“那么,为什么是多西?”

[荷] 亚历山大 · 佐尼斯 [荷]利亚纳 · 勒费夫尔 文 Written by Alexander Tzonis & Liane Lefaivre黄卿云 译 Translated by Huang Qingyun

黄鸟在自己的树上歌唱,使我的心喜舞。

我们两人住在一个村子里,这是我们的一份快乐。

她心爱的一对小羊,到我园树的荫下吃草。

它们若走进我的麦地,我就把它们抱在臂里。

我们的村子名叫康遮那,人们管我们的小河叫安遮那。

我的名字村人都知道,她的名字是软遮那。

罗宾德拉纳特 · 泰戈尔,《园丁集》,1913年

——冰心 译

3月7日,一个令人欣喜的消息传来,巴克里希纳 · 多西获得了今年的普利兹克建筑奖。这个消息提醒着我们,在当下,即使积重难返的建筑伪繁荣正侵蚀着环境,并对社区、文化、社会多样性及生态多样性造成不可逆转的破坏,却仍然有一些人文主义建筑,存在于我们周围。

作为建筑界的“诺贝尔奖”得奖人,多西呼吁建筑师放下对“个人”设计身份的痴迷,重新思考自己的职业能够为贫困的社区建设做些什么。他的闪光之处在于对“居者”心怀“同情”与“尊重”,并寻求与他们的“协作”。

虽然在演讲中,多西的“居者”指的是印度地区的穷人,但是他传递的信息却对全人类普遍适用。他的观点也让人回想起另一位重要的印度学者——经济学家阿玛蒂亚森(Amartya Sen)在接受瑞典皇家科学院(Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences)颁发的诺贝尔和平奖时的讲话中提到,“(需要)重塑重要经济问题讨论的道德维度”。

阿玛蒂亚森将世界上最贫困的人群也纳入视野,以“开放新领域”的方式重新定义了“经济学”。多西则将目光聚焦在那群“没有土地、没有住所、没有工作的一无所有的人”,从而拓宽了“住房”的界限。他重新次定义了建筑师的角色,如他所言“(建筑师的工作包括)感知影响你的因素,以及内心抑制不住的冲动……我们周围的每一物体和自然本身——光线、天空、水和风暴——所有一切……融合而成的交响”。最终,他坚信“建筑并不仅仅是房子……建筑师还需要起到社会活动家的作用”。

除了成为一名创意的实践者外,多西的身份还包括教师和机构创始人。他是艾哈迈达巴德建筑学院的创始人(1962-1972年),学院规划系的初创人(1972-1979年),环境规划与技术中心的创立人和第一任主任。

1947年,多西在孟买开始了自己的建筑学习,同年,印度独立建国。1954年,他环顾四周,企望在全新的社会环境中寻找到自己的定位。他说:“我想我应该立下一个我将终生守护的誓言:为社会最底层的人提供适宜的居所。”此外,尽管他满怀社会责任感,尽力迎合一个全新印度国家的需求,他依然感到,有必要放眼域外,去关注印度周围国家已有的经验,并将其重新利用。

20世纪50年代初,多西去到欧洲,并在一次会议期间遇到了勒 · 柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)。从1951年起,他就开始在勒 · 柯布西耶手下工作。工作是义务的,没有酬劳。但这十二年的共事中,勒 · 柯布西耶所给予的,却远非金钱可以衡量:他与多西在专业和私人层面都建立了深厚的友谊,并毫无保留地将自己仅有的情感与建筑信仰与多西一一分享。

1958年,在奖学金的支持下,多西游历美国。他去拜访了路易斯 · 康的作品——理查兹医学研究大楼。多西崇拜这座建筑对砖材炉火纯青的使用,这种方法与勒 · 柯布西耶使用的施工技术完全不同,可以作为砖材建造的替代选项。他在路易斯 · 康的办公室第一次见到了康,这是一次非常愉快温馨的相遇。交谈后,路易斯 · 康请多西共赴晚餐。而多西则惊讶地发现,原来这么伟大的建筑师也需要向自己的秘书借钱吃饭。

图1

图2

图3

图4

图5

图6

图7

图8

图9

图10

图11

图12

图13

图14

图1~图7:阿冉亚低造价住宅,印多尔,印度,1989年

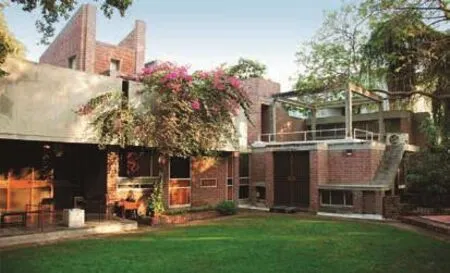

图8~图14:环境规划与技术中心,(现CEPT大学),(多期工程)艾哈迈达巴德,印度,1966-2012年

The yellow bird sings in the tree and makes my heart dance with gladness.

We both live in the same village, and that is our one piece of joy.

Her pair of pet lambs come to graze in the shade of our garden trees.

If they stray into our barley field, I take them up in my arms.

The name of our village is Khanjanā,and Anjanā they call our river.

My name is known to all the village, and her name is Ranjanā.

Rabindranath Tagore, The Gardener 1913

That Balkrishna Doshi has won the Pritzker architectural prize on 7 March, is a most welcome recognition that there is still a humanist architecture today in the midst of a mostly oppressive architectural affluence that has brought environmental poverty and an irreversible destruction of community and cultural, social and ecological diversity.

Doshi, recipient of the so called ’Nobel prize’, of architecture, called on his profession to rethink the way it approaches building for the most impoverished communities and move away from their obsession on ‘the designer as individual’. His values were ‘collaboration’,‘compassion’, and ‘dignity’ ‘for those they house’.

In his speech Doshi was referring to India’s poor but the message was a universal addressing of humanity. His statement recalled the statement to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences that awarded the Nobel prize to another most important Indian, the economist Amartya Sen, for "restor(ing) an ethical dimension to the discussion of vital economic problems."

As Sen redefined ‘economics’ by‘open(ing) up new fields of study,’ including the poorest people of the world, Doshi‘opened’ the definition of ‘housing’studying ‘these people’ who ‘have nothing- no land, no place, no employment’. He redefined the role of the architect, as he outs it, ‘to include what affects you and what triggers in you a sense of being alive…every object around us, and nature itself—lights, sky, water and storm—everything…in a symphony.’ Ultimately, he believes that the ‘architecture profession is not only the building itself… the role of the architect is also to be a social activist.’

Apart from being a creative practitioner,Doshi is a teacher and an institutional builder.He was the Founder Director of School of Architecture, Ahmedabad (1962-1972),first Founder Director of School of Planning(1972-1979), first Founder Dean of Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology(1972-1981).

He began studying architecture at Mumbai in 1947, the year India gained independence. In 1954, looking around to identify his place in this emerging novel world,he declared ‘It seems I should take an oath and remember it for my lifetime: to provide the lowest class with the proper dwelling’.On the other hand, although committed to social responsibility, serving the needs of the new India he felt the country had to master and re-use the experience of the world that surrounded it, including these countries that for years had exploited it.

By the beginning of the 1950s, Doshi went to Europe and during a conference,he met Le Corbusier. Le Corbusier offered him a job starting 1951, but no payment.However, for over twelve years, what he did offer him was a most important reward,his camaraderie professional and personal,sharing with him his wisdom, his sentiments and his belief in social architecture.

Later, in 1958, supported by a scholarship,Doshi travelled to US and visited Louis Kahn' s Richards Medical Building. In it, he admired the use of brick, so different from Le Corbusier' s use of materials, suggesting alternative construction techniques. He met Kahn in his office for the first time. It was a very warm encounter. Kahn invited him to dinner but Doshi noted to his surprise that the great architect had to borrow money from his secretary.

In 1960 and 1961, Doshi met Kahn again in Philadelphia, and their friendship deepened. In 1962 Doshi invited Kahn to design the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad and Doshi became his assistant although they worked closely together as collaborators until Kahn' s death in 1974.

There is a false impression that what attracted Kahn and Doshi to each other outside of technical questions was the world of mysticism. They were, indeed, familiar with it within their own culture. In fact, it appears they talked about the depression, poverty, and probably about Kahn' s early commitment to social housing during the Roosevelt years.

图15

图16

图17

在1960和1961年,多西又在美国费城遇到了路易斯 · 康,这几次见面加深了他们的友谊。1962年,多西邀请路易斯 ·康设计印度阿默达巴德管理学院,自己则出任他的助手。从那之后,他们一直密切合作,直到1974年路易斯 · 康去世。

人们总有一个错误的印象,那就是觉得,让路易斯 · 康和多西互相吸引的,除了技术问题之外,是他们对神秘主义语境的兴趣。他们确实分别在各自的文化语境中对此熟知。但事实上,他们讨论过社会萧条、贫困,还有路易斯 · 康早年在罗斯福时代时许下的对社会保障住房的豪言壮语。当然,他们也讨论桑鲁卓和《一千零一夜》的故事。这部文学作品是多西介绍给路易斯 · 康的,而后者进而对其陷入着迷。在笔者佐尼斯的自传笔记里,写道,彼时,自己在费城遇到了路易斯 · 康,他俩的交流除了围绕柏拉图之外,主要都是关于这部伟大的文学作品的。

是什么,让作为建筑师的多西和路易斯 · 康对这些神话故事里塑造的世界充满好奇?是当人们不为利益所驱动时,对生活朴素的热爱、幸福的感受和交流的快感。这样的世界,正是印度诗人兼哲学家,同时也是诺贝尔奖得主罗宾德拉纳特 · 泰戈尔所推崇和向往的。多西成长的年代,正是泰戈尔受到极度尊重的年代。他“国家普遍主义”的观点,深厚的人文主义色彩与他那泛情的生活方式,都在文初引用的诗句中尽情展现。1967年,多西设计了位于艾哈迈达巴德的泰戈尔纪念馆。多西对路易斯 · 康产生的影响也是毋庸置疑的,比如,1959年,在他们第一次相遇一年后,路易斯 · 康就申请加入了费城泰戈尔协会。

在20世纪80年代设计并建造的阿冉亚低成本住房,是多西最具代表性的重要作品之一(图1,图2)。这个项目的服务群体是近80000名“一无所有”——“无土地、无职业、无住房”——的底层人民,和约6500户中等收入住户。按照多西的原则,他放弃了“集合”住宅的方法。阿冉

图18

图19

图20

图21

图22

图23

图24

图25

图15~图23:桑珈建筑师工作室,艾哈迈达巴德,印度,1980年

图26

图27

图28

图24,图25:Vidhyadhar Nagar总体规划与城市设计,斋浦尔,印度,1984年But they also talked about Scheherazade and the Tales of a Thousand and one Nights,a work of literature that Doshi introduced Kahn to and that Kahn subsequently became fascinated with. On an autobiographical note,about the same time Tzonis met Kahn for the first time in Philadelphia and a major part of their discussion, apart from Plato, was indeed about this great literary work.

What attracted Doshi and Kahn as architects to the world of these stories was the archaic, pre-market attachment to the love of life, the feeling of happiness and dialogue,when people celebrate their life beyond profit.This was a world espoused by the great Indian poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore, also a Nobel Laureate. Of course, Doshi was brought up in a society in which Tagore was held in the greatest esteem, because of his ‘nationaluniversalism’, his deep humanism and his panerotic approach to existence—all apparent in the poem quoted above. In 1967, Doshi got to build the Tagore Memorial Hall in Ahmedabad.Another mark of Doshi' s influence on Kahn was that in 1959 Kahn joined the Tagore Society of Philadelphia, in the year following their first encounter.

One of the most significant and most representative works by Doshi was the Aranya Low-Cost Housing (designed and built during the 1980s) project for a staggering 80,000 people, mostly for ‘people have nothing -no land, no place, no employment’ but also for about 6,500 middle-income residences.Following his principles Doshi did not design an aggregation of ‘houses’. The word Aranya refers to a world embedded, not cut off from nature. It is an ecology enabling privacy through inward-looking clusters together with dialogue,sharing, cooperation through common open spaces, paths, and parks.

Despite the difference in scale and program we find the same design principles,the same attitude towards nature and community in Doshi' s earlier institutional projects such the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT University)(Ahmedabad, 1966-2012), in his own studio in Ahmedabad, (1980) or in the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore (1992),in his own Kamala house (Kamala is his wife' s name) and in Amdavad Ni Gufa (Ahmedabad,1994), ‘as in tales’‘cave like’ ferro-cement art gallery, featuring art works of Maqbool Fida Husain .

The Chinese public is familiar with Doshi's work. The most important presentation of the past 60 years of his work took place at the Power Station of Art Museum in Shanghai in 2017. The title was 'Celebrating Habitat: ‘The Real, the Virtual and the Imaginary'. What could Doshi say to the Chinese? What could he say to the rest of the world outside India? Like every part of the world, China is unique, what was then the relevance of Doshi to China?

Doshi did not argue in favor of using architecture as the symbolic expression of this uniqueness. Rather, he thought and thinks that there may be other values apart from symbolism, higher standing up in terms of architectural priorities. This is illustrated in an incident described in a recent book (You say to brick: the life of Louis Kahn, 2017),by Wendy Lesser. It relates how Safdie, as a student working for Kahn in the late fifties,asked him why he does not take architecture‘out of the Stone Age.’ In other words, why he does not apply highly industrialized construction methods instead of sticking with bricks. Kahn's answer had little to do with the problem of identity or so called ‘nationalist consciousness.’It was pragmatic: ‘You have to work with what people have’ he said. In the last analysis he was arguing for a kind of regional realism rather than for fake regionalism.

A similar argument can be repeated about Doshi' s ‘low-cost’ building solutions.In the 1960s, Doshi reused material from constructions sites. Aldo van Eyck in the early 1950s and Wang Shu, later, did the same. He also employed limited space configurations respecting tight sites. These decisions grew out of the constraints of the region of India.But they are not an expression of mentality or of India' s poverty. They are an expression of a spirit of rational realism whereby, as Doshi says himself, ‘a truly sustainable city is a city where the least human energy and time is spent in getting things done, not for profit but for the ‘people (to) have time for reflection and…… once again act like human beings, not the robots they have been forced to become.’ This view is eminently true for India and it is also true for the world,including China.

图29: 设计灵感源自1987年普利兹克建筑奖得主丹下健三先生所设计的仓敷市政大厅

图30

图31

图32

图33

图34

图35

图36

图37

图38

图39

图40

图26~图28:印度管理学院班加罗尔分校,(多期工程),班加罗尔,印度,1977-1992年

图29~图34:印度学研究所,艾哈迈达巴德,印度,1962年

图35~图37:Premabhai 大厅,艾哈迈达巴德,印度,1976年

图38~图40:卡玛拉家宅,艾哈迈达巴德,印度,1963年亚(Aranya)这个词在印度语中,代表着一个与自然融为一体的世界。多西也试图创造一种生态,在其间,既有内向的集合保证住户隐私,也有开放的公共空间、小径和公园为居者提供对话、共享和协作的场所。

尽管在项目规模和类型上各不相同,但我们仍然可以在多西工作室的许多设计作品中——例如位于艾哈迈达巴德的建筑学院环境规划与技术中心大学CEPT(1966-2012)、他的桑珈工作室在班加罗尔的印度管理学院(1992);他以夫人名字命名的自宅——卡玛拉家宅;在艾哈迈达巴德的洞穴画廊(1994),一座如“故事般”似“洞穴样”的,展出马克布勒 · 菲达 · 侯赛因(Maqbool Fida Husain)作品的水泥艺术画廊——找到相同的设计原则和对多西自然与社区不变的态度。

中国公众对多西的作品应该并不陌生,2017年,由发电厂改建的上海当代艺术博物馆,推出了“栖居的庆典:真实· 虚拟 · 想象——巴克里希纳 · 多西建筑回顾展”。展览展出了过去60年多西的众多代表性作品。多西想对中国观众们说些什么?又或者说,多西能对印度以外的世界说些什么?中国,同世界的每一个角落一样,独一无二。那么,多西和中国之间又有怎样的关联?

多西并不是那种将建筑作为某种独特性的象征物来表达的建筑师。相反,他在思索,并始终相信,在象征性之外,建筑可以有更高的追求。在最近出版的图书《与砖对话:路易斯 · 康的一生》中,作者温蒂 · 莱塞描述了萨弗迪(Safdie)与五十多岁的路易斯 · 康之间的对话。彼时,正在路易斯 · 康手下工作的萨弗迪问自己的老师,为何不干脆造“石器时代”建筑算了?换句话说,他是想问,为什么不采用高度工业化的建筑方法,而偏偏选择用砖?路易斯 · 康的回答出乎意料地与“认同感”或“民族意识”不太相关,而是朴素务实的。他说:“你必须用人们手上拥有的材料设计。”在路易斯 · 康职业生涯的后期,他的立场更多的是一种尊重地域的现实主义,而不是“伪地域主义”。

在多西的“低成本”建筑方案中,我们可以看到类似的立场。20世纪60年代,多西会从建筑工地中回收建材。比他早期的阿尔多 · 凡 · 艾克和后来的王澍亦是如此。他用紧凑的空间配置回应局促的场地。这些方法都与印度当地的制约条件相对应,但并不着意表现印度人的心态或是地区的贫困,而是希望展现一种理性的现实主义精神。正如多西所言,“一座真正可持续发展的城市,应该是人们用最少的力气和最短的时间去搞定事情。这么做不是为了获取利益,而是为了让人们有时间进行‘人类的’思考与行动,而不是成为效率奴隶下的机器人。”这个观点在印度行之有效,而且放之四海而皆准,包括中国。

图41

图42

图43

图44

图45

图46

图47

图片来源

图4、图6 John Paniker摄

图11、图21、图23、图41、图43 李之吉摄

图40 由A+U提供

剩余图片照片由VSF提供

感谢凯悦基金会和吉林建筑大学李之吉教授对本文图片收集工作的支持。

图41~图45:艾哈迈达巴德洞穴画廊,艾哈迈达巴德,印度,1994年

图46,图47:人寿保险公司混合收入住房,艾哈迈达巴德,印度,1973年