伟大的城市公园:环境、持续和连接的重要性

著:(英)阿兰·塔特 译:曹新 校:吴龙峰

导言

我对于城市公园的研究兴趣始于我在香港的工作室受委托设计沙田城市公园之时。这个公园有10hm2的面积,是河岸的一个中央公园,为75万人的新城服务的一块再生的土地。在那时,20世纪80年代,我们认识到相关的资料非常之少,于是我发誓,一旦公园建成,我要写本关于城市公园的书。后来直到1998年我在曼尼托巴大学任教才开始写这本书。

《伟大的城市公园》一书,是基于西欧和北美一些重要的城市公园案例的研究。第一版出版于2001年,涵盖了20个公园,此书也出版了中文译版。第二版出版于2015年,共包含有30个公园,原有的20个加上10个较新的案例,如纽约的高线公园和阿姆斯特丹的文化公园。在两版中,公园均以尺度排序,而非建设地点或年代。第一版的一位评论者认为这有些随意,然而,我仍然坚持尺度是公园设计方法中的决定性要素。

那么“基于案例研究”是什么意思呢?我的意思是,针对同一个问题分析每一个公园,试图寻找其共有的经验,而这些经验在别处或许也有参考价值。因此,两版都对每一个公园进行了如下分析:

·历史,包括为何选定

·选定时期的场地条件

·负责设计和建设的主要人物

·公园的规划和设计

·促进公园发展的个人

·现在负责公园管理的机构

·当前的资金来源

·当前的使用程度—特别是游客数的记录

·公园内的犯罪率

·公园的计划

这篇文章总体遵循上述主题顺序展开。

历史—选定的原因

公园在欧洲最早是为了适应公众需要将皇家猎苑开放作为游憩之用而产生的。伦敦的海德公园据说是由查理一世(1625—1649年在位)大约于1635年开放的。查理二世大致在1660年整修开放了圣詹姆斯公园。德国慕尼黑的英国园,在1789年从军事保留区转换为公共的公园,是由于查尔斯·西奥多王子的指示,可能是受到法国革命的影响。1818年弗里德里希·威尔海姆三世援请彼得·约瑟夫·莱内重新设计柏林的蒂尔公园以供公众使用。这些迅速发展的对公园的需求亦反映在克里斯汀·凯·洛伦兹·赫希菲尔德(1742—1792)的著作里,她在1785年写道,“公园是为所有社会阶层提供游憩的场所,亦是道义的进步”[1]。作为对比的一个例子,北京的北海公园在1925年首次对公众开放。

早期的欧洲公园模式对于美国的公园发展有着很大的影响。浪漫的家长主义对于公园的选定有着相似的影响。首先在纽约,主要由安德鲁·杰克逊·道宁(1815—1852)和伙伴推动,他们特别重视公园带来的健康利益和“教化影响”,随后,衍生至遍及全国的发展中的工业城市。从弗雷德里克·洛·奥姆斯特德(1822—1903)的宣言到后来,自19世纪初起,城市公园为民众带来健康利益已经成为一贯的主题。近来,特别是由于西方社会日益增长的老龄化以及忙碌的人们对于健康设施的需求,公园作为简单锻炼和享受户外闲适时光的场所,正变得愈加重要。

欧洲和北美在20世纪初,公园从消极的休闲场所变为积极的游憩场所。公园盛行的实体形式如汉堡城市公园、塞维利亚的玛利亚路易莎公园、芝加哥格兰特公园等,这些公园从如画的田园模式(由莱内在柏林,帕克斯顿在伯肯黑德,道宁、沃克斯、奥姆斯特德在纽约所推动的模式)而演化,采取了明显的直线几何形式,显然配合了功能的目标。

20世纪后期的公园,有些是个人慈善的结果,如佩利公园,一个位于曼哈顿市中心的经典的口袋公园(1967年开放);有些是在之前的工业场地上建设的,如北杜伊斯堡景观公园(1994年开放),广东中山造船厂公园(2001年开放);有些是作为临近的房地产发展的催化剂而建设或重新设计的,如巴黎的安德烈-雪铁龙公园(1992年),贝西公园(1997年),伦敦的伊丽莎白女王奥林匹克公园(2012年夏季奥运会的场地)。

1 慕尼黑市中心的英国园南端的草坪。英国园作为德国第一个公共公园于1789年开放(英国园,慕尼黑)Lawns at southern end of Englischergarten with central Munich in background—opened in 1789 as the first public park in Germany (Englischergarten, Munich)

在21世纪初,被破坏的土地的再利用,如阿姆斯特丹的文化公园,以及工业废弃地的再利用,如纽约的高线公园,这两类逐渐愈加常见。同样的,有越来越多的机会去建设一些实际上是屋顶花园的公园,如多伦多的约克威尔公园;西雅图的高速公路公园;布莱恩特公园,其重新铺设的草地覆盖在临近的纽约公共图书馆的书库上;芝加哥的格兰特公园的北端的千禧公园和玛吉·戴利公园。最近,伯格就反对高速公路在美国穿越城区的问题发表了文章[2](这一问题的讨论始自1976年开放的高速公路公园)。许多高速公路如今已经建设了公园和公共空间。

原有的场地条件

配置为城市公园的土地通常“是些商业和住宅建筑不想要的用地,对于已建立的城市生活的格局并不是不可或缺的”[3]。这对于纽约中央公园来说确实如此,它在景观营造中是个重要的实践。同样地,在欧洲的许多前皇家公园,包括伦敦的圣詹姆斯公园和柏林的蒂尔花园,因排水和/或地质条件而阻碍了建设的开发。相似地,芝加哥的格兰特公园是通过倾倒废料到密歇根湖填湖造地而建设起来的,尤其是自1871年的芝加哥大火以来。肖蒙山丘公园曾是个石膏采石场、屠马场和垃圾场。而伦敦摄政公园在“二战”期间曾堆满建筑渣土,影响了它的排水系统。

伊丽莎白女王奥林匹克公园的主设计师—乔治·哈格里夫斯指出,“这个世纪的公园……近似于一个工程……位于困境地带,被废弃的、污染的、忽视的场地,或兼而有之……地形通常平坦,缺乏任何重要的植被或其他自然特征,却靠近城市中心”[4]。然而,在我们生活的时代,衰退的遗迹常引人注目,如北杜伊斯堡景观公园、贝西公园、高线公园等,许多人认为其场所的保护丧失了某些真实性而令人失望。拿2个中国的例子做对比,一个是广东11hm2的中山造船厂公园,另一个是上海17hm2的徐家汇公园(2002年开放)。造船厂公园由土人景观设计,其保留和呈现了克利夫兰的先见使得湖系的岸线大部分得以保护起来用于公共游憩。

2 在曼哈顿市中心由私人所有、修建和投资的口袋公园里的瀑布、树木和可移动的座椅(佩利公园,纽约)Waterfall, trees and moveable seats in the privately owned, built and funded pocket park in midtown Manhattan (Paley Park, New York)

3 会议中心和公园跨越美国5号洲际公路(高速公路公园,西雅图)Convention Center and park spanning US Interstate Highway 5 (Freeway Park, Seattle)

公园建设的主要人物

《伟大的城市公园》一书提及了大量无私的支持者,从赫希菲尔德到“高线之友”,他们不求回报地推动了公园的发展。他们中许多人只是简单的热心市民。也有很多重要的政治人物做出了主要的贡献。首先比如巴黎,拿破仑三世以及他麾下连续的塞纳省长乔治-欧仁·奥斯曼建设了整个公园和公共空间系统。随后,到20世纪末,政治对手密特朗总统—拉维莱特公园的推动者,和雅克·希拉克总统—安德烈-雪铁龙公园和贝西公园的推动者,争相建设21世纪最佳的巴黎的公园。

相似地,市长理查德·戴利坚定地支持将千禧公园纳入芝加哥格兰特公园,随后他又在附近建设了玛吉·戴利公园,以纪念他的夫人。在21世纪初,英国首相托尼·布莱尔与伦敦市长肯·利文斯通一起将夏季奥运会争取到了伦敦,并将新的生机引入下李谷(lower Lee Valley)。2008年的北京,这也是很明显的,奥运会作为城市长期改善的催化剂有着巨大的潜力,包括建设新的公园和景观设施。

同样值得注意的是,设计人员的连续性对于新公园建设的设计整体性而言是至关重要的。这在前景公园中十分明显,这个公园保持了比中央公园更统一的设计,沃克斯和奥姆斯特德一直持续为之设计,从1864年到1872年完成;克利夫兰对明尼阿波利斯的设计从1883年到1900年他去世;舒马赫为汉堡城市公园做设计从1910年到1933年;在曼海姆的路易森公园,豪斯特·瓦根菲尔德,1975年联邦园艺展的设计者,仍然在其后的40年间为经营者们提出建议;Latz+Partner事务所对北杜伊斯堡景观公园,凯瑟琳·古斯塔夫森对阿姆斯特丹文化公园,在其建成后许久仍对公园提出建议。大量的场地原有用途的参照,用以献给之前的造船工人。同样的,WAA事务所(Williams-Asselin-Ackaoui)设计的徐家汇公园其设计焦点在于一个保留下来的砖砌烟囱,这个烟囱以前控制了这个场地。

一个经验是来自霍勒斯·威廉·夏勒·克利夫兰的智慧,他的《关于明尼阿波利斯公园和园林路系统的建议》认为,“保护这些地区是必须的”,因为公园“在它们被占用或被索取价值之前,要使这些地带不被获得”[5]。

规划和设计

尽管建筑通常反映建设时期的时代思潮,而公园则往往反映了公园建设所在的场所。公园是它们所处的环境的在地创造,它们和环境有着共生的关系。它们必然是所在城市的不可或缺的一部分。然而它们也能从中分离,即从城市中逃离(特别是在18世纪)或作为城市的延伸(特别是在21世纪)。例如,纽约的中央公园,道格·布隆斯基(中央公园管理处前主任)描述其为“从城市生活撤退至风景”[6],它被设计为与周遭的城市形成彻底的对比。相反地,高线公园的设计原则之一是呈现穿过临近的哈德逊河、朝向周遭城市的风景。

土地经济学家约翰·克朗普顿,研究了公园对相邻地产价值的影响,指出“公园对于地产税重要影响的决定性因素是公园周长或边界影响的范围”[7]。纽约中央公园、旧金山的金门公园、阿姆斯特丹的冯德尔公园等公园的矩形证明了这一点,这些公园每一个都是设计作为房地产发展的焦点。对比摄政公园粗略的圆形,同样也为了房地产发展,特别是为了建筑师约翰·纳什设计的摄政台地,有着相对一块区域的最少周长。这可能是因为它原来是围篱以作为鹿苑,而圆形可以用最少量的围篱。与克朗普顿对地产价值的研究相应的是,亦有论断认为“如果人们更多地居住在公园附近,他们可能拥有更好的精神健康、更好的生理健康,以及更低的肥胖率……没有其他健康干预能给我们如此多的福利”[8]。

19世纪的“休闲场地”的设计深受田园式或如画式的先例的影响,如莱普顿和纳什在圣詹姆斯公园和摄政公园;帕克斯顿在伯肯黑德公园;莱内在蒂尔花园;沃克斯和奥姆斯特德在中央公园和前景公园;阿尔方德在巴黎;克利夫兰在明尼阿波利斯。这些设计总的来说基于尽量排除周围城市的原则,创造了水体、草地和树林的平衡格局,都设计为提供大范围的显然较为自然的景观。在20世纪初,有些公园如汉堡城市公园继续将这3种要素结合,尽管是用完全几何的布局。同样地,设计于20世纪30年代的阿姆斯特丹森林公园,亦由水体、草地和树林组成,是一种明显的荷兰范式。

可以认为城市公园有2个普遍的布局类型,一种是直线型的,不论是网格状的还是有轴线的;另一种是浪漫的或田园风格的。直线型的布局常常借用建筑师的灵感,如舒马赫主导的汉堡城市公园(市民公园的原型),玛利亚·路易莎公园,有林荫广场形成的网格;或网格化的公园,如巴黎贝西公园和拉维莱特公园。同样,阿兰·普罗沃设计的许多公园,包括安德烈-雪铁龙公园,都是具有“方向性的景观”,适应了周围的城市肌理。

另一种类型,浪漫的或田园风格的,是从莱普顿或纳什在伦敦圣詹姆斯公园和摄政公园的原型发展出来的。帕克斯顿在伯肯黑德采用了这种风格。这种风格也是沃克斯和奥姆斯特德的灵感来源之一。这也在一些案例中得以体现,如莱内对于蒂尔花园的重新设计,再如1975年德国联邦园艺展路易森公园的布局,8字形的环路环绕着一个湖,与圣詹姆斯公园的布局有所不同。在这些案例中,阿姆斯特丹的冯德尔公园,设计通过隐藏水体的尽头创造了一个更大的想象空间,形成了河流般的面貌。历史学家约翰·迪克逊·亨特认为“如画式超越了穿越风景的移动,超越了穿越思维的移动”[9]。这在伯肯黑德公园、中央公园、前景公园的马车道路系统得以体现。而环绕水体的步行道,比如在圣詹姆斯公园、摄政公园、冯德尔公园、路易森公园,这样的步行道是直接和安全的,同时又慢慢呈现了景观,逐渐展开景观的奥妙。

奥姆斯特德在1866年他与明尼阿波利斯公园委员会的一封信中建议:“享受公园的至佳景色应在步行中体验……要把那些乘马车来的人从车上吸引下来去步行体验。[5]”观赏中国的古典园林便是这样的方式,是在移动中的观赏,而非从一个地点观看。奥姆斯特德和沃克斯,像18世纪英国的“万能的布朗”,和20世纪美国的沃尔特·迪士尼一样,将周遭的环境,乡村的或城市的,排除在公园之外。然而近来,中央公园周围的建筑变得愈加明显,哥伦布圆环附近的高层住宅区在公园投下长长的阴影,其对于公园植被和游客的影响已引起了人们的关注。

环境

尽管一些公园把周遭排除在外,我在《伟大的城市公园》里讨论的要点之一是公园对周围环境做出直接回应的程度。这些公园反映了一种方法,它基于理解、阐释和表达独特的、固有的自然和文化特性。风景园林教授巴利·格林比将这种方法描述为“首先思考那里有什么,而不是像建筑师那样思考将什么放在那里”[10]。

在这一点上值得一提的是,约瑟夫·帕克斯顿,伯肯黑德公园的设计师,曾写给他妻子说他“走了至少30英里”(约48km)从而使自己能“掌控场地”[11]。同样地,奥姆斯特德被沃克斯邀请加入团队参加中央公园的设计竞赛,是因为他对场地的熟知。而阿兰·普罗沃,安德烈-雪铁龙公园大部分的设计者,说他到达场地时,他寻求“区分2种类型的场地:一种有主体,有精华,有灵魂,有某种特性,面对这样的场地,要谦逊;而另一种没有特殊的特质,强烈的干预是优点而非错误”[12],如位于巴黎拉德芳斯的狄德罗公园,就是一块完全建造出来的场地。

同样地,Latz+Partner事务所设计的北杜伊斯堡景观公园是如此地实用,拉茨回忆,在现场的阶段,拉索斯时时狐疑担心拉茨同事们的设计,挪揄道:“可你们什么都没做啊”[13]。这引发了这个争议性的问题,公园设计是否应该显得不可或缺或者说它们的人造属性是否应该显而易见。

持续性

风景园林师迈克尔·凡·瓦肯伯格认为“建造公园实际上是非常便宜的,而长久维护起来却是非常昂贵的”[4]。和这一观点一致,《伟大的城市公园》里许多公园的成功依赖于管理人员长期的服务和贡献,以及设计师的技巧和持续的投入。这个方面的代表人物包括:

爱德华·坎普—伯肯黑德公园1843—1891年的主管

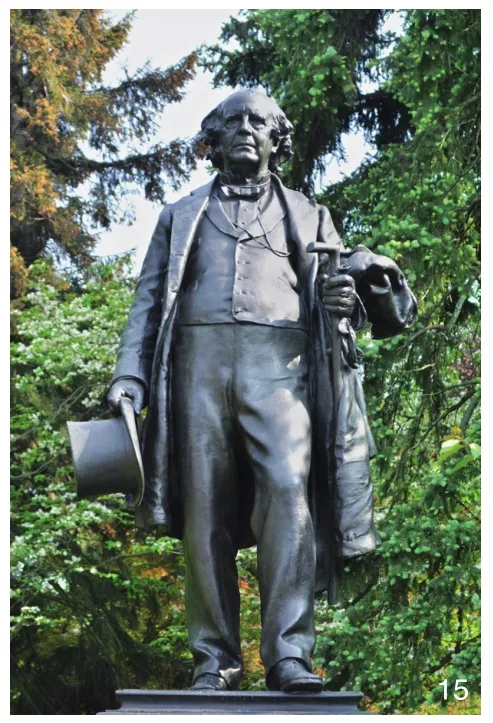

詹姆斯·斯特拉纳汉—前景公园1860—1882年的主管

约翰·麦克拉伦—金门公园1890—1943年的主管

塔帕·托马斯—前景公园1980—2011年的主任

丹尼尔·彼得曼—布莱恩特公园1980年至今的主管

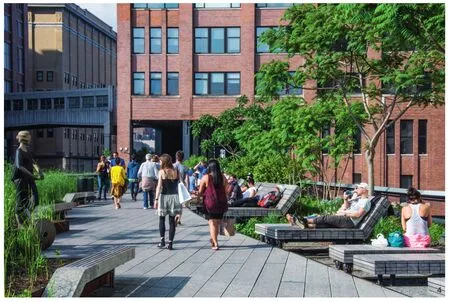

4 迪勒·冯·弗斯滕伯格晒台的行人和日光躺椅(高线公园,纽约)Pedestrian traffic and sunbeds on Diller von Fürstenberg Sun Deck (The High Line, New York)

5 人行天桥跨越约瑟夫·凯赛尔街,连接公园的2个区域(贝西公园,巴黎)Pedestrian bridge over Rue Joseph Kessel, linking two sections of the park (Parc de Bercy, Paris)

约阿希姆·克勒茨—路易森公园20世纪90年代到21世纪10年代的经理,任职合同规定在他管理期间公园的布局、功能或特征不能改变。

另外值得一提的是许多案例是近20年左右的,表明了西方国家的公园受益于较长期的管理稳定性和连续性。同时,越来越明显的是欧洲的公园,像美国的公园一样,仅靠公共拨款难以继续生存。正如凡·瓦肯伯格指出的,维护公园太贵了。拿伯肯黑德公园来说,除了因其历史状态和本身的设计质量,我将之收入《伟大的城市公园》第一版,还有就是为了说明特别是财政紧缩地区依靠地方拨款的公园的命运,其结果是不得不与法定托管的当地政府争取日常拨款。

另一个问题是政治上对于短期高影响力的项目的倾斜,如塞维利亚的都市阳伞,削减了玛利亚-露西亚公园替换树木的预算,仅仅是因为见效较慢。因此越来越多的欧洲和美国的城市公园,被迫去寻求其他收入来源,特别是通过举办舞台活动、特许经营、停车、其他直接收费项目,以及慈善捐赠和志愿计划。

尽管对于公园的公共投资有明显的下降趋势,而公园的使用却有着明显的上升趋势。假设,举办活动增加了对于完善公园的投资;投资于公园的完善吸引了更多的游客;有更多的游客使得人们感觉更安全;安全的公园吸引人们住在附近;对于有吸引力的公园周围的住房的需求提升了地产的价值,使得居民更可能投资于当地公园的维护和进一步的完善。游客数的总体上升也有助于更多的人在主要城市里集中居住,也有助于城市和公园的更好的运营。有些公园如巴塞罗那的奎尔公园,对游客如此有吸引力,故而城市对非居民开始收门票,如今,高迪设计的部分其门票收费7欧元。

连接

有观点认为公园规划正变得更有战略性,公园管理正变得更积极主动,并且更加市场导向。詹姆斯·科纳,高线公园的设计师,指出“为了努力提供较大的公园系统,可以漫步、骑车、跑步数英里,并且因其区域尺度和连接性而使生态系统繁荣,如今大尺度场地的更有力的连接、集合、连续的趋势更加明显”[4]。简而言之,公园越来越被视为城市景观设施的不可或缺的要素。

基于这种思考我曾于2017年6月在曼彻斯特进行演讲。基本的观点是虽然公园之前被视作孤立的绿色避难所,与周遭城市形成对比,它们现在被认为是“绿色广场”,对于未来城市极其重要。例如,巴黎的绿荫步道在1853—1969年曾是一条铁路,在1987—2000年间被转换成一条4.5km长的抬高的步行道。巴黎市政府也在积极地探索环城铁路的游憩潜力,这条铁路环绕巴黎中心,长达30km,靠近安德烈-雪铁龙公园,穿过了肖蒙山丘公园。

在《伟大的城市公园》一书里讨论的许多公园持续促进了生态的作用,特别是较大的公园,如金门公园,圣路易斯的森林公园,中央公园,阿姆斯特丹森林公园。阿姆斯特丹森林公园现在依然被认为参与到了“以游憩和自然保护为目标的生态管理”中[14]。更显著的是伊丽莎白女王奥林匹克公园的设计和管理,作为一个在起作用的景观,“将管理水位和洪水,控制河岸侵蚀,创造一系列的连接起来的栖息地,易于管理和维护”[15]。

《伟大的城市公园》一书总结了由于地球人口愈加城市化,城市公园可能变得愈加重要。公园作为自然景观的人工模拟而建立,意图与城市形成根本的对比。但有植物的公园现在更可能被视作后工业城市的生态和经济的不可或缺的要素。公园也将继续作为慰藉的场所,集会的场所,减轻创伤的场所,敬畏的场所,魅力的场所,逃避的场所,游玩的场所,人们可坐下来思考的场所。用杰弗里·杰里科的话来说,“提升人们出离日常生活”。公园将继续作为城市整体的一部分,以及人和其他物种的栖息地。

这导致了如下讨论,即城市公园是城市景观设施的最为重要的要素之一。这个讨论基于风景园林师总在寻求景观的链接,即城市景观的连接和连续。讨论可扩展到,将来风景园林师将必须在日益密集开发的城市中寻求更多实难发展的链接。这个讨论先以2个早期的伦敦公园为例,摄政公园(始于1811年)和圣詹姆斯公园(于1827年重新设计),通过波特兰大街和摄政大街连接,是景观作为基础设施的一个较早的例子。随后很快,在1829年,伦敦北部的多山的汉普斯特德荒野,在开发对其产生威胁之后,约翰·劳迪斯·劳登(1783—1843)提议设置环绕城市的“大都市的呼吸空间”的同心环。伦敦的方案反映了公园作为“城市之肺”的观点出现。这是早期对城市景观的作用的认识,认识到公园是城市物质的和精神的健康设施的一部分。

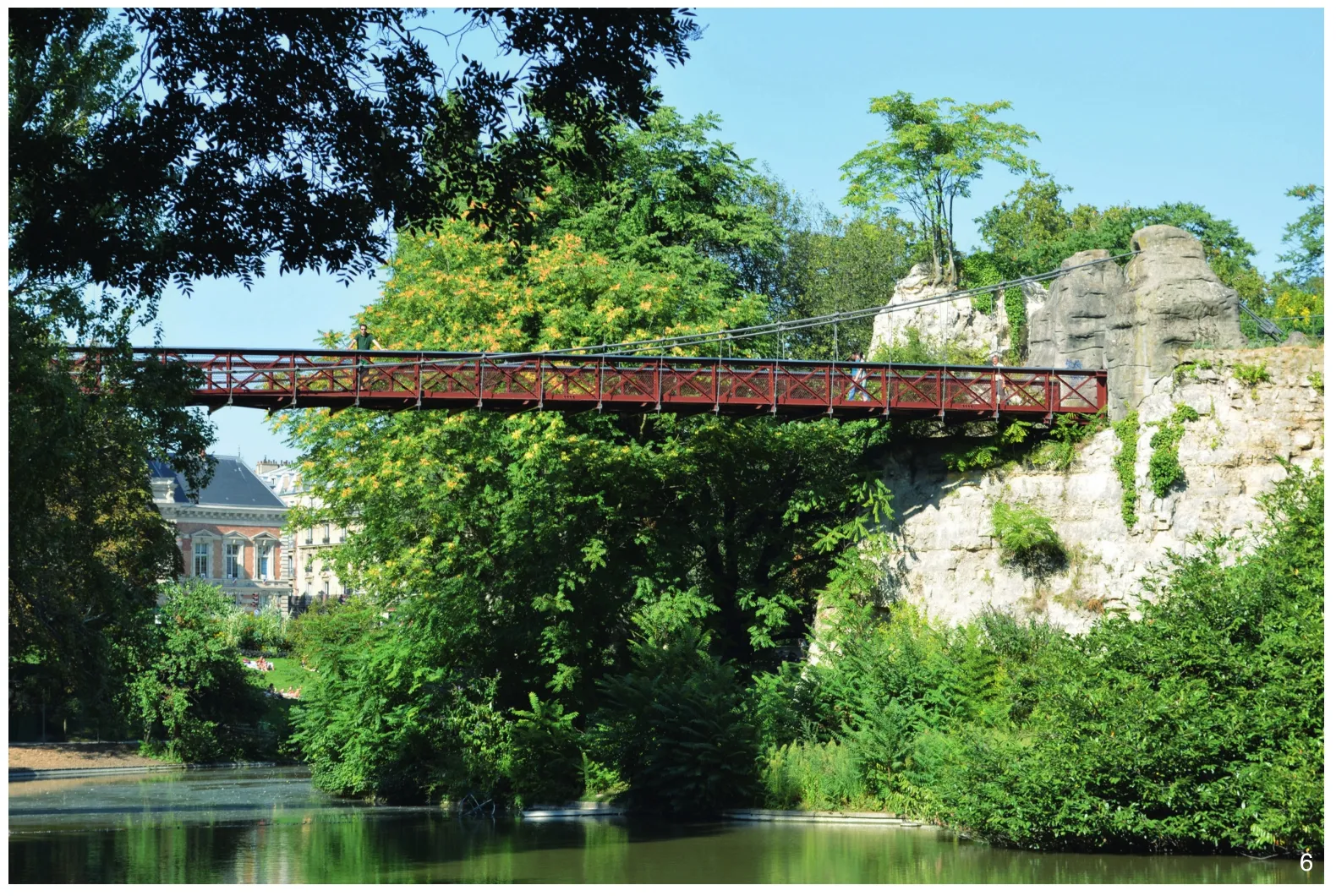

6 埃菲尔设计的步行桥通往残余的石膏孤岛(肖蒙山丘公园,巴黎)Eiffel-designed footbridge to residual island of gypsum (Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, Paris)

而与上述进行类比,值得一提的是拉维莱特公园设计竞赛的目标,描述公园“并不像肺而更像心脏”[16],它会再造城市那一部分的活力,激发和调控其他的所有要素。相似的故事支撑了拿破仑三世和奥斯曼的巴黎的规划和设计,首先,他们将巴黎边缘2个大的皇家猎苑—文森森林(东边)布洛涅森林(西边)转换为公众使用。然后他们开发了促进健康(也易于管辖)的林荫大道模式,建立了公园和植被空间的网络,设计为促进所有的“循环”—交通,空气和人们的呼吸。

相似的案例还包括有着技术派生的法国式曲线的肖蒙山丘公园(1864年)。“肖蒙”的意思是光秃的山丘,这是对先前状况的一种反映,这里之前是石膏采石场、屠马场(屠宰老马)、垃圾场,甚至有公开处决的绞刑架。如今和附近的拉维莱特公园一起,它是新区的“心脏”……如潮的人们在这里欣赏城市的全景,也同时享受从城市的逃离。经过一段时间以后,它可能会通过城市环线,与巴黎其他公园连接起来,比如在城市西南部的安德烈-雪铁龙公园,这个环线是一处潜在的绿色基础设施,可与正在发展的美国亚特兰大35km长的环行线相提并论。

我们可以看到将城市公园引入北美的相似的模式,这始于中央公园,它建于多石的土地,远离那时高价的曼哈顿海滨……如今却呈现了世界上最昂贵的景观。沃克斯和奥姆斯特德的草坪规划(1857—1858年)是基于树林、水体和草地的田园模式,最早在伯肯黑德公园(1845年)出现,被多石场地的中央公园采用。这种模式在前景公园(1866年)应用十分完美,其外围有防护性的堤岸环绕。

在前景公园之后,奥姆斯特德和沃克斯发展了公园的连接,正如他们设计了从前景公园到布鲁克林海滩的公园路,他们设计的林荫大道穿越了纽约布鲁克林地区。奥姆斯特德的这种连接手法发展到顶峰的是,9个公园组成了波士顿和布鲁克莱恩的“翡翠项链”(1878—1895年)。这条项链主要顺应了一条自然的排水廊道,证明了确认和保护城市地区的自然财产的重要性。1871年大火之后的芝加哥公园系统,奥姆斯特德和他的同事克利夫兰对其发展做出了贡献,包括著名的湖滨路和其他公园以及林荫大道系列。随后丹尼尔·伯纳姆和爱德华·贝纳特所做的芝加哥规划(1909年)是美国城市美化运动的闪光点。格兰特公园的中心在艺术学院的白金汉喷泉,位于重新设计的城市的轴线上,是绿色基础设施作为再建城市的焦点的一个典例。

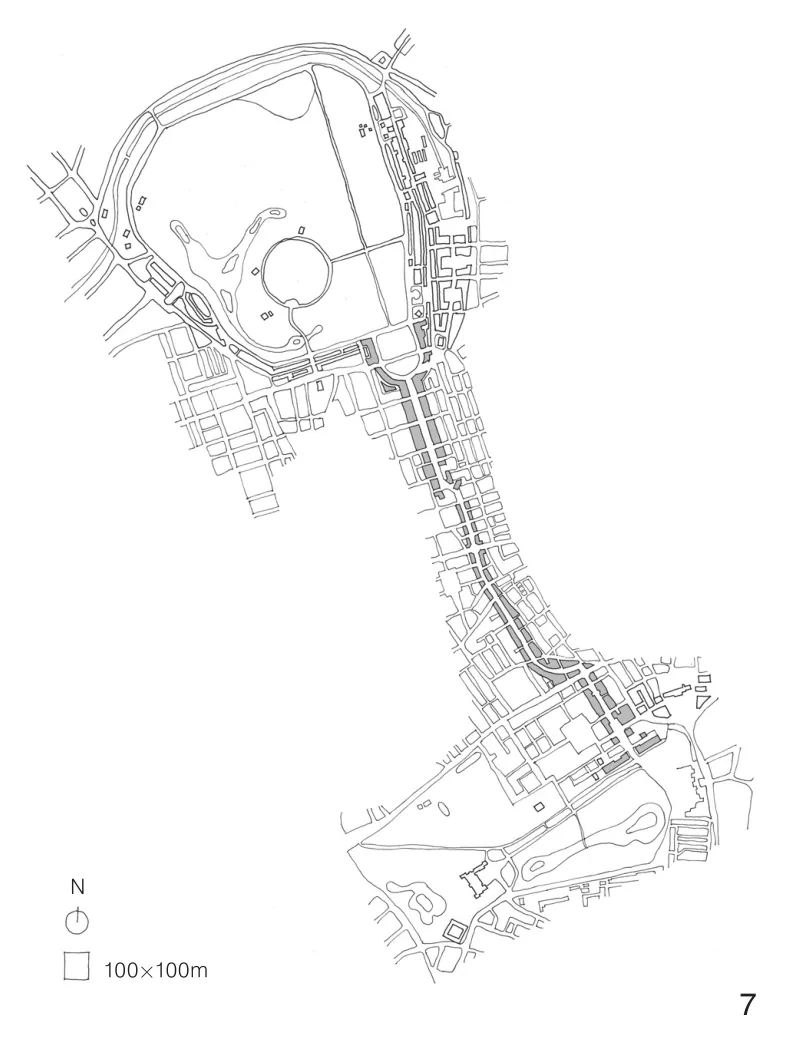

7 平面图显示了2个皇家公园以及它们之间沿着波特兰大街和摄政大街的连接(摄政公园和圣詹姆斯公园平面图,伦敦)Plan showing the two Royal Parks and the linkage between them along Portland Place and Regent Street(Plan of Regent’s and St James’s Parks, London)

如前所说,克利夫兰从芝加哥到规划明尼阿波利斯公园系统,应用了奥斯曼在巴黎的经验和大火后的芝加哥的经验,创建了一个最佳的范例,即,在开发可及之前,在私有化之前,在阻止公众进入之前,连接景观基础设施。到今天,在众多湖泊中仅有一个湖—雪松湖,有私人的岸线。并且,像美国众多的城市一样,特别是内陆城市,景观基础设施穿越市区的高速公路已被重新连接起来,如跨越94号州际公路的桥,连接了明尼阿波利斯雕塑公园和洛林公园,有效地连接了明尼阿波利斯中央公园。另一个例子是互相连接的景观基础设施,加拿大温哥华斯坦利公园的海堤,约405hm2的“陷阱荒野”,这个城市渴望2020年成为“世界上最绿色的城市”。最重要的一点是海堤连接到城市范围的绿道系统,这是由规划师哈兰德·巴塞洛缪于1926年做出的规划。虽然这些理念需花费漫长时间去实现,但必须去发现机会并尽早践行。

同时,在欧洲,阿姆斯特丹森林公园,1930年代制造工作机会的项目(也有重要的森林、水体和草地的区域),仍然在南向扩张直达申克尔森林,在阿姆斯特芬的体育公园和网球中心介入之后北向将纽威米尔湖纳入。继续对连接进行时间的纵览,阿伯克龙比和佛朔所做的始于1943年的伦敦郡规划证明了景观作为基础设施的原则,但一个快速郊区都市化(suburbanization)、都市人口收缩和公园衰退的年代,于“二战”之后在欧洲和北美大部分地区到来。从2000年开始,城市中心收缩已经有些开始反转,但欧洲和北美仍然处于一个相对低密度的都市蔓延的时代[17]。

“二战”之后,新的公园发展较慢,如纽约的佩利公园,建设很慢而且是私人所有。但自一些项目后,情况有了反转,如哈普林先驱性的高速公路公园,穿越西雅图市中心5号州际公路建设。2017年获得ASLA 全国奖的位于达拉斯市中心的柯林德沃伦公园(综合设计奖的最佳设计奖,译者注),建在伍道尔罗杰斯高速路,是一个新近的更激动人心的案例,一个连接先前被分割的社区的景观基础设施的极佳案例。对于连接的投入在所有尺度都是明显的,如巴黎贝西公园的2个区域之间的桥,还有伊丽莎白女王奥林匹克公园内大量的桥,公园南向与泰晤士河的连接,以达成与42km长的李谷区域公园的连接(这是由阿伯克龙比和佛朔在1943年对伦敦郡做的规划中提出的)。

结语

《伟大的城市公园》一书讨论了一系列的高成本高知名度的项目,如纽约的布莱恩特公园,多伦多的约克威尔公园,芝加哥格兰特公园内的千禧公园,北杜伊斯堡景观公园,阿姆斯特丹文化公园,他们都是处于极困难的地带,不是有毒性的土壤就是有一堆设施。像文化公园一样,他们仍然寻求首先解决内在的(或承继的)场地问题,去与环境和背景呼应,然后发展与更广阔的场景的联系。

而且,即使是高成本、高知名度、高维护,高线公园依然试图扩展和提供与过去的视觉链接以及与城市的视觉链接,它是城市不可分割的一部分。如科纳所说,高线公园是一个致力于“寓多于少”的典例。这对中国尤其重要,因为中国在接下来15年的城市化进程中,将产生2.3亿新的城市居民①。

高线公园是如此受欢迎,以致高峰时段需得限制游客数量。而且,如前提到的,奎尔公园的史迹部分现在对非居民需要收门票。对公园日益增长的巨大需求显然十分普遍,不论是居民,还是游客。可能这种需求最显著的发展是发生在此书2001年和2015年两次出版之间。这影响了2015年版本的案例选择,如在布莱恩特公园,每个午餐时段都会计算游客量,包括女性比例,这基于高比例的女性游客意味着公园更安全的理论。简而言之,正如赫希菲尔德在200年前他的《园林艺术理论》一书中谈过对于公园的需求,这一论点如今在欧洲、在北美……在中国,依然有效。

注释 (Notes):

①引自王向荣教授于2017年6月22日在英国曼彻斯特城市大学举行的英国皇家风景园林学会年会上的“Integrated Places: Where People and Nature Meet”主题演讲。It was quoted from a series of keynote lectures under the heading “Integrated places: where people and nature meet”, delivered by Prof. WANG Xiangrong at the Landscape Institute of the United Kingdom Annual Conference in Manchester Metropolitan University,Manchester, England on 22 June 2017.

②图1、3、6、8~9、13~15、20由阿兰·塔特摄;图2、5、10、18~19由Marcella Eaton摄;图4、16~17由Belinda Chan摄;图7由Peter Siry摄;图11由Peter Neal摄。Figure 1, 3, 6, 8-9, 12-15, 20 photoed by Alan Tate; Figure 2, 5,10, 18-19 photoed by Marcella Eaton; Figure 4, 16-17 photoed by Belinda Chan; Figure 7 Drawn by Peter Siry; Figure 11 photoed by Peter Neal.

:

[1] SCHMIDT H. Plans of Embellishment: Planning Parks in 19th Century Berlin[J]. Lotus International, 1981, 30: 83.

[2] BERG N. Goodbye Highways[J]. Landscape Architecture, 2017, 107(2): 74-81.

[3] SUTTON S B. Civilizing American Cities: Frederick Law Olmsted Writings on City Landscapes[M]. New York: Da Capo Press, 1971: 11.

[4] Dialogues[J]. Landscape Architecture, 2009, 99(10): 56-65.

[5] WIRTH T. Minneapolis Park System 1883-1944: Retrospective Glimpses into the History of the Board of Park Commissioners of Minneapolis, Minnesota and the City’s Park, Parkway and Playground System[M]. Minneapolis: Board of Park Commissioners, 1945: 38.

[6] BLAUNER A. Central Park: An Anthology[M]. New York /London: Bloomsbury, 2012: 213.

[7] CROMPTON J L. The Impact of Parks and Open Spaces on Property Values and the Property Tax Base[M]. Ashburn,Virginia: National Recreation and Park Association, 2000: 11.

[8] City Parks Alliance. Cityparksalliance[EB/OL]. (2017).org/action-center/city-parks-americas-new-infrastructure.

[9] HUNT J D. The Influence of Anxiety[M]//CARR E,EYRING S, WILSON R G. Public Nature: Scenery, History,and Park Design. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2013: 13-26.

[10] GREENBIE B. Restoring the Vision[J]. Landscape Architecture, 1986, 76(3): 54-7.

[11] COLQUHOUN K. 'The Busiest Man in England': A Life of Joseph Paxton, Gardener, Architect and Victorian Visionary[M]. Boston: David R. Godine, 2006: 14.

[12] PROVOST A. Interview with Gérard Mandon[J]. Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes, 2002,23(2): 208.

[13] DIEDRICH L. No politics, no park: the Duisburg-Nord model[J]. Topos, 1999(26): 69-78.

[14] Stedelijk Beheer Amsterdam. Amsterdamse Bos:Visitors' Information on Forestry Practice[Z]. 1994.

[15] HOPKINS J, NEAL P. The Making of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park[M]. Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 2013: 188.

[16] BALJON L. Designing Parks[M]. Amsterdam:Architectura & Natura Press, 1992: 39.

[17] OSWALT P. Atlas of Shrinking Cities[M]. Ostfildern:Hate Cantz, 2006.

(编辑/王一兰)

Introduction

My professional interest in city parks was piqued when the office that I was running in Hong Kong was commissioned to design Sha Tin Town Park—a 10-hectare riverside central park on reclaimed land for a new town planned to accommodate 750,000 inhabitants. Back then,in the 1980s, we realised that there was relatively little literature on the subject and I vowed that,once the park was f i nished, I would write “a book about parks”. Writing that book had to wait until I took up an academic position at the University of Manitoba in 1998.

This becameGreat City Parks,a case-studybased examination of some significant urban parks in western Europe and North America. The first edition, published in 2001, covered twenty parks. It was also published in Chinese. The second edition, published in 2015, covered thirty parks—the original twenty updated plus another ten—including some more recent ones like the High Line in New York and the Westergasfabriek in Amsterdam. In both editions the parks were ordered by size—rather than by location or by age.One reviewer of the first edition suggested that this was a somewhat random basis. Nevertheless, I maintain that size is a principal determinant of the approach to park design.

And what do I mean by “case-study-based”?I mean looking at the same issues for each park in order to try and identify common lessons that might be relevant elsewhere. Accordingly, both editions examined, for each park:

·history including the reasons for their designation

·condition of the site at the time of designation

·principal figures responsible for their design and establishment

·planning and design of the parks

·individuals responsible for their development

·organizations responsible for their current management

·current sources of funding

·current use levels—particularly records of numbers of visitors

·crime levels in the parks

·plans for the park.

This essay generally follows that order of topics.

History:Reasons for Designation

Public parks in Europe were first created in response to demand from the public to use royal hunting parks for recreation. Hyde Park in London is said to have been opened by King Charles I (reigned 1625—1649) in about 1635,and King Charles II “seems to have” opened St James’s Park to the public at the Restoration in 1660. The Englischergarten in Munich, Germany was converted from a military reserve to a public park in 1789—on the instruction of Prince Charles Theodore, probably influenced by the French Revolution. In 1818 Peter Joseph Lenné was instructed by Friedrich Wilhelm III to redesign the Tiergarten in Berlin for public use. This burgeoning demand for parks was also ref l ected in the writings of Christian Cay Lorenz Hirschfeld (1742—1792),who wrote in 1785 about them as “places of recreation and moral improvement for all social classes”[1]. By comparison, Bei Hai Imperial Park in Beijing was f i rst opened to the public in 1925.

Early European public park models had a strong influence on park development in the United States. There was a similar strain of romantic paternalism underlying the designation of parks, first in New York—promoted primarily by Andrew Jackson Downing (1815—1852)and associates, particularly with respect to their health benefits and “civilizing influences”—and subsequently in growing industrial cities across the country. The human health benef i ts of urban parks has been a consistent theme since the early nineteenth century—from the pronouncements of Frederick Law Olmsted (1822—1903) onward.More recently, and particularly as a result of the demands on health services from an increasingly ageing and under active population in the western world, the role of parks as places for simple exercise and for spending restful time outdoors has become increasingly important.

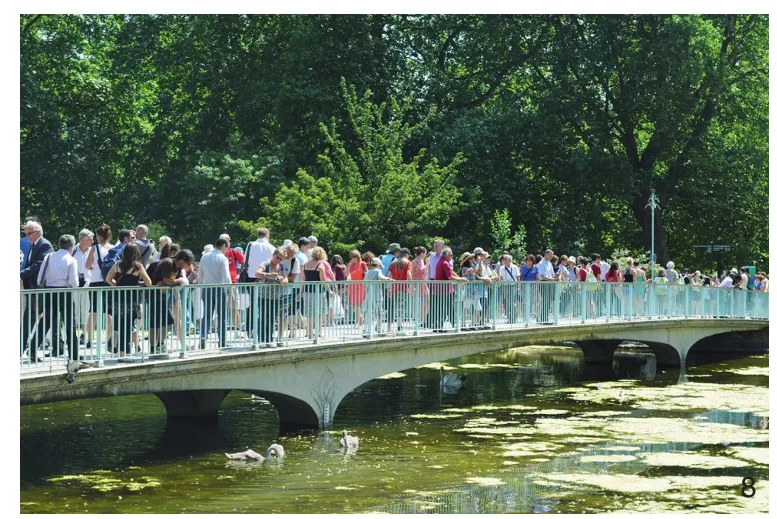

8 在湖中心步行桥上的游客(圣詹姆斯公园,伦敦)Visitors on footbridge at centre of the lake (St James’s Park, London)

9 库策湖上的始自1975年联邦园艺展的小游艇(路易森公园,曼海姆)Gondolettas from 1975 Bundesgartenschau on the Kutzerweiher Lake (Luisenpark, Mannheim)

10 奥运会期间在李河旁的湿地剧场(伊丽莎白女王奥林匹克公园,伦敦)Wetland bowl alongside the River Lee during Olympic Games (Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, London)

During the early twentieth century in Europe and in North America, parks changed from being places of passive leisure to being places of active recreation. The predominant physical form of parks such as the Hamburg Stadtpark, the Parque María Luisa in Seville and Grant Park, Chicago,evolved from the picturesque pastoral model promoted by Lenné in Berlin, by Paxton at Birkenhead and by Downing, Vaux and Olmsted in New York, to adopting a distinctly rectilinear geometry and to accommodating distinctly functional purposes.

Later twentieth-century parks included some that were a result of personal philanthropy,like Paley Park the quintessential pocket park in Midtown Manhattan (opened in 1967); many that were created on former industrial sites, like the Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord (opened in 1994)and, in Guangdong Province, the Zhongshan Shipyard Park (opened in 2001); and some that were created or re-designed as catalysts for adjacent real estate developments such as Parc André-Citroën (1992) and Parc de Bercy (1997) in Paris and, and Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in London, site of the 2012 Summer Olympic Games.

In the early 21st century, re-use of damaged sites like the Westergasfabriek in Amsterdam and industrial remnants like The High Line in New York, became increasingly common. Equally, more and more opportunities have been taken to create what are, effectively roof gardens—including Village of Yorkville Park in Toronto; Freeway Park,Seattle; Bryant Park with its re-laid lawn overlying storage stacks of the adjacent New York Public Library, and Millennium and Maggie Daley Parks at the northern end of Grant Park, Chicago. The current extent of the fightback against freeways through urban areas in the United States (which started with Freeway Park, opened in July 1976) is documented by Berg[2]. Many of them have been covered by parks and public spaces.

Original Site Conditions

Land allocated for urban parks has often been“some site undesirable for commercial or residential buildings, and in no way integral to established patterns of city life”[3]. This was particularly true of Central Park—which was a major exercise in landscape creation. Equally, many of the former royal parks in Europe, including St James’s Park in London and the Tiergarten in Berlin, suffered from drainage and/or geological conditions that precluded built development. Similarly, Grant Park,Chicago was created by dumping waste, particularly from the “Great Fire” of 1871, into Lake Michigan;the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont was a gypsum quarry and then a knackers’ yard and a garbage dump, and Regent’s Park in London accommodated building rubble during World War II, impacting its drainage.

George Hargreaves, principal designer of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, noted that“parks in this century … almost to a project … are located on distressed sites—abandoned, polluted,neglected, or all three … often f l at, devoid of any significant vegetation or other natural features,yet close to city centers”[4]. Nevertheless, we live in an era that is drawn to decaying relics—an era in which many people regard the conversion of places like the Landschaftspark, Parc de Bercy and the High Line into parks as lamentable losses of something authentic. Two comparable examples in China are the eleven-hectare Zhongshan Shipyard Park in Guangdong province and the seven-hectare Xujiahui Park in Shanghai (opened in 2002). The shipyard park, designed by Turenscape, retains and presents numerous references to the site’s former use, and is dedicated to former shipyard workers.Equally, the focal point of the design by WAA Inc.(Williams Asselin Ackaoui) for Xujiahui Park is the retained chimney from a brickworks that used to occupy the site.

One of the lessons from this is the wisdom of Horace William Shaler Cleveland’sSuggestions for a System of Parks and Parkways for the City of Minneapolisabout “securing of the areas that are needed” for the parks “before they become so occupied or acquire such value as to place them beyond reach”[5]. Cleveland’s foresight led to the majority of the shoreline of the Chain of Lakes being protected for public recreation.

Principal Figures in the Establishment of Parks

Great City Parksidentified numerous altruistic advocates from Hirschfeld to the Friends of the High Line, who promoted parks for little or no personal return. Many of them were simply concerned citizens. There have also been some significant political figures who have made major contributions. Paris, for instance, had, f i rst,Napoléon III and his relentless Prefect of the Seine Georges-Eugène Haussmann producing an entire system of parks and open spaces. Then,towards the end of the twentieth century, political adversaries President Francois Mitterand—promoter of Parc de la Villette—and Jacques Chirac—promoter of Parc André-Citroën and Parc de Bercy, vied to produce the definitive Parisian park for the twenty-f i rst century.

Similarly, Mayor Richard M. Daley was a determined advocate for the addition of Millennium Park to Chicago’s Grant Park—followed by the adjacent Maggie Daley Park, in memory of his wife. And early this century British Prime Minister Tony Blair worked closely with the first Mayor of (Greater) London, Ken Livingstone to bring the Summer Olympic Games to London and to bring new life to the Lower Lee Valley.And it is evident from the Beijing in 2008 that the Games have huge potential as a catalyst for longterm urban improvements, including new parks and landscape infrastructure.

It is also noteworthy that continuity of design personnel is critical for design integrity in the construction and establishment of new parks.This was evident at Prospect Park—which remains a more unified design than Central Park—with Vaux and Olmsted being retained from 1864 until completion of the design in 1872; in Cleveland’s proposals for Minneapolis from 1883 until his death in 1900; in Schumacher’s involvement with the Hamburg Stadtpark from 1910 to 1933; in the Luisenpark in Mannheim, where Horst Wagenfeld,designer of the 1975 Bundesgartenschau, was still advising the managers forty years later, and at the Landschaftspark and Westergasfabriek, where designers Latz + Partner and Kathryn Gustafson,respectively, maintained an overview long after construction was completed.

Planning and Design

11 世界上第一个公众投资的公园里的护堤、草地和树林(伯肯黑德公园,默西塞德)Mounds, meadows and trees in the first publicly-funded park in the world (Birkenhead Park, Merseyside)

12 格兰特公园西北部的4.7亿美元的公园区域(千禧公园,芝加哥)US$ 470-million park area at northwest of Grant Park(Millennium Park, Chicago)

13 从水塔和天文馆开始的公园主轴线(城市公园,汉堡)Main axis of the park from the Water Tower / Planetarium (Stadtpark, Hamburg)

14 从5号高炉看过去的以前的钢结构和新近栽植的树木(景观公园,北杜伊斯堡)Former steelworks and recent tree planting seen from Blast Furnace #5 (Landschaftspark, Duisburg-Nord)

Whereas buildings tend to ref l ect the zeitgeist(spirit and/or fashion) of the time in which they are built, parks reflect the places in which they are built. Parks are earth-bound creatures of their surroundings. They have symbiotic relationships with their settings. They are inevitably an integral part of the city in which they are set … and yet they can also be set apart from it—caught between being escapes from the city (particularly in the eighteenth century) and extensions of it(particularly in the twenty-first century). By way of example, Central Park, New York, described by(former President of Central Park Conservancy)Doug Blonsky as “a scenic retreat from city life”[6]was conceived as a complete contrast to the surrounding city. Conversely, one of the principles driving design of The High Line was the presentation of views outward to the surrounding city and across the adjacent Hudson River.

Land economist John Crompton, addressing the impact that parks have on adjacent property values, noted that “a determining factor of the magnitude of a park's impact on the property tax base is the extent of the park's circumference or edge”[7]. This is demonstrated by the rectangular shape of Central Park, of Golden Gate Park, San Francisco and of the Vondelpark, Amsterdam—each of which was designed as a focus for real estate development. By contrast the roughly circular form of Regent's Park—also the focus of property development, particularly architect John Nash’s Regency terraces—has the least possible edge for the enclosed area. This was probably because it was originally fenced-in as a deer park—and a circle would require the least amount of fencing.Parallel with Crompton’s studies of property values,it has also been asserted that “when there are higher concentrations of people who live closer to a park they are more likely to have better mental health,better physical health, lower levels of obesity …there’s no other health intervention that can give us those sorts of benef i ts”[8].

Designs for nineteenth-century “Pleasure Grounds” were strongly influenced by the pastoral/picturesque precedents established by Repton and Nash in St James’s and Regent’s Park; by Paxton at Birkenhead Park; by Lenné in the Tiergarten; by Vaux and Olmsted in Central and Prospect Parks; by Alphand in Paris, and by Cleveland in Minneapolis. These designs were generally based on the principle of excluding the surrounding city as far as possible and creating balanced compositions of water, pasture and woodland, all arranged to provide sweeping views of apparently natural scenery. In the early twentieth century, parks like Hamburg’s Stadtpark continued to combine these three elements—albeit in strictly geometric layouts. Similarly,the Amsterdamse Bos, designed in the1930s, is composed of water, pasture and woodland in a distinctly Dutch model.

It can be argued that there are two generic types of layout for city parks—rectilinear,whether gridded or axial—and the romantic /pastoral. The rectilinear layouts are often building architect inspired—like the Schumacher-led Hamburg Stadtpark (the prototypical Volkspark)the Parque María Luisa—with its grid of shaded glorietas or the gridded Parc de Bercy or Parc de la Villette in Paris. Equally, many Allain Provostdesigned parks—including Parc André-Citroën—are “directional landscapes”, adapted to the surrounding urban grain.

The other type—the romantic/pastoral model—derived from the Repton/Nash prototypes at St James’s and Regent’s Parks in London and picked up by Paxton at Birkenhead—became one source of inspiration for Vaux and Olmsted. This is also demonstrated in examples like Lenné's redesign for the Tiergarten or the layout of the Luisenpark for the 1975 Bundesgartenschau, with a f i gure-of-eight circuit around a lake comparable to the layout of St James’s Park. In these examples,and in Amsterdam’s Vondelpark, the designs create an illusion of greater space by concealing the ends of water bodies and giving them a riverine appearance. Historian John Dixon Hunt argued that the “picturesque was above all about movement,movement through a landscape, and the movement of the mind”[9]. This is demonstrated in the carriage routes around Birkenhead, Central and Prospect Parks. And the pedestrian circuits around the water bodies in St James’s Park and Regent’s Park, and in the Vondelpark and Luisenpark, are direct and safe at the same time as presenting views that are revealed slowly and with unfolding mystery.

Olmsted suggested, in a letter to the Minneapolis Park Commission in 1866, that“enjoyment of the best scenery of the park should be had from its walks … to draw many who will come to it in carriages to leave them and take walking exercise”[5]. There is a parallel here with the modes of viewing Classical Chinese gardens—through viewing in movement (as opposed to viewing from a single position). Olmsted and Vaux, like Capability Brown in eighteenth-century Britain and Walt Disney in the twentieth-century in the United States, were determined to exclude the surrounding landscape—rural or urban—from their parks.Latterly, however, surrounding buildings have become increasingly obvious around Central Park—to the extent that high-rise residential blocks around Columbus Circus has aroused concern about the effect on vegetation and visitors of long shadows across the park.

15 詹姆斯·斯特拉纳汉雕像,前景公园1860—1882年的主管(前景公园,布鲁克林,纽约)Statue of James Stranahan, Commissioner for Prospect Park from 1860 to 1882 (Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York)

16 从安戴尔拱门望向长草坪(前景公园,布鲁克林,纽约)View through Endale Arch to the Long Meadow (Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York)

Context

Despite this exclusion of their surroundings,one of the strongest points to emerge inGreat City Parksis the extent to which the parks are a direct response to their context. They ref l ect an approach based on comprehension, interpretation and expression of their unique and intrinsic natural and cultural characteristics. This reflects an approach that landscape architecture professor Barrie Greenbie described as thinking “f i rst of what is there,rather than, as architects tend to think, in terms of what one can put there”[10].

It is worth noting in this connection that Joseph Paxton—the designer of Birkenhead Park—wrote to his wife that he had “walked at least thirty miles” to make himself “master the locality”[11]. Equally, Olmsted was invited by Vaux to join his team for the Central Park competition for because of his intimate knowledge of the site. And Allain Provost, designer of the largest part of Parc André Citröen, commented that in his approach to individual sites he sought to“distinguish between two types of site: those that have a body, have marrow, have a soul, a certain character, in which case it’s better to be moderate,and those which have no special interest and where strong intervention is a virtue and not a fault”[12]—like Parc Diderot, on completely made ground just off La Défense in Paris.

Similarly, the Latz + Partner’s design for the Landschaftspark “was so pragmatic, Latz recalls,that during the workshop phase on site Lassus would look over the shoulders of Latz’s co-workers and tease: ‘But you aren’t doing anything’”[13]. This begs the challenging question of whether park designs should appear inevitable or whether their artif i ciality should be self-evident.

Continuity

Landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh commented that “it’s actually incredibly inexpensive to build a park, and it’s incredibly expensive to care for it in perpetuity”[4]. In line with this comment,many of the parks examined inGreat City Parkshave been as reliant for their success on the dedication and long service of their managers and superintendents as on the skill and continued involvement of their designers. Figures who stand out in this respect include:

17 在绵羊草地附近的岩石露头(中央公园,纽约)Rock outcrop near the Sheep Meadow (Central Park, New York)

·Edward Kemp—Superintendent of Birkenhead Park from 1843 to 1891

·James Stranahan—Commissioner for Prospect Park from 1860 to 1882

·John McLaren—Superintendent of Golden Gate Park from 1890 until 1943

·Tupper Thomas—Prospect Park Administrator from 1980 to 2011

·Daniel Biederman—who has been involved with Bryant Park since 1980

·Joachim Költzsch—Manager of the Luisenpark between the 1990s and 2010s, under a contract of employment that stipulates no alterations to the layout, function or character of the park.

It is also worth noting that many of these examples are from the last twenty or so years,suggesting that parks in the western world have been enjoying one of their longer periods of managerial stability and continuity. At the same time it has become increasingly clear that European parks, like US parks, can no longer survive on public funds alone. As Van Valkenburg noted, they are expensive to cater for. Taking Birkenhead Park as an example, apart from its historic status and intrinsic design qualities, I included it in the first edition ofGreat City Parksto illustrate the fate of locally-funded parks—particularly in financially poorer areas—that have to compete with legally mandated local government services for their day-today funding.

Another issue in this connection is political preferences for short-term high-impact projects—like the Metropol Parasol in Seville—whereas cutting funds for tree replacement in Parque María-Luisa will only manifest itself relatively slowly.So city parks in Europe as well as the United States have been increasingly obliged to seek other sources of income—particularly through staging of events, through concession franchises,through car parking and other direct charges, as well as through charitable giving and volunteer programs.

While there has been a clear pattern of falling public investment in public parks, there has also been a clear pattern of rising park use.Hypothetically, staging events raises funds that can be invested in park improvements; investing in park improvements attracts more visitors; having more visitors makes people feel safer; safer parks attract people to live near them; demand for housing near attractive parks raises property values, and makes residents more likely to invest in the maintenance and further improvement of their local park.The general rise in visitor numbers can also be attributed to more people living centrally in major cities, and to better marketing of cities and/or their parks. And then there are places like Park Güell in Barcelona, which has become so attractive to tourists that the city has imposed an entry charge for non-residents, currently €7, to the original Gaudí-designed section.

Connections

It can be argued that park planning is becoming more strategic, and that park management is becoming more proactive and more market-oriented. James Corner, designer of the High Line, noted that “the thrust today is clearly toward a more emphatic connection, assembly,and continuity of large-scale sites in an effort to provide larger park systems where one can walk,cycle, and run for miles and where ecosystems can thrive because of regional scale and connectivity”[4].In short, parks are increasingly seen as integral components of urban landscape infrastructure.

This kind of thinking underpinned a talk that I gave in Manchester in June 2017. The fundamental argument is that whereas parks were previously seen as isolated green refuges that contrasted with the surrounding city, they are now regarded as “green squares” that are critical to the future of the city. For instance, the Promenade Plantée in Paris—a railway from 1853 to 1969,was converted between 1987 and 2000 into a 4.5 kilometre-long elevated walkway. The Ville de Paris has also been actively exploring the recreational potential of the 30-kilometre Petite Ceinture rail line that circles central Paris, running close to Parc André-Citroën and through the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont.

Many of the parks examined inGreat City Parkscontinue to promote their ecological credentials—particularly larger parks like Golden Gate Park, Forest Park in St Louis, Central Park and the Amsterdamse Bos. The Bos is still seen as being engaged in “ecological management for recreation and nature conservation purposes”[14]. More emphatic has been the design and management of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park as a working landscape that will “manage water levels and flooding, limit bank erosion, create a series of connected habitats, and ensure ease of management and maintenance”[15].

Great City Parksconcluded that city parks are likely to become increasingly important as the earth's human population becomes more urbanised.Parks were instituted as manufactured simulacra of natural landscapes. They were intended to be complete contrasts to cities. But vegetated parks are now more likely to be seen as integral components of both the ecology and the economy of postindustrial cities. Parks will also continue to serve as places of solace, places of congregation, places of relief from traumatic events, places for awe,places for seduction, places for escape, places for play, places where people can sit and think, places that—in Geoffrey Jellicoe’s words—“lift people out of their everyday lives”. They will continue to be integral parts of cities and habitats for humans and for other species.

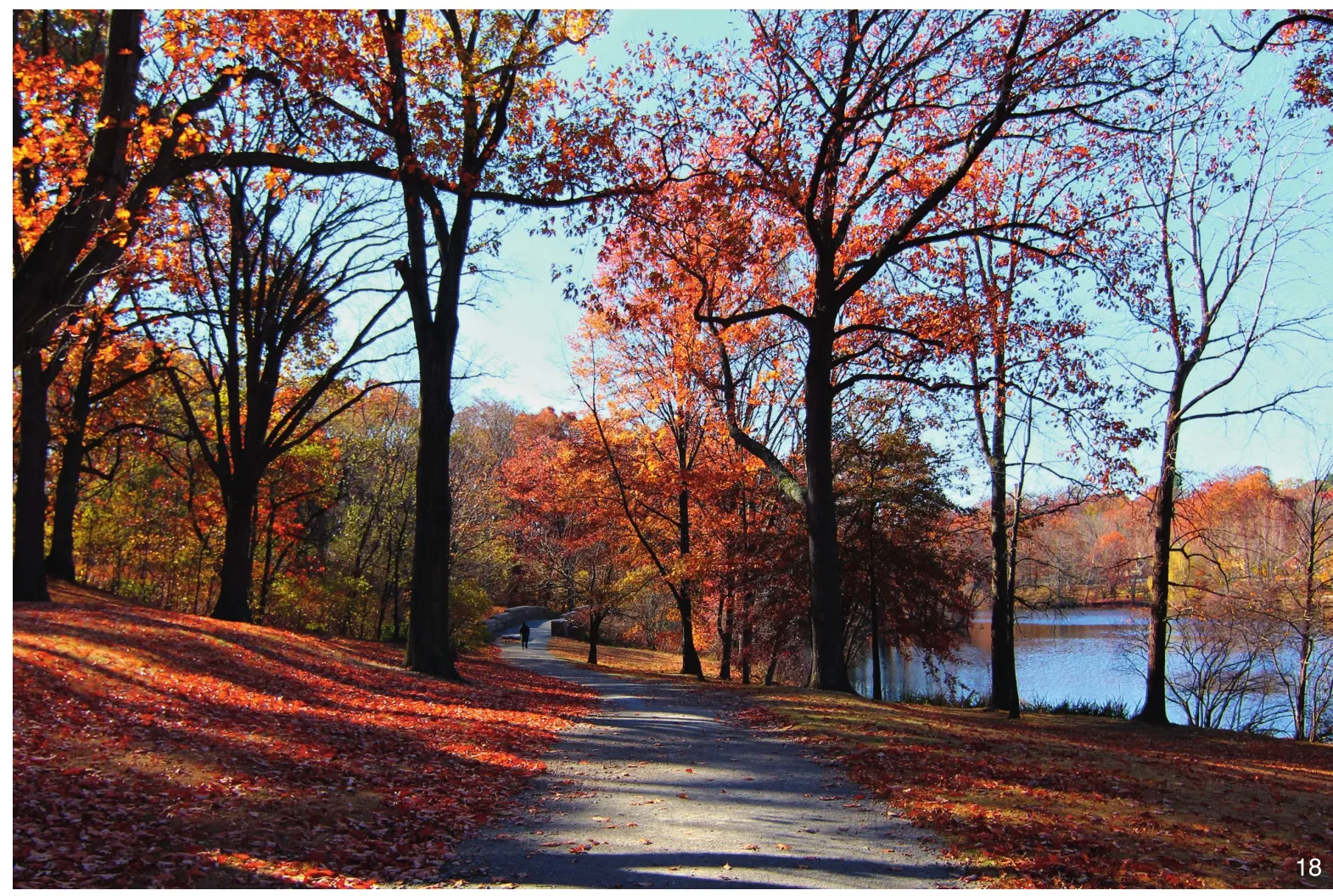

18 奥姆斯特德公园的步行道(翡翠项链,波士顿)Footpath through Olmsted Park (The Emerald Necklace, Boston)

This leads to an argument that city parks are one of the most important components of urban landscape infrastructure. That argument is based on the premise that landscape architects have always looked for landscape linkages—for connection and continuity in urban landscapes. And the argument can be extended to suggest that, in future,landscape architects will have to look for more unlikely linkages in increasingly densely developed cities. The argument begins with the two early London parks—Regent’s Park (from 1811) and St James’s Park (redesigned in 1827)—linked via Portland Place and Regent Street, providing an early example of landscape as infrastructure.Shortly thereafter, in 1829, following a threat of development on the hilly Hampstead Heath to the north of London, John Claudius Loudon(1783—1843) proposed concentric rings of“Breathing Spaces for the Metropolis” right around the city. Loudon’s proposal ref l ects the emerging idea of parks as the “lungs of the city”. This was early recognition of the role of urban landscape as part of the physical and mental health infrastructure of cities.

And pursuing the anatomical analogy, it is worth noting that the objectives for the Parc de la Villette design competition described that park as“not so much a lung as a heart”[16]that would reanimate that part of the city—performing as the organ that inspires and regulates everything else. A similar story underpinned the planning and design of Paris under Napoleon III and Haussmann.First they converted two large royal hunting parks on the edge of Paris—the Bois de Vincennes (to the east) and the Bois de Boulogne (to the west)for public use. Then they developed the pattern of health-bringing (and easily policed) boulevards creating a network of parks and vegetated spaces—all designed to improve all sorts of “circulation” …of traff i c, air and human respiration.

Those parks included the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont (1864) with its technology-derived French curves. The Chaumont in its name means bald hill—a reflection of its previous life as a gypsum quarry, a knacker’s yard (for slaughtering old horses), a garbage tip and even a gallows where public executions took place. Now, along with the nearby Parc de la Villette, it is the “heart” of the district … f l ooded with people who can enjoy both the prospect of the city and an escape from it. And in time it may be linked to other parks in Paris—like the Parc André-Citröen away to the southwest of the city—via the Petite Ceinture, a piece of potential green infrastructure comparable to the 35-kilometre Beltline being developed around Atlanta in the United States.

19 纽威米尔湖到公园北部的景色(阿姆斯特丹森林公园)View towards the Nieuwe Meer to the north of the park (Amsterdamse Bos)

20 沿着小岛湖岸边的步行道(明尼阿波利斯公园系统)Footpath along the shore of Lake of the Isles (Minneapolis Park System)

We can see a similar pattern in the introduction of urban parks to North America—starting with Central Park, built on rocky ground, away from the then highly-valued Manhattan shoreline … and now providing some of the most expensive views in the world. Vaux and Olmsted’s Greensward plan (1857—1858) was based on the pastoral model of woodland,water and meadow first seen at Birkenhead Park(1845), adapted for the rocky site of Central Park.This model was perfected at Prospect Park (1866)with its protective bund around the periphery.

And after Prospect Park, Olmsted and Vaux developed their commitment to connection—like their proposed Parkways from Prospect Park down to the Brooklyn shoreline—which remain as boulevards through that part of New York. This commitment culminated for Olmsted in the nine parks that comprise Boston and Brookline’s Emerald Necklace (1878—1895).The Necklace largely follows a natural drainage corridor, demonstrating the importance of identifying and protecting natural assets in urban areas. Olmsted and his then colleague H. W. S.Cleveland contributed to the development of the park system in Chicago following the “Great Fire” of 1871, with its celebrated Lakeshore Drive and its less celebrated chain of parks and boulevards. Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett’s subsequent Plan of Chicago (1909) was the high point of the City Beautiful Movement in the United States. Grant Park sat at its centre with the Beaux-Arts Buckingham Fountain on the axis of the re-designed city—a clear example of green infrastructure as a focus of the restructured city.

As mentioned, Cleveland moved from Chicago to plan the Minneapolis park system—applying lessons from Haussmann’s Paris and from post-fire Chicago to create one of the finest examples anywhere of linked landscape infrastructure before development could reach it,privatise it, and preclude public access to it. To this day, only one of the many lakes—Cedar Lake—has a private shoreline. And, as in so many cities in the United States—particularly inner cities—landscape infrastructure has been re-connected across downtown freeways … like the bridge over the Interstate-94—connecting the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden to Loring Park, effectively the Central Park of Minneapolis. Another example of parks contributing to interconnected landscape infrastructure is the Seawall around the 405 hectare “trapped wilderness” of Stanley Park in Vancouver, Canada—a city that aspires by 2020 to be the “Greenest City in the World”. The signif i cant point here is that the Seawall ties into the city-wide system of greenways proposed by planner Harland Bartholomew in 1926.Although these ideas take time to materialise,opportunities have to be recognised and acted upon as early as possible.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, the Amsterdamse Bos—a 1930s make-work project (also with signif i cant areas of forest, water and meadow)—is still expanding southward through the Schinkelbos,and northward to absorb the Nieuwe Meer after incursions like the Sport Park and Tennis Centre on the Amstelveen side of the forest. Continuing this chronological overview of connections, the County of London Plan from 1943 by Abercrombie and Foreshaw demonstrated the principles of landscape as infrastructure—but an era of rapid suburbanization, shrinking city populations and park decline followed World War II in most of Europe and North America. There has been some reversal of central city shrinkage since 2000 but Europeans and North Americans still live in an era of relatively low density urban expansion[17].

The emergence of new parks after World War II was slow, and in a case like Paley Park in New York, slow and private. But the fightback continued with projects like Halprin’s pioneering Freeway Park, built over the Interstate-5 in downtown Seattle. The 2017 ASLA National Award-winning Klyde Warren Park in downtown Dallas, built across the Woodall Rodgers Freeway is a more recent and more dramatic example of this fightback—a prime example of landscape infrastructure linking a previously dissected community. This commitment to connection is evident at all scales—such as the bridge between the two sections of Parc de Bercy in Paris or at the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park which includes numerous bridges within the park and connections southward to the River Thames—to complete the link with the 42-kilometre-long Lee Valley Regional Park (proposed by Abercrombie and Forshaw in that County of London Plan from 1943).

Conclusion

AlthoughGreat City Parksexamined a series of high-cost, high-profile projects like Bryant Park, New York; the Village of Yorkville Park in Toronto; Millennium Park in Chicago’s Grant Park; Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord, and the Westergasfabriek in Amsterdam, they were all extremely difficult sites either with toxic soils or on top of structures. And, as in the case of the Westergasfabriek, they still seek, first, to solve intrinsic (or inherited) site problems—to respond to their circumstances and context, and then to reach out and connect with their wider settings.

And even the high-cost, high-profile, highmaintenance, High Line seeks to reach out and provide visual links to its past and to the city of which it remains such an integral part. As Corner has noted, the High Line is an outstanding example of looking to make the most out of the least.This will be particularly important in China with anticipated urbanisation over the next 15 years including some 230 million new urban dwellers①.

The High Line is so popular that numbers have to be restricted at peak times. And, as mentioned, charges are now made for nonresidents to visit the historic part of Park Güell.This apparently ubiquitous pattern of a huge rising demand for parks—both from residents and from tourists—was probably the most striking development that occurred between the 2001 and 2015 editions ofGreat City Parks.This influenced the choice of cover for the 2015 edition, showing Bryant Park, where the number of visitors is counted every lunchtime—including the proportion of women, on the principle that a higher proportion of women visitors indicates a safer park. In short, the argument that Hirschfeld made more than 200 years ago in hisTheorie der Gartenkunstabout the demand for parks remains valid in Europe, in North America … and in China.