巴尔扎克与“恶魔精神”

By Harold Bloom

Baudelaire2 observed, famously, that “every one of Balzacs characters, even the janitors, has some sort of genius.” Balzac, rather like Victor Hugo, outrageously was possessed by a genius, a daemonic will that drove him through the ninety novels and novellas that constitute The Human Comedy, deliberate rival to Dantes Divine Comedy.3 Reading the admirable Graham Robbs4 Balzac: A Biography, one comes away with the startled impression that Balzac cannot always be distinguished from his daemon. Since genius is my sole subject in this book,5 I will feel free to mix observations on Balzac himself with my account of his extraordinary character-of-characters, the master criminal Vautrin, also known as Jacques Collin and as the Abbé Carlos Herrera. Vautrin is crucial in Père Goriot (1834—35), Lost Illusions (1937—43), dominant in A Harlot High and Low (1838—47), and was the herovillain of the playVautrin (1840), banned after one performance by the Ministry of the Interior, to no great aesthetic loss.

Henry James, a superb literary critic except when he felt himself menaced (as by Hawthorne, Dickens, George Eliot), was at his best on Balzac, who for James possessed “a kind of inscrutable perfection.”6 This appeared to James the prime lesson that Balzac taught other novelists:

The lesson of Balzac, under this comparison, is extremely various, and I should prepare myself much too large a task were I to attempt a list of the separate truths he brings home7. I have to choose among them, and I choose the most important; the three or four that more or less include the others. In reading him over, in opening him almost anywhere today, what immediately strikes us is the part assigned by him, in any picture, to the conditions of the creatures with whom he is concerned. Contrasted with him other prose painters of life scarce seem to see the conditions at all. He clearly held pretended portrayal as nothing, as less than nothing, as a most vain thing, unless it should be, in spirit and intention, the art of complete representation.“Complete” is of course a great word, and there is no art at all, we are often reminded, that is not on too many sides an abject8 compromise. The element of compromise is always there; it is of the essence; we live with it, and it may serve to keep us humble. The formula of the whole matter is sufficiently expressed perhaps in a reply I found myself once making to an inspired but discouraged friend, a fellow-craftsman who had declared in his despair that there was no use trying, that it was a form, the novel, absolutely too difficult. “Too difficult indeed; yet there is one way to master it-which is to pretend consistently that it isnt.” We are all of us, all the while, pretending-as consistently as we can-that it isnt, and Balzacs great glory is that he pretended hardest. He never had to pretend so hard as when he addressed himself to that evocation of the medium, that distillation of the natural and social air, of which I speak, the things that most require on the part of the painter preliminary possession-so definitely require it that, terrified at the requisition when conscious of it, many a painter prefers to beg the whole question.9 He was thus, this ingenious person, to invent some other way of making his characters interesting-some other way, that is, than the arduous way, demanding so much consideration, of presenting them to us. They are interesting, in fact, as subjects of fate, the figures round whom a situation closes, in proportion as, sharing their existence, we feel where fate comes in and just how it gets at them. In the void they are not interesting-and Balzac, like Nature herself, abhorred a vacuum. Their situation takes hold of us because it is theirs, not because it is somebodys, any ones, that of creatures unidentified. Therefore it is not superfluous that their identity shall first be established for us, and their adventures, in that measure, have a relation to it, and therewith an appreciability.10 There is no such thing in the world as an adventure pure and simple; there is only mine and yours, and his and hers-it being the greatest adventure of all, I verily11 think, just to be you or I, just to be he or she. To Balzacs imagination that was indeed in itself an immense adventure-and nothing appealed to him more than to show how we all are, and how we are placed and built-in for being so. What befalls us is but another name for the way our circumstances press upon us-so that an account of what befalls us is an account of our circumstances.

The lesson of Balzac, under this comparison, is extremely various, and I should prepare myself much too large a task were I to attempt a list of the separate truths he brings home7. I have to choose among them, and I choose the most important; the three or four that more or less include the others. In reading him over, in opening him almost anywhere today, what immediately strikes us is the part assigned by him, in any picture, to the conditions of the creatures with whom he is concerned. Contrasted with him other prose painters of life scarce seem to see the conditions at all. He clearly held pretended portrayal as nothing, as less than nothing, as a most vain thing, unless it should be, in spirit and intention, the art of complete representation.“Complete” is of course a great word, and there is no art at all, we are often reminded, that is not on too many sides an abject8 compromise. The element of compromise is always there; it is of the essence; we live with it, and it may serve to keep us humble. The formula of the whole matter is sufficiently expressed perhaps in a reply I found myself once making to an inspired but discouraged friend, a fellow-craftsman who had declared in his despair that there was no use trying, that it was a form, the novel, absolutely too difficult. “Too difficult indeed; yet there is one way to master it-which is to pretend consistently that it isnt.” We are all of us, all the while, pretending-as consistently as we can-that it isnt, and Balzacs great glory is that he pretended hardest. He never had to pretend so hard as when he addressed himself to that evocation of the medium, that distillation of the natural and social air, of which I speak, the things that most require on the part of the painter preliminary possession-so definitely require it that, terrified at the requisition when conscious of it, many a painter prefers to beg the whole question.9 He was thus, this ingenious person, to invent some other way of making his characters interesting-some other way, that is, than the arduous way, demanding so much consideration, of presenting them to us. They are interesting, in fact, as subjects of fate, the figures round whom a situation closes, in proportion as, sharing their existence, we feel where fate comes in and just how it gets at them. In the void they are not interesting-and Balzac, like Nature

An exquisite account of Balzacs other characters, does this work for the master criminal Vautrin, Balzacs alter ego,12 perhaps his daemon? Rastignac, Lucien de Rubempré, Cousin Pons, Old Goriot, Eugénie Grandet, Baron Hulot,13 and all the other grand protagonists are indebted to Balzac for his showing how they are, and how they are placed. Vautrin is larger, as Balzac himself is, Graham Robb writes, “Balzac is both the embodiment of his age and its most revealing exception.” I transpose14 that to: Vautrin is both the embodiment of The Human Comedy and its most revealing exception. The outcast Vautrin, Satan of the criminal life of Paris, ends as head of the S?reté15. Balzac, the hack writer from Tours, received the final tribute at his funeral from the inevitable Victor Hugo, his only literary rival in sublime madness and unbelievable fecundity.16

Like Dickens, Balzac worked himself to death, though not as a public performer of his own works. Always apocalyptically17 in debt, he wrote in a frenzy, sometimes sleeping just two hours a night while drowning himself in coffee. Subject to hallucinations both auditory and visual, Balzac received in himself the ancient association of genius with madness. Though as grand a monomaniac as Victor Hugo, and as much a force of nature and an occult energy, Balzac was wholly a novelist, and therefore seems saner than Hugo, who wrote enormous novels, yet who was the poet proper,18 the poet of his language, however unfashionable in our tasteless era.

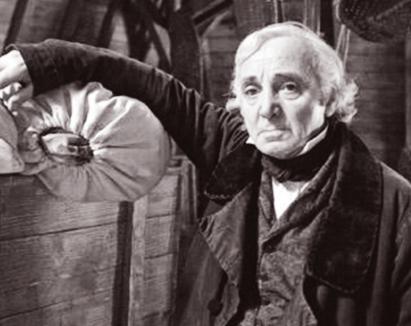

When we first encounter Vautrin in Père Goriot, we are not precisely aware of what titanism he conceals, but we are told this tough forty-year-old has “appalling depths within.”19 Vautrins literary lineage is more High Romantic than gothic:he is Byronic hero-villain, but a survivor.20 No one in Byron ever reaches forty, and one of Vautrins nicknames in the criminal cosmos is “Death-Dodger21.” Vautrin is not a quester22, and he is at war with a society he despises, but then he would be subversive of any nation, anywhere, anytime. He is pragmatically an anarchist, but this is pure paradox, since he has totally organized and imperiously rules over the entire criminal world.23 Since he is Parisian, not Sicilian24, his Satanic pride is individual rather than familial. His drive is homoerotic, but it remains ambiguous whether his desire for handsome young disciples is primarily sexual or a displaced paternalism,25 as Balzacs perhaps was. Vautrin is free of sexual jealousy, so long as his young men fell in love and form liaisons only with women.

Vautrins criminal genius is dramaturgical26: he wants to mold Balzacs characters, Rastignac and the poet Lucien, into something grander, and he is a superb scene-setter. Trapped in a police ambush, in part 3 of Père Goriot, he dodges death by an extraordinary art of command over his own fury:

“In the Name of the law, and the name of the king,”announced one of the officers, though there was such a loud murmur of astonishment that no one could hear him.

But silence quickly descended once again, as the lodgers moved aside, making room for three of the men, who came forward, their hands in their pockets, and loaded pistols in their hands. Two uniformed policemen stepped into the doorway theyd left and two others appeared in the other doorway, near the stairs. Soldersfootsteps, and the readying of their rifles, echoes from the pavement outside, in front of the house. Death-Dodger had no hope of escape; everyone stared at him irresistibly drawn. Vidocq went directly to where he stood, and swiftly punched Collin in the head with such force that his wig flew off, revealing the stark horror of his skull. Brick-red, short-clipped hair gave him a look at once sly and powerful, and both head and face, blending perfectly, now, with his brutish chest, glowed with the fierce, burning light of a hellish mind. It was suddenly obvious to them all just who Vautrin was, what hed done, what hed been doing, what he would go on to do; they suddenly understood at a glance his implacable ideas, his religion of self-indulgence, exactly the sort of royal sensibility which tinted all his thoughts with cynicism, as well as all his actions, and supported both by the strength of an organization prepared for anything. The blood rose into his face, his eyes gleamed like some savage cats. He seemed to explode into a gesture of such wild energy, and he roared with such ferocity that, one and all, the lodgers cried out in terror. His fierce, feral movement, and the general clamor hed created, made the policemen draw their weapons. But seeing the gleam of cocked pistols, Collin immediately understood his peril, and instantly proved himself possessor of the highest of all human powers. It was a terrible, majestic spectacle! His face could only be compared to some steaming apparatus27, full of billowing smoke capable of moving mountains, but dissolved in the twinkling of an eye by a single drop of cold water. The drop that doused28 his rage flickered as rapidly as a flash of light. Then he slowly smiled, and turned to look down at his wig. “This isnt one of your polite days, it is, old boy?” he said to Vidocq. And then he held out his hands to the policemen, beckoning them with a movement of his head.“Gentlemen, officers, Im ready for your handcuffs or your chains, as you please. I ask those present to take due note of the fact that I offer no resistance.

(translated by Burton Raffel)

“The highest of all human powers” here is the art of the great dramatist, Shakespeare or Molière, in representing sudden change in great characters, an Iago or a Tartuffe,29 or a Vautrin. Balzacs apotheosis in this art comes with “The Last Incarnation of Vautrin,”30 the final section of A Harlot High and Low. Vautrin, bereft of Lucien through the poets suicide, is transformed, phase after phase, from the Satan of the underworld to the God of the Parisian police establishment. Balzac dazzles the reader throughout the shock of this transformation, but he leaves me very uncertain what has happened to Vautrins Rousseau31 -inspired lifelong battle against society. Vautrin goes over to Balzacs side, thus becoming a legitimist, a royalist, and a prime preserver of the oligarchy.32 Though Vautrin has been all but33 traumatized by Luciens suicide, his conversation to the established order does not seem a reaction to this loss. Perhaps the explanation is the Balzacian energetic of power. Vautrin is now older, and even his diabolic energy may be on the verge of waning, while presumably the power of enforcement requires less strain than the power of subversion. Or again, perhaps the act of usurpation is the supreme accolade for Vautrin, Balzacs prime surrogate.34

One of Balzacs great inventions is the intricate dance of recruitment that is performed by Granville, the dignified and honorable attorney-general, and the endlessly metamorphic35 Vautrin, who in a sense is seduced by Granvilles authentic moral grandeur. The greatness of Vautrin recognizes, and is raised to a state of exaltation by, the rival greatness of Granville. As a reader, I sorrow at losing Vautrin to the state; it is rather as though Satan repented fully in Paradise Lost36, and rejoined the angelic orders. But Balzac was guiding his genius to safe harbor; he lived only three years beyond Vautrins metamorphosis from Death-Dodger to societys ultimate weapon against disorder. He needed Vautrin to be an allegory of his own posthumous destiny: to become a guardian of the human comedy he had so exuberantly imagined.37

波德萊尔有一句著名的评论:“巴尔扎克笔下的每一个人物,哪怕是门房,都具备某种天才。”巴尔扎克很像维克多·雨果,不可思议地受到天赋异禀的支配,那是一种恶魔附体般的意志力,驱使他接连创作出总称为《人间喜剧》的90部中、长篇小说,刻意与但丁的《神曲》(《神圣喜剧》)媲美。格雷厄姆·罗布那本精彩的《巴尔扎克传》给读者留下了骇人的印象:巴尔扎克常常与他的“恶魔精神”浑融一体,无分彼此。鉴于“天才”是拙著唯一的主题,我将在评论巴尔扎克本人的同时,自由穿插对于伏脱冷的分析。这位又名雅克·柯兰或者卡洛斯·埃雷拉神甫的犯罪大师是巴尔扎克人物塑造的神来之笔。伏脱冷是《高老头》(1834—35)和《幻灭》(1837—43)的关键人物,《交际花盛衰记》(1838—47)的头号主角,还是戏剧《伏脱冷》(1840)里的“英雄恶棍”(这个戏才上演了一次就被内政部给禁掉了,不过这在艺术上也算不得多大的损失)。

亨利·詹姆斯是一流的文学批评家,除非是感到自己的文学成就受到了威胁(比如来自霍桑、狄更斯和乔治·艾略特的威胁),他批评其他作家都很精当,论巴尔扎克则至为精彩。詹姆斯认为,巴尔扎克拥有“一种神秘莫测的完美”。对于詹姆斯来说,这是巴尔扎克教给其他小说家的最重要的创作经验:

相形之下,巴尔扎克的创作经验包罗万象,他所昭示的真谛举不胜举。笔者只能择其要者而论,好在我选择的三点或四点也多多少少涵盖了其他方面。在今天,细读巴尔扎克,随便翻开他作品里的几乎每一頁,一下子就打动我们的,是他展现的每一幅画卷都特别讲究将他所关注的人物放置在特定环境当中。和他相比,其他描绘生活场景的小说家对特定环境的观察还很不到家。巴尔扎克旗帜鲜明地提出,虚有其表的描绘,倘若究其旨趣不是为了创造出“完满表现的艺术”,就只能是空言、败笔和矫饰。“完满”当然是一种崇高的境界。经常有人提醒我们,没有哪件艺术品不是在万不得已的情况下多方妥协的产物。妥协的成分从来都存在;这就是创作的本质;我们无可奈何地忍受这个,由此常怀谦卑之心。关于此规律,我曾经在给一位朋友的回信中予以充分表述。他也是作家,富于灵感却倍感挫折,曾绝望地声称:再怎么尝试也不管用,长篇小说这种体裁确实是太难了。“说实在的,太难了;要掌握它只有一个办法——就是始终自欺欺人:写这个并不难。”我们每一个作家在创作的每一刻都在竭力假装写长篇小说并不难,而巴尔扎克之所以伟大,正是因为他假装得最卖力。当他致力于以文字的魔咒召唤人物的生活环境,对自然状况和社会风习进行艺术提炼的时候,他这种假装委实是卖力到了无以复加的程度。要做到我所说的召唤环境、提炼风习,描绘生活场景的作家必须从一开始就着魔似地不遗余力。真正做到这一点谈何容易,许多描绘生活场景的作家都知难而退,故意回避了整个问题的关键所在。巴尔扎克却灵思巧构,独辟蹊径,塑造出众多引人入胜的人物形象——所谓独辟蹊径,就是不凭死力气,不求面面俱到,也能将人物鲜活地呈现给读者。事实上,巴尔扎克的人物之所以引人入胜,是因为他们受命运拨弄。随着某种情势向这些人物步步逼近,我们能够感同身受地认识到命运在何处介入以及如何支配他们。离开了特定环境,这些人物就变得索然寡味——犹如大自然本身,巴尔扎克厌恶真空。人物所处的情势牢牢吸引了我们,不是因为这种情势属于随便某个人,属于所有人,或者属于身份暧昧不明的人,而是因为每个人自有其特殊的情势,绝不雷同。故此,人物甫一出场就要交代清楚身份的写法并非赘笔,他们的探险奇遇无不与之密切相关,不预作交代就要影响读者的理解。这个世界不存在简单划一的奇遇,只有你我他她各不相同的奇遇。我坚信,任何一种奇遇,只要是充分个性化的,就是最了不起的。巴尔扎克的想象力本身,就是一场规模宏大的探险奇遇。他最大的乐趣,就是展现众生百态,还有人物所置身和嵌入的环境对此起到的决定作用。个人遭际无非是环境如何压迫个人的代名词,故此,描写个人遭际也就是描写特定环境。

以上论述能够精妙地诠释巴尔扎克笔下的其他人物,可是用于解读犯罪大师伏脱冷依然奏效吗?伏脱冷是巴尔扎克的第二自我,或许就是他的恶魔精神的化身。通过展现众生百态,揭示他们如何受环境摆布,巴尔扎克塑造出拉斯蒂涅、吕西安·德·吕邦泼雷、邦斯舅舅、高老头、欧也妮·葛朗台、于勒男爵等一系列栩栩如生的主要人物。但伏脱冷比他们都要伟大,正如巴尔扎克本人比其同辈小说家都要伟大。格雷厄姆·罗布写道:“巴尔扎克既是时代精神的化身,又是其最发人深省的例外。”我将这句话改为:“伏脱冷既是《人间喜剧》的化身,又是其最发人深省的例外。”伏脱冷是社会体制的弃民、巴黎黑社会的撒旦,最后却当上了巴黎秘密警察的头目。巴尔扎克来自图尔城,以卖文为生,维克多·雨果却一定要在他的葬礼上敬献悼词的礼赞。论起对诗性崇高的痴狂和令人难以置信的多产,也只有雨果足以和他媲美。

巴尔扎克和狄更斯一样,一直写作到生命的最后一息,不过他不曾像狄更斯那样时常在公众面前朗诵表演自己的作品。巴尔扎克总是负债累累,担忧末日将至,不得不疯狂写稿,有时一晚上只睡两个小时,靠拼命喝咖啡硬撑着。他经常处于一种听觉和视觉的迷幻状态当中,令人联想到那句老话:天才距离疯子仅一步之遥。巴尔扎克和雨果一样,都是不可一世的偏执狂,都具备自然的伟力和神秘主义的创作能量。不过,巴尔扎克是纯粹的小说家,所以看似比雨果要理智一些(雨果写过几部长篇小说巨著,但严格说来,他原本是诗人,法语世界里最伟大的诗人,虽说这么描述他在我们这个缺乏品位的时代显得非常不合时宜)。

当我们在《高老头》里初次遭遇伏脱冷的时候,并没有很准确地意识到在他韬光隐迹的外表下隐藏着怎样的泰坦精神,可是小说告诉我们,这个40岁的狠角色“不时流露的性格颇有些可怕的深度”。如果追溯伏脱冷的文学谱系,浪漫主义高峰期的色彩要胜过哥特体小说的色彩:他是拜伦式的英雄恶棍,只不过屡次死里逃生。在拜伦笔下没有任何一个人物可以活到40岁,而伏脱冷在黑道上的诨名之一就是“鬼上当”。伏脱冷不是探险立功的骑士,他在和一个他所蔑视的社会作战,但另一方面,无论何时、何地、对于哪个国家政权,他都是颠覆性力量。在实践上他是一个无政府主义者,可是这当中充满了自相矛盾,因为他一手缔造了整个黑社会并实行独裁统治。由于他是巴黎人,而不是西西里人,他那种撒旦式的桀骜不驯与其说是来自家族的影响,不如说是个性使然。他喜欢年轻貌美的男弟子,表现出同性恋的本能欲望,可是这种欲望究竟是基于性欲呢,还是一种父爱的移情,小说对此交代得很暧昧。巴尔扎克本人的性倾向或许也是如此。伏脱冷从不争风吃醋,只要他的小伙子们爱上并与之发生浪漫关系的是女人。

伏脱冷的犯罪天才是契合戏剧表现艺术的:他想要把巴尔扎克笔下的人物拉斯蒂涅和诗人吕西安改造成上流社会精英,又出色地搭建了舞台。在《高老头》第三章里,伏脱冷中了警察的埋伏,他抑制住了自身的狂怒,凭此非凡技艺死里逃生:

“兹以法律与国王陛下之名……”一个警务人员这么念着,以下的话被众人一片惊讶的声音盖住了。

不久,饭厅内寂静无声,房客闪开身子,让三个人走进屋内。他们的手都插在衣袋里,抓着上好子弹的手枪。跟在后面的两个宪兵把守客厅的门;另外两个在通往楼梯道的门口出现。好几个士兵的脚步声和枪柄声在前面石子道上响起来。鬼上当完全没有逃走的希望了,所有的目光都不由自主地盯着他一个人。特务长笔直地走过去,对准他的脑袋用力打了一巴掌,把假头发打落了。柯兰丑恶的面貌马上显了出来。土红色的短头发表示他的强悍和狡猾,配着跟上半身气息一贯的脑袋和脸庞,意义非常清楚,仿佛被地狱的火焰照亮了。整个的伏脱冷,他的过去,现在,将来,倔强的主张,享乐的人生观,以及玩世不恭的思想,行动,和一切都能担当的体格给他的气魄,大家全明白了。全身的血涌上他的脸,眼睛像野猫一般发亮。他使出旷野一般的力抖擞一下,大吼一声,把所有的房客吓得大叫。一看这个狮子般的动作,暗探们借着众人叫喊的威势,一齐掏出手枪。柯兰一见枪上亮晶晶的火门,知道处境危险,便突然一变,表现出人类的最高的精神力量。那种场面真是又丑恶又庄严!他脸上的表情只有一个譬喻可以形容,仿佛一口锅炉贮满了足以翻江倒海的水汽,一眨眼之间被一滴冷水化得无影无踪。消灭他一腔怒火的那滴冷水,不过是一个快得像闪电般的念头。他微微一笑,瞧着自己的假发,对特务长说:

“老伙计,你今天不客气啊!”

他向那些宪兵点点头,把两只手伸了出来。

“来吧,宪兵,拿手铐来吧。请在场的人作证,我没有抵抗。”

(根据傅雷译《高老头》,略有改动)

在这里,“人类的最高的精神力量”指的是伟大的戏剧家如何表现伟大的人物突然转变的艺术,像莎士比亚笔下的伊阿古,莫里哀笔下的达尔杜弗,或者巴尔扎克笔下的伏脱冷。在《交际花盛衰记》的最后一部《伏脱冷最后的脱胎换骨》里,巴尔扎克对这种艺术的运用臻于化境。诗人吕西安的自杀使伏脱冷受到了巨大打击,他一步一步由黑社会的撒旦蜕变为巴黎保安警察的守护神。巴尔扎克笔下这一惊人的蜕变令读者为之目眩,却让我感到茫然:伏脱冷,那个受卢梭感召、毕生与主流社会作战的斗士,他身上究竟发生了什么事儿?伏脱冷皈依到了巴尔扎克的立场上,由是成为正统王朝派、保皇党、寡头政治的主要拥护者。尽管吕西安的自杀差不多给伏脱冷带来了难以平复的心理创伤,看来他并不是因为这个损失才归顺既有秩序。或许巴尔扎克式精力观能解释这一突变。伏脱冷已经不再年轻,他那恶魔般的精力正在逐渐衰竭,而维护社会所需的能量大概总是比颠覆社会所需的能量要少。也可能,篡夺主流社会的权力正是对于伏脱冷—— 巴尔扎克的主要替身—— 的最高奖赏。

巴尔扎克的天才创造力,在德高望重的总检察长格朗维尔招抚不断改头换面的伏脱冷这段高难度舞蹈里,得到了淋漓尽致的表现。在某种意义上,伏脫冷归顺官府,是为格朗维尔真正的道德崇高所感召。英雄慧眼识英雄,格朗维尔的杰出烘云托月般彰显出伏脱冷的杰出。作为读者,我深深惋惜伏脱冷杀人放火受招安的结局,就好像《失乐园》里的撒旦彻底忏悔,加入了天使的行列。不过,巴尔扎克将他笔下的天才人物带入安全的避难所。在伏脱冷从“鬼上当”蜕变为主流社会打击犯罪的杀手锏之后三年,巴尔扎克就与世长辞。他需要伏脱冷作为自己身后命运的象征:成为那倾注了他丰沛想象力的人间喜剧的守护人。

1. daemon(形容词为daemonic): 本指希腊神话中半人半神的精灵,后用于形容天才型艺术家,具备非凡的力量、精力和智慧。

2. Baudelaire: 波德莱尔(1821—1867),法国诗人、散文家和艺术批评家,诗集《恶之花》对后来的象征主义和现代主义产生巨大影响。

3. Victor Hugo: 维克多·雨果(1802—1885),法国浪漫主义运动的代表诗人、小说家和戏剧家;outrageously:骇人地;The Human Comedy :《人间喜剧》,巴尔扎克以毕生心血创作的,由九十多部独立而又有所联系的长篇小说和故事组成的作品总集;Dante: 但丁(约1265—1321),中世纪晚期意大利文艺复兴运动最伟大的诗人;Divine Comedy : 但丁创作的长诗,国内通译为《神曲》,而意大利语Divina Commedia 原义为《神圣喜剧》。

4. Graham Robb: 格雷厄姆·罗布(1958— ),研究法国文学和历史的英国作家,他为法国三大文豪巴尔扎克、雨果和兰波撰写的传记均受批评界好评。

5. 本文选译自哈罗德·布鲁姆的作家评论专著Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Creative Minds (2003),所以作者说“‘天才是拙著唯一的主题”。

6. Henry James: 亨利·詹姆斯(1843—1916),长期侨居欧洲的美国小说家和文学评论家,从现实主义文学向现代主义文学过渡的关键人物之一;menace: 威胁;Hawthorne: 霍桑(1804—1864),美国19世纪最伟大的浪漫主义小说家;Dickens(1812—1870), George Eliot(1819—1880): 狄更斯和乔治·艾略特,英国维多利亚时代的两位长篇小说巨匠;inscrutable: 不可思议的,难以捉摸的。

7. bring home...: 使……清晰易懂。

8. abject: 凄惨的,糟透的。

9. address oneself to...: 致力于……,专心从事……;evocation: 唤起;medium: 周围环境;distillation: 蒸馏,提炼;possession:鬼魂附体,着魔;requisition: require的名词形式;beg the question:(习语)避重就轻,回避问题的实质。

10. superfluous: 多余的;therewith: (古语, =with that/this/ it)于是;appreciability: 由appreciable(可以理解的,可以欣赏的)衍生的名词。

11. verily: (古语,=truly)确实。

12. exquisite: 精美的,优雅的;alter ego: 另一个自我,个性的另一面。

13. Rastignac, Lucien de Rubempré, Cousin Pons, Old Goriot, Eugénie Grandet, Baron Hulot: 拉斯蒂涅(《高老头》)、吕西安·德·吕邦泼雷(《幻灭》、《交际花盛衰记》)、邦斯舅舅(《邦斯舅舅》)、高老头(《高老头》)、欧也妮·葛朗台(《欧也妮·葛朗台》)、于勒男爵(《贝姨》),均为《人间喜剧》里的主要人物。

14. transpose: 使移位,(音乐)使变调。

15. S?reté:(法语)巴黎秘密警察。

16. hack writer: 受雇写粗制滥造文章的职业文人;Tours: 图尔,法国中西部城市;sublime:“诗性崇高”,布鲁姆文学批评的关键词之一;fecundity: 多产。

17. apocalyptically: 由名词apocalypse(世界末日)衍生的副词。

18. monomaniac: 偏执狂,狂热于一事的人;occult: 神秘学的,超自然的;proper:(用于名词后)真正的,严格意义上的。

19. titanism: 泰坦精神,(对社会习俗、权威等的)反叛精神(泰坦:希腊神话中的古老神族,曾统治世界,但被宙斯神族推翻并取代);appalling: 可怕的。

20. High Romantic:(文学)浪漫主义高峰期的;gothic:(小说)哥特体的(描写怪诞、神秘的恐怖故事,多发生在坟墓和古堡);Byron: 拜伦(1788—1824),英国浪漫主义文学的代表詩人。Byronic意为“拜伦式的”。

21. Death-Dodger: 躲过死神的人,dodge意为“躲开,避开”。

22. quester: 由quest(中世纪传奇里骑士的探险奇遇)衍生的名词。

23. anarchist: 无政府主义者;paradox: 悖论,自相矛盾的事物;imperiously:专横地。

24. Sicilian: 西西里为意大利黑手党发源地。

25. drive: 强烈欲望,本能需求;homoerotic:同性恋的;paternalism: 父亲般的关怀。

26. dramaturgical: 由dramaturgy(剧作法,戏剧表现艺术)衍生的形容词。

27. apparatus: 仪器,装置。

28. douse: 浇灭(火)。

29. Iago: 伊阿古,英国戏剧家莎士比亚(1564—1616)悲剧《奥赛罗》里的主要反角;Tartuffe: 达尔杜弗,法国戏剧家莫里哀(1622—1673)同名喜剧(又名《伪君子》)里的主要反角。

30. apotheosis:(事业或人生的)顶峰;incarnation: 化身。

31. Rousseau: 卢梭(1712—1778),法国哲学家、启蒙思想家。

32. legitimist: 正统王朝拥护者; royalist:保皇党;oligarchy: 寡头政治。

33. all but:(=almost)几乎,差不多。

34. usurpation: 篡权;accolade: 嘉奖;surrogate: 替身。

35. metamorphic: 变形的,名词形式为metamorphosis。

36. Paradise Lost: 英国诗人弥尔顿(1608—1674)创作的史诗《失乐园》(1667),取材自《圣经·旧约·创世记》,讲述撒旦对上帝的不屈反叛和天国战争。

37. allegory: 象征,寓言;exuberantly: 丰富地,充沛地。