的设计才能摆脱被动地满足强制性规范的状态,而真正把创造性的人文关怀融入其中。

好的无障碍设计出于对每个人的全方位呵护。每个人在城市里的行动自主一方面来源于肢体的自主,另一方面也来自于对环境信息判断的自主。无障碍设施正是在城市的各个角落对任何关乎这两方面自主的缺失,进行公共管理上的关怀和空间功能上的补偿。由DP 建筑师事务所设计的新加坡马林台组屋的快乐中心对底层架空的新加坡社会住宅进行了又一次类型学上的精细化,为老龄化的群体提供了周到的照顾。这一改造项目以“食”这一社会性的活动为载体,通过通透的界面所吸纳的光线、鲜明的色彩、高辩识度的图标、家居式的室内布设以及大家庭化的视听嗅觉氛围等,凡中生奇,为认知力降低的老人提供了真正可靠、自主与快乐的公共空间。这是一个通过设计实现广义无障碍的令人击节称快的案例。

好的无障碍设计形成于对人体自身特性的探究理解。自建筑史之初以来,缘于建筑空间与人体尺度的固有联系,对人体的不断更新的认识与研习一直是建筑学知识体演进的一个重要组成部分,从早期的静态空间尺度归纳,到其后的广义拟人化美学法则,到工业革命后的产品化设计与人体工学,再到近期的更具普遍意义的人体与社会公平。在“包容性设计”——或者用更直白的语言:服务于所有公民,一个都不能少——的理念下,“人体”的概念已不再是达芬奇或柯布西耶式的单一“完美”人体范本,而是多样化的“不完美”人体的样本合集。所谓的“一个也不能少”指向的也正是针对每一个设计问题,从其所涉及的最不利人体样本数据出发来进行决策,以保证所得的结果为尽量多的人提供便利。2018 年完成扩建的、由库珀·罗伯逊建筑事务所设计的圣路易斯拱门博物馆,严格遵循新的该国《残疾人法案》,以肢体残疾的人体为参照系,来设计从栏杆扶手到卫生间的所有细节,实现了这一颇有历史的博物馆公众可达性的全面提升。

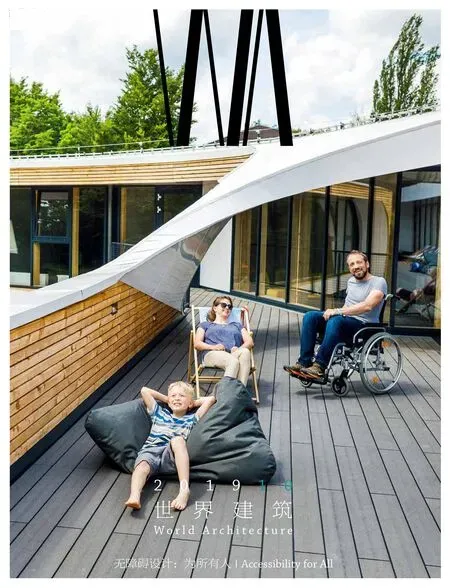

好的无障碍设计实现于物理空间中的点滴细节。今天很少有人会怀疑空间的品质取决于空间细节这一论断。当这种细节是无障碍的设计时,恐怕多数人都会认为这更多是对错的问题,不是好坏的问题,更不是创造性的问题。而当代的生活实践告诉我们,好的无障碍设计绝不是简单的对错,而是充满了对更人性化体验的想象,甚至是充满了创造性的。进入21 世纪以来,在以设计贡献于社会公平方面,斯堪的纳维亚设计为世界提供了越来越多的灵感,由AART 事务所设计的位于科瑟穆斯岛上的无障碍度假村扩建就是在无障碍领域的例证。这一洋溢着乐观主义的项目是为全球残障人士所喜爱的度假、会议与交往的理想场所。在其空间的每一个角落,无障碍的基本要素——卫生间、坡道、电梯、卧室的所有相关细部——都得到了最完备的呈现。不仅如此,在其多功能的运动与集会空间里,残障人士的体能与技巧还得到各种运动项目的挑战,其实现的方式充满着活力:不仅存在于水平的界面,如平台等,也存在于垂直的界面,比如为轮椅者使用的攀岩墙。也许我们不能说这一建筑定义了新的无障碍标准,毕竟不是所有的建筑都有足够的资源做到同样的程度,但至少它定义了新的无障碍设计的想象力边界。

正是出于以上的原因,本期《世界建筑》关注公共空间的无障碍设计,关注这一牵涉所有人生活质量的事业将如何把我们带向更加美好和更加文明的城市。

感谢中国残疾人联合会、清华大学无障碍发展研究院的专家们,是他们使本期《世界建筑》成为可能。□

The freedom and convenience of one's movement in public space has long been accepted as a basic right in modern cities. It gives a revealing measurement of the quality of an urban space. And more importantly, it address the movement of everyone, able-bodied or people with disabilities.

In traditional views, barrier-free design is only related to people with disabilities, since they are the only ones who have difficulties in autonomous movement. What a cliché it is! With a closer look, it is not hard to find out that di☆culties in movement is in fact not a statement of biological feature, but rather a statement of phase. We all meet these di☆culties at certain points of our lives, because of aging, injuries or illnesses, consumption of alcohol, or, more often, walking in an unfamiliar city with a large suitcase. We all feel the same frustrations when it becomes difficult to move around, and we are all at the mercy of the related urban facilities to get over the hurdles. Barrie-free is everyone's business.

We need truly thoughtful designs that are better than forced implementation of barrier-free building codes. We can only be creative, and humane when we are ready to give away the able-bodied disinterest and admit that barrier-free is for us all.

Excellent barrier-free designs give 360 degree care to the human body and addresses all senses. One's free movement in the city not only is a function of the level of physical autonomy of the body in question, but also is a function of the level of cognitive autonomy of the person in question. Barrier-free designs try to compensate for both wherever and whenever there is a loss or inadequacy. The Goodlife! at Marine Parade in Singapore, designed by DP Architects, is an exciting typological experiment utilising the usually featureless open ground floor of Singaporean social housing. Having the senior citizen community in mind, the design builds its entire programme around the highly social activity of eating together: the purchase, preparation, sharing and storing of food. Through a series of transparent interfaces, vibrant colour schemes, easy icons, expand-family styled layout and the capture of smells and sounds, the project gives something that is truly extraordinary to a very generic typology: convincingly good life for the aged.

Excellent barrier-free designs come from deeper understanding of the human body. The human body has been both a hot topic of debate and a driving force of knowledge renewal throughout the history of architecture, not surprising at all considering the inherent bond between the built environment and human scale. From the early principles on dimensions, to the general rules of anthropomorphism proportions, to ergonomics, to the contemporary idea of human body as a field of social equality. Inclusive design of our time no longer takes the human body ideals - those of Da Vinci or Le Corbusier - as the one exclusive archetype of human body. On the contrary, it embraces all samples and all types of human bodies, perfect or imperfect, abled or disabled. Under the idea of public space for every-body, detailed design decisions are usually made taking the least abled body as the reference. Cooper Robertson's Expansion to the Gateway Arch Museum in St Louis was determined to deliver an exemplary public service from the starting point of the design. Completed in 2018, it meets or exceeds all the requirements of the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act). A complete set of building details, from the railings to the bathroom handles, showcase decades of research and engineering focused on bodies with disabilities.

Excellent designs materialise in details. Everyone nowadays would agree that quality comes from details. But when it comes to the details of barrierfree, most would take for granted that it is more a question of efficiency, rather than quality, let alone creativity. Yet there are cases that demonstrate otherwise. We all know how Scandinavian design has become a source of inspiration in design for social equality in the 21st century. In the field of barrierfree design the same statement holds. The expand Musholm in Korsør, designed by AART architects, is nothing short of inspirational. It is not only a resort for people with disabilities, but a place that celebrate courage and optimism. All the necessary elements of barrier-free, from details in the bathrooms, ramps, lifts to those in the bedrooms are done with great care. More importantly, its generous sports hall challenges the bodies of those with disabilities with vibrancy and rigour through the creative design of playground, paths, and an incredible rock climbing wall for wheelchairs. Probably it is too early to say whether the Musholm has indicated the underlying profile of the future standard for barrier-free design, but it certainly has indicated a new boundary of design imaginations and creativity.

It is for the reasons above that we publish this number of WA on barrier-free designs. We are keen to learn how barrier-free design is making, and will continue to make, everyone's life a little bit better.

Our sincere thanks to experts from China Disabled Persons' Federation and Institute for Accessibility Development Tsinghua University. They have made this special number of WA possible.□