Determinants of cooperative pig farmers’ safe production behaviour in China – Evidences from perspective of cooperatives’ services

JI Chen, CHEN Qin, Jacques Trienekens, WANG Hai-tao

1 Department of Agricultural Economics and Management, School of Public Affairs/China Academy for Rural Development (CARD),Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, P.R.China

2 Business Management & Organisation, Social Sciences Department, Wageningen University Box 8130 6700 EW Wageningen,the Netherlands

3 School of Economics, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei 230601, P.R.China

Abstract Farmers’ production behaviour is a key to ensuring the safety and quality of their final products, and cooperatives play an important role in shaping that behaviour. This paper aims to explore the determinants of pig farmers’ safe production behaviour, giving special focus from the perspective of cooperatives’ services. This study adopted cross sectional survey data from 27 pig cooperatives and their 540 farmers in China to test the influence of cooperatives’ services on farmers’ safe production behaviour. The hypotheses were tested using a logit regression model. The findings indicated that although the number of services is not a key determinant of farmers’ safe production behaviour, service quality matters. When a cooperative is strongly capable of involving more farmers in certain services, and provides certain services in more frequency, member farmers behave more safely. The results also show that veterinarian and pig-selling services play an important role in ensuring farmers’ safe production behaviour. For this study, the quality of cooperatives’ services is implied to have a positive impact on farmers’ safe production behaviour. Leaders/managers of cooperatives must try to improve the quality of their services instead of merely attempting to provide a large number of services. For government officials and policy makers, designing policies that encourage cooperatives to improve their service quality is important. This research contributes to the scant literature on how cooperative services could help farmers engage in safer production behaviour,which would improve the safety of pork products in the future.

Keywords: farmers’ safe production behaviour, pig sector, farmer cooperative, China

1. Introduction

The pig industry plays a dominant role in China’s livestock sector. Despite the increasing political and public attention on food safety issues, pork safety incidents (including many high-profile scandals) have occurred frequently over the past 10 years, and pork safety remains a major concern for Chinese consumers. How pigs are raised is the primary factor that influences pork’s safety and quality. Pig production is an extremely comprehensive process that includes feeding, breeding, vaccinating, using veterinarians and ensuring that production waste is disposed of. Behaviours violating the best practices of any of these tasks may increase the safety risks of pork. Pig production in China is dominated by small pig producers; however,the entire industry is reorganizing, and scaled farming is increasing. Ensuring pig production safety is an issue of great significance but remains a challenging problem to address.

While cooperatives have played an active role for a long time in many countries in agricultural sector (Hansmann 1996; EU commission 2009), development of cooperatives in China is in the first stage of development and face numerous problems and challenges (Xu et al. 2013). However,cooperatives have increasingly played an important role in agri-food industries and supply chain as it connects and coordinates farmers, intermediaries and companies.Chinese government has encouraged the development of cooperatives since 2007 considering that cooperatives could help farmers to reduce inputs cost, enhance market linkage and bargaining power, improve production skills and shield from risks (Nilsson 1998; Xu et al. 2013).Chaddad and Cook (2004) etymologized new cooperative models from ownership-control rights perspective under the background of agricultural industrialization. And follow this perspective we find that cooperatives in China are mainly categorized into two types in terms of the ownership, which are farmers-owned cooperatives (traditional cooperativestructure in line with ICA (International Cooperative Alliance)definition), and investor-owned-firms (IOF)-led cooperatives(“IOF+cooperative+farmer”, an innovative cooperative form in China). IOF-led cooperatives is considered as playing important roles in helping farmers enter big markets as well as the system of agricultural industrialization, and farmers-owned cooperatives will lead the way to market terminal for small farmers (Xu et al. 2013). In pig industry in China, traditional farmers-led cooperatives vary in terms of cooperative size, ownership and control, while IOF-led cooperatives vary in terms of the core business of the leading company (e.g., feed company-led, pig production company-led, slaughterhouse company-led and verticallyintegrated company led ones), governance structure and ownership.

Although the behaviour and economic performance of cooperatives has been the focus of extensive theoretical and empirical research, the issue of product quality has received relatively little attention in these studies (Pennerstorfer and Weiss 2013). While some scholars found that cooperatives play a central role in food safety management and provide premium quality compared with non-cooperative farmers(Jin and Zhou 2011; Zhou et al. 2015; Kirezieva et al. 2016),the influence of cooperatives on food quality and safety assurance is an on-going debate. Several studies showed that cooperatives provide more support activities to their members and therefore deliver better and more uniform quality than investor-owned companies (Balbach 1998;Cechin et al. 2013), others, however, claim that cooperatives provide lower quality products than IOFs or publicly listed firms (Cook 1995; Liang and Hendrikse 2016).

Cooperatives are shown to play a central role in food safety management, and current research mainly focuses on the adoption of safety standards by cooperatives at the institutional level (Kirezieva et al. 2016). However, Van Hoi et al. (2009) indicated that the product quality offered by a cooperative is largely dependent on individual farmers,while empirical evidence regarding how cooperatives can shape individual farmers’ safe production behaviour is rare.

We review related studies and propose that cooperatives influence their member farmers’ production behaviour via the services they provide. Moustier et al. (2010) found that collective action by farmers plays a crucial role in promoting quality, primarily because it facilitates access to training resources. Emerging forms of agribusiness have begun to view cooperatives as a viable channel for introducing technologies to farmers and thus for maintaining food quality by using contracts (Guo et al. 2007; Jia and Huang 2011).Although current studies have not clearly stated that the services offered by a cooperative may influence its member farmers’ safe production behaviour, all the facts overviewed in this paragraph are directly related to cooperative services.

Based on existing literature (Huang and Gao 2012;Wang 2017) and our field studies, we identified seven functions related to product safety that are provided by pig cooperatives in China, including feed purchases, breed purchases, veterinarian services, vaccination purchases,live pig sales, professional training, and capital credit support. Cooperatives in China are different in terms of their service numbers. For example, some cooperatives provide only one or two services of the seven mentioned, and some cooperatives offer six to seven services. Apart from the difference in the numbers of services provided, cooperatives’service quality varies considerably. Service qualities of the cooperatives describe how well cooperatives provide services to satisfy their farmer members (Huang and Gao 2012). Scholars have measured service qualities from two perspectives: member coverage of certain services (Chen and Tan 2013; Wang 2017) and the frequency of providing certain services (Deng et al. 2010; Huang and Gao 2012).The members’ coverage perspective of service qualities in Chinese pig cooperatives differs for input purchases and marketing services. For example, for certain cooperatives,100% of members purchase feed collectively, whereas other cooperatives have only several core members who procure feed collectively. The frequency of providing certain services also differs: some cooperatives provide more frequent veterinarian visits and training, while others provide fewer.

The existing literature suggests that the number and quality of cooperative services may influence farmers’ safe production behaviour (Van Hoi et al. 2009; Huang et al.2010), while very little empirical evidence of the same has been found (Wang and Wang 2012). The phenomena and research gap trigger our interest in knowing whether the number of services, service quality or both determine farmers’ safe production behaviour. Therefore, this research sheds light on the impact of cooperatives’ services on hog farmers’ safe production behaviour and contributes to the scant literature by providing empirical evidence from 540 cooperative hog farmers using cross-sectional data. Thisstudy attempts to answer the following question:

How do cooperatives’ service functions influence pig farmers’ safe production behaviour?

2. Theoretical overview and analytical framework

Cooperatives services in China have been widely discussed in recent years because services are the main operational content of farmers’ cooperatives, and in China, the number and quality of services provided by cooperatives are key criteria that the government uses to determine awards to cooperatives (MOA 2017). Current discussions focus on antecedents of why cooperatives provide good services(Yuan 2013; Zhong and Cheng 2013), and practices of how cooperatives provide good services (Tian 2016; Wan and Qi 2016), while very few studies have examined the possible outcomes that cooperatives will achieve through providing good services (Peng and Huang 2017).

2.1. Farmers’ safe production behaviour in the pig industry

Considering the current literature and interviews with experts in the animal sciences field (see Appendix A for the list of the experts interviewed), we use five specific perspectives to measure farmers’ safe production behaviour: feed use,breed use, vaccinations, drug use and production waste disposal (McGlone 2001; Nicholsen et al. 2007; Liu et al.2009; Plumed et al. 2009; Prapaspongsa et al. 2010;Missotten et al. 2015). For farmers’ feed use and breed use behaviours, we review whether the sourcing channels of the inputs meet safety and quality standards to measure their safety level1In China, farmers’ sourcing channels for feed and breed vary greatly. If the feed and breeds are purchased from branded companies,the risks associated with pig production are lower.; to clarify, if the sourcing channels have a potential safety risk, then the farmer’s production behaviour is not safe. For farmers’ behaviours in vaccination use, drug use and production waste disposal, we examine whether the farmer uses/adopts the inputs in a correct/safe way to measure their safety level2Whether farmers use vaccinations/drugs in safe ways is important to the safety of final products. If farmers overuse vaccinations/drugs, there will be drug residues left in live pigs’ body. Likewise, if farmers dispose of production wastes randomly to in nearby rivers,the production environment will be polluted, which will exert risks on pig production.. For instance, does the farmer use prescriptions strictly based on the instructions (i.e., the farmer adheres to the expiration date of the drugs)?

2.2. Cooperative services and farmers’ safe production behaviour

The extant literature provides some understanding of why and how different types of services offered by cooperatives change farmers’ safe production behaviour.Collective action theory offers some hints to understand the relationship between cooperative services and farmers’safe production behaviour. On one hand, collective action is advocated as a solution for small farmers to overcome resource constraints (Reardon et al. 2009) and provides farmers better access to inputs, better access to markets,reduction of transaction costs, increase bargaining power and acquisition of a collective reputation (Trienekens 2011;Naziri et al. 2014). Therefore, as cooperatives are “voluntary action taken by a group to achieve common interests(Marshall 1998)”, the main function of farmers’ cooperatives is to help farmers’ access services. On the other hand,Naziri et al. (2014) pointed out that collective action may facilitate the access of small farmers to demanding markets in terms of safety, primarily through increasing farmer capacity to undertake joint investments, providing farmers with information, technical assistance and proper inputs,making possible vertical integration or contract farming;and building favourable conditions for the establishment of public-private partnerships.

Input sourcing services not only help farmers achieve economies of scale but also help them reduce costs for finding and distinguishing among information, because smallholder farmers have a limited capacity to obtain inputs and may lack the knowledge to use these inputs (Little and Watts 1994; Dorward et al. 1998; Poulton et al. 2005). Wu et al. (2015) found that the main reason that farmers are not willing to use safe feed is because of its higher cost;input purchasing services offered by cooperatives would help farmers purchase good quality feed products and lower their costs through pooled purchasing services. Therefore,feed purchasing services may increase the likelihood of farmers’ use of safe feed products. Similarly, pooling the purchasing of breed piglets may encourage farmers to adopt better quality breeds.

Output marketing services are critical for farmers to access the market (Hellin et al. 2009). These services help farmers achieve more stable sales channels and possibly even better prices. When selling their products via cooperatives by contracts, farmers may reduce their opportunistic behaviour during production (Staatz 1987; Ji et al. 2012), and they may be more willing to abide by the best practice codes required by the cooperative because they expect to generate better sales income (Deng et al.2010; Chen and Tan 2013). Van Hoi et al. (2009) found that there is no successful enforcement mechanism within vegetable cooperatives to ensure correct pesticide use,mainly because the cooperatives do not significantly help their members’ market products via a safe vegetable channel. Therefore, marketing services have an effect on farmers’ safe production behaviour by reducing opportunistic behaviour and by causing farmers to expect to achieve better sales income if they adopt safer practices. Technological services, such as training and veterinarian services, may influence farmers’ safe production behaviour by enhancing their perceptions and knowledge of vaccination and drug use(Wang 2009). Thus, when a cooperative can provide better services to satisfy its member farmers, the more likely is that member farmers will abide by the cooperative’s production requirements. As stated in the introduction, the service quality of the cooperatives refers to how well cooperatives provide services to satisfy their farmer members (Huang and Gao 2012). We propose that the better the service quality cooperatives can offer is, the more likely farmers will be to produce pigs safely (H1).

H1: When a cooperative provides better quality services,each farmer engages in safer production behaviour.

The number of services provided by cooperatives refers to how many different types of services a cooperative provides (Tang 2007). Huang et al. (2010) used the number of services to indicate whether a cooperative is strong in providing services, and cooperatives that provide more types of services are considered strong in helping farmers improve their income, production skills and bargaining power. Asstated in the previous two paragraphs, input purchasing services, marketing services and technological services are all related to improving farmers’ safe production, and it is therefore proposed that the more services are provided by a cooperative, the higher the possibility that member farmers are able to obtain different types of services, thus improving their safe production behaviour (H2).

H2: When a cooperative provides more services, its member farmers’ safe production behaviour improves.

2.3. Farmers’ production scale, demographic factors and their safe production behaviour

Small scaled pig farming has long dominated China’s pig production (Ji et al. 2012), and small scale farmers are seen less likely to adopt safe production practice codes than large scale farmers (Zhou et al. 2015). Large-scale farmers are more able to improve their production infrastructure because they have more capital resources (Hall et al. 2004). In China, large-scale pig producers are more likely to purchase branded inputs because of the economies of scale they achieve will reduce their production cost. Current studies have also revealed that production scale is an important factor influencing pig producers’ safe production behaviour(Wang 2009; Wang and Wang 2012). Thus, it is proposed that the larger a farmers’ production scale is, the safer its production behaviour (H3).

H3: Production scale has a positive relationship with the safety level of farmers’ production behaviour.

Demographic features of farmers are widely discussed in farmers’ behaviour studies (Hu and Chen 2012; Ji et al.2017). The demographic characteristics, such as gender,age, education, production experience, and whether the farmer is village cadre, are all seen as factors that influence farmer’s safe production behaviours in China (Liu et al.2009; Hua and Chang 2011). To be more specific, a more educated farmer with more production and work experience will produce pigs in safer ways (Wang 2009; Zhong et al.2016). Similarly, a farmer who specializes in pig production and who has a greater labour force at home will also produce pigs in safer ways (Zhang and Fu 2016). Therefore, we propose that farmers’ demographic characteristics also influence farmer’s safe production behaviour (H4).

H4: Farmers’ demographic characteristics (age,education, production experience, working out experience,specialization in pig production, family labour force)influence farmer’s safe production behaviour.

3. Methodology and data collection

3.1. Methodology

Based on the hypotheses proposed, it requires multivariate regressions to identify the multiple factors that can jointly determine the famers’ safe production decisions. As discussed in the previous section, all factors that potentially affect the famers’ safe production behaviour should be included in the regression. Discrete choice model, such as probit and logit is a standard model utilized to analyse determination related to the decisions of farmers to safe production behaviours.

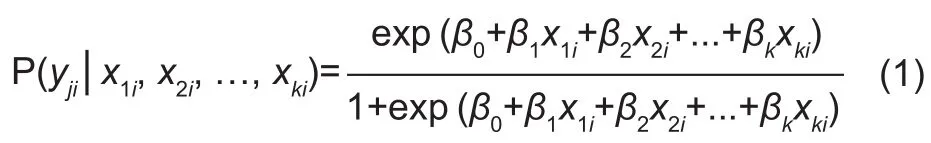

The logit model and maximum likelihood estimation(MLE) are used to estimate the probability that a farmer engages in safer production behaviour, as a function of all the factors that might influence the famers’ safe production behaviours, we will have

In eq. (1), yjiis a dependent binary variable (=1, farmer engages in safe production behaviour; =0, otherwise), P is the probability for famers to take safer production behaviours.x1i, x2i, ..., xkiare the independent variables to be estimated.Specifically, the independent variables include the quality of services provided by cooperatives (Hypothesis 1),the numbers of services (Hypothesis 2), farmers scale(Hypothesis 3) and farmers’ demographic characteristic(Hypothesis 4).

3.2. Data collection and descriptive statistics

Data collectionTo conduct the research, we first usedstratified sampling to choose the provinces for the survey.Traditionally, 90% of pig production in China occurs in four major regions: the coastal region, the inner-middle region, the south-western region and the newly emerging north-western region (MOA 2009). For our sample base,we randomly chose one province from each of the regions mentioned above, and they are Zhejiang, Shandong, Anhui and Sichuan provinces, respectively. Then we selected the main pig production prefectures from the four provinces,where 27 pig cooperatives were generated for our study3Sample cooperatives operate in Hefei (4), Suzhou (2), Quzhou (3), Jinhua (4), Weifang (4), Jining (3), Chengdu (4), and Suining (3)..As the number of services and service quality are the focus of our analysis, the selection of the cooperatives was conducted based on the number of services they offer using the following steps:

1) We contacted the local livestock bureaus for these prefectures and obtained lists of registered pig cooperatives.

2) We called the responsible persons for each cooperative,asked how many services they provide, and recorded the number.

3) Double stratified sampling was adopted to determine how many cooperatives we should choose for each service number level and for each province. Although the ratio of cooperatives for each service number level is not 1:1:14Based on the data from the local livestock bureaus in the survey areas, we found that in fact, the proportion of these cooperatives is 5 (service number level 1):3 (service number level 2):1 (service number level 3), and the corresponding weights are adopted in the regressions.,we ultimately selected 9 cooperatives for each level so that the impact of level 3 could be more clearly shown. Then,the cooperatives were randomly selected from each specific service number level and each province (Table 1).

Ultimately, and from each of the 27 cooperative, 20 farmers were randomly chosen to answer a questionnaire regarding their production behaviour, and 540 cooperative farmer questionnaires were effectively collected. It should be noted that to measure each farmers’ safe production behaviour, not only were the questions appearing in Table 2 asked but also physical checks and supportive questions were combined to validate the trustworthiness of the farmers’answers to ensure the validity of the data collected.

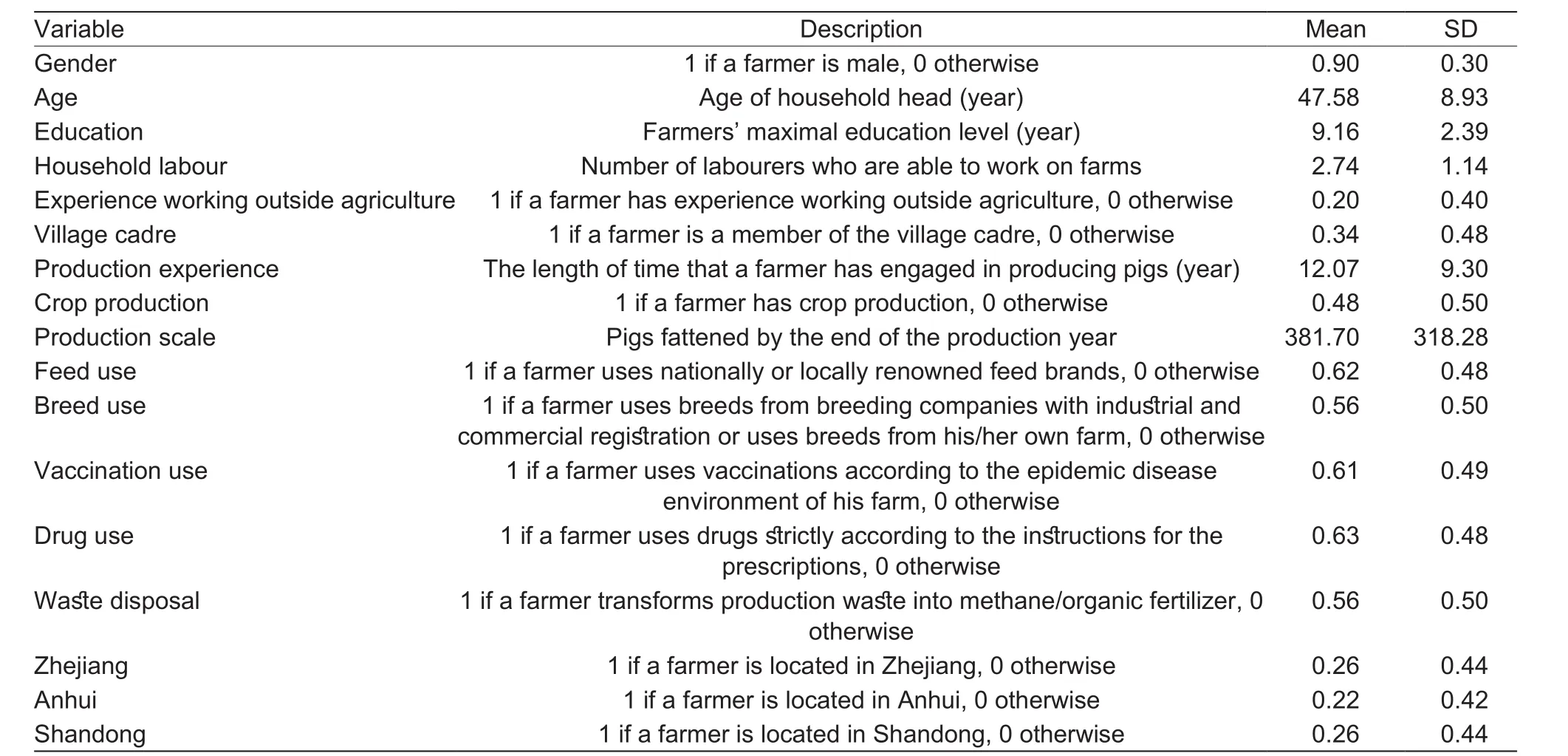

Descriptive analysisBefore running the regression, some descriptive statistics are reported. Table 2 indicates that 90% of the farmers are male, and cooperative farmers are approximately 47 years old and received approximately 9 years of education. Most farmers do not have experience working outside agriculture, and they have been engaged in pig production for a long time; 50–60% of the farmers could safely produce pigs.

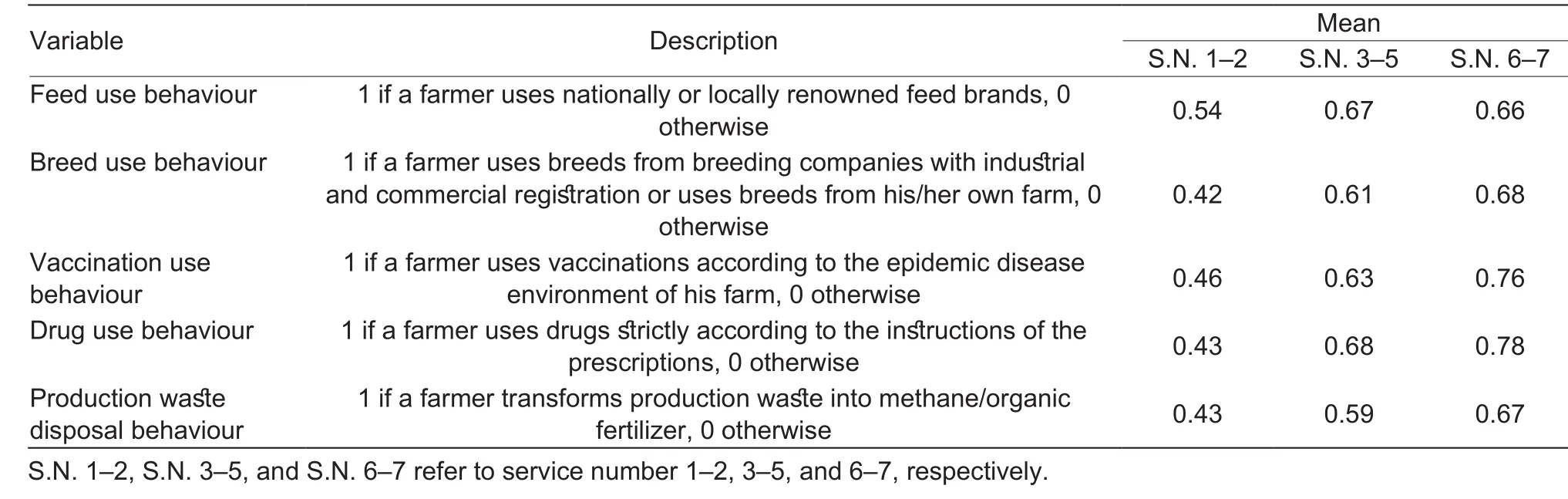

From the descriptive statistics provided in Table 3, we note that farmers’ production behaviour becomes safer as the number of service functions provided by the cooperatives increases. Farmers’ safe production behaviour significantly improves when the service number increased from the 1–2 level to the 6–7 level. Therefore, it appears from the descriptive analysis that service number has a positive influence on farmers’ safe production behaviour.

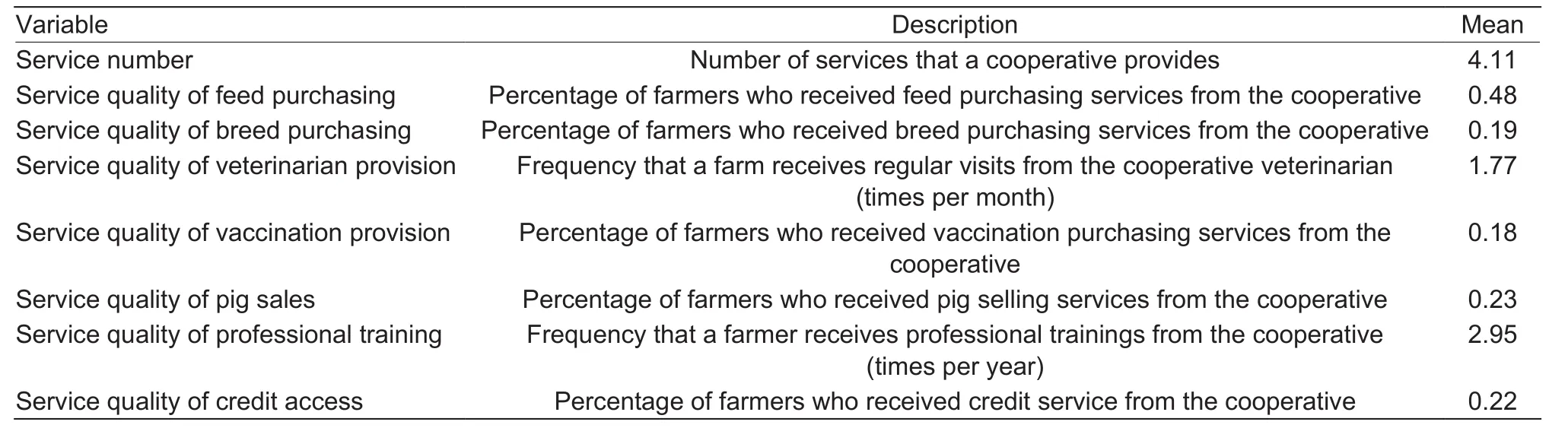

Table 4 illustrates how this research measures service number and service quality. We used the percentages of farmers who received services to measure the quality of the services related to feed purchasing, breed purchasing,vaccination provision, pig sales and credit access, and we used the frequency of veterinarian visits to measure veterinarian services and the frequency of professional trainings. The two functions that are most frequently offeredby cooperatives are feed purchasing and professional training; this finding aligns with the fact that cooperatives generally start by providing non-operational services (e.g.,training) and then move to engaging in operational activities(e.g., feed purchases, pig sales, etc.). The three functions least often offered by cooperatives are credit capital,vaccination purchases and breed purchases.

Table 1 Geographic distribution of sample cooperatives based on their service number

Table 2 Variable definitions

Table 3 Member farmers’ safe production behavioural differences among three number levels

Table 4 Descriptive data for service quality of sample cooperatives

As mentioned in introduction part, cooperatives in China are categorized into two types in terms of ownership, which are farmers-owned cooperatives and IOF-led cooperatives.In pig industry in China, farmers-owned cooperatives vary in terms of cooperative size, ownership and control. It is found that in the sample farmers-owned cooperatives of this research, there are farmers-owned cooperatives formed by large-scale pig producers, cooperatives formed by small-scaled producers, as well cooperatives formed by a mixture of both large-scale and small scaled farmers, and safe production behaviours of farmers in these different cooperatives vary a lot. Therefore, we describe the types of cooperatives of the whole sample from ownership perspective, and from scale perspective for farmers-owned cooperatives.

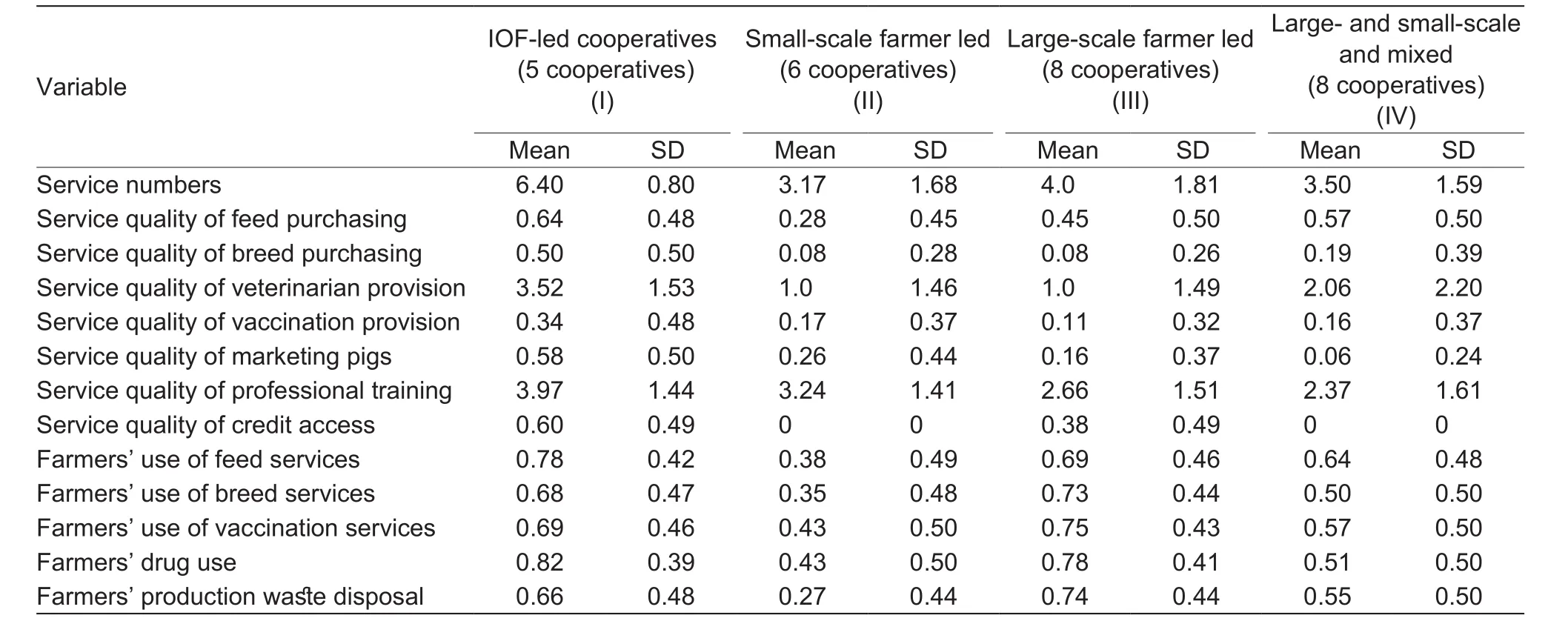

From Table 5, we can see that, among the 27 sample cooperatives, 5 are IOF-led cooperatives (cohort I), 6 are small-scale farmer-initiated cooperatives (cohort II), 8 are large-scale farmer-initiated cooperatives (cohort III), and 8 cooperatives are either large-scale farmer cooperatives or small farmer mixed cooperatives (cohort IV). The five IOF-led cooperatives are led by five different companies in pig industry, and they are 2 pig production companies(WENS Food Group Co., Ltd. (Xinan Branch) and WENS Food Group Co., Ltd. (Anhui Branch)); 1 pork processing company (Zhejiang Huatong Meat Co., Ltd.); 2 vertically integrated companies (Sichuan Gaojin Food Co., Ltd.and Delisi (Delicious) Food Co., Ltd. (Shandong)). The production scales of small-scale farmer-initiated cooperative range from 10 to 100 heads of pigs, production scales of large-scaled farmer-initiated cooperative range from 700 to 1 300 heads of pigs, and production scales of large-scale and small-scale mixed farmers cooperative range from 120 to 670 heads of pigs.

We describe the service numbers, service quality and farmers’ behaviours according to the four groups in Table 5.IOF-led cooperatives are found to provide more services(6.4) than the other types of cooperatives (3.17, 4.0 and 3.5, for cohorts II, III, and IV, respectively). In addition,IOF-led cooperatives provide all types of services better(from 0.34 to 3.97). Small-scale farmer-led cooperatives provide the fewest services (3.17), and for most services,the quality is worse (from 0 to 3.24) than the other types of cooperatives. In IOF-led cooperatives, farmer behaviour is better than in small farmer-led cooperatives. Therefore, a positive relationship between service quality and farmers’behaviour could be proposed. Regarding cohorts (III) and(IV), the quality of three types of services in cohort (III) are better, and the quality of four types of services in cohort (IV)are better, which means that the service quality of these two groups do not differ as much as the quality between cohorts(I) and (II). Farmers’ behaviour in cohort (III) is better than that of cohort (IV). This might indicate a positive relationship between the production scale and farmers’ safe production behaviour. Regarding cohorts (II) and (IV), the numbers of services provided are similar. The service quality in feed purchasing, breed purchasing and veterinarian provision of cohort (IV) are better, while the service quality of marketing pigs and professional training of cohort (II) are better. These findings are in line with the fact that the main reason why large-scale farmers in China unite to form cooperatives is to achieve economies of scale from pooling purchasing, while they have fewer incentives to sell pigs together, believing that each has their own sales channels. Farmers’ safe production behaviours of cohort IV are generally better thanthat of cohort II, but it is difficult to conclude that differences in behaviour come from the difference in service quality versus production scale, or both.

Table 5 Service quality and farmers’ safe production behaviour for four types of cooperatives1)

Table 6 Regression results of eq. (1) (farmer’s behaviour and its determinants)

4. Results and discussion

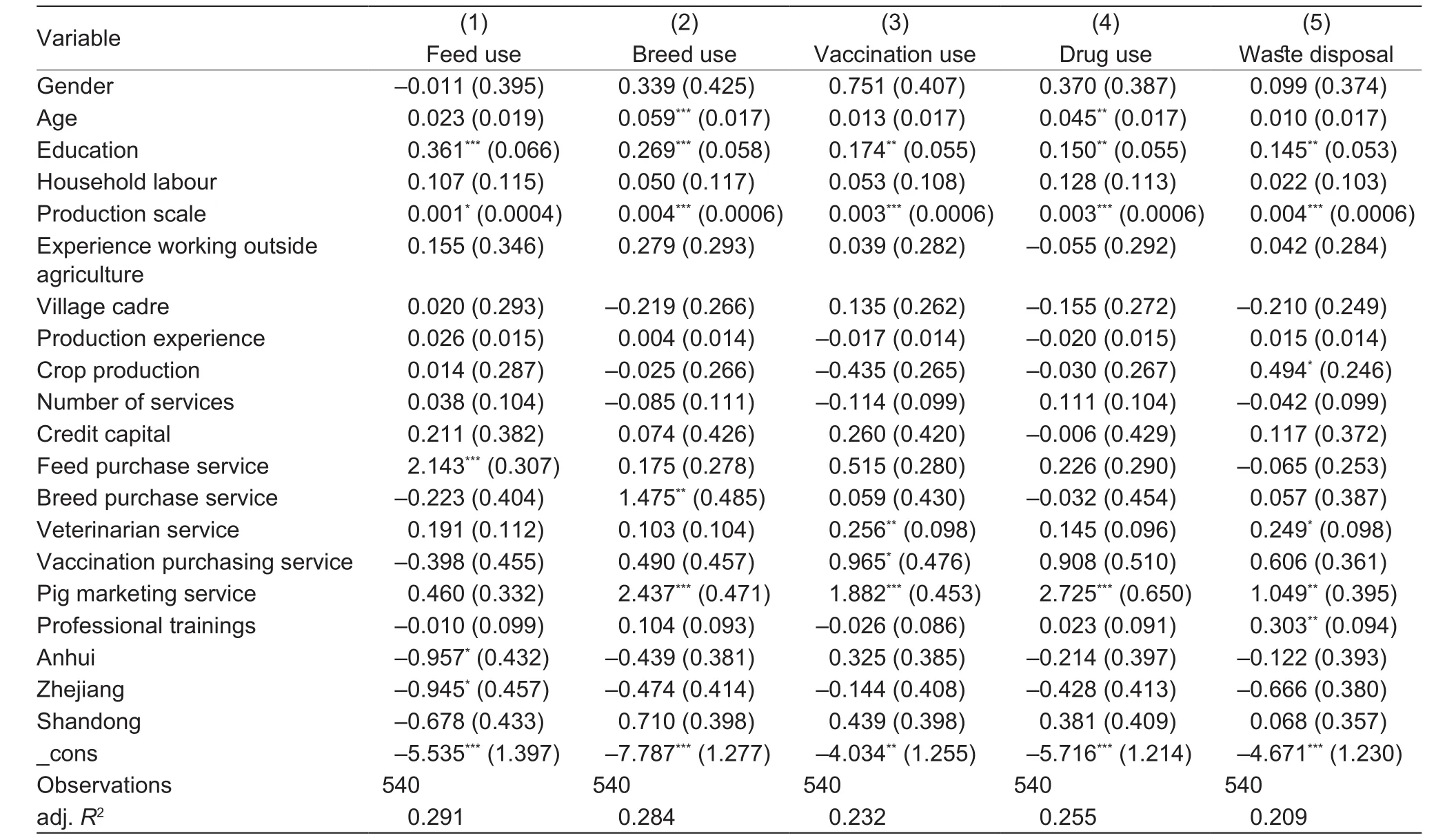

Some findings can be generated from the regression results(Table 6). Education plays an important role in farmers’ use of services related to feed purchases, breed purchases,vaccination purchases and drug use behaviour, which means that farmers with higher education levels tend to use safer methods to produce pigs. The production scale evidently influences farmers’ safe production behaviour in positive ways; farmers operating at a larger scale tend to produce pigs in safer ways. Pig production experience only affects farmers’ feed use behaviour; farmers who do not engage in crop production appear to engage in safer behaviour regarding waste disposal.

Regarding the factors related to service functions,although the descriptive data show that farmers’ safe production behaviour improves with better service quality,the regression data do not support this result, which means that a cooperative that provides more service functions is not necessarily more capable of ensuring farmers’ safe production behaviour. With regard to service quality,however, services related to feed purchases have an effect on farmers’ feed use behaviour and vaccination behaviour,and they have a more significant and greater influence on farmers’ feed use behaviour than on farmers’ vaccination use behaviour. Services related to breed purchases significantly contribute to improving farmers’ safe production behaviour as related to the use of pig breeds. Veterinarian services are important for improving farmers’ behaviour related to feed use, vaccination use and waste disposal. These services have the most significant and greatest influence on farmers’vaccination use behaviour, followed by waste disposal, then feed use. Services related to vaccination purchases have an effect on the vaccination use, drug use and waste disposal behaviour of farmers. Unsurprisingly, the influence of these services on vaccination use is the most significant and greatest. Pig marketing services have a significant effect on farmers’ production behaviour of breed use, vaccination use, drug use and waste disposal; the influence of these services on these behaviours are all significant at the 1%level, and the greatest influence is on drug use, followed by breed use, vaccination use, and waste disposal. This result means that when farmers sell their pigs through the cooperative to certain downstream stakeholders, they tend to use drugs in safer ways. Professional training only has an influence on farmers’ production behaviour related to waste disposal, while credit services do not have an effect on any of the farmers’ safe production behaviour.

The regression results indicate that farmers’ safe production behaviour will not be improved if the cooperative provides more services, but it may be improved with better services. The results of this study also imply that a cooperative that provides more services does not necessarily provide good services. By helping more farmers unify feed purchasing, breed purchasing, vaccination purchasing and pig selling and by providing more veterinarian visits, farmers’safe production behaviour will improve. In our study, pig selling services play a significant role in ensuring farmers’safe production behaviour. The results also indicate that the effect of the training offered by the cooperatives in China is not good, which implies that this training only influences farmers’ waste disposal behaviour.

5. Conclusion and implications

Based on the results, we can answer the research question that was proposed at the beginning of the study affirmatively:the services offered by cooperatives do influence farmers’safe production behaviour. The number of services is not the key determinant, but the quality of the services determines farmers’ safe production behaviour. Farmers’ education level and production scale are two other factors that may influence farmers’ safe production behaviours. Hence,several implications are drawn. First, pig farmers should produce pigs using safer methods; it is important to enhance farmers’ education levels to help them better understand and absorb the best practices that cooperatives require of them. Second, scaled farming should be encouraged because small farmers’ behaviour is less safe and harder to control. This result aligns with the current policy that is being instituted in China’s pig industry. Third, to make farmers use branded feed products, cooperatives shouldstrive to unify feed purchasing services to as many member farmers as possible. This would improve farmers’ feed use behaviour and help member farmers generate economies of scale. Fourth, cooperatives must help farmers collectively purchase breeds or encourage them to use breeds reproduced by their own farms instead of purchasing from unknown farms or companies. This will ensure that the breeds used are safe and resistant to epidemic diseases.Fifth, veterinarian services should draw cooperatives’attention because veterinarians are professionals who can provide suggestions and treatments; more veterinarian visits should be offered, regardless of whether they are offered solely by the cooperatives or jointly by the cooperatives and their collaborative companies. Farmers’ safe production behaviour would be substantially improved by learning how to use vaccinations, how to address waste and which feeds to purchase. Services related to vaccination purchases should also be enhanced; cooperatives should help farmers understand the importance of using vaccinations and drugs according to the environment of the farm and the importance of transforming pig waste into methane and organic fertilizer.Finally, the importance of services related to collective pig selling is addressed. Cooperatives could collaborate directly with downstream stakeholders or connect with brokers in the countryside to help farmers sell pigs. This appears to be the most effective way to improve farmers’ safe production behaviour. Furthermore, providing pig selling services will contribute to stabilizing farmers’ income that is generated from raising pigs.

To conclude, cooperatives in China contribute to improving farmers’ safe production behaviour through providing different types of services, and the better the quality of the services they provide is, the safer the farmer’s production behaviour will be. The Chinese government should take measures to help cooperatives provide better services to ensure farmers engage in safe production behaviour, which would enhance food safety in the pig industry.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71403243 and 71403077).

Appendixassociated with this paper can be available on http://www.ChinaAgriSci.com/V2/En/appendix.htm

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2018年10期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2018年10期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- The trade margins of Chinese agricultural exports to ASEAN and their determinants

- Effects of lairage after transport on post mortem muscle glycolysis,protein phosphorylation and lamb meat quality

- Beneficial role of melatonin in protecting mammalian gametes and embryos from oxidative damage

- Molecular identification and enzymatic properties of laccase2 from the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae)

- ldentifying glyphosate-tolerant maize by soaking seeds in glyphosate solution

- Genetic diversity and population structure of Commelina communis in China based on simple sequence repeat markers