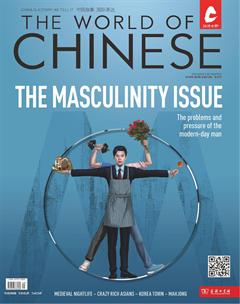

MAN TROUBLE

谭云飞

Attitudes toward gender, dating, and marriage are in frequent flux. Some men welcome the changing times. Others fear for the future. Those who once enjoyed unassailable positions of power now risk being called out for abusive or harassing behavior. At school, boys are falling behind with their grades amid fears of a growing “masculinity crisis,” the result, some claim, of over-parenting and feminized education. In the workplace, men are frequently competing for pay raises and seniority; while at home, the pressure is on for first-time fathers to be “wonder dads”—patriarchs who dont just bring home the bacon, but cook it, and help with the washing up and homework afterward. Is this why, as some polls report, increasing numbers are indulging in affairs? In this issue, we look at whether Chinese men are truly in crisis—or if the boys are actually doing alright.

男人好難:父亲和丈夫的角色正在被社会重新定义,还有人认为

“男孩危机”正在学校中蔓延,在传统和现代观念交织的今天,

做一个男人没有那么简单

BOYS WONT BE BOYS

Are educators and pop idols to blame for Chinas alleged “masculinity crisis?”

S

ave the children,” writer Lu Xun famously concluded his classic 1917 short story “Diary of a Madman.” A century later, some believe that its boys, especially, who need to be saved.

In 2010, writer and educator Sun Yunxiao published his bestselling Save the Boys, in which Sun, together with two child psychologists, claimed that the countrys young men are experiencing a “boys crisis”—not only falling behind girls in academic performance, but also becoming increasingly emasculated.

Since national university entrance examinations (gaokao) were re-introduced 40 years ago, boys have accounted for 56 percent of the top scorers among Chinas 31 provinces. However, according to statistics published in 2017 by Cuaa.net, that proportion has decreased to 47 percent over the last decade. Sun says this decline is reflected across the board, from school exams to achievements in university. In 2012, the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences produced research showing that gender disparities in academic achievement can emerge as early as the third grade.

Sun in Save the Boys imputes this to Chinas examination-oriented education system. “Teachers like well-behaved students. But boys are rebellious by nature, so they are very likely to be removed from the list of ‘good students,” he writes.

Sun also blames an ignorance about basic biological differences between boys and girls, claiming that their brains develop at different speeds. Allegedly, primary school boys develop verbal and written language skills more slowly than their female peers, but these abilities happen to be emphasized more in the current evaluation criteria. “Our examination-oriented education is unfavorable for both boys and girls,” Sun writes, “but compared to girls, boys suffer more.”

Sun is far from the first modern educator to sound the alarm on behalf of boys, nor the first to suggest rigging the results in their favor. In 2005, the foreign languages department of Peking University reportedly admitted boys with a lower minimum score, while Jilin University professor Yu Changmin admitted that their College of Foreign Languages often found excuses to eliminate female applicants, because they far outnumbered male applicants.

Suns plea still hit a nerve, though. After its publication, the China Foreign Affairs University told Sohu that they planned to lower admission standards for boys; in 2012, both Renmin University and the Shanghai International Studies University lowered the bar for male enrollment in order to maintain a “reasonable” gender ratio.

By 2016, Zhu Xiaojin, vice-president of Nanjing Normal University and Chinese Peoples Consultative Conference member, was proposing a national solution: allowing boys to delay primary school for two years while they “liberate their natures, enjoy playing, and sharpen their thinking ability,” so that “when they enter school…they wont be defeated at the starting line.”

Opponents argue its unfair to pander to one genders lackluster performance. “Why cant girls score higher than boys?” asks Li Yichen, a teacher at the Affiliated High School of Peking University, who has a masters degree in gender studies. “So many fields are dominated by men, and no one feels its a problem. Now that girls score a little higher in exams, it becomes a problem?”

“The logic behind [Suns book] is, any field in which women outperform men is meaningless,” Li adds, “and any system that allows women to have advantages over men is flawed.”

But examinations are not the only criteria in which boys are not measuring up. An alleged “crisis of masculinity” is also troubling some educators. “I wonder whether boys or men are less masculine today,” primary schoolteacher Feng Lina tells TWOC. In her classroom in Kaiyuan, Liaoning province, she observes that “[boys] are less chivalrous in front of girls, less willing to take part in work, and tend to hold back when something happens.”

Feng is not alone in her opinions. An informal TWOC survey of 15 kindergarten, primary and middle school teachers asked the question “Do you think boys today are less masculine than before?” Fourteen answered “Yes.”

Since 1896, when the North China Daily News coined the disparaging term “Sick Man of East Asia,” Chinese men have often been condemned for physical weakness. After the one-child policy was introduced in the 1980s, a preference for male heirs gave rise to the nickname “little emperors” for pampered only children.

Fawning parents were criticized for rearing a generation of coddled male good-for-nothings; the term “4-2-1” syndrome described four doting grandparents and two overindulgent parents, all pinning their hopes on one child. “We all say todays boys are more pampered than before. Many of them are afraid to take risks,” says Wang Peng, a kindergarten teacher who works with Feng.

“Their looks and dressing style are also becoming effeminate, maybe influenced by Japanese and Korean pop stars,” adds Lü Na, Wangs co-worker. Save the Boys takes direct aim at the aesthetics of delicate male stars, now known as “little fresh meat” (小鮮肉). Sun had scoffed that “so-called ‘androgyny is more about boys being effeminate, which can cause far-reaching harm.”

Within the film industry, screenwriter Wang Hailin (The Assassins, Murder at Honeymoon Hotel) expressed similar concerns. “Male actors represent national ideology,” Wang said at a recent press conference. “If the most popular male actors in our country are the most feminine-looking ones, it will threaten our national aesthetics.”

Li strongly objects to such old-fashioned standards, “The subtext is: Masculine qualities are good, so its fine for a girl to be ‘manly, but feminine qualities are bad, so men cant have them.”

Professor Zhang Meimei, who works at Capital Normal Universitys Education Department, believes the “crisis” is a sign of the times. “Todays women are more and more dominant, which makes men seem shyer and more introverted,” Zhang said in an interview with Xinhua. “The second reason is, the mother usually plays the role of educator in the family, which makes boys more influenced by femininity.”

This is compounded, Sun believes, by a lack of male role models in the classroom. “Children need both female and male teachers for their development,” Sun told media start-up Sixth Tone, explaining that the shortage of male teachers at school has a negative influence.

While there is no evidence to suggest that male teachers are more beneficial for boys, some educational institutions have already taken action. According to the Beijing News, at least five provinces—Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Fujian, Hunan, and Sichuan—now offer free teacher-training courses for men to attract more males to the profession. In 2016, an elementary school in Wuhan set up a “male teachers workshop,” in which “man-to-man dialogues” were regularly held between boys and male mentors.

The same year, a Nanjing middle school established a “boys education and activity class,” providing extra physical training for male students by male teachers. Another “all-boys” class at a Shanghai middle school even exclusively introduced special “manly” subjects, such as martial arts, Chinese chess, and rock music. Little Men, a textbook purportedly teaching primary school boys how to be men, has become part of the curriculum in many schools.

However, Li feels much of the response has been in the wrong direction. “I think good education should teach that, no matter if you are male or female, you dont have to follow the traditional dictates of your gender,” says Li. “Anything that you ‘have to do, due to the conditions you were born with, is against the universal values of freedom and equality.”

- SUN JIAHUI (孙佳慧)

DADDY ISSUES

With “wonder dads” becoming the new face of Chinese families, many fear extra pressures on already fragile fathers

T

here was no doubt that 21-year-old “Katie” (pseudonym) was the apple of her fathers eye. No one else would dream of touching the provincial party secretary—let alone playing with the leaders “ears that catch the wind,” as Katie teasingly described them.

Their tenderhearted exchanges in a restaurant elevator in Katies hometown challenged old-fashioned values as much as they embraced familial ones—when the doors opened, to the public eye, both jumped back into their formal roles. For centuries, Confucian and later Manchu mores dictated parent-child relationships. The quintessential Chinese father was the benevolent patriarch, provider, and head of the household; austere disciplinarian tendencies ensured that “strict father and benevolent mother” (嚴父慈母) was the largely accepted family model.

While far from extinct, this rigid role has several new challengers in todays more pluralist environment. For many modern fathers, it is not enough to merely bring home the bacon. They also need to be emotionally—and literally—available: the type of father who gets a “#1 Dad” coffee mug for Fathers Day (and deserves it).

But this expanded ideal is often accompanied by increased obligations, financial and otherwise, meaning these new dads are not just “better,” but oftentimes more insecure. Beijinger Mr. Mao fears that he falls short of being the perfect father to his 4-year-old son. The ideal dad should “provide his children with the most resources he can, as well as invest as much time and energy as he can into the children and the home,” the 38-year-old father told TWOC.

Mao is not alone in his thinking: A fatherhood study conducted by PR firm J. Walter Thompson Intelligence (JWT) found that 60 percent of Chinese fathers did not feel they had enough time to spend with their children, while 95 percent had difficulties balancing careers with home life. Hoping to bolster values that encourage couples to have a second child, several provincial governments have offered benefits to new fathers: In 2017, Jiangsu followed the footsteps of Gansu, Henan, and Yunnan provinces by establishing a

30-day paternity leave.

Bucking familiar trends, the JWT study also revealed that a significant percentage (48) of fathers believed that helping with homework was their primary responsibility, just ahead of entertaining and playing with their children (though only 16 percent thought they should take on diaper duties).

Companies have taken notice of middle-class daddy issues and are bent on turning them into a consumerist trend. In 2016, Bayer started a campaign for Elevit prenatal vitamins in China, in which fathers heard their unborns heartbeats for the first time; the ad quickly became one of the top trending topics on Weibo. In July, BMW released “Wonder Dads,” a 15-minute video featuring movie stars Mark Zhao and Song Jia, in which a young boy imagines his reliable, lower-level executive Shanghai father as a superhero (driving a BMW X3, naturally).

But it was Hunan Televisions 2013 reality hit, “Where Are We Going, Dad?” (《爸爸去哪兒?》), that catapulted modern fathers into the mainstream. Featuring celebrity dads taking their preschool-aged children on countryside adventures, the program quickly became one of Chinas most popular shows, with 75 million viewers per episode, and support from China Daily for promoting a “return to family values.”

While fatherhood has been in flux for over a century, it was during the reform era that the concept began to change dramatically, according to Xuan Li, Assistant Professor of Psychology at the Shanghai branch of New York University.

In post-1980s China, the 拼爹 (p~ndi8) phenomenon—meaning “compete using father,” the practice of leveraging a parents status to improve ones own—proliferated. Many privileged youngsters launched lucrative careers not on their own merits, but rather the reputation, connections, and capital of their fathers. This created immense pressure for Chinese men, in particular, to ensure opportunities for not only themselves, but also their offspring in Chinas increasingly cutthroat capitalist economy.

Additionally, as socialist influences waned, women found themselves increasingly forced out of the workplace and back into home. While still the largest in the world, Chinas female workforce is steadily declining—from 73 percent in 1990 to 61 percent in 2017. Subsequently, todays fathers “feel more pressured in the rat race to provide financial, social, and cultural capital for their children,” Xuan told TWOC, which was not the case when women were co-breadwinners.

Reform led to not only economic, but also cultural changes. Western media provided new examples of how fathers could engage with their children. Mao says that his parenting style is quite different from that of his father: “For people born in the 1970s and 1980s, we have felt strong influence from Western culture. Now, on top of being a traditional father, we should also be friends with our children.”

Xuan agrees that Western media has introduced new models for parent-child engagement which focus on “greater warmth, affection, and equality between parent and child.” In her research, she also states that the impact of the one-child policy, which accompanied the economic reforms, cannot be ignored. As parents focused on the well-being of their only child, some began to criticize traditional parenting models, including Confucian austerity, in favor of emotional connections with their children.

Others, though, have bunkered down deeper into Confucian tradition, earning the title of “tiger” or “wolf fathers.” Chinese media have showcased examples such as Zhang Yu, a Sichuan father who forced his 6-year-old son to conduct intense training exercises every day, as well as down two bottles of beer, and Nanjings He Liesheng, who trained his 9-year-old son to climb Mount Fuji and singlehandedly fly an airplane. Meanwhile, 7-year-old piano prodigy Chen Ankes success is often attributed to her fathers “tiger” tendencies.

On the other hand, China has a substantial male population without the financial and social resources, let alone time, to achieve the elusive “wonder dad” status. Xuans research notes that a “fathers education level is a significant determinant of [his] expression of warmth and affection.” In a countryside littered with tens of millions of “left-behind children,” whose parents migrated to work full-time in urban centers, new fatherhood models create another set of unattainable values that exacerbate the urban-rural divides in wealth and culture.

In the meantime, middle-class Chinese fathers are playing a game of constant catch-up to meet ever-increasing standards depicted by an oftentimes-unrealistic media. In August, Mercedes debuted its latest advertisement depicting a father rushing home from work to give his young son a toy bear. It was a campaign played relentlessly in elevators in office buildings across Chinas business districts, to an audience of stressed white-collar workers unlikely to have enjoyed such magically materialist childhoods themselves—yet still expected to provide one. - EMILY CONRAD

WHAT WOMEN WANT

Drawing from recent reportage, surveys, polls, and our own observations, The World of Chinese presents some of the most desirable types of Chinese man—plus a few stereotypes women would like to do without.

The Overachiever 學霸

He might not be the most handsome or charismatic guy, but he is super smart. Who knows? Maybe he might end up the next head of Baidu, like Robin Li! (But hopefully not the next Richard Liu, the JD.com chief recently arrested for sexual assault).

A generation ago, the overachievers would have probably ended up on a farm or factory line, but now he tests so well in the gaokao that he earned a place at one of Chinas top universities, the alma maters of several members of the Politburo.

After graduation, he either went straight into a high-paying job in the IT or financial sector, or is still pursuing his masters or PhD. Confucian ethics run deep and education is still a measure of a mans worth, so he will instantly win the approval of prospective parents-in-law.

Economic Man 经济适用男

Named after the governments affordable housing program, the “Economic and Applicable Man” concept is a simple one: Just as not everyone can afford their ideal apartment, not everyone can end up with the man of their dreams. Therefore, a single woman should strive to be practical when it comes to finding a husband—at least, according to the 2010 book Marry an Affordable Man.

The “Economic Man” is an average-looking guy with a gentle personality and traditional values. He has a stable job and gives all his salary to his wife. He never smokes, drinks, or gambles, nor has any “dangerous” female friends. He takes care of the family and is filial to his in-laws. He may not make anyones heart race, but at least you know you will have a stable life with Mr. Economic.

Warm Man 暖男

Being with a “warm man” is comparable to enjoying a warm spring day. A warm man cares deeply and devotedly. He listens to women and seems to understand. But make sure hes not a “central air conditioner,” which means hes nice to everyone, not just you. A warm man cooks for you and does the housework; he gives you a foot massage after a long day; he packs an extra sweater in your purse because its cold outside; hes like your favorite unpaid butler. Warm men arent always the richest or the most handsome, but they put you first.

Civil Servant 公务员

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man holding a government position must be in want of a wife. An “iron-rice bowl” job is still a plus in the marriage market, especially in smaller cities. For some parents, an eligible civil servant is the ideal match for their daughters: He belongs in the system and will probably never lose his job. Sure, his income is average, but who knows how many hidden “perks” he receives?

If finding a partner is all about careful screening, the civil servant is not a bad choice—after all, over two million people took the civil servant exam last year and only one-sixteenth passed.

STATE OF AFFAIRS

Rocketing divorce rates have alarmed the government—is a culture of infidelity

to blame?

L

ily (pseudonym) did not think twice about when a family friends colleague offered to drive her home after dinner. He was sober, her place was on the way, and, besides, her friend was a powerful guy. No one would want to upset him.

Their conversation was innocent enough, as they discussed how his 10-year-old son should study to attend a top university like her. But when they arrived, he leaned over to forcibly kiss her. For weeks afterwards, he continuously texted her, asking her out to dinners, clubs, and KTVs before finally taking the hint to stop.

Theres nothing unusual about a story like Lilys. The private lives of many married men are filled with mistresses, mystery girlfriends, and KTV visits, if rumors and reports are to believed. Renmin Universitys Professor Pan Suiming, a specialist on Chinese sex lives, has estimated that 34.8 percent of men had engaged in sexual relations outside of marriage—a conservative figure. An online poll by Tencent had the number even higher, at 60 percent (and thats just those who admit it).

The issue is prevalent enough to have spawned a minor industry, devoted to providing solutions to the problem of having an unwanted “little third” (小三) in your life, as mistresses are often called. Teams of expensive experts—known as “mistress dispellers”—claim to offer wives tips and makeover advice to reclaim their wandering spouses, while promising to ward off mistresses with a range of dubious tactics like bribery and threats.

Anthropologist John Osburg is not surprised by these studies. During research for his 2013 book, Anxious Wealth: Money and Morality Among Chinas New Rich, the associate professor of anthropology at the University of Rochester befriended and interviewed numerous wealthy businessmen in southwest Sichuan province. “The infidelity rate of my research subjects was nearly 100 percent,” he told TWOC. “Of course, my sample size was relatively small and the subjects had a lot of similarities.”

Although infidelity is nothing new in society, the issue has gained public attention in recent years in part due to Chinas skyrocketing divorce rate, which has doubled in the last decade, with many citing extramarital affairs as the cause. In 2017, a representative of the Beijing No. 2 Intermediate Peoples Court told the South China Morning Post that 93 percent of divorces stemmed from either affairs or domestic violence.

In an attempt to clamp down on divorce and promote “traditional family values,” the government is introducing a “cooling off” for couples seeking separation, during which they are encouraged to reconcile their differences through counseling. Parental pressure may also have helped preserve unhappy marriages in the past—but, according to Beijing marriage counselor Li Kening, who has worked for over nine years in the suburban Tongzhou district, the situation is quite different today.

“Some young couples are actually being pressured to divorce by their parents,” Li told TWOC. “If a womans parents hear that her husband has had an affair, or is not treating her right, they may tell her to seek a divorce. Likewise, mothers of

媽宝男 (mommys boys) find constant fault with their daughters-in-law—even divorceable faults.”

Beijinger Mr. Zheng agrees. Believing that city life makes people more liberal, he isnt pushing his 31-year-old son into marriage, preferring him to find a woman with whom he has emotional and physical chemistry. However, “If my son fell in love with another woman and wanted to leave his wife, I would advise him to work harder to make his first marriage work; if I couldnt persuade him, I would support his decision to divorce,” Zheng said. “I am Chinese, and it is still important to keep the family tradition.”

While the one-child policy has undoubtedly elevated the importance of their childs personal fulfillment and happiness in parents minds, Osburgs research provides other insights. One major reason that Osburgs research subjects did not pursue divorce was peer—rather than family—pressure. He cited the case of a businessman who fell in love with a nightclub dancer, but ultimately decided to stay with his wife, out of concern for how his business associates and peers would view such a partner, or judge his character and sense of familial responsibility.

On the other hand, Osburg noted, his subjects seemed to be happier—and more “in love”—with their mistresses than their wives. The 1950 Marriage Law, which abolished arranged marriages, was not quite the societal game-changer it first appeared. Class differences were a perennial obstacle, tradition another: Parents still had a great deal of say in their childrens affairs, matchmaking remained prevalent behind the scenes, and there was virtually no dating culture. Marriages and divorces even needed approval by each partners work unit.

Influenced by new models of romance and partnership in Hollywood movies and Cantopop in the reform era, young people wanted to marry for love, although many did not know how. Osburg says his subjects often talked about fatherhood, and their pride in their children, but rarely their satisfaction with marriage. Instead, they lamented their lack of experience, or their innocence at the time of their marriages. “I went out with [a woman] and everybody started talking about us getting married, so we did” was a typical refrain.

And while reform brought back romance, it also marked out new inequalities. While ancient concubine culture usually came alongside a moral justification—getting male heirs to continue the family line—in addition to status-signaling for elite men, Osburg states that the wealth gap has exacerbated gender inequality, creating a ready supply of young women willing to become mistresses for material gain. His subjects lament that some women now throw themselves at wealthy men, hoping that an affair would provide them with financial support—or, as the saying goes, “A man goes bad when he gets rich, a woman goes bad to get rich.”

As for men, mistresses can be a status symbol, especially as the gender disparity caused by the one-child policy has made women a rarer “commodity.” Tencents survey suggests that men with higher incomes are more likely to cheat, and that IT, finance, and education are the most adulterous professions. Osburg observes that many of his subjects work long hours outside of the home, and some worry about being considered prudish if they do not join business partners and colleagues in bonding activities involving alcohol and prostitutes. Then, there are those who rationalize infidelity as thats just how men are.

However, Li notes that adultery is is now no longer the preserve of the wealthy. “It used to be that to keep a mistress, you needed to be rich,” he tells TWOC.“With the rising use of social media, we are starting to see lots of people pursuing one-night stands, many of which can bloom into a full-on affairs.”

As divorce becomes less taboo, dating culture more prevalent, and parents less able to exert control over their childrens love lives, both sexes are finding more opportunities to pursue their ideal life partner—which may, in the end, have a positive influence on reducing infidelity. Theres even hope for the current “divorce generation,” Li suggests: “People can learn from their failed marriages and better prepare for their next one.”

- EMILY CONRAD

Additional reporting by Tan Yunfei (譚云飞)

WHAT WOMEN

Dont Want

Greasy Guy 油腻男

If hes toting a clunky gold neck-chain, prayer beads, and a hot-water flask filled with red dates and goji berries—be careful, this man might be youni (“greasy”). If he favors wearing long johns around the house under a bulging gut, though, its probably already too late.

The weisuonan (猥琐男 “sleazy man”) has been around for decades, blissfully unaware of his own creepiness. Perhaps the recent rise of the less alarming mans counterpart—the overly primped “little fresh meat”—prompted the need to rename this familiar figure.

Aging writer Feng Tang, who popularized the plight of the youni in a 2017 essay, “How to Avoid Becoming a Greasy, Dirty Middle-Aged Man,” offered a number of pointers to avoid greasiness: “Never talk down to the younger generation”; “Never stop buying.” Unfortunately, these have been mocked as being precisely the things a weisuonan would do, such as humble-bragging and trying to appear “down” with millennials.

Age is no barrier to being a greaseball—overly confident young actors like Yang Yang and Yang Shuo are regularly accused of greasiness—nor is gender: Gossipy older women who obsess about yoga, cosmetics, and the need for a better apartment also belong in the grease bucket.

Phoenix Man 鳳凰男

Surveys on dating sites consistently suggest one of the least popular stereotypes is the self-made or “phoenix” man. Referring to the idea of “a phoenix that soars out of a chicken coop,” this is an ordinary man who grew up in the countryside, but worked tirelessly to get a good gaokao result and perhaps eventually a high-level executive position in the city. So why is the destiny-changing phoenix man not respected for his hard work and enterprising nature?

The answer lies in his rural roots—which make him particularly unpopular with middle-class urban “peacock girls” (孔雀女). The idea, depicted in TV shows like Double Sided Adhesive Tape and New Marriage Age, is that the “phoenix” will have exhausted his entire familys finances in his quest for upward mobility; in turn, the family will have pinned all their hopes on his success, and expect him to provide for them. The phoenix man will therefore prioritize the needs of his extended family over his partner, who will be expected to comply with the familys customs, culture, controlling ways, and demands for money. Urban parents may find their rural in-laws irritating and unsophisticated, or fear that their daughter will end up acting as her new familys unpaid servant.

In addition, phoenix men are accused of having a range of insecurities, such as being controlling over their wives social life and friends, fear of failure, and being miserly about money due to having grown up poor.

SINGLE AND SCARY

Sedition, sexuality, sorcery, and seduction were among many anxieties that the Qing associated with unmarried men

It was high summer in Anhui province, when Wang Yuzhi found himself both alone and drunk. By his own confession, Wang had lusted after the 18-year-old wife of his neighbor, Li Guohan, for months. That night, emboldened by alcohol, he decided to take action.

Creeping up to the couples hut, Wang used his knife to dig through the earthen wall, slithered in, and attacked Lis wife as she slept naked. Realizing the interloper was a stranger, she fought back, managing to bite off part of Wangs tongue. When the couple reported the attack to the local magistrate, they presented the gory tip as evidence. For the crime of forcible rape,

Wang was executed by strangulation in 1762.

Wang Yuzhi was a 光棍兒 (gu`ngg&nr;), or “bare branch,” a term for a man without a spouse or prospects, nor hope of finding either. Chinese society is rooted in family, but as many as one in four men in 18th-century China were unmarried, a number that increased dramatically the lower one looked on the socio-economic ladder, or the further away from a city or town. Wangs case, described by Matthew Sommer in Sex, Law, and Society in Late Imperial China (2000), was typical of what Sommer, and historians including Thomas Buoye and Vivien Ng, describe as the anxieties that lifelong bachelorhood provoked in Chinese society.

Concerns about guanggunr would prove a fundamental part of the legal and popular discourse on gender in the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911). The 18th century was a time of great prosperity for the Manchu empire, a stability that brought population growth. As the population doubled to almost 300 million, demographic challenges ensued. A societal preference for boys ensured a surplus of marriageable men. Polygamy among the elite and a tradition of women “marrying up” (but rarely down) meant fewer potential brides for men at the bottom rungs of society. This growing underclass became a constant source of concern.

Frustrated guanggunr were viewed as potential predators, capable of polluting both men and women. Officials were wary that men with nothing to lose might constitute a criminal class. Guanggunr made up the bulk of arrests for rapes, murders, and kidnappings. During the “sorcery scare” of 1768—involving allegations that masons were harvesting mens ponytails for supernatural purposes, as detailed in Philip Kuhns Soulstealers—the main suspects were identified as guanggunr. The Qing court eyed roving bands of rootless young men as potential fodder for rebellious movements.

As is too often the case, women suffered for the anxieties of their husbands, brothers, and fathers. Female purity became synonymous with social order; to defend one was to uphold the other. A series of Qing laws narrowed the definition of legitimate sexual contact to solely the penetration of a wife by her husband; another series of edicts stiffened penalties for rape and illicit sex—which could include almost any physical contact outside of marriage. But proving rape relied heavily on the status of a womans fidelity, with her virtue usually demonstrated by how forcefully she resisted her attacker.

As historian Vivien Ng notes, “The price of chastity was very high indeed. It was worth at least one life—that of the rapist. Sometimes it exacted two lives—that of the victim as well.” It was assumed that a woman should prevent an attacker from penetrating her—or, at the very least, die trying. (In fact, the death or significant dismemberment of the victim was often required to get a conviction for rape; or, as in Wang Yuzhis case, the maiming of the attacker). Anyone with an “illicit” sexual past could disqualify themselves as a victim (male prostitutes could also forget about getting a fair hearing). Moreover, consent, once given, could not be rescinded and there was no concept of “marital rape.”

Women “stood on the frontlines to defend the normative family order, and the standards of chastity would determine its fate,” argues Sommers. Conversely, “through promiscuity and sloth, they might destroy it.” Far from repressing women, though, Sommers argues that Qing law actually strengthened their position, protecting the family from downward mobility of the guanggunr underclass.

But the laws strict emphasis on defining “coercion” clearly reflected a male anxiety: the fear of nymphomania, the concern that a woman might be complicit in deviant sexual behavior. Those who enjoyed legal access to a womans sexual favors welcomed increasingly stricter penalties to protect against their displacement.

The idea of unmarried vagabonds as being a threat to the social and political order is not limited to history. Contemporary China faces its own gender imbalance. Census data suggests that there may be as many as 34 million surplus males—almost the entire population of California, or Poland—doomed to perpetual singledom.

As in the Qing era, these gender ratios skew ever more heavily male the further one descends on the socio-economic ladder or travels out into the countryside. Involuntarily celibate in a society which prizes the family unit, Chinas leftover men are once again a cause for official concern and popular anxiety; a 2012 report from the Institute for Population and Development Studies warned that rural guanggunr were more prone to rape, incest, wife sharing, unsafe sex, human trafficking, and homosexuality. Authorities fret about criminality while international observers grow uneasy about the possibility that frustrated young men could fuel an increasingly aggressive and aggrieved nationalism.

Whether real or imagined, the fear of the guanggunr is a grim reminder that prosperity comes with its own costs. For the Qing, demographic pressures and stress on available resources began to overwhelm the states ability to maintain social order in the 19th century. Nearly a century after that hot and terrible night in Anhui, young men like Wang Yuzhi would be tinder for the spark of rebellion during the Taiping War and Nian Rebellion. Demographics may not be destiny, but the specter of the guanggunr over 18th century China proved one of many ill omens for the century which lay ahead. - JEREMIAH JENNE

ANCIENT IDEALS

While the modern male ideal ranges from successful businessman to family guy, the epitome of ancient Chinese masculinity was more specific—a junzi (君子, “superior man”). The term originally described a nobleman—literally, “son of a lord”— during the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 BCE – 771 BCE), but later described virtuous men who fulfilled Confucian obligations.

While still one rank below the supreme honor of sage, ancient junzi were the epitome of both high morals and talent. Late Qing dynasty scholar Gu Hongming (辜鴻铭) believed that the essence of Confuciuss philosophy was “the doctrine of junzi.” A junzi possesses the virtues of benevolence

(仁), righteousness (义), propriety (礼), knowledge (智), and integrity (信), and follows the tenets of loyalty (忠), filial piety (孝), and honesty (廉). In his Analects, Confucius mentions junzi 107 times (referring to rulers in a dozen instances) and its opposite, xiaoren (小人, “inferior person”), 24 times, claiming “The mind of the superior man is conversant with righteousness; the mind of the mean man is conversant with gain” (君子喻于义,小人喻于利). Since the Zhou dynasty, students were encouraged to become junzi by mastering the “six arts” (六艺): rites, music, archery, charioteering, calligraphy, and mathematics.

- TAN YUNFEI

JUNZI DOS AND DONTS

· Do honor your father and mother

· Dont borrow your fathers horse without asking

· Do maintain a prosperous and harmonious

household

· Dont spend all your time with the concubines

· Do obey the emperor

· Dont agree with everything he suggests, then

switch sides when the dynasty falls